12 minute read

Coiled Tubing Drilling Offers Rising Opportunities for Oil

Coiled Tubing Drilling Offers Rising Opportunities for Oil and Gas Recovery Worldwide

By: Ikenna Idam, LWD InTouch Engineer, Schlumberger Oilfield Services USA

Advertisement

In 2019, the Coiled Tubing Drilling (CTD) market was valued at more than $3 billion, with well intervention services accounting for more than 60% of the market in North America and Europe. In the Middle East and Africa, oil and gas companies are investing in well intervention to increase production in mature or previously depleted oil fields, creating new opportunities for CTD expansion and resource extraction. While Russia has been slower to adopt CTD technology, its use there has risen steadily over the last decade. And in the Asia Pacific region and Latin America, growing populations combined with a government focus on reducing import dependency is hastening the demand for enhanced oil and gas recovery, driving further investment in CTD solutions to boost well production. As opportunities continue to rise worldwide, CTD is expected to grow to $4 billion by 2026, making it one of the fastest-growing segments in the oil and gas industry.

Since its introduction in the mid-1960s, coiled tubing has been used for increasingly diverse applications in oil and gas exploration and drilling operations for energy and other resource by-products. The tubing is made from an alloy of carbon steel sheet or composite fiber materials, generally with diameters of 1 to 3.25 inches to fit into existing wellbores, and able to withstand downhole pressures of up to 130,000 PSI.

The advent of more advanced CTD techniques in the early 1990s created new, costeffective solutions for well intervention services, enabling operators to tackle many of the challenges that affect oil and gas wells and deplete production over time, such as fluctuations in well production and injection pressure. Over the last two decades, CTD has proven to be a reliable and less expensive methodology (as compared to conventional wireline processes) for rock fracturing, production tubing, wellbore cleaning, sand control, cementing, tube logging and perforation, nitrogen kickoff, acidizing stimulation and other applications, and new uses for coiled tubing are developing daily.

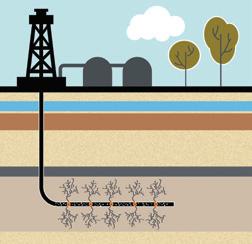

How it works

The primary elements of a CTD operation unit consist of the four modules: 1. Reel: whether it is manufactured from a continuous carbon steel alloy sheet or special composite materials, the tubing can be over 25,000 feet long and is typically supplied on a reel spool that can weigh up to 24 tons; rolling the tubing around the reel maintains tubing flexibility during storage and transportation. 2. Control Cabin: the unit where personnel control and monitor all coiled tubing operations. 3. Injector Head: provides the force required to drive the coiled tubing string downhole and retrieve it upon completion of the operations. 4. Power Pack: generates the power required to run the coiled tubing unit as either hydraulic or pneumatic.

Oil and gas operators are regularly turning to CTD to take advantage of its many operational and economic benefits. In general, coiled tubing optimizes drilling across a wider array of well conditions and is a better option for horizontal wells. Coiled tubing operations yield higher levels of producibility, performance, well control, and safety, and shorter times to mobilize. While all those factors influence the economics of drilling operations, perhaps the most significant gains come from the absence of a Workover Rig, which is not required for CTD, thereby eliminating associated rig costs. In addition, the possibility to operate within the limits of the well pressure, without the need to kill the well, helps avoid formation damage and reduces the “trip in” and “trip out” time when compared to conventional drilling.

The various applications of CTD technology are typically categorized under two broad headers: Coiled Tubing Workover and Coiled Tubing Drilling.

Coiled Tubing Workover

Coiled Tubing Workover (CTW) is a form of intervention activity in an existing oil well, performed when a producing well is seen to be negatively affected in productivity, and thus invariably causing a drop in revenue generated by the well. The problem may be due to an increase in the injection pressure or changes in the production characteristics, among other reasons, but the condition essentially triggers the need to improve the conditions of the well in order to bring it back to optimum production.

