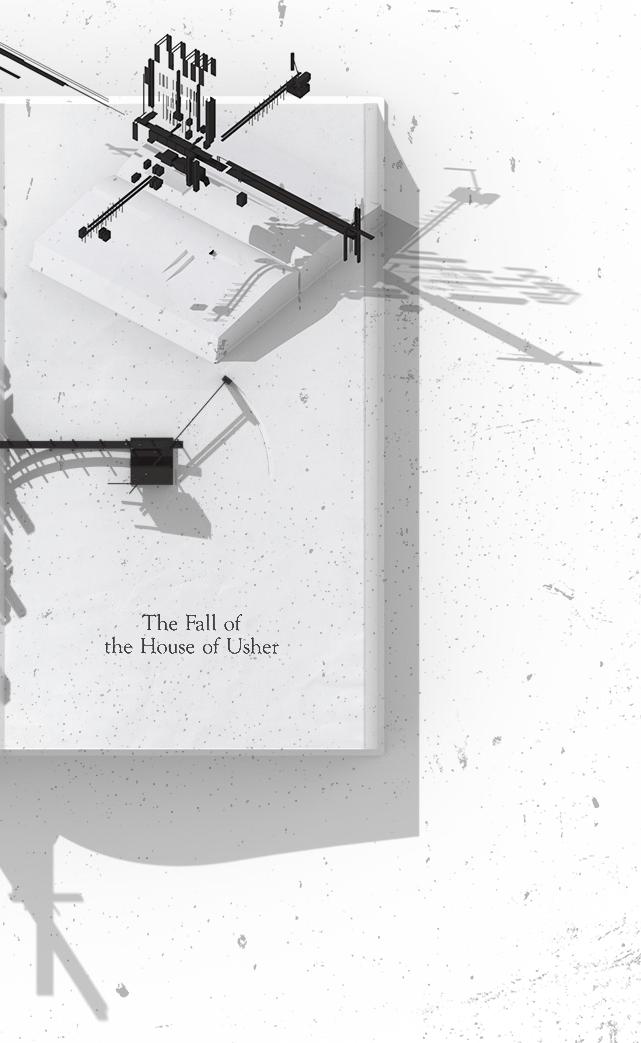

A thesis by Nicholas Sinclair

by

Nicholas Sinclair

A 120-point thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfi llment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture (Professional)

Victoria University of Wellington Wellington School of Architecture

2023

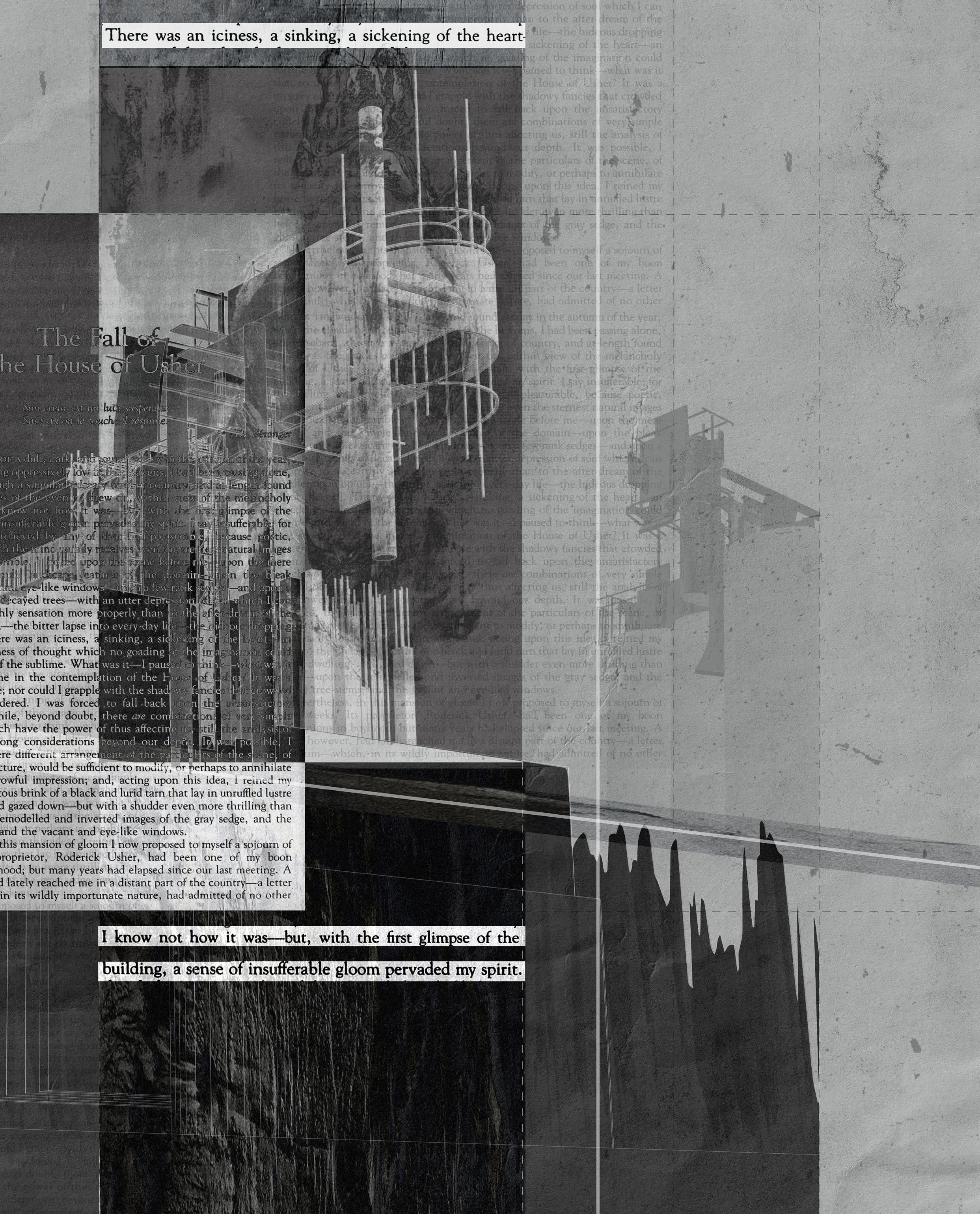

During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher.

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Fall of the House of Usher

We live in a world that has access to a multiplicity of devices and means of communication with the outside world. Despite being more connected than ever, one can still find oneself alienated from society, whether it be through perceived difference, pandemic, ostracisation, or any number of other reasons. With this supposed limitless connection, perceived security can develop on just how connected we are. Therefore, it is even more prudent a time than ever to address the individual’s alienation from society.

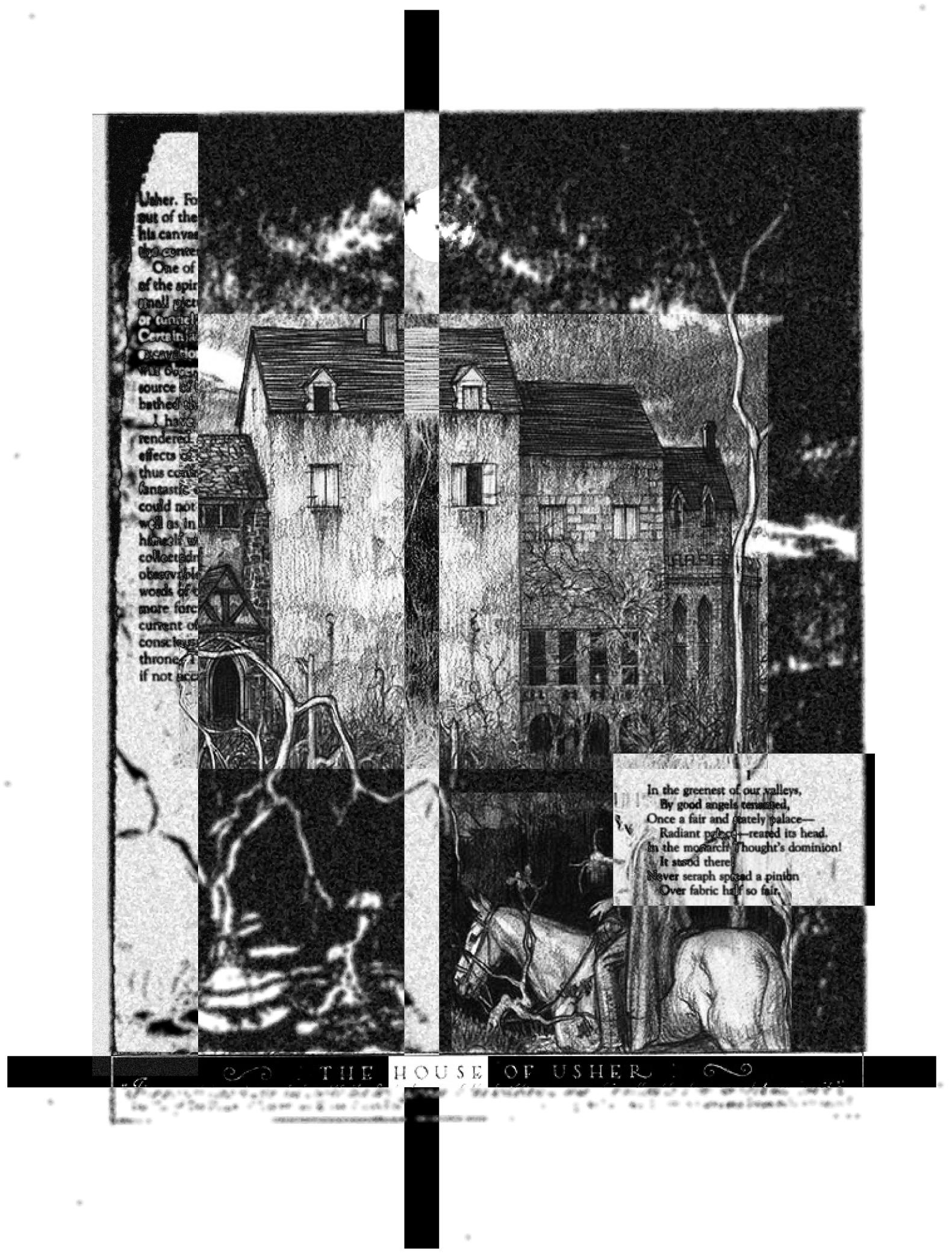

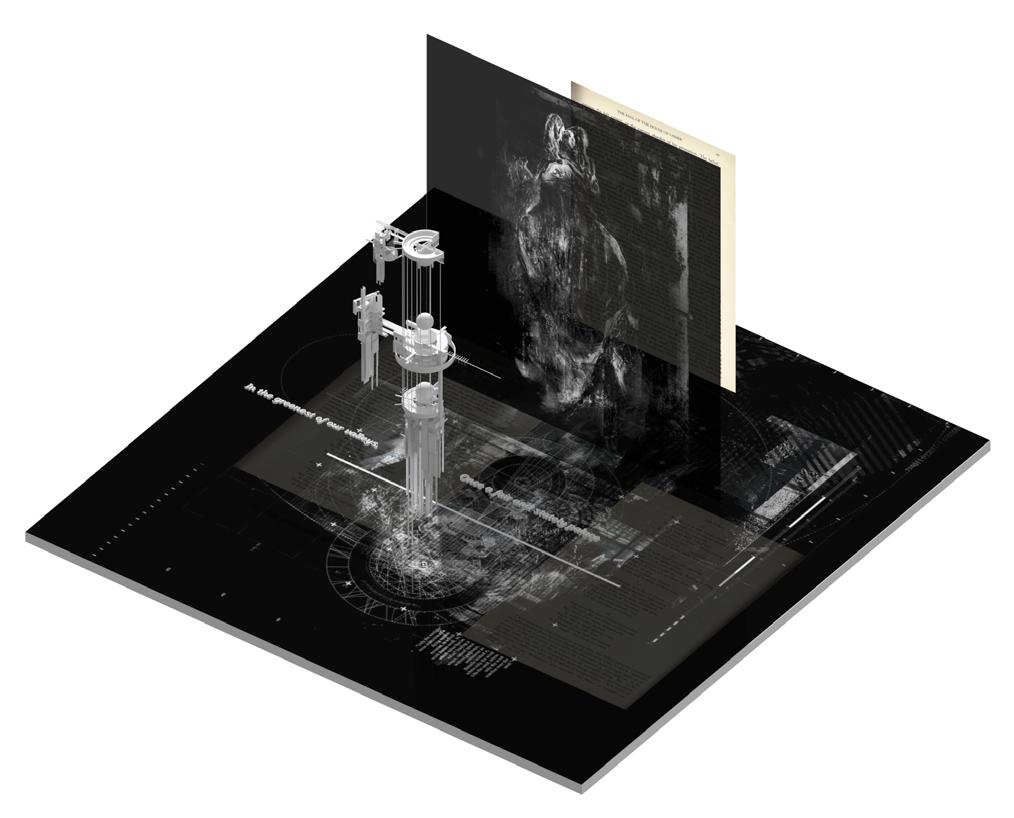

This thesis uses Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) as a literary provocateur for the design of an allegorical architectural project. In his story Poe uses architecture, the Usher house, as an allegorical device to convey the theme of alienation from society, and the dangerous ramifications it brings for an individual. This thesis investigation seeks to re-present this theme from Poe’s short story as a work of architecture.

Penelope Haralambidou describes the allegorical architectural project as a critical method for architectural design research; it draws from design disciplines outside the field of architecture to inform new ideas about architectural design. While Poe’s short story reflects primarily on the characters who inhabit the house, this architectural research thesis reflects primarily on the allegorical library and the books that are its ‘inhabitants’, and then finally the library as an ‘inhabitant’ of the house.

The principal aim of this research thesis is to investigate how an allegorical architectural project can be used as a critical method to enhance understanding of alienation and the individual’s connection with the outside world, or lack of. This will be addressed by transposing and architecturalising three of Poe’s primary themes within The Fall of the House of Usher; Artifacts, Dialectic Dialogues, and Temporality.

To fully explore the possibilities of the allegorical architecture project, the context of this research exists within a purely speculative realm and aligns with Haralambidou’s methodology. Although there is no intended physical site, to make the outcomes more convincing to the viewer experiments are explored in such a way that they could exist. The implication of this research is not to solve the difficult issue of the alienated individual, but rather to facilitate self-reflection so that one may understand their connection with the wider world, while simultaneously providing a method of conceiving a house that otherwise could not exist.

This design-led research investigation asks: how can an allegorical architectural project be used as a critical method for the design of a ‘house’, that enhances an awareness of the alienated individual?

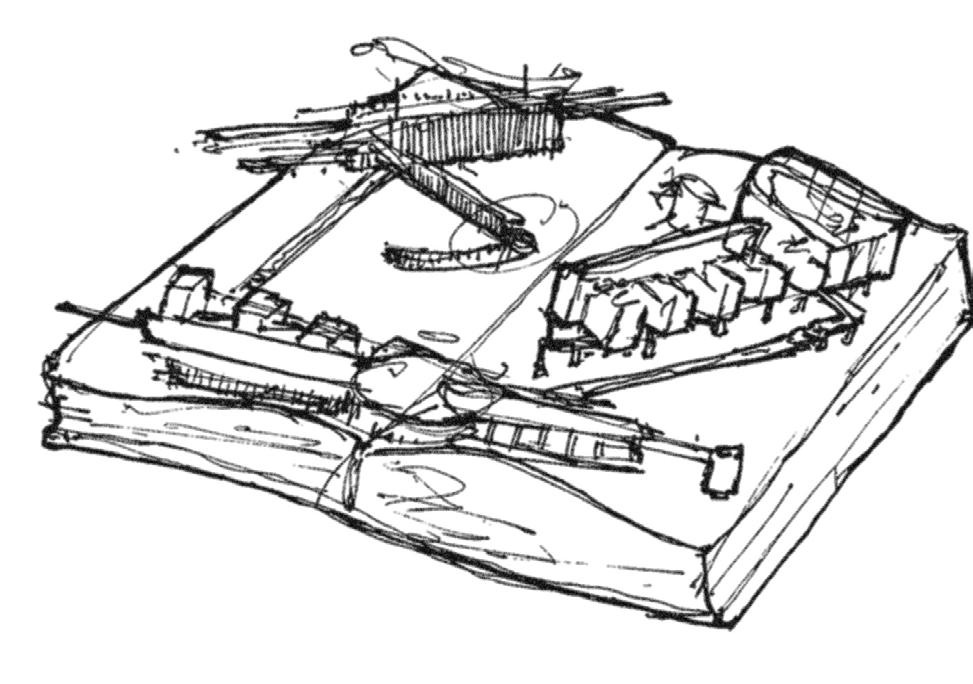

Fig. 0.3

Author enjoying a book, 2000.

Literature brings us to the brink of existence. Its imaginary landscapes invite the reader to be a voyager filled with wonder, but the prospect of the marvellous that dazzles the eye may also open on to a dark world of terror and despair.

- Anna Smith, Julia Kristeva Readings of Exile and Estrangement

For as long as I can remember I have loved delving into any type of media that has an air of mystery and ambiguity to it and ultimately requires one to understand. From a book detailing how a factory works, to reading my mum’s medical encyclopaedias, to the cliche murder mystery, I would soak it all in.

I owe the foundation of this thesis to two people. First and foremost, Daniel my supervisor for infusing the realm of architecture I know with the concept of narrative and allegory, to which I would otherwise be oblivious. I was first introduced to this in my third year of studies, only to build upon it in my fourth year, finally resulting in this thesis which is the culmination of multiple years of delving further and further into a subject that brings me constant joy and satisfaction. This method of designing has allowed me to infuse my designs with stories and meanings that would otherwise be missing.

Secondly, my friend, flatmate, and classmate Chris. At the beginning of 2022, we were unassumingly discussing our passions for literature and the poetic allegory, to which he suggested I read Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. Little did I know that this suggestion would ultimately transpire into a year's research. I could not be happier to have received that one suggestion that led me down the path I have gone down.

Literature has an amazing ability to affect its reader; as Anna Smith’s quote aptly states, it allows the reader to become a voyager into countless possibilities from wonder to terror. Delving into Chris’ suggestion resulted in exactly this, promoting thoughts, questions and ponderings on the mystery and meaning of the story. Beginning to remove the veil on these questions led to the discovery of a vast and varied set of readings of The Fall of The House of Usher, most falling into the category of allegorical. Furthermore, the story relied heavily on architecture to convey its themes. And I was sold; a long-standing passion for the allegorical and architecture met. Thus, the idea for this thesis was born.

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Poetic Principle “

I would define, in brief, the Poetry of words as The Rhythmical Creation of Beauty.

To my supervisor Daniel for all the engaging discussions that founded and continued to drive my passion in the field of architecture; including the sometimes stern ones that kept me on track. I undoubtedly would not be where I am now without your mentorship.

To my friends Christopher and Sofia for the countless coffees, chats and discussions that fuelled my drive and provided relief throughout the completion of this thesis.

More than anything I want to thank my mother whose undying support has made this rollercoaster of a degree possible. Thank you for always being a sounding board for my tangents and digressions, a source of wisdom and a fantastic mum.

1.0 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Problem Statement

1.3 Research Proposition

1.4 Research Question

1.5 Research Aim & Objectives

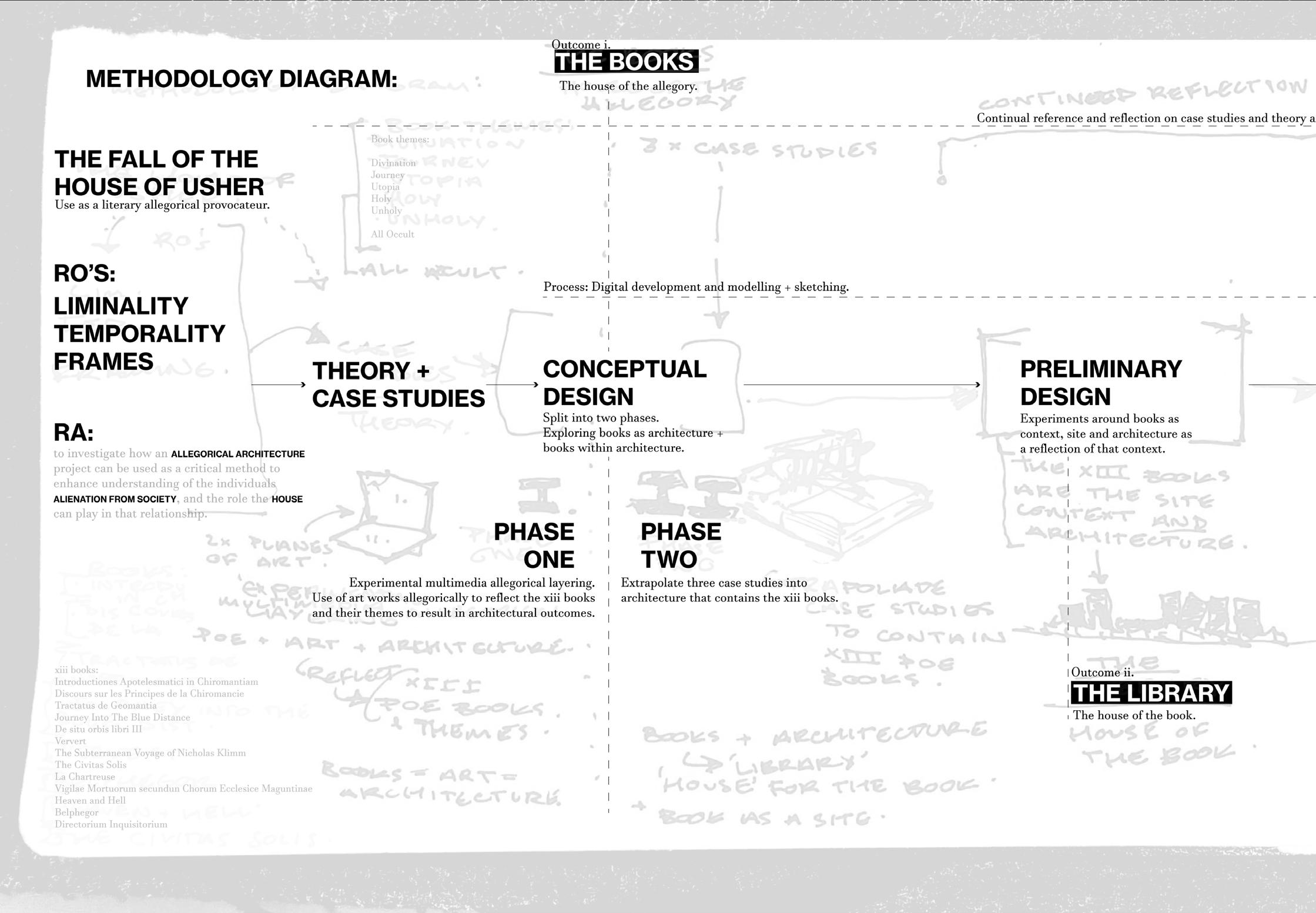

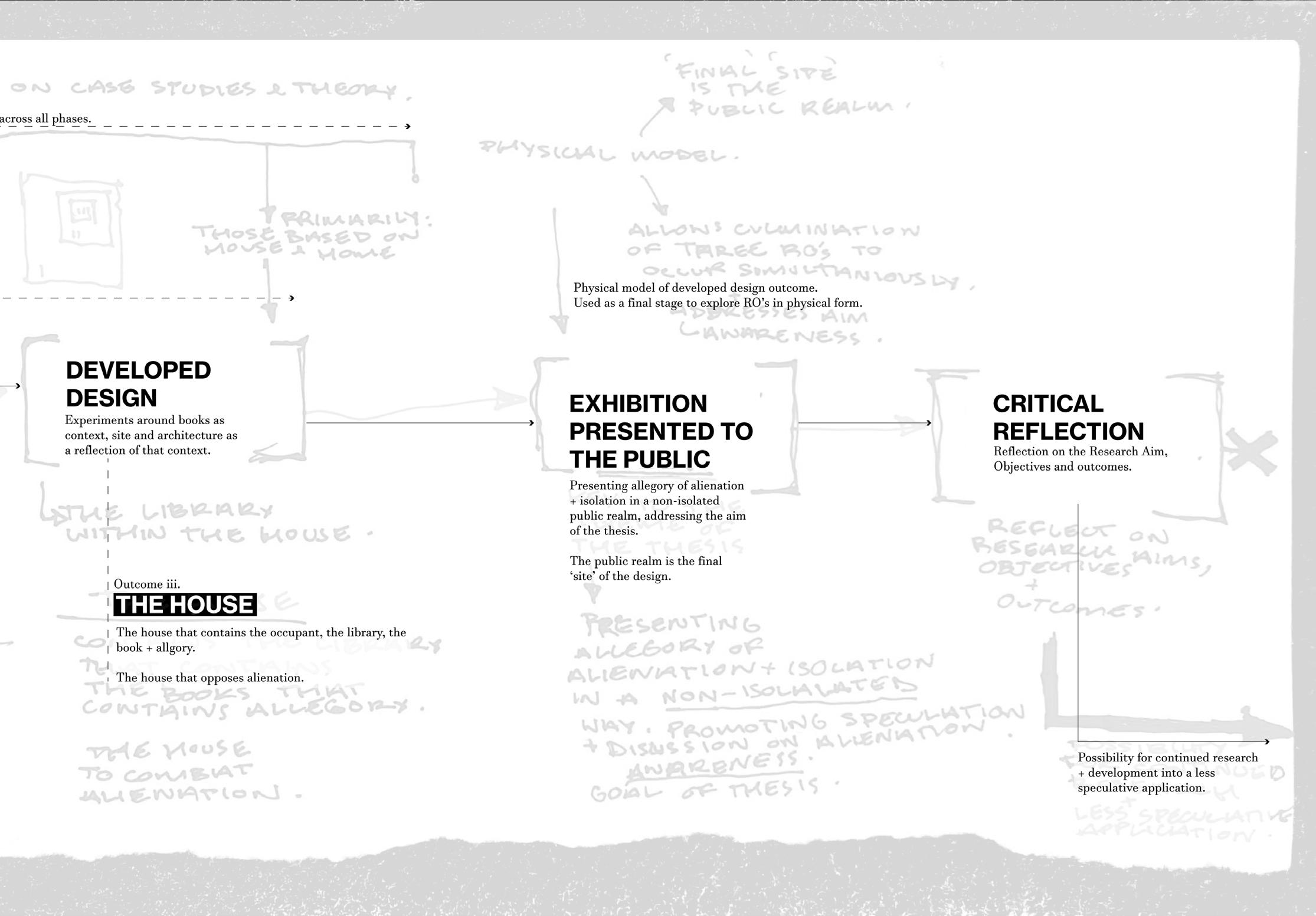

1.6 Design Methods & Process

1.7 Methodology Diagram

1.8 Research Scope

1.9 Thesis Structure

2.0 THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER

2.1 Introduction

2.2 The House

2.3 The Library

2.4 The Books

3.0 LITERATURE REIVIEW

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Alienation

3.3 Artifact

3.4 Dialectic Dialogues

3.5 Temporality

3.6 Critical Reflection

4.0 CONCEPT DESIGN PHASE ONE

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Experiment series 1 - Artifacts & Architecture

4.3 Experiment Series 2 - Artifacts & Architecture Revised

4.4 Critical Reflection

5.0 CONCEPT DESIGN PHASE TWO

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Experiment 1 - Adapting A Nightmare Within a Nightmare

