Happy 75th Anniversary SETC! This year’s Convention was fruitful and expansive as I witnessed networking, community, and collaboration throughout the week. What was most striking to me was that the organization is beginning, albeit slowly, to reflect the demographics of the US—a country representative of diverse peoples and cultures. This feat is in part due to the dynamic leadership of our Executive Director and SETC co-conspirators who share the same values of equity and inclusion. For this, SETC should be most proud.

As an attendee I also witnessed workshops, conversations, and keynotes that reflected on the current landscape of our evolving industry and how SETC goers might be generative participants.

As Toni Simmons Henson reminds us, “SETC is an incubator for talent and empowerment,” and I have no doubt that the hundreds of attendees took advantage of all SETC had to offer through the week. From overhearing phrases such as “That was so fun” to “Wow” to “I hope they offer that again next year,” it is clear that SETC is firmly rooted in the present while planting and watering seeds for the future. I’m thrilled that the Editorial Board and I can be a part of the magic in a way that documented much of what occurred.

In this issue, you’re able to read about all of the fabulous, distinguished keynotes from celebrities such as S. Epatha Merkerson and Beowulf Borritt. You’ll get to catch up on views of censorship from Howard Sherman who presented at the Teachers Institute, and you can read an excerpt from D.W. Gregory’s new play—while enjoying all of the wonderful photos captured at the Convention. Enjoy. SETC Strong!

Sharrell aka Dr. L Editor-in-Chief @sdluckett

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Sharrell D. Luckett, PhD

SETC PRESIDENT

Jeremy Kisling

SETC EXECUTIVE

DIRECTOR

Toni Simmons Henson

ADVERTISING

Thomas Pinckney, thomas@setc.org

BUSINESS & ADVERTISING OFFICE

Southeastern Theatre Conference

5710 W. Gate City Blvd., Suite K, Box 186 Greensboro, NC 27407 info@setc.org

PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE

Becky Becker, Clemson University (SC)

Ricky Ramón, Howard University (DC)

EDITORIAL BOARD

Tom Alsip, University of New Hampshire

Keith Arthur Bolden, Spelman College (GA)

Amy Cuomo, University of West Georgia

Caroline Jane Davis, Furman University (SC)

David Glenn, Samford University (AL)

Kyla Kazuschyk, Louisiana State University

Sarah McCarroll, Georgia Southern University

Tiffany Dupont Novak, Actors Theatre of Louisville (KY)

Thomas Rodman, Alabama State University

Jonathon Taylor, East Tennessee State University

Chalethia Williams, Miles College (AL)

OUTSIDE THE BOX EDITOR

David Glenn, Samford University (AL)

THEATRE ON THE PAGE EDITOR

Sarah McCarroll, Georgia Southern University (GA) COLUMNISTS

Jonathan M. Lassiter, PhD, Lassiter Health Initiatives

Frederick Marte, B.A.M. Studio Ambassador

LAYOUT EDITOR

Scott Snyder, Muhlenberg College (PA)

ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Nikki Baldwin

NOTE ON SUBMISSIONS

Southern Theatre welcomes submissions of articles pertaining to all aspects of theatre. Preference will be given to subject matter linked to theatre activity in the Southeastern United States. Articles are evaluated by the editor and members of the Editorial Board. Criteria for evaluation include: suitability, clarity, significance, depth of treatment and accuracy. Please query the editor via email before sending articles. Stories should not exceed 3,000 words. Color photos (300 dpi in .jpeg or .tiff format) and a brief identification of the author should accompany all articles. Send queries and stories to: nikki@setc.org.

Southern Theatre (ISSNL: 0584-4738) is published two times a year by the Southeastern Theatre Conference, Inc., a nonprofit organization, for its membership and others interested in theatre. Copyright © 2023 by Southeastern Theatre Conference, Inc., 5710 W. Gate City Blvd., Suite K, Box 186, Greensboro, NC 27407. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part without permission is prohibited.

Subscription: Included in SETC membership. Join at setc.org

Single copies: $12 plus shipping

EIC Photo: Tracie Jean Photography

I have only a few words to describe the conference in Mobile, Alabama, in March. Wowie, Wowie, wow, wow! What a fantastic convocation to see such talented, committed, and inspiring theatre artists. The marvelous performances, the informative workshops, the inspiring keynote speakers, and the opportunity to connect with other theatre artists left me excited and refreshed as we work together to keep theatre a vibrant part of the cultural fabric of our country. For me, theatre is where communities are built, where empathy occurs, and humanity resides. That is why it is important for us as theatre artists to continue to band together and support each other. I am honored to be the President of SETC. It is an honor and a privilege to be asked to serve and I hope to continue the conversations and work of the organization in the areas of diversity, inclusion, accessibility, and belonging. I am excited for the organization as it continues to find pathways that lead to meaningful growth as both an industry and an art form. But it will take the whole community of artists to do so. I am looking forward to conversations about moving SETC forward, and how our industry adjusts to our current world and the opportunities of the future. We are moving forward! That is our mantra!

Jeremy Kisling (he/him), SETC President Producing Artistic Director, Lexington Children’s Theatre

As we convened at the 2024 Convention in Mobile, we celebrated not just the days of events but reflected on an incredible history — the 75th anniversary of SETC (Southeastern Theatre Conference). As a woman and African American artist and arts administrator, I’m reminded of the organization’s journey since 1949 and the broader narrative of American history. Born into the first generation to receive the full rights of U.S. citizenship, I’ve witnessed both progressive and disturbing residuals. From the Jim Crow era (named for an exaggerated, highly stereotypical Black character) to the pivotal rulings of segregation, the Voting Rights Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Feminist Movement, the Black Arts Movement, the LGBTQ+ Social Movements, the Anti-War Movement, the Disability Movement, Black Lives Matter, and the Me-Too Movement. These are just a few historical milestones close to our creative collective memory that has shaped our artistic world stage. SETC is an incubator for talent and empowerment, encouraging all artists to pursue their passions during challenging and good times, regardless. This energy fuels my determination to develop an organization that thrives artistically, provides a safe, supportive community, and delivers top-tier professional opportunities. We’re building a broader foundation set by those who came before us. It’s an endeavor worth every obstacle, sweat, and effort.

In celebrating our 75th anniversary, we recognize the historical landmarks that have shaped our journey—to this present time, where we strive for equity and inclusion at every stage of performance. My heartfelt thanks goes out to everyone who has contributed to this progressive legacy. Let us collectively continue to shape SETC’s future together. I am SETC. You are SETC. We are SETC!

Once in a while, a show comes along that is not only a scenic designer’s dream, but also one that could easily become a nightmare. A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams is one of those shows, and one that I first attempted to hand off to someone else as my respect for (and fear of) the scenic requirements of the play seemed just a little too daunting for me. Try as you might, it’s hard to escape Williams’s very specific and detailed setting descriptions. With limited time and resources, my task was to recreate a run-down apartment in the New Orleans French Quarter in the 1940s and somehow add a second story on our small stage. Of course, our director asked specifically for the cast iron railing that is typical of New Orleans architecture, and this is where I found myself completely stumped.

How in the world was I supposed to do that? I searched online, called all of my design mentors, and became distraught at finding zero solutions. The problem was that I had limited time, so the elaborate and tedious ideas that I was initially drawn to just wouldn’t work.

One late night as I was becoming increasingly desperate for an answer, I played some 1940s jazz, sipped on some bourbon, and closed my eyes, searching through the Rolodex of images in my mind of something, anything, that I could recall seeing somewhere in my life that I could use that already looked like a cast iron railing. Then it hit me! DOORMATS! They make rubber doormats that look like cast iron! And wouldn’t you know, I jumped on Amazon and found a variety of options that could be on my front porch in 2 days. Bingo!

My design process to plan out the railings was pretty simple. I saved the pictures of the doormats I ordered off the website, printed them out to scale through trial and error, then just cut them out into little puzzle pieces (the same way I’d chop up the mats when they arrived), and glued them into the arrangement that I thought would work.

