Sisyphus Spring ’24

Cover: digital by Jesse Heater

Inside Front Cover: painting by Sam Besmer

Masthead: photograph by Evan Mullins

Inside Front Cover: painting by Sam Besmer

Inside Back Cover: Saint Louis Self-Portrait, by Rudy Reitenbach

2

Points, poetry by Jens Istvan 4 Skeleknight, digital by Leo Hahn 5 Froggy, poetry by Carson Leahy 6 First Friday Mass, poetry by Andrew Moffett 7 Dawn, photograph by Andrew Moffett

watercolor by Sam Besmer 9 Sangria Cricket Ball, prose by Madhavan Anbukumar 11 Rainbows & Wires, photograph by Patrick Zarrick 12 pastel by Steven HlawnCeu 13 Long Holiday, poetry by Carson Leahy 14 Sioux Passage, poetry by JP Wildermuth 15 acrylic by Jack Hulsen 16 Ezekiel, poetry by Sam Herbig 19 photograph by Jack Auer 20 Sky Fishing, poetry by Conner Leahy 21 collagraph plate by August Geldmacher 22 ceramics by Joss Thenhaus, Keegan DeBoard, Colin Drysdale, Juno Janson, Josh Schmidt, Gus Talleur, Connor McCoy 23 8 years old, poetry by Jake Fitzpatrick 24 Flying By, poetry by Andrew Moffett 25 Hereafterthoughts, fiction by River Simpson, SJ 26 My 7th Grade Self, acrylic by Sam Besmer 29 Color Study, acrylic by Matthew Kleinberg 30 Fear of Failure, poetry by Edmund Reske 31 Time to Fight, charcoal by Leo Hahn 32 Crisp Morning, acrylic by Matthew Kleinberg 34 acrylic by Jack Hulsen 35 A Mother’s Love, poetry by Jaden Yarbrough 37 Schoolboy with a harmonica, poetry by Jens Istvan 37 Snake, chalk pastels by Leo Hahn 38 The Grand Escape, prose by Patrick Byrne 41 photograph by Andrew Moffett 42 Shoreline, poetry by Andrew Moffett 43 Seljelandsfoss, photograph by Andrew Moffett 44 Death of the Working Class, poetry by Declan Richards 45 I Wonder What the Mother Did, prose by Frank Corley 46 charcoal drawing by Colin Schuler 47 Memories of Us, poetry by Triston Ivory 48 A Lifetime in a Day, poetry by Edmund Reske 49 photograph by Evan Mullins 50 photograph by Alex Keuss 51 The Flaw in Time’s Manner, poetry by Brendin Keutzer 52 painting by Sam Besmer 53 An Interior Window, poetry by Andrew Moffett 54 Charge, poetry by William Miller 55 in the way, poetry by Jay Carroll 56 Meditation on the Mundane, poetry by Lorenzo Gutting 57 watercolor by Matthew Kleinberg 58 When You Can’t Sleep, poetry by Frank Kovarik 59 collagraph plate by Christian Blonde 60 Sunshine Storks, photograph by Tristan Kujawa 61 The Infant Account, poetry by Jake Fitzpatrick 62 The House, poetry by Henry Eichhorn 63 photograph by Andrew Moffett 64 This Pen (On the Closing of a Chapter), poetry by Tim Browdy

3

8

Points

Jens Istvan

Can you count the change a soul makes On an abacus, a ledger, or a balance book? Or is it more than gives and takes, Old blindness gone for a second look?

If I looked at you and added together All the good things you’d ever done, Would you smile and put the ink on your feather, Or would you tell me you’re greater than the sum?

3

4

digital

Leo Hahn

Skeleknight

Froggy

Carson Leahy

It didn’t know why it understood just that it did

And it was crying

Its eye of such primal ignorance filled with tears

It understood the moment so well that it started crying

For only a few seconds

This animal

This beast

This soulless thing

Seemed as if it had a soul too

As if it had been stabbed by the same twisting dagger we all felt

As if the event were so powerful

So painful

So reality-warping

That even a creature let its soul leak from its eyes

I didn’t cry

I wanted to Tried to Prayed to God in heaven that perhaps he would let me

I just couldn’t

5

First Friday Mass

Andrew Moffett

The light that shines through the rosy stained-glass window above the organ pipes Is the same light that stains the children in blood red below.

The diseased oak boughs that bray and screech from the winds of Delor Street Are those musicians that play for a people whose song is undocumented.

The damp cigarette butts and vomiting garbage cans are always there, But Mom or Dad or Mom and Dad are never there.

The priest says The Lord be with you to silent spirits. How do you convince someone about Jesus Christ When they have been on the Cross this whole time?

They are the broken shards of a stained-glass window. They are the impoverished branches that have fallen to the dirt. They are the child for the home without a family.

Should they sing if the language be familiar?

Should they pray if the harsh rumble of the police helicopter above Do not disrupt them from their Maker?

Perhaps they pray a different prayer, perhaps they sing a different song. Theirs is a litany of survival, an offering of humblest hope:

That one day, the stained glass may not discriminate with its shades and shafts of light. That one day, they will be the rose petals and not the bloody thorns. That one day, they will nestle in the pew between Mom and Dad.

These children have a dream And for now, That will have to do.

6

7

Andrew Moffett

photograph, Montserrat Dawn

8

Sam Besmer watercolor

The Sangria Cricket Ball

Madhavan Anbukumar

Summertime. It was the time where I biked along with the neighborhood kids in a small village in eastern Tamil Nadu, on the one paved road, stopping at times to go into a friend’s house for a thamalar of water from the huge red clay pots that women in the village kept or a snack of crispy pakora, made from last night’s leftovers. It was the time for climbing the tamarind trees so that we could grab the curved maroon fruit for our stew like sambhar. The time where all the neighborhood kids would come together in the evening and play in the depression left behind by the dried-up lake, running barefoot in the cool terracotta sand. It was the time where my Ayya would dote on my siblings and me, feeding us dairy-filled sweets from the milk of her cows. Summertime.

One summer, in the younger years of my life, I was walking home from my Periyamma’s house during the summer, just past the old red brick house where all the feral dogs used to sleep during the day, when I found a faded sangria cricket ball. It was normal size, about the size of a tennis ball, pretty good except for a small crack along the seam. It was covered in dust, probably from being used so often by neighborhood kids. It looked a lot like me at the moment, dull and done with my day. I picked it up and decided I would play with it later, so I continued walking down the paved road. At the end of the road was a barren offshoot path filled with sand that led to my Ayya’s house. Her house was surrounded by yellow walls and a rusty metal gate in front. Seeing that gate, I reached my right hand to unlatch it, when I heard the raucous cries of the village kids.

As I turned, I heard a voice from behind me call “Allipava!” in the fashion of the South Tamil dialect, leaving off the last syllable of the word, “Is your Thatha home right now, ’cause I don’t want to get yelled at.” Only one person could have yelled that at me; only one person knew my family well enough. I twisted my small body to see my friend Katal. He was like one of the feral dogs that used to follow me around for food: once you fed him an ounce of trust, he followed you forever. He was the son of the only tractor driver in the village. During the twoweek period of harvesting the rice we had free rides in his dad’s red tractor. Katal once drove the tractor by himself, making him the most sought-after friend of the village kids group after me. He and I lived on the same side of the huge lake where everyone lived.

With his “American” T-shirt, Katal usually wore his tattered black corduroy shorts that went just past his knee. He was wearing a faded brown T-shirt with a picture of the Kentucky Derby on the front, which he had probably gotten from my dad. Behind him were Boomi and Nerrupu, both calling out greetings of “yippidi irke,” the Tamil equivalent of “how are you?” Nerrupu was always messing around with the boys, rebelling against the norms of what a girl should act like in India. She would join in all the wrestling and kabaddi we played in the dried up lake. And would generally win in any contest we played, to our dismay. She, like Katal, lived on my side of the lake.

Boomi, the other kid who approached Katal and me, was the son of the village beggar, who would always go around the village after

9

most people had lunch and ask for extra food. His mom wasn’t married but kept herself busy with her five children, the oldest of whom was Boomi. Boomi was the prodigy of his family and of Kirathur, having skipped two grades and still being the smartest in his class. Boomi lived on the other side of the lake, away from Nerrupu, Katal and I. Boomi, which literally meant “of the earth” lived up to his name because of his failure to bathe on a normal basis. Though he was always covered in dust and always wore tattered clothes, my parents seemed to compare him to me, always making him out to be a better person than me.

“Do ya wanna play Allipava?” Boomi asked as he ran his bony fingers through his matted black hair. Nerrupu had brought a cricket bat, fashioned from a kucci off a palm tree.

“Sure,” I said, tossing the cricket ball to Katal. “I have a ball fer us to use already!”

“Where’d ya get that ball, Allipava?” asked Katal, his face bewildered.

“Oh,” I said, lying to his innocent face, “I found it in my house. It was probably my dad’s or something.”

“I was just askin’ cause I lost mine earlier today on my way to school. It had a small crack on the side of it.”

“If you’re askin’ if you guys can have it, that’s a straight-up no.” My stomach turned as I prodded him with an imaginary cattle-prod. “Let’s just go play.”

We all went into the courtyard, a dozen or so more kids following after the four of us. We set up the picks for our game and drew the batting box in the sand with our feet, then we started playing.

It was an everyday thing, playing cricket with the village kids. Ayya would come out of the house to watch us play, feeding us with fried gelebi or pakora. She would cheer on both teams as if we were all her grandchildren.

Boomi and I were on one team and Nerrupu and Katal were on the other. On that particular day I was up at bat, sweat running down

my sun-darkened face staring into the bowler’s eyes. Boomi had scored most of the points for our team, whereas I had scored none. My face flushed with red under the glaring sun, feet warm in the soothing sand. The bowler launched the ball in my direction as I swung the bat with the force used to puncture the tire of a tractor.

