10 minute read

IN CONVERSATION

A new age of social justice

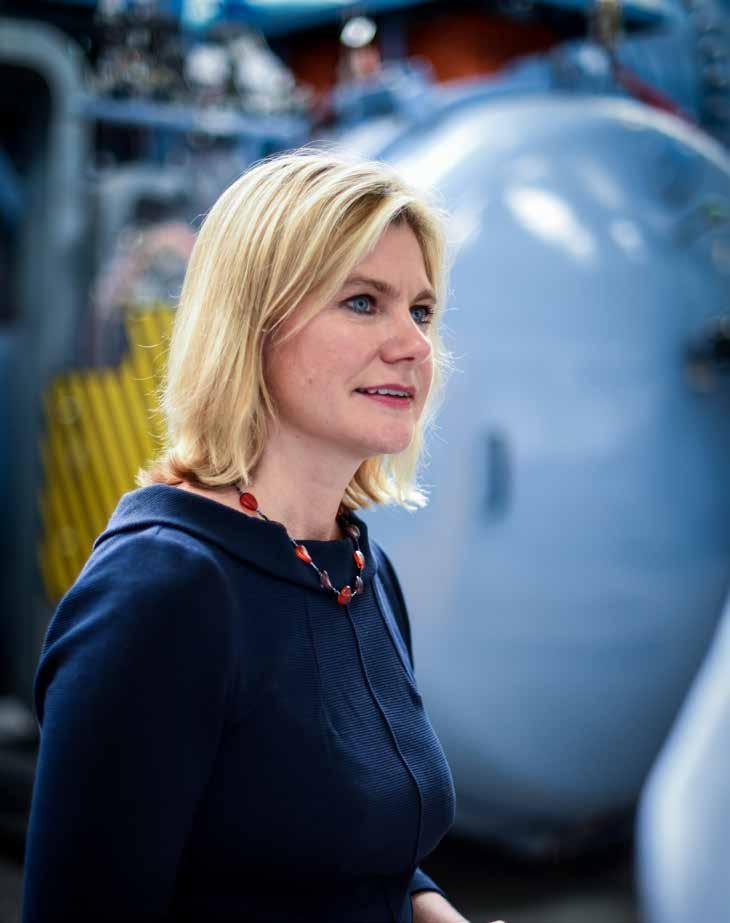

Rt Hon Justine Greening talks to Big Issue founder Lord Bird about the way ahead for the social justice agenda.

Lord Bird, is founder of the Big Issue and a longtime advocate for driving social mobility. Since he co-founded the magazine in 1991, it has provided life-changing support for some of our country’s most vulnerable people. In 2018 he also helped to create the Social Mobility Pledge, working closely with the Rt Hon Justine Greening. They discuss social justice in the context of coronavirus and the opportunities it presents to turning a corner on homelessness.

JG: One of the things to come out of lockdown was the speed at which everyone had to suddenly confront a range of issues, whether you’re runnning a business, looking after your family or in the health service - but also for homelessness. It was striking that within a matter of days, solutions were found for people for whom years had been spent trying to get a life changed. It feels to me like this is a moment where we’ve got some decisions to take about trying to get better outcomes for some of those people that we desperately want to see get help.

LB: That is the interesting point. What is really exciting about this is that we have had a situation for decades [then] we very quickly lost all of the country’s rough sleepers, probably about 90 per cent which is about 5000 people. To me what is exciting is the speed with which government can work when it uses the facilities of the homeless organisations. The government didn’t actually lift [the people] themselves but it commissioned lifters. People like St Mungo’s, Crisis, Centre Point et cetera. They very quickly said ‘we’ve been giving you money for years, to help people survive on the streets, now we are giving you money to lift them off the streets and then we’re going to pay for the Travelodge bills and we’re going to support local authorities who have been the biggest source of support.’ But the real problem for me is what we do afterwards. We’ve managed to get agreement from [homelessness tsar] Dame Louise Casey and the Minister for Housing that they will not allow people to return to the streets. So we’ve got those green lights and hopefully they don’t have to go back onto the streets. My problem, and this is where social mobility is a really important ingredient, is that a lot of people’s prosperity is about to be destroyed. If you look at what the Local Government Association [LGA] reported recently, that there are about half a million people who will not be able to pay their mortgages or rent. That frightens the life out of me.

JG: So there are two groups that we really need to be concerned with, one is people that were already rough sleeping and homeless before we found a temporary assistance for, but the question is what next. And then you are saying, because of the downturn, there is a danger that we have a massive influx of new people that add on to those numbers that were already there.

LB: What we’ve got is ordinary people living comfortable lives, people who put all of their efforts and all of their eggs in the property basket or into bringing up their children. They are now passing into a place that we need to support them so that they don’t enter the mechanism, the system of homelessness and homeless decline. The LGA will be left to take those children and families and put them into B&Bs and find other transitional temporary accommodation or they will put them on a social housing scheme. So we have to reach out to those half a million and that is exactly what the Big Issue is now orientating itself for. We are becoming bigger players than we were before in homeless prevention. JG: And the work you are doing in the House of Lords now, driving the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill, is also about getting upstream and stopping problems before they even happen. Tell me more about why you’ve ended up being so involved in this.