The doormats that I ordered were conveniently sectioned off into decorative blocks of rectangles and squares, easily making the creation of the pieces I needed. Cutting the mats is not at all difficult (when you use the right tool). I first started off by using a utility knife, but soon realized that tin snips were the way to go. I used pieces of the decorative border to create fake iron facing for the steps going up to the second-floor balcony.

I built the structure of the railings out of scrap lumber. I love to save all sorts of “sticks” for projects exactly like this and rarely throw anything away. I chose to build these railings in a modular way, so that each piece (railings and columns) could stand independently of each other and be reused in the future in the same or different ways, much like big puzzle pieces.

I used little L-brackets to attach these pieces together. I attached the rubber mat sections to the fronts of these wood frame structures using construction adhesive and pneumatic staples.

I did a little extra online research to see what I could do to create an authentic looking surface to these railings. One technique that I found used by haunted houses to create fake iron fences was to mix sand into black paint to create a rough,

rusty texture. That was fun to try out. It also gave the railings a little extra weight and cut down on the floppiness of the rubber pieces. After installing them, our scenic artist added a little watered down, rusty orange over the surface to give it the final look.

This project was incredibly enjoyable, not all that difficult, and truly packed a punch in the end. The railings took lighting very well, especially with all the interesting negative space created by the decorative, ornate designs found in the rubber mats. I chuckled when a group of high school students were looking at the finished set and asked me where I found the iron railings. When I told them it was all just rubber doormats, one of the students said, “Prove it!” When I poked the front of one and they saw it wobble, their minds were blown! n

by Jonathan Mathias Lassiter, PhD

Dear Dr. Lassiter:

What are effective ways to “take a mental health day” for theatre students? Rather than staying in bed or taking a day off from their classes or production, are there things students can practice day-to-day which can allow them to stay functional as a member of a collaborative team?

Dear Reader:

The idea of taking “a mental health day” has become more popular in recent years as awareness of the importance of mental health grows among the general population. The Mayo Clinic defines a mental health day as “limited time away from your usual responsibilities with the intention of recharging and rejuvenating your mental health. It is an intentional act to alleviate distress and poor mood and motivation, while improving attitude, morale, functioning, efficiency, and overall well-being.”

According to their definition, a mental health day may be one day or several days away from one’s responsibilities. It could also be an hour or a half-day. Although we say mental health day, the time that we take to recharge and improve our mental health will vary significantly depending on our needs. Taking time away from one’s responsibilities to recharge has been found to contribute to the following benefits:

• Reduced feeling of burnout

• Improved morale and attitude

• Reduced isolation and loneliness

• Improved resiliency

• Improved physical health

• Prevention of a mental health crisis Clearly, taking a mental health day can greatly improve theatre students’ lives. However, taking a mental health day is not the only way or — depending on who you’re

asking — the best way to care for one’s mental health. Alongside the benefits can come disconnection from one’s community and responsibilities to others in that community, including one’s collaborative team.

Although mental health days may have emotional benefits, they are usually taken when one is already highly distressed. Thus, I recommend cultivating mental health from moment to moment in everyday life in all that we do. Thus, mental health is not a destination, it is a state of being that we can cultivate at any time.

This reframing may allow theatre students to think less of taking time off from responsibilities and focus more on shared responsibilities and humanity. For example, instead of retreating to one’s room and bingewatching Netflix to disengage, imagine the mental health effects of disclosing one’s distressing emotions to a trusted classmate or through a work of art.

The practice of living the principles of Ma’at may also help theatre students

Submit your mental wellness questions for Dr. Lassiter. Questions from students, theatre professionals, and educators are welcome, and you can request to remain anonymous if you prefer. Follow the link at solo.to/setc

cultivate mental health while approaching and not avoiding their responsibilities and the stressors that my come along with them.

The seven principles of Ma’at include: truth, justice, harmony, balance, order, reciprocity, and propriety. Living these principles will look different for each person. For example, living the principle of truth may look like a student speaking up in the face of injustice in the classroom or at rehearsal. Living harmoniously may look like working in collaboration, instead of competition, with one’s classmates. Living orderly may look like rearranging one’s life so that it is free of physical and psychological clutter. One may cultivate order by limiting social media use, removing people with negative energy from one’s life, and keeping a schedule so that one knows what to expect that day. Living the principles of Ma’at helps one structure their life in a way that is conducive to peace and deeper connections with others, which are all related to better mental health.

Mental health days are sometimes necessary. However, theatre students may find that they are able to achieve better and more consistent well-being when they refocus their efforts on nurturing their mental health in each moment. Connecting with one’s community — whether classmates, castmates, or other support systems — and living the principles of Ma’at have the potential to fortify theatre students’ mental health and lessen the need for mental health days by preventing psychological crises in the first place. n

by Frederick Marte

Saludo, buenas! Time to h@ndle your business. Since you’re an artist and you’re serious about your craft, you should connect with h@ndles that will add value to what your goals and aspirations are. What brings you joy? What are your values within the theatre world? When you know what your values are, you’ll be able to quickly identify your needs without being influenced by what others think or impose on you. Whether it’s performing, directing, arts administration, seeing musicals and plays, and/or devising pieces, there is an entire world of opportunities in the social media realm.

With that said, the two h@ndles that’ll be showcased are of an organization that engages with Theatre of the Oppressed and a pair of individuals who have become wildly popular entertaining film and theatre makers about the foibles (and sometimes absurd aspects) of the entertainment life. These social media accounts showcase what theatre can do besides entertain someone. They help you understand the benefits of knowing yourself within this industry. Remember, “El teatro es poesía que se sale del libro para hacerse humana. Y al hacerse

— Federico García Lorca *

Theatre of the Oppressed NYC

Instagram: @tonyc_action

X: @tonyc_action www.tonyc.nyc

“Theatre of the Oppressed NYC partners with community members at local organizations to form theatre troupes. These troupes devise and perform plays based on their challenges confronting economic inequality, racism, and other social, health and human rights injustices. After each performance, actors and audiences engage in theatrical brainstorming – called Forum Theatre –with the aim of catalyzing creative change on the individual, community, and political levels” (Theatre of the Oppressed NYC, 2019). Aside from providing resources to promote social change, you can also find information about relevant issues within the theatre field to help shape you into a multifaceted performer invested in the craft, but also how it connects to

the world and its social issues. Theatre of the Oppressed NYC is based on Augusto Boal’s work, who was inspired by Paulo Freire’s work and book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970s). Theatre is meant to cause the audience to engage in activity or think deeply about a topic, so connecting with @ tonyc_action will expose you to innovative ways of incorporating aspects of the “real” world within your craft and how to enact change.

Booked by @bodycourage & @lanisafrederick

Instagram: @hashtagbooked www.hashtagbooked.com

“Hashtag Booked, featuring LaNisa Frederick and Danielle Pinnock, is a groundbreaking online series examining the joys and misfortunes of being an actress of color in the entertainment industry” (Hashtagbooked, 2019). These two creatives are essentially using their platform to provide space to give consumers the ins and outs of the industry as it pertains to being Black and a Woman. You’ll find sketches that are relatable and extremely funny as well as information and resources on getting involved in relevant causes. Although you will have a good time watching this duo, the goal of being connected to them is to see how loving yourself and walking in your truth can help create opportunities for you that you may not have thought of. Sometimes the goal is to be in the industry, but the dream becomes something more satisfying once it aligns with who you are at your core. n

* Theatre lets you express yourself fully and you can only do that once you truly know who you are and what you want!

Frederick Marte (he/him) is an Official Ambassador for the Black Acting Methods Studio. He teaches theatre in NYC, and was the 2022 Programming Intern with the Black Theatre Network. @fredericktalks

Recipient S. Epatha Merkerson remembers the challenges on the way to becoming an icon

When S. Epatha Merkerson encounters a fan, she can instantly tell which of her roles they are most familiar with. If they are fans of Reba the Mail Lady from Pee-wee’s Playhouse, they expect a disarming smile and easy friendliness. After all, she spent six years delivering laughs and jokes with Paul Reubens, Mr. Pee-wee himself. But if they have encountered her as Lt. Anita Van Buren on Law and Order, a role she played for 17 consecutive seasons from 1993 to 2010, she might get a cooler reception.