I missed it.

Of course I did. Color rushed out of my face as quickly as it had arrived. My face burned, liquid forming in my eyes. I heard laughter all around me, starting out with a few giggles, then some chuckles to full-out belly guffawing. I stared down Boomi, who was looking at me in disbelief, hoping to wipe his smile off his dusty face.

“Allipava! Why’d ya miss?” Boomi asked, running his hand through his hair. “You’re the best on our team!”

I just looked at him and went over to Ayya who at that moment was leaning against the courtyard wall, shaking her head in disappointment. “Ayya,” I said, as I walked over to her, “I’m going to go inside for a thamalar of theni.”

“Allipava, don’t ditch them.”

“I won’t.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah.”

Of course I ditched.

I went back to the searing paved road, leaving behind the soothing sands, holding the sangria ball in my hand. I walked over to the other side of the lake, where Boomi lived. The smell of pakoras frying and the sound of kids playing didn’t seem to surround me anymore. Instead I smelt cigarettes and marijuana burning and old men coughing up a red tobacco phlegm on the ground. Five teenagers stood near small huts, whispering and looking behind me. I turned around. No one was behind me, meaning they were saying something about me.

One of them, the one in plaid and a red khali strutted up to me. “What d’ya want, palam?” Palam was an insult generally reserved for heavier kids.

“Nothing!” I said, not looking for trouble.

10

He looked behind me again, but no one was there. “You searchin’ for trouble then, huh?”

My mind filled with horrible ideas, breaking Nerrupu’s bat, tearing up Katal’s T-shirt, puncturing his dad’s tractor tires, but one thing was held above all in my mind.

The revenge on Boomi. Get him out of the way, and maybe I would score more runs, not disappoint Ayya. Maybe I would be the envy of every parent. Just maybe.

The teenager looked behind me for a third time, but this time Boomi, Katal and Nerrupu were behind me.

“ALLIPAVAR,” they yelled, using the full capacity of their lungs, “WHERE ARE YOU?”

Normally I would be overjoyed to hear their voices, but all I wanted now was vengeance. I turned my sweat-drenched back and darted, leaving behind Boomi and the others on the other side of the lake.

I can only imagine that the teen nodded and smiled at his friends as my friends approached them. I started walking home, as soon as I was in the clear, my back turned to Boomi, Nerrupu, and Katal, tossing the cracked sangria ball up into the air and catching it.

11

photograph, near Telluride, CO RainbowS & wiReS

Patrick Zarrick

12

Steven HlawnCeu pastel

Long Holiday

Carson Leahy

An anxious pine sits there. A parasite clinging to us, set on self-preservation. It knows what it holds.

It has sat there from December now into March. “Wait one more week.” “It’s got good memories.” “It’s got her photo, after all.”

I went downstairs one night to see it. Its eerie glow, the ornaments, your joyful eyes— I felt almost disgusted.

You would be the first one to say Seasons change, we need to move on. You would have made us take it down.

That tree of such distorted reverence. It knows we can’t lay a finger on it. It laughs at our genuine humanity.

13

Sioux Passage

JP Wildermuth

Why are we here, here of all places?

Why are we doing this, of all things?

Again and again, we must run up and down

One hill, then the next, through thick grass and town.

Both up earthen slopes and down tar roads,

Each surface equally destructive,

Where heat burns the skin, my hunger runs thin.

Terror takes stage as we consider our task.

To race the hundred-foot hill seems without point or will.

Lucid pangs ripple an empty belly,

Leaving thoughts tongue-tied and stilled.

Doubt starts to rise, questions seep in slow,

Without words to fulfill, only desperation for a downhill.

This insane journey is unbeaten; to me, it is treason.

Out of all our discerning, we are here for some reason.

I look up in awe. Surely it’s fake.

Can’t shake what I saw;

For it can’t be so mean: it must be a dream.

The hill, the mountain, no water fountains. My mouth, like glue, dehydration, not new, And the dryness ensues.

The pain is too real, like too many missed meals.

My brain cannot feel the sting like steel.

In all parts of the body: legs, arms, neck, it’s unreal.

As we steadily climb, My limbs complain and whine. They say I can’t take it.

But climb after climb, step after step, Though morale so low, hope still shows.

14

Time agonizingly slow.

Legs heavy as molten lead, it gets to my head: So much temptation.

I can give up now, no one will know.

If I “trip” on that log, no further must I go. Not till tomorrow, when I go incognito…

But no.

My mind cannot win; I am not my emotion. The incline, so steep, shall not make me weak.

I do not know

Why I will not give in, But no matter the pain, I will be strong within.

I will be free from my brain; Although it’s insane, It is my time now.

Just as we train.

It is time to begin.

15

Hulsen

Jack

acrylic

Ezekiel

Sam Herbig

“In any man who dies there dies with him, his first snow and kiss and fight. Not people die but worlds die in them.”

—Yevgeny Yevtushenko

“The hand of the LORD was upon me, and he brought me out by the Spirit of the LORD, and set me down in the midst of the valley; it was full of bones. And he led me round among them; and behold, there were very many upon the valley; and lo, they were very dry. And he said to me, ‘Son of man, can these bones live?’ And I answered, ‘O LORD God, thou knowest.’”

—Ezekiel 37:1–3

You have heard that it was said, Not people die but worlds die with them: first snow first kiss first fight forgotten in the dusts of time to which we shall return.

Recordings, meanings, remeanings, the Goodest, Beautifulest, Truest, Realest that I know —to me and to me alone— vanish with mine lights out.

You have heard that it was said, Mere neurons hold one’s world together, One relation to Other;

Nail to hammer

Under to over

Rain to weather

Bear to mother

Guitar to father

(Self to something or something or other)

Backyard to glider

Eitman to Sulphur

Main Street to murder

Mixer, disaster

Langford to banner

Call to no answer

Dancer to Wagoner, crepe paper, wallflower

16

44 to forever and ever (and never)

Lafayette Square to her and to her and the kiss that is always undyingly her. Mere neurons together bear all things, believe all things, hope all things, endure all things;

Association area array awaiting retrieve or erase, like magnet to motherboard.

You have heard that it was said, All Things are ever only half known; perceptions; stirrings of electrified meat; Visions seen only through a mirror darkly.

I see not You but my expectation and impression of you, An impression only an impression of another impression, impressed upon what but a bad impression. No thing known but only passed through a maze of atoms held at arm’s length in their fields, not meeting.

Experience as that and only that which is filtered

Stuffed

Interpreted Stuffed

Schematized Stuffed

Compared Stuffed Paired

Stuffed

Rehearsed

Stuffed

Recalled

Stuffed

And only then seen by some blind mind’s eye

Mind and magic and music only a matrix of matter

Blind on blind off switches on offing till all off …

Standing silently stuffed stretched on sticks so as to scare some crow some space south of Sedalia

Stuffed my head, my stuff-self self-stuffed with separated chaff

Filtered thoughts, dream delusions, wants and loves, arts and sciences accounting and amounting all and only atoms.

Adam told to tend the garden; Adam stretched at arm’s length in his field.

17

And who am I that my scarecrow Lord should come to me?

The voice of One crying out in the desert hanged with me, One come down into onto the sticks with me

One like a root, a tender shoot out of dry ground (son of man can these bones live)

Like One afflicted

Emptied

Struck down

Emptied Pierced

Emptied

Crushed

Emptied

Wounded

Emptied

Bled

Emptied

Broken

Emptied

Shared

Emptied

Given

Emptied

Like One from whom people hide their faces (hide your face)

The voice of the One—(do not turn back)—

He opened now His mouth like a lamb led to slaughter—(take off your shoes)— a call for Elijah—(write what you have seen)

Crying out in the wilderness—(hide your face)—a double-edged sword—(hide your

The YHIAmWhoAmpeacebeuponHimthealphaandomegaWhoisandWhowasalltimebelon gstoHimWhoAmthroughandinandwithallthingsNowMadeNewnowWhoAmbecomeDeath tramplingdowndeathbydeathandtothoseinthetombbestowingLifenowhosannatotheSonofd avidnowandalwaysandinsaeculasaeculorumamennowholyholyholyLordGodofarmiesblessed isHewhocomesintheNameoftheLordJesusChristSonofGodhavemercyonmeasinnerholholyh olyholyholyholyholyholynowandalwaysuntotheLambwhoisslainWH turned to me

in the cool of the day:

18

“But I say unto you: All Things have Me as their measure; Piercèd hands hold all-world together. Not people die, but world without end: This day you shall be with Me in paradise forever.”

Amen.

19

Jack Auer

photograph

Sky Fishing

Conner Leahy

Paint chips off my board

Clouds and sun and sound tail me

I cannot be caught

Faster wind hurls me

Like a zephyr I surf sky Years and lives pull me

Pulled by the gravity of winter, Left to sink into warmth, Enduring still, how can you still wait?

Attend yourself for me, Sleep, not for the shelter of dream, Endure from the peace of your heart.

Your feet under sheets

My feet running on the clouds

My pulse thrusts forward

You binoculars

Watch me soar high and far now From your lonely bed

Limp string in my hand,

I hold your cold finger with my clasping hands, You held my small hand on your soft finger, you taught me to fly, now teach me to walk, but I, the kite you hold onto, I am not ready to come down.

20

21

Geldmacher collagraph plate

August

M&Ms: Joss Thenhaus; Sour Patch Kids: Keegan DeBoard

Dots: Colin Drysdale; Heath: Juno Janson; Kit-Kat: Josh Schmidt

Fun Dip: Gus Talleur; Snickers: Connor McCoy ceramics

22

8 years old

Jake Fitzpatrick

wish i could fashion a pillow fortress wish i could scramble up my climbing tree wish i could make my fingers sticky with the sap of peach popsicles wish i could gallivant on my seven-geared razor wish i could trade faded baseball cards wish i could play hide and seek in the park wish i could beg for a kid’s meal wish i could watch star wars for hours on end wish i could build lego kingdoms wish i could have a catch with dad wish i could be a kid just one more time.