5.3 Experiment 2 - Adapting Chiba Golf Course

5.4 Experiment 3 - Adapting Ghost Ship

5.5 Experiment 4 - Adapting Combined

5.6 Conceptual Design Critical Reflection.

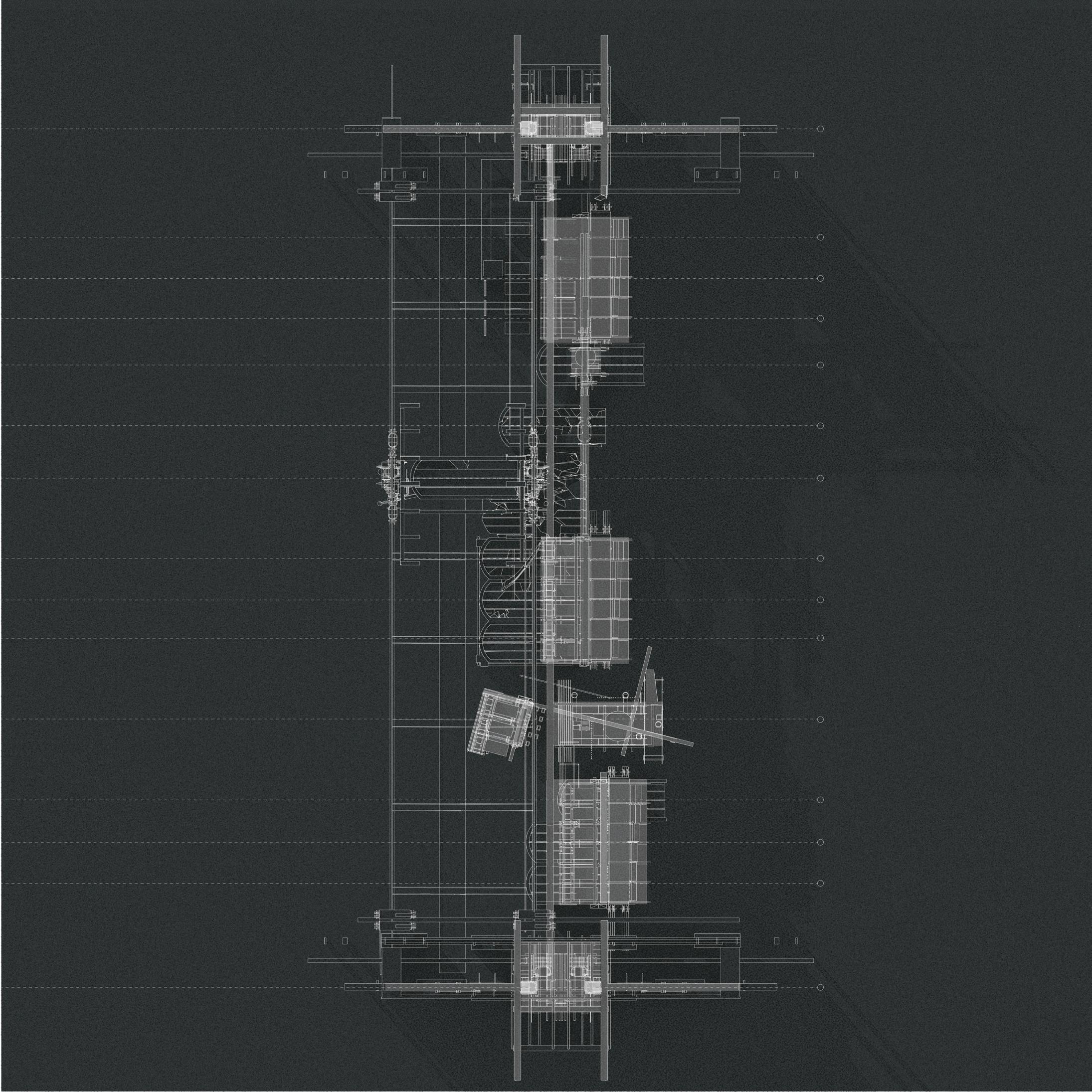

6.1 Introduction

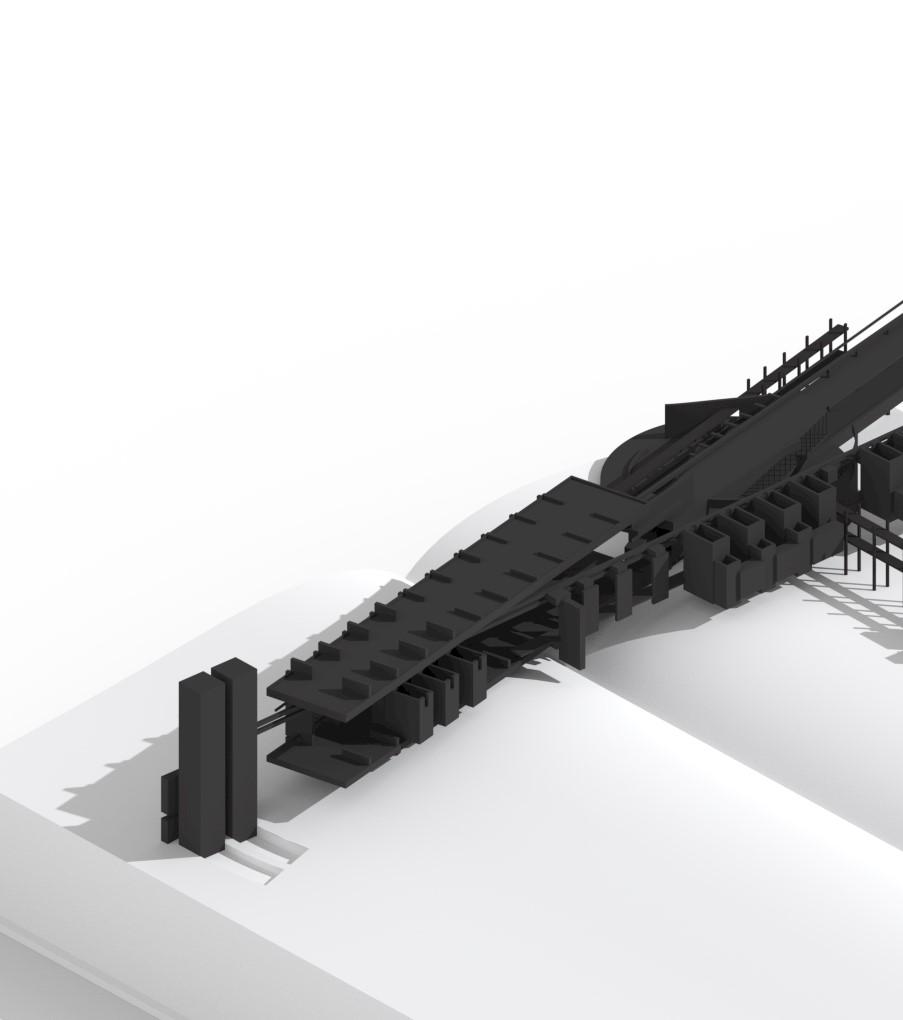

6.2 Experiment One - Reexamining the Library

6.3 Experiment Two - Reorganising the Library

6.4 Experiment Three – The Tarn

6.5 Experiment Four – The Book as Landscape

6.6 Experiment Five – Books & Ruin

6.7 Experiment Six – Landscape Extremes

6.8 Critical Reflection

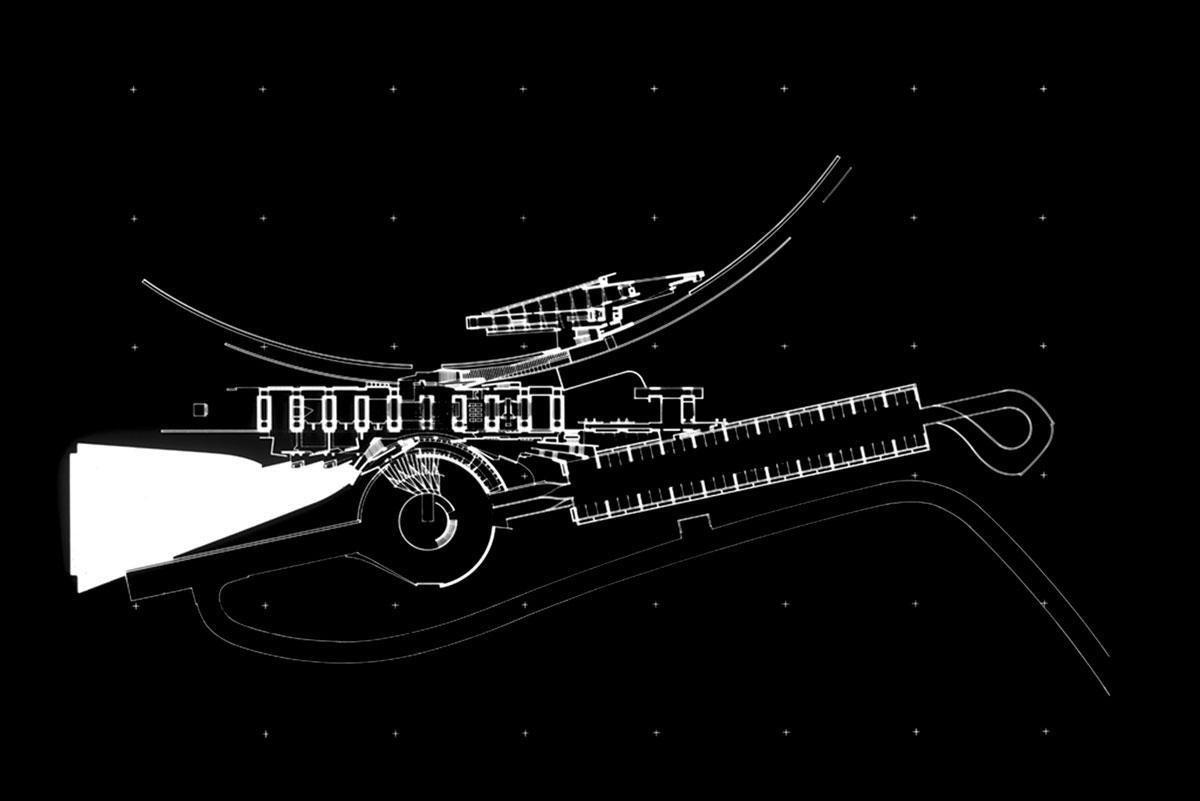

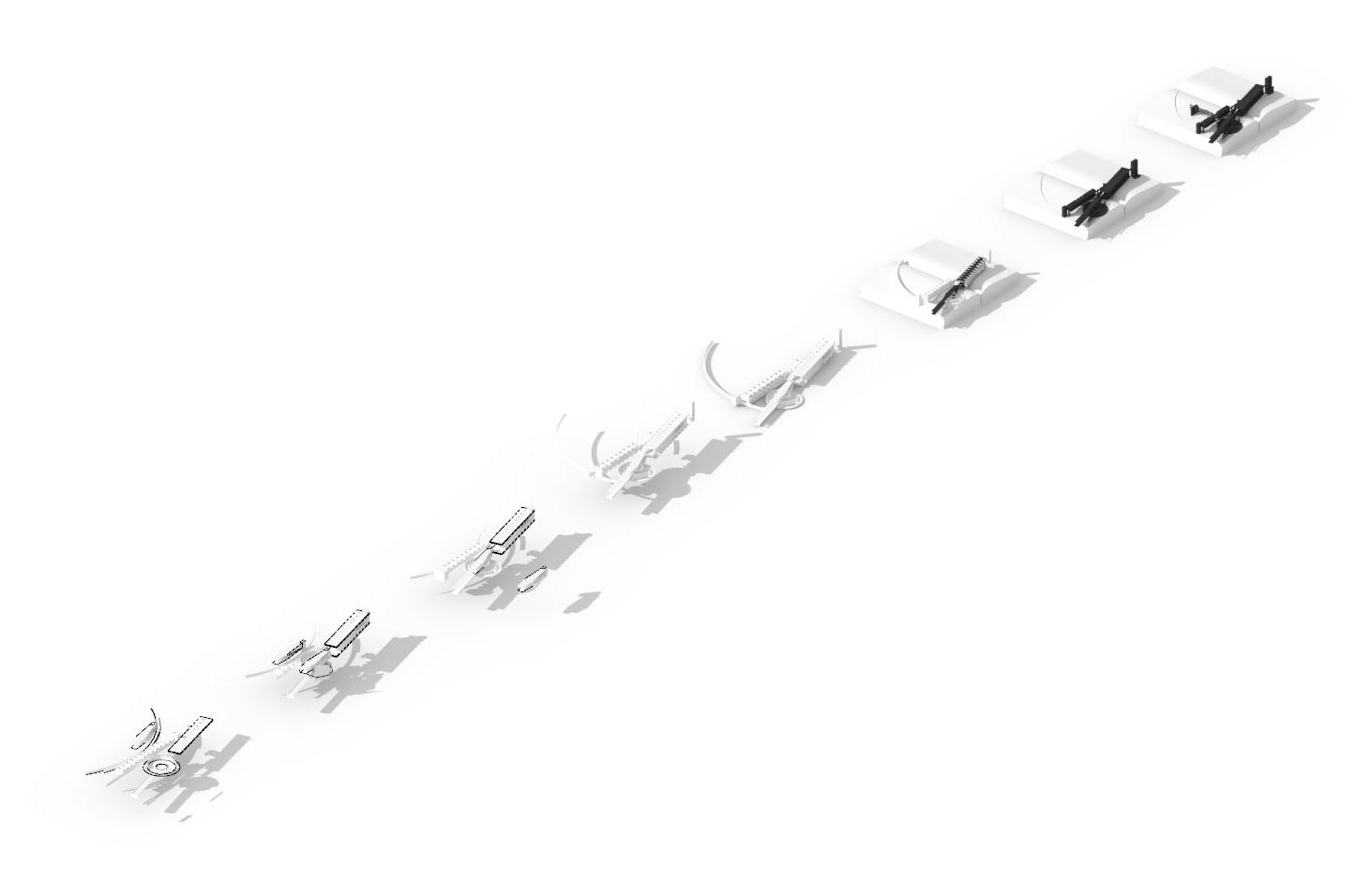

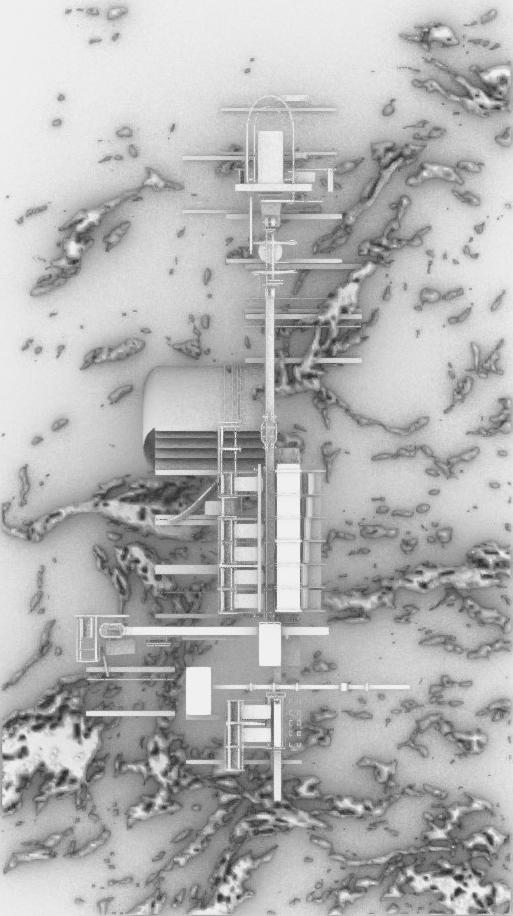

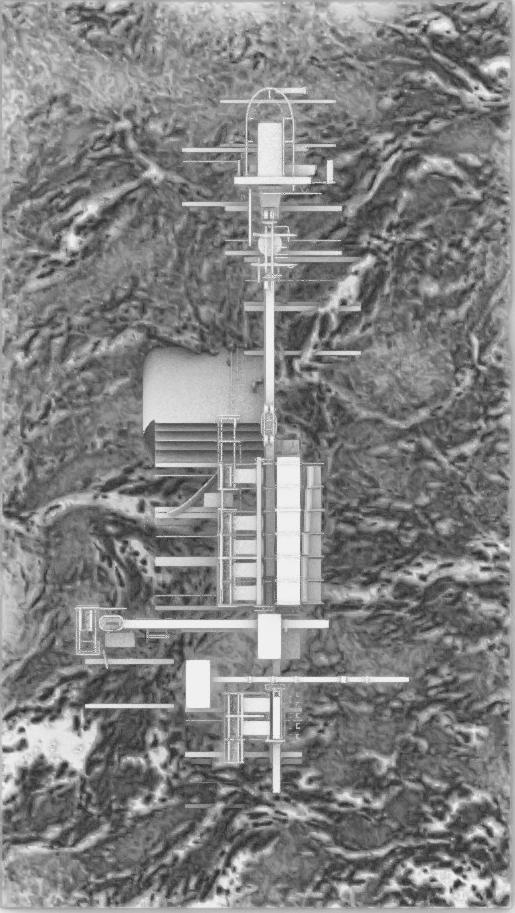

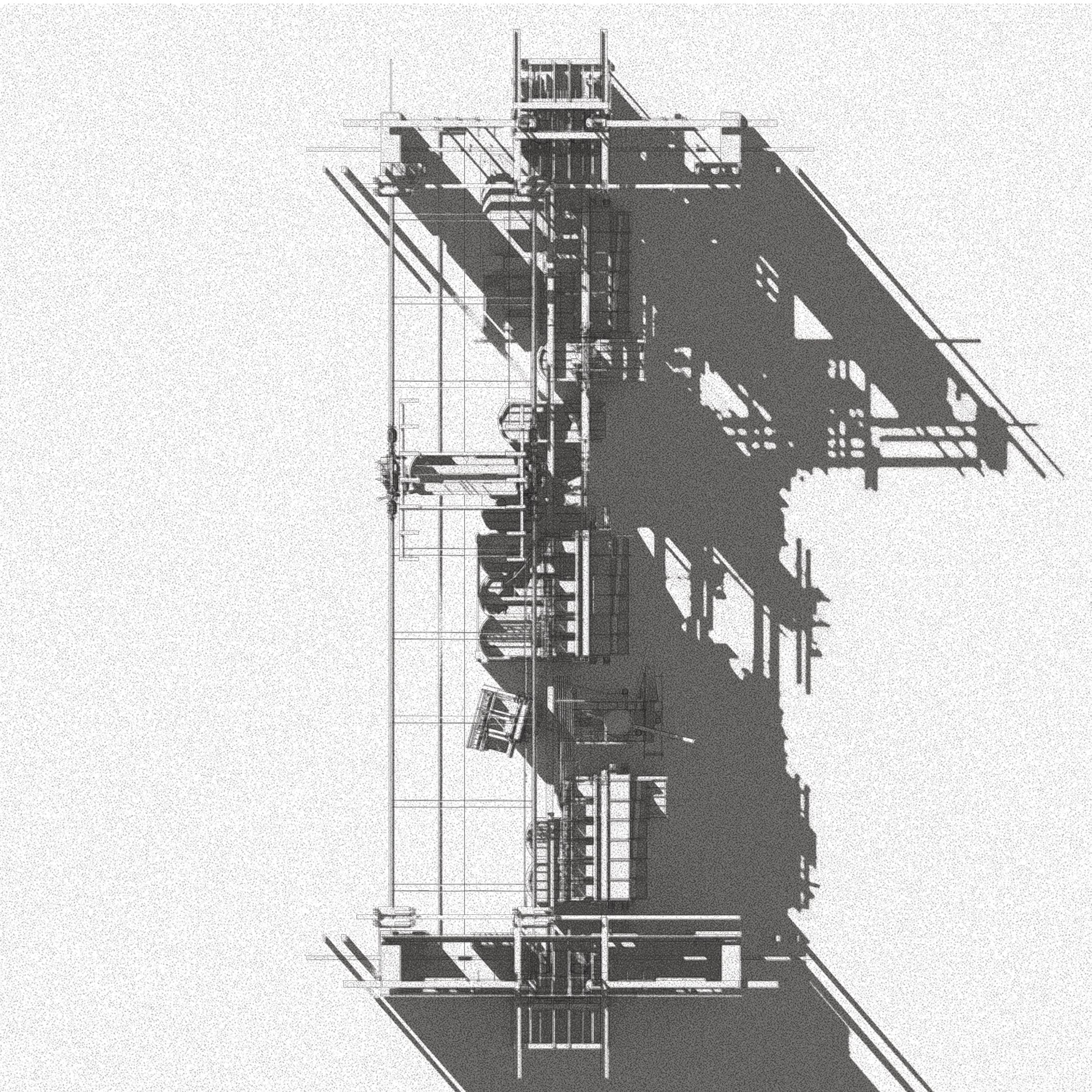

PRELIMINARY DESIGN PHASE

7.1 Introduction

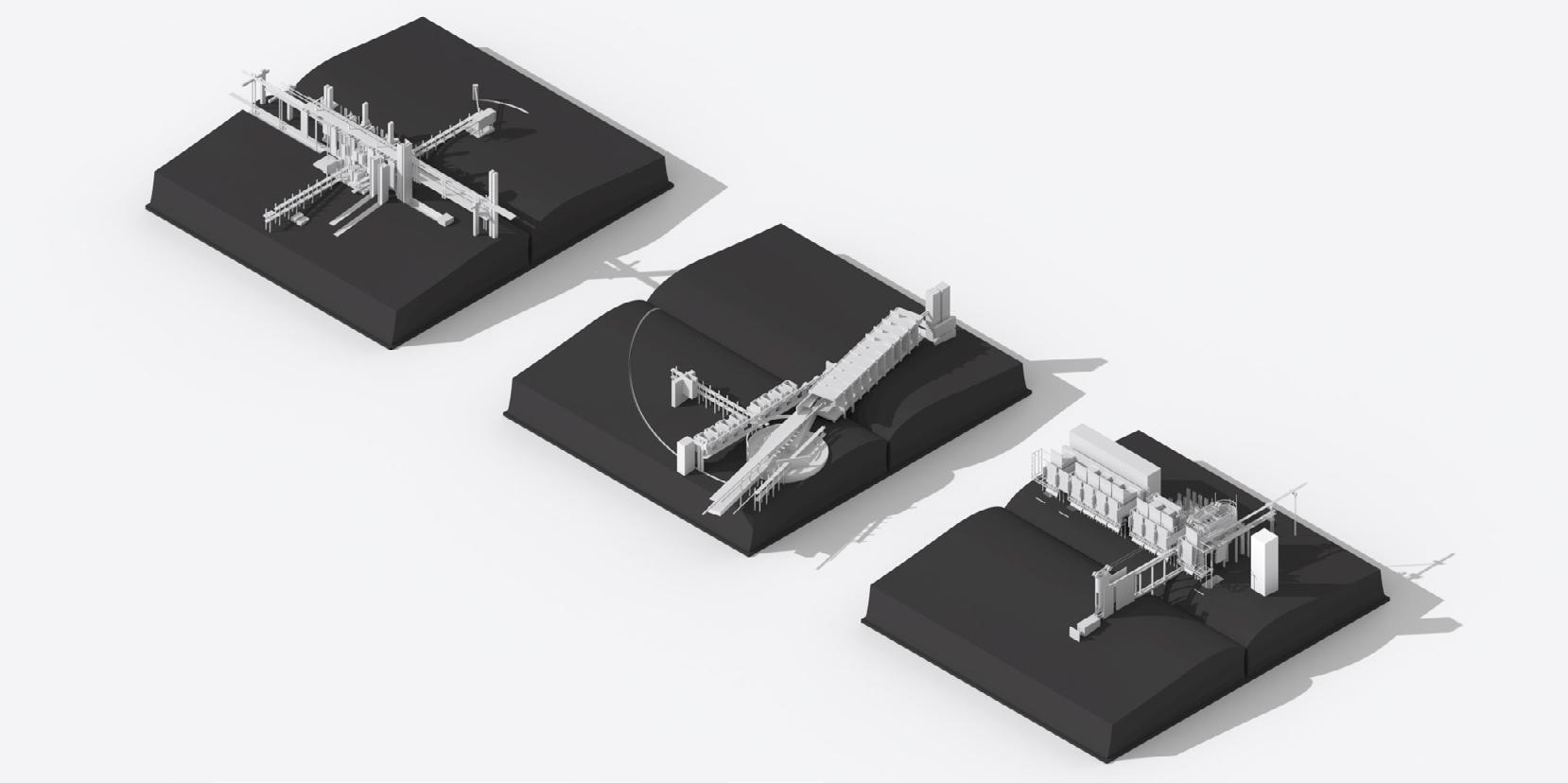

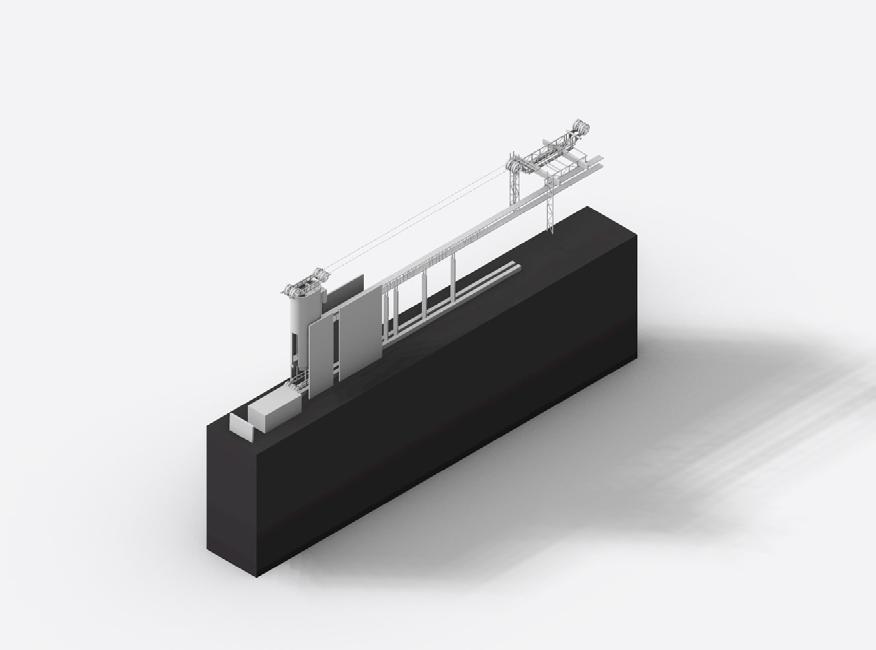

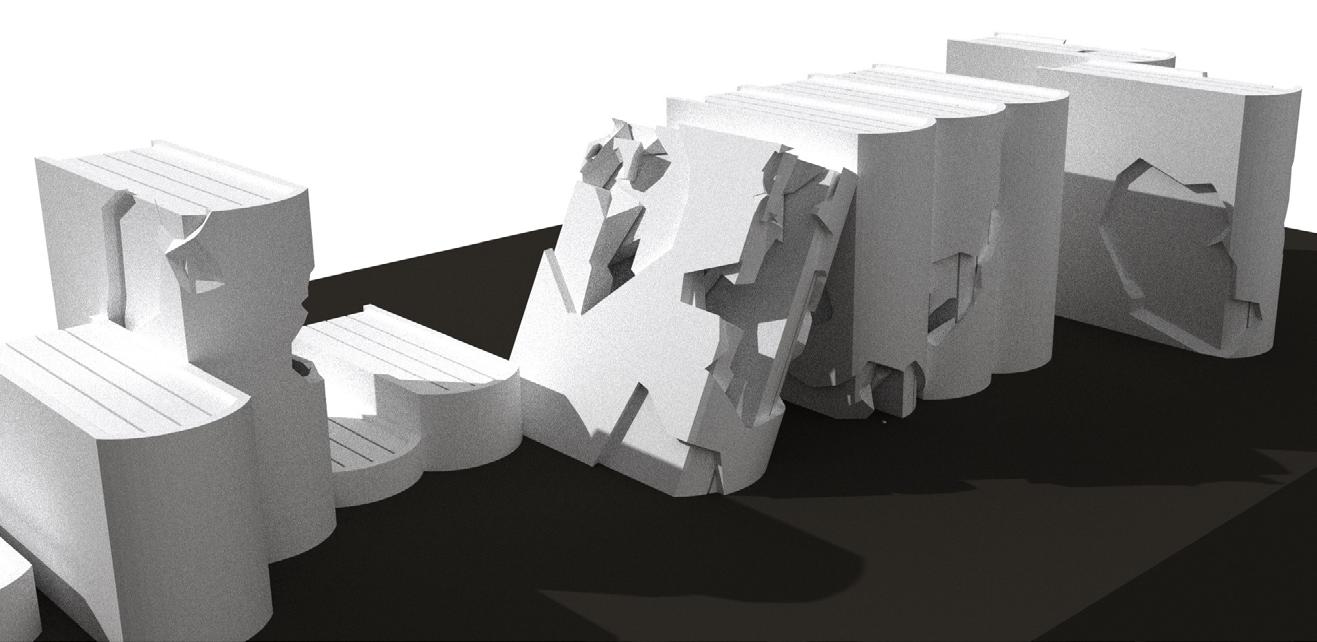

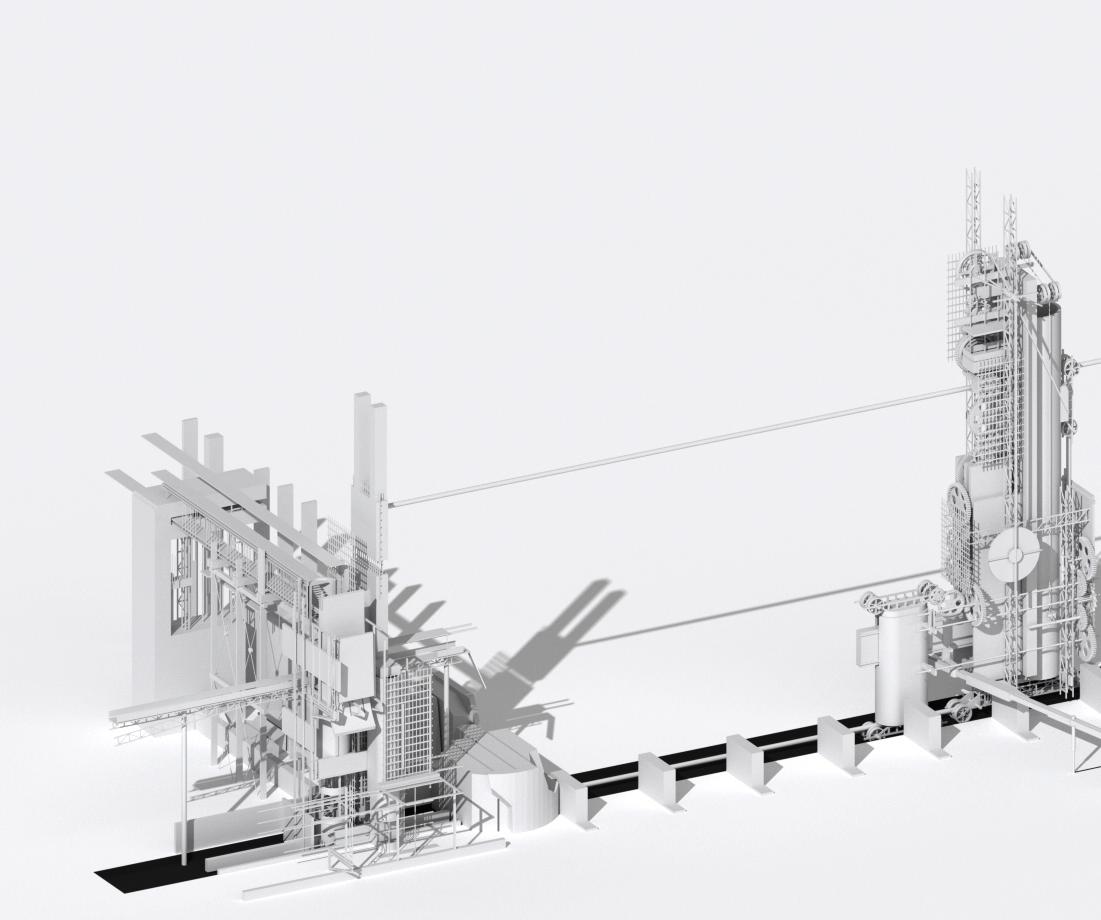

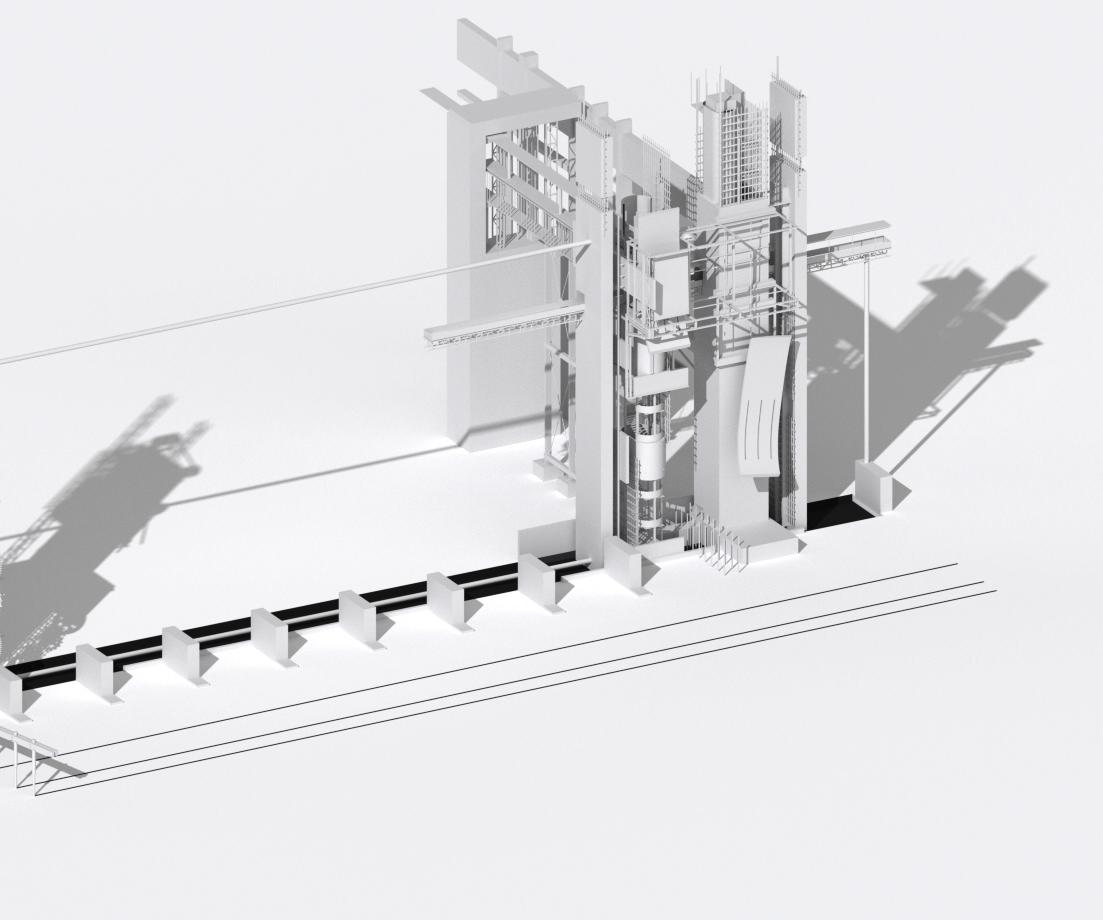

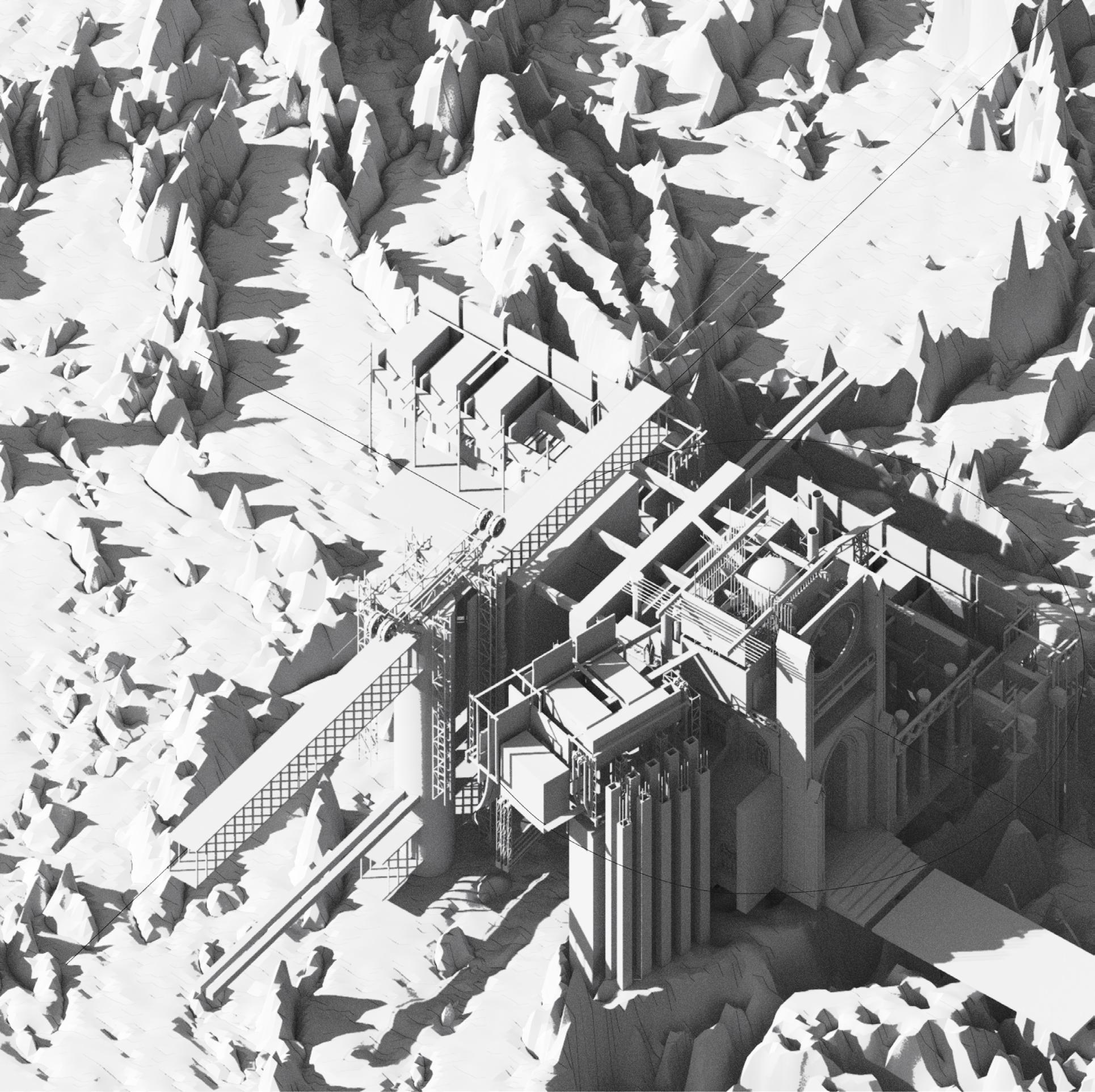

7.2 Experiment One - The Bookends

7.3 Experiment Two - The Bookmark

7.4 Experiment Three - Bookends & Bookmark

7.5 Experiment Four - Bookends, Bookmark, & Library

7.6 Experiment Five - The Bookshelf

7.7 Critical Reflection

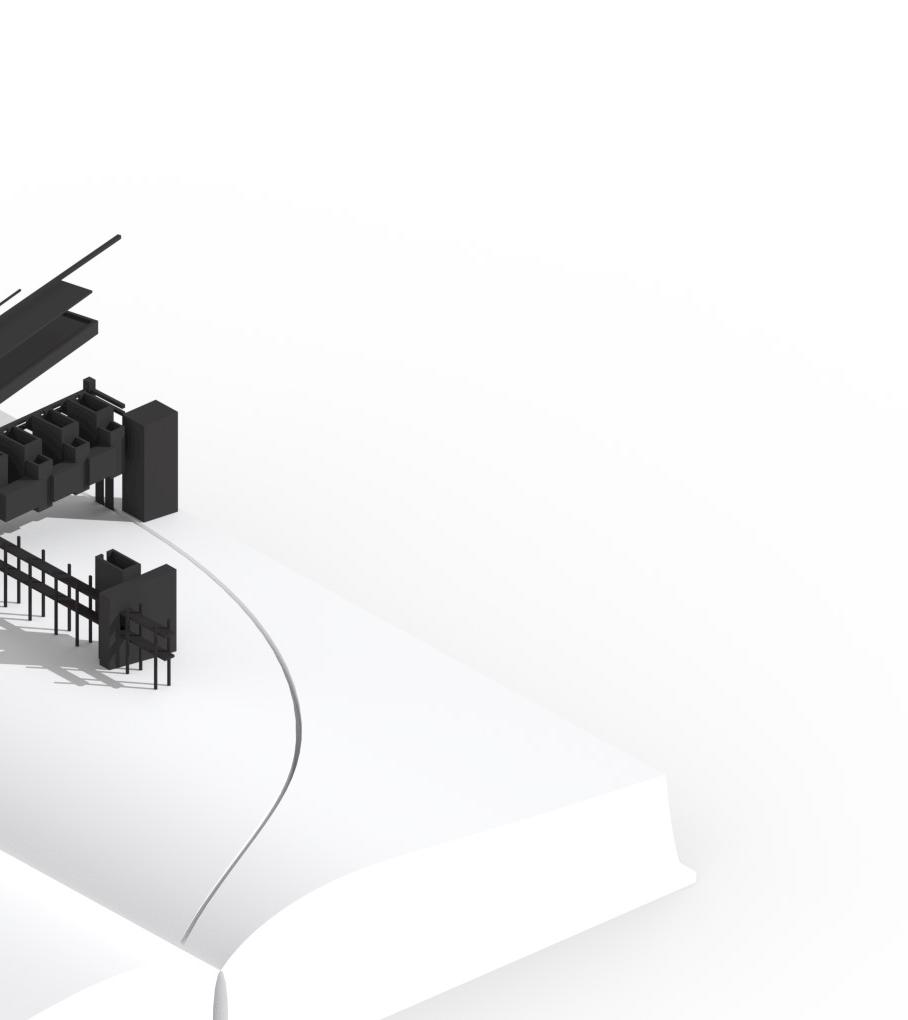

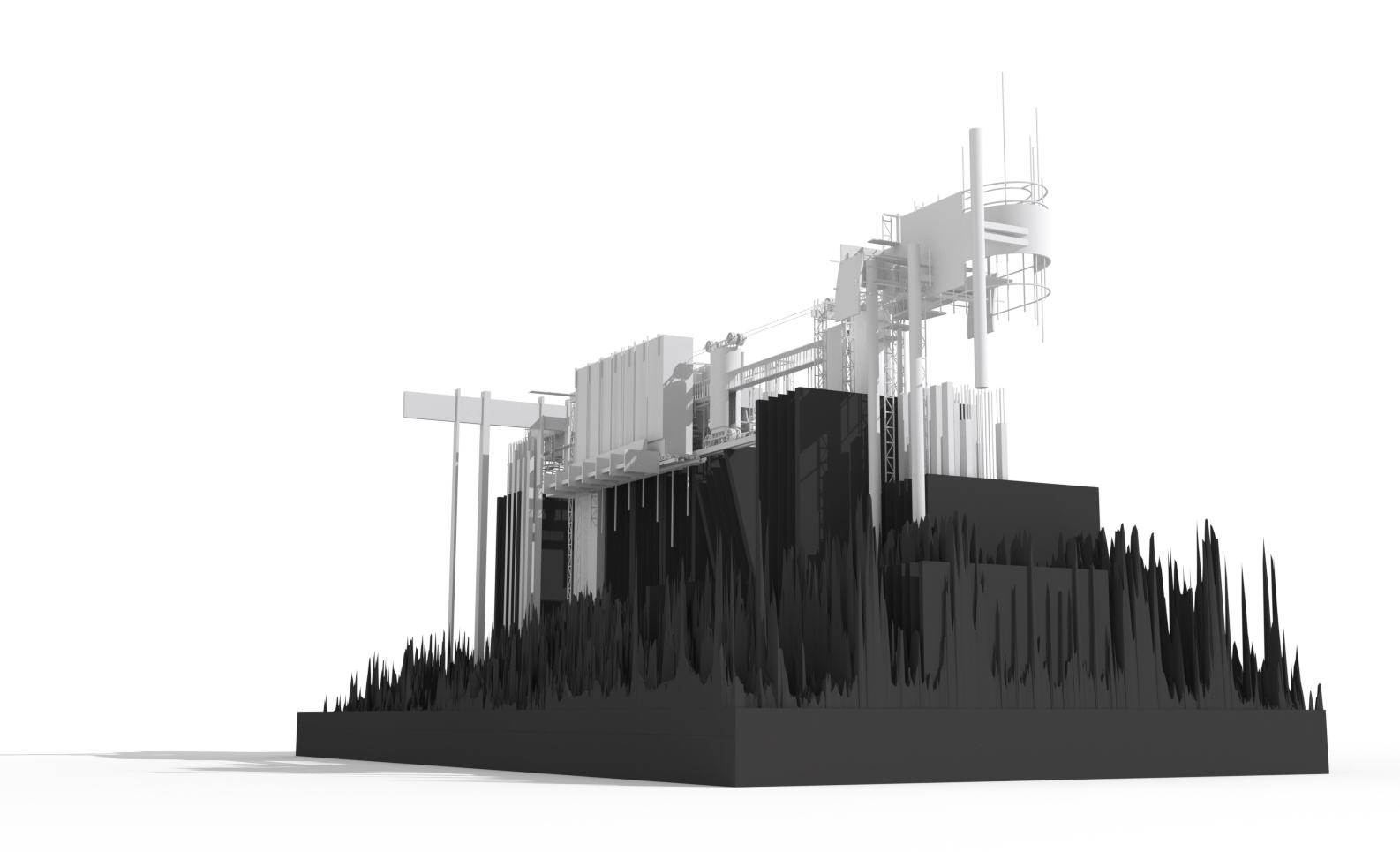

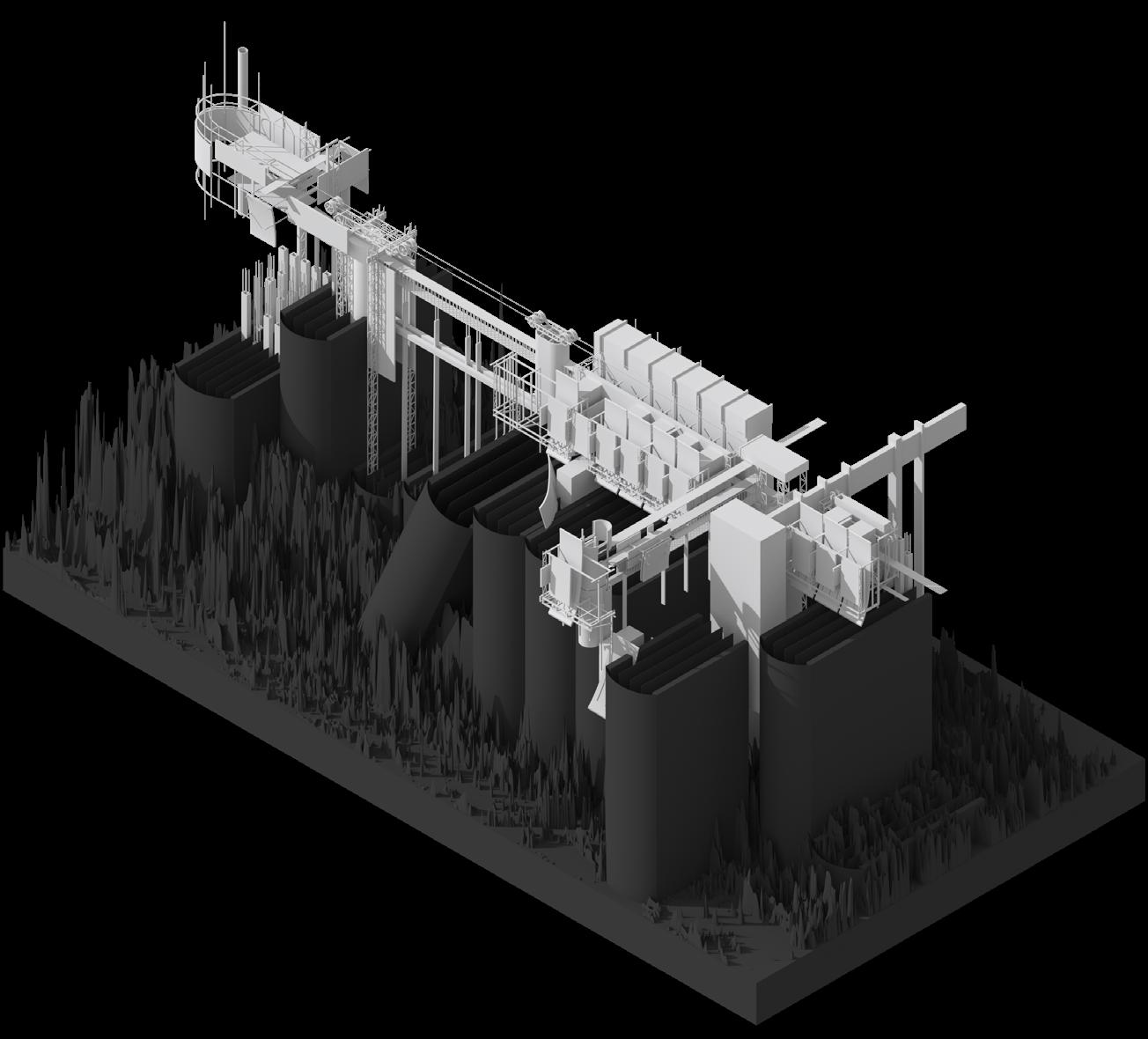

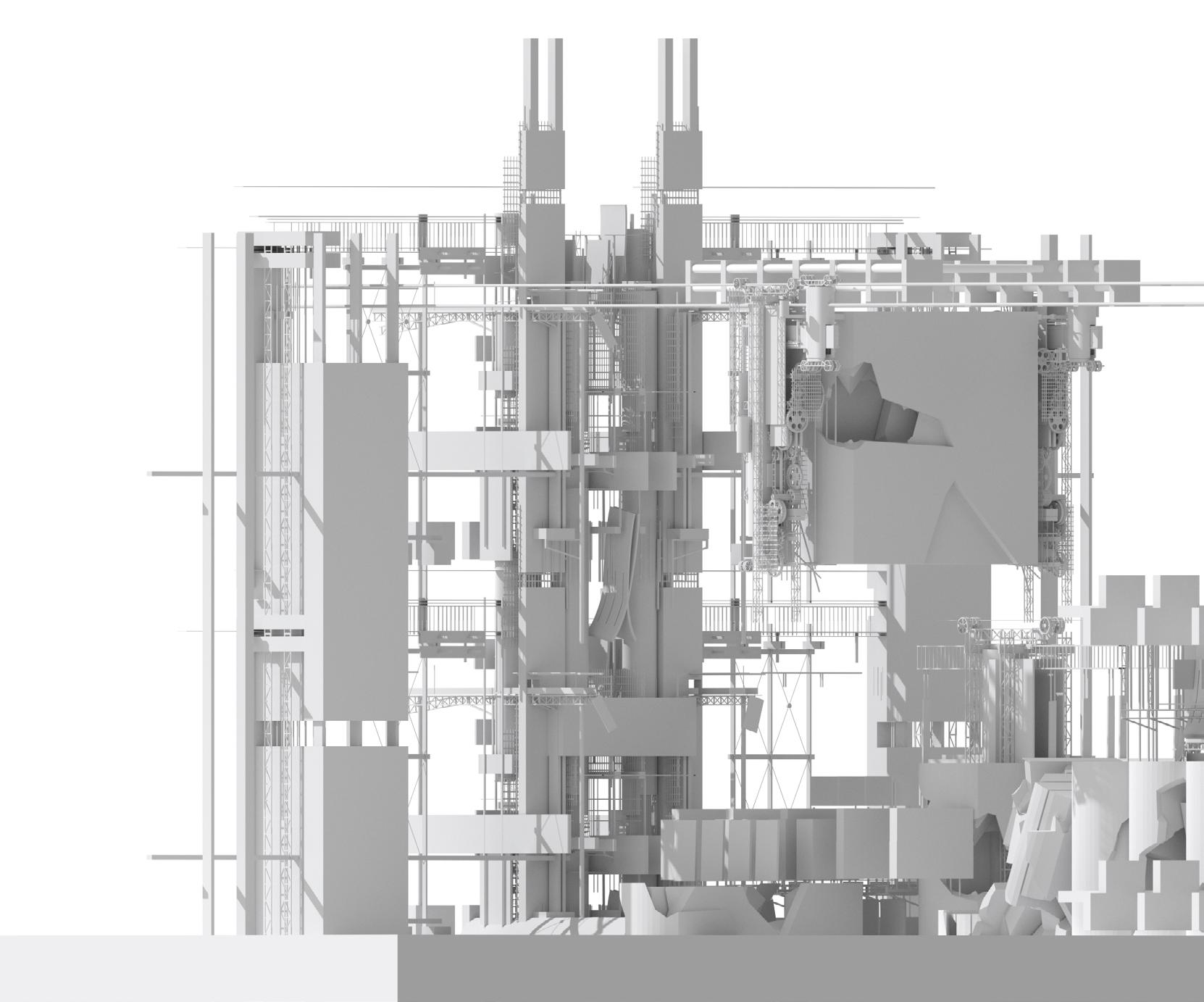

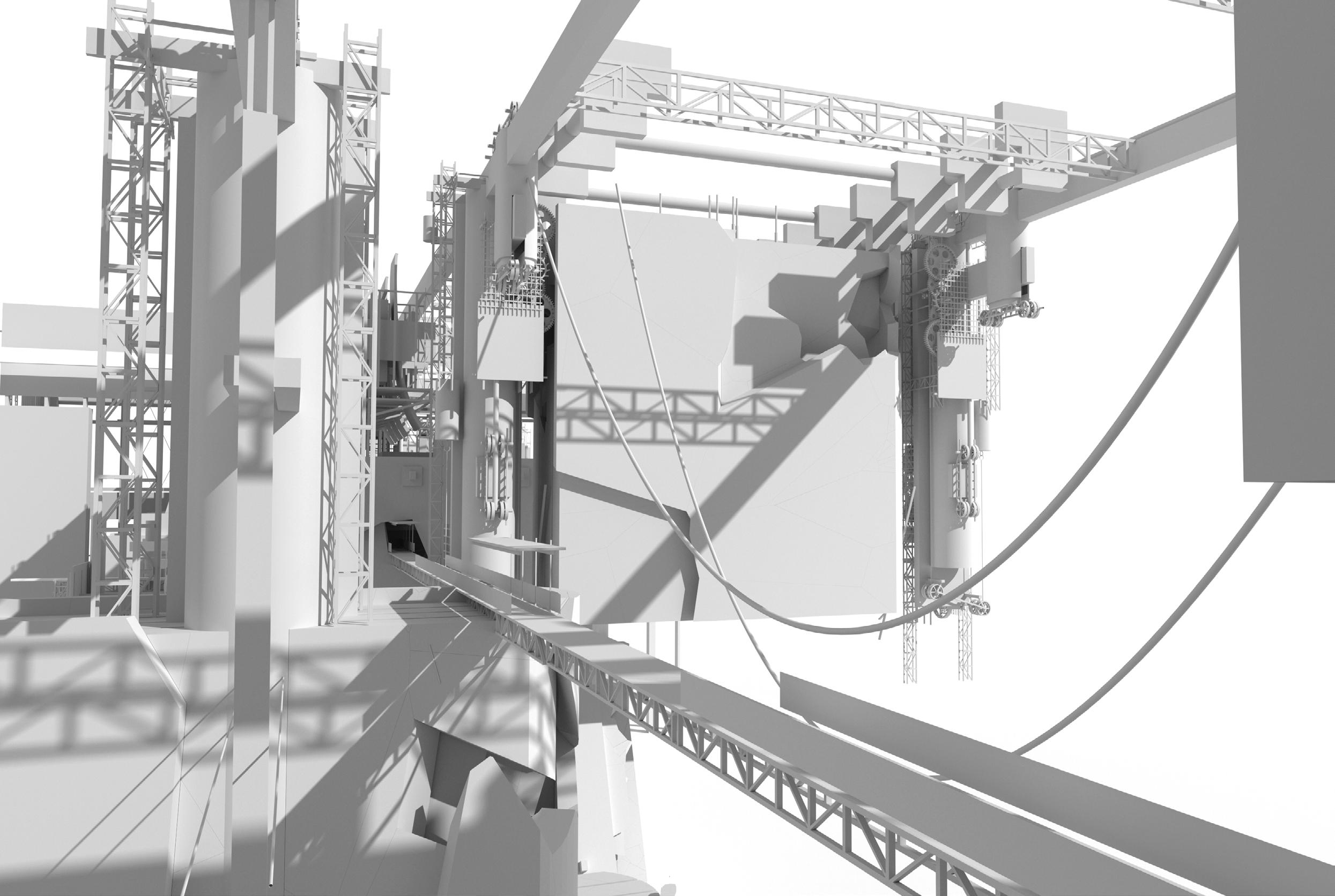

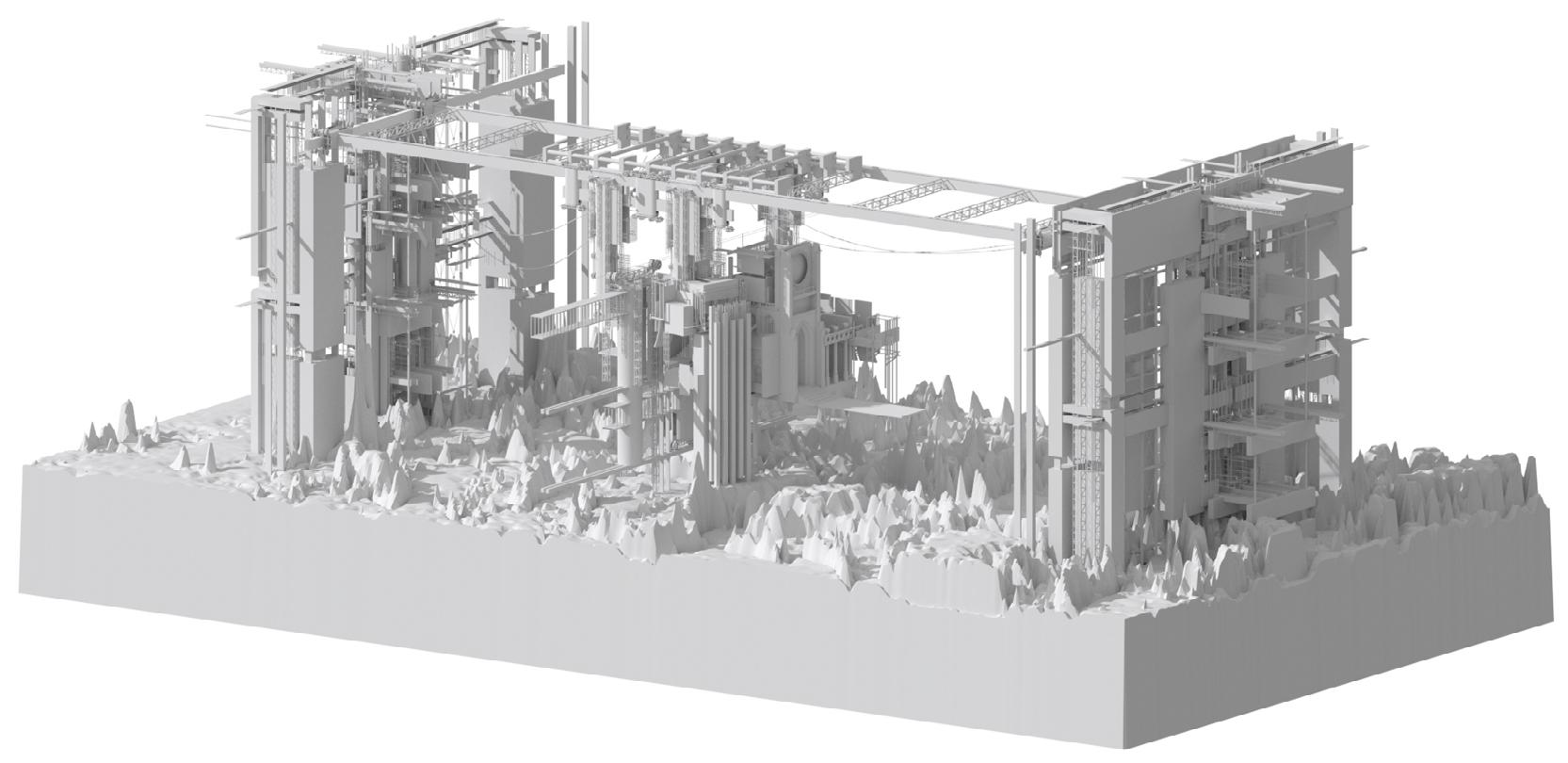

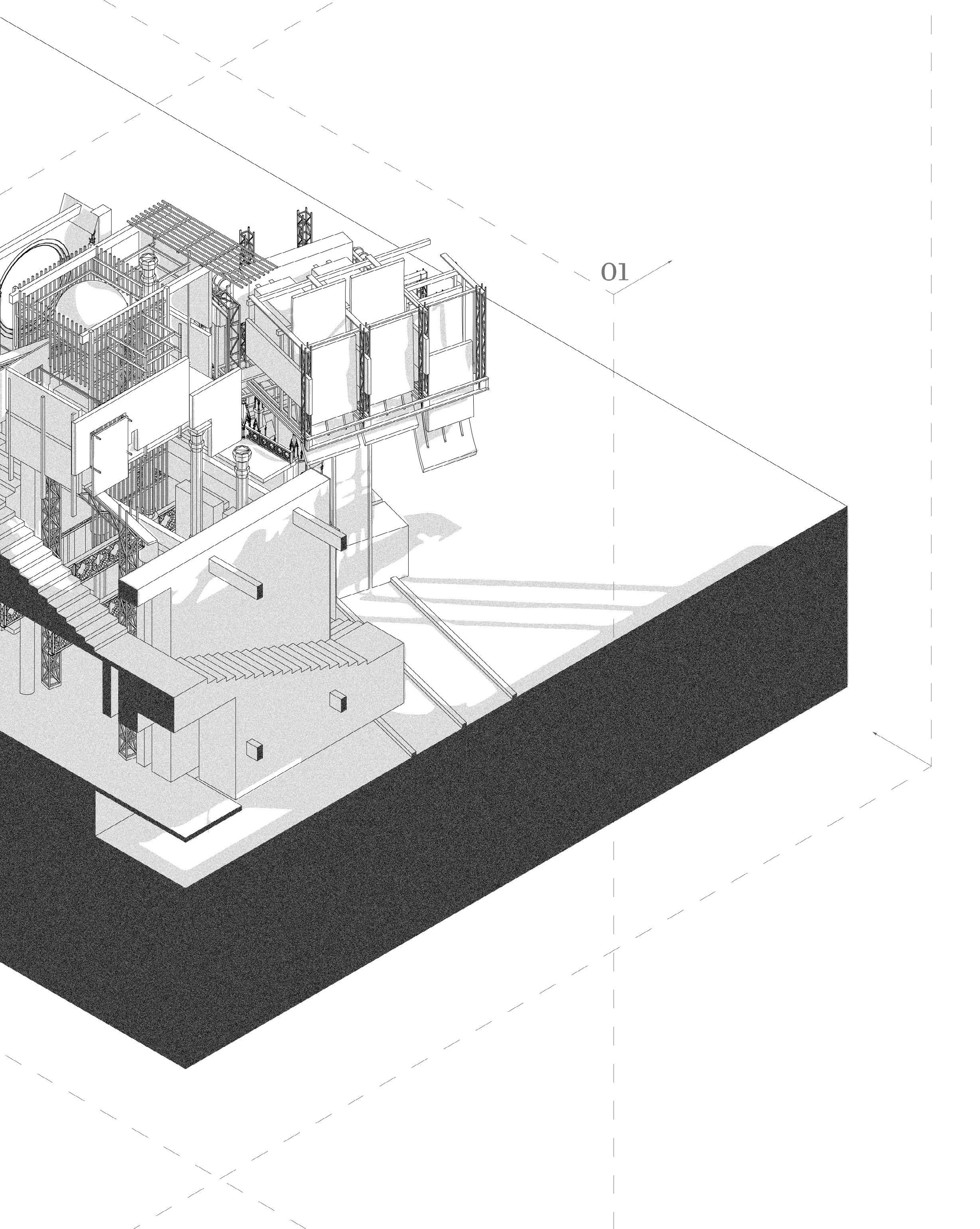

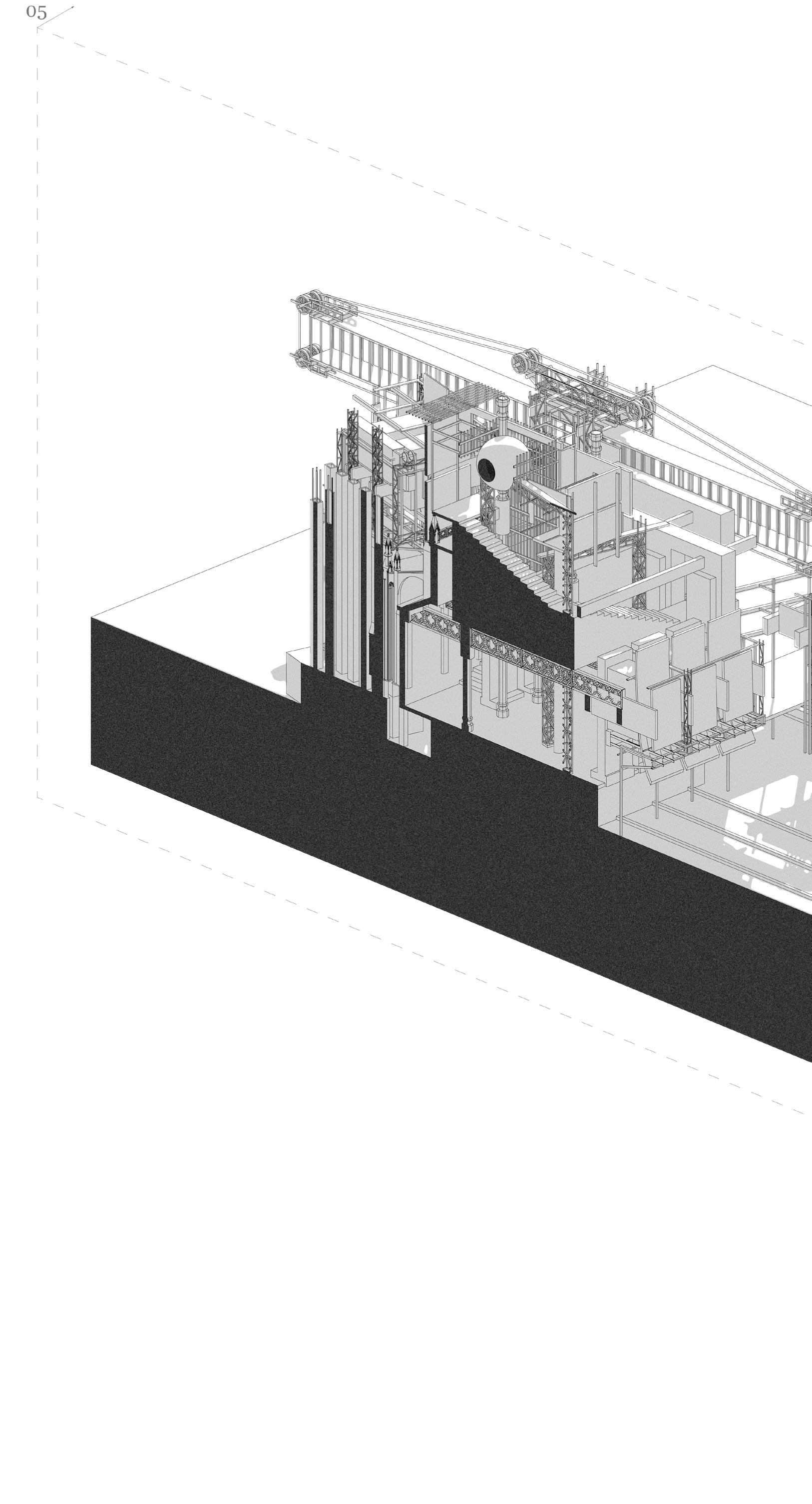

8.0 DEVELOPED DESIGN

8.1 Introduction

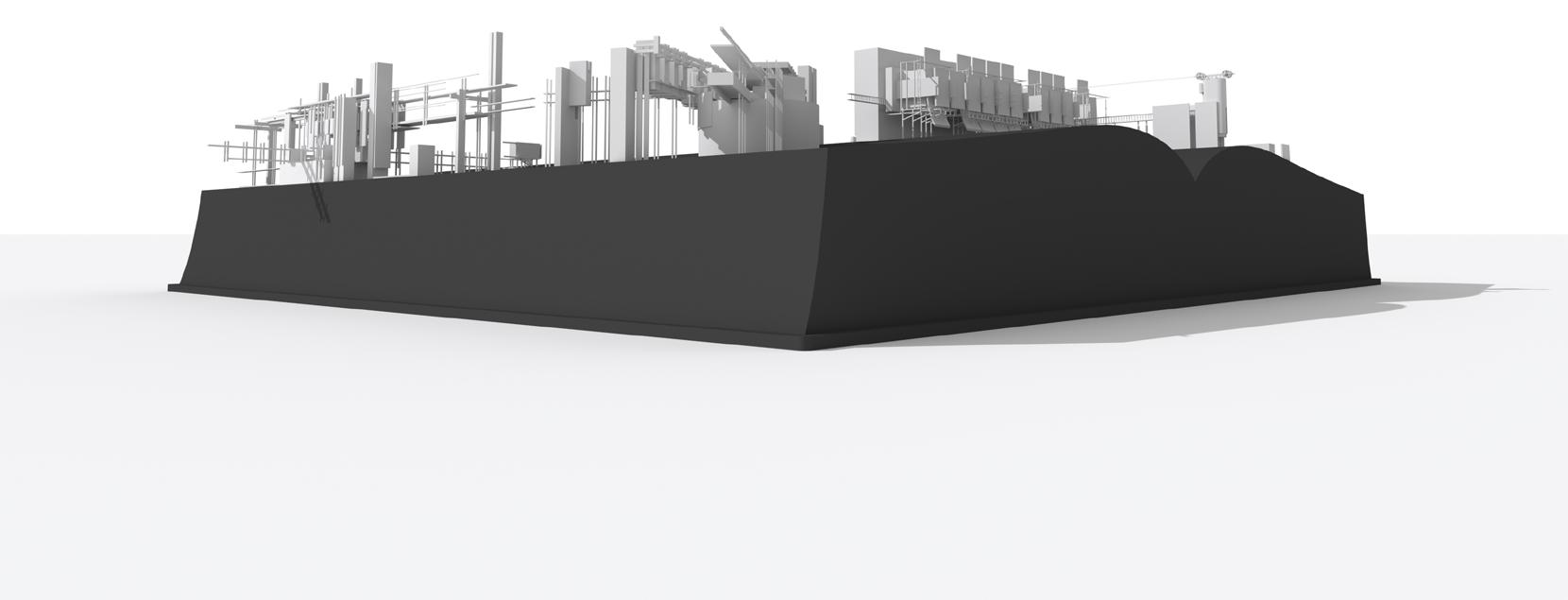

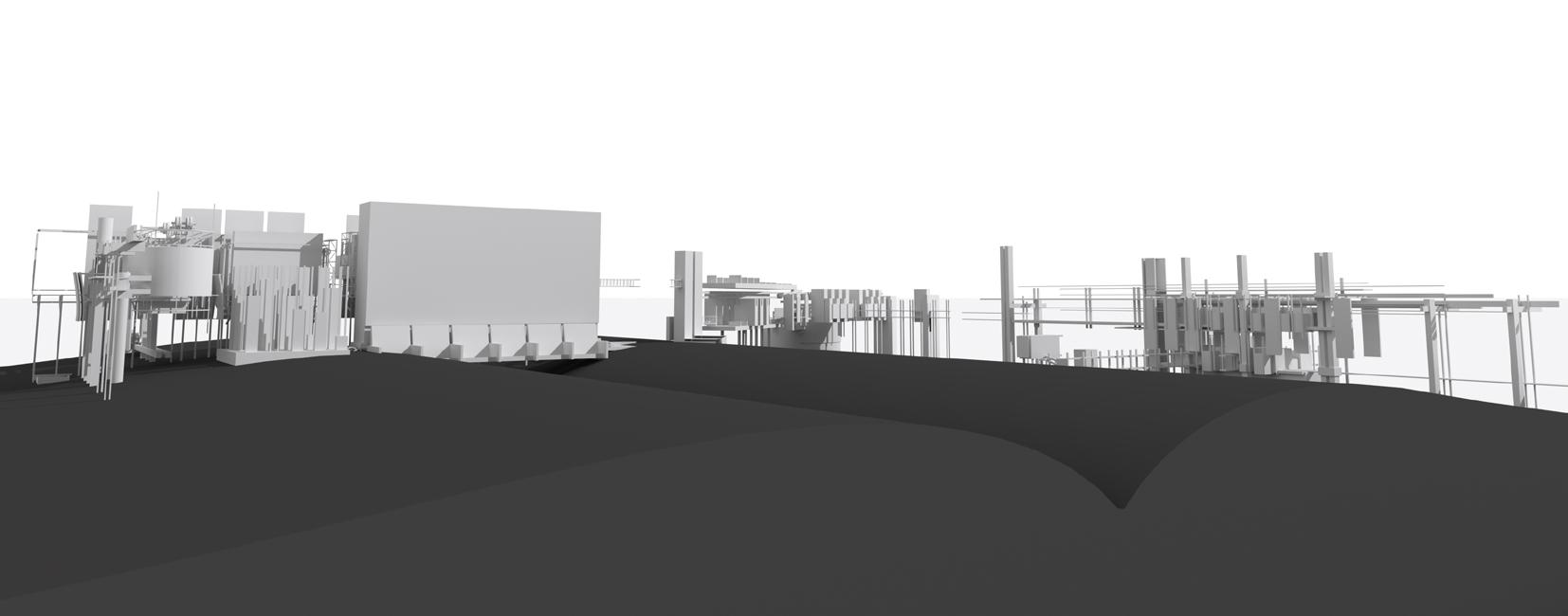

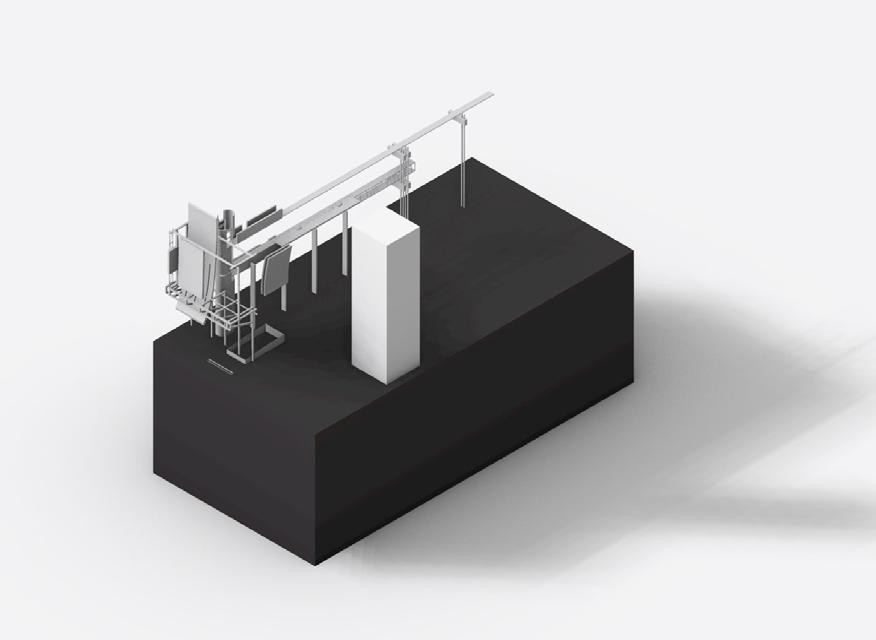

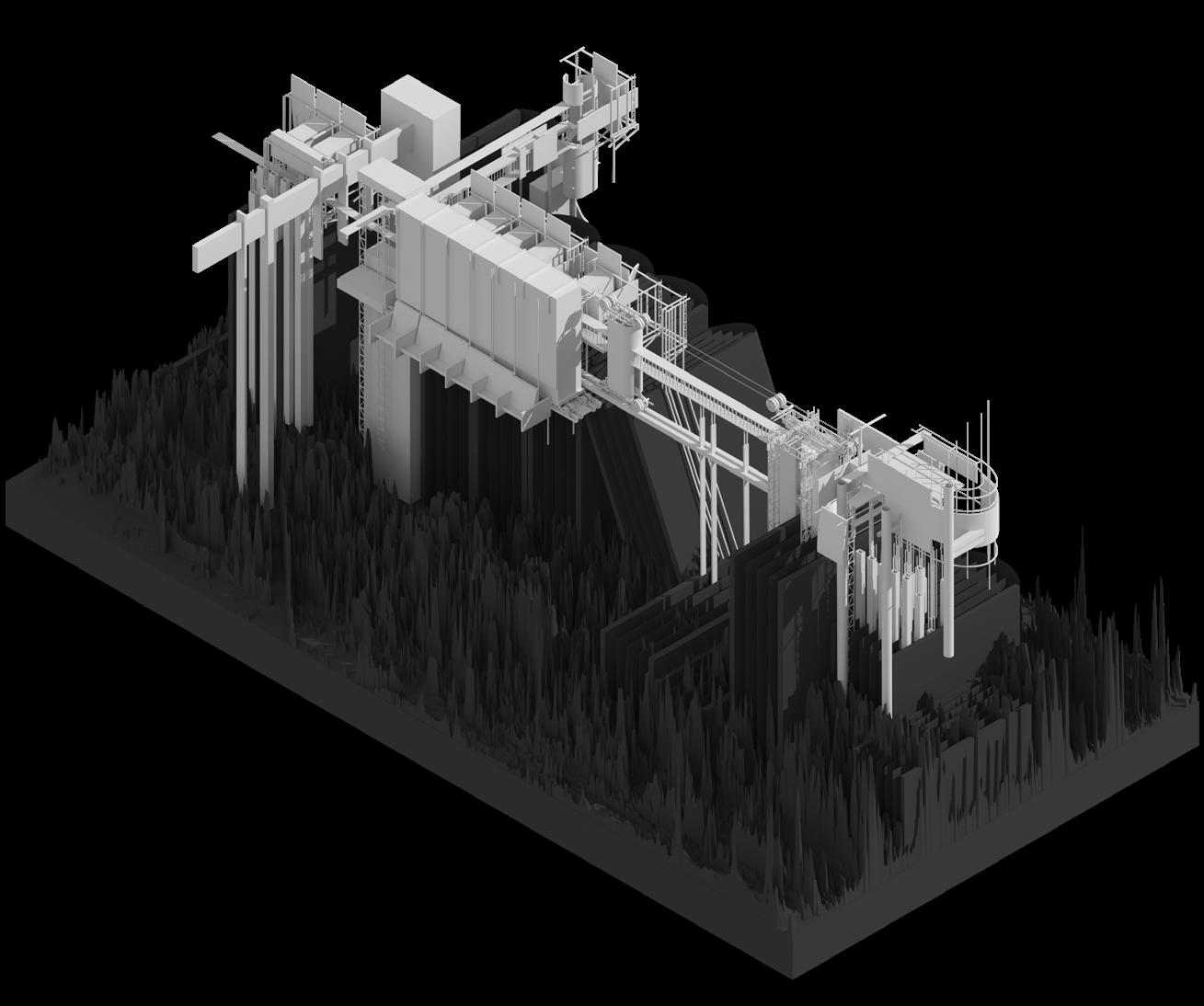

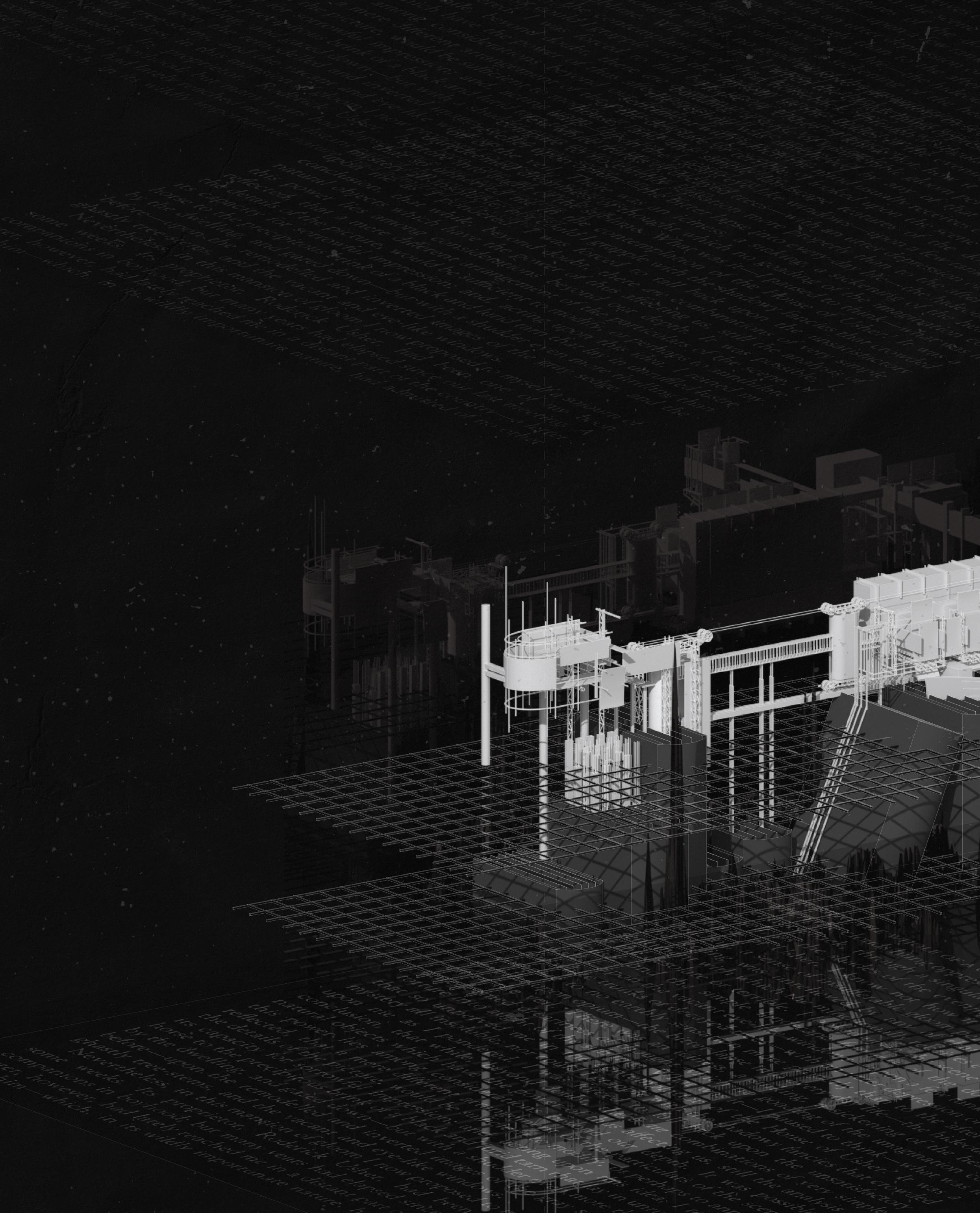

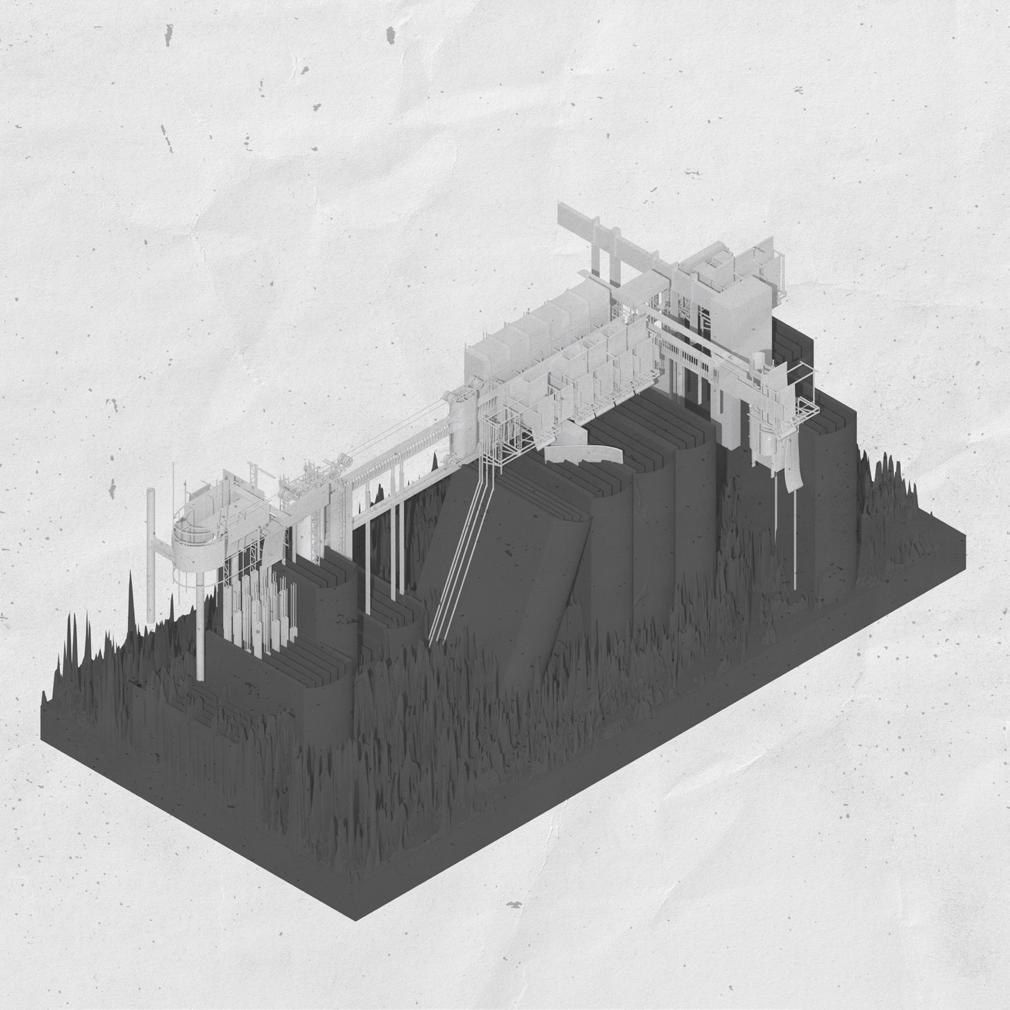

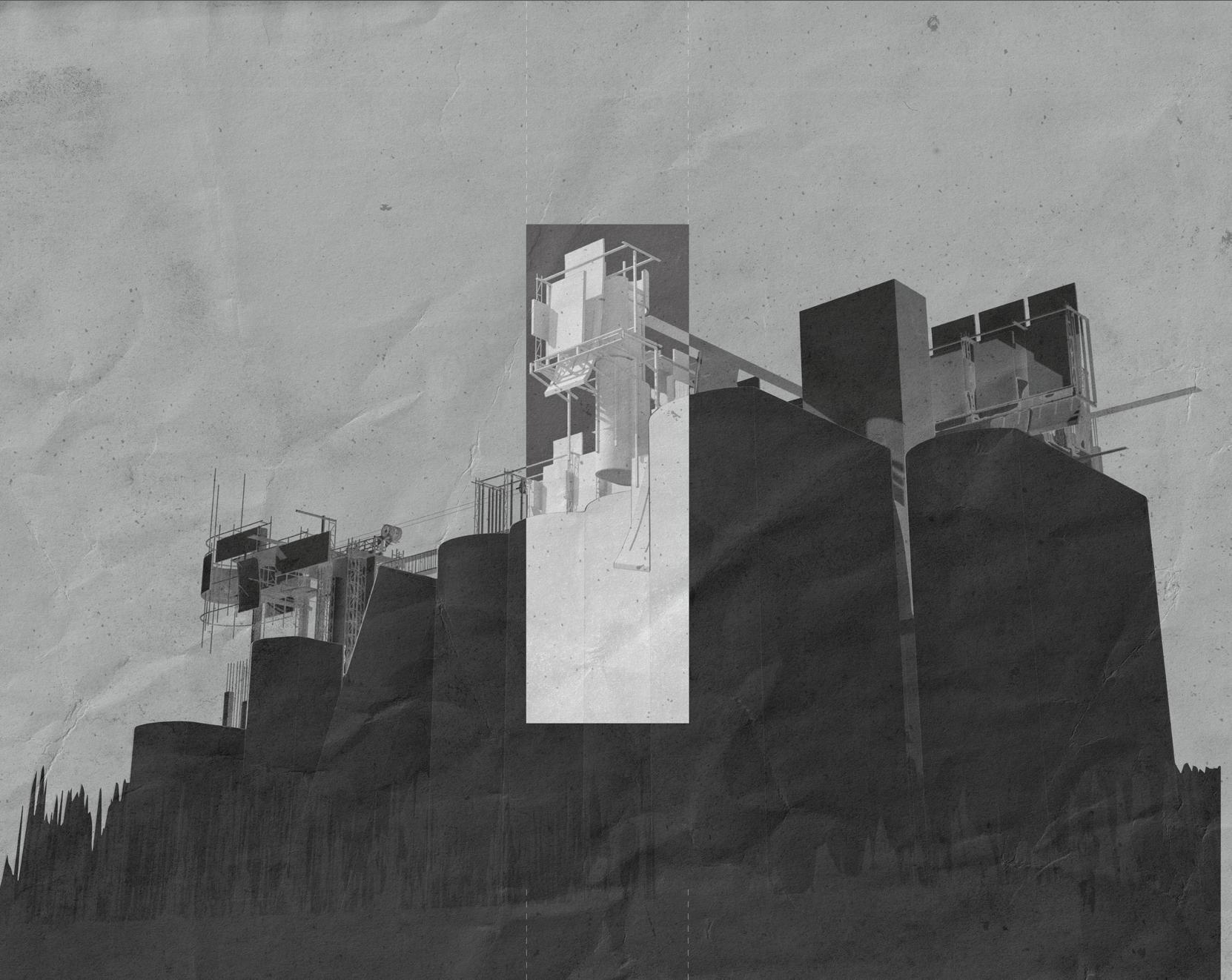

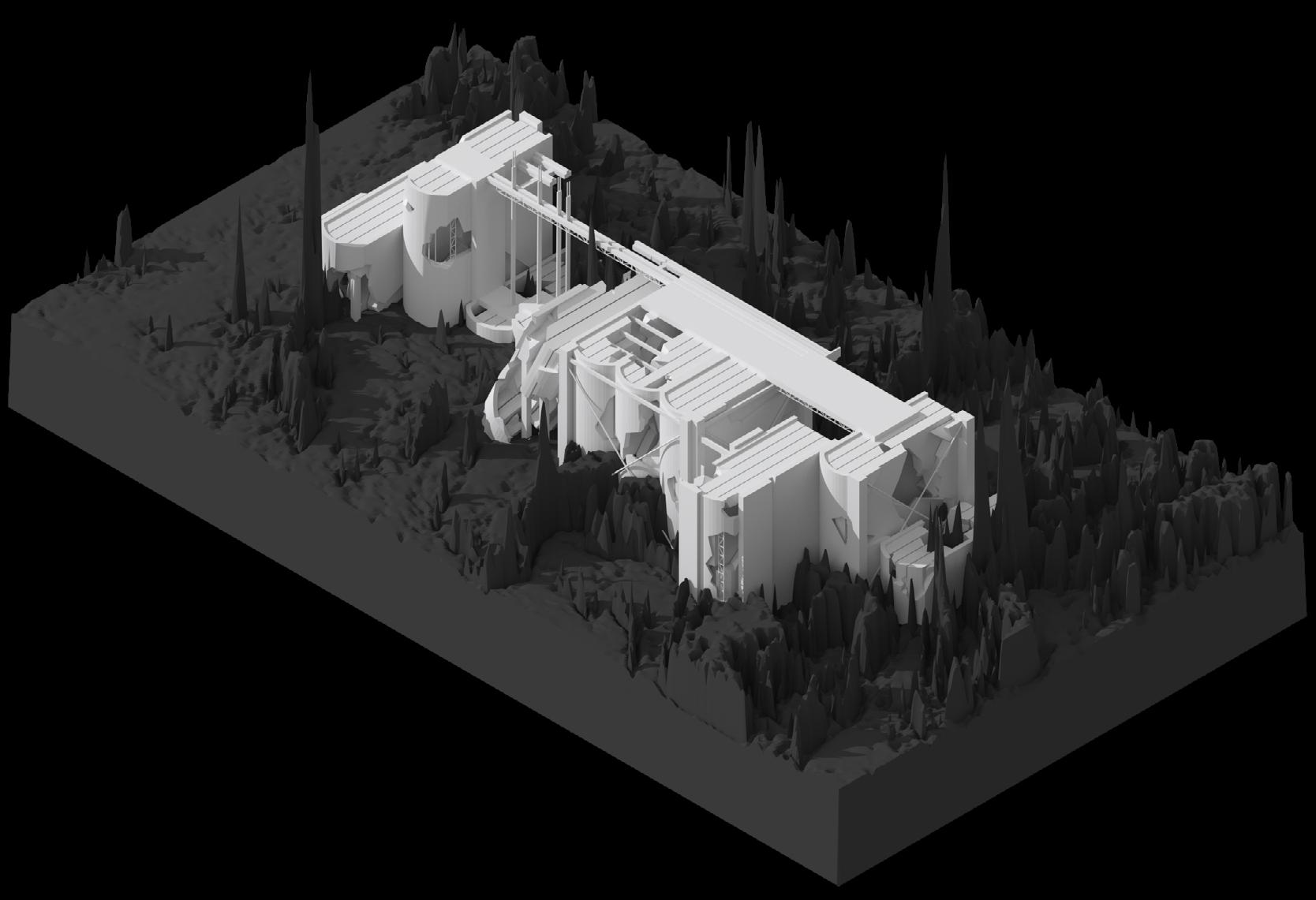

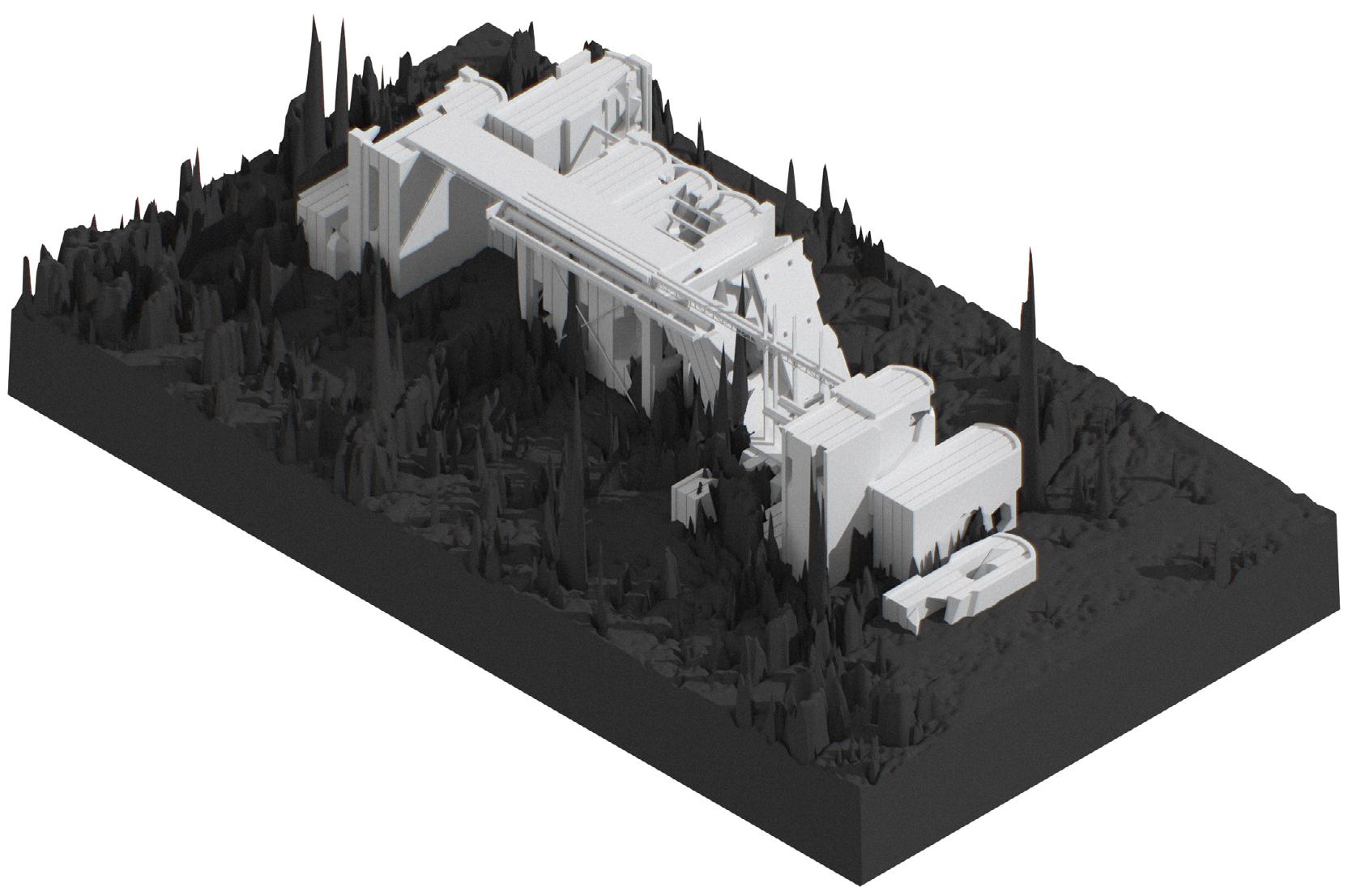

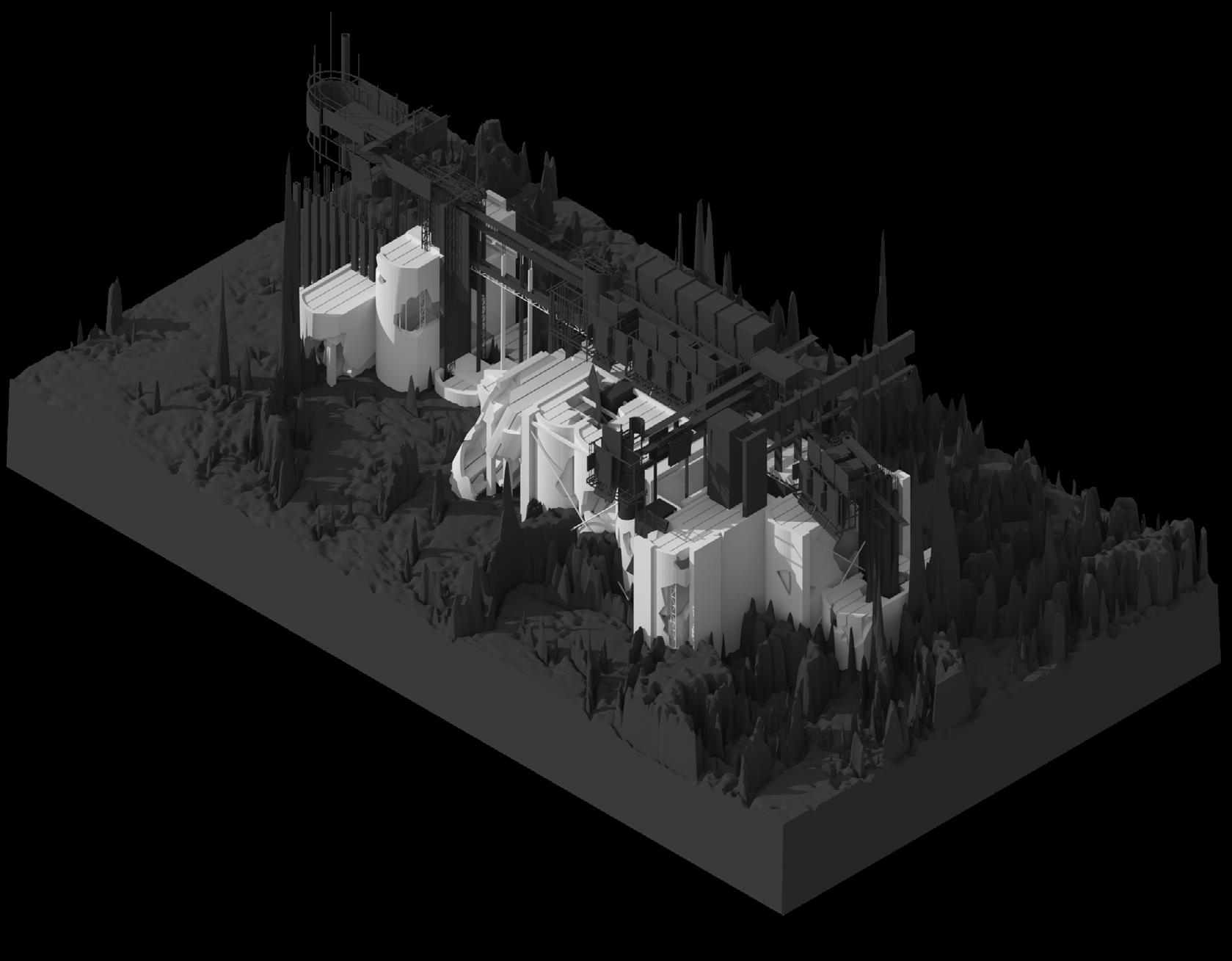

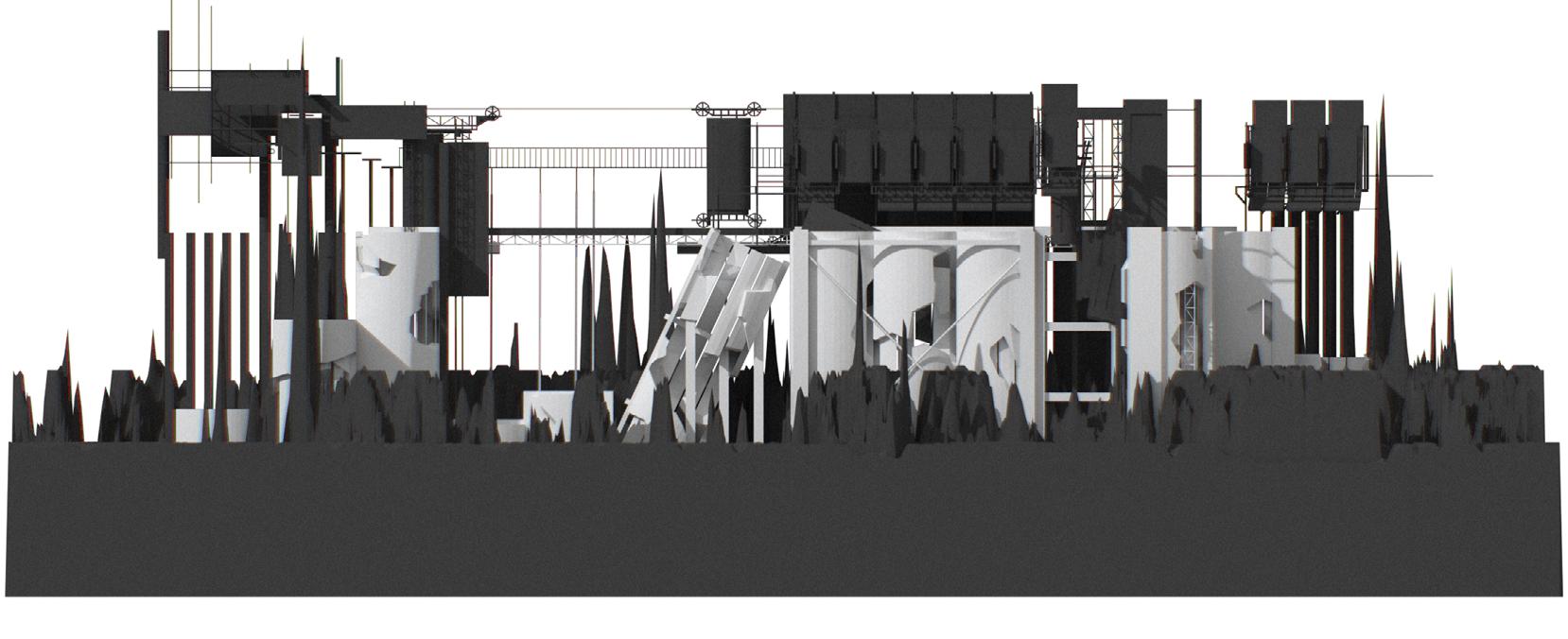

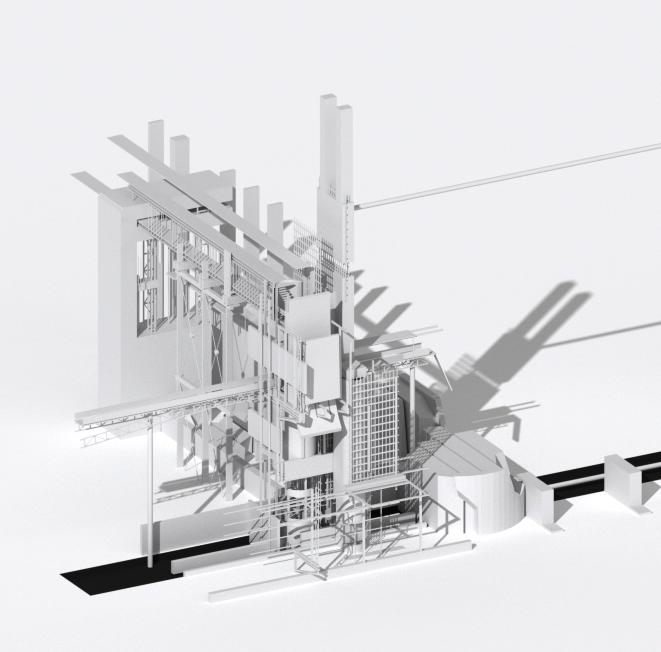

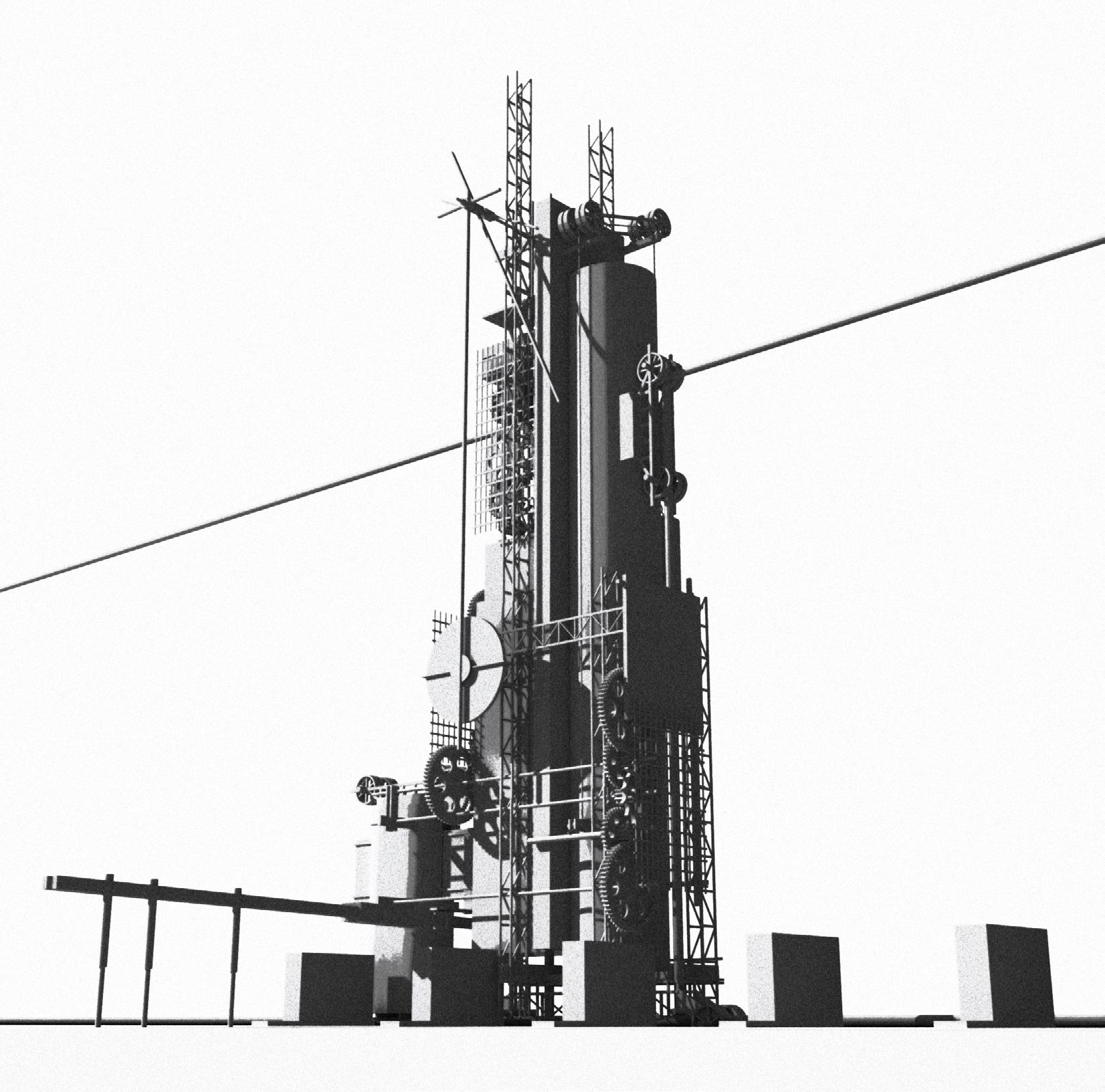

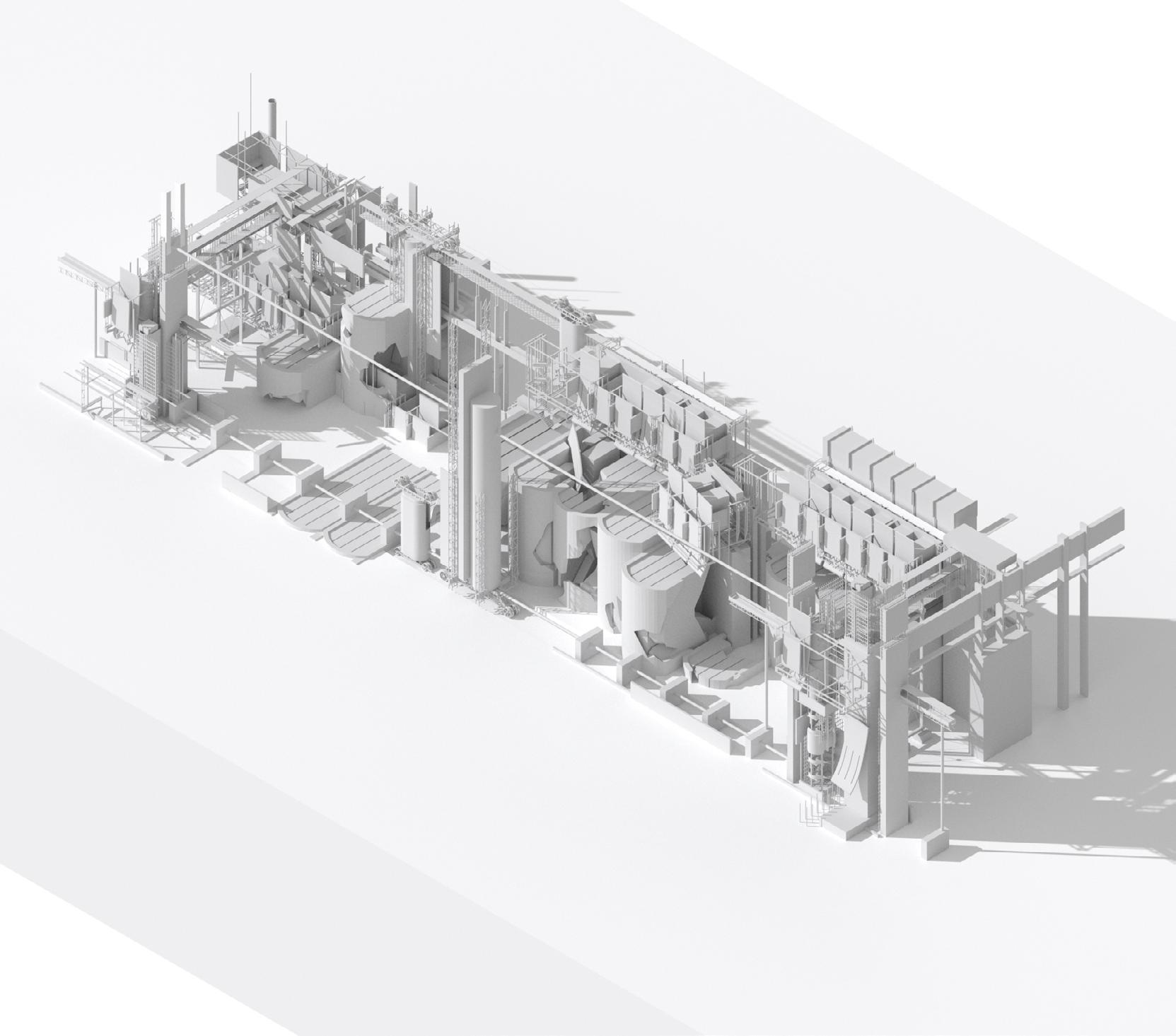

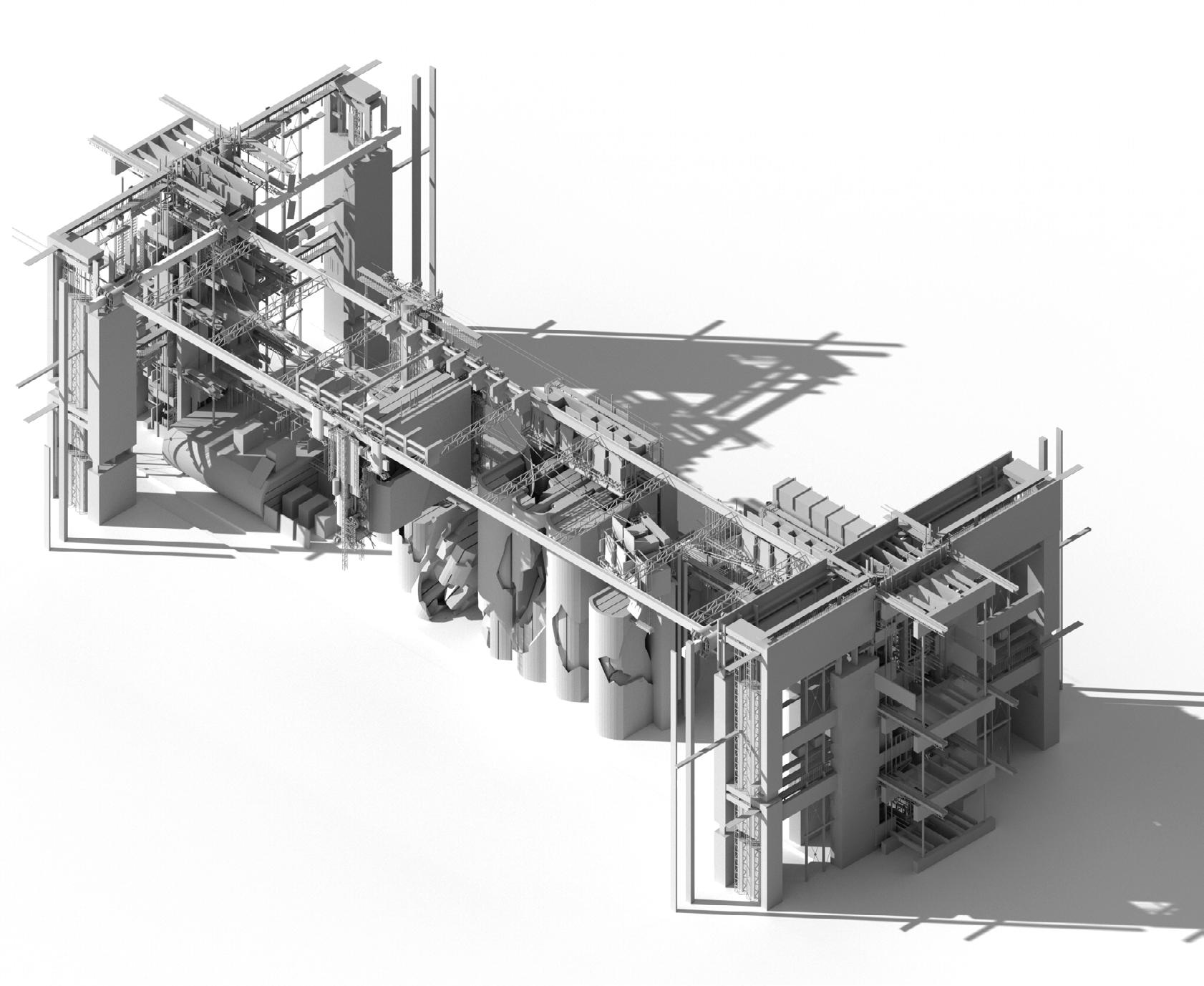

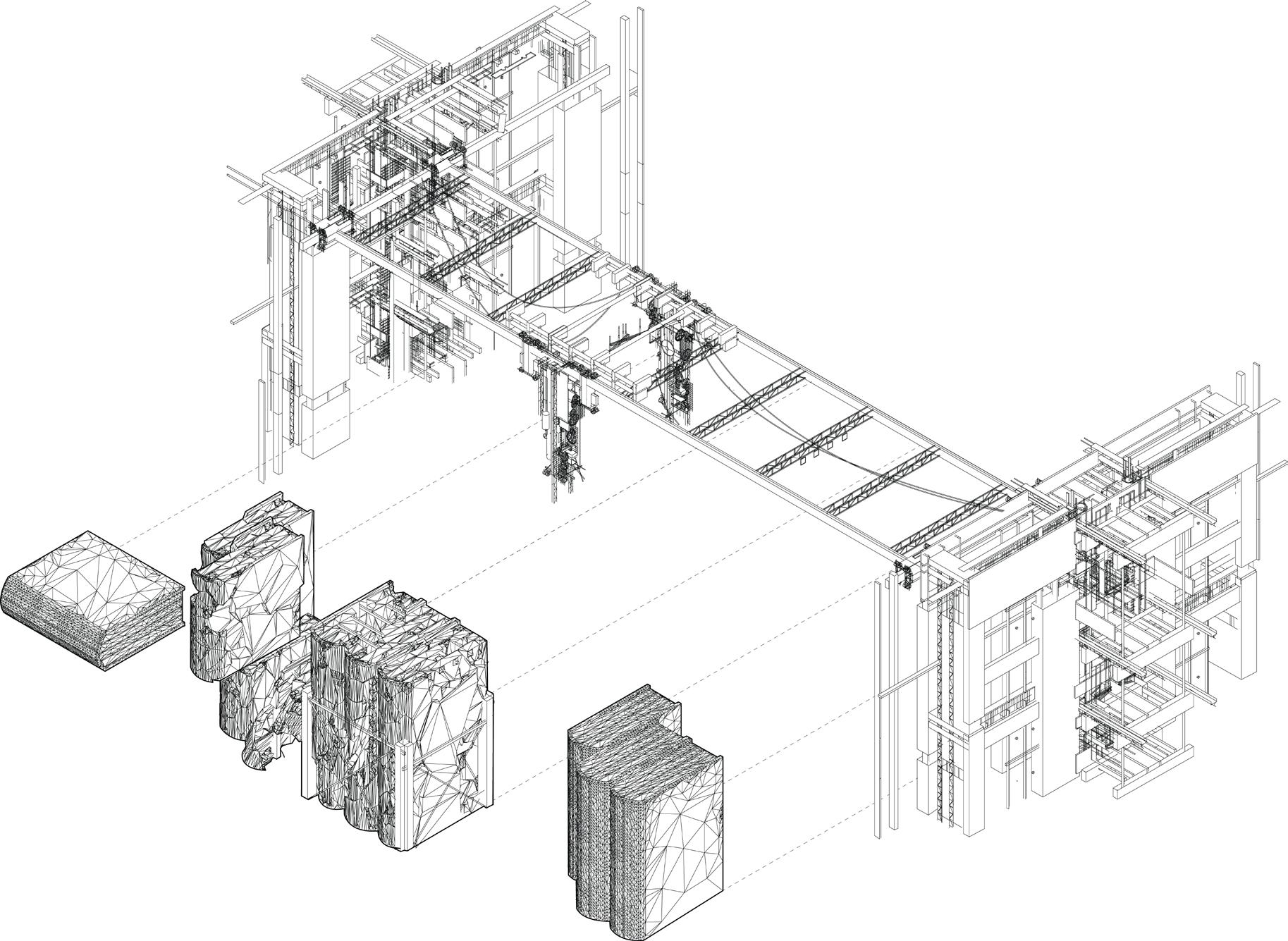

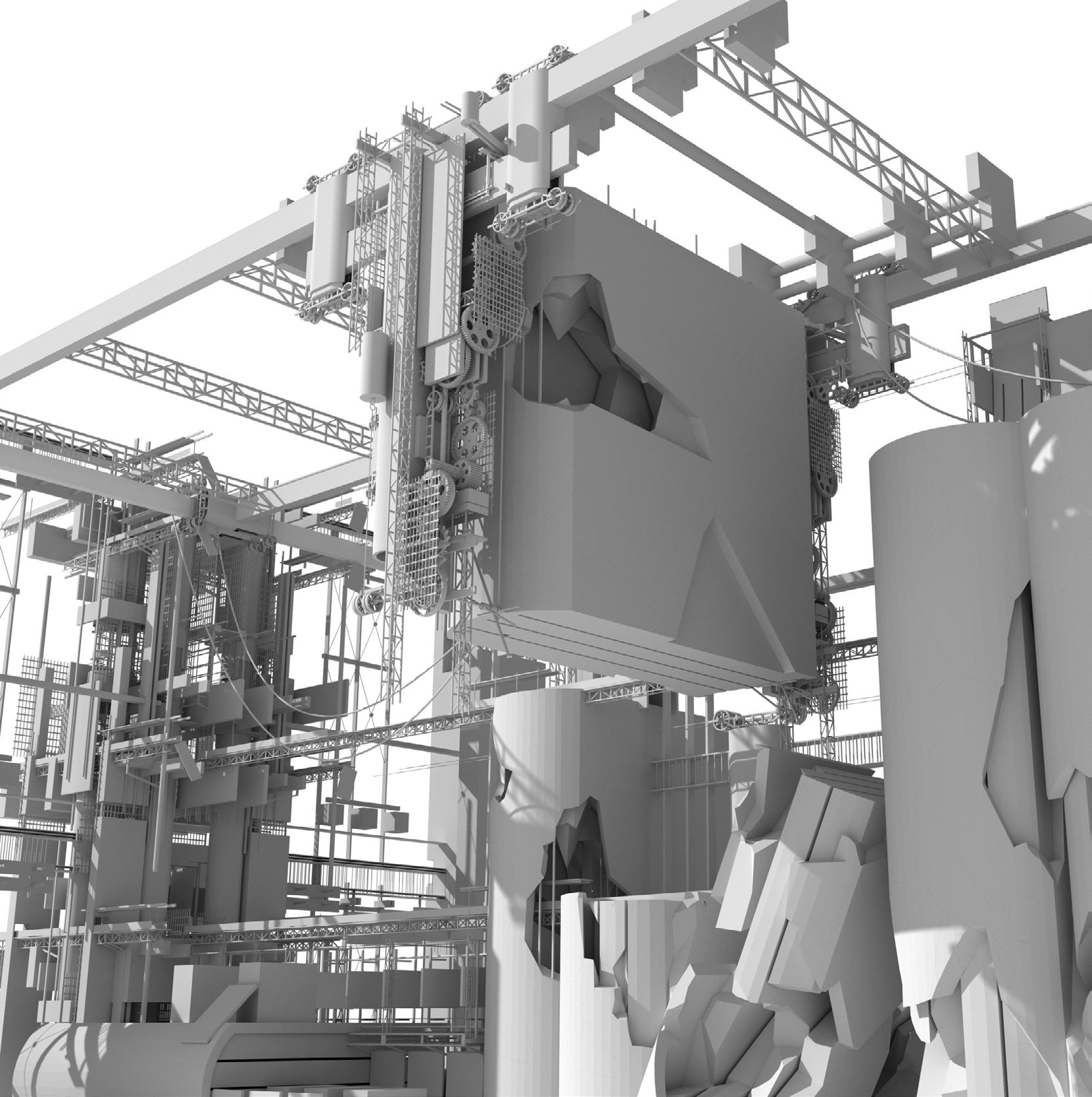

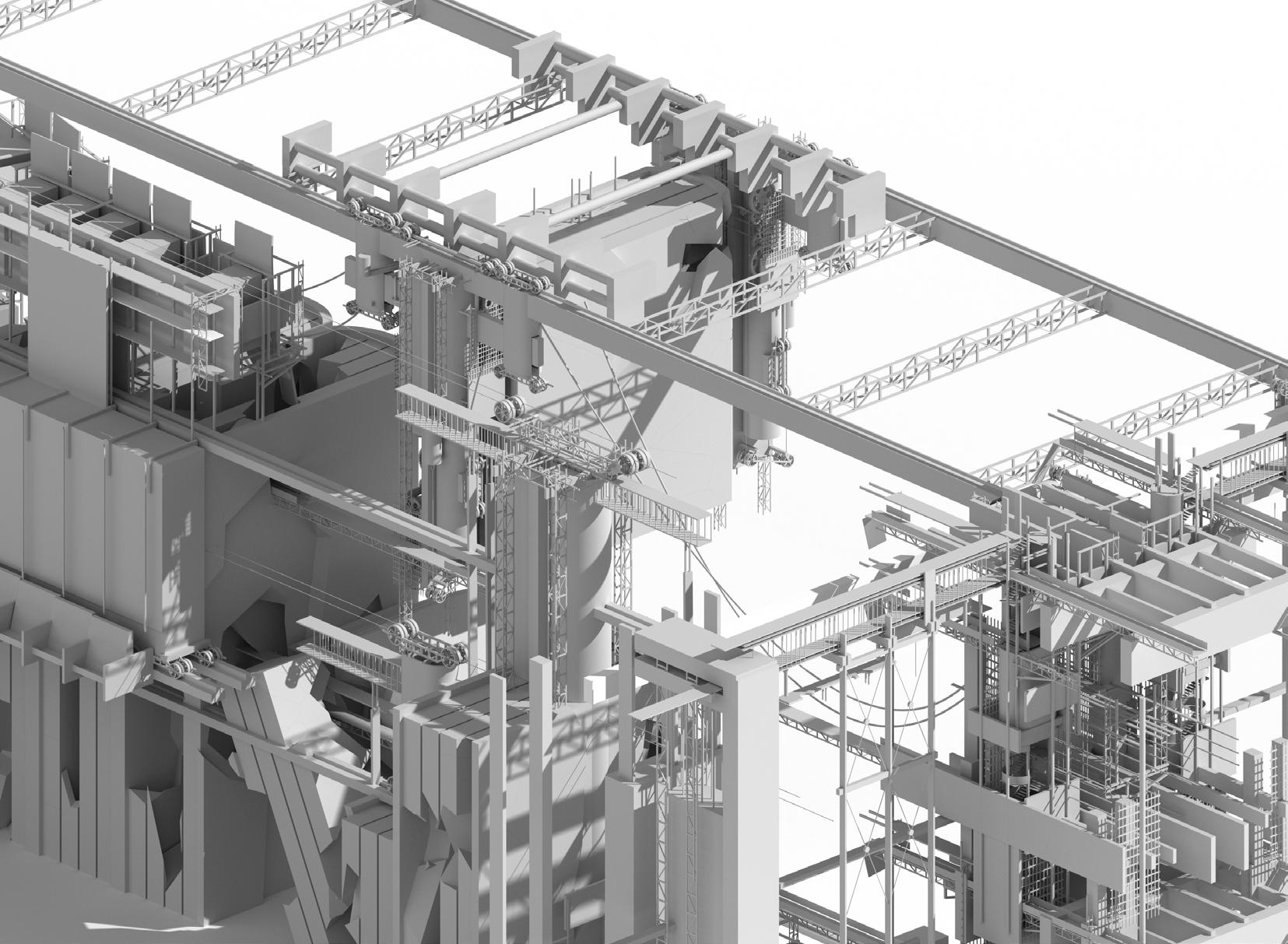

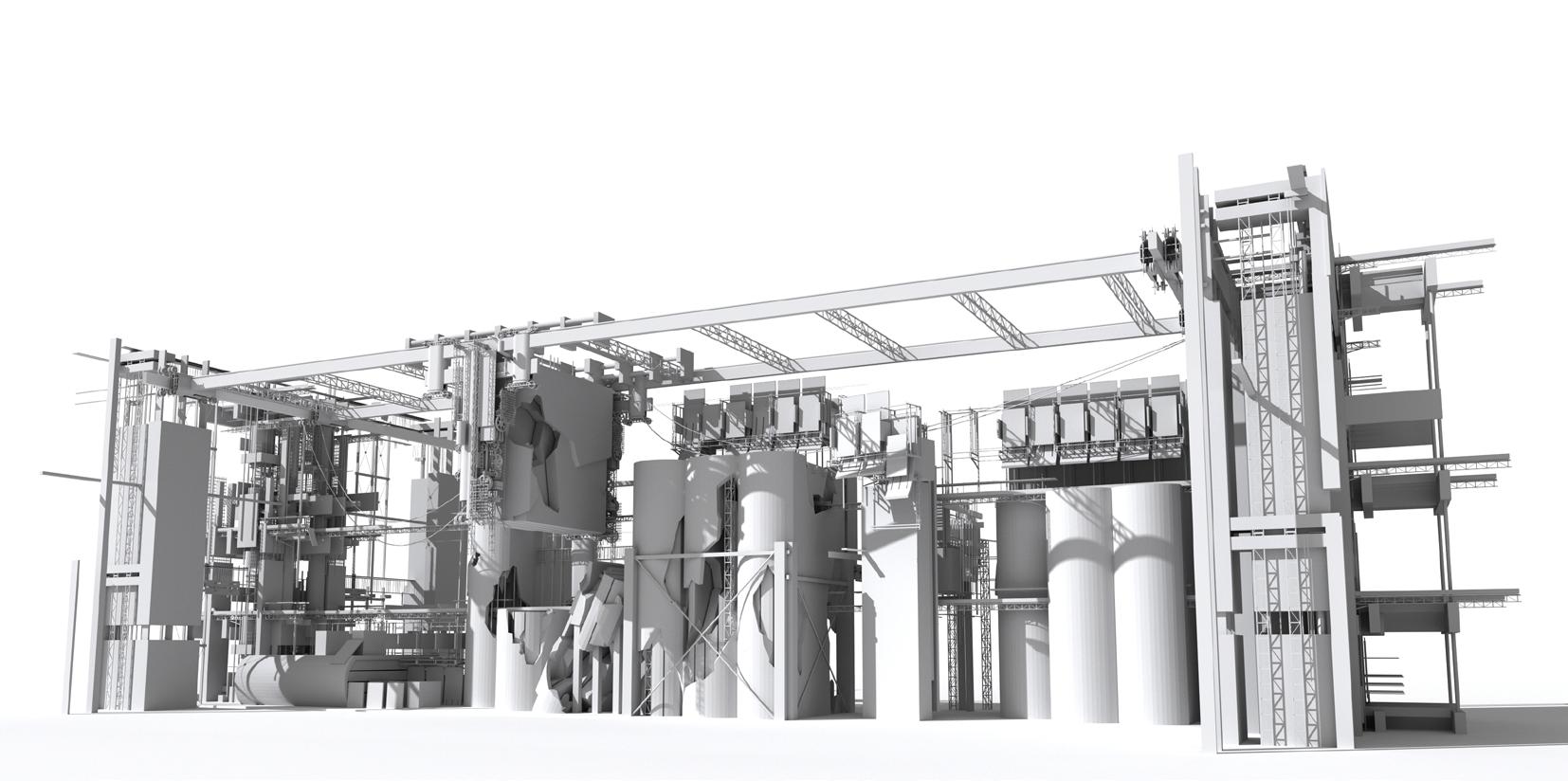

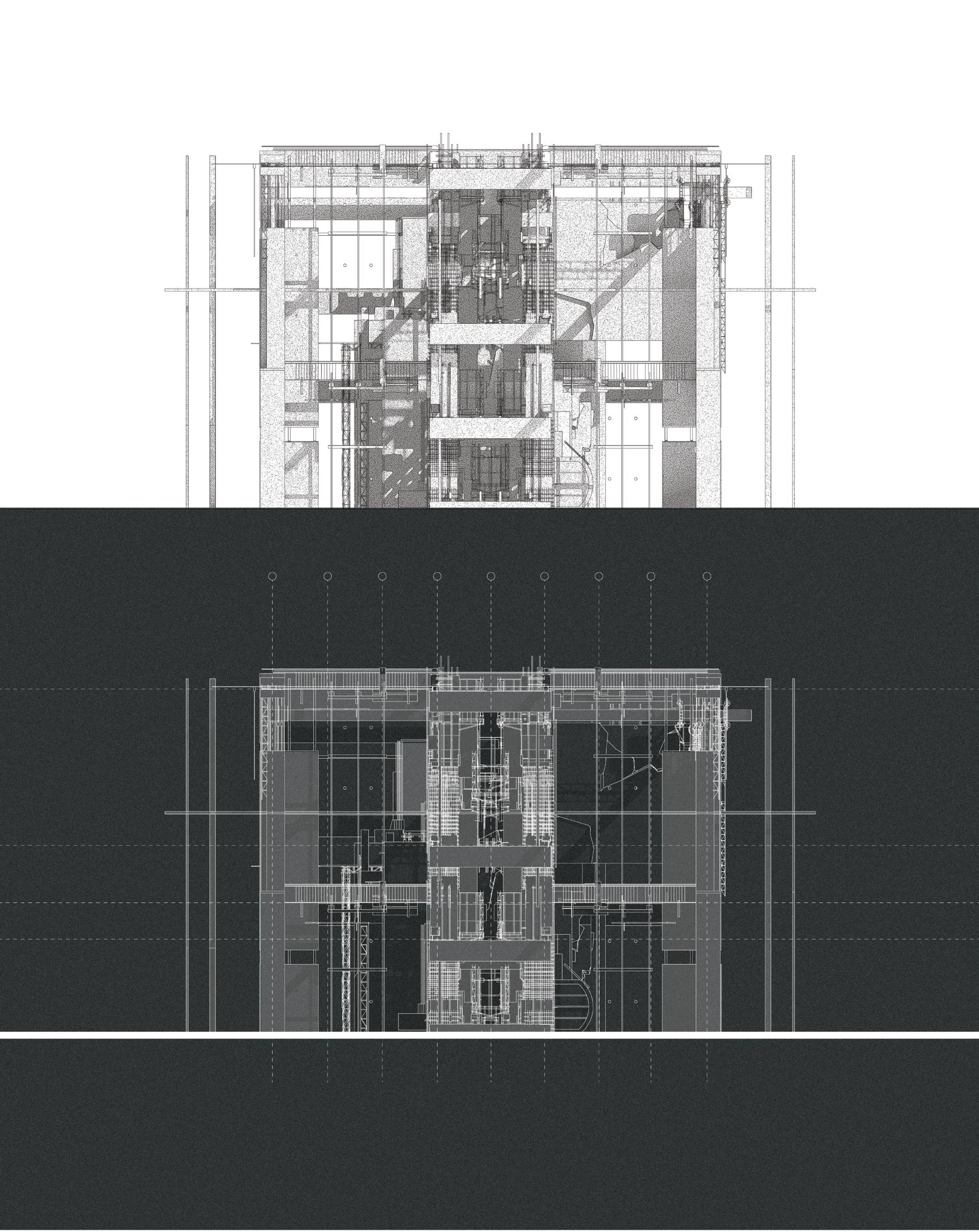

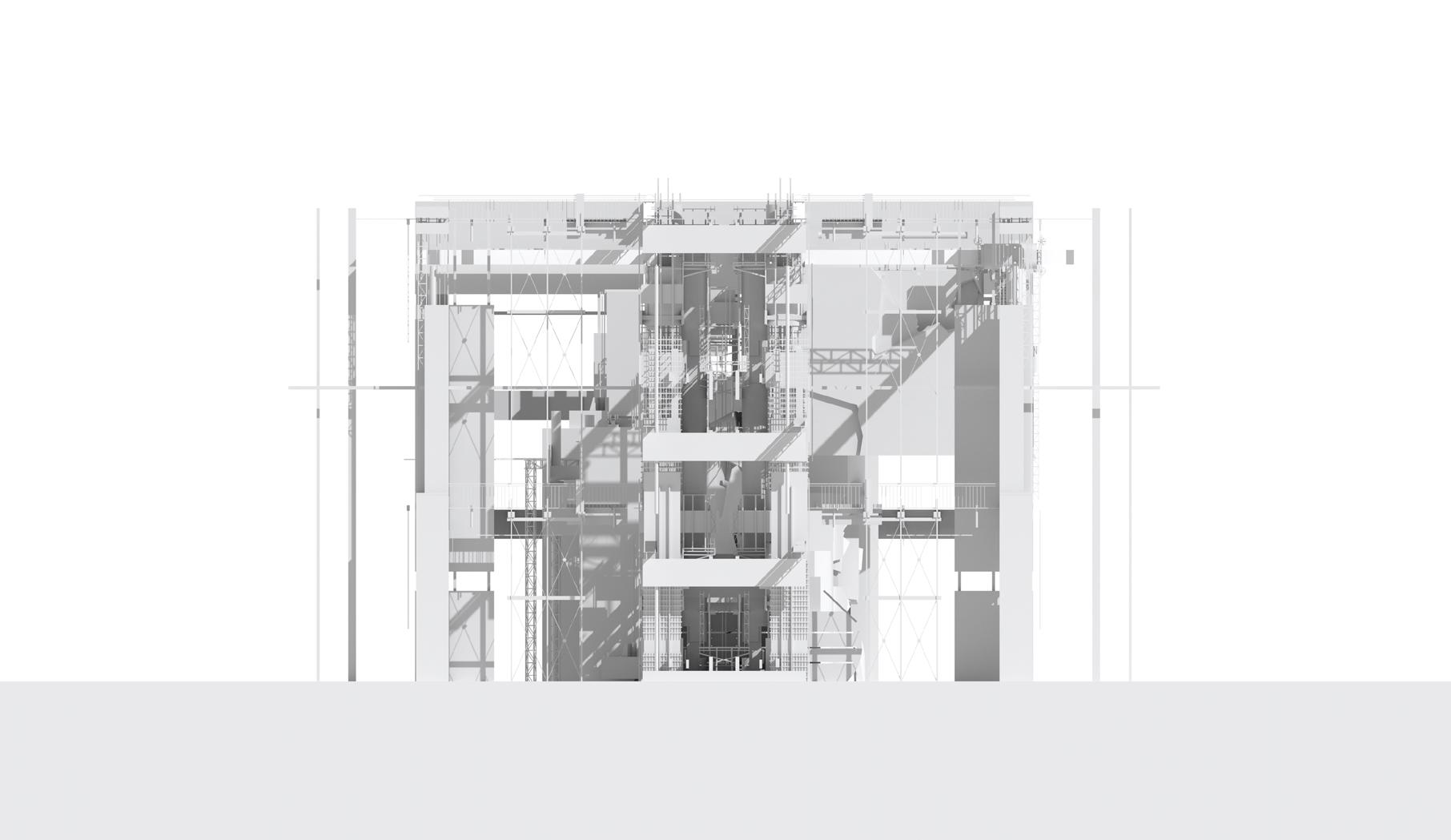

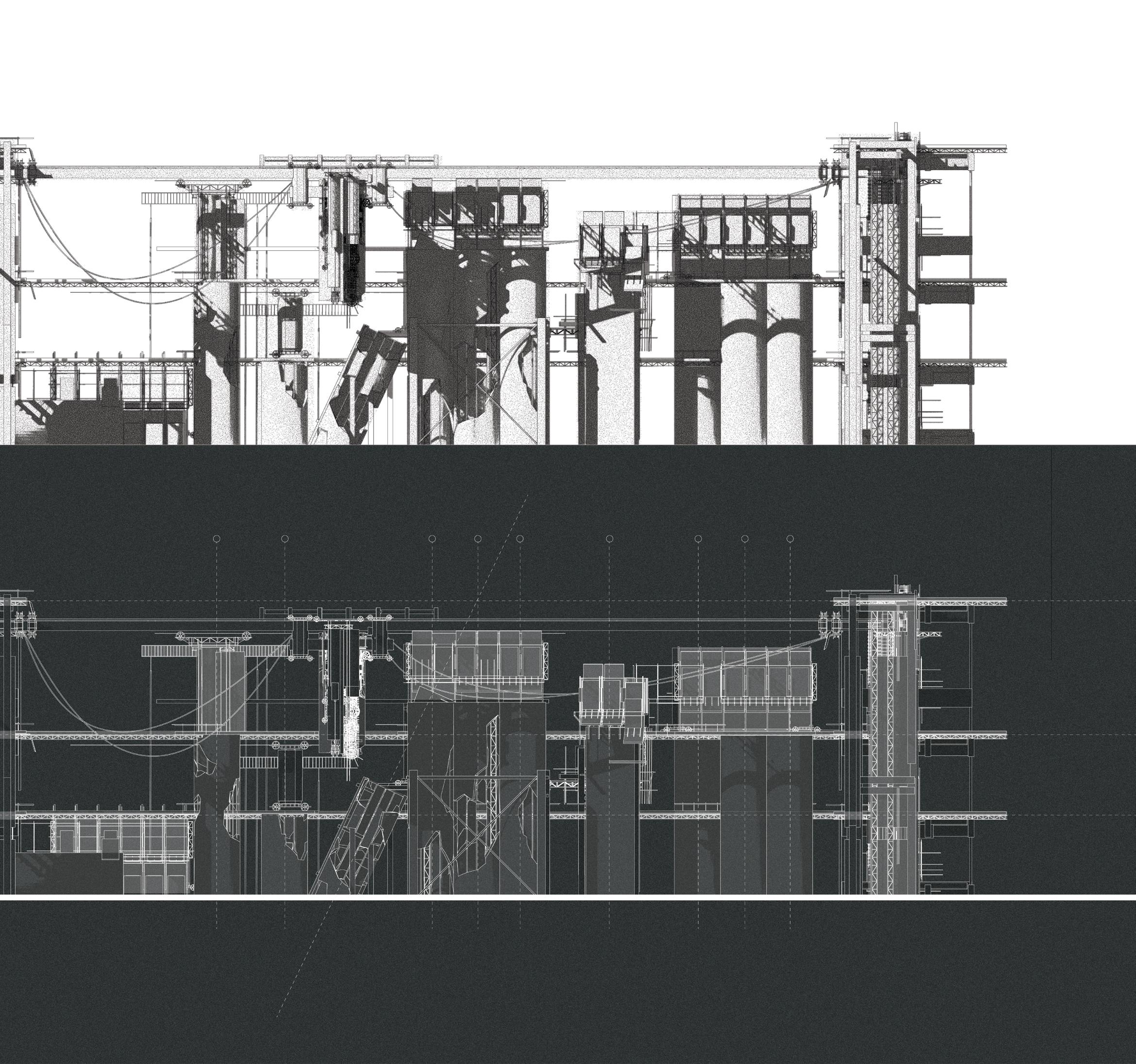

8.2 Experiment One

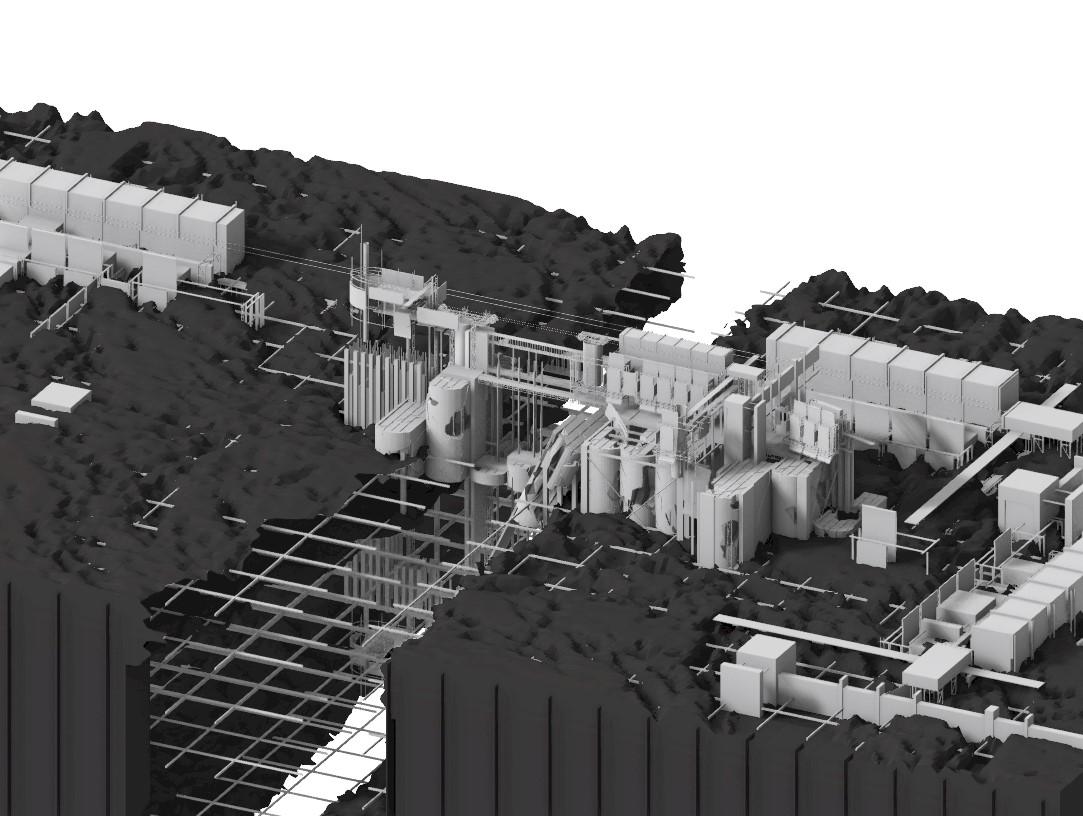

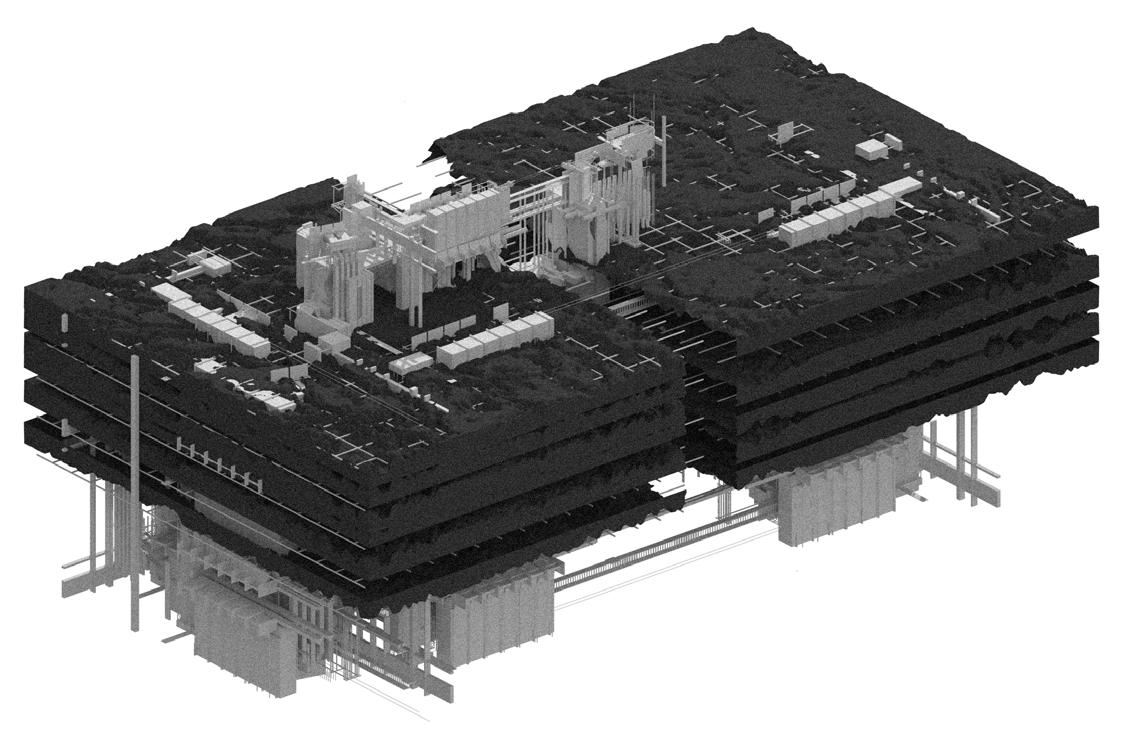

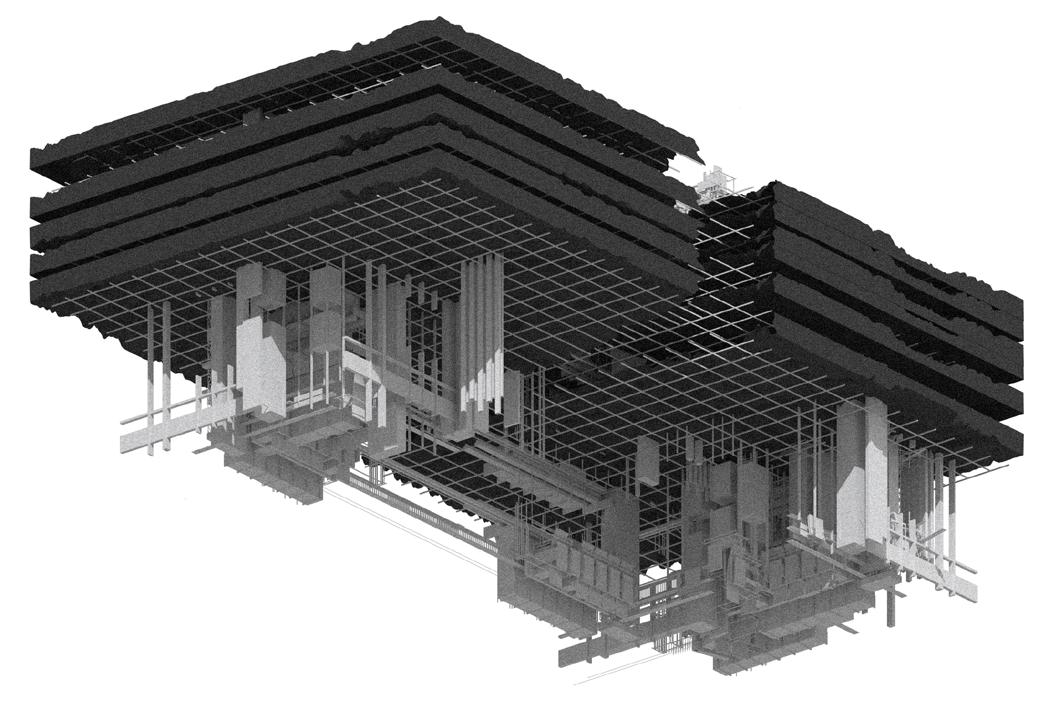

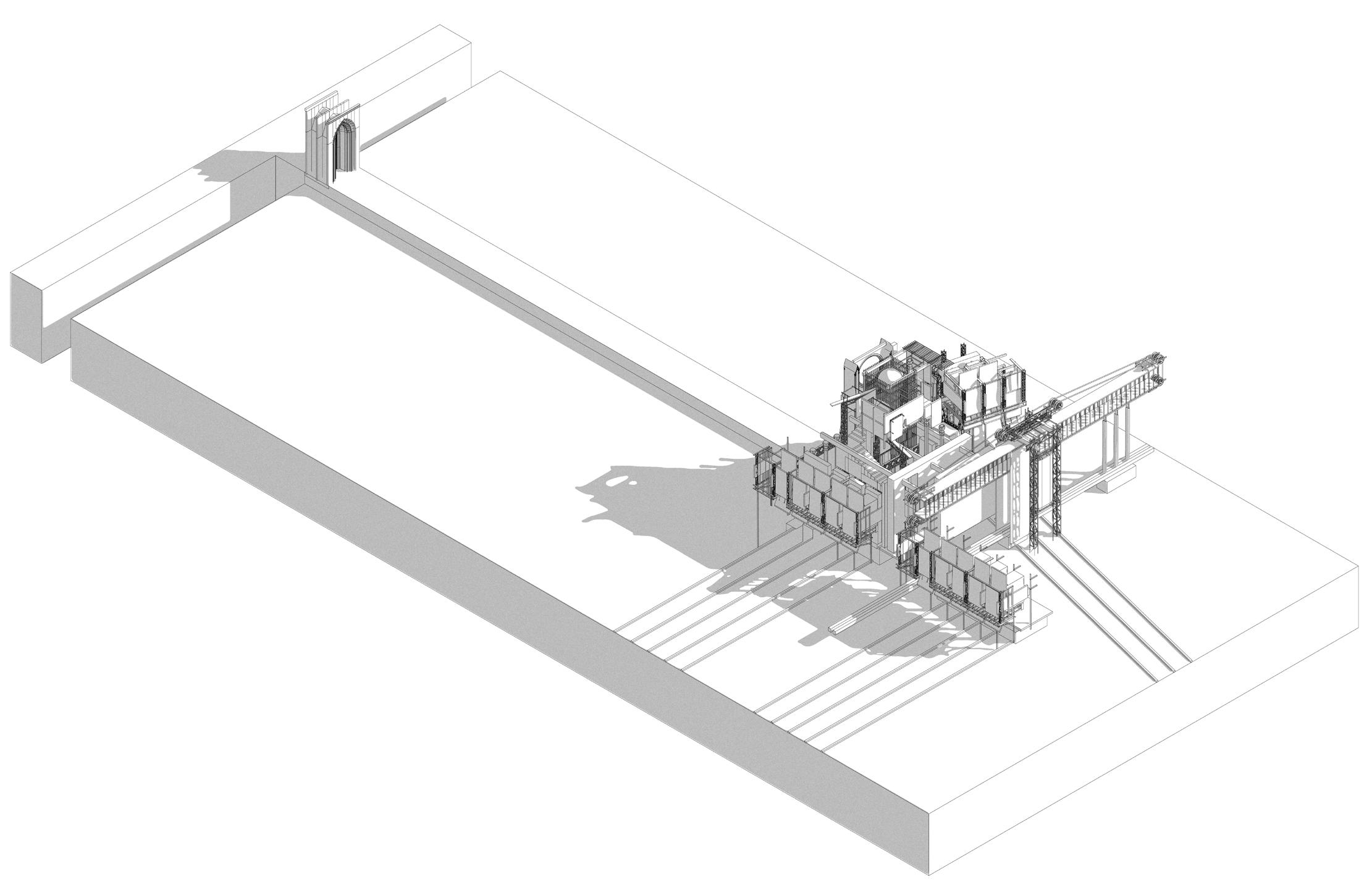

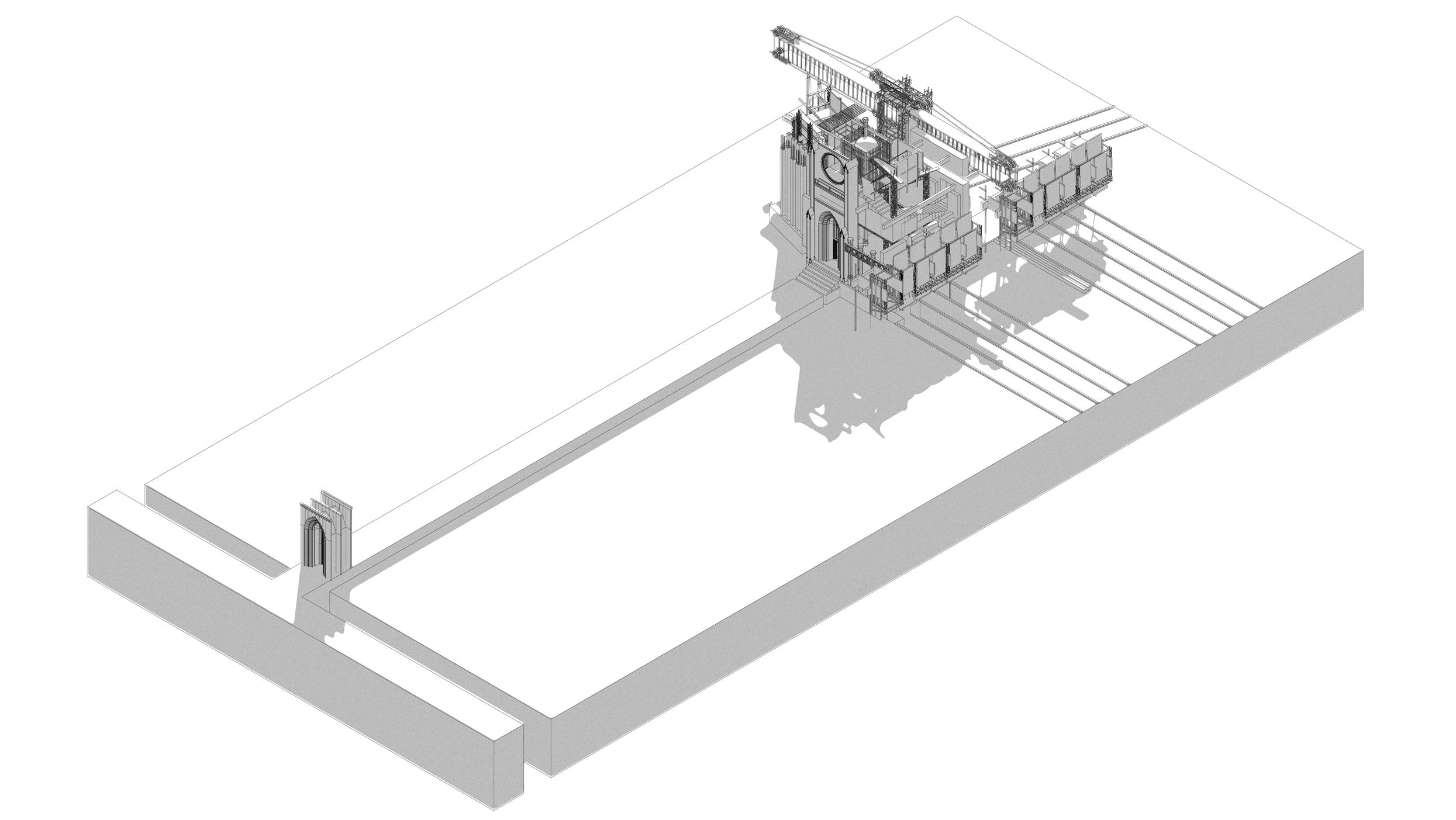

8.3 Experiment Two - The House

8.4 Critical Reflection

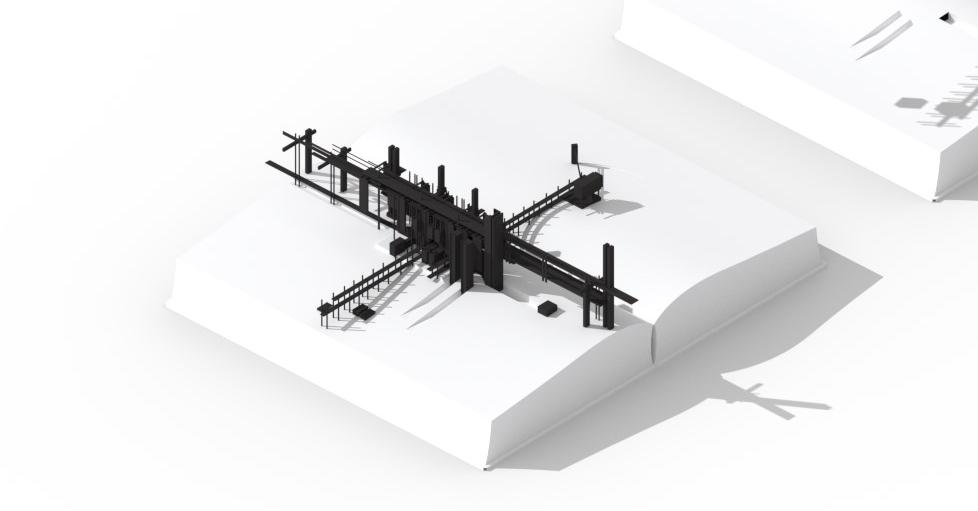

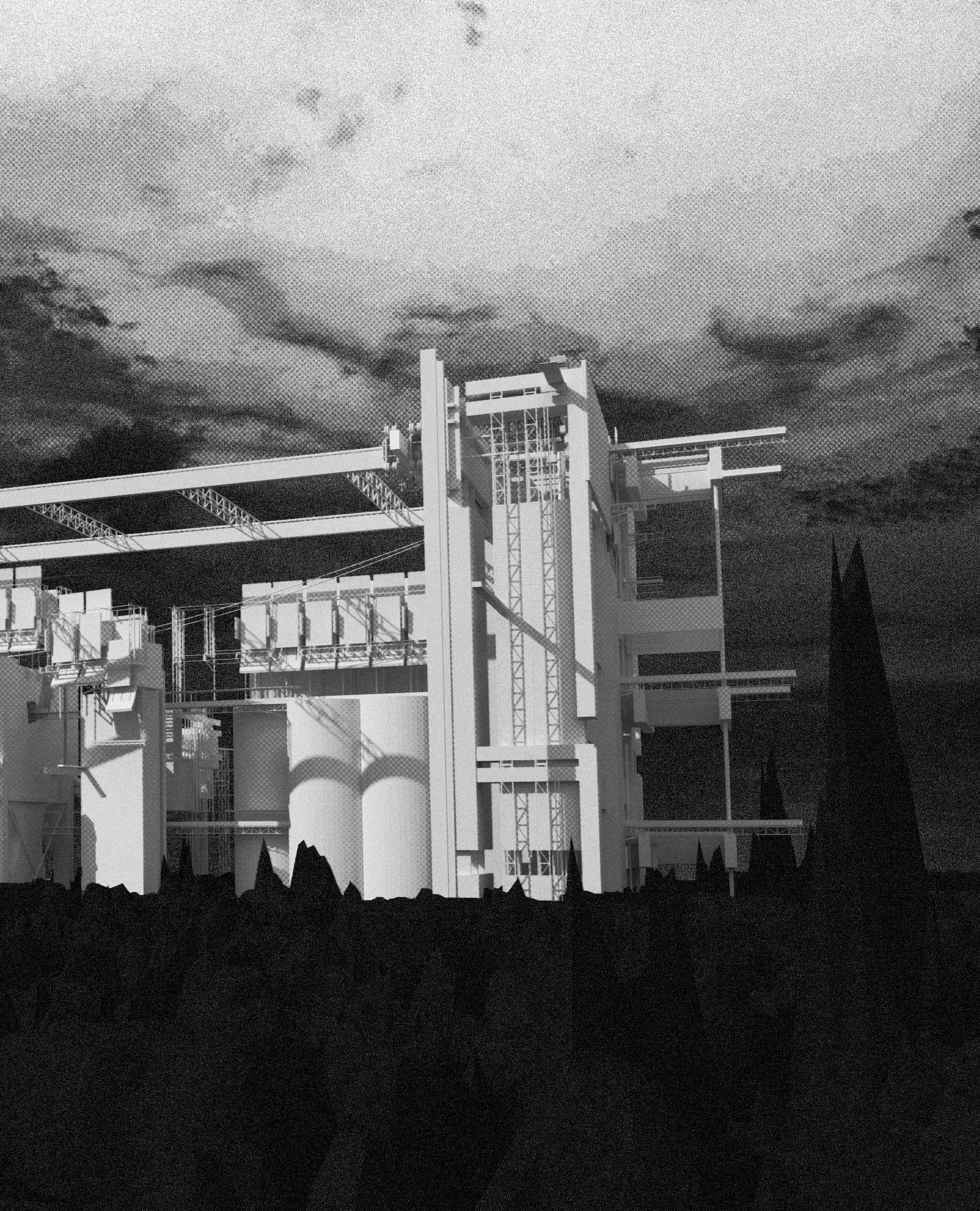

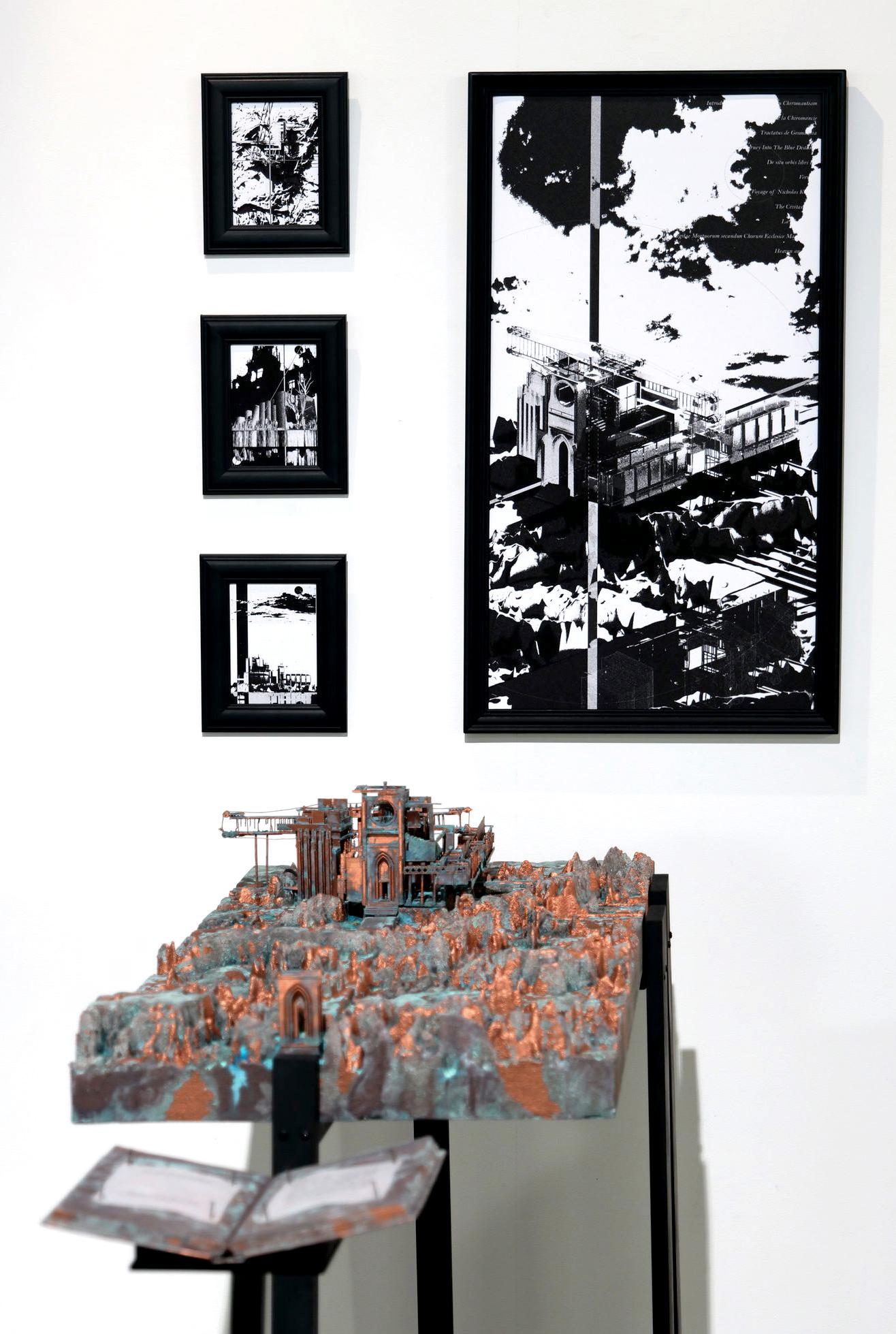

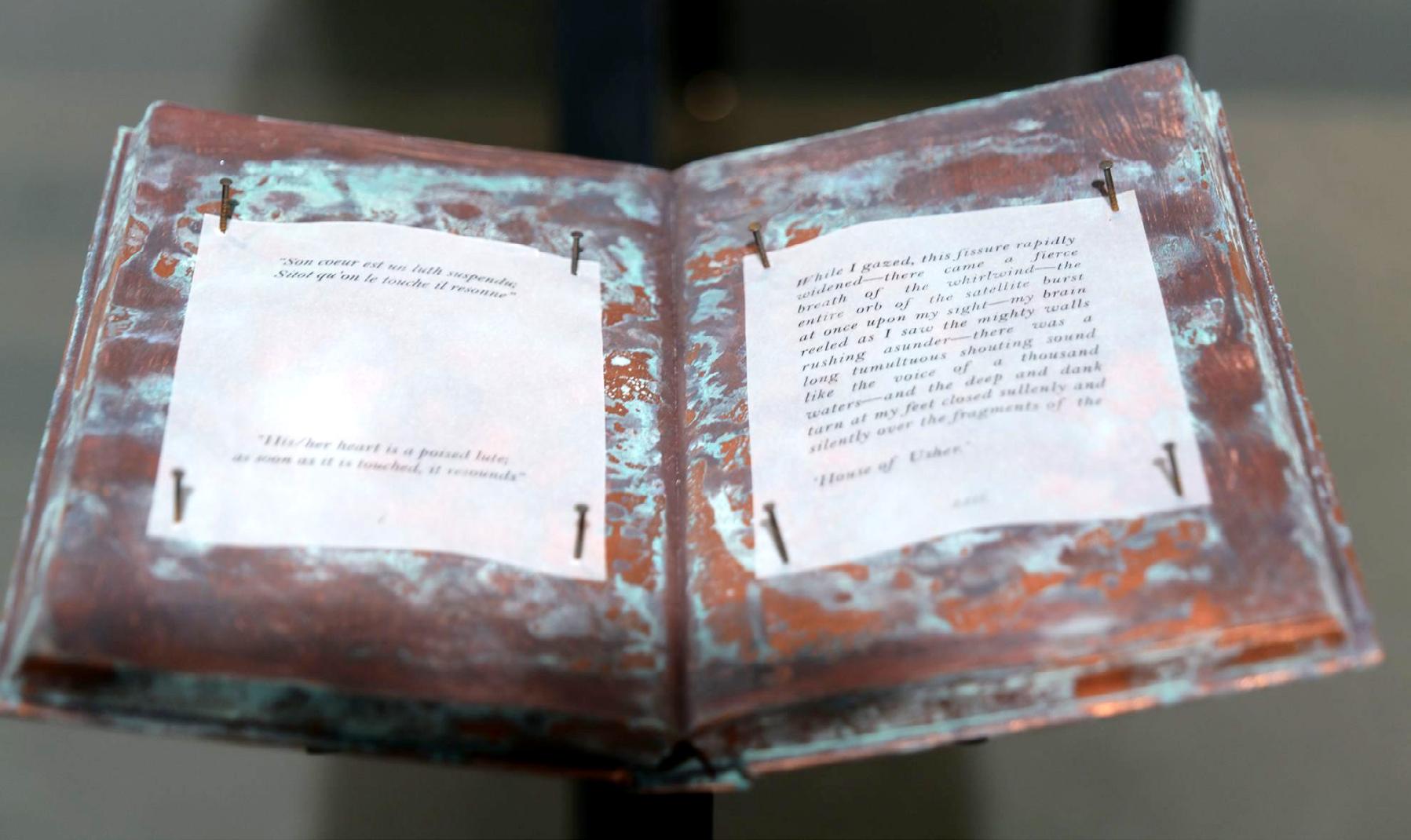

9.0 EXHIBITION

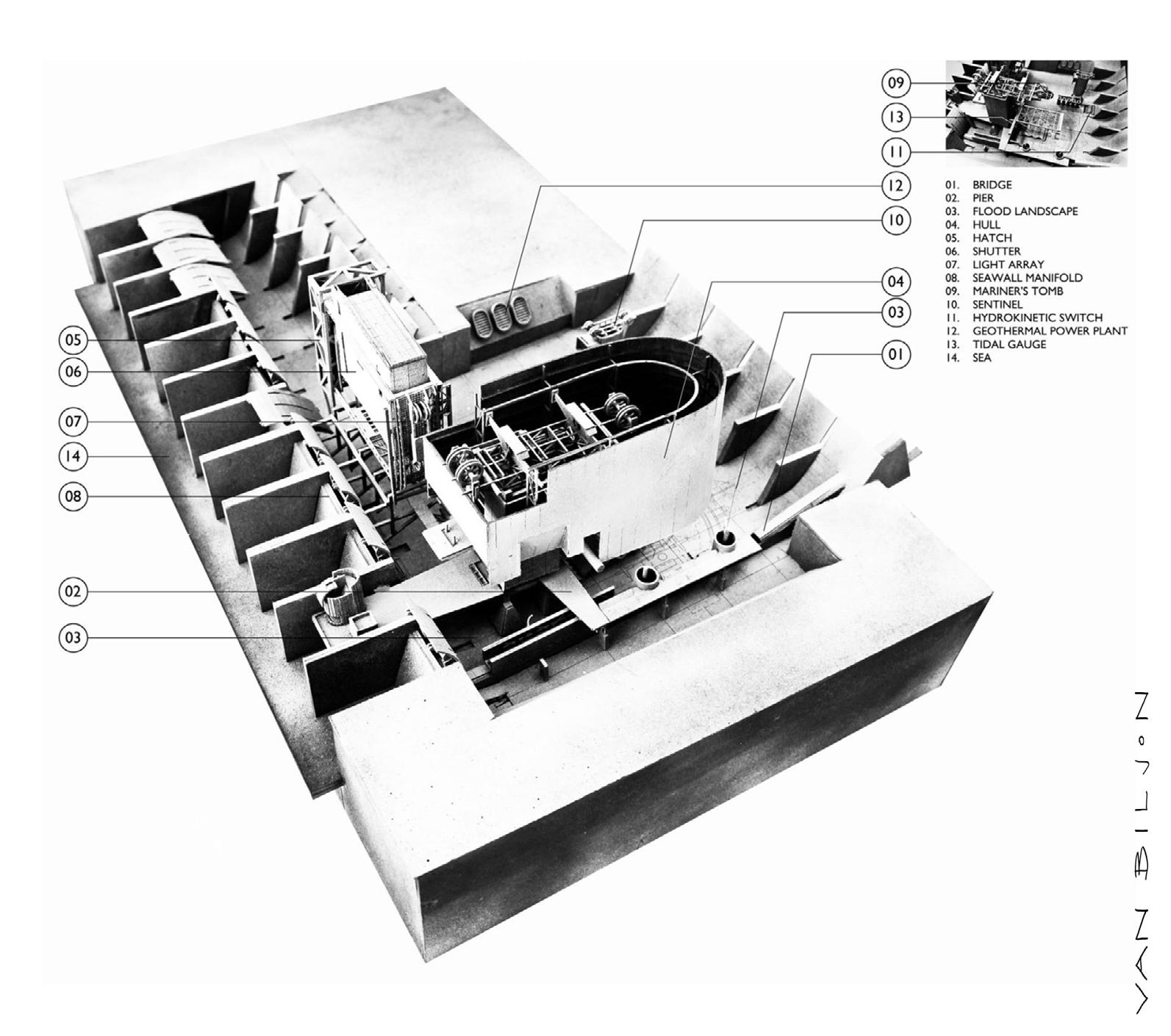

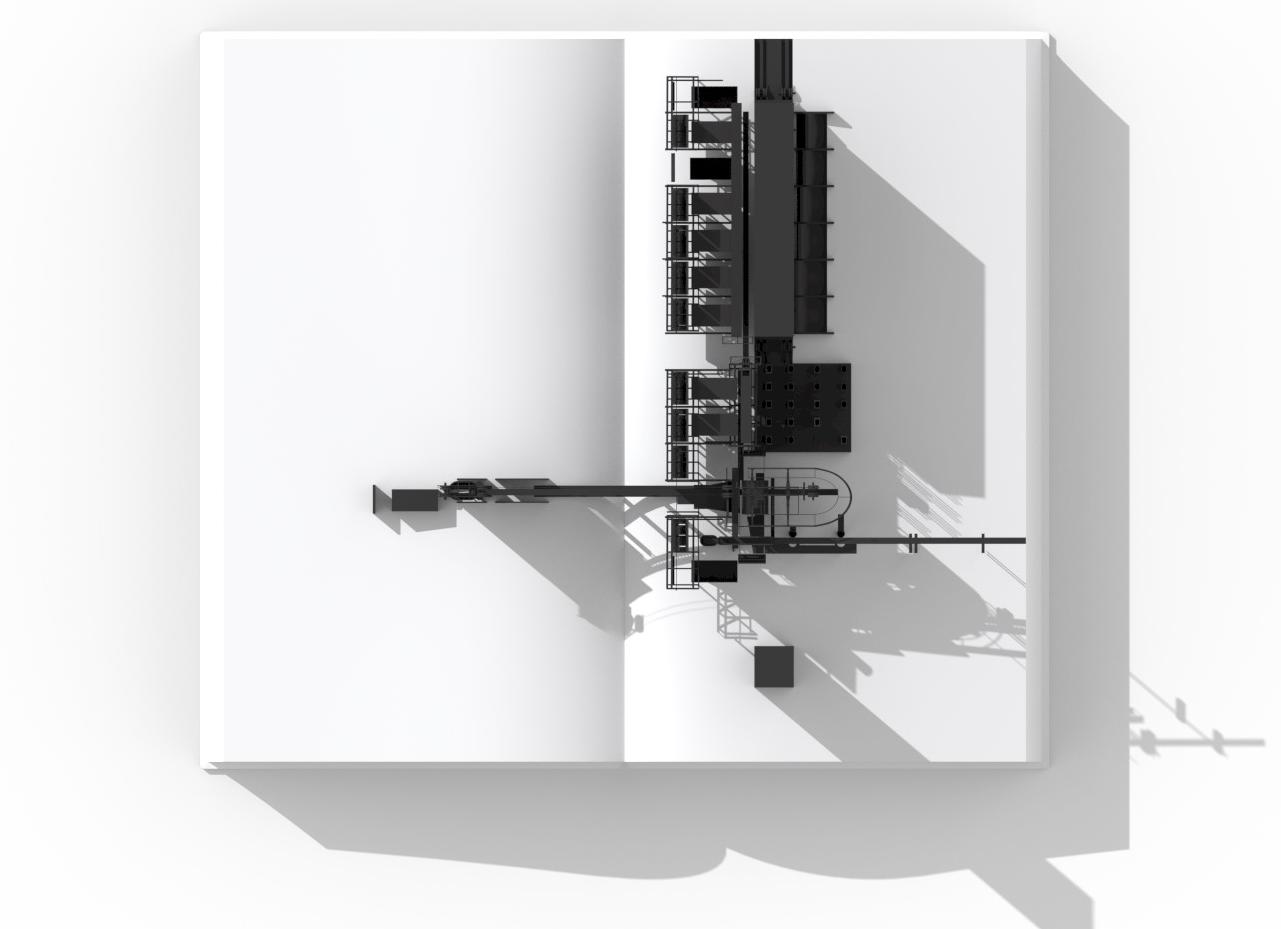

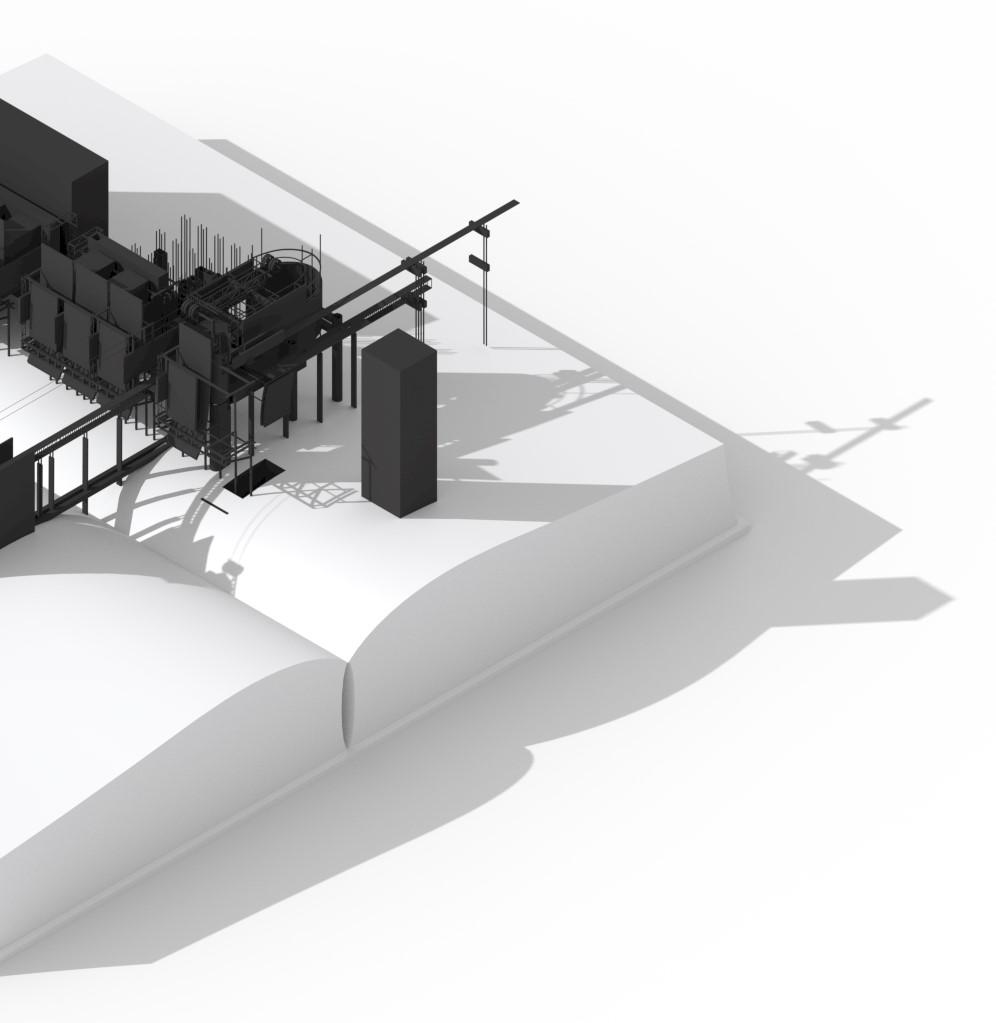

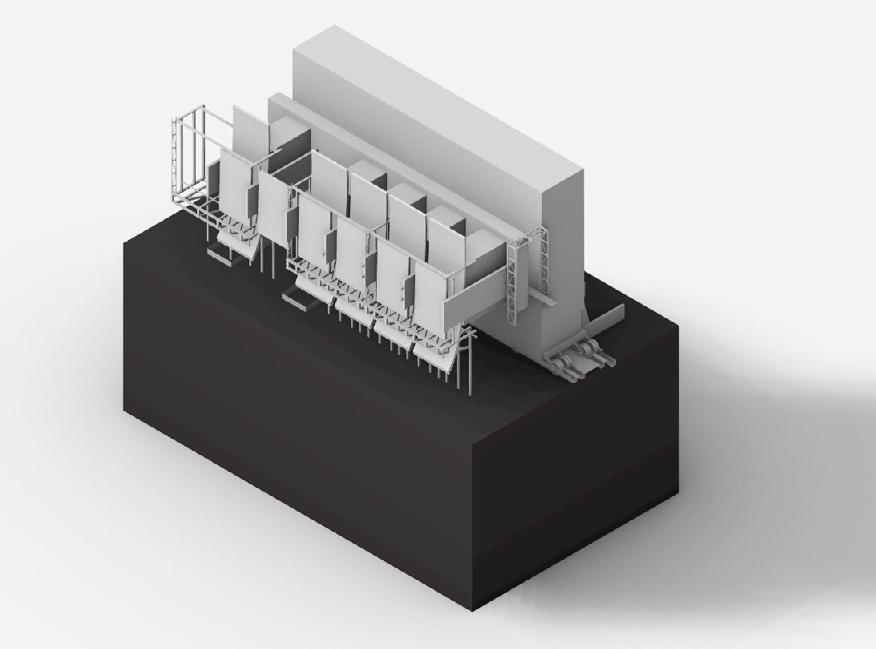