“[They] think that I’ll be cut and dry,” she explains, “to the point, all business.”

In a career that has spanned Broadway, film, and television, she has been honored with numerous awards including a Golden Globe, an Emmy, a Screen Actors Guild Award, two Obie Awards, four NAACP Image Awards, Black Theatre Network’s Pioneer Award, four honorary doctorates, and most recently a 2024 Distinguished Career Award, which was bestowed at SETC’s 75th Anniversary Conference in Mobile, Alabama, on Saturday, March 16, by SETC Executive Director Toni Simmons Henson.

For those who were fortunate enough to attend the SETC conference, Epatha mapped some of the highlights of her career through a slide-show presentation that she created especially for the occasion. NYU professor and playwright Michael Dinwiddie, who had the honor of interviewing her, shared their history together beginning as students in the BFA acting program at Detroit’s Wayne State University, where they met in the 1970s.

A native of Detroit, Epatha is the youngest of five children in a family that is nurturing, artistic and musical. “My father gave me the name Epatha,” she explains, “which is what I prefer to be called. He was influenced by a school teacher who inspired him to continue his studies.” Her mother Anna, who passed away recently, spent decades singing in her church choir. “My sister Linda was a dancer in high school, and I remember my mother taking me to see her in a concert. It was amazing to watch her float across the stage. My brother Barrie is a lawyer in Detroit, but as a teenager he played in a band called the Soul Busters. My sister Debbie was in a doo wop group.” Of her childhood, she recalls, “They thought I was crazy! I was always dancing around the house!” But no one in her family expected her to pursue a career in the theatre, least of all her mother. “She refused to pay for my schooling because she didn’t think it was wise for me to major in.” But Epatha was determined to follow her dream. “So I said, okay — and I decided that I would work and pay for college myself, which I did.”

‘I tried very hard’

Even from her high school days, Epatha knew that she would have a career on the stage. “I credit my teachers as role models and mentors. I wasn’t a great student, but I tried very hard.” She recalls with fondness Carolyn Hardy, a junior high school dance and gym teacher. “She was the first woman I knew who had an Afro!”

There was one special event that Epatha recalls fondly to this day. “It was a poetry slam, with the artists on the stage in a circle. And each poet would start their poem. And Miss Hardy told me to go into the middle of the circle and improvise, just start dancing. I said okay. And it was so wonderful!”

Epatha received a special lesson from that experience. “I understood the freedom that you need to have as an artist. I also learned the importance of mentors.”

While working her way through college as a waitress, a co-worker convinced her to take a theatre elective with her. As a result, she was assigned to stage-manage a college production, where “it soon became apparent that the lead actress was not working and was about to be replaced. So I told the director that I thought I could do the role and I was given the opportunity.” That was Epatha’s first stage role, and the experience convinced her that theatre was a place where she could thrive.

At Wayne State University, Epatha studied under Martin Molson, the only African American theatre faculty member there. “Marty cast me in a studio production of Jean Genet’s play The Blacks, and he would use me for demonstrations in his master classes.” She also sang and danced in mainstage musicals such as George M! and Purlie. She recalls, “I was asked not to audition for the role of Lutiebelle in Purlie, since the role was already promised to a senior.” So Epatha choreographed the show and found opportunities working with her classmates.

“This was the era before non-traditional casting, so nearly all of my work was in student productions and recitals.”

I understood the freedom that you need to have as an artist.

by Michael Dinwiddie

After graduating from college, Epatha admits, “I didn’t have the confidence to go straight to New York City, so I went to Albany and worked with a children’s theatre company. They were producing The Miracle Worker, and I was excited by the possibility of tackling a meaty role like Annie Sullivan. Instead I was cast as Viney, the Keller family

servant, and later assigned to dance in musical revues… Can we just say, to date it was the worst job I’ve ever had?”

Frustrated, Epatha took the leap and moved to New York in 1978. “The first person to hire me was George Faison, the Tony Award-winning director of The Wiz.” Later, Epatha was Lonette McKee’s understudy in the one-woman show Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar and Grill When Lonette left the show, Epatha stepped into the role. “Before I went on, I had to learn 15 songs and 48 pages of words in six days. I had never seen Lonette’s performance, so I had to create from what I knew of Billie’s life. And the director and I did not see eye to eye. But by the time we finished, we had connected.” One evening, casting agent Meg Simon saw the play.

Impressed by Epatha’s performance, Simon recommended her to director Lloyd Richards, who was touring August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson at the time. The lead actress was leaving to do a movie, and “I was brought in with just nine days to learn the role of Berniece before we opened at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago.” She goes on to say, “The other actors had been working together for quite awhile, so I had to prove myself.”

They also enjoyed pulling stunts that would send her into laughing fits during rehearsal. Luckily, lead actor Charles Dutton pulled Epatha aside when Lloyd Richards expressed his displeasure at her seeming lack of concentration. “I know you guys can deliver,” Lloyd stated, “but I don’t know about her.” Epatha realized that her job was on the line. “That night I concentrated and the cast was behind me,” she says. “No more jokes and the show went very well.”

Richards was impressed and Epatha went on tour to San Diego and Houston, all the while with August Wilson revising the script. “We were on and off the road for three years before we went to Broadway. The whole end of the first act changed two days before we opened in New York.” The play went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, and

Epatha was nominated for a Tony Award as Best Featured Actress in a Play.

Soon after, Epatha got a call inviting her to audition for a new TV show, Pee-wee’s Playhouse. “I was on my way out the door, so I picked up all my mail and stuffed it in my satchel.” She arrived at the audition and asked for “sides,” pages pulled from a script to see how actors would read for various roles. “I was told that there were no sides, and I should just go in and improvise.”

All she could learn about the role was that it was for a mail lady. So Epatha quickly opened her satchel filled with her personal mail and started peeling out the pieces. “Here’s the utility bill,” she ad-libbed, “and here’s the phone bill, and here’s something from the Museum of Natural History — and I started singing ‘Dem Bones.’” She was stopped by the casting agent, who was not amused. She was told to play it straight. But Epatha was having fun, so she kept pulling out her mail and comically pulling open the envelopes, adding sound effects and crazy moves.

Two weeks later, when she had not heard from the casting agent, she thought, “I messed that up.” But she did receive a call back from the casting department shortly after she had given up. “This time I was introduced to the director, the producer, and this bearded guy named Paul who looked like a hippie.” She and Pee-wee’s Playhouse star Paul Reubens were paired together to audition, and his antics had her in stitches. She pulled him aside and quietly said, “Stop making me laugh. You’re gonna make me lose this job.” He smirked and said, “I don’t think so.” But he realized that Epatha wasn’t convinced. So he continued, “You can’t lose this job, because the show is called Pee-wee’s Playhouse.” He modulated his voice to a high-pitched squeak as he proclaimed, “I’m Pee-wee!” Epatha was shocked and pleased. But she learned from that experience “to always know who I am auditioning for — and with!”

As an actress whose career slowly gained momentum, Epatha did a number of pilots and films before landing on the show that made her famous. “I did an episode in the first season of Law & Order in which I played a mother whose 11-month-old child is killed.” Two years later when they were bringing women into the precinct, “executive producer Dick Wolf remembered me and called me in for a meeting.” The word came back that “I was ‘saturated’ on television because I had done so many projects with my natural hair. So I went home, took the twists out of my hair, brushed it back into a ponytail, put on a bow, and walked into the meeting. When I showed up, Dick Wolf took one look at me and started laughing. ‘That’s her,’ he exclaimed, ‘that’s Van Buren!”’ Epatha did not know at the time that Wolf’s children had been big fans of her character Reba the Mail Lady on Pee-wee’s Playhouse

Bringing an important perspective

In doing her research for Anita Van Buren, Epatha learned, “There were only four women lieutenants in all the boroughs.” She was fortunate to meet Lt. Barbara Sicilia, head of the New York City Midtown North Precinct. Her first impression of Sicilia, who met her outside the precinct, was “that she had short black hair, wore a shirtwaist dress, and had a pleasant smile.” But the minute they walked through the door, “Everything changed. You could see the men straighten up as we walked by. I knew that this was Van Buren! She had to be strong. Miss Thing was fierce!”

