4 minute read

Milwaukee Art Museum Reopens

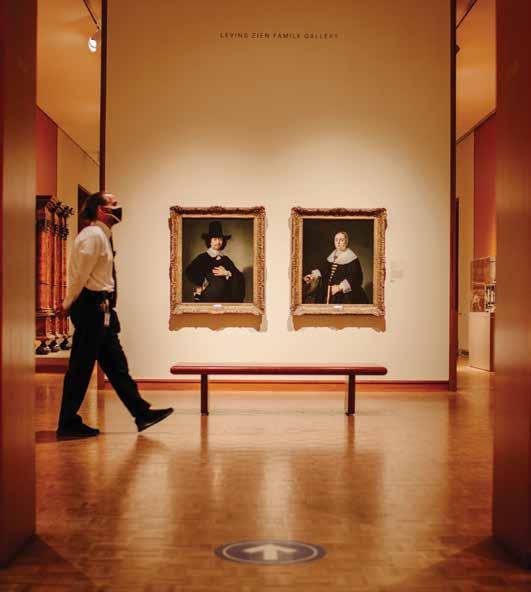

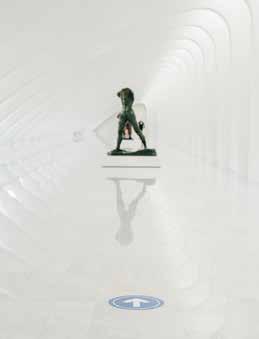

The Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) reopened to visitors last month, albeit in an abridged form. Visitors are required to reserve a ticket in advance online and to adhere to a posted code of conduct requiring social distancing, mask wearing and restricted movement through the galleries. One might think this would diminish the experience; however, while it does pose obvious limitations, it encouraged me to deviate from my own natural viewing patterns enough to see the collections from a different point of view.

In the late 1960s, the Marxist agitprop artist Guy Debord professed that artists should encourage the pursuit of alternative pathways through the commercialized terrain of the modern world. These dérives, as he called them, were meant to destabilize conventional engagements with public

Advertisement

space—like a cultural detour of sorts, which is what I inadvertently did at MAM by viewing the abbreviated collection from a totally new vantage point and mental state. Simply entering from the West, through the classical galleries, past the early Renaissance altarpieces and Christian devotional art, reoriented my expectations before I had a chance to solidify them. I’m ashamed to say that I rarely step into a museum with chronological ambitions, and it was good to be forced back onto the foundations of art history.

A little reordering of one’s perspective, externally driven or not, can be a gift. I haven’t gazed into a high Northern-baroque morality painting with such dedication since Marilyn Stokstad’s slide-lit, endurance test of a class on the subject 25 years ago. But during my visit to MAM, I disappeared into Matthias Stom’s Christ Before the High Priest with a rediscovered reverence. Those wooly lectures came back to me in a wave of humble, bittersweet nostalgia: dramatic light sourcing, Reformation and Counter-Reformation subtexts, Walloons and Flemings. All of it telling me about the potential of culture to create and propagate symbols of virtue within a given society. Like facemasks, for instance.

ART HISTORY WITH FRESH EYES

I carried my enthusiasm through the rest of the galleries, following art history with fresh eyes. The roped off Rococo interior with its Regency furniture and courtly paintings looked newer and more relevant amidst our own gilded age, itself flirting with revolt. That frilly Fragonard at the center of the room connected me improbably to the nearby Frank Stella in the contemporary galleries. Their confectionary colors hit the same notes, where their formal and conceptual missions diverged almost contemptuously. The two treasures spoke volumes about various accounts of cultural prestige. One about excess, the other about control; one of martial virtues, feudal traditions, and another about a modern American restraint and sublimated desire. Both in the same museum, 200 years, 100 feet and a simple reorientation of the mind apart. My trip through art history progressed on top of floor arrows through the gallery of 20th century design, where the largely intact gallery features everything from chairs to teapots to jukeboxes. The practical nature of the works on display marks the complicated intersection of art, culture, taste, technology and, finally, what we end up considering as historically relevant. A scale by Dieter Rams, a bookshelf by Ettore Sottsass and a chair by Gerrit Rietveld all lived once as radical visions of modernity, before their spirits were reappropriated into the realms of popular taste and mass production. The

connection of design to our national sport of shopping gripped me this time more than it had prior. The final few arrows led past a Light-and-Space wall sculpture by Craig Kauffman that lost some of its metaphorical shine. I considered how, five decades ago, the iridescent untitled lozenge stood as a bold pronouncement of post-industrial majesty and material might, and though I’ve always appreciated his work, I couldn’t avoid thinking about it at that moment as plastic first and material transformation second.

Our lives are deeply immersed in the invisible shapeshifting plasma of history. We usually don’t get to see its form, except in rare occasions when the historical machine is accidentally compromised and stops for a moment. Like, say, in a pandemic. My trip to MAM reminded me that beyond that seemingly perpetual and monolithic narrative pathway lies countless alternatives. It’s comforting, if of the cold sort, to be reminded that history is a reflection of us, but it is also made by us and can thus be taken and remade as we please, as long as we care enough to take the right detours off the institutional highway.

Shane McAdams is an artist whose work has been exhibited in New York, Portland and elsewhere. He has written for The Daily Beast and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and was an adjunct professor at Rhode Island School of Design and the Pratt Institute.