13 minute read

Bridge

Michael O’Loughlin has enjoyed teaching bridge for over 40 years; his book, “Bridge: Basic Card Play” is available from the Contract Bridge Association of Ireland (01 4929666), price:E10.

Introducing the Senior Times bridge column by Michael O’Loughlin

We are often asked, why is contract bridge so avidly enjoyed by so many people?’. This question is usually raised by someone who has never learned the game, but whose interest has been piqued by friends or relatives who have been bitten by the ‘Bridge Bug.’

It is not surprising that the game is highly appealing, because it combines so many fascinating features. Some of which are:

Social A game of bridge involves communication and cooperation with your partner and interaction with your opponents. There’s a special camaraderie amongst bridge players that develops from the social setting and the game’s emphasis on teamwork, ethics and sportsmanship.

Skilful A player who has learned well will win more often than one whose technique is inadequate, for bridge is first and foremost a game of skill. It is sufficiently demanding to provide a challenge to all; it requires such abilities as reasoning, memory, and planning. Yet anyone who is willing to invest some time and effort can learn to play, and you need not be an expert to find enjoyment.

Chance On some occasions, you will be dealt powerful cards and will reap the benefits--if you can apply the necessary skill. On less fortunate occasions your opponents will be blessed by the goddess of chance and will hold considerable strength, and you will have to combine your skill with whatever good cards you do possess to try to turn defeat into victory. The interplay of skill and chance is one of the most appealing features of bridge.

The personal element Taking into consideration the behaviour patterns of your opponents is yet another intriguing aspect of bridge. For example, some opponents consistently overvalue their cards, and you can let them climb out on a limb and cut it off behind them; others tend to undervalue their cards and should be left strictly alone. Also, the care of partners is particularly important. In bridge, you have a partner to assist you in the battle against your two opponents, and partner’s habits must also be kept in mind. Thus, a close decision would be resolved differently opposite an aggressive partner (who often announces unpossessed strength) than with a conservative partner (who always turned up with something in reserve). A highly unusual action that might be justified with a clever partner could be extremely foolhardy with one less imaginative. Bridge involves “playing the people” as well as playing the cards.

Uniqueness In bridge, exact situations are virtually never duplicated. The reason for this is that there are no fewer than 635,013,559,600 possible hands, so you are most unlikely ever to see the same one recur twice in your lifetime, even if you play every day. Thus, every situation will offer something unique. Certain general principles, however, are useful in many different situations, and their mastery is rewarding to serious students of the game.

Fun Of all the reasons to learn the game, the most important is that it’s just fun to play.

A lifelong pursuit No matter how many years you play, the learning process will never end. Bridge also caters to all physical conditions and disabilities, so players can actively pursue their pastime throughout their entire lives.

Stimulates the brain One of the best ways to practise the ‘use it or lose it’ advice for maintaining mental sharpness in older age. Research has shown that regular bridge playing improves reasoning skills and long- and short-term memory. cards and three other people. You can play at your local club, where you’ll enjoy a threehour session of bridge for just a small outlay. Without even leaving home you can play on the internet.

Getting started: for absolute beginners

Bridge (short for Contract Bridge) is a trick-taking card game played by 2 pairs. Each pair forms a partnership and plays against the other pair. Each player sits at one side of a square table facing his/her partner:

NORTH

WEST EAST

SOUTH

To designate each of the four players it is convenient to use the four cardinal points of the compass: North, South, East and West. North and South play together as partners and their opponents are the partnership made up of East and West.

The partnerships may be pre-arranged or may be decided by drawing cards: the two players who pick the highest cards become partners. Similarly for deciding who is the dealer.

The pack of 52 cards may be dealt in advance (pre-dealt): each player taking his hand of 13 cards from a pocket or else the cards are dealt one at a time face down, clock-wise, starting on dealer’s left. If the cards are dealt at the table, then, the player on dealer’s left shuffles and the player on dealer’s right cuts. Easy way to remember: knife and fork: knife on right cuts. Dealer completes the cut and deals one card at a time starting on their left.

Both partnerships are trying to win tricks for their side. How are tricks won? Let’s suppose each of the 4 players, in turn, plays a Diamond. Then, whoever plays the highest Diamond wins that trick. The cards are ranked – from the highest to the lowest – as follows: Ace – King – Queen – Jack – 10 – 9 – 8 – 7 – 6 – 5 – 4 – 3 – 2.

For example, if West plays the ◆ 2, North the ◆ 9, East the ◆ K and South the ◆ A, then South wins that trick. One player commits his side/partnership to winning a certain number of tricks.