When they stepped into Barbara’s private office, she looked at Epatha and started giggling. “You have to tell me what just happened,” Epatha implored. And Barbara Sicilia answered, “I’m their lieutenant. This is between you and me. But when I walk out of this door, there’s no playing around. They know I’m the lieutenant!”

Epatha appeared on 395 episodes of Law & Order. “As a Black person, and as a Black woman, I know how important it is for

S. Epatha Merkerson in two of herbiggestTV roles: as Reba the Mail Lady on Pee-wee’s Playhouse (with Paul Reubens), and as Lt. Anita Van Buren on Law & Order.

my roles to be focused in a positive light, a truthful light.” She was able to have an impact on the show as it evolved. “I was a voice at the roundtable,” she states. “We had Jews and Gentiles, males and females, Blacks and Whites, young and old. It was literally a microcosm of the world. The writers were men who had spent years working in district attorney offices and knew the law inside and out. But none of them were women, and none of them were Black. I brought that perspective to the show.”

In one telling episode, she invited some of her friends to attend a taping of the show. “Fran Lebowitz, Toni Morrison, and Sonia Sanchez came and hung out all day.” When Toni Morrison glanced at the wall of the TV set with pictures of criminals, she asked, “Why are all of the perpetrators Black?”

Within minutes, several people were scurrying towards the board and making a more multi-cultural display of New York criminality. Epatha and Toni looked at each other, pleased at the impact of Toni’s words.

As an actor, Epatha believes, “The theatre is really the basis for me. Every other year I try to go back to the stage, because there’s something about being onstage that you don’t get when you’re doing film or television.” She met Billy Porter, the Tony Award-winning star of Kinky Boots when they both appeared in Cheryl West’s play Birdie Blue. “Billy told me, ‘I’m writing this play about my life, and I want you to play my mother.”’

Then Billy presented the play. “I was thrilled to play Maxine, a woman who must deal with physical challenges and the emotional upheaval caused in her life when she learns that her son is gay.” Fondly recalling the journey, Epatha

states, “It was a beautiful play, and I was honored to create the role.”

One of her most fulfilling experiences was creating the role of Rachel “Nanny” Crosby in Ruben Santiago Hudson’s Lackawanna Blues . “I saw it when Ruben was doing it as a one-man show at the Public Theater, filling up the stage with all these amazing people from his childhood in Buffalo.” Ruben mentioned that HBO had bought the rights and there might be a part for her. Once she finished her audition, the director George C. Wolfe gave her the heads up: “This is your part.” She was elated.

“I knew that I could really bring the role of Nanny alive.” Playing an independent Black woman who becomes the stable figure for a young Ruben in a boarding house, Epatha had the opportunity to bring all her strength and passion to that meaty role she had always been searching for. Aside from the critical acclaim, she earned numerous awards and accolades for her outstanding performance in Lackawanna Blues

Today, the veteran actress continues to entertain audiences as she enters her tenth season on Chicago Med where she plays Sharon Goodwin, the Director of Patient and Medical Services at Gaffney Chicago Medical Center. Epatha has had the unique experience of playing the Sharon Goodwin character in three different series: Chicago Fire (2012), Chicago P.O. (2014) and Chicago Med (2015).

‘Make sure you have fun’

Epatha splits her time between New York and Chicago. She offers encouragement to young artists who are striving to have careers — on stage, on film, or behind the scenes as directors, designers and technicians. An advocate for self-care, she is open about the health challenges she has faced. On Feb. 4, 1996, she quit smoking after 23 years. And in 2003 she was diagnosed with type two diabetes, which she carefully manages with diet and exercise. When she rises to acknowledge the applause at the end of her SETC keynote interview — is it Reba the Mail Lady or Nanny or Anita Van Buren or Sharon Goodwin we see? No. It is S. Epatha Merkerson in the flesh, inviting her audience to “take care of your instrument and know your worth!” Her parting message to SETC members of all ages who embark on this wondrous journey of a life enriched by the arts: “Make sure that all along the way, you have fun!” n

Three designers were featured as part of the 2024 Panel of Distinguished Designers at the SETC Annual Convention in Mobile, Alabama. Each designer brought their unique stories and experiences to the Design Keynote on Thursday evening, sharing hopes for the future of theatre, insights into the state of the industry, and advice for students who will soon enter the field.

by Jonathon Taylor

Beowulf Boritt is the Tony Award-winning set designer for James Lapine’s One Act His design for Susan Stroman’s production of New York, New York also won a Tony as well as Drama Desk and Outer Critic’s Circle Awards. Several of Boritt’s other designs have been nominated for the Tony Award including POTUS Flying Over Sunset, and Therese Raquin Boritt also founded and manages the 1/52 Project, which aims to diversify the Broadway design community by providing financial support for early career designers from historically marginalized or excluded groups. His book, Transforming Space Over Time, is available on Amazon and through Bookshop.org.

Prior to the conference, Boritt was eager to talk about the 1/52 Project. Citing the influence of the #metoo movement and #weseeyouWAT as indicators of the “need for more equity across the industry,” Boritt acknowledged that these social movements were integral in pushing him to want to give back from his position within the industry.

“We give $15,000 grants to young designers to help them along in the early years of their careers, and one of our recipients from the very first year had her Broadway debut last year. So there’s some evidence that it’s helping.”

“When the room is more mixed both with gender and ethnicity you just get a wider perspective. One of the magical things about theater is that it’s all these people putting their heads together to create something on stage, and the more diverse those heads are, the stronger, more interesting, and richer the product is going to be.”

Boritt’s work with the 1/52 Project continues, supported by the contributions of other Broadway designers, artists, and professionals — another example of theatre artists putting their heads together to create something magical.

Boritt said he was ambitious when he entered the field, and conceded that the industry is competitive and that success comes as the result of a lot of work. However, he cautioned early career designers against setting artificial deadlines. “You don’t need to conquer the world by the time you’re 25 or 30 or 35 or whatever. Life doesn’t really work that way… Some people think that those kind of markers are important but I would say give yourself a break and don’t put artificial deadlines on yourself.”

Boritt emphasizes the importance of communication and making connections with people.

“We’re a social species, and if you know how to deal with people and show up and network… you will do better at whatever you do, but particularly as a freelancer. [Making connections with people] is your lifeblood. It is the only way you’re going to keep working” in the commercial theatre.

“Be a pleasant person, and [don’t] be a jerk.”

Boritt advises early career designers who are interested in working as assistants or associates to be “self-starters, somebody who has enough sense of how fast they can work and what they’re doing” so that deadlines can be met.

“You can’t be flaky. You’ve got to show up on

time and be willing to put in the time,” something he admits may seem to go against the grain of the younger generation’s desire for work/life balance.

“We all need to find that [balance] for ourselves, but I don’t think the theater is a nine-to-five job. It has not been in my experience. I want assistants who are willing to put in a long day when that’s what’s needed, but when the show is going well and everything’s fine I’ll send them home early.”

Boritt also encourages early career designers to keep up with current technology. “The more you know, the more you know—and the more marketable you are.” Understanding current model-building techniques, CAD programs, 3D printing, and laser-cutting are just a few of the specific skills he mentioned.

“The broader your skillset, the better.”

Erik Teague is a freelance costume designer based in Washington, D.C., who is originally from Georgia. Previous works include A Midsummer Night’s Dream , As One , The Threepenny Opera and Cabaret (The Atlanta Opera); The Cunning Little Vixen , La Bohéme Ariadne in Naxos , The Jungle Book , Odyssey, Wilde Tales, Trouble in Tahiti , The Flying

2023

Dutchman (The Glimmerglass Festival); and Lohengrin (Opera Southwest). In addition, episodes from Teague’s podcast series that center LGBTQ+ opera artists, Come As You Are, are still available on The Atlanta Opera Podcast.

Teague is the winner of one Helen Hayes Award and two Suzi Bass Awards for excellence in costume design.

During the keynote presentation on Thursday evening, Teague encouraged early career designers to “[be] present in the moment and ready to accept the “yes, and” when presented with an opportunity—whether that’s an internship, a job, or just a conversation.”

By way of introducing himself, Teague underscored the importance of developing his craft. “When I got into school I was a voracious devourer of all kinds of art — anything that piqued an interest.”

Teague described taking classes in his field of study and working in the costume

shop, but emphasized the impact of working closely with a faculty mentor. “In my freshman year, I started assisting one of my professors with his off-campus work. I’d go to class all day, go to the shop in the afternoon, and then get in the car and go downtown.”

Teague admits that sometimes the assistance he provided didn’t seem very important. “I might not be doing anything more important than taking shoes up three flights of stairs and taking notes, but I was there and I was listening and I was watching the interactions in those fittings and seeing how performers lit up when they both had a shared idea.”

“Being a fly on the wall is an important part of the early business. Getting in the room is crucial.”

After suffering a personal loss that nearly derailed his career before it began, Teague told the story of his uncle, who supported his dream of working as a theatre artist and pushed him to continue working toward his goals.

encouraged early career designers to cultivate communication skills.

Acknowledging that public speaking can often feel terrifying, Teague says that “sometimes the difference between getting a project greenlit or ignored is a good pitch, and that pitch is never going to happen in a formal setting. It’s usually going to happen in a random conversation somewhere on the street, at a bar, at a party, or in an elevator. So, just be ready for a moment’s notice and practice” communication skills.

Underscoring the importance of collegiality and self awareness, Teague says, “Be kind and compassionate to everyone you work with.”

“Be true to yourself. We are storytellers and our life experiences influence our work. It is crucial that we all tell different stories. Otherwise it gets really boring. So you can be a meaningful part of this industry while being honest and open about who you are.

“Everybody needs somebody like that in their corner. Whether it’s chosen family or blood family doesn’t matter. Surround yourself with people who are going to help you [and] who believe in you — who believe in your goals — and can help you keep moving, even when you can’t see the way.”

Teague also

Rachael N. Blackwell is originally from Virginia and now resides in Atlanta, GA. She describes herself as a creative who is interested in working collaboratively with other creatives across different art mediums. Blackwell enjoys working on original and new works, particularly those that allow her to stay connected to her African American roots.

In 2020, Blackwell received the Gilbert Hemsley Lighting Internship and won the Judy Dearing Design Competition for Lighting, presented by the Black Theatre

Network (BTN). In 2021, Blackwell received an Off Broadway nomination for her New York lighting design of the new musical Rathskeller: A Musical Elixir Blackwell currently works full-time at the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta as their Lighting & Projections Director.

When asked about advice for early career designers, Blackwell immediately underscored the importance of exposure—of putting oneself out there—but advised that it wasn’t necessarily the most important factor.

“I think just as important [as exposure] is not letting anybody put you in a box… If you’re fresh out of college — undergrad or graduate — and you consider yourself a designer and that’s all you want to do — great. But if not—if you’re a designer or if you’re an artist or creative in general — I think you should go out and do what makes you happy. Do what makes you feel fulfilled.”

“Passion projects may not always be what you studied in school [or in] class. If you’re a designer you may find fulfillment assisting a director or working in the scene shop. I think exposure is just important as [doing] the work that you went to school” to study.

Blackwell emphasized the importance of making and maintaining connections with mentors. She names a number of mentors she’s met throughout her career, but describes Kathy Perkins as her “biggest mentor.” Perkins is a black female lighting designer that Blackwell met the first time she attended USITT in 2012. “[Perkins] has just poured so much into me over the years—whether it’s experiences like allowing me to assist her or handing me work that she was unable to do — and now I feel like we’re just really good friends. I can call her and talk to her about anything whether it’s lighting-related or life-related.”

When thinking about skills needed for new artists entering the field of design, Blackwell didn’t hesitate. “There’s soft skills and there’s hard skills.”

Blackwell lists drafting, programming, and knowledge of current technology as some of the hard skills she finds important, but soft skills are just as important for early career designers and potential associates and assistants.

“I’m looking for somebody who’s just willing — willing to learn, willing to ask questions, and who is willing to get a little dirty if we’re on a lower budget show and we’re wearing multiple hats in the lighting realm. I’m looking for...somebody who can work well with others, who can listen and take directions and pays attention to detail. All those things.”

Recalling the pandemic pause and its resulting effects on the industry and creatives, Blackwell found some good in the midst of the closures necessitated by the COVID-19 outbreak.

“In general, the pandemic allowed artists to just take a pause. A lot of us (and I’m specifically referencing myself) can be workaholics or go nonstop, especially if you’re in the freelance lifestyle. It can be a bit of a grind, and I think the

pandemic forced us all to reevaluate the importance of mental health and physical health. [It forced us to] be as intentional about those pauses as we are with our work.”

If Blackwell has a wish for future designers and theatre artists, it’s that they return theatre to some of its roots.

“People are trying to create staged films instead of theatre...We have film for a reason. We have TV for a reason. We have theater for a reason. And I think people are losing sight of what theater is supposed to do because of all of the frills and the bells and whistles.”

“I’m hoping that in the future we get back to theatre.” n

“History doesn’t feel like history. It’s just hard work and engagement on an ordinary day.” —Toni Simmons Henson

Some say the South is the new East Coast; that there is a renaissance of artistic expression happening and its energy is coming from the South. Well, if this year’s 75th celebration of SETC is any indication, we are in full swing of that renaissance. SETC’s Convention looked and felt different than before, it felt uncharted and new, signaling fertile ground for the creation of wonderful work and beautiful collaborations.

I attended my first SETC Convention as a volunteer 10 years ago. I volunteered so that I could get a “lay of the land” and discover the inner workings of the largest theatre conference in the country. The difference in the 2024 Convention was palpable, not in a negative way, but in a way that made room for more people with varying entry points to the work, the art, how it’s made and why. This new era of SETC is truly exciting.

It was a far cry from where I was originally reared, which is South Central Los Angeles, California. What I found and continue to find comforting about living in Atlanta, Georgia, is that it feels like home, like Natchitoches. Atlanta feels familiar. I know the people and the food. I know the music and the rhythms. I know the shared history of the Civil Rights Movement. Atlanta and the South have always felt like home. In many ways, this year’s SETC Convention also felt like home — and in all honesty, after attending several previous SETC conferences, this is the first time that I felt at home. I saw an SETC community in celebration of a future they aren’t so sure of, but they still felt good to be in the moment without judgement or agenda.

I have always had an exciting time at SETC. I am like my mother, in that I have never met a stranger. I will find a tribe in any setting, but that isn’t everyone’s strength. How do you create an event, a convention, where everyone feels seen at some point and that everyone is encouraged to celebrate … seeing? That was achieved this year. At this year’s Convention I had the agency to be involved. I had agency to not stand on the sidelines, but to come in and join the mechanism that is SETC. How did SETC accomplish this? One way was by inviting artists into the space whose likeness has traditionally been under-represented at past Conventions. This year, I had the pleasure to witness three African-American artists partake in a new era at SETC. They are Freddie Hendricks, S. Epatha Merkerson, and Sharrell D. Luckett. What follows are my thoughts on their presence and their impact which I hope highlights how important it is for SETC to continue diversifying their pool of invited guest artists.

right time to have him welcomed and honored at the annual gathering.

by Keith Arthur Bolden

If someone had told me that I would be living in the South as an adult, I think I would have been just fine with that. The reason: my parents always kept their connection to their hometown of Natchitoches, Louisiana — the oldest Parrish in the state. I would visit during my childhood, sometimes spending months there.

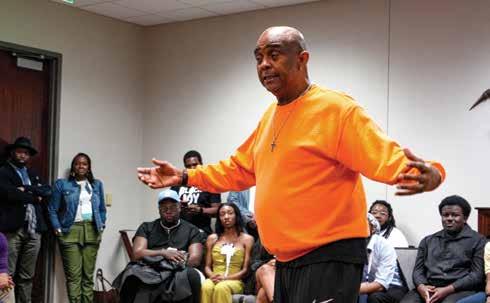

Freddie Hendricks is a legend in and around Atlanta. His influence can be felt on stages and screens all over the world. He has helped to shape and launch some of the careers of the most talented artists you will see on stage and screen. Some of them include Enoch King, Christine Horn, Dr. Sharrell Luckett, Kerwin Thompson, Saycon Sengbloh, Omar Dorsey, D. Woods, and Kenan Thompson, to name a few. This was Freddie’s first SETC Convention and without the leadership of Toni Simmons Henson, I do not think he would have ever attended. His influence is undeniable in the Black artistic community and SETC felt that this was the

SETC is great at creating affinity spaces for the varying groups that attend each year. This year saw the largest number of African Americans to attend the conference, in large part because of the HBCU (Historically Black College and Universities) grant initiative to help underserved performing arts students attend the event. In the HBCU affinity space Freddie was introduced and it was apparent that he was on fire with energy from the first night of the conference. He entered that room with a song in his heart and a message in his speech. Most of the over 75 students in attendance were not aware of who he was, and by the end of his call to action, his call to craft, his call for community, they could not get enough of him. There were exchanges of photos and contact information, and with that SETC did what it does best: provides a platform to artists who may never have one, to recognize artists that we may be unaware of, and to give flowers to the artists while they are still with us pouring into the next generation. That is what Freddie Hendricks is all about.

Freddie co-founded the Freddie Hendricks Youth Ensemble of Atlanta in 1990. Now just known as the Youth Ensemble of Atlanta (YEA), YEA has become the south’s premiere African American youth theatre company. YEA has helped countless young people to better their worlds using the arts. The organization has fostered the personal growth of hundreds of young people from childhood to adulthood.

History doesn’t feel like history. It’s just hard work and engagement on an ordinary day.

— Toni Simmons Henson

YEA has helped talented and dedicated performers develop critical communication and life skills, raise cultural awareness, pledge commitment to excellence and community service, and appreciate diversity. Inspiration is always welcome at SETC and it is even more inspiring when it comes from something or someone familiar. That is the power and necessity of affinity spaces.

SETC saw several firsts in its 75th year. My dear friend Michael Dinwiddie attended his first Convention. He is a brilliant professor at NYU’s Gallatin School and an award-winning playwright (from Detroit) who was in attendance to interview the Distinguished Career Keynote Speaker, S. Epatha Merkerson (also from Detroit), who was also attending her first SETC gathering. Those in attendance were treated to a delightful and engaging conversation between old friends, which in turn made us feel like old friends and not simply audience members. It was truly like sitting and listening to two friends talk over their shared histories and inside jokes. Dinwiddie’s interview approach was conversational, which made the already extremely comfortable in her own skin, S. Epatha, even more open. So much so that she even shared with us

that the elegant and tasteful ensemble she was wearing, was indeed from wardrobe and the character she portrays on Chicago Med , Sharon Goodwin. S. Epatha jokingly shared that she hasn’t bought clothing in nine years, because, “Why should I? When you go on set, you are taking off your clothes to put on your character’s clothes. So why buy clothes when you are going to take them off?”

S. Epatha Merkerson has been a professional actor on stages and screens for over four decades. She has made her indelible mark on Broadway, being nominated for a Tony Award twice, one of them being for a role in August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson, which she took over from another actor who was shooting a film during the play’s trial run in the regional theatres. She recalled that she had nine days to learn the play with actors who had already completed two extended runs, one at Yale

Repertory and the other at Huntington Stage Company. And on the 10th day she was on stage at the Goodman Theatre, working with Lloyd Richards, who was the director of the production and was one of the most influential artists that August Wilson ever worked with. She finally had the chance to collaborate with Richards, an opportunity that seemed to evade her for years. S. Epatha exclaimed “[for a time] I couldn’t get arrested by Lloyd Richards.”

S. Epatha has also made her mark on the screen by embodying the central character in Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s Lackawanna Blues, directed by George C. Wolfe for HBO, for which she won an Emmy, Golden Globe, and several other awards. Lackawanna Blues is a film that began as a one man show by SantiagoHudson and an ode to his dear Rachel “Nanny” Crosby, the mother figure who

raised him and the cast of characters who resided in the boarding house that she owned in Buffalo, New York. Upon hearing of the upcoming film, Ruben told S. Epatha that he thought there may be something in it for her. She never imagined that she would be the main character for which she would be lauded for embodying and ultimately sweeping the awards season.

Ultimately, S. Epatha Merkerson shared life lessons of doing the work and not fighting every battle. She also cherishes her engagement with theatre. Every few years she does something on the stage because it keeps her grounded and she emphasized that the stage is the best training ground to learn to build character and learn how to create an arc for that character.

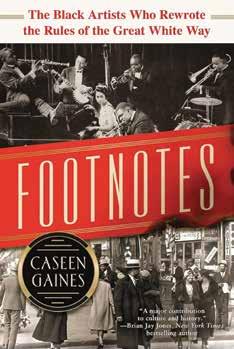

The brilliant Sharrell D. Luckett is making her impact on the theatre world by influencing the way actors learn, how they learn it, what they are learning and who is teaching. She is the lead editor of Black Acting Methods: Critical Approaches and the founder and creator of the Luckett Paradigm, which is a “performance methodology where practice and theory

Artistic intersections in the theatre world are far reaching. The Luckett Paradigm is influenced by the work of Freddie Hendricks (b.1954) who is “an African American theatre director and teacher who creates full-length musicals and dramas with youth and young adults, often without a script. Hendricks trained students primarily at the esteemed Tri-Cities High School in Atlanta, Georgia, and in his theatre company, the Freddie Hendricks Youth Ensemble of Atlanta.” (www. BlackActingMethods. com)

This year sawthe largest number of African Americans ever to attend the conference. “

Acting Methods: Critical Approaches “offers alternatives to the Eurocentric performance styles that many actors find themselves working with on stages and screens across the country. These alternative approaches are rooted in a critical framework that allows Afrocentric sensibilities and experiences to excite and invigorate approaches to performative scholarship.” (Black Acting Methods, publisher description).

What is exciting about Sharrell and what she has created and continues to develop was born out of a need, a necessity due to an abundance of lack.

are guided by four overlapping, intersecting Afrocentric dimensions: Corecreation, Orientation, Dialogic Devising and Resuscitation. The Paradigm involves empowered authorship, musical sensibilities, spirituality, activism, ensemble building, reverence of Black culture, and creation without a script. In addition to focusing on the breath, the body, confidence, mental health, and imagination, The Luckett Paradigm also:

• develops culturally grounded, and versatile actors who can work and create with or without scripts.

• is trans-medium, making it applicable to performance in theatre, television, and film.

• nurtures spiritual aspects of the creative process.

• assists actors in developing and applying psychological tools for cultural affirmation and resilience in the audition rooms and acting studios.

• encourages activist and social justice work in and with performance.

