Symmetrical Bodies

SUSAN

R. JOHNSON

February 3 – March 7, 2025

Gallery

St. Mary’s College of Maryland

St. Mary’s City, MD

SUSAN R. JOHNSON

From the Domestic to the Glamorized

— Saul

Ostrow

To document a world that closely resembles our own, yet seemingly exists in another parallel dimension, artist Susan R.

Johnson adopts the personae and methodologies of the “cultural historian,” “archaeologist,” and “anthropologist.” In her work she accomplishes this by collapsing various disciplines we use to understand ourselves and the worlds we occupy into one another. Meanwhile, her diverse interests, experiences, and educational background, which includes an MFA in Painting and Printmaking, as well as studies in psychology, creative writing, and advertising, all of which inform her multifaceted content. Likewise, Johnson’s background as an amateur naturalist is the source of her fascination in the Age of Exploration’s obsession with documenting and controlling nature for commercial purposes. This interest in cataloging and categorizing, has provided her with a framework upon which to build her critique of cultural norms, which is a central theme that runs throughout her artistic production.

In such long-term projects as The Alternate Encyclopedia (1995–2012), Johnson set out to examine how humans represent their understanding of themselves within nature and culture. In turn by questioning our established perceptions of reality and its taxonomies the “Encyclopedia” formed the foundation for her exploration of consumer culture. As her work progressed, Johnson’s critique became focused on specific aspects of consumer culture. With time it has become a critique of our societal expectations of a woman’s role as homemaker, companion, status symbol, and accessory, as well as forming a museum housing the products of an eroticized world of patriarchal fantasies. In doing this, Johnson’s art by avoiding the traps of over-determination and literalism, serves as a corrective to more essentialist understandings of consumer culture and gender roles. This is because Johnson’s works are more concerned with how in general societal and cultural structures shape human experience, understanding and behavior.

Structured like an old-fashioned natural history museum, The Alternate Encyclopedia consists of themed ‘cabinets of curiosities’ containing dubious historical objects and lost manuscripts. These documents, presented as the cultural remnants of some realm other than our own, record the human impulse to capture, collect, name, tame, dominate, and reorder nature. To make this all believable, Johnson interweaves actual, simulated, and fabricated images together into a seamless fiction. She achieves this by combining disparate elements to expose the truly Kafkaesque nature of the world we live in, where strange and disconcerting scenarios of consumer culture are normalized and made desirable. Its realism is reinforced by her ability to blend trompe l’oeil elements with those of magical realism.

Expanding on these ideas, her next big project was Ready-Made Dream (2013–18), which though it differs from The Alternate Encyclopedia in its conceits, also challenges the way we understand the conventions of our consumer

environment. In this work she presents fact as fiction. Depicting a universe of domestic abundance and convenience, this seemingly benign installation features larger-than-life Pop-ish displays of images of goods. Accompanying these bright, shiny objects that deny the planned obsolescence built into them are crisp diagrams that graphically map and meticulously catalog every item. Though the reference here seems to be mail-order catalogs and the display of merchandise, Johnson exploits the institutional standards of museum display and the systems by which things are inventoried and archived. As applied in this work, this approach evokes a hyperreality reminiscent of the stylized world found in Wes Anderson’s films, such as The Grand Budapest Hotel and Asteroid City

where he employs plausible mise-en-scènes rendered in a vibrant color palette to create simultaneously a sense of heightened reality, artifice, and fantasy. It is through these filters that Johnson would have us reconsider the promises of the post-World War II American Dream and its continued impact on our everyday lives and culture.

Conceptually, Ready-Made Dream not only sets the stage for Johnson’s future works, but also marks a significant technical shift, as it’s her first using of high-resolution scans of imagery taken from mid-20th century magazine advertisements. This technique becomes central to The Hall of Portraits from The History of Machines (2018–22), where Johnson manipulates these images to create surreal hybrid figures. While Ready-Made Dream explores the broader landscape of consumer culture and its promises and deceptions, for “The Hall of Portraits” she narrows her focus to examine specifically the impact of consumerism on women’s identities. This transition from a macro to a micro perspective allows Johnson to delve deeper into the gendered aspects of consumer culture. For “The Hall of Portraits,” Johnson envisions a version of The Stepford Wives that goes beyond mere drug-induced compliance. The women who populate “The Hall of Portraits” are adorned with forever smiles and embody a matriarchal notion of status, pride, and domestic bliss. They are surreal portraits that blend elements of domestic products with fashionably dressed female figures, representing a visual commentary on the male fantasy of mechanizing and objectifying women. Though slyly humorously, these images serve as a pointed critique of the retrograde concepts of feminine desire and expectation that continue to be promoted to this day.