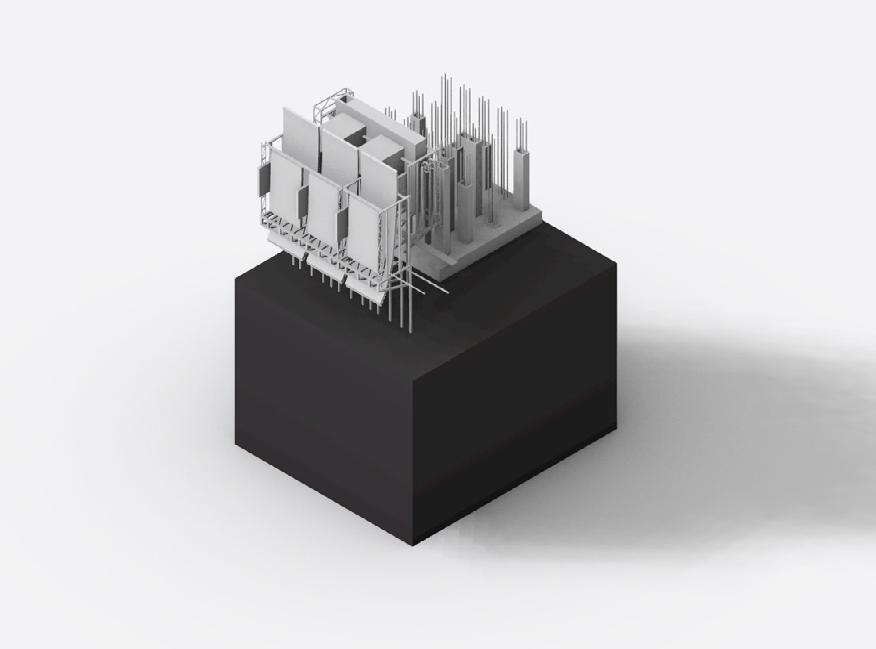

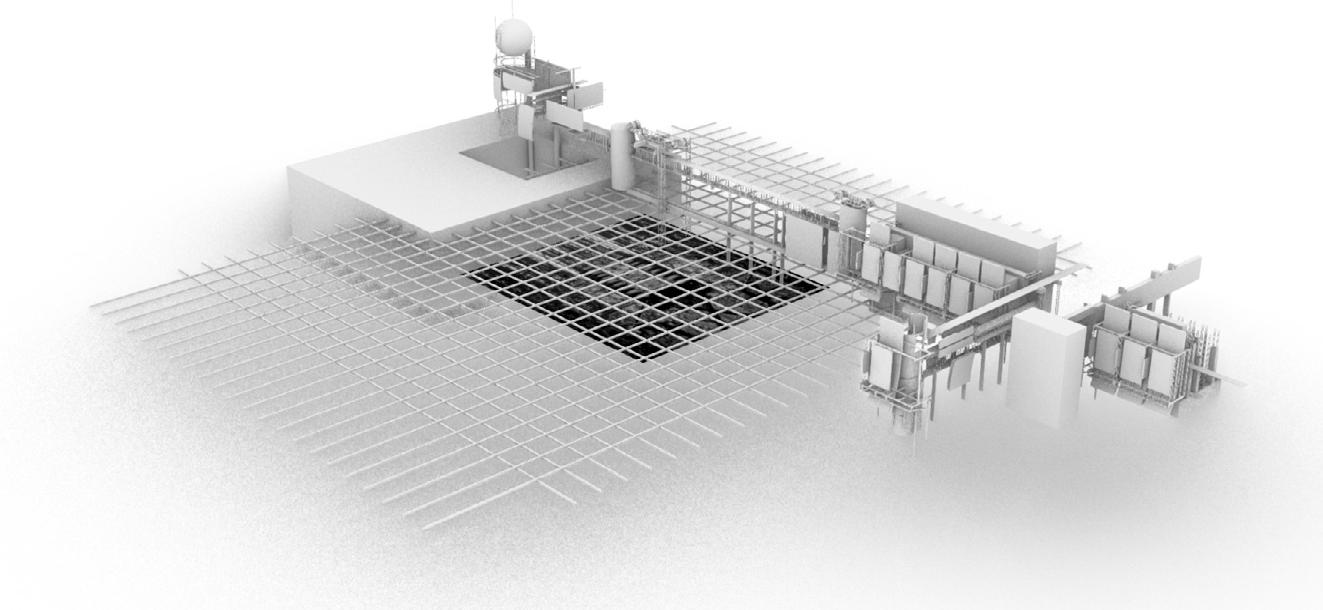

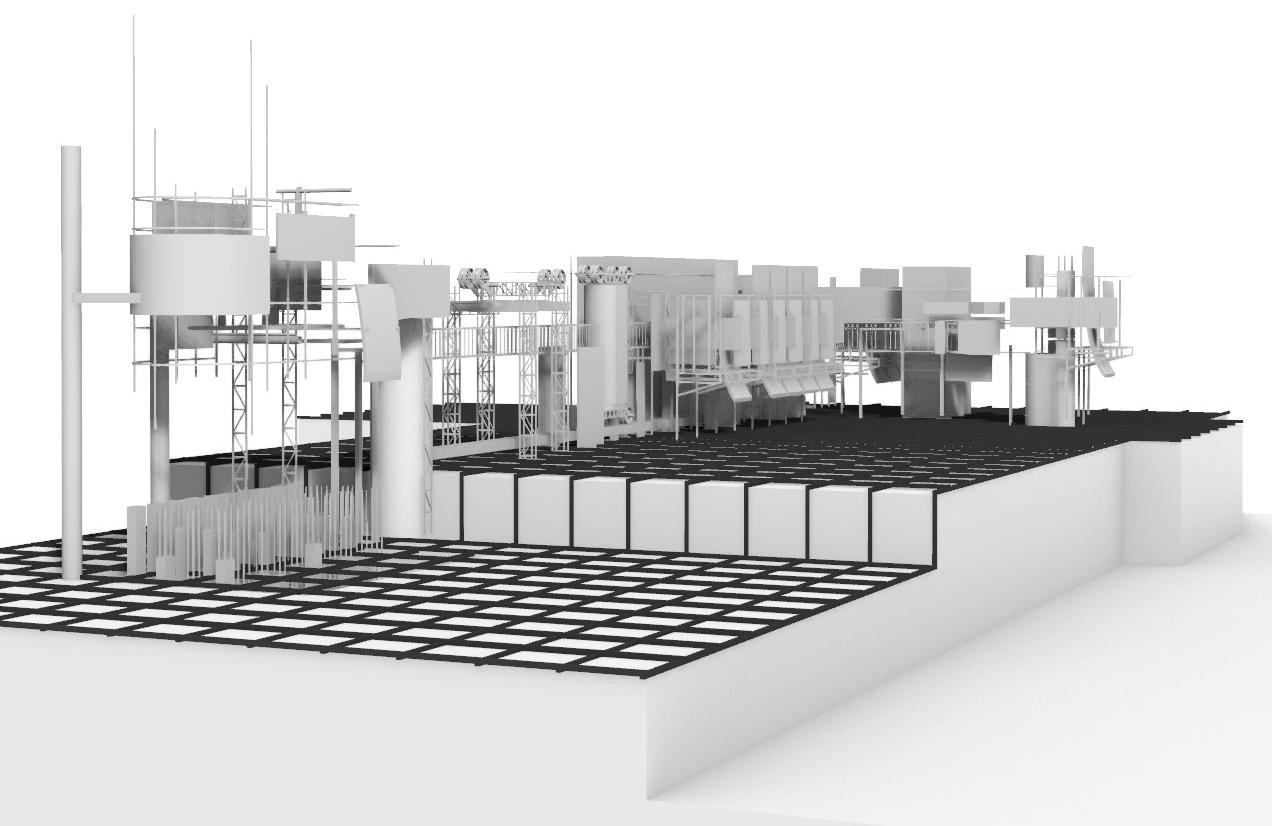

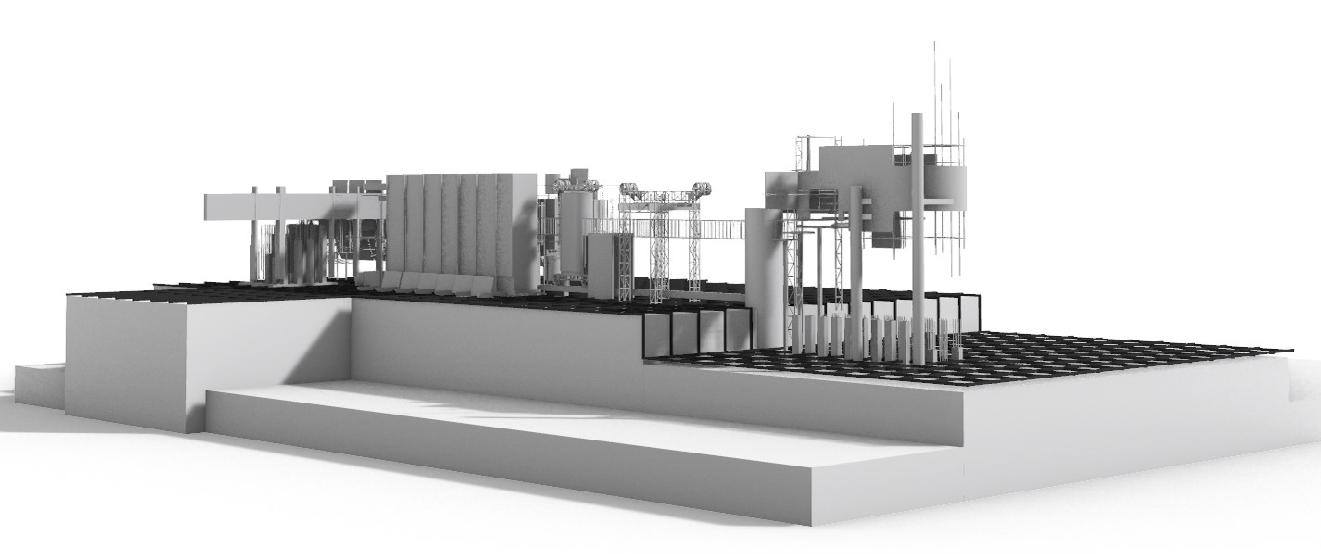

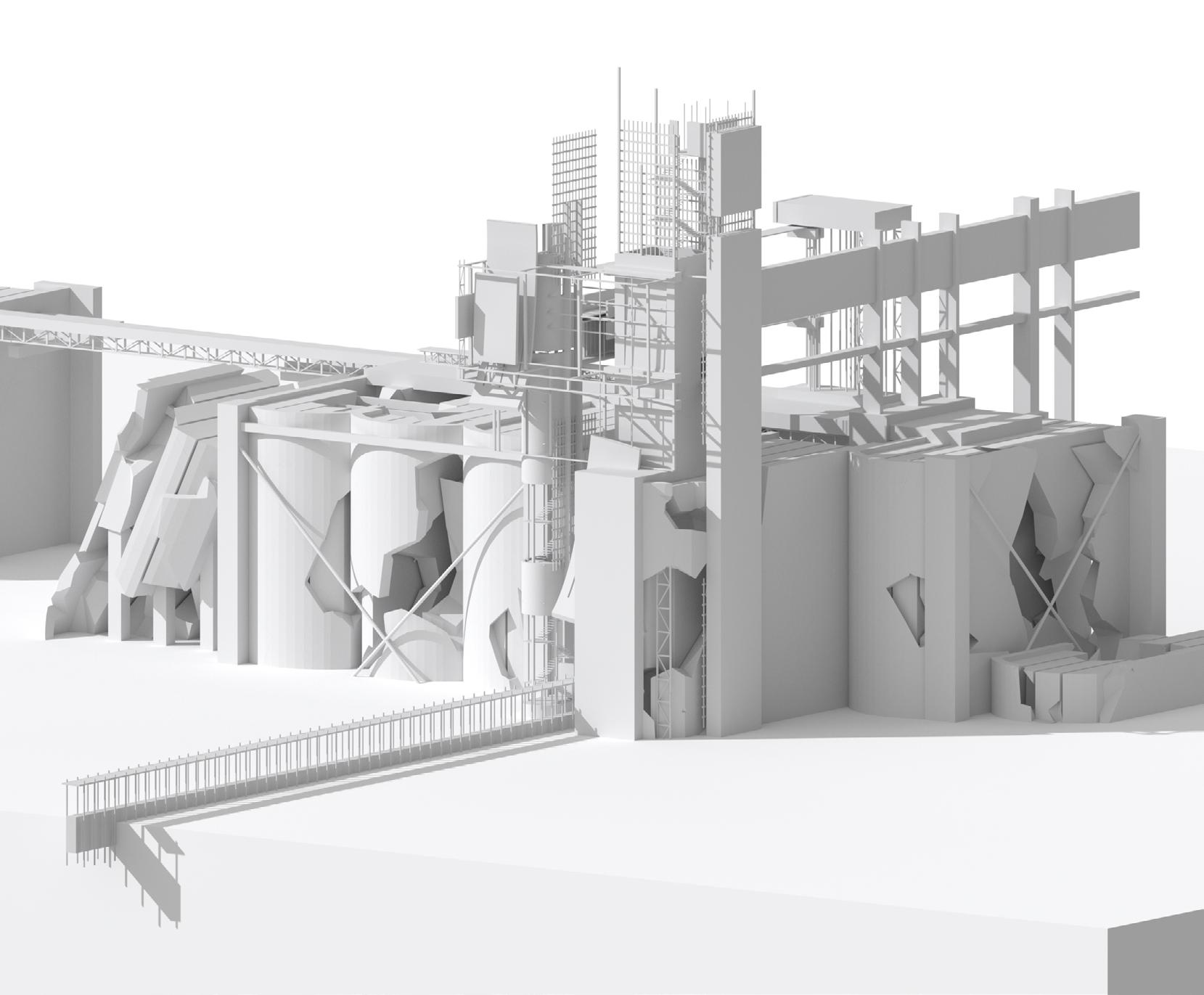

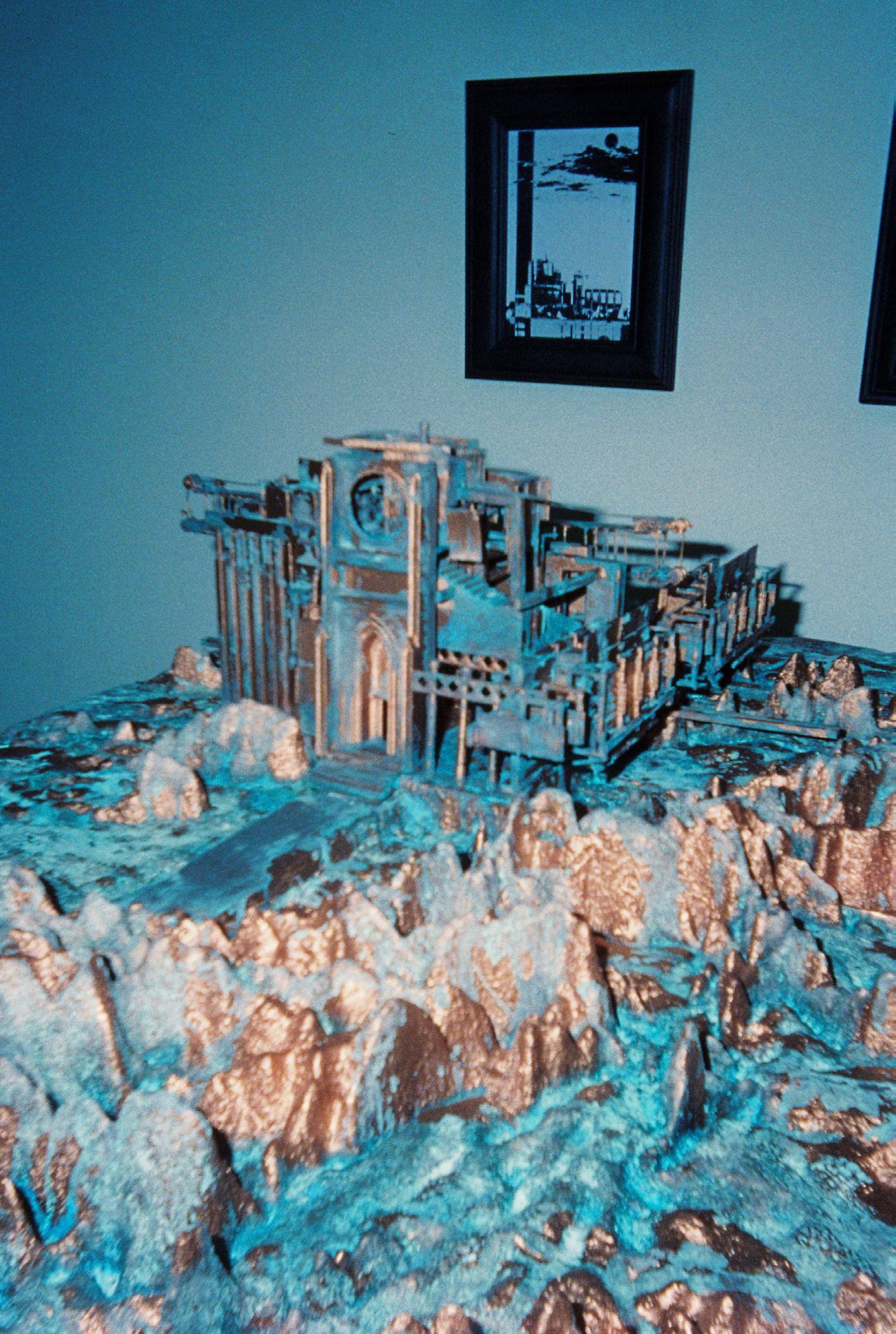

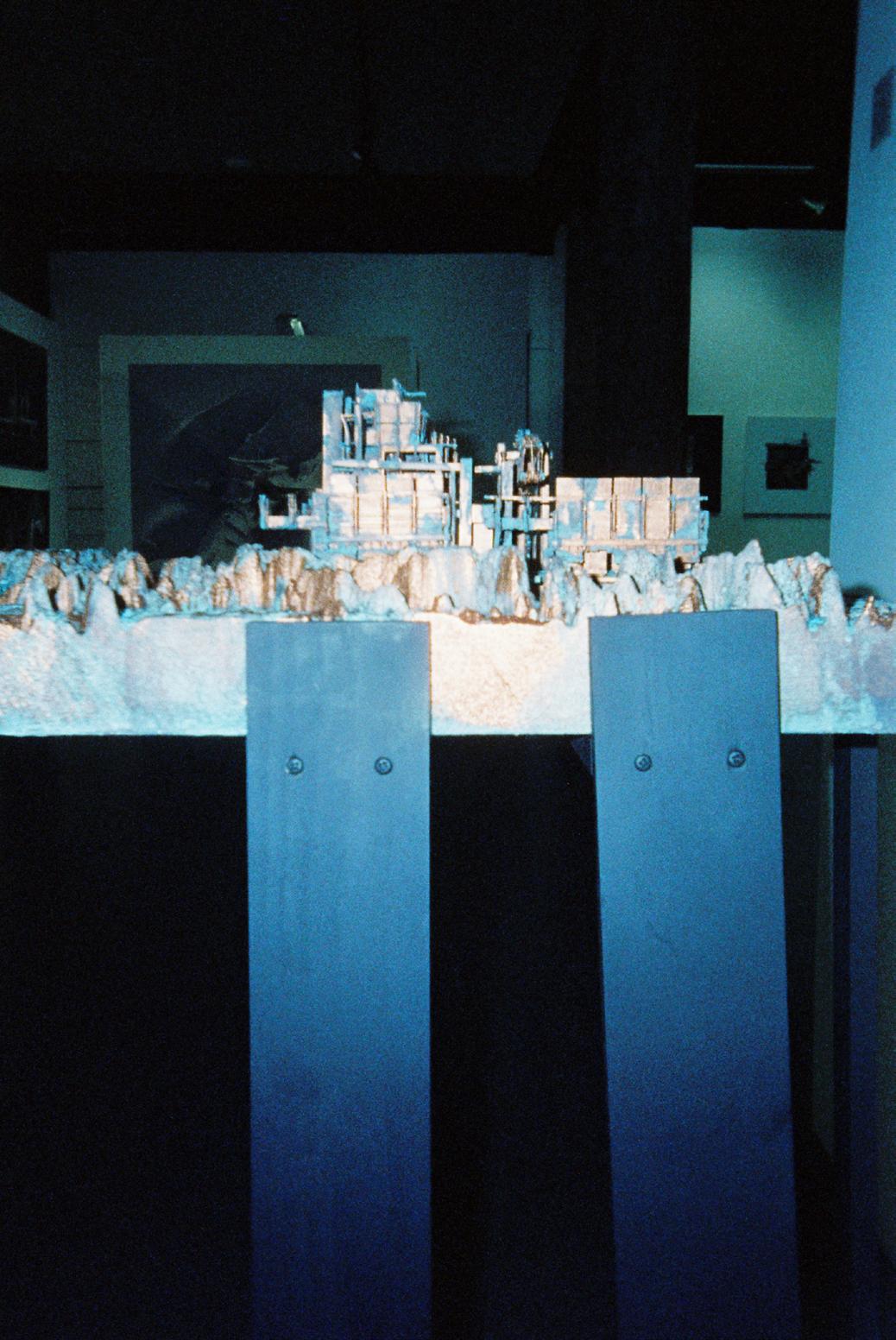

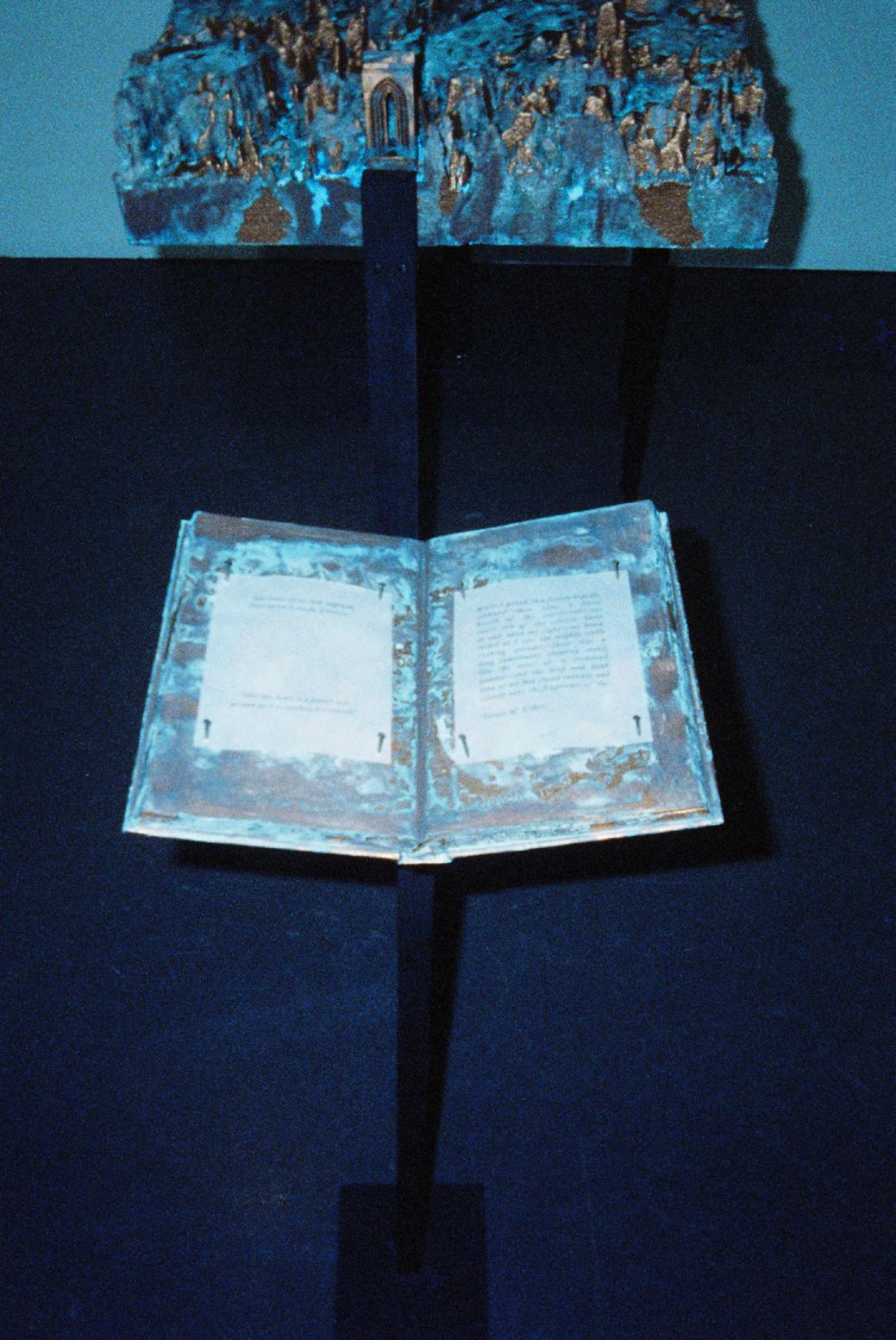

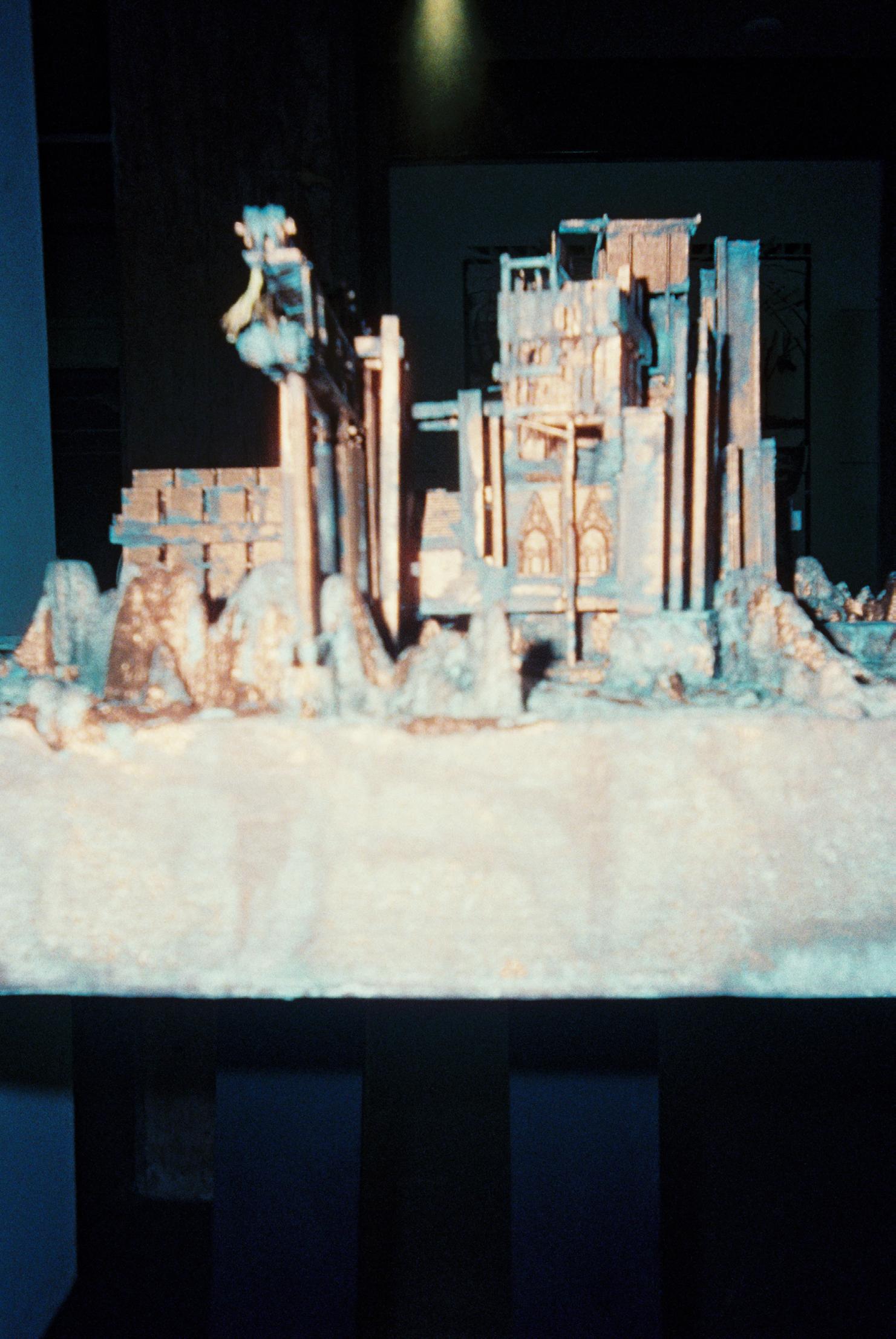

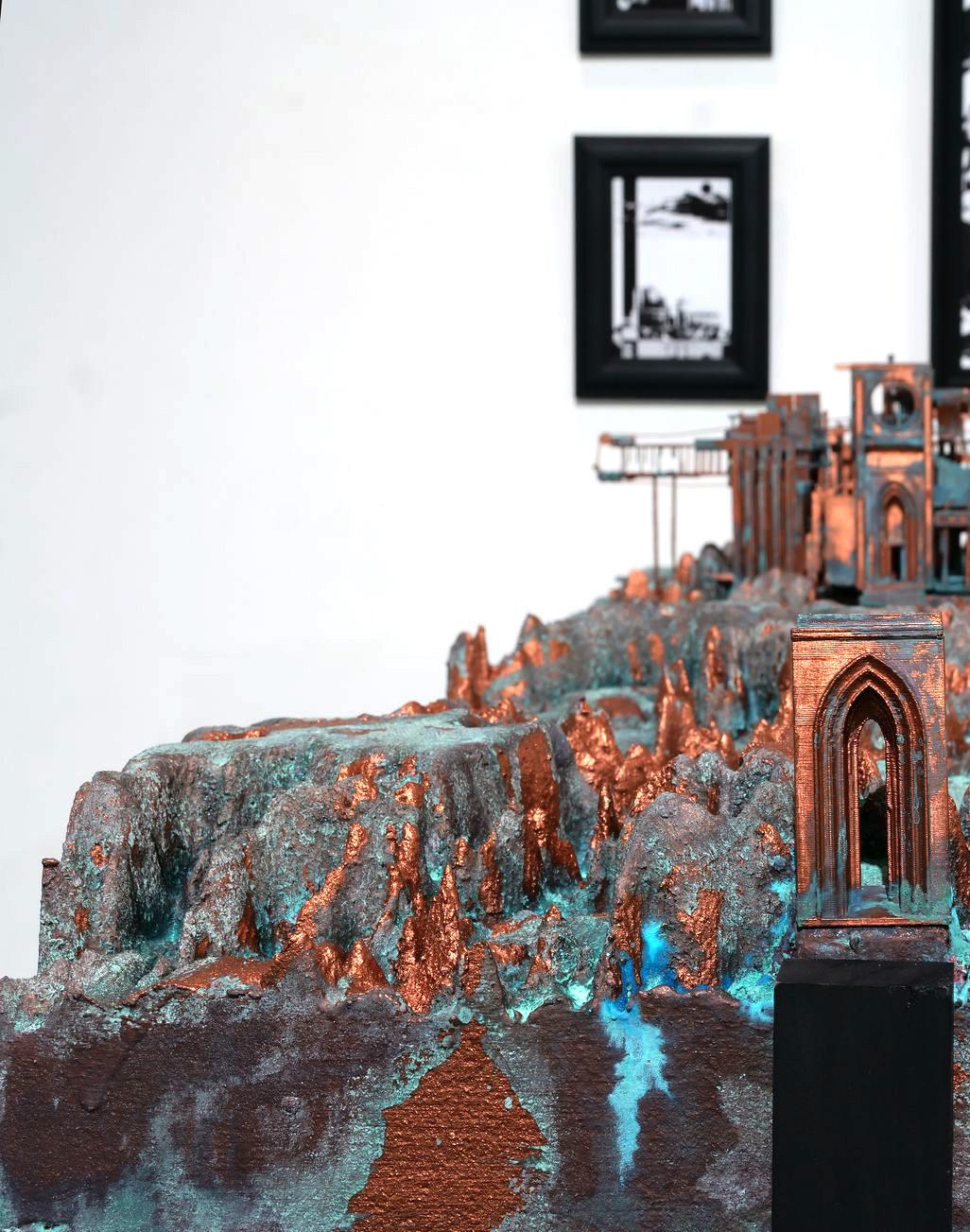

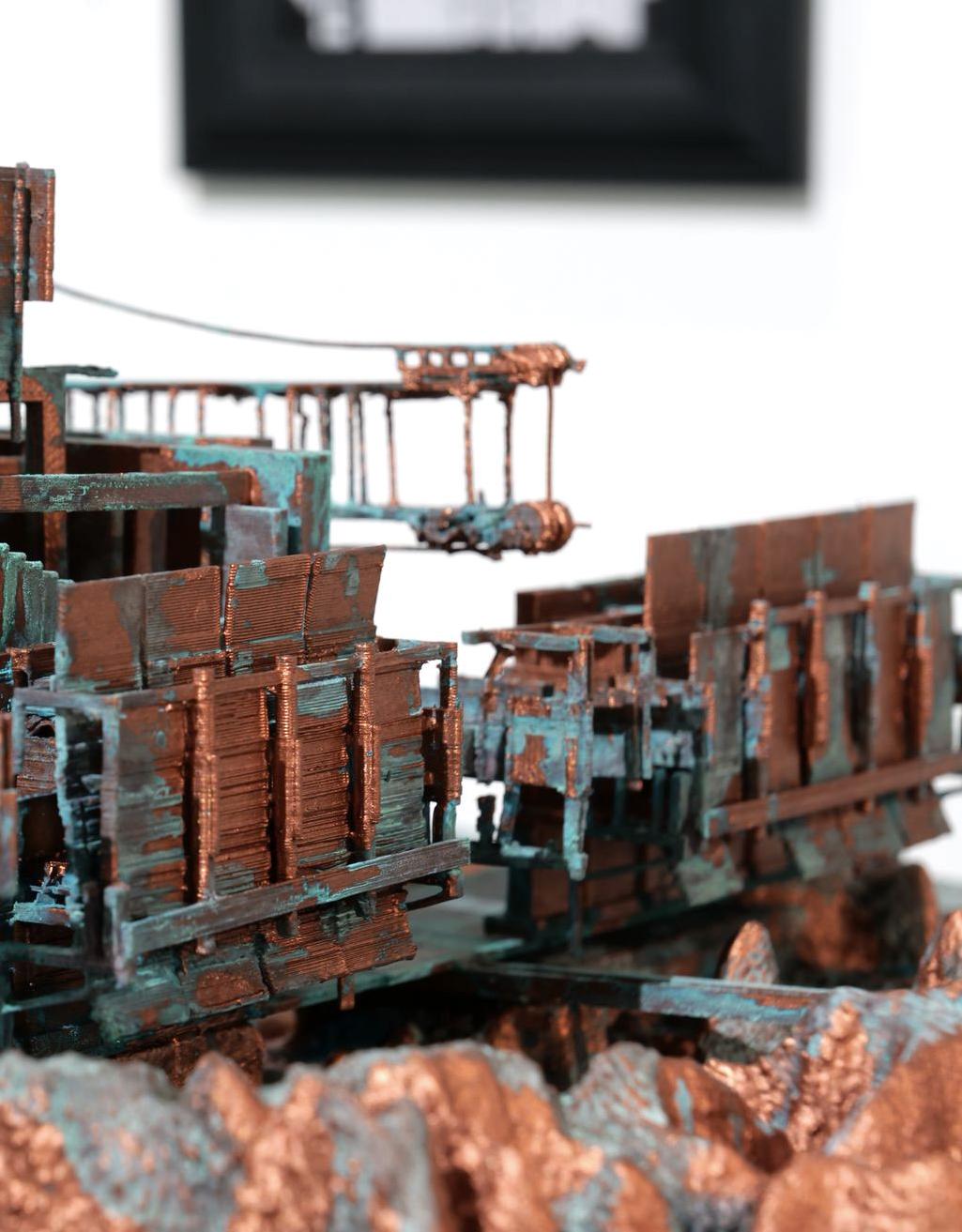

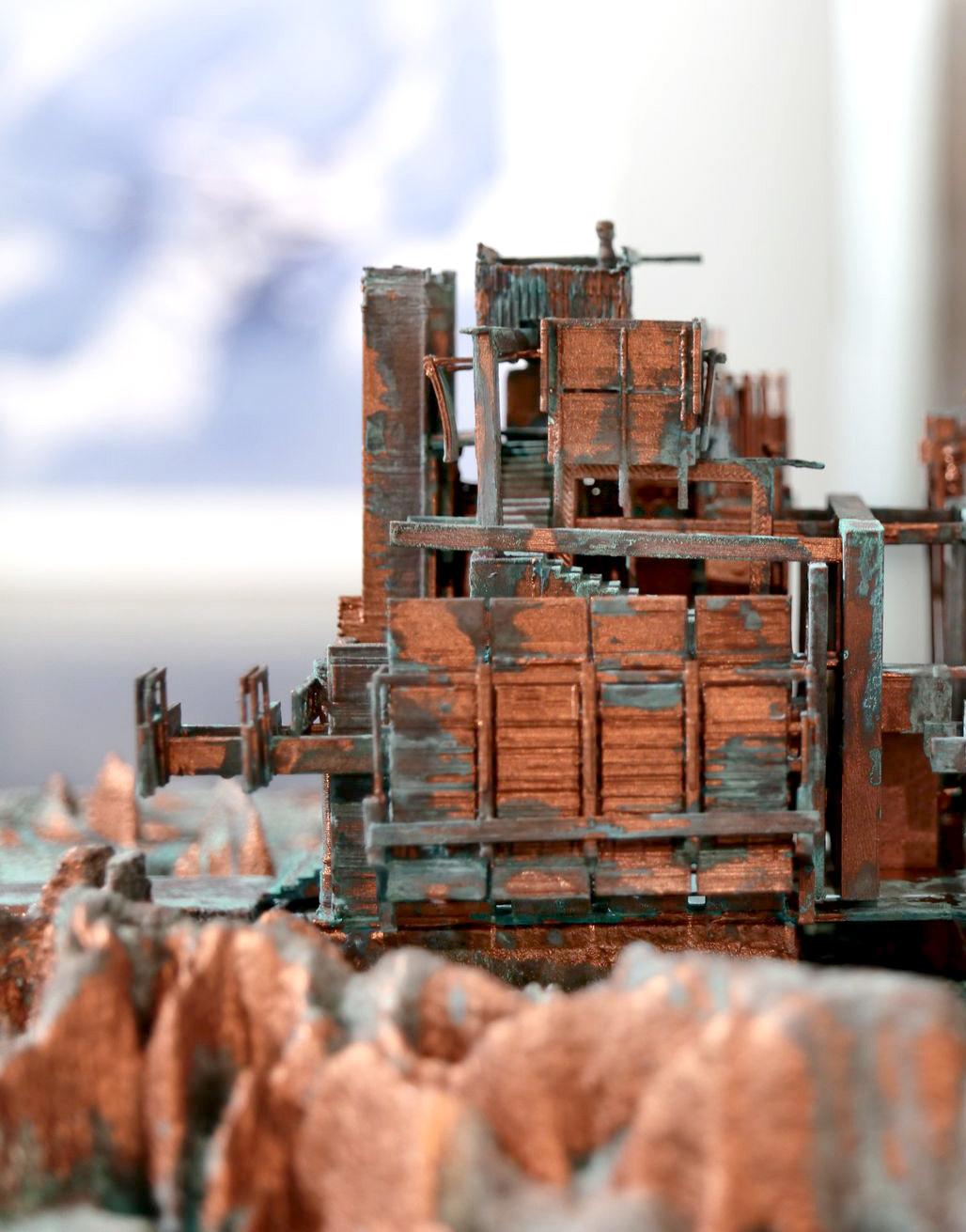

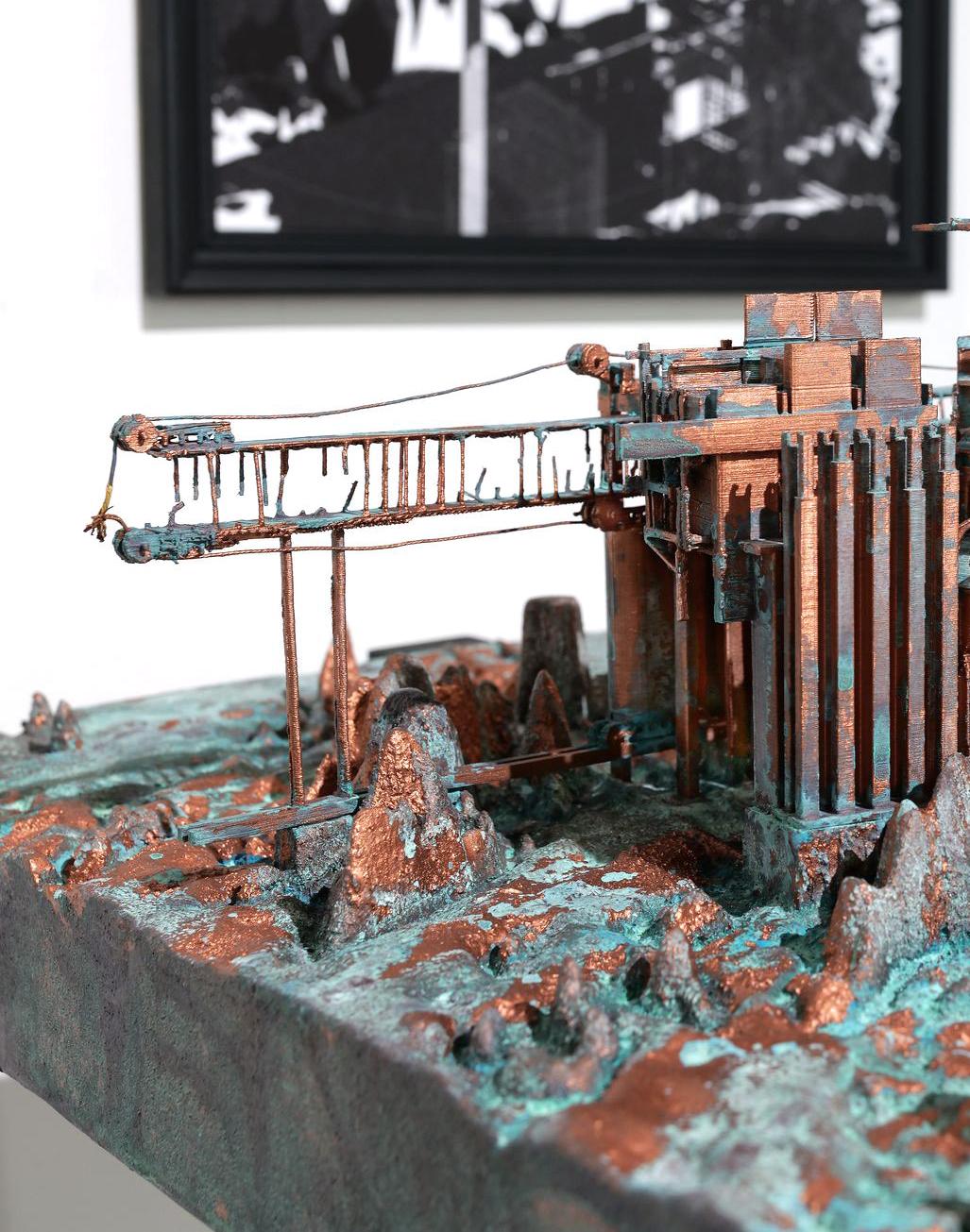

9.1 Model Discussion

10.0 CONCLUSION AND CRITICAL REFLECTION

10.1 Critical Reflection

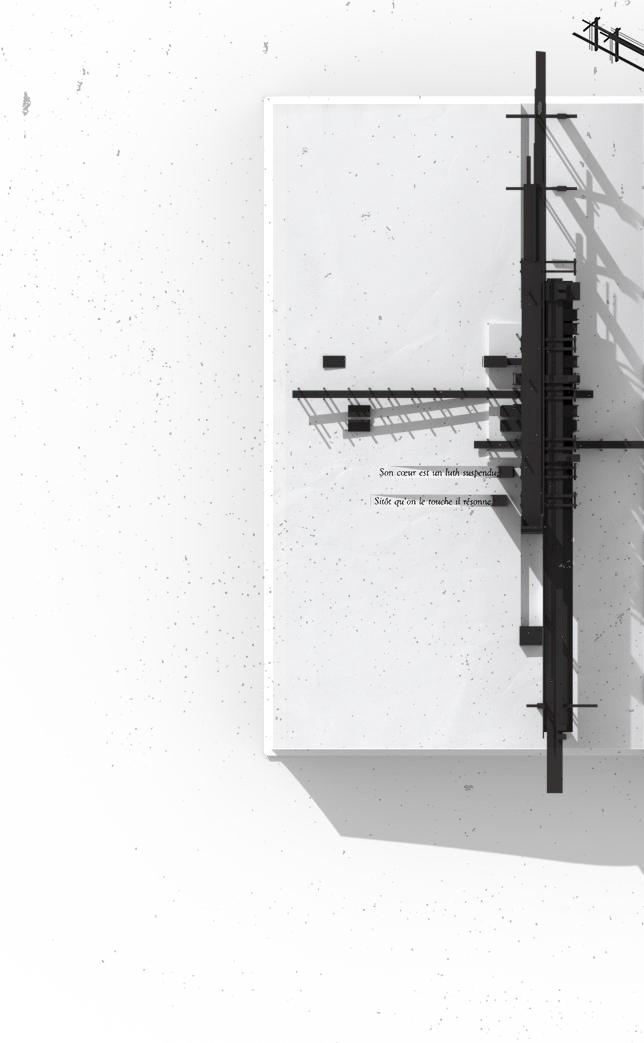

Son cœur est un luth suspendu; Sitôt qu’on le touche, il résonne.

His / Her heart is a suspended lute; as soon as you touch it, it resonates.

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Fall of the House of Usher

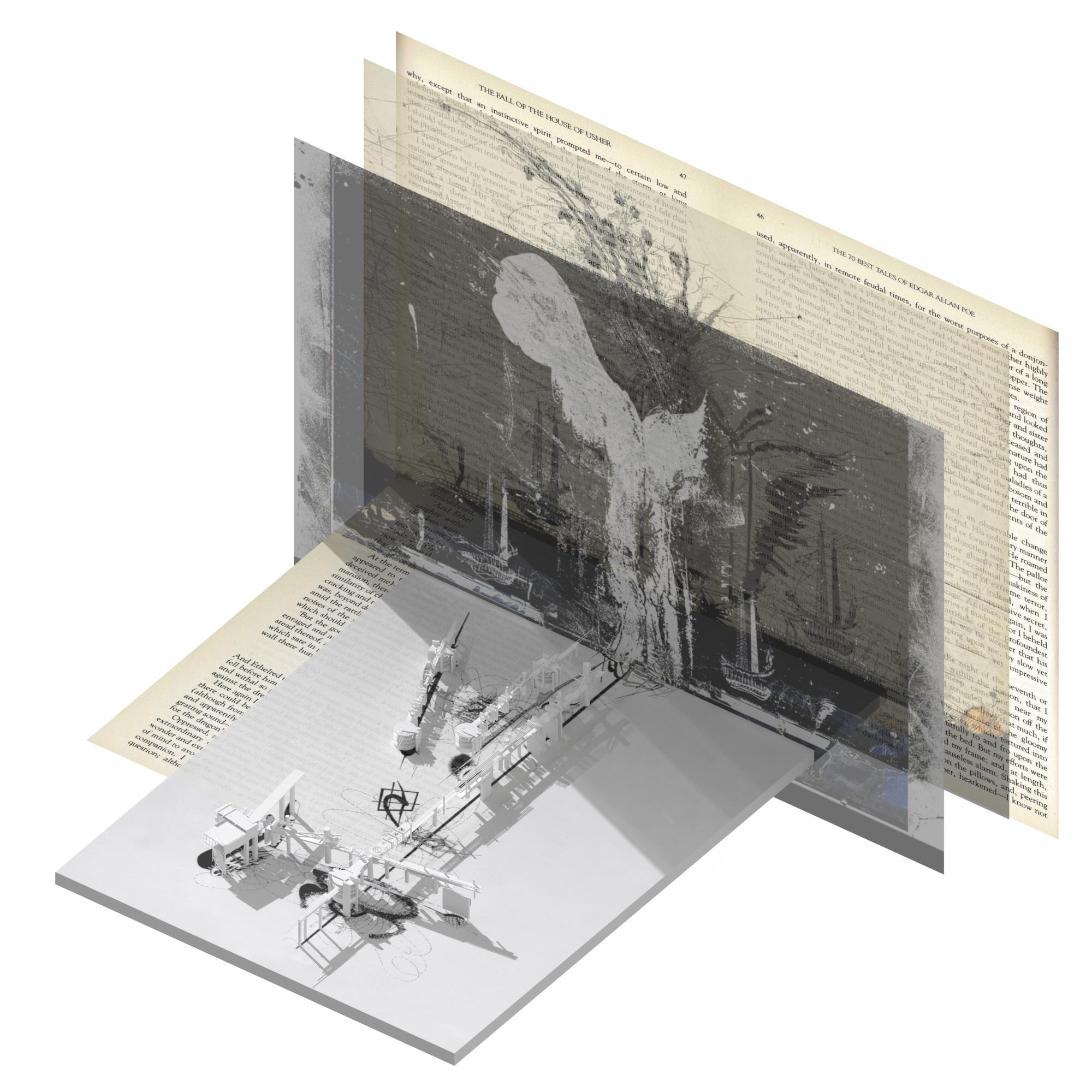

This thesis is positioned within a research stream that explores the potential of ‘allegory’ as a framework to design meaningful architectural outcomes. Its foundation is other disciplines that implement allegory, such as literature, that can convey socio-political, philosophical, among any number of other ideas that architecture traditionally cannot or does not. This thesis interrogates and applies relevant literary allegory theories (Haralambidou 225) while using a work of literary fiction, Edgar Allen Poe’s The Fall of The House of Usher (The Fall), as a provocateur for designing architectural outcomes.

The Fall has been selected as a literary provocateur. Poe’s short story tells the allegorical story of a house and its alienated dying occupants, and their ultimately fatal and final efforts to reestablish connection with the outside world. The reader assumes the position of an unnamed narrator, the outsider, who witnesses the events that transpire, the decay of the allegorical house its and inhabitants.

Within the house is a library whose books are also allegories for the occupants. The book’s obscure and occult themes set them apart from what is considered ‘normal’, and the principal occupant Roderick Usher’s obsession with them reinforces his increasing alienation from society. The books, the occupants, and the house are one, and culminate in a story that describes the ramifications upon the individual should they become alienated beyond a certain point, ending in a final scene where all but the narrator falls into the surrounding tarn.

Although Poe’s story is shrouded in the melancholic tone of gothic horror fiction, this thesis sets out to apply Poe’s framework more positively. Rather than focus on the negative implications alienation can have, this thesis uses the story as a seed for what is hoped to be a more fruitful outcome than that of the occupants in the short story; one that can instead describe and facilitate the positive implications of a connection to the wider world and society.

We live in a world that has access to a multiplicity of devices and means of communication with the outside world. Despite being more connected than ever, one can still find oneself alienated from society, whether it be through perceived difference, pandemic, ostracisation, or any number of other reasons. The primary place that can facilitate this alienation is the house and home. As Jonathan Hill explains in Immaterial Architecture (2006):