• values the complexities and challenges of what it means to be a working Black actor in America.” (www. BlackActingMethods.com)

At SETC I had the privilege of having a conversation with Sharrell as she was one of the conferences Distinguished Keynote speakers. Sharrell spoke candidly about the popular acting methods and its teachers and how we, collectively, are all too familiar with their work (Sanford Meisner, Uta Hagen, Jerzy Grotowski, etc.) in contrast to the people of color who have also had significant impact in their communities through their artistry and methods, such as Freddie Hendricks, Cristal C. Truscott, Justin Emeka, Daniel Banks, Kashi Johnson, etc.) — and most have never heard of them. The lack of awareness and curiosity is what prompted Dr. Luckett to embark on the journey of co-editing the book, Black Acting Methods: Critical Approaches. The pandemic and the effect it had on the industry was a primary catalyst for the book becoming a #1 best seller in the field of theatre. The popular book stayed at the top of the Amazon best seller list for at least eight weeks. Around this same time, Luckett began training actors and educators virtually through her acclaimed institution: The Black Acting Methods Studio. When the book shot to #1 there was a sudden huge demand for her to teach what she had written about. Black

She is a scholar, practitioner, and visionary whose eyes are on the future of the way that art is made in the theatre.

I am delighted that I had the opportunity to witness these three invited guests and their offerings. The 75th Anniversary Convention was the most inclusive and productive SETC that I have attended.

During my last night at the Convention, I sat around a piano with an amazing pianist and sang Motown songs with all the guest speakers. If someone had told me years ago that I would grow up and sing Motown songs with S. Epatha Merkerson, in the south at the largest theatre conference in the country, not only would I not be mad at that, I would have made it happen much sooner. n

by Amy Cuomo

On March 13, the Southeastern Theatre Conference’s Teachers Institute introduced arts advocate Howard Sherman, who began his workshop with a series of questions.

• “Have you ever had the experience of having a show canceled over content?”

• “Have you proposed a show to the administration, and had it shot down?”

• “Are there shows that you know are right for your students, but you don’t suggest them because they will draw an unfavorable response?”

• Hands raised and discussion regarding censorship of high school and college productions began.

Shows such as Mean Girls, She Kills Monsters, Sister Act , and Oedipus Rex made the list. Sherman noted that the most remarkable thing about censorship is that it could happen to any show. Because of his vast experience in the theatre, Sherman found himself in a unique position to help with the problem. Howard Sherman’s career in theatre has

know about these situations. It snowballed in ways I never expected.” So, the incident in Waterbury, along with several other incidents, encouraged Sherman to develop a workshop to help educators prepare for and react to the possible censoring of a theatre production. Sherman insists that he’s not an expert, but he does have a special set of skills. He noted, “I know a lot of people in the theatre. I know a lot of shows, and I worked as a publicist, and I have a big mouth.” In addition, Sherman has a wealth of experience in the theatre world and in dealing with incidents of censorship. He stated, “One thing I bring to the table is that this is not my first time. When [censorship] happens to people, it blindsides them.”

been a labor of love. In the past, he has served as executive director of the American Theatre Wing, managing director of Geva Theatre, general manager of Goodspeed Musicals, and public relations director of Hartford Stage.

Sherman has spent over 40 years at the heart of the industry. Ironically, he fell into arts advocacy by accident.

Thirteen years ago, Sherman wrote a blog post about a production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone that was canceled in Waterbury, Connecticut. He knew August Wilson’s work and had attended the production in New Haven when it premiered at Yale Repertory Theatre.

In an unlikely turn of events, Sherman, along with folks at the Yale School of Drama, worked successfully to have the show restored.

Sherman explained how his work evolved.

“There had been enough attention to the Joe Turner situation that I started getting calls.

Social media makes it possible for people to

to contextualize them so that audiences can understand the importance of the work. In the workshop, Sherman drew a series of concentric circles on a flip chart. From the center outward, the text read: Students involved in the show; other students in the school; parents; other family of students; and finally community. Nowhere on the circle were the words teacher or administrator. Sherman stipulated that the reason to produce a work is primarily for the students involved.

board with the production. One way to start this process is to collaborate. In an exercise, teachers brainstormed strategies for building context for a show. A few of the ideas were:

• Work collaboratively with students and parent groups, such as booster clubs, to select and promote the production.

• Work with the students to talk about potential risks of the show.

• Send out a parental agreement regarding content.

Sherman’s approach to arts advocacy emphasizes collaboration, networking and treating each case as unique. He maintains that he is not the only person working on problems of censorship. The Dramatist Guild, the American Civil Liberties Union, the National Coalition Against Censorship, and The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) all strive to protect artists ability to express their ideas. The “how” of restoring a show that has been canceled takes a variety of forms. “Sometimes what is needed is a big public campaign,” Sherman explained. “Sometimes what is required is a conversation behind closed doors that no one will know about.” Through it all, however, Sherman insisted, “It is of paramount importance that a teacher isn’t put at risk.” When working on restoring a show that has been closed, Sherman says, “when things go public, it is only because people want it to be public. You don’t always have to make a public fight; the people come first.”

When selecting a play to produce, the questions to ask are: Why this show? Why now? What is it about this show that you believe has value? Even if there isn’t an official approval process required by the school, it’s good to have developed your rationale. This process allows you to have your defense at the ready should you need it. Sherman quipped, the rationale for a show is not, “I have a couple of senior girls who can pull this off.” Rather, the rationale includes the values found in the play that can provide its best defense. Ironically, it is the film of any given show (if it exists) that can be most detrimental to its eventual production. Sherman explained, “Often, people who make these decisions don’t know the difference between a script and a production. They look at Wikipedia or read a synopsis or watch a film of the musical; what they see in that movie is what they think you are going to do.” In preparing to mount a show, you need to be prepared to head off potential problems.

Sherman exemplified the problem by discussing the musical Sweeney Todd: “If an administrator were to watch the Tim Burton movie, they will see geysers of blood; when it’s on stage, I’ve never seen it with that much blood!” The key is to identify and talk through possible moments of controversy, or what Sherman refers to as “flashpoints” in the script. Howard reminded his listeners that they’re working with people who aren’t experienced in analyzing a script or producing a play. Teachers need to walk them through it.

• Develop dramaturgy so that it provides a thoughtful context for the play and find ways to share this information before the production.

• Build alliances and partnerships with community organizations that would be interested in the play’s message.

• Create a website where you include an article about the show’s significance.

• Share the message of the show with community members and administrators in a video; lay the groundwork. There’s no need for this video to be polished, but it does need to be sincere.

Sherman concluded the exercise by saying, “If someone decides they are going to get in a snit, they’re going to get into a snit. None of this guarantees that someone’s not going to object; but if you have done a lot of these things then you already have in place tools to create the content you need to defend your show.”

While Saturday’s workshop at the Teachers Institute emphasized the steps to take to try to prevent problems, Sherman did provide advice on what to do when you have a show canceled and how to support teachers who have had plays or musicals pulled from production.

“When this hits, the one person who usually can’t speak is the teacher,” Sherman explained. “Most teachers are not allowed to talk to the media without permission.”

For those who are reading about a show cancellation, there are ways to lend support:

• Reach out to the teacher and make sure that they feel supported; let them know that they are not alone.

• As long as it doesn’t put you at risk, share information about those in trouble; on social media the more you click “like,” the more the story spreads.

• Contribute to a GoFundMe that allows students to produce the show in another space.

Arts advocate Howard Sherman does this work because it’s important. He believes that there is a place for so-called family friendly shows in high schools, but that when students also engage with plays and musicals that contain important modern themes, it allows them to grow as people and as artists.

“It’s important to give students an array of theatrical experiences at a formative age,” Sherman said. “Students who want to pursue a career in theatre will find a way. What I want is for students to be exposed to a wide range of theatre and then become doctors, lawyers, engineers and programmers and go on to be our next audiences for all kinds of theatre.” SETC 2024 Teachers Institute ultimately provided teachers with rich ideas and tools to allow students to grow as they practice their art.

Howard Sherman’s dedication to assisting students and teachers was at the forefront of Saturday’s workshop. The plan was to work with teachers to prepare for the possibility of a show being censored in any phase of the production process. To get ahead of the problem, Sherman asked teachers to interrogate the scripts they plan to produce and emotionally able to handle the show, and you give them the ammunition they need.” Sherman went on to say that when one is preparing their materials in defense of a show, they should ask for help. For example, there’s a Facebook group, High School Theatre Directors and Teachers, that can provide useful information.