Subsequently, though Johnson’s imagery is drawn from advertisements and stock photographs, her content is drawn from her own experiences and observations as a woman navigating societal expectations and constraints in both her private and public lives. Upon this foundation, Johnson seeks to re-imagine how women of her mother’s generation experienced issues of identity in an era when they were unabashedly seen as both the consumer and the consumed. Through her creation of “alternate pictorial histories” and encyclopedias, Johnson expresses a personal desire to challenge established narratives and categories, connecting her own experiences with those of previous generations. While not overtly autobiographical, it is

clear that her personal experiences, observations, and interests play a crucial role in shaping her artistic themes, approaches, and critiques of society and consumer culture. In this manner, Johnson uses personal and collective female experiences to create works that invite viewers to reconsider their perceptions of gender roles and expectations in modern society, effectively weaving together individual stories with broader societal narratives.

Given her content is rooted in personal experiences and societal observations, Johnson finds a powerful resource in the techniques pioneered by earlier artists who used visual media for social commentary. This connection between personal narrative and broader artistic traditions is particularly evident in John Heartfield, who used photomontage as a potent political weapon, Johnson adopts similar techniques in the digital realm. Heartfield was a German artist and member of the Berlin Dada movement who became renowned for his anti-Nazi and anti-fascist photomontages. His innovative approach combined photographs, text, and graphic design to create biting satirical commentary, setting a precedent for using the new mediums of photography and commercial printing as tools for social critique. Johnson uses digital technology to adopt similar techniques, subtly incorporating sophisticated digital manipulation into her work that she combines with hand-painted passages.

In her series Hall of Portraits from The History of Machines, Johnson employs digitally assisted photomontage to realize male and consumer culture’s vision of glamorized yet stereotypical female roles. These montages are made from fragments taken from a wide range of product and fashion advertisements, digitally melded into integrated images that combine differing levels of pixelation. At a distance, the resulting images appear seamless, but like Frankenstein’s monster, they reveal their fractured nature upon closer inspection. In keeping with their medium, these works come in a variety of formats ranging from carte de visite-like post cards to monumental-scale banners.

Recently, Johnson has taken to using digital technologies as a means to recycle her own imagery. The Symmetrical Bodies project (2023–25), presented in this exhibition, builds upon imagery drawn from her recent series: Les Célèbres,

The Headless Woman, and The Curiouser Groups. Each of these series, in turn, besides addressing some aspect of female identity, has a subplot; Les Célèbres originates with the notions of self-fashioning — the process of constructing one’s identity and public persona to reflect cultural standards or social codes. Meanwhile, The Headless Woman references the title of Surrealist Max Ernst’s collage novel La Femme 100 tetes (1929) and indicates her interest in creating dialogues between historical works and contemporary issues. The Curiouser finds its inspiration in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) in which her adventures become curiouser and curiouser and indicates Johnson’s interest in exploring themes of reality and perception. This layering of associations and references, which runs throughout much of Johnson’s work, are not so much meant for the viewer to decipher as they are traces of her thinking processes. Meanwhile, Symmetrical Bodies also marks a significant evolution in both concept and aesthetics, extending her exploration of the complex network of sublimated narratives that comprise female identity.

Unlike The Alternate Encyclopedia and Ready-Made Dream, which focused on critiquing consumer culture and societal norms, Symmetrical Bodies draws inspiration from the ideal of bodily symmetry, an unattainable perfection and beauty that contrasts with the reality of human diversity. While maintaining her core themes, her medium’s ability to out-put in different formats, these works differ significantly from one state to another. Seemingly this is because their images are less overtly narrative and as such their materiality effects their aesthetic content. As post cards and in painting formats they appear to be realistic renderings of women — little more than portraits. The figures alterations are not immediately apparent, yet they seem strangely unnatural. But when they are digitally printed onto unstretched gossamer scrims that barely hold their silhouetted images the resulting over-life-size centralized forms evoke the effects of color-field painting and have a more sensuous effect than her previous works.

By focusing on representations of idealized women, Johnson’s work continues to employ the feminist strategy of making the personal political, exemplifying the ongoing relevance of the feminist critique of society’s patriarchal structure and its representations of women. This approach builds upon the legacy of pioneering intersectional feminists who address multiple, overlapping systems

of discrimination like the artist Martha Rosler, who is best known for combining images from glossy home magazines with photos from the Vietnam War to create jarring juxtapositions during the Vietnam War era. Johnson’s implicit critique that satirizes consumer culture, societal ideals, and aspirations, not only sustains this feminist tradition but also adapts it to address the complexities of contemporary society under current cultural and political conditions.

While deeply rooted in feminist critique, Johnson’s artistic vision extends beyond gender-focused discourse to encompass broader cultural commentary. This expansion is particularly evident in her connection to British Pop artists, who similarly challenged societal norms and consumer culture. During her studies in London, Johnson became aware of British Pop artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi and Peter Blake. However, it is Richard Hamilton, regarded as the father of Pop Art, who appears to be the most significant influence. Hamilton’s definition of Pop as “Popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business” resonates with Johnson’s work.

Like Hamilton’s, her work often employs collage techniques to juxtapose elements from consumer culture and popular media. This is particularly evident when comparing her approach to Hamilton’s groundbreaking 1956 collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? With this work, Hamilton satirically comments on materialistic desires and the fantasy of the perfect American lifestyle by inserting a nude pin-up and a bodybuilder holding an oversized Tootsie Roll Pop into a modern living room setting. The scene also includes such things as a large-screen television set, a vacuum cleaner, and a décor consisting of corporate logos and comic book images. The juxtaposition of these elements creates a domestic environment that both critiques and celebrates the post-war consumer culture being marketed to the world, a technique that mirrors Johnson’s own artistic approach. Although almost 70 years separate Hamilton and Johnson’s works, their critiques continue to serve as powerful reminders that in our increasingly surreal and consumer culture-driven world, we must question, deconstruct, and be vigilant of the ideals embedded in the images that surround us. This latter point is central to understanding Johnson’s work.

The connection to Hamilton and to the critique of consumer culture provides a foundation for understanding Johnson’s work through the lens of critical theory, in particular Walter Benjamin’s the Arcades Project and his concept of the “dialectical image,” where historical artifacts are juxtaposed to reveal hidden relationships within society. In doing this, Benjamin sought to disrupt conventional, linear views of historical progress and awaken political consciousness. By re-presenting the conflicting societal expectations of consumer culture, Johnson’s approach creates a critical commentary on the evolution of women’s image as commodity, as it moves from domesticity to being stereotypically glamorized.

Furthermore, Johnson’s artworks exemplify Benjamin’s theories on art’s transformation in the age of mass reproduction. Her pieces, though output as hard copy, in actuality primarily exist as digital files. This permits endless reproduction in various formats and scales. This approach directly illustrates how technology and mass reproduction are reshaping the relationship between art and society. In turn, Johnson’s practices are in accord with Jacques Rancière’s views concerning the reorganizing of the aesthetic realm.

By manipulating and recontextualizing mid-20th century advertisements, Johnson challenges the “distribution of the sensible” — the normalized perceptions crucial to maintaining societal norms. Her art effectively disrupts established views of women’s roles and identities, creating a “dissensus” — a rupture in common understanding to reveal hidden societal relationships. She does this by merging familiar elements in unexpected ways, particularly focusing on how the representation of women manifests domestic ideals depicted within glamorous stereotypes. In doing so, they promote restrictive gender norms in compliance with an idealized uppermiddle-class domesticity. Subsequently, while exposing the “police order” that maintains traditional gender roles, values, and consumer expectations, Johnson’s transdisciplinary approach brings repressed aspects to the forefront, making them more visible, audible, and thinkable.

While Johnson’s visual techniques effectively critique societal norms, her approach also resonates with broader feminist literary theory. Specifically, her subversion of the visual language of consumerism can be viewed as an application of French writer and feminist literary theorist Hélène Cixous’ conception of écriture feminine (women’s writing) to visual art. Just as Cixous calls for women to develop their own modes of self-representation in writing, Johnson creates a visual language and literary conceits that seek to do away with the “unified, narcissistic (male) subject” that contributes to the repression of women. Meanwhile Johnson’s use of mid-20th century source material also reflects the philosophical concepts of Hannah Arendt, who, influenced by Walter Benjamin, sought to recover the lost potentials of the past. Arendt’s approach

involves identifying moments of historical rupture and dislocation to create a more holistic understanding of history and society by connecting supposedly disparate elements and ideas.

To effectively bridge the gap between feminist literary theory, social philosophy, and visual art, Johnson seems to have channeled Arendt’s view that to confront contemporary issues, we can no longer rely on concepts or morals that have been rendered inadequate by the events of the 20th century. Subsequently, Johnson’s practice of reimagining women’s experiences across generations brings to mind Arendt’s emphasis on the importance that storytelling and imagination play in understanding our political realities. Arendt believed that storytelling could help us make sense of our experiences and create meaning in a world where traditional frameworks have broken down. Similarly, Johnson’s work uses visual storytelling to reframe and reinterpret women’s experiences, inviting viewers to engage critically with both historical and contemporary representations of femininity.

By creating alternative histories and modes of expression that draw on diverse disciplines and histories, Johnson’s work forms a “framework” to expose, comprehend and critique the sexism embedded in our ideals and iconography. By recovering lost or overlooked perspectives, Johnson not only focuses on women’s experiences in consumer society but its correspondence in the realm of mass media. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of how over time, societal norms and expectations have shaped women’s roles and identities. By questioning and re-imaging these constructs, her work confronts the ofteninvisible structures that influence our conceptions of women-hood, domesticity, glamour, and ourselves. To do this, she continues to push the limits of her modes of presentation, thus reaffirming art’s role as a medium for exploring complex social issues and as a potential catalyst for cultural change.