In these cases, coiled tubing is an excellent and cost-effective solution. As there is no need to kill the well (unlike in conventional drilling), the coiled tubing is deployed in the wellbore by inserting it through the existing wellhead. This technique saves time and resources by enabling a “cleanout” activity, such as removing sand or filling from the wellbore, retrieving a failed mechanical tool, or a perforation activity. The procedure involves injecting fluid, which is applied at a fluid velocity (determined by modeling) and operating the fluid flow at an optimum velocity to avoid abrasive damage to the tubing. During this process, the fill or sand materials that have formed in the wellbore are broken up and dispersed, and the dispersed fluid is then circulated to the surface.

In cases where the well has developed a high hydrostatic pressure, resulting in the inability of the reservoir fluid to flow, nitrogen is used to improve the well production. The circulation of nitrogen helps lift the borehole fluids, enabling the reservoir fluid to resume flow through the wellbore.

Coiled Tubing with the four modules of Coiled Tubing Drilling equipment.

Coiled Tubing Drilling

CTD uses coiled tubing equipment to reenter non-producing wells to drill into the new reservoir targets. In this application, the bottom hole assembly (BHA) size is usually closer to the borehole size. Since the pipe is not rotated (unlike in conventional drilling), the direction or trajectory of the borehole is controlled with the aid of an orienting device which rotates a bent housing attached to the coiled tubing equipment to a desired orientation (the “toolface”).

The advances in CTD over the last 20 years allow for real-time downhole measurements which can be used for the wellbore treatment, Measurement While Drilling (MWD), and Logging While Drilling (LWD) operations. Using CTD, operators can make critical measurements including wellbore inclination and azimuth, toolface orientation, formation gamma ray, shock load measurements, wellbore pressure, weight-on-bit, and casing collar locator, among others. CTD also eliminates the conventional drilling requirements for drill pipe make-up, or screwing drill pipes together, which typically affects the pressure equilibrium and reduces drilling time by 30-50% as compared to conventional jointed pipe drilling.

CTD applications are also suitable for Under-Balanced Drilling (UBD), which allows the well to continue to produce while the drilling operation is ongoing. In some cases, based on production levels from a reservoir, Under-Balanced Drilling could be replaced by Managed Pressure Drilling (MPD), a method employed when the CTD equipment is unable to cope with the volume produced. In practice, this is not a challenge because operational adjustments can be made to switch between UBD and MPD techniques. The decision to adjust between UBD and MPD is aided by an electrical control line which runs through the center of the coiled tubing and enables real-time recording of pressure changes in the well (downhole), which is immediately transmitted to the surface (uphole) for operational adjustments to be made, ensuring safe operations.

Oilfield services companies around the world are choosing CTD over conventional drilling to achieve additional advantages, including faster “tripping” time and rigup/rigdown time, less weight-on-bit, and reductions in personnel and environmental impact associated with fewer cleanup activities. Proven time and again, these benefits translate to a smaller footprint with higher revenue for the operator, leading more operators to embrace and expand the opportunities for CTD market growth in coming years.

About the author: Ikenna Idam is an LWD InTouch Engineer at Schlumberger Oilfield Services, where he has served for 20 years in Nigeria, Brazil, and the USA. Now based at the Schlumberger Technology Center in Houston, Texas, Mr. Idam specializes in the design, implementation, testing, and maintenance of hightechnology Logging While Drilling (LWD) tools and techniques and related resistivity and nuclear equipment management, and manages technology-based interactions with Schlumberger’s global field locations.

Be Wary of Government “Help”: We Cannot Let Negative Prices Lead to Negative Policies

By: Kenny Stein, Director of Policy, Institute for Energy Research

The world is awash in crude oil from the only-recently paused price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia. That supply glut has been combined with a massive demand drop as economies around the world have been shut in and shut down to battle the global pandemic. Storage has been able to absorb U.S. production so far, anticipating demand rebound later this year — but there is only so much storage. As it fills up, U.S. producers will be forced to further slow the pace of their production, hitting their bottom lines, and leading to layoffs among the millions of jobs directly and indirectly tied to the industry.

But while the industry has its head down trying to survive this crisis, the green vultures leading the Keep it in the Ground movement are circling, ready to strike. They see this as their opportunity to deliver a killer blow to the domestic oil and gas industry.