LB: I entered the House of Lords with a proviso that I was not going in for any other reason than to, as I graphically described to one newspaper, cut the throat of poverty. What I was really saying was that I was not there to help people through the days, weeks, months and year, upping benefits. I wasn’t there to do any more than find the mechanism for dismantling the problems that produce social immobility because that’s what were dealing with. I was very, very concerned that I needed to find a way of identifying problems and moving forward.

JG: Do you feel like the Lords and Parliament more broadly has really seized on this enough? I was awestruck in the House of Commons at how few MPs were really engaged with social mobility day-to-day. So they might look at a particular symptom of the problem but I remember having a debate in Westminster Hall on how the Treasury needed to reform [to improve] social mobility, and there were about four MPs there. I remember the opposition had a debate on social mobility at the back end of last year and I think there were three MPs on the government side. It does seem to me that there is an issue of a lack of urgency in all of this and people have almost got used to the slow pace of change when actually they should demand much faster progress.

LB: What I find so difficult is that the greatest enemies of social mobility are people who themselves are socially mobile. When I talked to some MPs and some members of the government about social mobility and they all say that [welfare] support is much more important. I was saying in a debate the other day that we have to increase social mobility, very much based on what is happening in Wales where the Future Generations Bill there is asking many many questions about the quality of education, social delivery and people in need. I said we need to up social mobility, and a number of people in the House of Lords unified around the very idea that social mobility is not all it’s cracked up to be. But 90 per cent of people in Britain, and the British middle classes, have come from a socially mobile background. Therefore social mobility is the very bedrock of our modern democracy.

62 ‘

This is a moment to decide what kind of Britain we want to open up again ‘

JG: Social mobility is a right. People should have a right to make their own way in life unhindered by circumstances or background. It’s telling that we’re still even having to debate what I think is the very fundamental but obvious point that where you start and drove you to be strong and take on your education. I didn’t in this country should have no bearing on how far you can get. have a mother like that - I had a mother who wanted me to get What’s fascinating to me is that there’s a view that it’s almost a out to work as soon as ‘effing’ possible. What is interesting to me zero-sum game. In other words, if we allow more people to get is that we all have to sit back and realise that if we don’t get it from opportunities, then other people have to do worse. I think that’s mum and dad, and that is the best way of getting it, we’ve got to a false dichotomy. More people doing better lifts everyone at the get it somewhere. We have to have education that reorientates end of the day. There is a fundamental issue of how sustainable any the child who it has been let down by the opportunities that don’t society can be when gaps get so big. The [COVID-19] crisis does always come out of family life and reorientate them put them on feel like a genuine moment to take some decisions about what kind a better pathway. But I [also] think it’s terrible that our prison of Britain we want to open system does not redeem [and] up again. Because if we weren’t happy with the original one, and I certainly wasn’t, now is the time to refashion it. LB: I told a minister a few years ago that they were failing 30 per cent of our Interrogate yourself and find out what you’re doing and “ rehabilitate but often produces people who have been warehoused. JG: I thoroughly agree and I think if you were putting achieving social mobility and levelling up at the heart of government, then it would naturally children in schools. I [explained that] whenever I talk to people in the prison where you’re going turn you to look and direct your efforts at the people furthest away from a level system about how they did at school playing field and opportunities. And they all say they did very badly. When I of course that includes people in the talk to the working poor I ask how they did at school they always justice system, recognising that it’s not just their own lives that get say very badly. When I talk to A&E department and I talk to doctors lost because they are not able to fulfil their potential, [but there’s] there I ask what is the commonality of people here; and they say a greater cost to wider society. First of all the sheer expense of one of the real problems is that the NHS is clogged up with people people being in the justice system, but more importantly the who have not particularly done very well at school and they are opportunity cost of the fact that we never realised what they using the NHS as a drop-in because no-one has given them the could go on to do. chance to move on and address some of the issues around social One last question - what advice would you give to your mobility and social opportunity. That minister was you and we sat younger self? for an hour talking about how we could remove the barriers to social mobility. LB: I once said ‘don’t get caught’ but I don’t think I would give that advice now because I was caught and was given the JG: And we vehemently agreed that it was utterly unacceptable opportunity to make up for the poor family life that I had - a to have young people left behind before they’d even got into an violent, troubled domestic-abuse life. The advice I would give John adult life. I think that was one of those discussions that in a way Bird is a very simple piece of advice, and that is ‘question yourself, helped me realise there were a lot of other people around us in interrogate yourself and find out what you’re doing and where Parliament who felt exactly as passionate as I did about social you’re going. I spent so many years just floating and going from mobility and social justice. one crisis to another never realising that stealing that car might lead to imprisonment and all of that. But if I’d stopped and thought LB: That was an apocryphal meeting for me by the way. I know about it I might have then said what about learning to read and where you come from and that you had a mother who helped you write? What about learning some skills? I would have tried to make myself feel that actually I was a worthy human being and that if I put my mind to more constructive things I could be very useful to people.