23

Flying

By

Andrew Moffett

A fisherman’s sail sighs along, trough to crest to trough again

On the exhalation of the Gulf of Mexico.

Several miles overhead I glimpse the glittering sea, Turbulent to the little boat but placid to my eye.

Motion at that altitude is lost in translation,

And from my double-paned window the bobbing skiff below appears still, Painted into the parched crack of a marbled desert floor.

What is it that I see?

My thoughts jettison just as the fisherman’s rod bends to the racing marlin. To relative realities, each timestamped, each negotiating his time.

While one’s head is down, the other moves, or perhaps unknowingly we move ourselves.

Will the water wave again, or will that pesky airplane finally buzz away?

I am too far gone to see what I once saw, but then again, That fisherman was too far to see at all.

I think I need a second opinion.

24

Hereafterthoughts

River Simpson, SJ

Ileft my laundry in the washer—the thought struck me just after the truck did. As last thoughts went, it was pretty uninspiring. No flashbacks to the most important moments in my life, nor remembrances of my greatest regrets, nor any dashed hopes of my bright, or maybe not bright, future crossed my mind—just the insignificant observation that, given my untimely demise, my clothes would grow mildewy.

I can’t say that I led a morally good life or that I believed in karma, but either way, being hit by a truck felt a bit much for how I thought things were going. Granted, I did see it turn the corner, and I could’ve waited for it to pass, but I assumed it would see me and stop like every other vehicle’s done for me in the past … a naive assumption to make, I know, or at least now I do. Looking down at my body—I’m not sure from where exactly— I felt assured that I, or I should say my family, would win the ensuing court battle, but between bone and steel, I lost terribly.

The day started out as normally as any other day. No one wakes up thinking this will be his last day. I woke up, took a piss in the shower—gross, but sometimes you forget, and it all ends up in the same pipe anyways—and then I sniffed the clothes scattered around my perennially ramshackled apartment until I found barely enough matching bits of clothing to be passable in public. The rest I gathered up into a reeking ball of mismatched colors and fabrics and threw it into the wash on the quick cycle. Hoping it all would turn out all right, I watched whites, lights, darks, and towels all swirl together as one agitating mass beneath a disintegrating, blue detergent galaxy. It appears my misplaced optimism may have led me here in more ways than one.

Where exactly here is again, I cannot say for certain. It’s a rather opaque plain of nothingness that spreads out beyond an abyss of pastel yellow that for some reason smells faintly of lilac and eggshells, not particularly harmonious scents but also not particularly pungent in combination either … vaguely reminiscent of a doctor’s glove. If this is supposed to be Heaven, I am vastly underwhelmed, and I’d say God’s missed His mark for paradise. Then again, if this is Hell, I see nothing particularly torturous about it either—unless of course its hollow, wedding cake-like quality is somehow supposed to eat away at me as time goes on in some horrifying way. As they say, time will tell.

Recalling my shuffling toward the kitchen, I then popped a breakfast burrito into the microwave and leered at its Miss Universe pageant twirl for the recommended ninety seconds. Impatient as I was hungry after the buzzing ding, I burnt my fingers unwrapping that supreme beauty as its volcanic sauces dripped down its metallic ball gown and onto my unsuspecting hands. Pained, I ravished it anyway into nothingness and flung its fleeting remnants into the trash can. Undoubtedly, the next Miss Universe would have been just as unfortunate in satiating my hunger. Sadly, it was the last thing I ate; its existence proved futile, deconstructed into millions of nucleic acids my body would never use the morning I metamorphosed into a corpse.

My last girlfriend said I’d make a lovely corpse. Can’t say she was wrong. My mangled manifestation of death did hold a certain charm about it. It was the cheeks, I think. Even in death, they still held a rosy meekness which was the bane of my teenage existence;

25

My

perpetual blush served no one well. A crowd has formed around me, or what was me, or is me in a sense separate from the me looking down on me. I wonder if any of them have noticed my macabre beauty. I can’t hear anything they’re saying, but I can discern gasps, morbid curiosity, even looks like someone’s calling 911. Surprising. Really, I’m getting more attention now than I ever did in life.

I got a text from my buddy Ricco asking me to join him for brunch at ZanziBar, a

swanky nightclub that oddly enough served brunch on Sundays. He wanted me to meet his girlfriend. More than just a recurring hookup, they’ve been going steady for about a month now, and he thought it best to introduce her to his friends. Whether this was his thought or hers, I couldn’t be sure. Regardless, ten-dollar bottomless screwdrivers and runny Eggs Benedict didn’t sound too bad this morning, especially after what had passed for my breakfast. With my stomach growling,

26

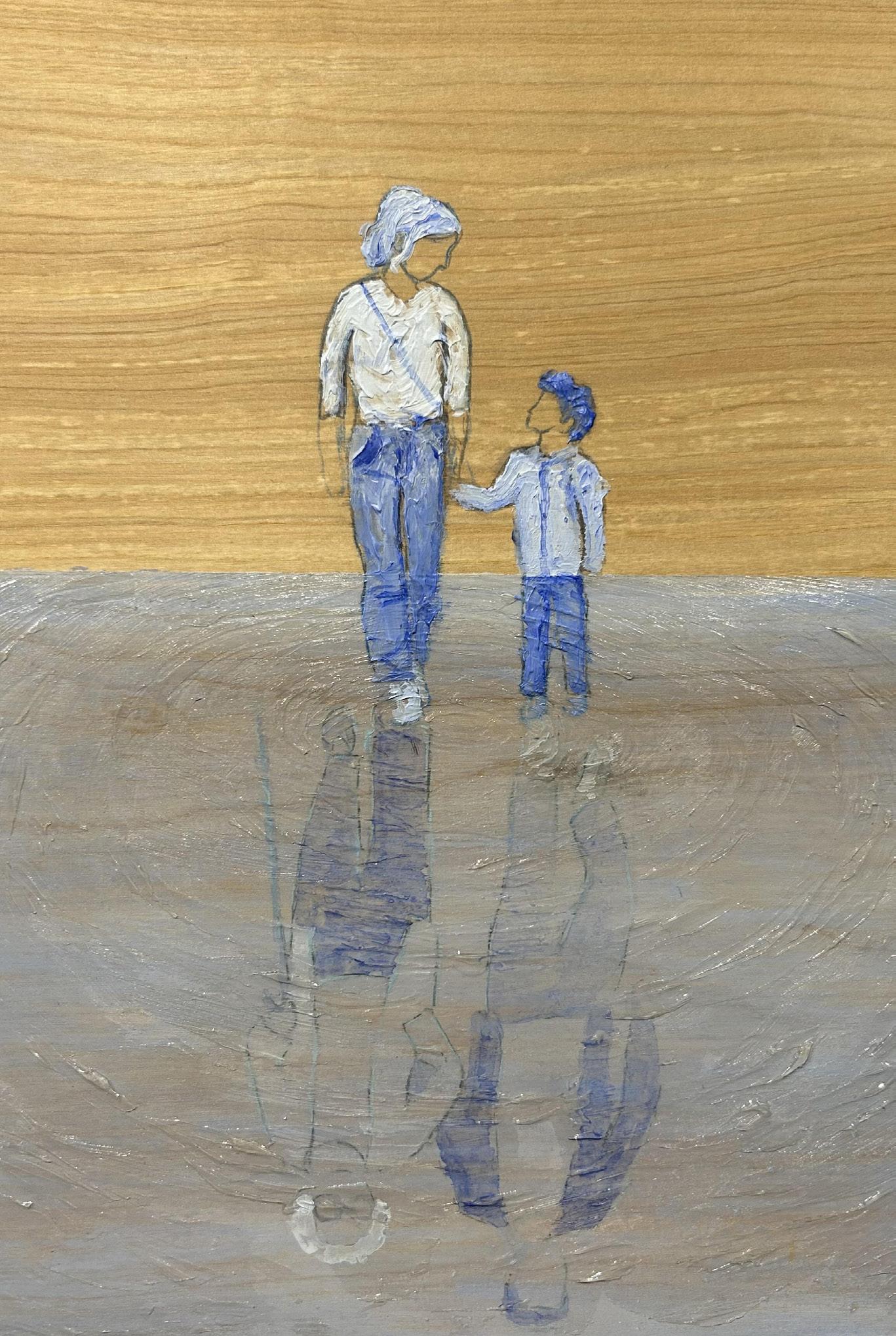

Sam Besmer

acrylic applied onto wood board

7th gRaDe Self

I accepted the invitation and headed out the door.

After locking up the joint, I heard through my apartment’s paper-thin walls the blare of my washer signaling it had finished its job. I’d just get it later, I thought, and strolled on into town not wanting to arrive late. Besides, Mrs. Donahue upstairs hated any ruckus, and I enjoyed agitating her from time to time. I wondered how she’d react to my death. Sure, we didn’t exactly get along, but I walked her deaf, senile Pomeranian from time to time, and she’d occasionally bake me cookies. Oatmeal cookies … but a cookie’s a cookie. In the end, I’d imagine her giving a slight frown and then moving on with her life just like I did after my mother died.

That may sound heartless, but what else is there to do in life but move on? I certainly loved my mother, but the passersby were already passing by my body without so much as a second glance. We’re here only for a short while, and then we enter this vacant place fabricated out of baby room paint swatches. I guess I’ll never have a family of my own. Can’t say for sure that I definitely wanted one, but now that it’s out of the question completely, I sort of wish I’d taken all that cultural claptrap of settling down and starting a family a little bit more seriously. At least then I would’ve had someone to mourn and remember me beyond what will be the incredibly short obituary in the local paper and the even tragically shorter memory of these random bystanders.

The sun’s rays hammered me as I strolled to meet my friend and his “cool, chill” girlfriend. He sent an emoji-laden Snapchat of them waiting together for me at the bar. I knew Ricco had rizz, but she was way out of his league. I glanced down then and found I was sweating buckets beneath my cottonpolyester blend v-neck; its chic mauve distastefully blurring into a disroyal purple. At least they wouldn’t notice the pit stains because they’d be hidden in a gossamer pool of

sweat—the lesser of two evils? Contributing to this heated hell, the path taking me to ZanziBar meandered through the glassiest parts of town, so the reflective glare piercing my eyes nearly blinded me the whole way. This reinforced my hopeful decision to cross that fateful street. Just on the other side of the asphalt sea blistering in the sun was the glorious shade of poplar trees dotting the way to my destination. Comfort is a secret killer.

The crowd that still lingers about me begins to disperse. Initially, I think, out of pure, unadulterated boredom. In actuality, an ambulance had just arrived wailing its peculiar cacophony, and they were making room. That rando must have really called 911 after all. Now, I can’t exactly feel the touch of the paramedic as she graces my neck with her latexed fingers, but I enjoy the horse-like bobbing of her ponytail as she flounces to my side. She seems to have sensed something promising in my limp corporeal remains because she motions for her partner to grab something from the ambulance that still whirls like the Fourth of July.

I never liked the Fourth of July: the banging, the buzzing, the perpetual craning of the neck to witness fleeting bursts of magnificence fade into obscurity. It filled me with dread and gave me a terrific headache. Amidst my musings, the paramedic with eyes radiating care starts performing CPR on me. My chest bobs up and down much like her ponytail, but I feel nothing, not even the touch of her lips through the thin sheet of plastic saving her from whatever microorganisms linger about my mouth. I find her rapt attention extremely touching—if a tad violating. I can’t recall the last time someone stared at me with such devotion. A solitary tear proceeds to roll down my cheek … not my real cheek—my metaphysical one or whatever it is. I wouldn’t have guessed it could do that. This surprise swats the stray reflection away like an unwelcome fly, and I begin to wonder what other

27

things I can do in this state as the erstwhile scene continues to unfold before me.

As quickly as he had vanished into the ambulance, the fellow paramedic reappears in a haze of blue and white standard-issue uniform while carrying a defibrillator. They really are going to try to bring me back to life—just a diligent pair of postmodern messiahs trying to subvert death with the power of God harnessed inside a tin can. This I have to see. Settling in now for a show, I try imagining popcorn—but no such luck. While I could cry, this place doesn’t function purely on imagination or sentiment. I watch popcorn-less but transfixed as she stops chest compressions and he slices off my sweat-laden V-neck with a pair of medical shears. My pale torso shimmers spectrally in the summer sun reflecting its glare just as much as the windows had done. I feel bad for the paramedics, unquestionably blinded by my lighthouse of a chest.

More morbid pedestrians gather for the newest street performance of Young Frankenstein as the AED, the miraculous invention of the Good Doctor and Igor, charges to send an electric shock through my body. Undoubtedly, this production would receive critical acclaim. Indeed, how could it not with my flesh about to wriggle on the crosswalk? The image suddenly conjured memories of Mr. Hendrickson from 2nd grade. I was a caterpillar in some pathetic, stock-school play he was directing. I had one line: “I don’t like potatoes,” and I wouldn’t go on. He was livid, on the verge of convulsing, but I refused to go on stage dressed as what could best be described as a moldy tomato. One of the more precocious and pretentious second graders, Molly Simons, dressed up as a bee, delivered my line instead. As the crowd awed at her pittance performance, I felt a tinge of envy and ran away crying. My mother found me curled up in a cubby.

Zap. After the first bolt of electricity, I

feel … I feel pain, excruciating pain all over my body. Like I had been hit by a truck…, well, at least that makes sense. Quickly, it fades though as the paramedic with the gorgeous, bouncy ponytail continues giving me CPR. I zero in on the fine brunette strands of her hair that fly every which way as she rhythmically presses up and down on my chest. On a different day on a different occasion I might have asked for her number, but seeing as how we’ve already technically reached second base, it’d probably be too awkward to start afresh. C’est la vie, or more aptly put, c’est la mort

Zap again. The second bolt courses through my torso. The pain stays longer now, and I even begin to feel the temporary weak beat of my heart. It pumps twice then ceases. This minor palpitation does not go unnoticed by my saving angel. She rejoins her efforts now as the crowd stares on; no game of life and death at the colosseum was ever so thrilling as the one now playing before me, perhaps because I am intimately involved and the notion that I could come back from this antechamber to Easter intrigues me. She proceeds unaware of my dire interest in her work.

Zap once more. With the third bolt, my lilac and eggshell-scented world fractures into cracked pastels falling away in some Jackson Pollock nightmare turned dream. I close my eyes. I breathe. Gasping. Wishing almost to be dead again. My body’s broken, mangled, but I live on despite myself. The odious smell of sweat mingled with car exhaust stirs my clenched eyelids to open upon the woman with the seraphic ponytail bristling with God’s glory. She smiles, amazed if not stunned at her handiwork, as the bright sun blinds me yet again. I blink incoherently.

“Sir, please lie still. You’ve had an accident,” she says, touching my shoulder reassuringly.

I respond with the first thought that pops into my mind: “I left my laundry in the washer.”

28

29

Matthew Kleinberg

acrylic on panel

ColoR StuDy

Fear of Failure

Edmund Reske

When you’re climbing up the mountain and you might not reach the top, It’s not the tired legs or burning chest that make you want to stop. While you try to win the battle, you’re not thinking of the pain;

It’s not the bruises, cuts, and wounds that make the spirit wane.

It’s the worry that gets you, it’s the what-if’s that kill.

Yes, it’s the fear of failure and the doubt that break your will.

Why can’t you look for sunlight when you fear you might be caught In the darkened spider’s web of a trial yet unfought?

Why can’t you stop to realize this struggle will not last, Instead of hoping only that your spirit can hold fast?

It’s the worry that gets you, it’s the what-if’s that kill.

Yes, it’s the fear of failure and the doubt that break your will.

A stone of apprehension in the mountains of the mind

Can start an avalanche of worry that will turn your reason blind.

So can you keep your panic caged when your back aches from the load

And your weary head bows downward as you march along the road?

It’s the worry that gets you, it’s the what-if’s that kill. Yes, it’s the fear of failure and the doubt that break your will.

As you plummet down the endless pit that gets darker as you sink, You think back to the moment when you teetered on the brink. You could have stepped back from the edge and saved yourself the fall, But could you really mock the fray and change your mind at all?

It’s the worry that gets you, it’s the what-if’s that kill. Yes, it’s the fear of failure and the doubt that break your will.

Doubt’s constant nagging fights the pain and pulls till all expires. Failure nears, but broken will has relit dying fires.

The fears that oft have chased you push you towards your aim. You could never reach the end without this urging flame.

30

31

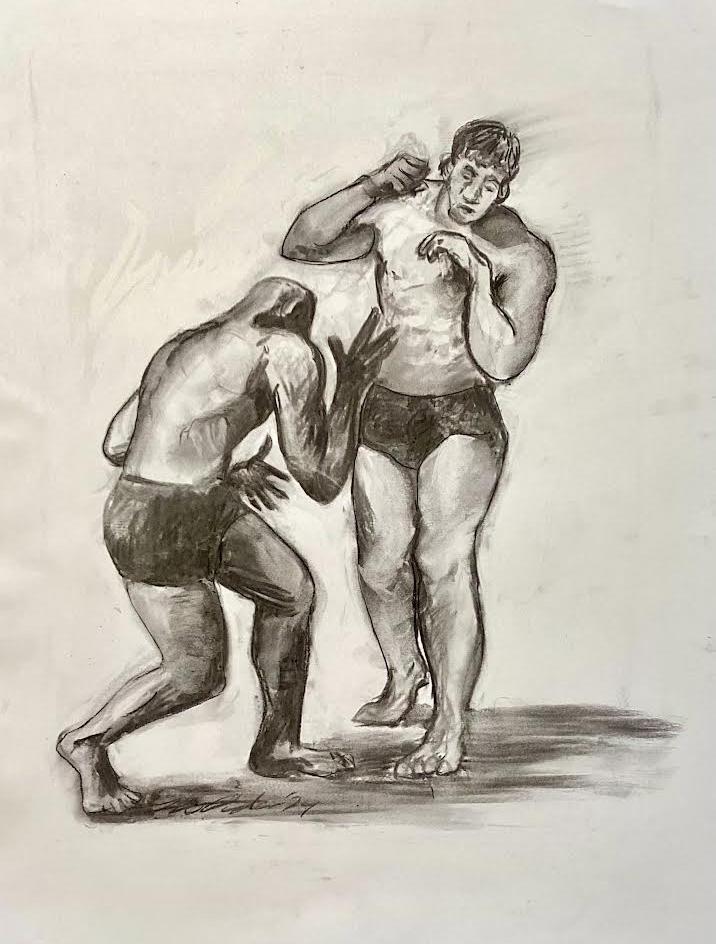

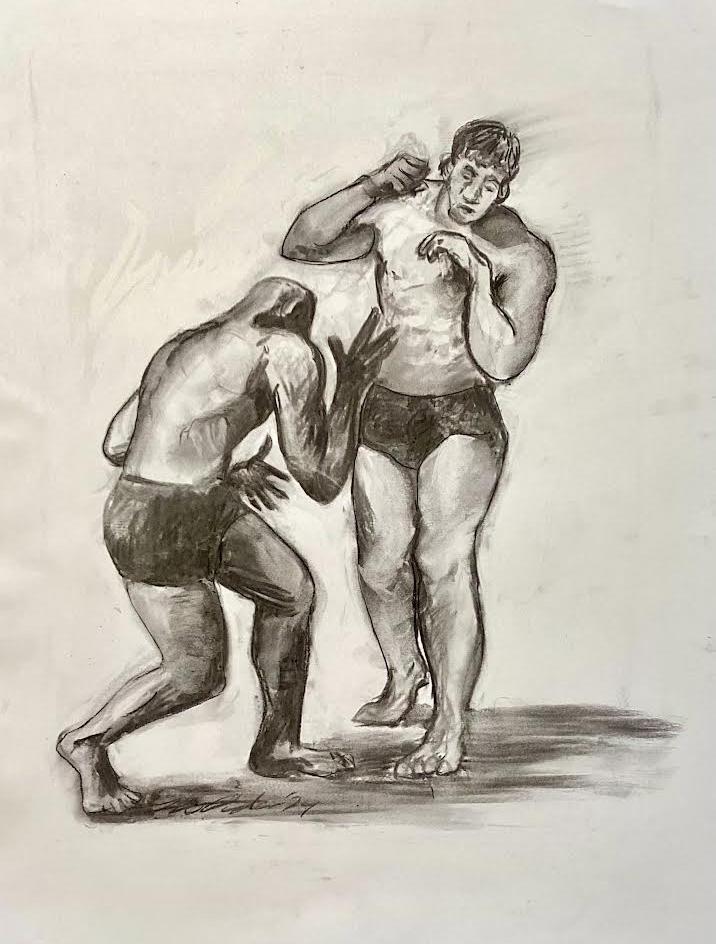

Leo Hahn charcoal

tiMe to fight

32

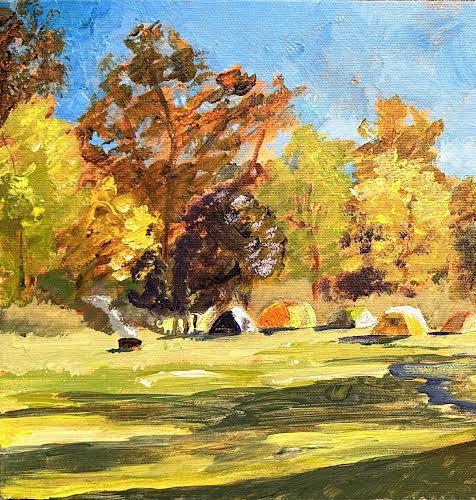

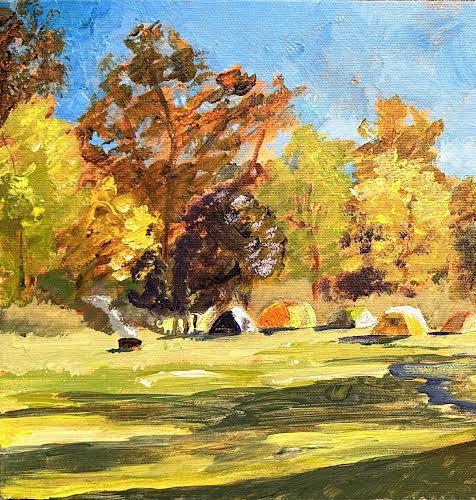

CRiSp MoRning

Matthew Kleinberg

acrylic on panel

34

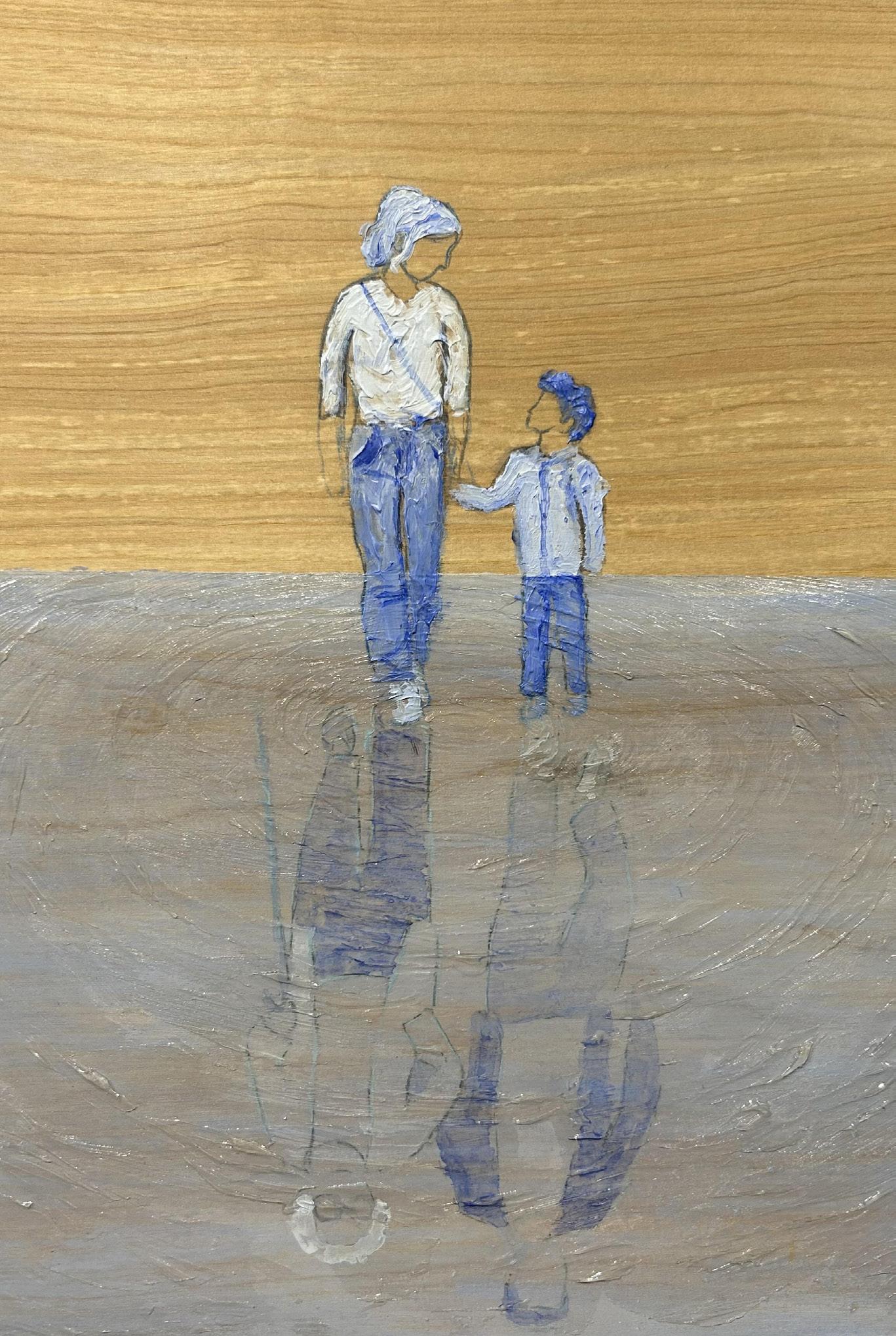

Jack Hulsen

acrylic on wood

A Mother’s Love

Jaden Yarbrough

Bundled up, making my way through town by train, moving as lightning does, all a blur.

I stepped out at the vast two-story station and stumbled upon a mother, resting, almost sinking into the colorless concrete, like quicksand, shivering in the brisk November air soon to transform into the nipping Christmas chill. A time to be alive to live freely without strife.

The child in her arms, birthed no more than a month prior, his tiny gums sucking a bottle that the mother cradled in her hand, tenderly as she nestled his head, no bigger than a mango, lovingly in her arms.

Blanket, ear muffs, and a thick blue coat: That child wouldn’t shiver in her worst nightmare.

In an instant

I made my way to her, hopping across the tracks, and fiddled around for loose change in my coat pocket, whatever I could spare. Up close now, I could see thick and puffy bags under tired eyes, and long, thinning brown hair, flowing freely down the back of her neck. She raised her eyes toward me, still caressing her baby as I extended my hand, and she offered a weak but full smile that stretched her face like a rubber band that had grown stiff by sitting in a drawer for twenty years.

Rising slowly to her feet, gingerly as an old woman would,

35

She shuffled toward the tracks and, tip-toeing across the empty rails, made her way to the other side, where a small convenience store stood. In no more than a minute or two, she came out with a fresh set of gloves, too small for her hands which themselves were glazed with frost like she’d been holding an icicle or snowball in her palm. Nevertheless, she took her babe’s little nubs And while pulling the gloves past his wrists I caught a glimpse of something beautiful: A genuine smile, Unforced, voluntary Her face seemed to glow.

I drifted out of the station soon after but took one last glance before my departure at the mother, her lifeblood nuzzled between her arms. She struggled to fill out her single layer of clothes, her cheeks sunk deeper than her eyes. Yet the baby was plump, perhaps overgrowing the gloves already in just the brief moment I’d been standing there. I got lost in his bright, sapphire-blue pupils. I saw a future; a life of prosperity, of joy, of freedom, A yellow brick road, for him, perhaps. For Mom, the train station sidewalk would have to do.

On that barren concrete, teeming with disease and filth, the future remained mysterious as it had been for years. The child, not yet even that, had so much more to see, yet this was all it had known. Oh, how many more things to see! How much more Mom had planned, too: a trip out west, an escape from monotony, before the depression struck so suddenly so tragically.

But that didn’t matter anymore. She had her heart wrapped in swaddling clothes, had the light of the world sleeping in her arms, and she was happy.

36

Schoolboy with a harmonica

Jens Istvan

I can’t see where the smog and sky begin on this dreary January day.

I look to my right and see, hiding from the cold rain:

A child, a song of war he sings, Maybe eight or nine—too young for such things. Of glory, of passion, the dead and the bold, I said to myself, “Oh world, you’ve grown so damn cold.”

On his walk to school, the boy’s short of breath, A child so young should never think of death

A tale of sorrow the young should not know, But sorrow breeds sorrow, and sadness feeds woe. While the children weep for pain not their own, The world keeps spinning, and never atones.

37

Leo Hahn chalk pastels Snake

The Grand Escape

Patrick Byrne

Every now and then, I wonder about my family’s old stories: the time when romantic embellishment overrides fact and the stories twist into triumphant tales of grandeur. I go all the way back to my greatgreat grandfather, Joseph Leritz—or the Frenchman he was before the Ellis Island customs officer changed his name from LeRitz to Leritz. My grandmother is the only person I know who knew him, but since she was born two months after the stock market crashed and could have been classmates with Anne Frank, it is safe to say that we could not be further apart from each other. Only when my family gathered at her house could I piece together any details about our family history. I sat in my chair at the kids’ table and leaned toward the grownups as they discussed the story.

“He was the first Leritz to come to the United States.”

“The Germans took over his town in Alsace-Lorraine.”

“How long ago was that?”

“I think during the time of the German Empire.”

“That’s incredible! Did he really escape the country like that?”

“I think he paid someone to help him.”

That’s when I recognized the familiar voice of my dad.

“What was he like, Mom?”

My grandma stopped eating for a moment and rested her fork on top of her mashed potatoes. Everyone bent over their plates while she tried to recount something from decades ago.

“He was such a sweet, kind man,” she finally said with a smile. “I would sit on his lap, and he would sit on the porch swing. He

would tell me the story about coming to the United States.”

That’s when my grandma would recount the story in animated detail. But I always wanted to hear the whole thing because it sounded so romantic and thrilling. I finally got the chance at my grandma’s house one day. My siblings were in town from college, so we were all spending the day with her. I remember sitting at the table with my grandma while my siblings talked in the other room. She was showing me many photographs taken almost a hundred years ago—most of them were of her family when she was just a little girl.

“And this one is of your great-great parents,” she said. “Joseph and Elizabeth Leritz.”

I looked down at the photo. Seeing someone I had heard such heroic tales about as an old man was bizarre. In the fading yellow photograph, he stood tall with broad shoulders that stretched against his cheap white shirt. Long, narrow suspenders wrapped around his shirt and connected it to his charcoal pants. But his clothing didn’t really capture the kind of man I had imagined him to be. His face was worn, clearly showing markings of age, but he still had a broad smile painted across it. His hair looked thin but still dark, as when he was younger, with its sides stretching just above his ears. His ears were probably his most noticeable feature; they were large and wide, like those of an elephant. I can only imagine the teasing he endured from my grandmother when she was little. While looking at the photograph, I got the impression that he was the kind of man who had lived a hundred lives but was finally at peace.

38

“Hey, Granny,” I began.

“Yeah, Patty?” she asked.

“Could you tell me the story of how he fled Germany?”

She laughed. “Of course I can!”

Joseph lay on top of the hill in the dry grass; it pricked against the tip of his chin as he stared intently across the field. Just across the field, at least thirty guards walked across the border. There was no actual border, no fence or line drawn to differentiate one side from the other. Joseph knew this, though; the Germans had just invaded this province of France and hadn’t had the time to erect barriers. Joseph glared intensely at the soldiers while he grabbed fistfuls of grass. The late-spring humidity soaked his back in sweat. It was often like that in Alsace-Lorraine.

“There it is,” Johan said. “Like I said, it’s ten thousand marks.”

Joseph shrugged and pulled out the crumbled money from his pocket.

“No business even accepts marks around here yet.”

Johan just laughed in his gravelly-low German accent. “They soon will,” he replied. “Das ist schließlich das Vaterland!”

Joseph smirked. “And that’s exactly why I’m leaving.”

The two waited there so long that Joseph’s hands were lime green from the grass. He saw an opening in between some soldiers and nearly shot off the ground like a rifle, but Johan yanked his collar back.

“Not yet,” he said. “We need to wait.”

Joseph felt his heart beating against his ribs, but he wasn’t nervous: he was furious. Ever since they marched in, he had felt that way about them. He remembered sitting on the porch with Elizabeth while she taught German cases and he taught her French prepositions. They both sipped lemonade and took notes on torn pieces of paper. It was then

that they heard the thundering drums and the trumpets. It was like a parade no one wanted to see. When they saw the soldiers, Elizabeth gripped his hand tightly and wouldn’t let go.

When he started thinking about her, he couldn’t stop; he scrolled through a collage of random memories. They had seen each other every day, and now he wasn’t sure when or if he’d see her again.

“Go.”

That was all she said to him when he told her his plan just hours earlier. That’s when Joseph hit himself in the head to get himself to stop thinking about her. He didn’t think it would do him any good now. Just past the dense forest the guards patrolled, Joseph heard the faintest whisper of thunder. After a few minutes, the hill was drenched in rainfall.

“Das Bingo,” said Johan.

“It’s just bingo,” replied Joseph, grinning.

“In a couple of minutes, I’m going to tell you to go,” explained Johan.

“I’ll go anytime,” replied Joseph.

“Yeah,” said Johan, slightly annoyed. “That’s exactly what gets kids killed in situations like this.”

Joseph barely heard what he said; he was gritting his teeth in anticipation. The rain was like bullets against their backs, and the mud filled his cheap straw shoes. He laughed when he realized how silly it was that he had worn a white shirt for tonight.

Johan gripped his hair and shook his head violently.

“Hallo! Are you listening to me?”

That caused Joseph to snap out of his thoughts again.

“It’s almost time,” said Johan.

Joseph nodded. “Give me a countdown,” he replied. “And be sure to count in French. I need to focus.”

Joseph crept off the ground and slowly shuffled down the side of the hill. He stretched his leg back and angled his back almost horizontally to the ground. His eyes were misty

39

from the rain and sweat, but they still burned into the backs of those soldiers.

“Dix.”

It was then that he started to think about everything in his life that had led up to this moment.

“Nueve.”

This was his story, and here was where it would begin.

“Huit.”

Years from now, he and Elizabeth would tell this story to their children.

“Six.”

The story of how he stood up against the German soldiers.

“Quatre.”

And how he escaped their cruel oppression.

“Deux.”

His own grand escape.

“Une!”

As Joseph shot off the hillside, only one thought was in his mind.

Au revoir!

Once he landed at the base, he slipped on the mud and fell on his stomach. He scrambled to get back on his feet, now covered in mud, and continued sprinting through the pouring rain. The frequent thunder masked his footsteps for quite a while, but he kept having to slow down to get his feet out of the mud. The closer he got to the guards, the more frantically he ran. He was so close that he could see the freckles on one of their cheeks. Their guns also looked much bigger closer up. He ran past them even though his breath was tight, and he felt his lungs being tightly squeezed. Once he was past the line of guards, he wondered if he was safe, but then he heard the soldiers’ voices only a few meters behind him. A gunshot flew past his ear. His ears sounded like a banging pot and throbbed like his heartbeat, but he could hear the soldiers shouting behind him.

“Töte sie!”

Joseph wished he didn’t know German when he heard them screaming. There was gunfire all around him, and he thought each shot would be the one that hit him. He jerked his body back and forth and tried to run in a zigzag to make it harder. As he ran, he could barely think. At that moment he felt only fear. The most horrific fear he had ever felt. The Germans twisted into frightening demons; the gunfire was like their screams as they chased him. As he ran, he saw himself die hundreds of times in hundreds of ways. At some points, he couldn’t tell if he was still alive or if he just hadn’t feel the bullet yet. He ran like this for what felt like days. Whenever he thought he had made it far enough, he would hear the screaming drawing closer. It was the purest form of hell he had ever experienced. His muscles and bones shook from exhaustion, and his body bled from running through thick bushes and greenery. Finally, the sound of the screaming subsided, and all that was left was the beating of the rain. He limped into a wide clearing of the forest and collapsed against the stump of a fallen tree. He threw his limp body on it and looked down at his hands. They were brittle and felt as if he could snap them off. His ears still rang from the bullets, and he kept hearing them over and over. It didn’t even register in his brain that he was now in France, his homeland. He lay on that stump covered in mud and blood, his entire body shaking like a beaten dog. At that moment, he thought back on all the joys of his village: his parents, Elizabeth. They all seemed so distant now, as if he had experienced them a lifetime ago. There was no celebration for his escape, and as he thought more and more about his old life, he couldn’t help but weep.

So he actually cried?” I asked my grandma. My grandma smiled gently. “Like the day he was born.”

I sat back in the creaking chair and couldn’t wrap my head around it.

40

“

“He didn’t like to tell that part of the story,” she said. “I always liked that part.”

I sat up, a little shocked.

“Why would you say that?” I asked her.

She smiled. “Because it makes the story more human.”

She stood up and put the photos away. “We should go get something to eat.”

I still didn’t get out of my chair. I couldn’t stop thinking about how the hero of my family’s history cried alone in a rainy French forest.

41

Andrew Moffett photograph

Shoreline

Andrew Moffett

42

Chaos constrained to the random recurrence Of ebbing and flowing, birth and death On the smooth grit of trod-on beach.

Whispering recesses and silent tempests Sound from the black horizon offshore.

The water sifts, or perhaps it is the sieve; Up and down mean nothing to colliding realities.

There is something beyond twilight

Where the pulse of the sea is law.

Where one’s compass sleeps in Dialogue between currents and foam.

Where salty spray tugs timid time into An ocean we’ve labeled eternity.

We see by the sound of the waves

Tackling and tickling the shoreline.

But can we hear the water whispering?

Our minds heave with fears of what we cannot see.

Unseen motion propagates an unforgiving notion That our gentle ocean shore is a barren desert.