In addition to developing a rationale for a show, it is often important to get everyone on

However, there is something teachers can and should do. Let students know: “If you choose to speak about this, you must do it professionally and without anger. If you lash out and insult administrators or the school board, you prove their argument that you aren’t

by Steven H. Butler

The Suzanne M. Davis Memorial Award was created in memory of Suzie Davis, wife of Harry Davis, one of the founders of SETC and its 10th president. The award recognizes an individual who, over an extended number of years, has been outstanding in service to SETC. It is the highest award that SETC can bestow upon one of its own members.

When I think of the recipient of the 2024 Suzanne M. Davis Memorial Award, I cannot help but think of how Marci J. Duncan embodies all the good qualities of southern-ness and what it means to be an integral part of SETC. When I attended my first SETC event, it was in Chattanooga, TN and I had the honor to interact with three phenomenal people, Pearl Cleage, Ben Vereen, and Marci J. Duncan.

It was my first time at SETC and I attended the conference alone; however, when I met Marci, I immediately felt warmth and southern hospitality. All it took was a smile and hello, and the next thing I knew I was being schooled on what SETC was all about. Her personal

knowledge of SETC history was inspiring. It was then that I knew I had found my tribe and SETC became my new home. Time passed before our paths would cross again. This time, SETC had convened upon Greensboro, NC. I was even more impressed because this time Marci was expecting a child. However, she never missed a beat and poured forth the same beautiful warmth and southern hospitality. What impressed me the most was how she covered every square inch of that exhibit hall with gusto. Jokingly, I was convinced she was trying to walk that baby out of her.

When you see someone only once a year, sometimes it can be difficult to see how that person truly operates. In 2019, I began working closely with Marci and I was able to see that her beautiful warmth and hospitality was truly genuine. I also found out that she does not take kindly to ill intentions and when meeting them head on, she takes no prisoners. However, she always addresses tough situations with such grace and professionalism.

To me, Marci J. Duncan is a selfactualized person: a wife, a mother, a professor, an actor, a director, and a playwright. She has served on the SETC Board for over 10 years and is currently serving as the Auditions Coordinator for SETC Administration. She is also the Immediate Past President of the Florida Theatre Conference. She graduated from Florida A&M University and completed her M.F.A. degree at the University of Florida.

Marci J. Duncan is truly a “Super Woman” to me and many others. It is an honor to present the 2024 Suzanne M. Davis Memorial Award to Mrs. Marci J. Duncan. n

Dby Lauren Brooke Ellis

.W. Gregory (right) won the 2023 Charles M. Getchell New Play Award for her play A Thing of Beauty. Gregory is an award-winning writer whose plays frequently explore political issues through a personal lens and with a comedic twist. The New York Times called her “a playwright with a talent to enlighten and provoke” for her most produced work, Radium Girls which has received more than 1,800 productions in the U.S. and abroad. Other plays include Memoirs of a Forgotten Man, a National New Play Network rolling world premiere (Contemporary American Theater Festival, Shadowland Stages, and New Jersey Rep); Molumby’s Million (Iron Age Theatre), nominated for a Barrymore Award by Philadelphia Theatre Alliance; The Good Daughter and October 1962 (New Jersey Rep). The Yellow Stocking Play, a new musical comedy created with composer Steven M. Alper and lyricist Sarah Knapp, recently won Best Musical and Best Book of a Musical in CreateTheater’s New Play Festival on Theatre Row. The following is an interview with the playwright conducted by Lauren Brooke Ellis, SETC’s Chair of Playwriting.

D.W. Gregory is an award-winning writer whose plays frequently explore political issues through a personal lens and with a comedic twist. The New York Times called her “a playwright with a talent to enlighten and provoke” for her most produced work, Radium Girls, which has received more than 1,800 productions in the U.S. and abroad. More information at dwgregory.com

Lauren Brooke Ellis (LBE): Your award-winning work has been produced all over the world. Your stories strike universal chords that explore all sides of humanity and are suitable for any and all mediums. So ultimately, why did you choose the theatre?

D.W. Gregory (DWG): I remember vividly a production of 1776 that I saw with my mother at The Fulton Opera House when I was 17. “Mama Look Sharp” is one of the most moving songs in that play, and it brought her to tears — and she was not the kind to cry easily. I saw first-hand how this form of storytelling could trigger such a strong response — sometimes a passionate response — in its audiences. So I was always intrigued by it. And once I got into writing plays, it simply felt more natural to me than other forms. I had dabbled in poetry — I’m a terrible poet, by the way — and in short fiction. But those are solitary pursuits. The collaborative nature of theatre is that you are telling stories in a community setting; the community of the artists involved and the community created around the event. Why come together as an audience to see and hear

these stories? It is to share in that story-telling collectively.

LBE: What was your route to playwriting?

DWG: Indirect. At 18, I felt I couldn’t really go into theatre or study acting, which I wanted to do; I wasn’t encouraged to do that. [When I was living in Rochester] I saw that Writers & Books offered a workshop in playwriting, so I signed up. It was run by a retired theatre professor named Bruce Sweet, who was a great teacher and mentor, and he instilled everybody with this sense of, “You can do this. You haven’t done it yet, but you can do it.”

I stayed three years, and somewhere in this process, something clicked. I wrote a play for young audiences and I sent it off to a competition. It won — and the prize was a staged reading. And that was the turning point. If you’re used to writing narrative prose, [writing for the stage is] not intuitive at all. You have to be able to tell the story through active dialogue.

I made all of the classic mistakes new playwrights can make. The plays were flat, they weren’t dramatic, there wasn’t really

tension, it was just people talking. But after a couple of years, I stumbled onto a good story and suddenly had a play that worked. Winning that competition, for me, was a signal that said, “Okay, I’m on the right track.”

LBE: Was it hard for you to claim the title of “playwright”?

DWG: It was hard at first, starting to think of myself as a playwright… It’s funny. When I was still living in Rochester, one of the community theatres sponsored a play contest and I entered a script. They picked three plays to perform, and it caused a little bit of a stink that all the plays were written by men. A few actresses came up to me after the performance to tell me how offended they were that my play hadn’t been chosen, even though they had lobbied hard for it. It was stunning to me that someone was passionate enough about a play of mine that they wanted to advocate for it. It took me a long time to get to where I had enough confidence to be my own advocate. Early on, I could be talked out of things. I thought everyone else knew more than I did.

LBE: I think that lack of confidence is something early-career artists of all mediums experience. If you were going to give a young artist some concrete steps to take to make a life or career in the arts, what are three things you would tell them to do?

DWG: Well I think the first order of business for anybody, whatever you’re doing, whether you’re a photographer, a playwright, a painter, dancer, or performer is to perfect your craft. Playwriting is a craft. When I go to see a play, I want to feel like I’m in the hands of a really skilled craftsperson who knows what they’re doing. It’s not slapdash or arbitrary. So you have to invest in your craft, and that means investing in yourself. That means giving yourself the time to develop. Then you have to learn the business, and then you have to figure out where you want to work and how to connect with people who will be able to help you move your work forward. But it’s not just about them being in a position to help you, but figuring out what you have to offer them… But all theatres have the same issue — they’re looking for plays that are going to be of interest to their audiences. And those audiences vary from one theatre to the next. It’s not homogenous. So, it’s on you as a writer to get to know these performing arts organizations and the audiences they serve.

LBE: I think it’s so interesting to talk about audiences and what kinds of seasons are being made right now. Since 2020, theatres have faced such a huge upheaval. First with the pandemic and then with the reckonings happening around the lack of equity and inclusion. Your work has always seemed to address these issues. So my question is, how are these shifts in conversations landing on you as a playwright?

DWG: I don’t know if I can say exactly. I don’t think of my work necessarily as “feminist” — because “feminism” has an undeserved connotation of being strident. But I have been wrestling with power relationships between men and women, and it’s a recurring theme in a lot of my plays. A lot of them are about