For novice-intermediates

Opening 1NT

Some open 1NT with a Balanced Hand and 12 -14 points; others open 1NT with a Balanced Hand and 15 – 17 points. What matters is that you have partnership agreement and that you inform your opponents.

However points aren’t everything. Bridge is about winning tricks. Points are but a guide to trick-taking, not a gospel. Let’s assume you have agreed with your partner to open 1NT with a Balanced Hand and 12 – 14 points. Now consider these three hands:

Hand a) Hand b)

♠ Q 10 8 ♠ J 5 3 ♥ K J 10 ♥ A J 2 ♦ A J 10 9 5 ♦ K J 2 ♣ 10 9 ♣ Q 7 3 2 Hand c)

♠ A Q 2 ♥ K J 2 ♦ A J 2 ♣ 7 5 3 2

• Hand (a) is superb – a good five-card suit in a hand replete with intermediates, i.e., tens and nines. This hand is clearly worth at least 12 points. You should open 1NT.

• Hand (b) on the other hand is really grotty – no intermediates, no sequential high cards, and

Bill Gates and Warren Buffett playing bridge.

the barren 4333 shape. This hand is not worth 12 points and you should not open 1NT, rather pass.

• Hand (c) is a very poor 15 for the same reasons as (b) is a poor 12 – barren shape, no intermediates, no sequences. Your hand is worth only 12-14 points and you should downgrade and open 1NT.

If someone says, ‘You can’t open 1NT with (say) Hand (c) because you’ve got 15 points’ (as though you’re in some way cheating), reply that you are allowed open anything you like and that you have used your judgement.

How declarer plays a no trump contract

Many people are frightened of playing in NT – without the security blanket of a trump suit. Whilst it is true that NT contracts can fall apart (typically, if the opponents can run a long suit), they are generally easier to play than suit con Senior Times, in association with Michael O’Loughlin and the Contract Bridge Association of Ireland are offering three copies of Bridge: Basic Card Play in this competition. To enter simply answer this question: there are a huge amount of possible hands in bridge. What is the first number of the total? Send your answer to: Senior Times, C/O Box Number 13215, Rathmines, Dublin 6, Ireland. Or email: john@slp.ie

tracts because there are fewer options available: issues such as ruffing and whether to draw trumps do not arise.

1. Try to analyse the Opening Lead. Usually it will be 4th highest – so you can use the Rule of 11: subtract the card led from 11 and this will give you the number of cards higher than the card led which are in the other 3 hands (the 3 hands apart from the person who led). For example, suppose West leads the 6; 11 – 6 = 5; therefore, there are 5 cards higher than the 6 between North’s, South’s and East’s hands. On occasion, this can help Declarer to place every significant card in the suit led:

AQ95

(West) KJ86 43 (East)

1072

Three copies of Michael O’Loughlin’s best-selling Bridge: Basic Card Play to be won!

Declarer the winners. Deadline for receipt of entries is 30th October 2020

Michael O’Loughlin has enjoyed teaching bridge for over 40 years; his book, Bridge: Basic Card Play is available from the Contract Bridge Association of Ireland (01 4929666), price: €10.

‘There are numerous books written on how to learn bridge. Many of them use plenty of words and say very little that would be clear to a beginner’s mind, whereas Michael O’Loughlin in his Bridge: Basic Card Play deals with the subject in a crystal-clear style’. George Ryan, The Irish Times, 2013

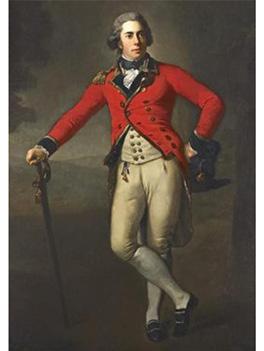

During the Good Old Days before Covid19 put a halt to our gallops I attended an exhibition of Nathaniel Hone’s paintings at our National Gallery. Nathaniel (1831-1917) was a scion of that Hone family that includes his great grand uncle, the painter, Nathaniel Hone the Elder (1718-1784), and the painter and stained-glass artist Evie Hone (18941955). Among the younger Nathaniel’s paintings on show, all of them very engaging, one in particular caught my attention: a landscape depicting the famous caryatid monument in Greece in which the six female figures (the ‘caryatids’) act as pillars to hold up the entablature overhead. The artist does a fine job in showing the monument in all its ruined beauty. It is indeed a wonderful artifact and makes a compelling subject for any artist, and especially one as accomplished as Hone in conjuring up the beauty of classical Greece. But it was the gallery note beside the picture that arrested my attention almost as much as the painting. It The Conjuror by Nathaniel Hone Hone the Elder (1718-84), depicts a figure resembling Sir Josuah Reynolds (17231792), the famous English portraitist, whom Nathaniel the Elder represents as pointing to prints resembling works by