Our calls for help drown the intimate cry of the sea, And we whittle our dark nights dry.

And yet you are going to get wet. The sand slips beneath the waves, Swallowed by a singular surge of surf. Salt of the Earth and Sea were always the same Seasoning of a friend you knew before you knew the ocean. The black is not a barrier but an invitation To trust in that soft gentle sound.

Pitch and roll and churn all you want, but it levels out to this:

You were called to the water.

43

Andrew Moffett photograph

SeljelanDSfoSS

Death of the Working Class

Declan Richards

It is I who ring the wretched clock of time

It is I whose hands do toil in the dirt

It is I who labor and who know no end

And it is I who get forgotten.

From politics to ethics and beyond I am left in my rotting shed

Trying to remember when they cared About us, the laborers, the plumbers, the men.

And when I am dead lying on stone

Who will recall my life of struggle? None, for they will all be lost, In lies and happy endings’ marvels.

But I will know no end and no joy

For it is I who bear the curse of Adam

Oh it is I who am forsaken

The working man is lost always.

44

I Wonder What the Mother Did

Frank Corley

Iwonder what the mother did while the prodigal child was squandering the inheritance on debauchery. On wine, waste, and all manner of wickedness. Did she take to her bed, worried sick about her youngest child? Was she unable to function, burdened and worn down? Did she give up living if she could not take care of this one who sprang from her? Or did she work the fields, taking charge of the farm while her husband worried over the return? “Let it go, dear. We have crops to tend, other responsibilities. People depend on us.” Did she take turns watching with her husband, going to a high hill on their land every other day, searching the horizon for some sign of the return of their lost child? We are not told. We do not know. We know only how she stared out the window, eyes moist, kneading the bread, punching down the dough, forming the loaf because her children were beyond her reach. Working and fretting, brooding, troubled by concern for her husband. When her child was returned to her, she must’ve relaxed, knowing all were safe again. She stopped through the kitchen to check on the meal. “Ate nothing but pig slop for months! Let’s make sure

everything is just right.” Then out to the fields, where the steady older child worked, unaware. She watched for a bit, from a distance, then went to her room. She napped that afternoon, dreamlessly letting go. Finally, finally able to relax, but knowing more was coming. That first evening, the older child came into her room after work, sat on her bed, next to her as she read. “He killed the fatted calf, threw a huge celebration. I didn’t even eat.” She lay down her book and pulled her firstborn to her chest. She quietly pulled her fingers through sweaty hair. “You must be tired. You’ve worked hard today. Thank you for that. I’m proud of you.” As she closed her eyes, just then, a tentative knock at the door. “Come in. Please.” They both knew who it would be. Who crossed the room to the bed. Silently, meekly even, sat on the floor. “There’s room. Don’t sit on the floor.” She offered her hand. She put her arm out. “You must be worn out. It takes a lot to admit you’re wrong, to come back. I’m proud of you.” She kissed the top of each head. “I love you both.” She spoke stating fact, leaving no room for doubt. “Nothing you could ever do will change that.”

45

46

charcoal drawing

Colin Schuler

Memories of Us

Triston Ivory

Where I come from we played any game you could think of, with any ball of any condition we could find. As long as there were no holes or nails, it was used

Where I come from we played until the streetlight came on, and moms and grandmas would come outside yelling, probably for the second time that day since we couldn’t be running in and out the house letting all the “good air” get out, so instead we’d drink from the garden hose when the sun got a little too hot

Where I come from we would fight after arguments then move on like nothing happened because the kids on the other block wanted smoke; over what exactly I have no clue but you can’t leave the guys by themselves

Where I come from we would take advantage of the abandoned houses next to us or in the alley to work on our brick throwing, all the while not knowing how those houses led to us being friends by circumstance

Where I come from we’d end the day on one of our porches talking about who would beat who in Madden or 2k, what team was gonna win the NBA Finals or the Super Bowl, and freestyling to whatever type beat we could find on YouTube saying things twelve-year-olds shouldn’t be saying. Then we’d get in trouble because we were out too late

Where I come from we wouldn’t realize that those times of playing together and hanging would go away so soon. The more we lost our innocence, the further we grew apart, those moments turning into distant memories and only head nods in passing where daps and conversations used to take place.

47

A Lifetime In a Day

Edmund Reske

When sun first dances on the eastern shore To waltz with waves like many days before, Gold rays have cut back weary, dying night, And triumphs of the day may take their flight.

A long-used bed in which an old Man stirs: So many years have passed before his eyes. He wishes for his friends, whom he outlived, And family too, now of them he’s deprived.

He rushes out to meet the glorious dawn, A Boy who to the sunny day is drawn. He can’t resist the urge to use the day And disregards his sister’s plea to play.

Now Sun has loosed Horizon’s loving hand. Though separate, still nearby the partners stand. But now released to give her fullest glow, Great warmth she gives, a gift to all below.

The yearning Man has wished his day were done So that he could not see the shining sun. His hip forbears a venture out his doors, Confined in grief to stuffy walls and floors.

While running down the sidewalk towards a ball, A bitter stone pulls Boy into a fall.

His knees now red, his tears begin to swell, He cries for loss of light, not ’cause he fell. The light has turned from white into a gold, Night’s shadows see the time and grow more bold.

King Midas laid a finger on the sky.

Sun’s rays will nigh in wondrous glory die.

48

Awaiting sleep’s relief are Boy and Man. Akin they are, both past the daylight’s span. Unwilling, yet one drifts off in a thought, And Man’s attempts at sleep all come to naught.

Soon light will turn her head upon the west. Now troubles of the day may take their rest, For Night has spread his cloak across the sky And waves, without a partner, now may die.

Again sun dances on the eastern shore To waltz with waves like many days before. Gold rays have cut back weary, dying night Past sorrows deep are gone and set aright.

49

Evan Mullins photograph

50

Alex Keuss photograph

The Flaw in Time’s Manner

Brendin Keutzer

Time marches forward

To see the rise of a nation

And also the fall

Time marches forward

And so I wait

For time to tick in my favor

For time to tick a little slower

For time to tell me who I am.

As the clock stops ticking for one beat

I remember two things about who I am

I am forever searching.

I am forever lost.

And in this beat I find a false god who tells me I am whole but

I am forever searching.

I am forever lost

Behind red curtains, thorny barricades, mossy stonewalls, and clear-rose doors.

So I let time tick forward.

I let time tick till the minute hand snaps

And the numbers corrode to ash.

I let time tick till the hourglass breaks

And the sand turns to dust.

I let time tick till the right second

To open the doors.

To climb the walls.

To break the barricades.

To tear the curtains.

51

But with time comes war.

With time the ash will reform into fiery volcanoes

Used to shoot iron magma into the sky.

With time the planets collide with a passionate crash

Used to create a panic so noiseless, so deafening.

With time, galaxies distance themselves so far apart

Supernovas collapse alone,

And black holes leach upon dark empty nothingness

Until the universe reverts to a time before what’s known.

But still I wait, and Time marches forward.

52

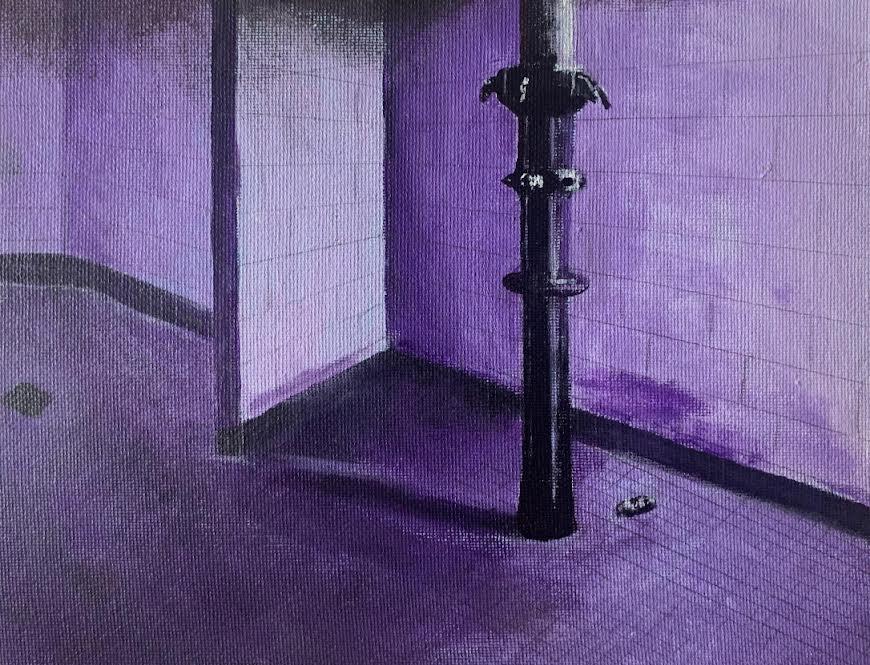

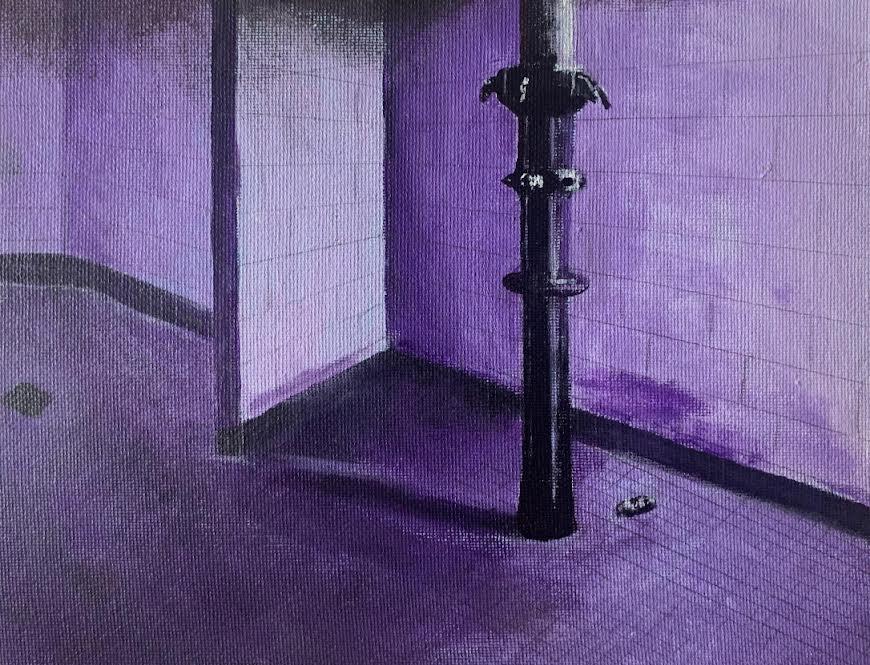

Sam Besmer painting

An Interior Window

Andrew Moffett

My soul is a stained glass window And I am a cedar standing near.