Home is the one place that is considered to be truly personal. Home always belongs to someone. It is supposedly the most secure and stable of environments, a vessel for the identity of its occupant(s), a container for, and mirror of, the self.

However, the concept of home is also a response to the excluded, unknown and unpredictable. Home must appear solid and stable because social norms and personal identity are shifting and slippery. It is a metaphor for a threatened society and a threatened individual. The safety of the home is also the sign of the opposite, a certain nervousness, a fear of the tangible or intangible dangers outside and inside. The purpose of the home is to keep the inside inside and the outside outside. (8)

The House which began traditionally as a public-orientated space has over time become privatised and creates a definite and defined boundary between the inside and outside. It is for this reason that the house easily becomes a sanctum for the alienation of the individual in which they can recluse.

This thesis uses Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Fall of the House of Usher as a literary provocateur for the design of an allegorical architectural project. In his story Poe uses architecture, the Usher house, as an allegorical device to convey the theme of alienation from society, and the dangerous ramifications it brings for an individual. This thesis investigation seeks to re-present this theme from Poe’s short story as a work of architecture, addressing the house’s role in the alienation of the individual.

This design-led research investigation proposes to use Edgar Allen Poe’s allegorical short story The Fall of the House of Usher as a literary provocateur for an architectural project, interrogating how Poe’s primary literary devices of allegory, alienation, artifact, dialectic dialogues, and temporality, can be used beyond literature and applied spatially.

To achieve this goal, this thesis investigation explores literary and architectural theory relating to artifacts, dialectics, and temporality; applying it to varying degrees and conceptions of the ‘house’ in such a way that challenges normative common practice in the designing of a house.

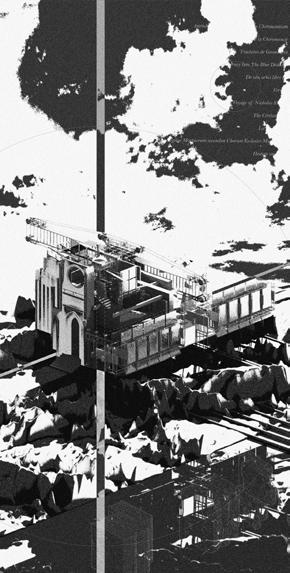

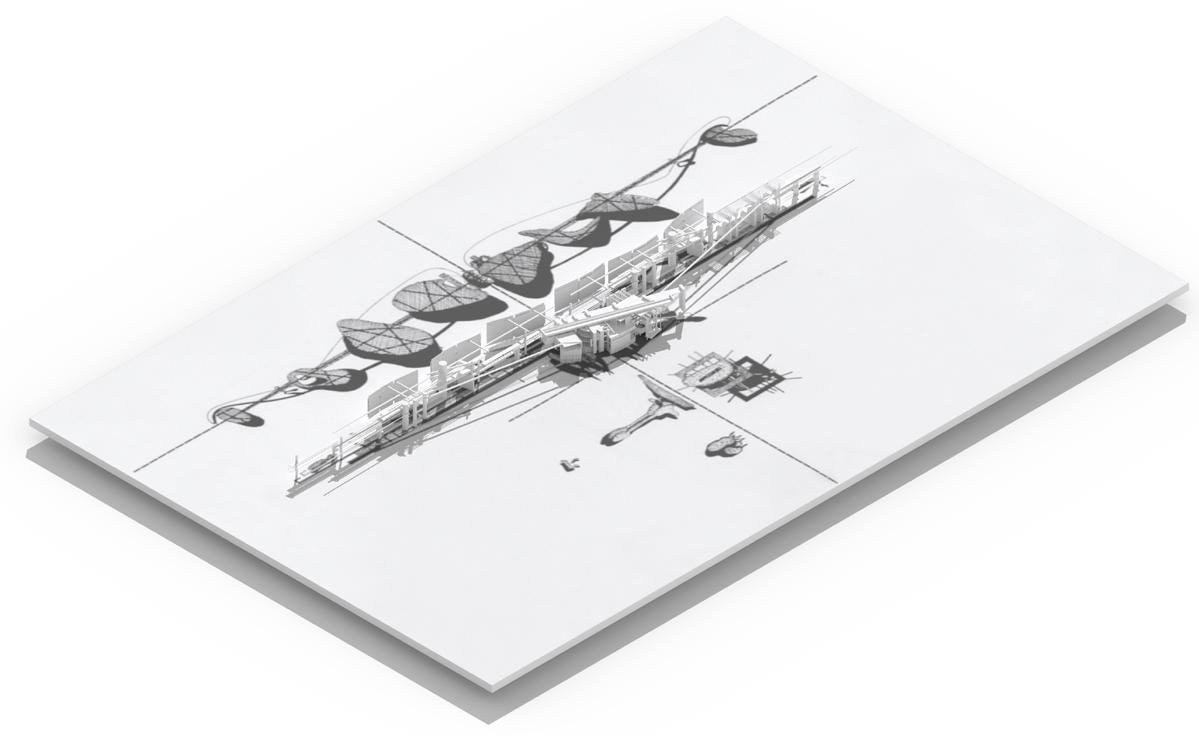

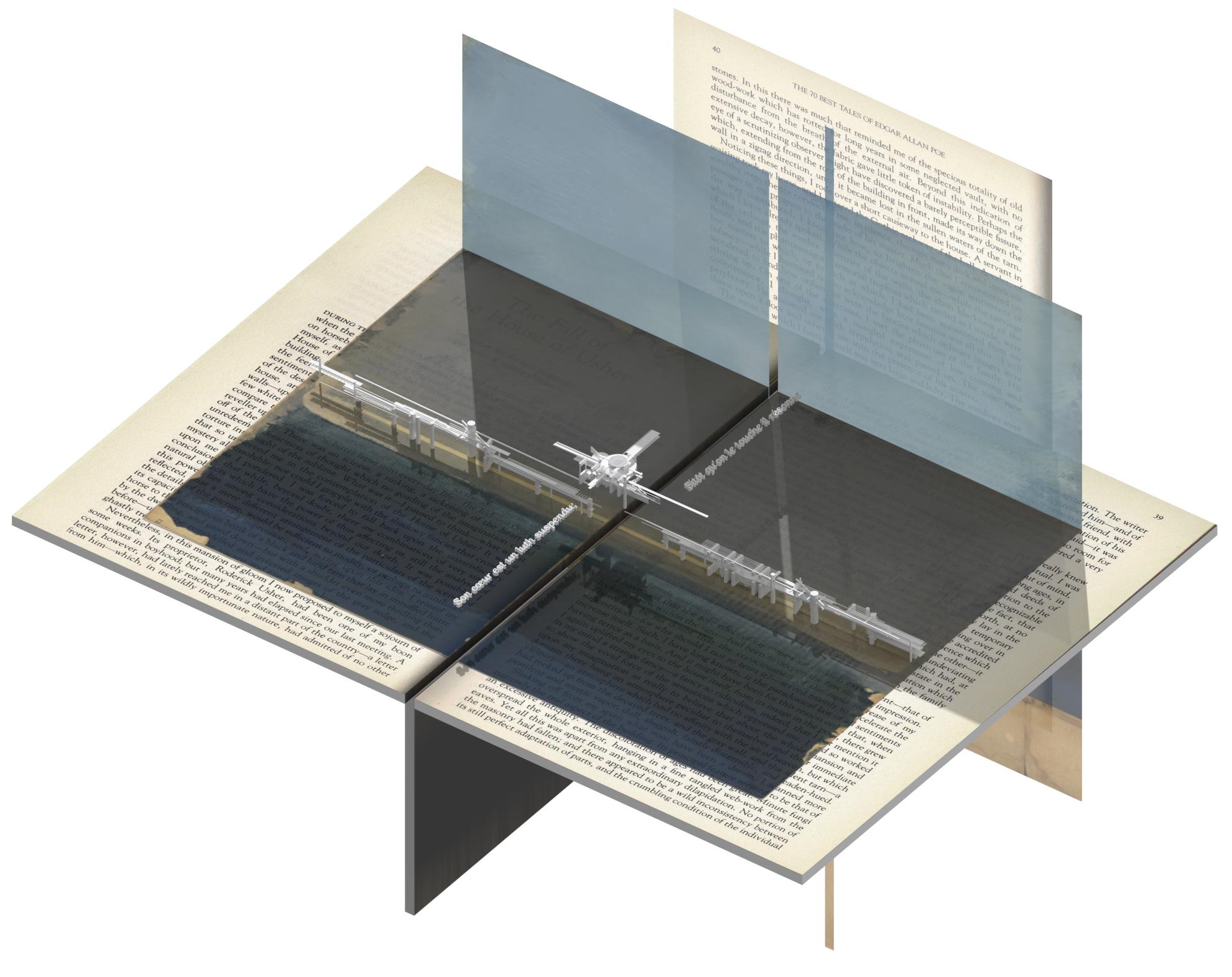

The sites for this investigation are purely speculative and use variations of the book as site and context, and then finally an extrapolation of Poe’s tarn from The Fall as its final context.

Titled The Fall of the House, the investigation challenges the preconception of what a house could and should be, proposing a new way of engaging the design of the house that commentates and brings the key issue of alienation to light. Although existing in a speculative realm it is hoped that the investigation can prompt a discussion that can also be applied to the wider realm of nonspeculative residential architecture in the hopes to address not only alienation in the built environment but also a new approach to the ‘house’.