Anti-energy leftist Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (DN.Y) tweeted how much she loved seeing the May WTI oil futures price go negative, seeing the crisis as an opening for her Green New Deal. Other environmentalists are demanding green subsidies be included in future government relief bills or for energy companies to be prevented from accessing existing relief programs.

As difficult as things seem, the supply glut and coronavirus demand destruction are short-term factors. While negative futures prices are unprecedented, the reality is that this is a sign that the markets are working as intended. Adjustments in investment and production were already underway, these negative prices are telling market participants to speed up the pace of their adjustments.

The worst thing the oil and gas industry could do is let panic and crisis lead to bad policy. This short-term shock cannot be a justification for abandoning competitiveness or the free-market policies that created America’s domestic oil and gas production boom in the first place.

These are extraordinary and unprecedented times for the oil patch.

Too many of the policy responses thrown out have smacked of central planning: government-mandated production cuts, tariffs on imports, preventing ships from unloading imported oil, paying producers not to produce. These are precisely the wrong responses.

Government interventions inevitably prop up weaker players at the expense of stronger ones. Companies with wells that are cheaper to produce, be it from geology or technology, or with better hedges against lower oil prices, or who have better cash or debt balances should be allowed to reap the rewards of their planning. Government mandates eliminate the benefits of these distinctions. Those with the best lobbyists win, not the best business practices.

Then there is the matter of government competency. How many operators are willing to trust bureaucrats to manage this industry? The proposals under discussion assume that government management will somehow produce price stability. But bureaucrats in Washington or state capitals are not all-knowing or all-powerful, as long experience shows. There is no universe in which replacing the judgment of markets with the judgment of bureaucrats will be better for the oil and gas industry.

But it is not just that putting the industry under the direction of government would fail to fix the current crisis. Once the government is charged with managing the price and supply of the oil and gas industry, it will never relinquish that power. I assure you, anti-energy greens, waiting for a friendlier future administration, will take those powers and pursue even greater government interventions like taxing carbon dioxide emissions or banning hydraulic fracturing.

This is not just theoretical musing. It should be instructive that during the Texas Railroad Commission hearing on potential proration of oil production, a raft of environmentalist groups including the Sierra Club and the NRDC lined up in favor of government intervention. Anytime an oil and gas company finds themselves on the same side as the green extremists, it should give pause. We must always remember that everything these organizations do is with an eye towards the very elimination of the oil and gas industry.

There are certainly things that the government could do to help soften the devastation of this crisis. Renting storage space in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, relaxing regulations that impede conversions of new storage and pipelines, waiving steel tariffs that increase the cost of drilling and transportation, and waiving the Jones Act, which raises the cost of moving oil around the U.S., would all be welcome policy actions. Importantly, these would be positive actions in their own right, independent of the short-term crisis.

U.S. producers will rein in production in the near term, and that adjustment will be difficult, but demand will eventually return. Attempting to centrally plan this adjustment will mean worse short term outcomes while weakening the industry long term. We must have the humility to recognize that this historic confluence of factors cannot be fixed by government regulation.

Oil is not valueless; it is still the commodity that powers the world and the feedstock for most products we use every day. What we saw clearly during the last oil price drop in 2015-2016 is that American producers are champion innovators. In response to low oil prices, shale operators figured out cheaper and more efficient ways of developing shale wells. What is needed now is more of that kind of ingenuity, and that doesn’t come from government.

When the economy rebounds, oil will rebound. The ultimate solution for the oil industry is getting the economy back open and running again. We have seen hopeful signs in recent weeks, as some states and countries have begun partial re-openings.

A dynamic, innovative and flexible oil industry will best be able to rebound when demand returns. A coddled, subsidized industry with the government trying to artificially prop up prices will wither, leaving it easy prey for a future administration that wants to use its power not to help, but to destroy.

About the author: Kenny Stein is the Director of Policy for the Institute for Energy Research. A Texas native, he worked for U.S. Senator Ted Cruz as Legislative Counsel covering energy, environment and agriculture issues, and as Policy Advisor for the Cruz presidential campaign. Stein has past experience in political roles on national and state campaigns and additional policy roles with free market organizations like Freedomworks and the American Legislative Exchange Council. He received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Houston and his B.A. in International Relations from American University.

SAFE IN THE FIELD. SAFE AT PLAY.