My will blows where it will, Sighing at the Word of the wind.

Light softly dances over the cool sanctuary floor Beyond the slender juniper and seasoned glass. Gold and azure melt into jade and blood red, And the stars and the stones are one.

What are windows but the panes For pilgrim light to pass through?

The will shifts.

Shady whims of graying limbs dilute the prayers

Offered up through my prism window.

Swaying cedar beams mute the Word of the Sun, Warmth blends and bends to sullen charcoal. Broken shafts and bitter shards bar the source Of my lonely little room.

The wind shifts.

One day that tree will be hewn into a Cross.

53

Charge

William Miller

Nervously I sit and wait, My Enfield clutched at my right. For untold horror awaits us all On the barrier of night.

I hear a puking from behind, And to my left I see One who shakes, and to my right A man and rosary.

As I stare at my gas mask now, It seems to look right back, A reflection of my present self, The purity I lack.

I close my eyes to calm myself, But to no avail.

I need not comrades to inform me Of how I’d turned pale.

Rain comes down like bullets now Accompanied by shells, Foreshadowing how my life has now Become a living hell.

Anticipation kills us all As anxiously we wait. The rain has soaked our clothes and boots In a miserable state.

The general and pocket watch Will signal our advance. Will we survive or perish here? Do we even stand a chance?

Mud has caked our war attire, But our sanity we keep.

When suddenly, the distinct sound, The long-awaited “Tweet!”

Then all at once the crowd yells And hop the slippery hill. All of us are terrified, But we press harder still.

Gunfire plagues the misty air And mows the first row down. Thankfully, the thunderous shells

Make foxholes in the ground.

Constantly the metal shower

Drenches the wet terrain; The men we lose, the casualties Are every bit insane.

On and on we push upfield, Keeping steady pace, And after a few hours, we Have reached the German base.

They do not give up easily Nor do they ever quit, But try as they might, we win the day And take their wretched pit.

Looking back, what was it for? We only gained a mile. Was all this fear, was all this death Really worth the while?

Life and death I ponder now, Both of which I fear, Because of how this war changed me, Who was the victor here?

54

in the way

Jay Carroll

maybe my poetry is in the way of my work but it doesn’t matter, i’ll ignore it for as long as i can because i’m committing to something whether it’s beneficial or not.

see me and you are different, i speak about frank shanking me or father frantic being a fraud or the score marks on wrists or the speed of someone walking in the hallway or

only being able to describe my love with sentences that rhyme or that one girl who met my mom over the summer or sophomore sanity or the feeling of the summer fling “static” or the usage of the word very or color (and the lack of) or being loose or

what was allowed and what wasn’t or typo(s)

my tone of tongue is eloquent in the way

that not everyone can see but what if that’s the way it’s meant to be

the persisting emotion of anger staggers in the back of my mind interesting because i’m never mad anger is just in the way

i’ll strive at what i consider striving for me so many goals but never enough time wanting to pursue so many professions almost there but not quite yet because my poetry is in the way

read me up and read me down and at the end, you might have a frown damn you might even shed a tear so when you read me make sure no one is near and if you can’t read me, that’s okay because it might just be me that’s in the way

55

Meditation on the Mundane

Lorenzo Gutting

What are we to do today

When all the world around is gray?

Sitting alone within the mud

Where neither thoughts nor flowers bud.

Above the mud, there is a voice And so you listen without a choice.

Heed these lessons is what they say, Or else you’ll fail again some day.

Keep us busy with meaningless tasks, And endless, endless, endless asks.

They make it so you have no time, And tell you “go and make a rhyme.”

But there is no rhyme, there is no reason In the depths of this dark season.

Lost within this endless night, The never-ending end’s in sight.

Amidst the noise, a quiet plea, A longing to just simply be.

To find a moment’s fleeting grace, Relax inside silent embrace

56

For solace in the crowded void, In stillness, not to be destroyed.

Pages turn, none remember, Yet in the coals, there is an ember.

Among the darkness, a silent light Calling out for us to fight

To light the path and show the way And find our light amidst the gray. watercolor

Matthew Kleinberg

Matthew Kleinberg

57

When You Can’t Sleep

Frank Kovarik

Think of a commercial that your grandpa didn’t like.

Think about the longest ride you’ve taken on your bike.

Make a list of all the birds whose songs you recognize.

See if you remember all the times you won a prize.

When you’re up at night and you can’t sleep,

Think of all these things instead of me.

Take a mental walk around the house where you grew up.

Imagine that you’re pouring coffee in a giant cup.

See if you remember all of the Apostles’ Creed.

Think about the novels that you’ve always meant to read.

Don’t think of me; that won’t help you back to slumber.

Count your blessings, count some sheep, whatever you can number.

Find something kind of boring, something you can set your mind to,

And if you start to think of me, well, babe, let me remind you

That I never had what it would take to be just what you wanted. You deserve the best, but instead you got me, honey.

All I can say is sorry and I hope that you forget me.

No, I don’t want forgiveness; just forget you ever met me.

Think about some chords that you could play on your guitar. You tried to teach me, but I never took it very far.

Try to reconstruct a day when everything went well.

Don’t think about the day when you told me to go to hell.

When you’re up at night and you can’t sleep, Keep it shallow. Don’t get in too deep.

Don’t think about the years we were together.

Think of something boring, like the weather.

Take some deep breaths, let go of your tension;

There’s nothing about me that’s worth the mention.

When you’re up at night and you can’t sleep,

Think of all these things instead of me.

58

Christian Blonde

59

collagraph plate

60

photograph

Tristan Kujawa

SunShine StoRkS

The Infant Account

Jake Fitzpatrick

He’ll be like any other baby

A hospital paycheck

A mouth to feed

A ball of sickness

The cause of many sleepless nights

Soon to become a grumpy teenager

Soon to have no job

Nothing at all

Nope.

He’ll be distinct from you and me

A son and loving brother

A friend to many

A ball of laughter

The cause of countless memories

Soon to be a flourishing student and performer

Soon to be a pioneer in every path of life

The reason that we choose life.

61

The House

Henry Eichhorn

62

The slouching house shudders to life, Whistling through cracked lips, a sunken porch step, a split shingle, a crooked door. The rusty porch swing squeaks in greeting as two pairs of youthful footsteps cross the verandah.

The house creaks, it groans.

Song echoes through barren halls, accompanied only by the rhythmic shuffle of footsteps. A pair of shadows dance across the empty room,

Growing and shrinking,

Swaying to the sound of the warbling song.

The floorboards cringe under their weight, gasping for air as they occasionally break the trance of the scene before them.

The house creaks, it groans.

A respite of quiet fills the darkened house.

The two pairs of footsteps creep past the closed door, attempting to reach the haven of their room.

A sudden squeak, a held breath.

A familiar wail builds, A pair of sighs respond.

The tired footsteps double back towards the door.

The house creaks, it groans.

Silence

Dripping, suffocating silence

It envelops every corner, every room.

It is slow to action, hollowing the mind, Building dread, anxiety.

It feels heavy, crushing, overwhelming. There is no escape from it,

One pair of footsteps desperately fights off the beast, whispering down full halls.

The couch lets out a sigh, its cushions sink, caving in towards the center.

An occasional scrape and ring of silverware cries out into the silence.

The silence stings, burning at the ears like a cold breeze.

A lone heartbeat, the body’s attempt to shatter this dangerous cold, can almost be heard, Yet there is no escape from it.

The silence muffles all but the mind.

A chair scratches against the worn floors, carelessly etching its path across the room. It wobbles, whining under the immense weight.

The chair clatters, The rafters screech, The room falls silent.

The house creaks, it groans.

63

photograph

Andrew Moffett

This Pen (On the Closing of a Chapter)

Tim Browdy

64

after “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” by Robert Frost

Sharpened through by age fourteen I put down the pencils, those useless yellow woods, at which new age are decayed, frozen, shriveled, no longer lovely. So from said point I rid of doodles and picked up my dark pen. With writing to be had and works to deFrost, my black and blue shovel began to cut deep.

Through fifteen this pen went dry, was used but twice when required. But when I rid of such sophomoric markings, this pen began to have a life of its own—curiosities, failings, advocacies, promises, ink-filled endearments. With mind and paper, this pen dragged me to my oak-stained desk, the one my room alone must keep.

Though through eighteen this pen fights harder now than ever and though it’s weathered numerous snows, I must go now. This pen will take me miles from home—from harnessed horse to farmhoused wood; here, the places my pen and I must go. If our resin runs dry or our bodies sweep limp before my letters reach home, forget not the chapters this pen and I wrote. Forget not this pen’s darkest evening has yet to sleep.

Matthew Kleinberg

Matthew Kleinberg