Home is the one place that is considered to be truly personal. Home always belongs to someone.

Jonathan Hill, Immaterial Architecture

1.3 Alienation.

This design-led research investigation asks:

How can an allegorical architectural project be used as a critical method to enhance understanding of alienation?

The principal Research Aim of this design-led research investigation is:

RA to investigate how an allegorical architectural project can be used as a critical method to enhance understanding of the individual’s alienation from society, and the role the house plays in that relationship.

The three principal Research Objectives of this investigation are:

RO1 Artifact to explore how theories relating to Artifacts can be used to create a context for an allegorical understanding of alienation.

RO2

RO3

Dialectic Dialogue to explore how Dialectics can be applied to Artifacts in creating relationships and dialogues between them that convey the allegory of alienation.

Temporality to explore how architectural theories relating to temporality can provide an allegorical architectural context representing the decay of artifacts over time and their relationships with one another in expressing the allegory of alienation.

“A short story must have a single mood and every sentence must build towards it.

”

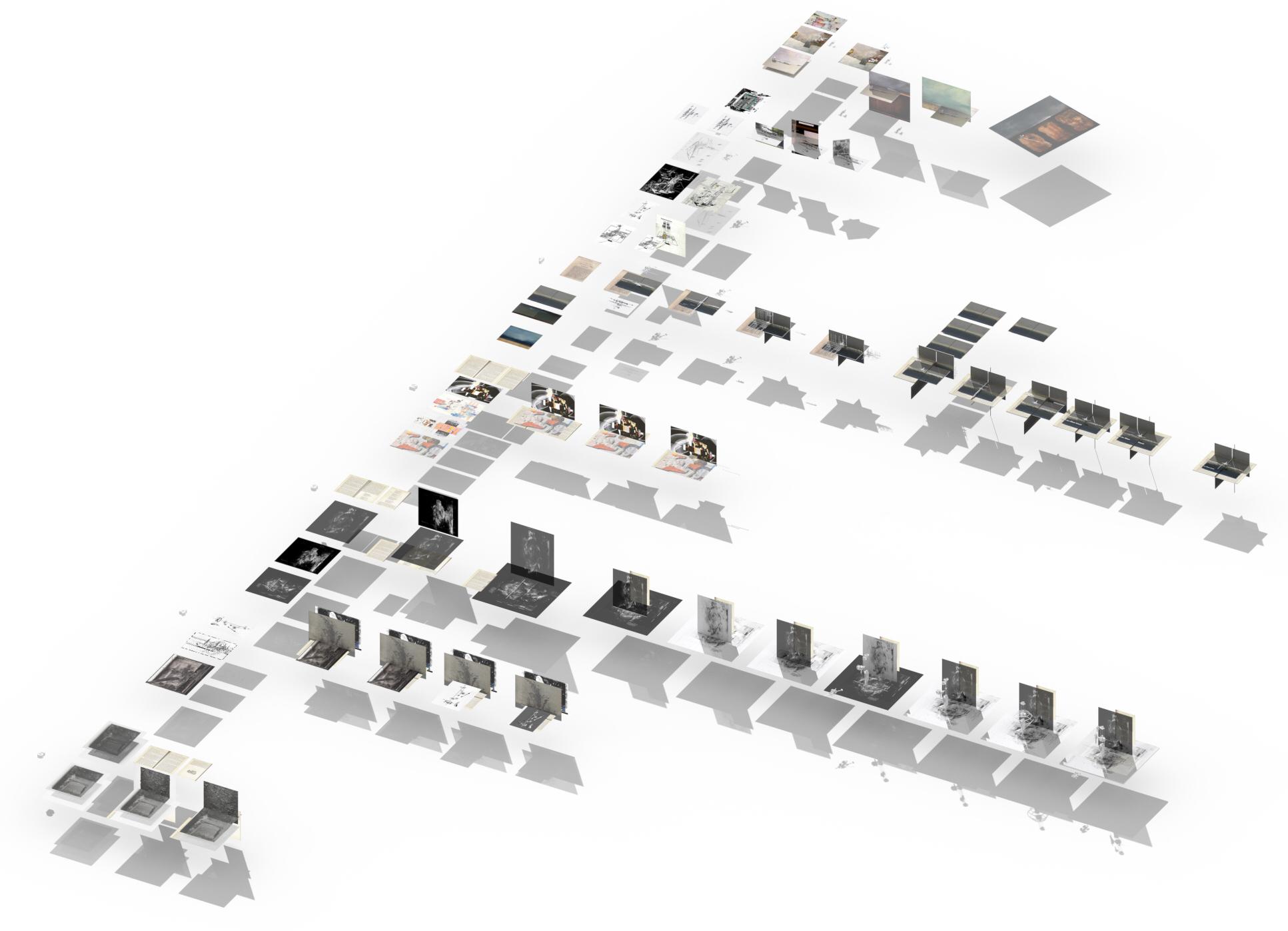

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Philosophy of Composition

This research investigation follows the iterative processes depicted in the methodology diagram shown in Figure … . Each Research Objective and its corresponding theorists and case studies are used to iteratively interrogate each stage of this investigation. The methodology for this research investigation represents “research by design”, as critically discussed in Peter Downton’s book Design Research (2003). This thesis engages an iterative design-led research approach, using a sequential workflow of digital techniques that progressively build upon each outcome. Each successive stage of the design research is used to conduct experimental research that reflects the previous stage and anticipates the stage to come. Each stage critically reflects on strengths and weaknesses, and each interrogates opportunities for the next design stage concerning this critical reflection.

This research seeks to investigate three-dimensional speculative architecture that reflects Poe’s literary interpretation and commentary on alienation and isolation. The final design experiment is not intended to solve the impossible and endless issue of alienation, rather it is intended to serve as an evocator to facilitate self-reflection and open a dialogue on alternate methods for the design of a house. The intent is that through the fusion of literary fiction, architecture, and reality, the reader may come to question and understand their relationship with the house and alienation, and ultimately enhance that relationship productively and positively.

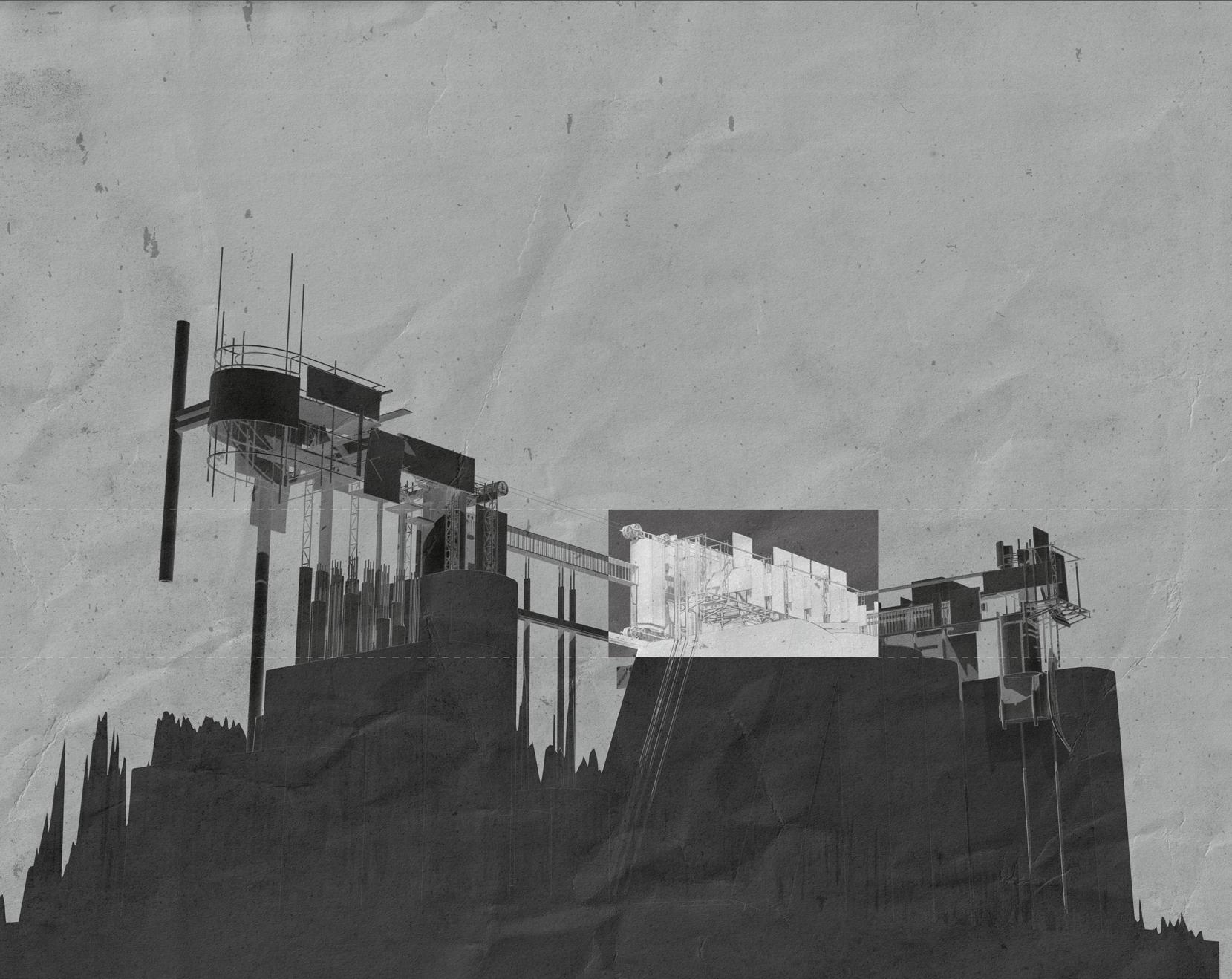

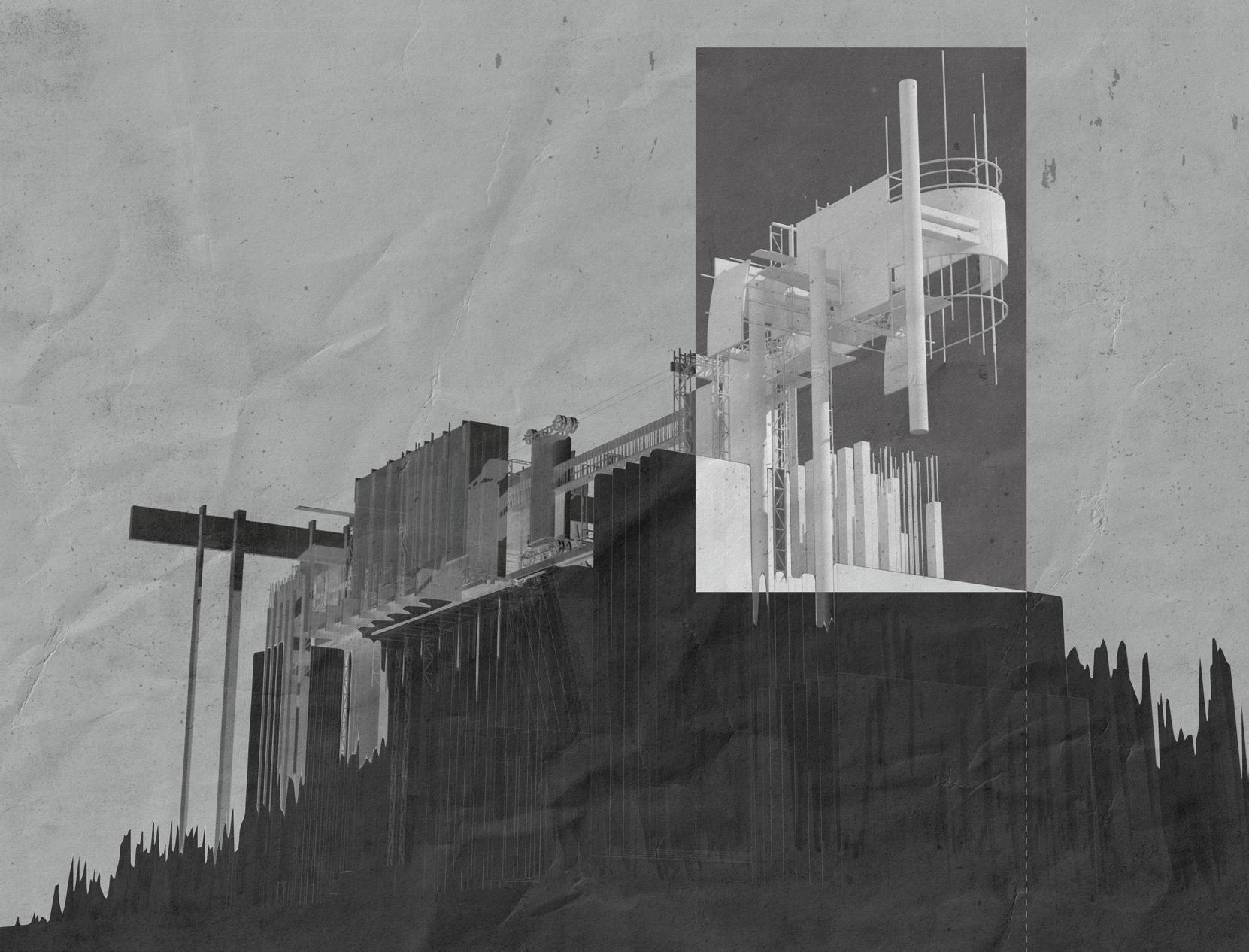