The Nathaniel Hones, the Caryatids and the Elgin Marbles

Random thoughts on cultural vandalism by Eamonn Lynskey

Michelangelo and other famous artists. informed me that although Hone had painted six figures, only five were in situ by the time he arrived in Greece. One can only assume that, as an artist, his sensibilities would not allow him to break the symmetry of the classical design and so perhaps that was the reason why he performed this sleight of brush.

But what happened to the missing caryatid? Subsequent excursions on Wikipedia (long may its name be praised!) told me that she had ended up as an ornament in the garden of the Scottish Lord Elgin, having been ‘appropriated’ by him in 1801, the year that he had his men hack off half the frieze from the nearby Parthenon. He claimed he had received permission but that is seriously in doubt. Subsequently he sold the pieces to Great Britain and they were deposited in the British Museum where they have been on show ever since as ‘The Elgin Marbles’.

It is argued that Lord Elgin did us all a favour in removing these ancient artefacts, thereby saving them from the ravages of erosion. However Elgin’s dreadful act remains one of the most iconic examples of imperial rapaciousness

The Parthenon, Athens from where Lord Elgin ‘removed’ his celebrated marbles them from the ravages of erosion. Certainly it is true that they had suffered from the weathering of 2500 years. There is also the sad fact that some stonework from the Parthenon and the monument complex around it had been carted away as building material. The site was indeed in an increasingly perilous physical condition by 1801. However, since Greece has now the ways and means of overcoming these difficulties there should be no refusal to its request (made many times over the years) that these important cultural artefacts be returned to where they belong. Furthermore, the contention that Elgin was primarily concerned about the physical state of these architectural treasures wears thin when we consider that he attempted to remove a second caryatid and, when technical difficulties arose, tried to saw it in pieces. The statue was smashed in the process and its fragments scattered. It was later restored by the Greek authorities. Elgin’s dreadful act remains one of the most iconic examples of imperial rapaciousness, but is only one in a sad litany. I was stunned when I saw the great ornamental urns in Beijing’s Forbidden City still bearing the marks left by the British occupying forces after they had scraped off the gold coating. In fairness, I should add that the British were not alone in having engaged in ‘cultural vandalism’. Think of the depredations inflicted on the Inca temples by the Spanish. And as for the argument that The Elgin Marbles in situ in The British

Museum,London. But for how long? Caryatids by Nathaniel Hone the Younger (1831-1917). Photo © National Gallery of Ireland inclusions he managed to cast aspersions on ‘those times were different times, with different attitudes ’ – that ‘excuse’ does not lessen the horror.

But back to Nathaniel Hone. He was a member of a prominent Anglo-Irish family that arrived in Ireland with Cromwell and which over the centuries produced men and women gifted in several walks of life, including the production of fine artwork. But it was Nathaniel’s ancestor, Nathaniel Hone the Elder (1718-84), that came painting. I hurried down to the Irish Rooms to view again his large canvas, ‘The Conjuror’, which he painted in London in1775, during a period of intense rivalries in the art world (when was there ever a period without?).

‘The Conjuror’ depicts a figure resembling Sir Josuah Reynolds (1723-1792), the famous English portraitist, whom Nathaniel the Elder represents as pointing to prints resembling works by Michelangelo and other famous artists. It is a satirical picture and clearly implies that Reynolds was engaging in plagiarism, as its title suggests. It was a canvas that involved Hone the Elder in a good deal of controversy at the time, not least because by other careful

into my mind while I was viewing the caryatid other aspects of Reynolds’ character.

It is obvious that the elder Nathanial was more than miffed at such apparent ‘borrowings’ from the works of others and wanted to make a point about people who might be stealing other people’s work.

No doubt the younger Hone shared the strong disapproval of his ancestor in this matter, as would most artists. Perhaps he also may have felt instinctively that he should repair the damage done to the classical Greek monument by restoring the stolen caryatid, thereby rescuing something of its former splendour? An idle conjecture on my part I know, but one which I like to believe. It certainly presents a more pleasing picture than the thought of the Lord Elgin attempting to saw a second caryatid into sections for transport home to sell to the British Museum.