8 minute read

The Return Of The Black Parade

from The Brag #748

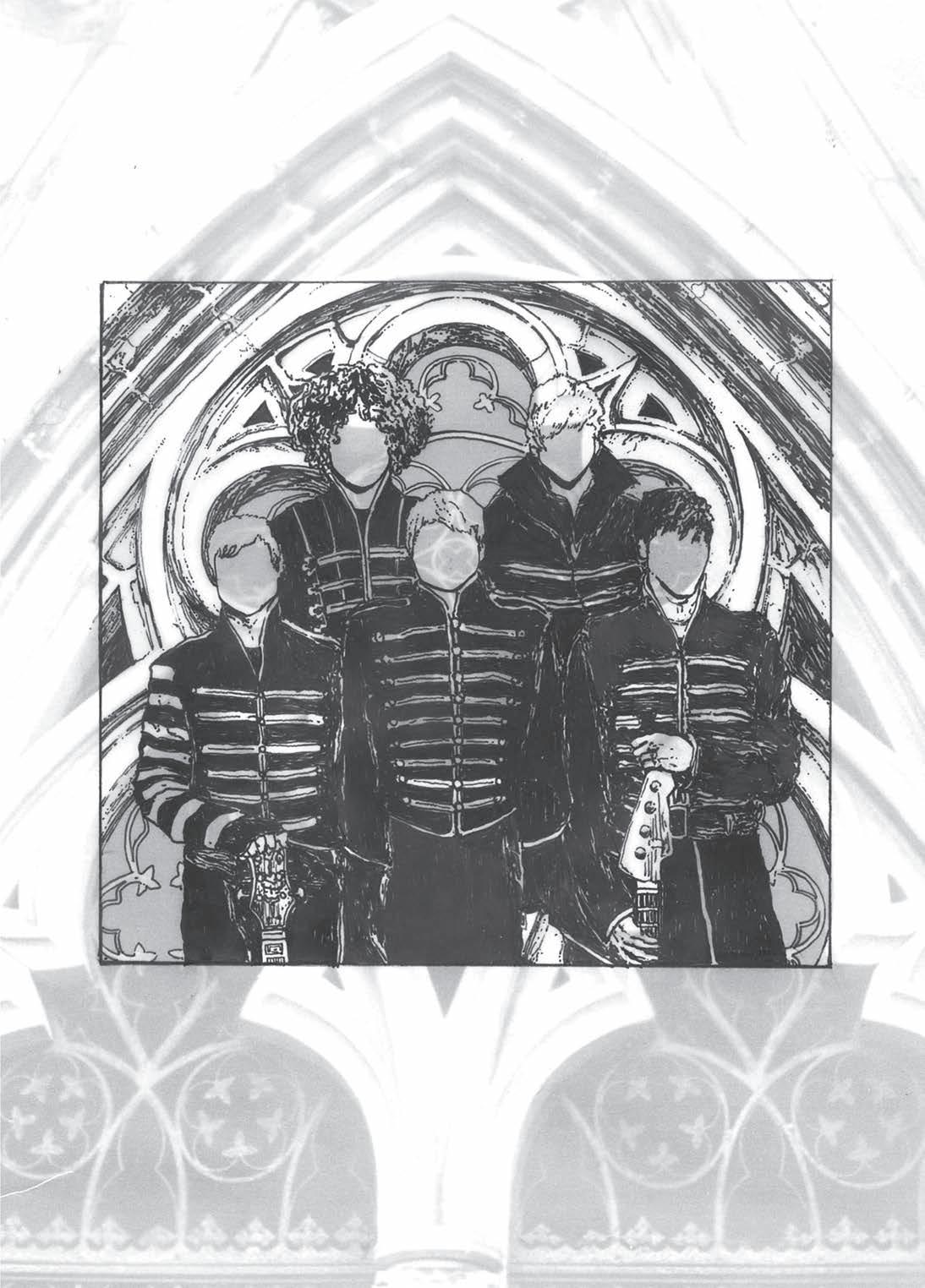

Illustration by Connor Xia

The Return Of The Black Parade

Advertisement

Elizabeth Green explores the legacy of My Chemical Romance, from leading fans out of the depths of depression, to the days when parental hysteria would label the group as a suicide cult.

Once the voice for all the broken souls across the globe, My Chemical Romance’s departure from the music scene in 2013 devastated their hundreds of thousands of fans. They were left to carry on with only their music and the mistake of overly bleached hair. But it’s time to get your eyeliner on standby because the blistering intensity of My Chemical Romance is back. Gerard Way, Frank Iero, Mikey Way and Ray Toro are booked to do a string of shows, including two in Sydney and Melbourne. The six years of distance between the danger days of a united MCR haven’t diminished fan’s love for their raw theatricality.

Their first reunion show, simply titled Return, sold out within minutes, and fans worldwide have kicked up a hell-storm and a new appetite for that irresistible fervency that’s been missing from the music scene. Their fan base has only grown in their absence, with waves of younger listeners latching onto the addictive riffs and jarring truths found in each song. Killjoys, it’s time to make some noise again.

The band’s forceful hooks and emotive lyrics were the catalysts for so much youthful angst from the 2000s onwards. With each song, Way’s gale-force voice barrels at you like a high-speed train, and you have no choice but to jump on his wavelength. Subtlety isn’t the name of the game when it comes to MCR, but if you needed a punch to the gut in the form of emotional vulnerability, these are your guys. That’s the thing about ‘emo’ music, you’re under a barrage of noise that echoes what’s inside of you, and MCR isn’t afraid to leave you choking on line after line of raw emotion. MCR was able to not only last beyond their breakup, but they’ve also been able to reach out to new listeners. It was their ability to tap into the rage, fear and sadness universal to everyone who queues ‘Helena’ on Spotify which made them iconic.