I know not how it was — but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment, with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. I looked upon the scene before me — upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain — upon the bleak walls — upon the vacant eye-like windows — upon a few rank sedges — and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees — with an utter depression of soul which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveller upon opium — the bitter lapse into every-day life — the hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart — an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime. What was it — I paused to think — what was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher?

Using speculative allegorical architecture as a critical method comes with certain limitations. To fully explore and express Poe’s allegory and framework within architecture, aspects of a traditional architectural project are outside this investigation’s scope. This includes elements such as costing, architectural structure, technologies etc. What is important in the outcomes is that they reflect the Research Objectives and Research Aim and explore them and their capacity to their fullest extent. The nature of the aim, and goal to take this to the public realm for exhibition, means that it should still be accessible to the public and should not stray so far from the world of the ‘real’. For this reason, the outcomes still need to have the potential to be realised in such a manner that people could place themselves within the design to be able to open a dialogue on the key issue of alienation, and in the case of the developed design could be imagined as a ‘house’. Future development on the project with more time could lead to the implementation of a physical site, that itself embodies alienation, but for the purposes of this thesis remains purely speculative.

The allegorical architectural project, although at times visually and physically inhabited, is often disconnected from the material construction of a building. The imaginative, sometimes poetic bringing together of ideas positions it closer to visual literature and, because of its high dependency on narrative, it can be a bridge between a work of art, painting or sculpture, and a literary text, poem or novel.

-Penelope Haralambidou, “The Fall: The Allegorical Architectural Project as a Critical Method”

1.0 Introduction

Chapter One outlines the Problem Statement, Research Proposition, and Research Question proposed by the thesis. The chapter also discusses the Research Aim, three Research Objectives, Methodology, Scope of Research, and Thesis Structure.

Chapter Two provides a brief discussion of Poe’s short story The Fall of the House of Usher which is being used as an allegorical provocateur. The chapter examines the allegory of alienation within the story, the occupants, the books, the library, and the house.

3.0 Literature & Project Review

Chapter Three establishes the theoretical framework for the research investigation. It analyses theories from key authors and case studies relating to the Research Aim and three principal Research Objectives, that will be applied iteratively in the design process of the thesis.