Mining the archive is like building a time machine; I look at the material culture of the past as a way of understanding what has come into being in our contemporary times.

Symmetrical Bodies, 2024

The Curiouser Group No.7 dye sublimation print on flag fabric, 72 x 51.5 in.

Symmetrical Bodies, 2024

Following pages 16 & 17: The Curiouser Group No. 13 and No. 14 dye sublimation prints on flag fabric, 72 x 51.5 in. each

Bodies, 2024

Symmetrical Bodies, 2024

Following pages 24 & 25: The Curiouser No. 22 and The Curiouser No. 23 dye sublimation prints on flag fabric, 72 x 51.5 in. each

Symmetrical Bodies, 2024

Following pages 26 & 27: The Headless Woman No. 3 and The Headless Woman No. 20 dye sublimation print on flag fabric, 72 x 51.5 in. each

Susan R. Johnson earned an MFA in painting and printmaking from Columbia University and a BFA in painting from Syracuse University. She has been awarded fellowships from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, NEA/Mid Atlantic Arts Foundation, New Jersey State Council on the Arts, Virginia Commission for the Arts, a Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Professional Visual Art Fellowship, and four Individual Artist Awards from the Maryland State Arts Council. One-person exhibitions have been organized by the Pitt Rivers Museum, Tweed Museum of Art, Jan Cicero Gallery, Delaware Contemporary Art Museum, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, University of Richmond Museums, Eleanor D. Wilson Museum and the Midwest Museum of American Art. She has been awarded artist residency and library research fellowships by MacDowell, Cité Internationale des Arts, Golden Foundation, Art Omi, Millay Arts, American Philosophical Society, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, Kohler Arts/Industry, Tyrone Guthrie Centre, American Antiquarian Society, Rosenbach Museum and Library, Visiting Artist and Scholars Program/American Academy in Rome and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Reviews of her work have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Brooklyn Rail, The New Art Examiner, Partisan Review and Art Papers. Johnson’s work is in numerous public and private collections. She is currently a professor of art and department chair in the Department of Art, St. Mary’s College of Maryland where she has served as the Steven Muller Distinguished Professor of the Arts and was awarded the Norton T. Dodge Award for Outstanding Creative and Scholarly Achievement.

Saul Ostrow is an independent curator, consultant, and critic. Since 1985, he has organized over 80 exhibitions in the US and abroad. His writings have appeared in art magazines, journals, catalogues, and books in the USA and Europe. In 2010, he founded along with David Goodman and Edouard Prulehiere, the not-forprofit Critical Practices Inc. (criticalpractices.org) as a platform for conversation on social and cultural practices. He has served as Art Editor at Bomb Magazine, Co-Editor of Lusitania Press (1996–2004) and was Editor of the book series Critical Voices in Art, Theory and Culture (1996–2006) published by Routledge, London.

Acknowledgments

The Boyden Gallery is honored to host this exhibition, and we appreciate the assistance of the artist on the selection of work. Special thanks to Saul Ostrow for his insightful catalog essay on Johnson’s work in the context of contemporary art and culture and to Susan Bowman for her stunning catalog design.

The artist wishes to thank Britney Fowler, who served as a special exhibition assistant to the artist, the Boyden Gallery student assistant team, and Dr. Katy Arnett, for facilitating the addition of this show to the Boyden Gallery's schedule this year.

This exhibition and catalog were made possible in part with funding from the Maryland State Arts Council and the Arts Alliance of St. Mary’s College of Maryland. The development of the artist’s work in this exhibition has been supported by Faculty Development Grants from St. Mary’s College of Maryland, a Maker-Creator Fellowship from the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, and a residency fellowship at Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, France through the Virginia Atelier.

Photography

Courtesy of the artist

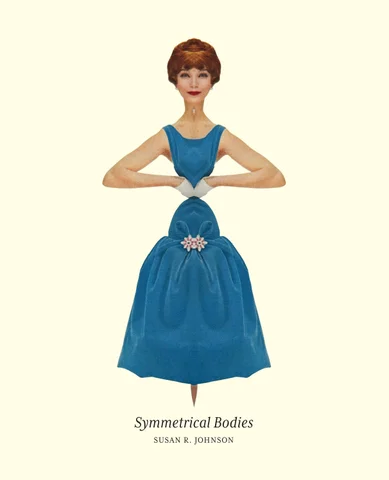

Front cover

Symmetrical Bodies, 2023, The Curiouser Group No. 16

Back cover

Symmetrical Bodies, 2023, The Curiouser Group No. 11