The width of MCR’s fan base is undeniable, but the specificity of their appeal to younger audiences through music video after music video has allowed them to play a part in shaping the minds of an upcoming generation. Fans will recall what it was like to play a song and have whatever pent up feelings they had thrown back at them in a way that is addictively jarring.

I spoke to fans Krystal Docker and Franni Kuan, who stanned MCR hard back in the day, to speak about what it was precisely about this band that their hearts clung to so earnestly.

“At the time, it just felt truthful in a way that no other music had felt. It was very affirming at the time to hear music that really, accurately reflected how I felt,” Docker told me.

For each person lost in the fog of their traumatic teen years, songs which appeal to the emotional and theatrical allow them to step into their feelings. Each generation needs music to soundtrack their coming of age - whether or not they are in a dark place, yelling that “No one understands” them before slamming their bedroom door. Songs like ‘Disenchanted’ spoke out for younger audiences, with lyrics like “I spent my high school career, spit on and shoved to agree,” calling out society’s inclination to force young people to fi t the mould. Speaking to Kerrang about their rompy, feverish hit ‘Teenagers’, Gerard Way said that it was “…a commentary on kids being viewed as meat; by the government and by society.”

of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, MCR never wanted to be a preaching band. Like their listeners, the members of the band were themselves ‘not okay’. Way has especially been open about his struggles with suicidal thoughts, depression and substance abuse, both before and during the band’s height. There’s not a ‘hush-hush’ attitude towards the severity of these struggles either. The band’s live album-cum-documentary Life on the Murder Scene reveals Way’s battle with alcoholism and drug use and shows footage of his excessive drinking and substance abuse. The videos include interviews discussing Way’s suicidal intentions, with their band manager from 2005 to 2009 revealing how he had to “talk him down” from committing suicide.

Thatʼs the thing about ʻemoʼ music, youʼre under a barrag e of noise that echoes whatʼs inside of you, and MCR isnʼt afraid to leave you choking on line after line of raw emotion twice.” Though Way once described creating an album as “surgery without an anaesthetic”, he also revealed that in creating music:

You only have to look at the comment section of any of their music videos to find scores of fans who say that their music saved them. There’s even a book on MCR titled My Chemical Romance: This Band Will Save Your Life. Way doesn’t just tap into the misery that his fans are going through, he’s in the trenches with them. Their music emphasises and commemorates the feelings of each listener who’s going through hell. Each song beats directly out of the band’s own struggles, speaking with candour to the loneliness and heartbreak of the listener in rabid echoes.

It’s the openness to discuss mental ill-health and suicide that has influenced a generation of young people.

“They spread a very hard-hitting sort of message at the time. It was that ‘It’s okay to feel shitty,’ because you’re not the only one. It’s okay to not be okay,” Kuan said.

Out of the trust Way develops with his audience, he provokes them to speak out about their struggles and to try to get better. During one performance, Way directly calls fans to open up and speak about their issues.

“If you, or someone you know, are severely depressed, you need to fucking talk to somebody. Your best friend, your mom, somebody at school, I don’t give a fuck. Because pissing your life away on suicide is fucking bullshit,” he said.

For many fans, there is a darker side to conflating your band’s identity so closely with mental illness. If you’re feeling sad, broody music can help you reach catharsis or to work through inner turmoil. However, evidence shows that for people who have depression, listening to sad music like MCR’s can exacerbate feelings of helplessness and lead to spirals of rumination. This is something that Docker agreed with, and she says that widespread self-harm amongst MCR fans normalised that behaviour.

“I think it can actually contribute to getting stuck in a rut. I think sometimes their music might have made me even more depressed… a lot of my friends and I made our depressive illness a part of our identities, and that’s a really dangerous way to define yourself,” she said.

The band has been criticised for being a ‘suicide cult’ by news outlets such as the Daily Mail, which blamed MCR for the death of a thirteen year-old girl. Despite the Daily Mail’s less than perfect reputation, parental hysteria ensued.

But for Kuan and many other fans, they were able to discover a support group in the form of the My Chemical Romance fandom.

“I found, not so much that MCR themselves and their music helped, but I found huge comfort in their fandom and their community. Everyone was talking about mental health online,” she said. Dr Rosemary Lucy Hill, a lecturer in Sociology at the University of Leeds and author of the research paper ‘Emo Saved My Life’, argues that My Chemical Romance challenged the discourse surrounding mental health. She also claimed that gender is a significant contributing factor to how the media framed MCR.

“We need to listen to what young women have to say... Rather than emo being a fashion that pushes them towards the feelings of desperation, into self-harming, to commit suicide, it can help fans to survive mental ill health,” Hill writes.

Hill does acknowledge that for some fans, the music may be more of a hindrance than helpful. Still, within her research, she found that the band helped them overcome unhappiness, or to deal with bullying or long-term illness. Despite the focus on mortality and heartbreak within many of their songs, the ones that are remembered are the ones about carrying on despite whatever challenges you’re facing.

“I am not afraid to keep on living / I am not afraid to walk this world alone ... / Nothing you say can stop me going home”, Way belts out on the track ‘Famous Last Words’. The defiance and unabashed rebellion of My Chemical Romance’s songs drive listeners to the centre of their feelings, then offers them a way out. For a generation that has led the way in opening conversations about mental health, rebelling against stigma and silence is exactly what they needed. ■