4.0

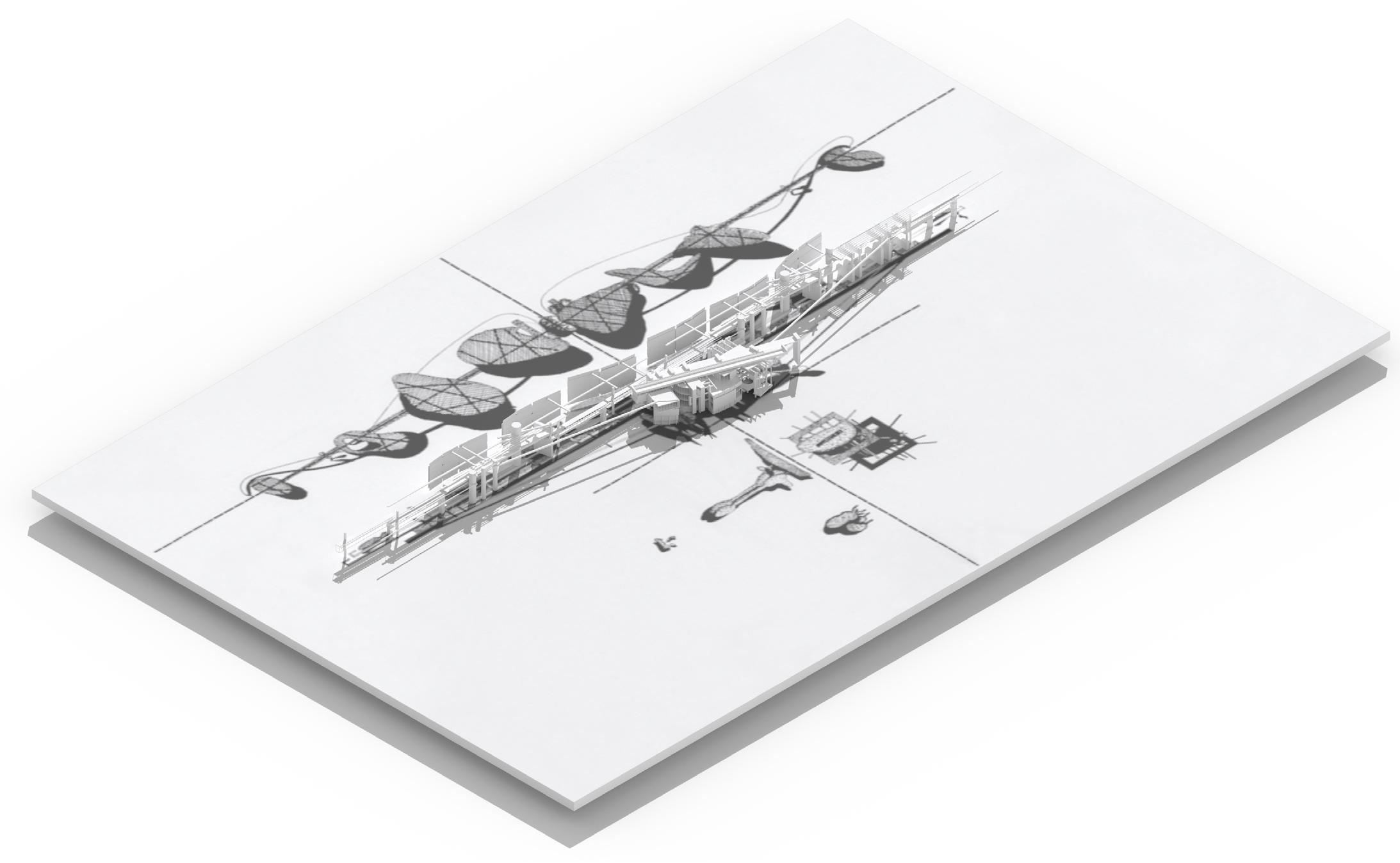

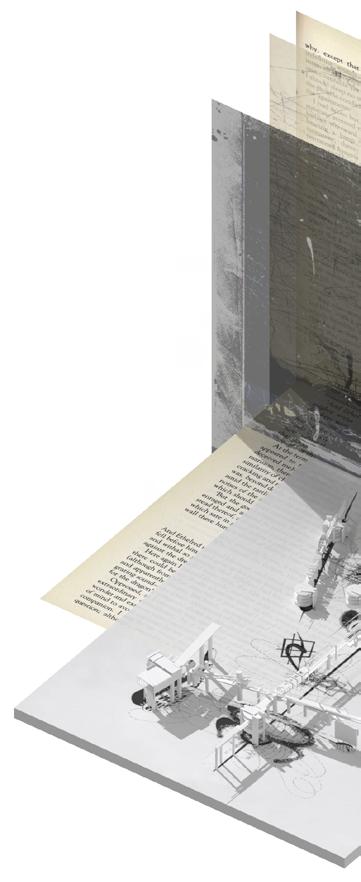

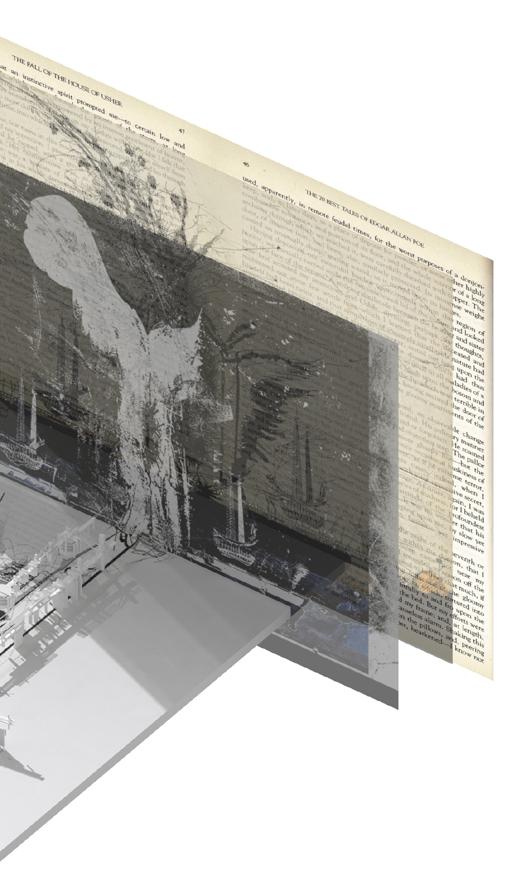

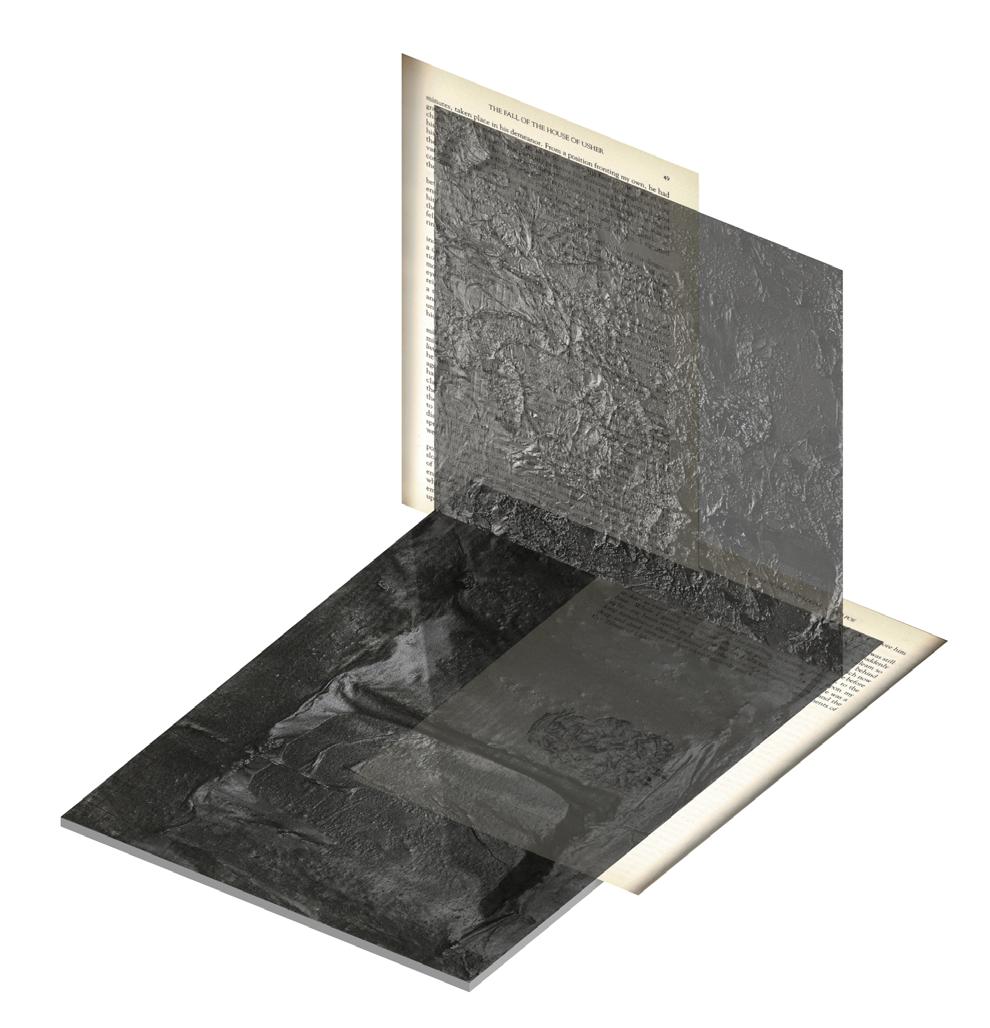

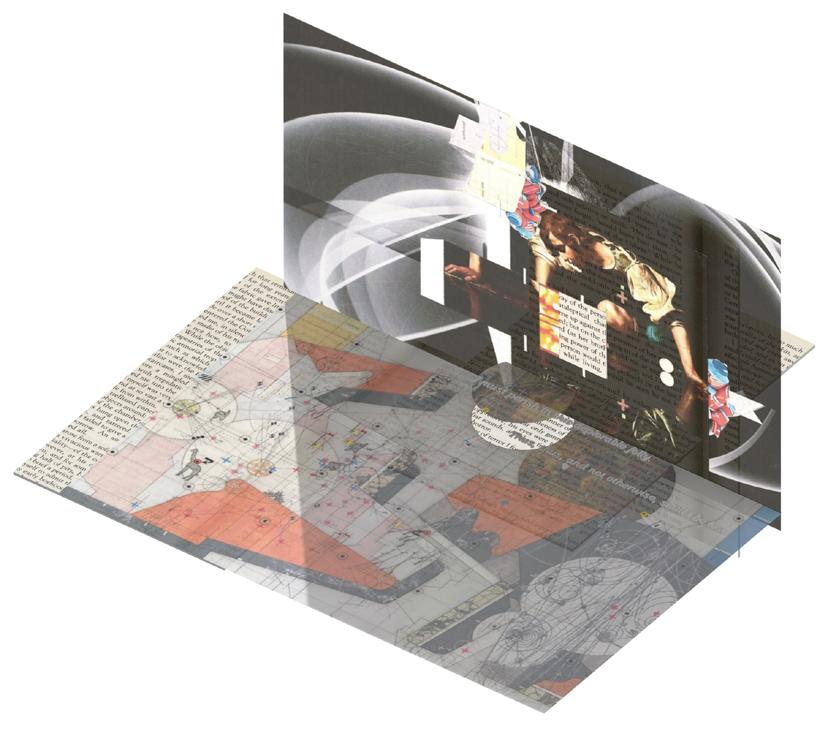

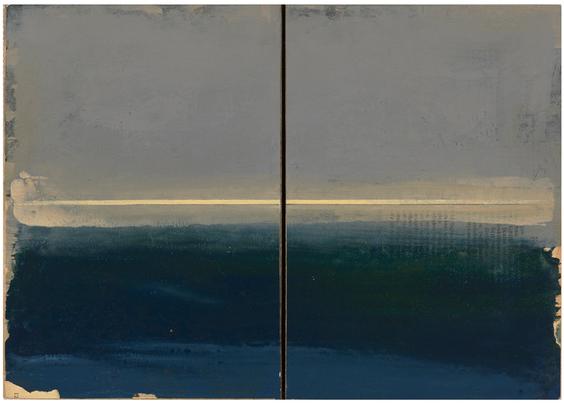

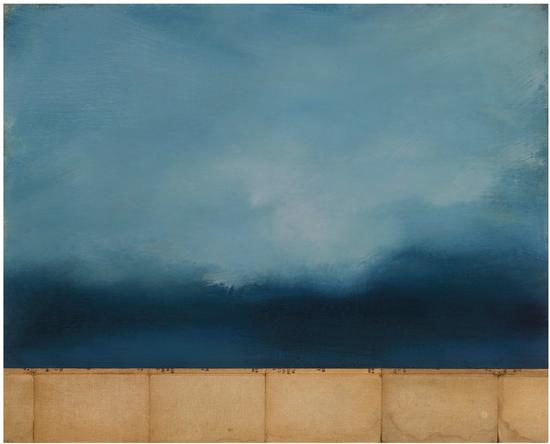

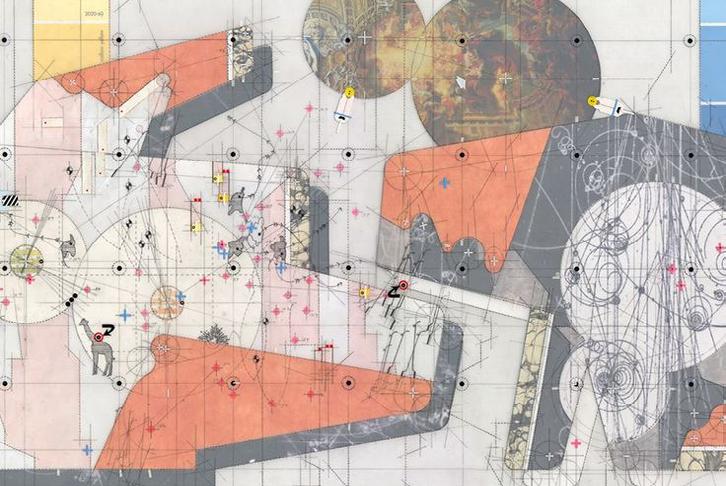

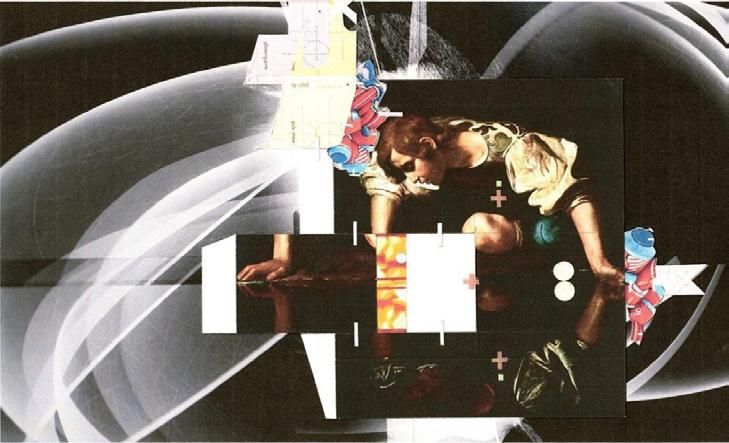

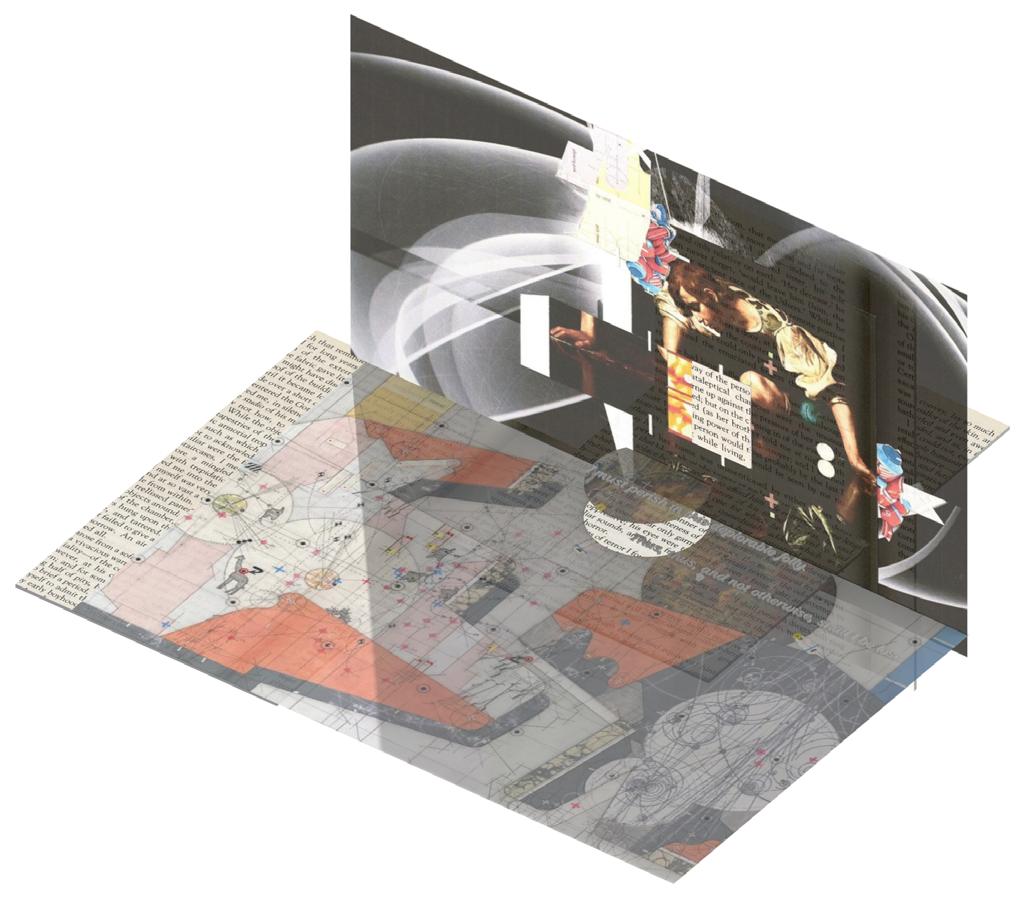

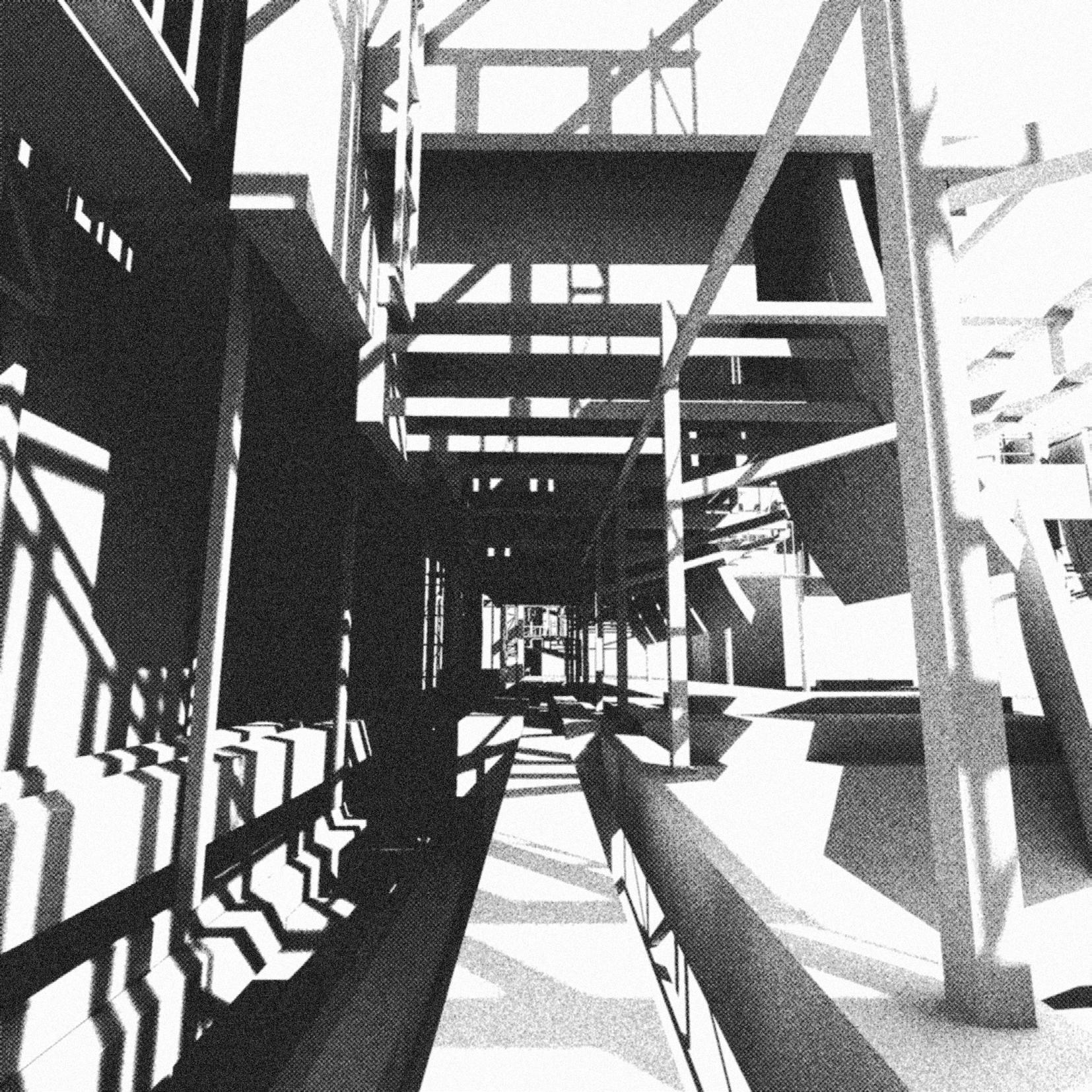

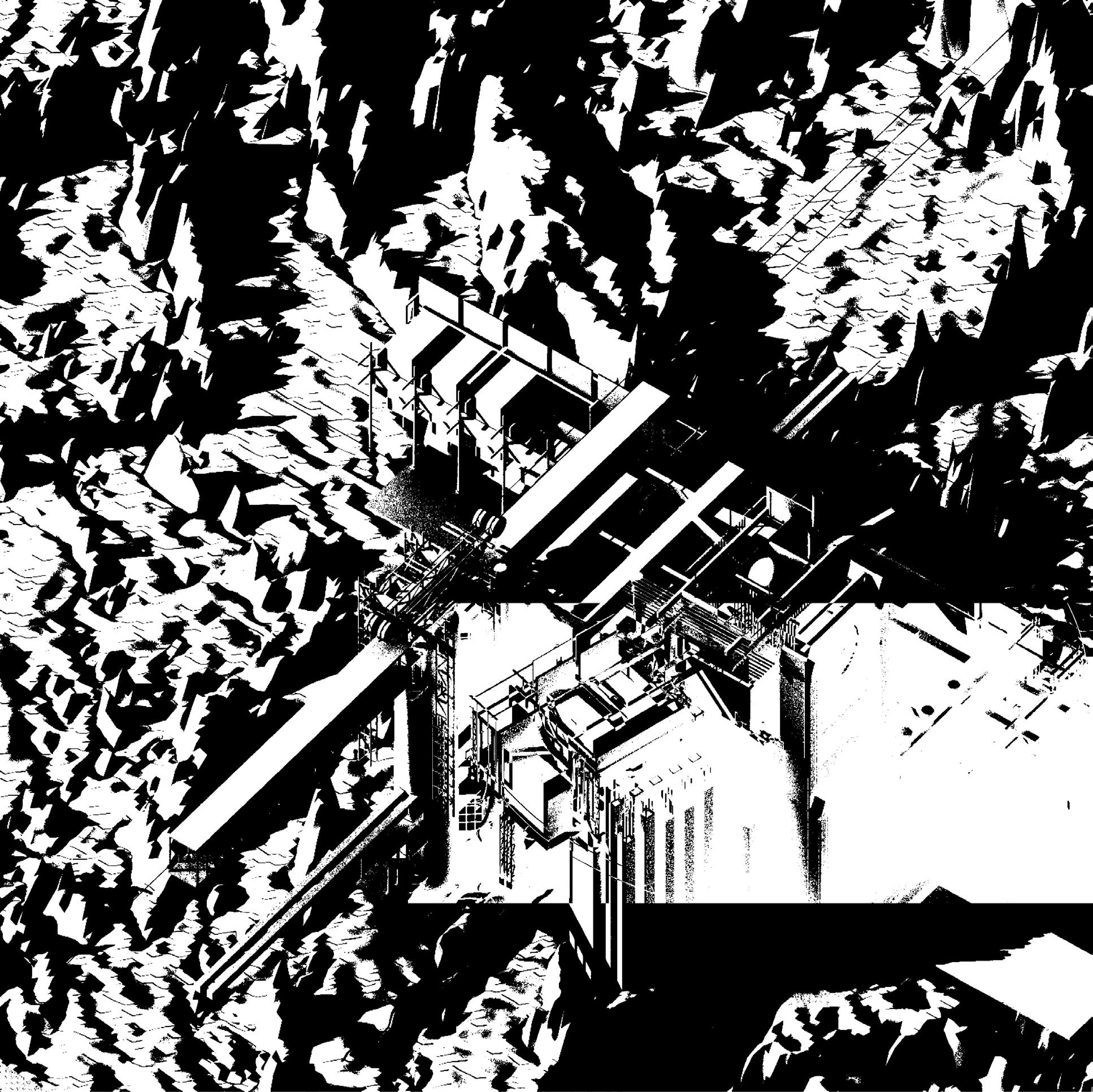

Phase One investigates how other allegorical media, art pieces, can be used in conjunction with Poe’s short story to generate a three-dimensional architecture that reflects the allegorical books and art simultaneously. The design experiments are produced using primarily digital modelling upon layered artworks, reflecting themes drawn from Poe’s framework, addressing RO1 Artifacts and RO2 Dialectic Dialogues.

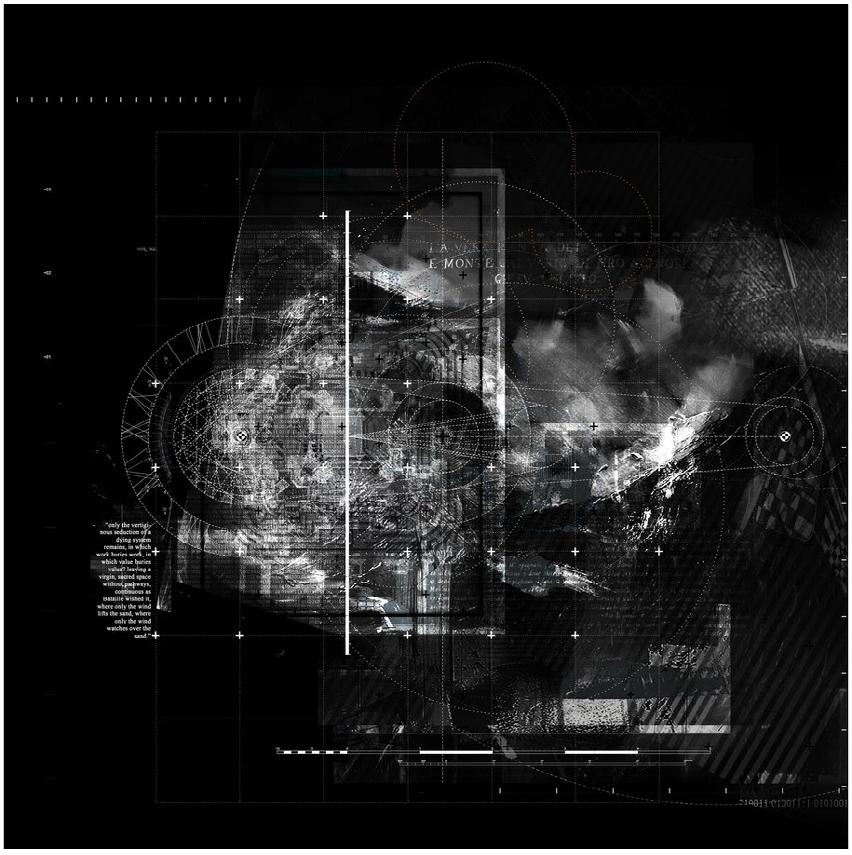

Phase Two critically reflects on the prior phase, shifting focus to the creation of the library that would contain the allegorical books. Artworks are replaced by architectural case studies that are adapted to become libraries. RO2 Dialectic Dialogues is implemented more thoroughly, testing dualities between book and container, interior and exterior, and opposing axes. RO3 Temporality also begins to be implemented through implied movement and shifts within the designs.

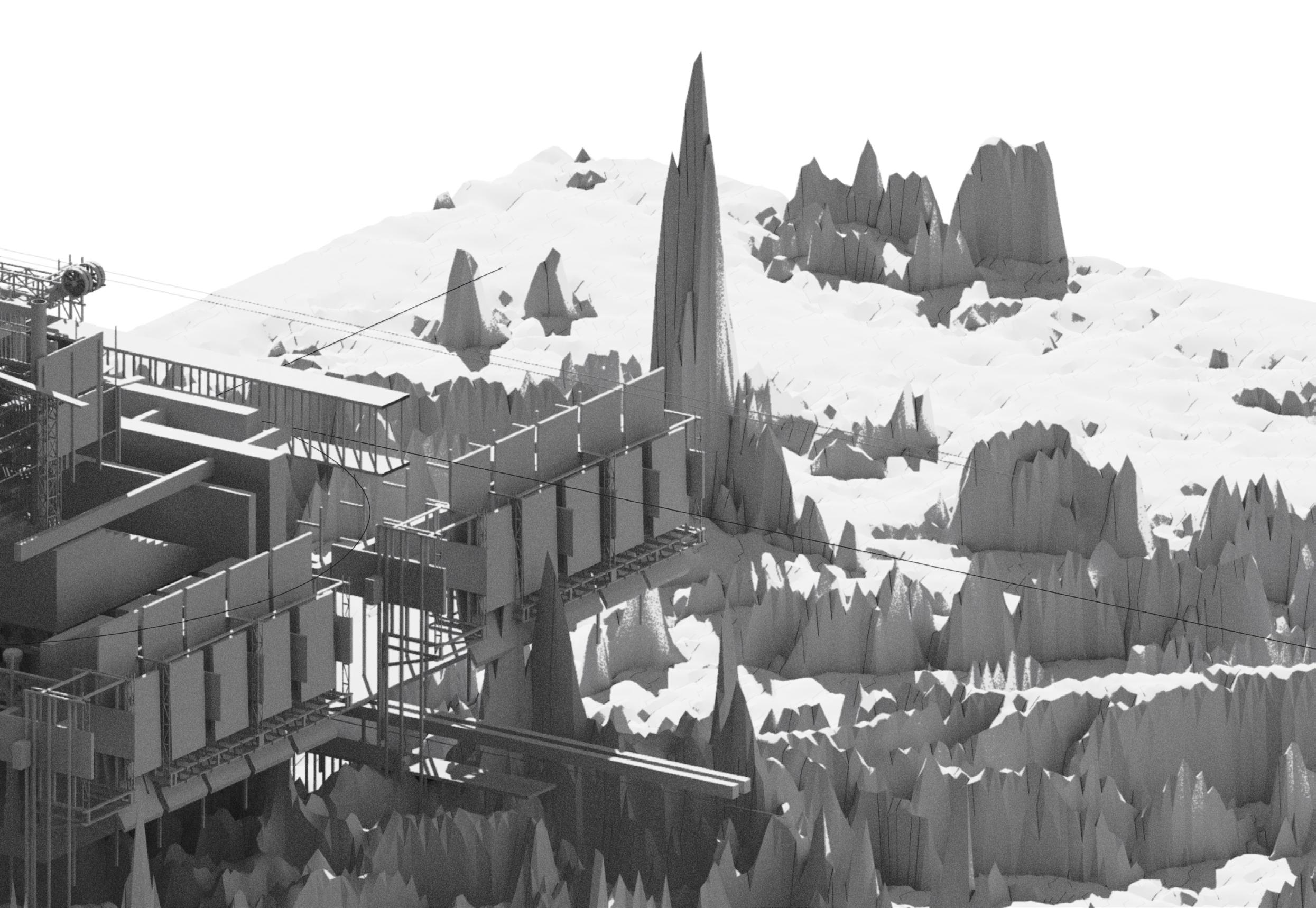

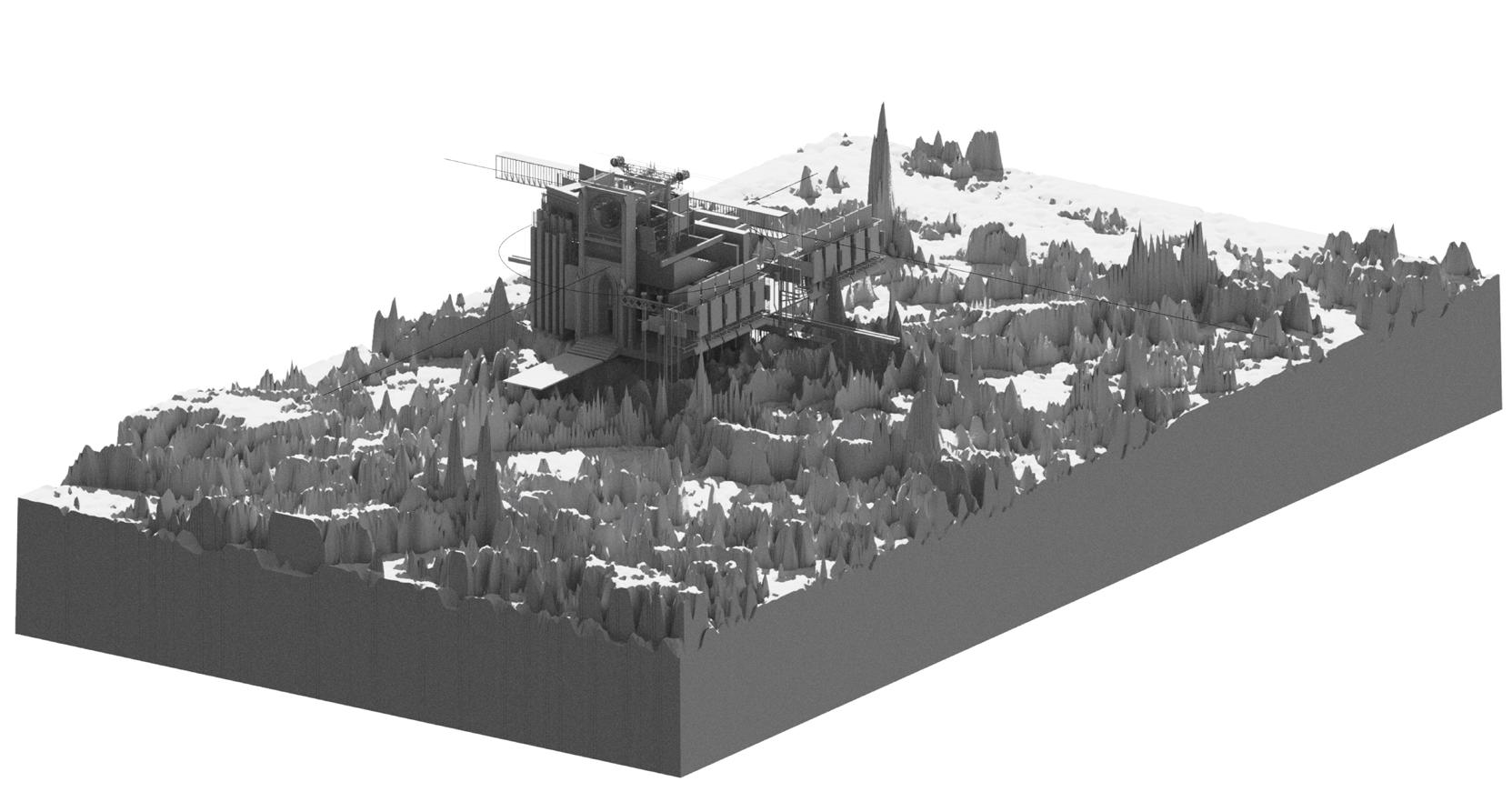

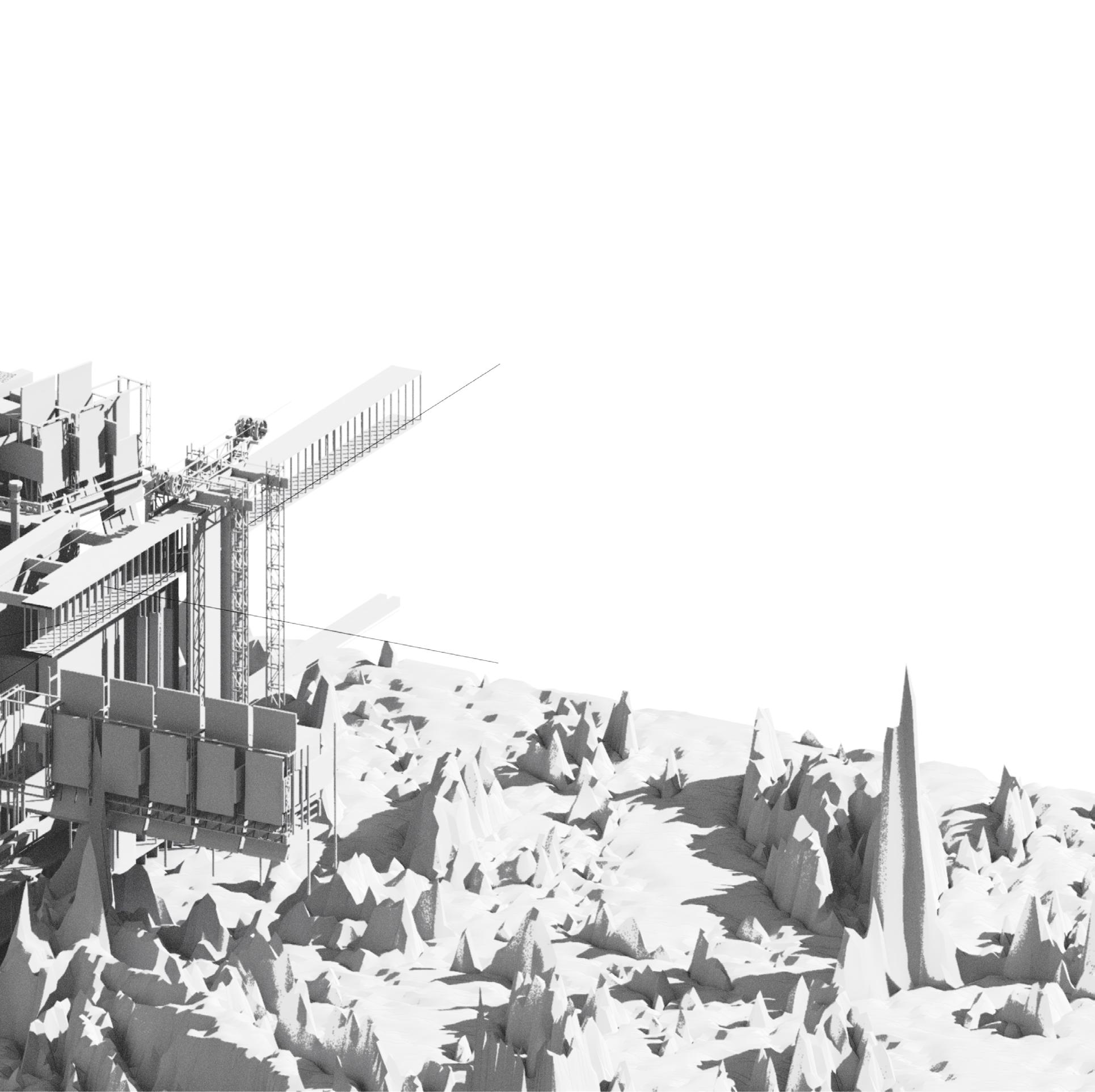

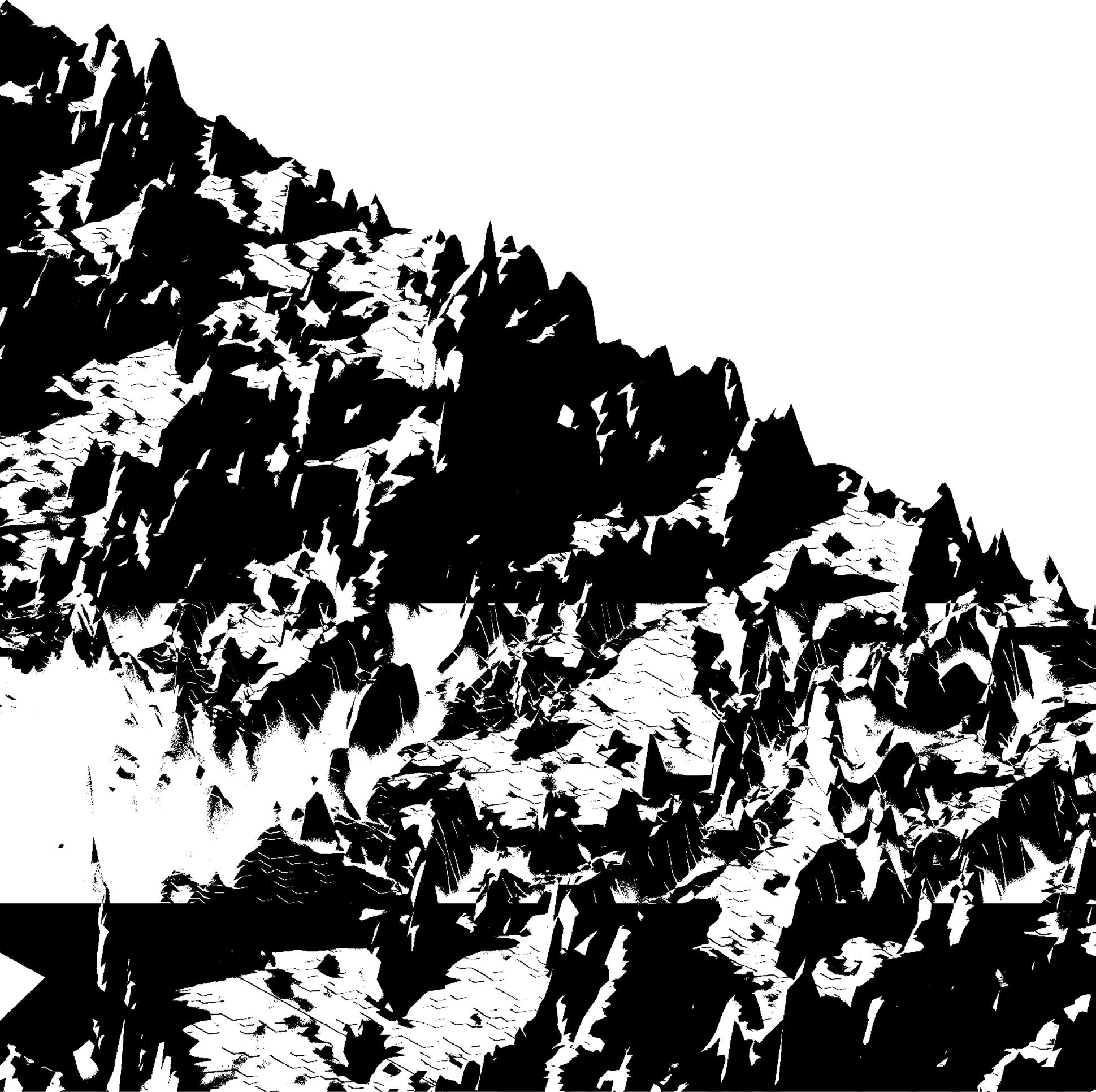

Phase One develops upon the strongest experiment from Conceptual Design Phase Two. This chapter explores the books as a context and site for the architectural intervention of a library that both contains and embodies the allegorical books within. The books become both the context and the architecture that it sits upon. All three Research Objectives are applied within a new context and explored in more depth.

Phase Two of the Preliminary Design Chapter emphasises the implementation of the Research Objectives through the architecture as opposed to relying on the landscape, as was the case in Phase One. The architecture is further iterated upon with new additions that continue to explore and address the three ROs in more depth to address the Research Aim.

8.0

Chapter Eight applies the learnings of the previous four chapters to create one final architectural intervention, the house, that encompasses all Research Objectives more effectively to address the Research Aim. The chapter ends by critically reflecting on how well the Developed Design address the RA and ROs of the thesis investigation.

9.0 Exhibition

This chapter displays images from the exhibition of the outcome from the Developed Design chapter in the public realm, at the NZ Academy of Fine Arts in Wellington.

Chapter Ten is a collective critical reflection of the thesis as a whole, critically discussing the findings, processes, and challenges of the research. Through individual reflection at the end of each chapter and holistically as a whole, the chapter evaluates the importance of the issue being investigated. The critical reflection discusses the application, opportunities, and limitations for expanding the research in the future if pushed beyond the original scope.

“The difficulty of literature is not to write, but to write what you mean, not to affect your reader, but to affect him precisely as you wish.

- Robert Louis Stevenson, Virginibus Puerisque

2.0 THE FALL OF

Literature adds to reality, it does not simply describe it. It enriches the necessary competencies that daily life requires and provides; and in this respect, it irrigates the deserts that our lives have already become.

- Paul Homer, C. S. Lewis: The Shape of His Faith and Thought

As the adjacent quote from Homer describes, literature has the capacity to not only describe reality but add value to it. I would then argue that the practice of layering and applying the allegory of literature to the built environment results in a design that not only is suitable for its purpose but adds to the experience of the user. It is this premise that forms the basis of this thesis and implementation of Poe’s story, and thus it is important to include a brief discussion on the contents of the story and context for the following chapters.

Firstly, worth note is that there are a multitude of readings of Poe’s story. I would like to propose that there is no one ‘correct’ reading of The Fall, but rather a collection of themes that all add to the narrative and tone that Poe wished to convey, which is left to the reader to interpret. Among these readings is that of the alienated individual from society, which I see as one of, if not the most, prominent allegories within the story. This also has the strongest relation to the built environment, and hence it is the provocateur for this thesis.

The story tells the allegorical tale of a house and its alienated dying occupant, Roderick Usher, and his ultimately fatal and final efforts to re-establish connection with the outside world. The reader assumes the position of an unnamed narrator invited to the house to relieve Roderick of his unknown malady. Despite this effort to reconnect with the world, it is too late, and the house and Roderick continue to decay. The finale of the story sees the escape of the narrator as the house crumbles into the surrounding tarn, along with Roderick Usher. There are a range of techniques and elements that Poe employs to convey the allegory of alienation, this thesis reflects primarily on three; the house, its library, and the books within, which all reflect the occupant, Roderick.

The description of the house from the onset of the story stresses its isolation from the world and the known. The narrator’s only insight into the setting is as follows; “… I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country…” (Poe, The Fall 38). There is no mention of country, town, or place, the house itself is alienated from any sense of society. In her article “The Self, the Mirror and the Other: ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’,” Renata R. Mautner Wasserman writes:

The description of the House of Usher stresses its isolation… From the outside, the house is enveloped in an atmosphere ‘which had no affinity with the air of heaven’ and surrounded by a tarn which, like a moat, separates it from the rest of the world. (34)

The house embodies that of the alienated. Further descriptions of the house also personify it, referring to “vacant eye-like windows” (Poe, The Fall 38). This results in the house becoming an allegorical reflection of Roderick and his malady, and Roderick as a reflection of the decaying house. The decay of the house and Roderick are reflections, and so too is its alienation.

Within the house is a library whose books are also allegories for the occupants. It is Roderick’s studio that acts as his personal ‘library’, where he keeps his most prized books that he reads in his final days. To even reach this part of the house the narrator travels through many labyrinthine corridors; “… I entered the Gothic archway of the hall. A valet, of stealthy step, thence conducted me, in silence, through many dark and intricate passages in my progress to the studio of his master” (Poe, The Fall 40). The room itself is described in such a way that reinforces its disconnection from the outer world. Wasserman also says the following:

From the inside, the windows in the room where Roderick spends most of his time are ‘at so vast a distance from the black oaken floor as to be altogether inaccessible from within’ and do not fulfil the usual function of allowing even the most elementary of exchanges between Usher and the world: a look from within and light from without (only ‘feeble gleams of encrimsoned light made their way through the trellised panes’ (34)

The library is located deep within the house, it is the most privatised part of the house where Roderick chooses to isolate from the world.

Within the library are thirteen books mentioned by name. These books have varying themes from the utopic to the unholy and demonic. Thomas Ollive Mabbott in The Books in the House of Usher (1973) comments on the intentional implementation of the books saying:

…the peculiar care with which Poe prepared his stories—among which “The Fall of the House of Usher” is pre-eminent for elaboration and perfection of detail— seemed to argue that here, of all places, Poe would not have violated his own dictum against the introduction into the perfect tale of any irrelevant or purposeless word. And an examination of the books referred to has amply justified my belief in the conscious use of every book… (3)

Mabbott suggests that Poe likely knew a great deal about these books, hence their inclusion. As Poe himself stated, “A short story must have a single mood and every sentence must build towards it” (Poe, “The Philosophy” 153). The books and their names were implemented for a specific purpose within the story and the allegory. The reader only reading the titles, in brief, can make an assumption about the contents of the books based purely on the fact they do not sound normal, setting them apart as alienated. The obscure, mysterious and occult names of the books have the power to affect the reader. Roderick’s obsession with these books

alienates him from the norms of society further. The act of reading a book is an inherently individualised task too. One places themselves into a story or world that is not their own, they separate themselves further from reality and the outside world. This completes the multilayered allegory of alienation. The books, the occupants, and the house are one and culminate in a story that describes the ramifications upon the individual who should become alienated.

3.1 INTRODUCTION

3.2 ALIENATION

Alienation

Alienation in Architecture, the House and Home

The Alienated Self and Other

Project Review

3.3 ARTIFACT

Artifacts

Artifacts and Alienation

Project Review

3.4 DIALECTIC DIALOGUES

Dialectic Dialogues

Curation and Collections of Artifacts

Curation of Context

Project Review

3.4 TEMPORALITY

Temporality and Dialectic Chronotopes

Alienation and the Chronotope

Architecture, Decay, and Temporality

Project Review

3.5 CRITICAL REFLECTION

The literature and project review chapter reflects upon key theorists and case studies, interrogating them to address Poe’s literary framework and the thesis’s Research Aim and primary Objectives. These theorists and case studies build a theoretical foundation for addressing the research question and progressing the design-led investigation to follow.

From childhood’s hour I have not been as others were—I have not seen as others saw—I could not bring my passions from a common spring.

-Edgar

Allan Poe, Alone

Section 3.2 reflects upon alienation, alienation within the built environment and then finally how this is expressed through concepts like the Self and Other within Poe’s short story resulting in an allegorical understanding of alienation. This section relates primarily to the Research Aim of the investigation:

RA. Alienation to investigate how an allegorical architectural project can be used as a critical method to enhance understanding of the individual’s alienation from society, and the role the house can play in that relationship.

The principal theorists and case studies relating to the RA are:

Key Theorists:

- Rahel Jaeggi, Professor of Social and Political Philosophy at the Humboldt University of Berlin.

-Jonathan Hill, Professor of Architecture and Visual Theory at the Bartlett School of Architecture.

- Alasdair MacIntyre, Philosopher.

- Renata R. Mautner Wasserman, Professor at Wayne State University.

Key Case Studies:

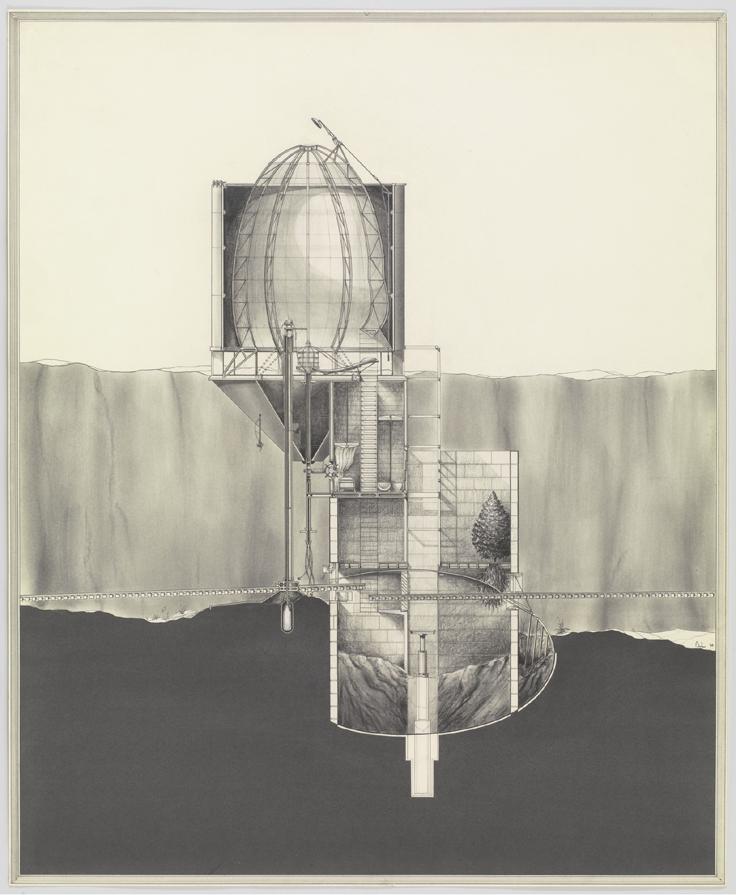

-Oxygen House by Douglas Darden, 1988.

-The Flood House by Matthew Butcher 2004.

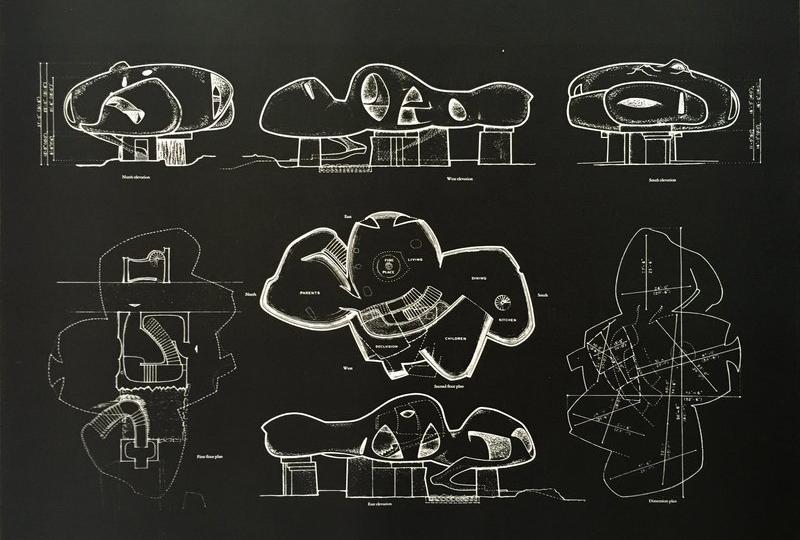

-Endless House by Fredrick Kiesler, 1958.

First and foremost, it is crucial to identify and define what alienation is. The Encyclopaedia of Britannica defines alienation as follows; “alienation is, in social sciences, the state of feeling estranged or separated from one’s milieu, work, products of work, or self”. The word milieu and its etymology are of interest too. In Old French mi means "middle", and lieu means "place". The Encyclopaedia of Britannica’s definition of Milieu is “the physical or social setting in which something occurs or develops: environment”. In her book Alienation (2014) Rahel Jaeggi describes alienation as follows:

Alienation means indifference and internal division, but also powerlessness and relationlessness with respect to oneself and to a world experienced as indifferent and alien. Alienation is the inability to establish a relation to other human beings, to things, to social institutions and thereby also – so the fundamental intuition of the theory of alienation – to oneself. An alienated world presents itself to individuals as insignificant and meaningless. As rigidified or impoverished, as a world that is not one’s own, which is to say, a world in which one is not ‘at home’ and over which one can have no influence… The alienated person, according to the early Alasdair MacIntyre, is ‘a stranger in the world that he himself has made’. (3)

Jaeggi’s description has been selected here as alienation to many is a topic of the past, having already been thoroughly commented on by the likes of, Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel. Jaeggi adds a contemporary take on alienation that considers multiple foundational theorists and their theories on alienation, such as Marx and Heidegger. Jaeggi’s description of alienation was also selected as I find the distinction of “not at home” (3) interesting. She specifically uses the term home to describe the antithesis of alienation.

Home need not necessarily be associated with the built environment. One could be said to be at home without having a permanent residence or even a house at all, and even within the built environment not every house is necessarily considered a home. What is important for this discussion though is that more often than not, the term home is related to the house, and it is through the built environment in which they exist that can allow its user to isolate. Jonathan Hill in Immaterial Architecture (2006), explains how the house which began traditionally as a public-orientated space has over time become privatised:

Home is the one place that is considered to be truly personal. Home always belongs to someone. It is supposedly the most secure and stable of environments, a vessel for

the identity of its occupant(s), a container for, and mirror of, the self. However, the concept of home is also a response to the excluded, unknown and unpredictable. Home must appear solid and stable because social norms and personal identity are shifting and slippery. It is a metaphor for a threatened society and a threatened individual. The safety of the home is also the sign of the opposite, a certain nervousness, a fear of the tangible or intangible dangers outside and inside. The purpose of the home is to keep the inside inside and the outside outside. (8)

An important distinction to make is that the private areas of the house remain important, the safe spaces they create for the occupant should remain that way. The criticism here is instead on the cases in which complete alienation takes place. I am also not suggesting the model of the house should revert to that of the medieval times either. However, it is an important distinction to make that this shift has happened and that the state of the house in current times is privatised leading to a space in which the alienation of the individual can occur. The point Hill makes is that there are nonnormative approaches to conceive of architecture and the house, which lead to unexpected outcomes that benefit the current state of the house.

I would like to draw specific emphasis back to the following line from Hill’s discussion, “[Home] is a vessel for the identity of its occupant(s), a container for, and mirror of, the self” (8). According to Hill, the home is a reflection of its occupant, and this is what we find within the The Fall. Roderick surrounds himself with material objects and belongings from generations past that are reflections of Self, including his books. The Usher House and its contents are all a reflection of Roderick, hence Self. In her article Wasserman discusses the relationship and importance between Self and Other within the story, writing:

“The Fall of the House of Usher” records the difficulty of accepting the necessary and true Other in preference to what simply reflects one’s own self. In it Poe gives fictional form to the fundamental conflict between reluctance to give up oneself and what is most like and most familiar to oneself, and the social cultural necessity for doing so. The absolute refusal to enter into relations with the Other is death, the fear of which haunts Roderick and prompts him to call the narrator in a last effort to avoid his fate. (33)

Wasserman goes on to write:

Though… he avoids the dangers of an encounter between self and Other, [Roderick] is in the same process erasing the line that, by marking the difference between the natural world and the society of men, defines him as human. At the last minute, in an effort to re-establish relations with another and redraw the line, Roderick summons his childhood friend, the narrator. But the process apparently has gone on for too long, for it proves to be irreversible. (34)

Poe’s allegory is that refusing the connection between Self and Other, results in negative consequences for the Self. In the words of Jaeggi this would lead the individual to a world that seems insignificant, meaningless, rigidified, impoverished, and ultimately a world that is not one’s own. Reflecting on both Wasserman’s and Hill’s theories, not only does Roderick sever his connection from Self and Other through physical isolation from the world; the place, the Usher house, and its objects, the books, in which he does are also a reflection of Self. Therefore, establishing that the house is key in the relationship to Roderick’s disconnection of Self from Other, and hence alienation.

Oxygen House is a speculative house intended for its one occupant, Burden Abraham. The architecture and its client are based in the realm of fiction. The accompanying narrative explains how the house is situated on the site of the nearly fatal wound that paralysed Abraham and left him needing a breathing apparatus. Abraham requests a house to be built, that includes an oxygen tent, with the intent of being entombed within his house upon his death. In this way, he is chained to the house and its interior through the reliance on the breathing apparatus. He is to become seemingly isolated from the world within the walls of the house, both in life and then beyond.

The house in this case is quite literally a mirror of Self, and the boundaries that exist between the interior and exterior, are crucial to the design. Like the Usher house and Roderick, the occupant and house become one through isolation and dependency on interiority, and finally through the metamorphosis upon death. In many ways, Darden’s project parallels Poe’s. It serves as a key case study in isolation from the outside and how speculative architecture can be conceptualised to allegorically reflect its occupant and some larger idea beyond the standard expectation set by the design of a house.

Hill discusses Matthew Butcher’s Flood House as a case study that adapts the normative approach to the design of the house, specifically the isolation that comes with it (195). Hill states, “… Matthew Butcher design houses that accommodate a public and a private life, questioning the long isolation of the home” (195). As with Darden, Flood House challenges the preconceptions of how a house operates, breaking away from the now standardised model, as raised by Hill. The Flood house is described by Hill as follows:

The Flood House does not oppose fluid forces with inflexible barriers. Immersed in a constantly evolving system, as boundaries shift and blur, fluctuations in climate, matter and use are its subject and fabric. Analogous to the environment it inhabits, The Flood House records and responds, expands and contracts, reconfigures and adapts according to the tides, seasons and users. What is inside one moment may be outside the next. (199)

As Hill comments, “It suggests that a feisty dialogue between the user, building and environment may be more stimulating and rewarding” (200). Changing and adapting the relationships that exist within the realm of the house can lead to a more fruitful experience for the user. It is through investigations, such as Butcher’s, that begin to result in conceptions of the house that challenge the modern-day model, one that could be implemented to combat alienation.

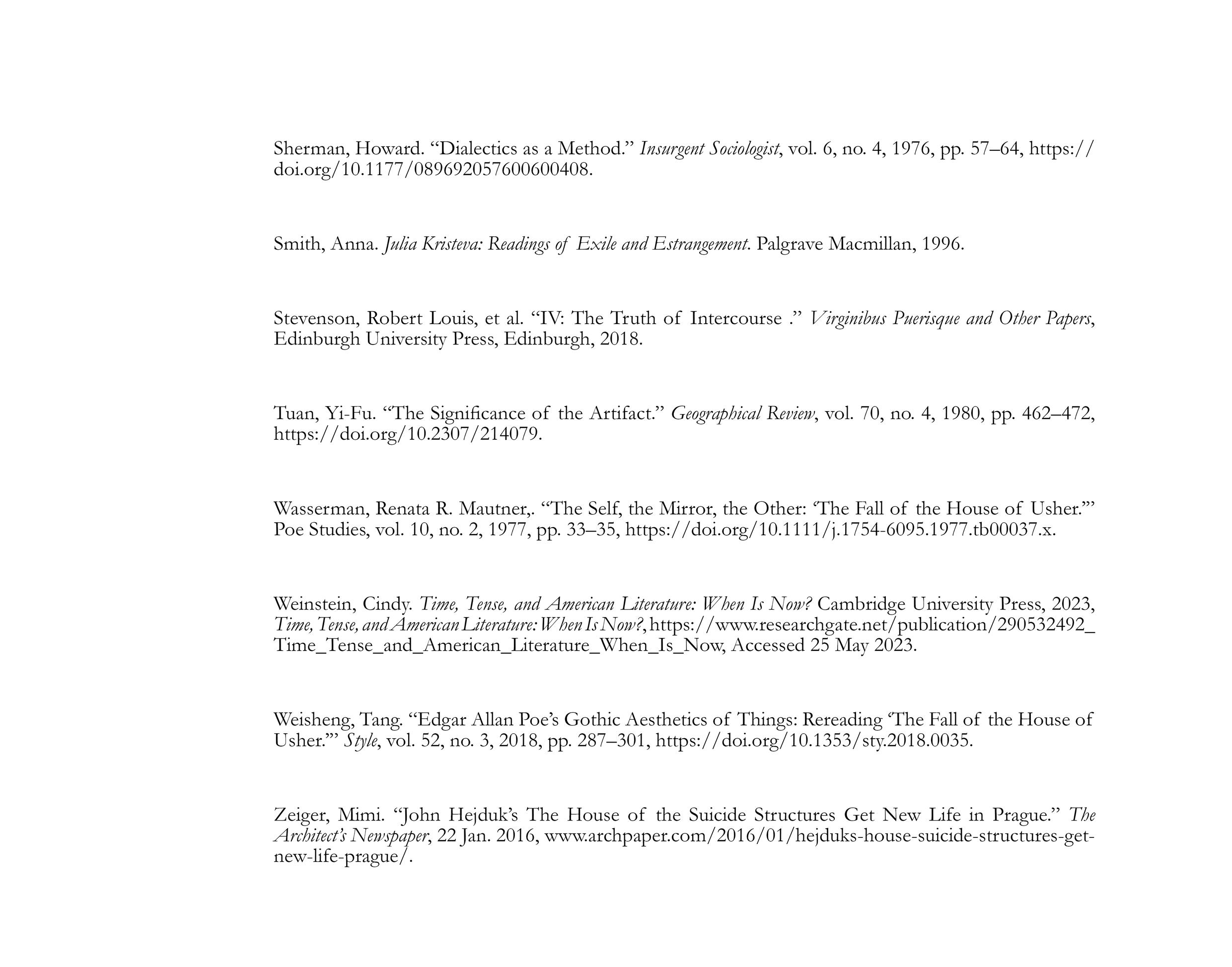

Another unconventional speculative residential project is Fredrick Kiesler’s Endless House. The house embodies the term he invented ‘correalism’, which refers to the relationships between space, people, objects, and their connections (Kiesler, 148). He intended it to oppose the modernist functionalism movement of the time with its stark square boxes that he saw as inherently inhuman. In his book Frederick Kiesler 1890-1965: en el interior del endless house = inside the endless house (1997), he describes the house as follows:

The Endless House is called the ‘endless’ because all ends and meet continuously. It is endless like the human body. There is no beginning and end to it… All ends meet in the ‘Endless’ as they meet in life. Life’s rhythms are cyclical. All ends of living meet during twenty-four hours, during a week, a lifetime. They touch one another with the kiss of time. They shake hands, stay, say goodbye, return through the same or other doors, come and go through multi-links, secretive or obvious, or through the whims of memory. (148)

Kiesler refers to the rooms as if they are extensions of the occupant’s limbs. The house and its occupant are one, similar to the allegorical relationships present in The Fall. Through the architecture, the occupant’s connection and correalism are reinforced. Although not specifically intended as a response to alienation or disconnection as such, the Endless House is seemingly the antithesis of these notions, hence serving as an interesting example of an intervention that addresses connectivity in the domestic built environment. The intent is that by reflecting on these houses and their nonstandard approaches to achieve nonstandard houses, like Poe’s literary house, so too could be conceived an architecture that addresses alienation on the domestic scale through a nonstandard approach, and in Hill’s words an intervention that is “more stimulating and rewarding” (200).

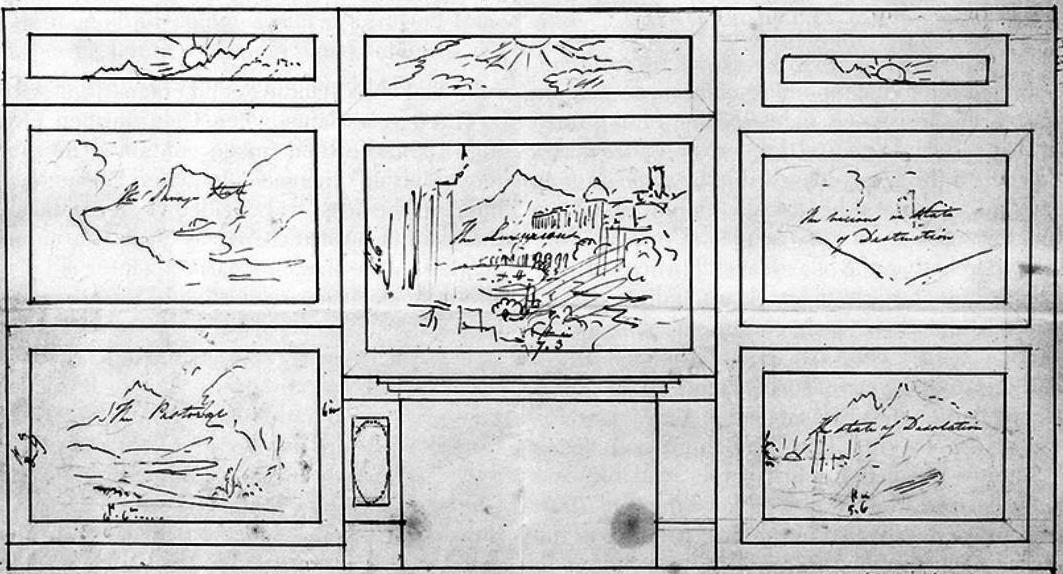

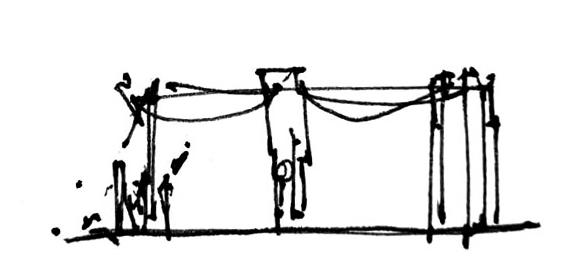

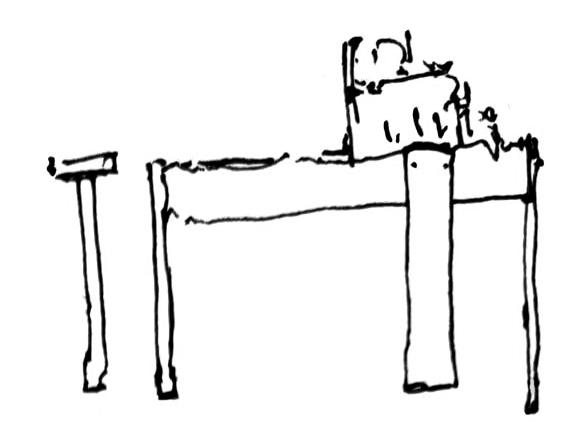

Fig. 3.4

Endless House Drawing, Fredrick Kiesler, 1958.

“The artifact—city, building, painting, whatever—has then, in the best sense, its own double obligation. It may act as a positive instrument for the qualification of human association (artifact as in-between ‘table’) and at the same time it may in itself present an encapsulation of the same uncertain drama of reality which it helps to qualify and stimulate. The artifact, in other words, may operate as both active agent and as a means of record-keeping, occupying a realm which is both 'immediate’ and potentially timeless.

-Fred Koetter, “Notes on the In-Between”

Section 3.3 reflects upon artifacts as fundamental affective literary tools within The Fall, as well as the wider world. It presents theories relating to the artifact’s role as affective and capable of communicating allegory, specifically that of alienation. It relates primarily to RO1 of the investigation:

RO1 Artifact

to explore how theories relating to Artifacts can be used to create a context for an allegorical understanding of alienation.

The principal theorists and case studies relating to the RO are:

Key Theorists:

-Yi- Fu Tuan, Professor of Geography at the University of Minnesota.

-Tang Weisheng, Professor at the Faculty of English Language and Literature at Guangdong University.

-Richard Heersmink, Assistant Professor at the Department of Humanities and Digital Sciences and Department of Philosophy at Tilburg University.

Key Case Study:

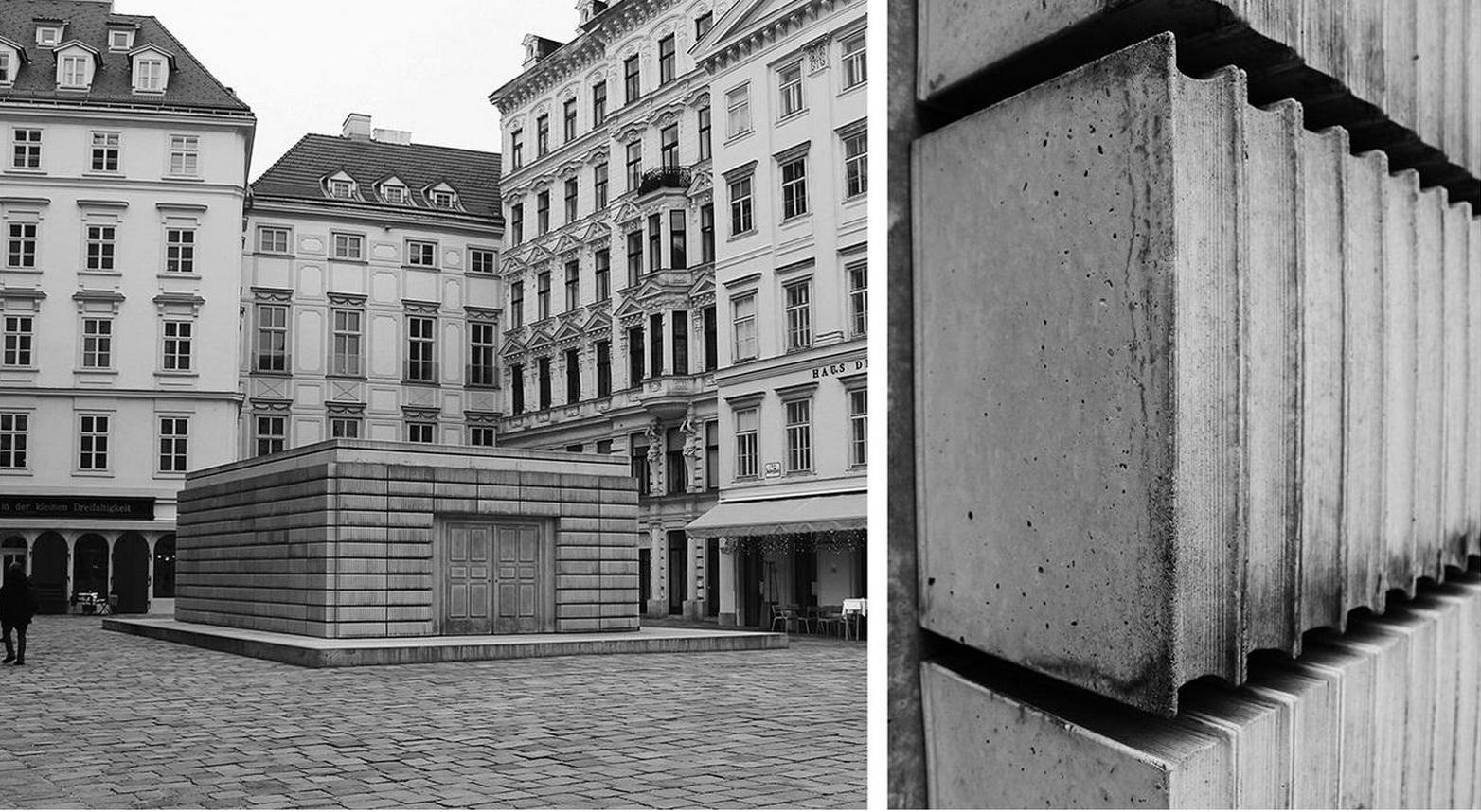

-Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial by Rachel Whiteread, 2000.

The artifact is used within Poe’s framework to establish and define what is Self and what is Other within his story, and ultimately to achieve his allegory of alienation. Yi- Fu Tuan in “The Significance of the Artifact” (1980) acknowledges that it is commonplace for the artifact to be prescribed a definition of an object that can be placed within a museum or gallery, one of a purely material and typically smaller typology. The word artifact can however be applied in a more general sense as Tuan states:

An artifact, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is a thing made by art, and the word art connotes skill. An object made with skill, that is, through knowledge and practice could be a poem, an axe, or a house… much of the significance of the artifact would be lost unless we retain also its broad sense as a humanly constructed object, material or mental. (462)

With this definition in mind, there are numerous objects mentioned within the story that we can define as artifacts from paintings, instruments, furniture, books, and even the house itself. Tang Weisheng in “Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic Aesthetics of Things Rereading ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’” (2018), refers to “things” that for all extensive purposes will be referred to here as artifacts, as defined by Tuan. Weisheng identifies the artifacts Poe implements in the story to drive the narrative forward saying, “…rather than just a background for human actions, things in ‘The Fall’ are themselves actors, which possess souls and power, and are taken advantage of by Poe to drive his narrative to progress from the beginning to the end…” (288). Developing this further, Richard Heersmink in “Varieties of Artifacts: Embodied, Perceptual, Cognitive, and Affective” (2021), like Tuan, defines the artifact in a broader sense as objects that “come into existence through human agency” (573). Within this scope exist four categories of artifacts; perceptual, embodied, cognitive, and affective; additionally, artifacts may also belong to multiple categories depending on what they are and how they are used. The most relevant for this discussion though is affective artifacts, defined by Heersmink as follows:

Emotion is traditionally conceptualized as a purely internal and biological affair. Most emotion theorists and psychologists focus on emotion as instantiated in the biological body. However, Paul Griffiths and Andrea Scarantino recently pointed out that ‘Emotion is a form of skilful engagement with the social environment that involves a dynamic process of negotiation mediated by reciprocal feedback between emoter and interactants’. Griffiths and Scarantino focus on emotional aspects of social interactions, but interactions with artifacts also have an emotional and affective component. (582)

Within what Heersmink calls the landscape of affectivity are emotions, moods, sentiments,

temperaments, and character traits. Of note are the emotions of fear and sadness, moods of the blues and anxiety, and temperament of melancholy. What is crucial from Heersmink’s description is that artifacts have emotional and affective capabilities and can be specifically related to and evoke mentalities such as fear, sadness, anxiety, and melancholy. Bringing the discussion back to Hill once more who stated that the house is “a vessel for the identity of its occupant(s), a container for, and mirror of, the self” (8), we can further define these artifacts in The Fall also as affective for Roderick. The artifacts are both part of Roderick as well as define him as a person.

With a definition, the affective capability of artifacts, and a link to The Fall established, we can now relate this to alienation through Tuan’s theory of artifacts within the house. Tuan states:

The house in many societies is a microcosm that encapsulates with clear and graspable detail what the larger world is like and how we should behave in that world. The house imparts lessons implicitly, without demands on conscious thought, artifacts do not normally raise puzzling questions. Why should they? After all, they are the products of human minds and skills. (471)

Not only are artifacts and the house a reflection of the individual, but this too is typically a reflection of wider society, displaying what the larger world is like and how one should act in it. This could for example be, books, artworks, furniture, among any other typical objects one expects to find within the house. The Usher house does contain these artifacts but is the antithesis of Tuan’s suggestion of how they should typically act within the house. For example, furniture has been within the house for generations and is uncomfortable and tattered, artworks are obscure and only related to the Usher family, the books are those of the occult, the house is a decaying gothic mansion, and so on. The artifacts are set apart from society in what is considered normal, they raise questions and do not impart what the wider world is like through their sole mirroring of the Self, they are inherently alien in contrast to the wider world. Therefore, it is through the artifact that we can begin to understand Poe’s allegory of the alienation of the individual from society.

Rachel Whiteread’s Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial is a key case study in the fusion of traditional artifacts and architecture. The memorial consists of an inverted library, with cast books cladding the exterior, the spine facing inward. The structure contains a pair of doors that cannot be entered. It memorialises the lost lives of the Austrian Jewish community in the war. As Rachel Carley states in “Silent Witness: Rachel Whiteread’s Nameless Library” (2010), “In Jewish tradition the first memorials came in book form, and Whiteread’s memorial makes reference to Jewish people being the people of the book” (27), further saying, “The memorial’s power lies precisely in its ability to disturb distinctions between architectural typologies, between interiors and exteriors, rendering the familiar strange” (28). The nameless books become affective allegorical artifacts applied to architectural form that challenge architectural typologies as well as unconventional applications of artifacts.

In Poe’s story, artifacts collectively mirror the Other. Carley identifies that here they represent loss and a people saying, “The books on the memorial make reference to a knowledge base that has been eradicated, alluding to the stories unable to be told, just as the lives of the authors were stopped short” (31). Jewish people being the people of the book along with the countless books that burned at the hand of Nazis during the war gives the book its affective power within the design. No one book is more important than the next in the memorial, and it is the collective of these artifacts that tell the story of the people and site, and the deeper meaning through what they represent allegorically. Through architecture that is simultaneously interior, exterior, and inaccessible; in combination with books that are unreadable and indistinct, preconceptions of both are challenged allowing the viewer to contemplate their meaning and significance. Thus, gain an understanding of the people and books the memorial represents.

Curators, designers, and educators shape exhibitions, and exhibitions shape the way that visitors engage with art and artifact.

- Steven D. Lubar, Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present

Section 3.4 reflects upon Dialectic Dialogues between artifacts that create relationships that convey an overarching allegory that is more than the sum of its parts. This section also reflects upon theory relating to curation in the selection and presentation of artifacts to create Dialectic Dialogues. It relates primarily to RO2:

RO2 Dialectic Dialogues to explore how Dialectics can be applied to Artifacts in creating relationships and dialogues that convey the allegory of alienation.

The principal theorists and case studies relating to the RO are:

Key Theorists:

-Howard Sherman, Professor of Economics at the University of California.

-Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Philosopher.

-José Duarte, PhD graduate and assistant professor at the University of Lisbon.

-Steven D. Lubar, Professor of American Studies at Brown University and former museum curator and director.

Key Case Studies:

-The Course of Empire by Thomas Cole 1836.

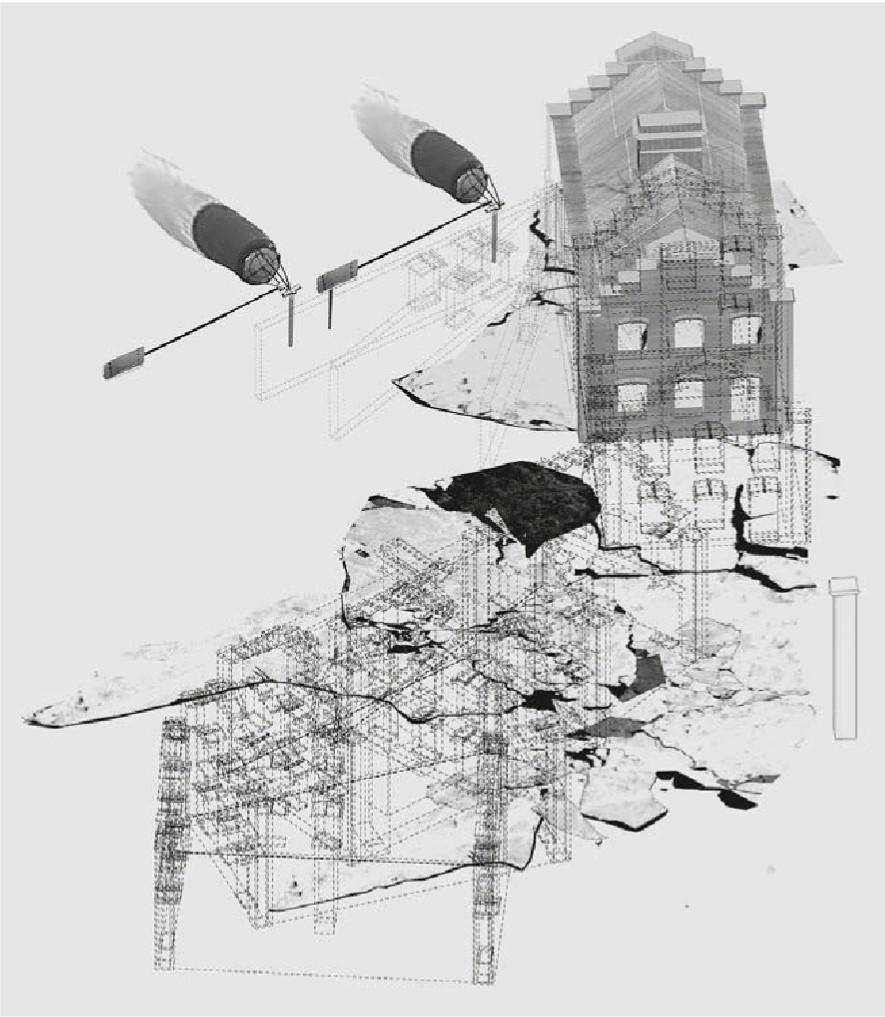

-The House of the Suicide and House of the Mother by John Hejduk, 2016.

Howard Sherman in “Dialectics as a Method” (1976) defines the concept of dialectics as follows, “… ‘dialectics’ means an approach to problems that visualizes the world as an interconnected totality undergoing minor and major changes due to internal conflicts of opposing forces” (57). Poe conveys his allegory of alienation by including opposing forces in The Fall. Dialectic relationships exist at multiple levels, the primary focus for now is on the artifacts that form the foundation of dialectics within the story, and later dialectic temporality.

The theory of dialectics is long-running and multifaceted within philosophy, with a multitude of differing specificities, for example, Hegel’s initial idealist dialectic theory compared to Marx’s more materialist approach. The holistic concept of dialectics does remain consistent throughout these various applications though. For this thesis Hegel, who initially coined the term dialectic, will be applied; stating that a concept is only defined by its opposite (Sherman, 57). This in a basic sense is what Poe applies within The Fall. Through the defined set of artifacts and the introduction of the narrator, a dialectical relationship is established. It is the dialectic dialogue between these two oppositions that we can conceive of the allegory of alienation. The artifacts, the house and Roderick are all reflections of Self, while the narrator is Other, the dialectic opposite. Assuming the position of the narrator, the reader understands the artifacts as being nonnormative and opposed to their conception of ‘normal’, and most importantly the societal preconception of normal that Roderick has become disassociated with. One example from The Fall is as follows, "The general furniture was profuse, comfortless, antique, and tattered. Many books and musical instruments lay scattered about, but failed to give any vitality to the scene" (Poe 40). This example expresses how from the narrator’s position the artifacts are in opposition to some other expectation or norm, forming the dialectic dialogue. It is only through this juxtaposed relationship and dialectic that we come to understand the artifacts and therefore Roderick as alienated from the narrator, or Other, and hence society.

José Duarte in “The House of Usher and The House of Fisher: Towards an Architecture of (Dis)comfort” (2010), discusses the haunted house trope within The Fall saying, “The haunted house had been a repository for centuries of memories and traditions like a museum full of objects that oscillate between life in death and death in life” (67). The Usher house and its artifacts parallel that of a collection within a museum, with each having its own story and playing its own role. Curation theory will be examined as a part of Poe’s framework in how he achieved his allegory of alienation through the careful curation of artifacts. Steven D. Lubar in his book Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present (2017), states:

… museums are places that tell stories… The artifacts have stories, and the exhibit curator’s job is to put those objects and their stories together in a way that tells a larger story. Or more precisely, in a way that allows visitors to learn, experience, engage with, and explore the museums art, artifacts, and specimens, to see them, and the rest of the world, in a new way. (152)

It is in this way that Poe becomes a sort of curator of the artifacts within The Fall, using the artifacts to allow the reader to engage with the allegory of alienation. Not only are the specific artifacts and their stories important but also their relation to one another. Lubar discusses the importance of the object placed in a collection to achieve an overarching larger story, using the John Whipple Potter Jenks Museum and Jenks’ ideology as an example, saying, “The objects he collected reflected his belief in natural theology: the glories of nature reflected the glory of God. A visit to the museum was, Jenks believed, an opportunity for a religious experience” (16). Each of Jenks’ artifacts tells its own story but holistically another as a collection. Further expanding on this Lubar states:

That bigger picture is different for different museums. It might be, as it was for Jenks, a religious story. It might be political, social, or cultural. It might be the story of a town or a nation, an art movement, or the natural world… all museum collecting has this in common: to use the artifact to tell a bigger story. The way museums do that is to move things out of their natural habitat and put them in a place where both the things themselves and the information about them can be preserved and used in a new way. Museums give artifacts a new life, a new meaning. The new life is as part of a collection that tells that larger story. (16)

What Lubar is saying is that not only are artifacts themselves important but how they are curated as a part of a collection will affect the larger story they tell, which itself can and will vary. This is an important distinction for the use of artifacts and their curation within Poe’sPut the right things next to each other, in the right order, offer visitors the right kinds of opportunities to interact with them, provide thought-provoking advice and information and direction, and a rewarding, pleasant place to wander, and you move beyond making an argument. You allow for thoughtful conversation, for significant engagement, for the making of meaning. (159)

Poe implements within his framework most if not all these elements of curation of context and artifacts in a dialectic relationship that is the foundation for the reader to derive the allegory of alienation and its meaning within The Fall

The context in which artifacts are presented is also of great significance to their curation, and how they are understood by a viewer, as Lubar explains:

The museum assists our imagination by offering intellectual and physical contexts. Intellectual context is the system, order, and overall meaning: the big picture. Physical context is how objects are put on display. The art of exhibition is deciding how to combine these two types of context to… allow visitors to use their imagination. (153)

This relates to several contextual elements from the type of museum, the description of the object, accompanying artifacts, the type of exhibit, and so on. This like the curation of the artifacts is dependent on thelarger story that is being told by the curator. Lubar continues with the following example, “The Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, and the new Met Brauer may show similar art, but each displays it differently to tell different stories. The same object might be shown in an art, history, or anthropology museum to make different points…” (156). Applying this to Poe’s framework, not only is the curation and collection of artifacts important, but so too is the context, or rest of the story, in which they appear. Although not directly transposable to literature the intellectual and physical contexts suggested by Lubar can still be applied here. Intellectual context can be likened to that of the writing style of the story, the language used, and the construction of sentences and paragraphs in the formation of context. For example, through the implementation of certain terminology such as, ‘bleak, ‘melancholic’, etc, the reader is provided a context for the story and its artifacts, and therefore the allegory. The connotation given to, and context associated with, The Fall is therefore negative. The physical context can be likened to the artifacts themselves and the setting of the story, which has already been discussed prior. Collectively, both contexts and the artifacts have been curated to ultimately evoke the reader’s imagination and convey the allegory of alienation to the reader. This being said there comes with artifacts and contexts multiple meanings and interpretations with every viewer, which Lubar also addresses, “… objects are not simple things nor do they reveal simple truths. They carry many meanings and can tell many stories” (164). Further saying, “This doesn’t mean that visitors will follow your arrangement, or that the ideas in your head will be magically transferred to the heads of the visitors” (160). Poe’s story is allusive and mysterious enough that it engages the reader’s imagination and can lead to a vast number of readings, of which alienation is just one. But the intent is that the curation provides enough evidence for the reader to derive the intended meaning, in this case, the allegory of alienation. This section and the metaphor of the story as a museum can be aptly summarised by Lubar:

Put the right things next to each other, in the right order, offer visitors the right kinds of opportunities to interact with them, provide thought-provoking advice and

information and direction, and a rewarding, pleasant place to wander, and you move beyond making an argument. You allow for thoughtful conversation, for significant engagement, for the making of meaning. (159)

Poe implements within his framework most if not all these elements of curation of context and artifacts in a dialectic relationship that is the foundation for the reader to derive the allegory of alienation and its meaning within The Fall.

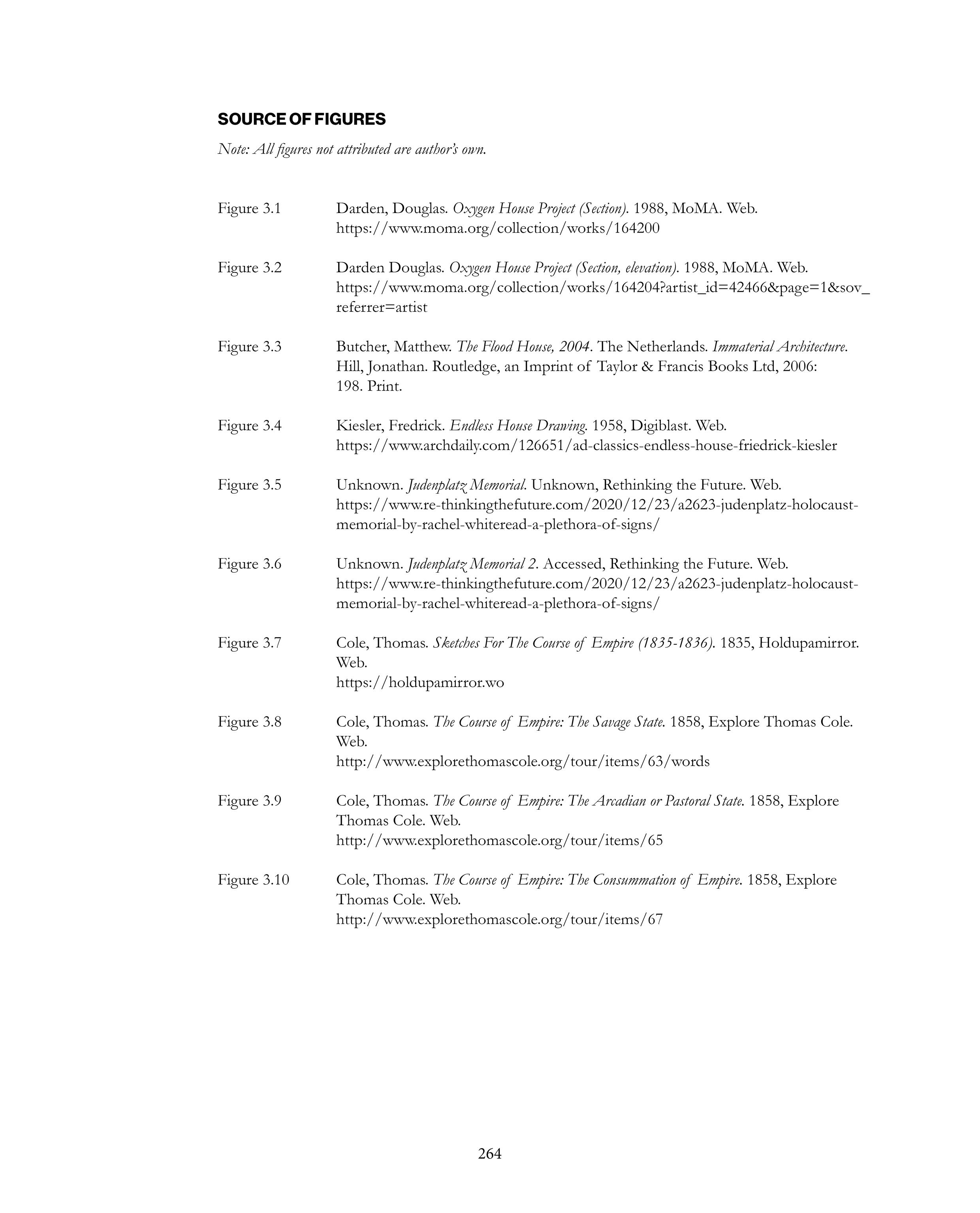

The Couse of The Empire is a series of five paintings by Thomas Cole. They illustrate change of a landscape through the rise and fall of an empire. The names of the paintings are as follows; The Savage State or The Commencement of the Empire, The Arcadian or Pastoral State, The Consummation, Destruction, and Desolation. Each of the paintings is evocative, but it is the relationship and dialogue between them that makes them most affective for the viewer. Ellwood Parry in “Thomas Cole’s “The Couse of Empire” a Study in Serial Imagery” (1970) explains the dialectic dialogue that each of the paintings holds in their arrangement:

The reviewer… understood perfectly the basic aesthetic contrast between the sublime and the beautiful that Cole wanted to embody in the opening pair of his series. This expressive contrast would have been reinforced by the installation. Cole planned to hang the Savage State directly above the Pastoral State, so that the turbulence of one would complement the stability of the other. Likewise, the stormy and dramatic fourth picture, Destruction, was designed to be hung directly above Desolation, the last of the set, which remains serene and beautiful (if somewhat melancholic) in effect. (77)

Not only is the consideration of the series as a whole important but also their specific placement against one another for how the viewer interprets their deeper allegorical meaning through juxtaposition in the scenes before them. Each is an artifact that builds to create a larger meaning than their individual one, as is the case with Poe’s artifacts and books.

Fig. 3.8

The Course of Empire: The Savage State, Thomas Cole, 1858.

Fig. 3.9

The Course of Empire: The Arcadian or Pastoral State, Thomas Cole, 1858.

Fig. 3.10

The Course of Empire: The Consummation of Empire, Thomas Cole, 1858.

Fig. 3.11

The Course of Empire: Destruction, Thomas Cole, 1858.

Fig. 3.12

The Course of Empire: Desolation, Thomas Cole, 1858.

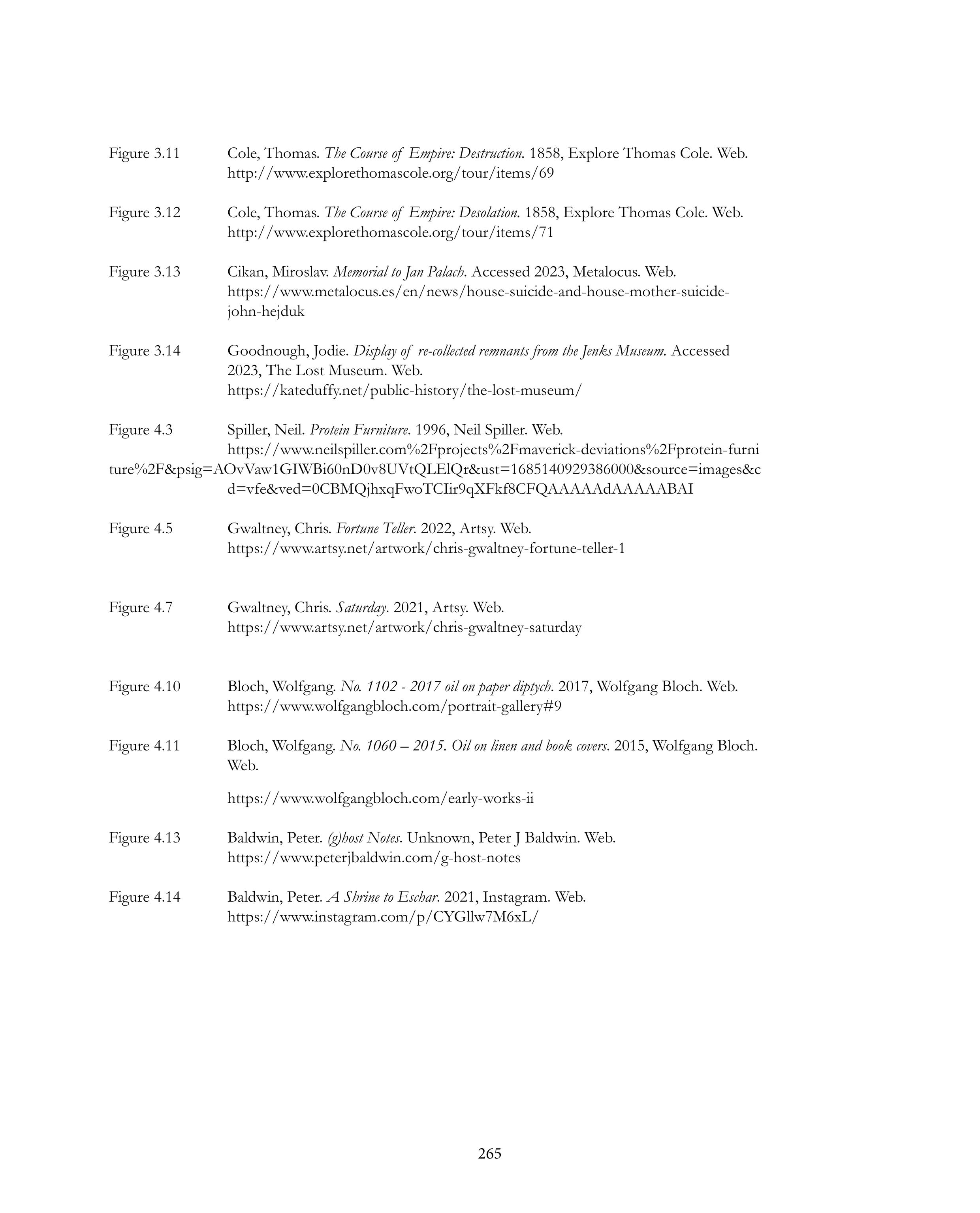

BY JOHN HEJDUK, 2016.

The House of the Suicide and House of the Mother is a memorial by John Hejduk honouring Jan Palach, who protested the government through an act of self-immolation in 1969. It is based on the poem The Funeral of Jan Palach by David Shapiro. The design consists of two spaces that sit in opposition to one another. The House of the Suicide represents Palach, in stainless steel, and the House of the Mother representing his mother, in corten. There is a range of dualities and dialectic dialogues between the two structures, from their materiality, accessibility, and the spiked forms that adorn them, to what they represent. The materiality of House of the Mother describes decay through its rusting surface, while The House of the Suicide remains pristine and immortalised without decay in stainless steel. The House of Suicide is sealed off and inaccessible while its counterpart is accessible and allows the user to view the opposing structure. The spikes of each are described by Hejduck’s daughter, Renata Hejduk as follows:

My father thought of the spikes as a sunburst, as sonic—the mother is quiet and turning in on herself. Implosion of sound and explosion. The sonic act when Jan dies is his sound going out into the universe as an act against the apathy of the students in 1968. He set himself on fire to set them on fire. (qtd. in Zeiger)

What the structures represent also sit starkly opposed, one the child and the other the mother who has outlived their child, life and death. All elements culminate in a dialectic relationship that tells the story of mother and son, and ultimately allegorically the political angst between the public and government of the time. From early sketches, it is presumed that originally Hejduk only planned for there to be The House of the Suicide. While this would have still been impactful as a memorial and still conveys a lot of the same meaning, it is through the dialectic relationship the two structures form that gives them their ultimate poignant affect for the viewer.

Section 3.5 reflects upon Temporality as fundamental in establishing Dialectic Dialogues between Artifacts that create and reinforce the allegory of alienation. Literary theory relating to chronotopes is reflected upon. Finally, the purpose of ruin and decay within the built environment is reflected upon, and how they can reinforce types of temporalities to achieve allegory. It relates primarily to Research Objective three:

to explore how architectural theories relating to temporality can provide an allegorical architectural context representing the decay of artifacts over time and their relationships with one another in expressing the allegory of alienation.

The principal theorists and case studies relating to the RO are:

Key Theorists:

-Rachel Boccio, Professor in the Writing department at the University of Rhode Island.

-Mikhail Bakhtin, Philosopher, literary critic, and scholar.

-Cindy Weinstein, Professor of English at the California Institute of Technology.

-Juhani Pallasmaa, Architect and former professor of architecture and dean at the Helsinki University of Technology.

Key Case Studies:

-Oxygen House by Douglas Darden, 1988.

-The Flood House by Matthew Butcher, 2004.

-Judenplatz Memorial by Rachel Whiteread, 2000.

-The Lost Museum Exhibition by Jenks Society for Lost Museums, 2014.

Temporality is key to the story of The Fall. Rachel Boccio in “The Things and Thoughts of Time Spatiotemporal Forms of the Transcendent Sublime in ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’.” (2017) identifies temporality as part of Poe’s framework at both the writer scale and narrative scale. Commenting on the short story structure itself Boccio states, “Central then to Poe’s liberating aesthetic is the mystical power of spatiotemporal limits: limits on the length of a sentence, the length of a composition, the length of a reader’s attention span. Poe utilized the temporality of short forms, their concentrated physical nature and reliance on pacing, to experiment with temporal disorder” (56). Not only this but the structure and vocabulary of the writing reinforce this, Boccio further saying, “Nearly every other sentence in ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ is punctuated by the indices of time. Strung together, the sentences construct a narrative that is thematically and textually about the movement through space in time” (60). Temporality is at the core of how Poe constructed and structured the story, but it is also a literary narrative feature within the story. Boccio introduces two Bakhtinian concepts of time within the literature, stating “Temporal disjuncture in ‘The Fall of House of Usher’ is signified through key chronotopic images: the castle and the road” (56). Mikhail Bakhtin initially established these two chronotopic terms in “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel” (1981). Boccio succinctly defines Bakhtin’s castle-time as “a time of circularity, of endless repetitions, of return” (61), and road-time as “ordered, sequential, knowable, passing away” (61). Within these two temporal operations, Boccio establishes that the narrator operates as, or on, road-time saying, “The storyteller, sane of mind and normal in sensibility, is saved from dissolution and impossibility. He is kept firmly grounded on the narrative road, progressing chronologically into the future” (55). The Usher house and its contents, on the other hand, operate on castle-time as stated by Boccio, “In chronotopic terms… the house of Usher encapsulates time and space in a way that is formally constitutive within the tale and much like Bakhtin’s account of castle-time” (61). Delving further into the specifics of castletime in his article Bakhtin states:

The castle is saturated through and through with a time that is historical… The castle is the place where… the traces of centuries and generations are arranged in it in visible form as various parts of its architecture, in furnishings, weapons, the ancestral portrait gallery, the family archives and in the particular human relationships involving dynastic primacy and the transfer of hereditary rights. And finally legends and traditions animate every corner of the castle and its environs through their constant reminders of past events. It is this quality that gives rise to the specific kind of narrative inherent in castles and that is then worked out in Gothic novels. (245)

Temporality, specifically the castle chronotope, is reinforced through the Usher artifacts and

their ties to antiquity and decay. Boccio concludes that “… the castle, as artistic chronotope… stands resolute and starkly opposed to the forward rush of the road” (61). This places road-time as being the dialectic opposite of castle-time, which is further supported by Boccio. Referring to Cindy Weinstein’s theory of temporality in “Time, Tense, and American Literature: When Is Now?” (2023), Boccio establishes that the two types of temporalities form a dialectical nature, “… Weinstein has termed ‘tempo(e)reality’—a tradition of discontinuity in nineteenthcentury literature (a tradition the critic identifies with Poe) whereby sequential, chronological time ‘encounters’ or is embedded within divergent, ‘dialectical’ temporal patterns” (56). Poe implements these “profound temporal experiences” (Boccio, 59) in this dialectical way so they “clash and clamour” (Boccio, 59), something that is crucial to the story and its allegory. These two temporalities exist as opposed and it is through this dialectic dialogue that the reader understands the larger allegorical meaning of the story through the framework of temporality.

Developing this further in relation to alienation, Juhani Pallasmaa in “Inhabiting Time” (2016) states, “… ‘placelessness’ and alienation arising from an ‘existential outsideness’ and we are similarly alienated by the absence of time” (59). The formation of alienation, concerning temporality, can be attributed to the absence of time. In the context of the chronotopes, alienation can then be attributed to the recursive temporality of castle-time or lack of progressing time. Therefore, within The Fall and Poe’s framework, the artifacts and their temporal qualities form another basis for the creation of the allegory of alienation. The Usher house and its artifacts that adhere to castle-time are inescapable through their temporality of "… circularity, of endless repetitions, of return…” (Boccio, 61), while the narrator is the intervening force adhering to road-time that is “…ordered, sequential, knowable, passing away…” (Boccio, 61), possessing the potential to disrupt and oppose it.

Though the two temporal qualities within The Fall “clash and clamour” (Boccio, 59), it is ultimately the road-time chronotope of the narrator that supersedes the castle-time. At the story’s conclusion, all the artifacts and their related temporal qualities fall and diminish, leaving only the narrator. With the goal of the allegorical conveyance of alienation in mind, it makes sense that the temporality that nurtures that alienation would thus cease at the story’s close, emphasising the negative consequences of falling victim to a repetitious time loop that leads to said alienation. Again, it is the dialectic relationship between the two chronotopes that allows the reader to understand the allegory of alienation and its negative implications on the individual.

Boccio identifies the importance of decay to The Fall and castle-time saying, “… Poe’s preoccupation with decay as a physical and temporal condition is related to his artistic ambition… The time of the castle as the time of decay disrupts modern progressive time, the order and optimism of the future-oriented Road” (63). Although it is the culmination of all artifacts that express the castle-time chronotope, the principal one in The Fall is the Usher house itself. Beyond the gothic style of the house that roots its identity and temporality within that of the past and unchanging, it is decay and ruin that cement the castle-time chronotope. In the opening of The Fall, the reader is presented with a description that establishes the house as being in ruin and in the process of decay:

Its principal feature seemed to be that of an excessive antiquity. The discolouration of ages had been great. Minute fungi overspread the whole exterior, hanging in a fine tangled web-work from the eaves. Yet all this was apart from any extraordinary dilapidation. No portion of the masonry had fallen; and there appeared to be a wild inconsistency between its still perfect adaptation of parts, and the crumbling condition of the individual stones… Beyond this indication of extensive decay, however, the fabric gave little token of instability. Perhaps the eye of a scrutinizing observer might have discovered a barely perceptible fissure, which, extending from the roof of the building in front, made its way down the wall in a zigzag direction, until it became lost in sullen waters of the tarn. (Poe 39)

Eventually, the conclusion of The Fall sees the complete decay of the house, namely the fissure in the façade:

Suddenly there shot along the path a wild light, and I turned to see whence a gleam so unusual could have issued; for the house and its shadows were alone behind me. The radiance was that of the full, setting, and blood-red moon, which now shone vividly through that once barely discernible fissure, of which I have before spoken as extending from the roof of the building, in zigzag direction, to the base… my brain reeled as I saw the mighty walls rushing asunder… and the deep and dank tarn at my feet closed sullenly and silently over the fragments of the ‘House of Usher’. (Poe 50)

The story opens with the decay of the house, as well as ends in its complete decay. Hence not only is temporality important, but its representation through the ruin and decay of the physical environment.

Some if not all prior mentioned case studies have temporal elements that can be referred to here. The primary ones of note are Oxygen House, Flood House, Judenplatz Memorial, and Course of Empire. Each will be briefly discussed in their relation to temporality to further add to their value as case studies.

Flood House is concerned with seasonal changes and the shifting of tides that in action change the use and occupation of the house. Occupation and use become dependent on temporality.

Oxygen House is intended to change over time. Upon Abrahams’s death, the house undergoes a metamorphosis from house to tomb. This also forms a dialectic dialogue in that life is juxtaposed against death, and through the change of the architecture impact is added.

Judenplatz Memorial is concerned with temporality in perseverance and preservation of memory. The architecture stands in strong contrast to decay and the passing of time through its form, materiality, and solidity.

Course of Empire includes a temporal shift between all five paintings. The series changes from morning to sunset, in addition to the changing of seasons. The primary device to achieve the conveyance of temporality is the implementation of architecture that by the final painting is decayed and in ruin. Decay in this case allows the viewer to understand not only a political or civilizational shift but also the temporal one. There are layers of temporality imbued within the paintings to reinforce the impact of the meaning of the paintings.

The Lost Museum was an exhibition to celebrate John Whipple Potter Jenks, who passed away in 1894, along with his museum The Jenks Museum. The museum contained around 50’000 items and was closed in 1915 with most of the collection being discarded by 1945. The exhibition told three stories on the site of the original museum. Of interest is the third display which appeared like a traditional exhibit. One case contained one hundred of the remaining original Jenks collection. What is interesting is they were ordered by degree of decay rather than type or period as is typical. Lubar describes the exhibit in more depth saying: