70 minute read

Obituaries

For reasons of space it is sadly not possible to print all available obituaries in the College Report. In addition to the obituaries printed below, many others of recently deceased Somervillians can be found in the College’s Commemoration booklet available on the website at www.some.ox.ac.uk/alumni/news-publications

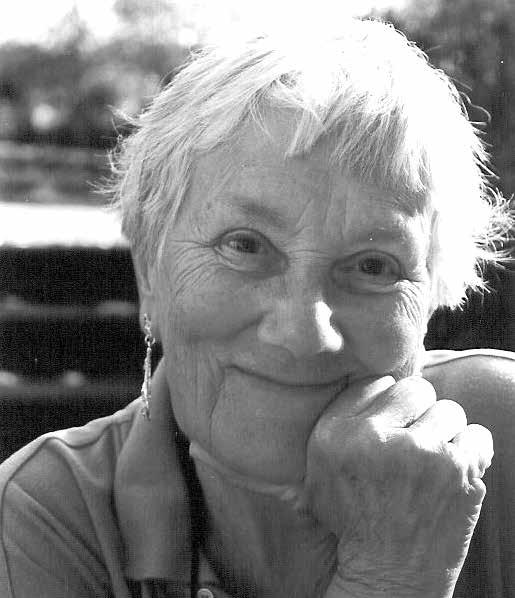

Jane Elizabeth Kister (Bridge, 1963)

Advertisement

Jane Bridge was known and loved by several generations of Somervillians – first as an undergraduate, then as a graduate and Research Fellow and finally as a Tutorial Fellow. But after 15 years of association with the college she met and married Jim Kister and spent the rest of her life in the United States.

Jane Bridge, born 18 October 1944, came up to Somerville as a Scholar in Mathematics from St Paul’s Girls’ School in 1963. She had just been diagnosed with Lupus and she missed much of her first year through illness. She restarted her degree in 1964 and thereafter was never held back by her health, although she lived with the disease for the rest of her life.

In spite of this uncertain start, Jane made many good friends in college and was socially always part of her matriculation year. Jane was a warm and empathetic listener, always interested in her friends’ lives and problems while making light of her own health concerns. The friendships she made in her first year at Somerville remained strong for the rest of her life. She made sure to get in touch whenever she and Jim came over to England and she managed to attend several gaudies as well as many social occasions with her group of friends, most recently in May 2019.

It was clear from the start that Jane was a very talented mathematician and this was recognised by her tutor, Anne Cobbe, who gave her inspiration and support throughout her undergraduate career. Jane had the ability to get straight to the heart of a problem and then to explain it with utter clarity; her written work was always beautifully presented in her italic handwriting. She was particularly interested in mathematical logic and always regretted that the Mathematics and Philosophy course was not available for her generation. After obtaining a First and being awarded a Junior Mathematical Prize, Jane stayed on to work for a doctorate, completing it under the supervision of Robin Gandy in 1972. She quickly became a key member of the very lively mathematical logic group, showing particular talent in managing the notably eccentric Gandy. Dana Scott arrived in 1972 as Oxford’s first Professor in Mathematical Logic and Jane worked closely with Dana to enhance the group’s reputation as a world leader. Jane was a wonderful mentor and big sister to all the students and research fellows.

Jane held the Mary Somerville Research Fellowship at Somerville from 1969 and, after Anne Cobbe’s retirement and subsequent death in 1971, she became the Fellow and Tutor in

JANE KISTER

Pure Mathematics. By this time she had already proved herself a very successful and popular tutor and she slipped easily into her new role in college as well as taking on new duties as a lecturer. After she had completed her DPhil, Dana Scott persuaded her to write the book Beginning Model Theory (OUP, 1977) as the first volume in the prestigious Oxford Logic Guides. This is a very lucidly written text, accessible to both undergraduates and beginning postgraduates with a background in either mathematics or philosophy.

In 1977, Jim Kister, a topologist from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, came to spend a sabbatical year in Oxford. Jane and Jim were married in July 1978 and settled in the United States. Jane soon became an editor at Mathematical Reviews where she remained for the rest of her career, rising to be Executive Editor in 1998 and retiring in 2004. Mathematical Reviews has traditionally provided short reviews of selected research papers and was a vital tool for academic mathematicians in the pre-electronic age. Jane’s mathematical ability and supreme administrative skills were perfectly suited to this work and she was heavily involved in the launch of the electronic version MathSciNet in 1996.

Jim died in 2018 after a long illness and Jane suffered a heart attack a year later, dying on 1 December 2019.

Anne Driver was born Anne Lyster Browne in Sowerby Bridge, Yorkshire. Her childhood was marked by the death of her father in a tram accident when she was two years old, an event which brought her closer to her extended family in Shropshire, especially her cousins and aunts. She was awarded an exhibition to study English at Somerville, and came up to Oxford in 1942, turning down the offer of a place at RADA. At Oxford she studied Old English and Norse literature, under tutors including JRR Tolkien.

She graduated in 1945, and after working for a local newspaper in Bath she turned to teaching, first at the village school at Chipping Campden (1948-1953), then Oxford Central Girls’ School, where she was Head of English (1953-1956). In 1957 she travelled to north India with her partner John Driver, who was studying Tibetan Buddhism. They spent three years living in the small town of Kalimpong, near Darjeeling, hosting a string of Tibetan exiles who had reached India over the Himalayas. Her two daughters were born there.

Following their return to England, she took up an appointment in January 1962 as an English teacher at Penrhos College, a girls’ school in North Wales, five months after giving birth to twin boys in 1961. While working full-time and caring single-handedly for her four young children in a large house in Colwyn Bay, she published three novels (under the pseudonym Anne Rider) with Bodley Head – The Learners (1963), The Bad Samaritan (1965), and A Light Affliction (1967), the last set in the Himalayas and re-published in the USA under the title Hilltop in Hazard. These drew on her experiences of life in Oxford, Rome (where she lived for six months in 1957) and India. A fourth novel, A Safe Place (1974), was published by Bobbs-Merrill in the USA.

Her writing was variously described by reviewers (including Anthony Burgess and Graham Greene) as ‘serio-comic’, ‘highly intelligent, ironic and most elegantly funny’, ‘taut, elegant and witty’, ‘surgically philosophical’, ‘totally persuasive’, ‘briskly elliptical’ and ‘deeply English’.

She moved to London and joined the English Department at Godolphin and Latymer School, Hammersmith, in 1967, staying there until her retirement in 1984. She was an inspirational teacher, taking an active part in school drama, running school plays, Shakespeare days, and drama competitions.

Retirement and the departure of her children marked a new phase in her life. She took adult education classes in art history, Italian and Finnish, and swam regularly. A deep commitment to peace and social justice led her to campaigning. She was a Greenham Common peace camper, and was arrested several times for non-violent direct action. Leading on from this she took part in Cruise Watch, a network formed to track missile convoys leaving American bases on regular road exercises, and was later arrested for sitting down in Whitehall to protest against the first Gulf War. She visited Nicaragua to learn first-hand about conditions in coffee plantations there, and attended an international women’s peace conference in Moscow, taking the Soviet hospitality with a strong pinch of salt and making a lasting friendship with the group’s official interpreter. She travelled widely, making a return trip to Kalimpong, and was a member of one of the first small western groups to travel to China from Pakistan via the Khunjerab Pass – including a stint on the back of a cement lorry. Above all, she devoted herself to her many grandchildren, by whom she will be sorely missed.

TABITHA DRIVER (1976)

ANNE DRIVER

Joan (Joanie) Emilie Philpott (Huckett, 1943)

Joan was born on 19 July 1925; her father was a doctor. She was educated at Doncaster High School and came up to Somerville in 1943 to read English.

Joan very nearly went to Edinburgh University. She had been offered a place at LMH, but was tempted by having seen the handsome medical students from Edinburgh who would regularly stay with her father. Ultimately she came around to the thinking that Oxford might have equal attractions but by then her offer from LMH had lapsed and she was found a place at Somerville.

In Oxford, Joan often visited the Moxley family, friends of her father, and through them was introduced to Peter Philpott, demobbed in 1946. They met on 9 November 1946 – it was love at first sight. They became engaged in 1947 and married in Doncaster on 23 August 1949. Initially living in Davenant Road in Oxford for the first three years of marriage, they supplemented their income with lodgers. Joan had got her Education Diploma in 1947 and between 1947 and 1952 she taught in Aylesbury and in Oxford.

For many years, Joan was busy bringing up a large family of five children. At the same time, she would often look after other children, treating them as extended family. She was consistently kind, caring and non-judgemental.

JOAN PHILPOTT

Once the family were old enough, Joan started receptionist work at the newly opened Geriatric Day Care Centre at Queen Elizabeth II Hospital in Welwyn Garden City, where she worked for many years. She thoroughly enjoyed caring for the elderly, regularly organising carol concerts and many other activities. She joined the casualty team as receptionist and, according to various GPs with whom she worked over the years, she had quite a hand in their initial placement training.

Joan had simple tastes. She has never been abroad, although she consistently maintained throughout her life that her visits to the Isle of Wight were undoubtedly abroad. She enjoyed annual holidays around the UK with her family, but would always say how nice it was to be home again.

Joan was a highly accomplished musician and pianist. She gained Grade 8 Piano and won many St Albans Music Festival categories over some years. At Somerville, she sang in the Somerville-Balliol Choir. Gardening was another pastime she thoroughly enjoyed. She and Peter shared a love of dancing, especially Old Time Sequence dancing, and for many years danced at various clubs. The last time they danced together was on Joanie’s 80th birthday.

Joanie died very peacefully in her sleep on 11 November 2019, at home and looking out onto her roof garden, as she wished.

It was amazing good fortune to have had 70 years of very happy marriage, having known each other for 73 years and 2 days.

PETER PHILPOTT Audrey Faber (née Thompson) died peacefully at home in Oxford on 2 July 2019, aged 93. She was born in Keswick, Cumbria in 1925, the only child of Eleanor (née Telford) and William Thompson, and educated at Keswick School before going up to Somerville in 1944 to read History. The college and her Oxford experience were profoundly important to her, especially after the death of her beloved mother from TB in 1945. In college she was taught by May McKisack, though preferred Oliver Cromwell to her tutor’s medieval home territory. Wider university life was at its most exciting in those years when many undergraduates returned from the war, and Audrey’s theatrical adventures included stage-managing Love’s Labour’s Lost (directed by Anthony Besch, with Kenneth Tynan in the cast) for the OUDS in her Finals term. A stern rebuke for making a noise late at night was all she recalled of her studious contemporary Margaret Hilda Roberts.

After university she trained as a teacher and taught history at Downe House School, near Newbury, before taking an opportunity to travel to Hong Kong in 1951 for a six-month working holiday. There she met Jack Faber, a structural engineer, and they married in 1953; they had two sons and a daughter, and for the next 30 years their house in Jardine’s Lookout was a constant refuge for visitors from all over the world.

Audrey continued to teach history, at St Paul’s College and elsewhere. Her strong Christian faith led to active membership of the congregation at St John’s Cathedral, running the Sunday School and then the Flower Guild, as well as helping to make mountains of fudge to sell at the annual Michaelmas Fair. Audrey always looked to help people, and importantly to find the ways in which they wanted to be helped. She was heavily involved in the setting up and running of Hong Chi Association (formerly the Hong Kong Association for the Mentally Handicapped, founded in 1965 by her great friend, Lady Bremridge); for several years she ran the library at The Helena May (the central women’s club in Hong Kong), and, with Jack, staunchly supported St James’ Settlement (a youth and community centre). They retired from Hong Kong in 1983 (though kept a base there until 1997) and settled in England near Chichester, where they continued to welcome visitors from near and far. Audrey quickly became an active member of their village church, serving as secretary of the PCC and a lay member of the local deanery synod. In 2006 they moved to Oxford, and to a new church congregation at St Margaret’s. She treasured her connections with Somerville all her life; having helped mark Daphne Park’s card for Hong Kong fundraising, she became a member of the College Appeal and the Somerville Association (alumni relations) Committees. Audrey was immensely proud of her Cumbrian roots, and of her family, and her love of history shone through her reading and her conversation. She is survived by their three children, William, Robert and Peglyn (Pearson), and three grandsons.

PEGLYN PEARSON

AUDREY FABER

Leonora Helen Goulty (1944)

Leonora Goulty passed away in hospital on 26 January 2020, aged 93. She was born in Didsbury in 1926 and attended Withington Girls’ School before following her mother (Hilda, née Broadbent) to Somerville in 1944 to read medicine.

At Somerville she made many lifelong friends, amongst them her first cousin Mary Ede (née Turner) and Ruth Lister. She travelled widely and often with the latter. Both survive her. In 1946 Leonora won her cricket blue.

After Oxford she returned to Manchester to complete her medical training where she was for five years Senior Medical Student, House Surgeon at the Manchester Royal Infirmary and House Physician at Crumpsall Hospital. Her first job reference in 1952 records: ‘I have the highest regard both for her practical ability and for her theoretical knowledge of medicine. Before coming to Manchester she graduated in Physiology at Oxford and this training has resulted in an intelligent and logical approach to medical problems. Dr Goulty has a pleasant personality and gets on well with patients and her medical colleagues. I have no hesitation in recommending her for any medical situation suitable for her seniority and experience.’

Leonora held posts at Westminster Children’s Hospital and Montreal Children’s Hospital before joining the Lowestoft general practice in 1958 where she remained until retirement in 1991. Her contract of employment contained a ‘no marriage’ clause but sadly she was destined never to test its enforceability. She was the GP of choice for Marks and

LEONORA GOULTY

Spencer and was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of General Practitioners in 1997. A well-known and popular figure in Lowestoft, she enjoyed being approached in later years by patients and thanked for delivering them and/or their relatives.

Leonora’s home in Lowestoft for over 60 years was a magnet for her many nephews, nieces, cousins, goddaughters and friends. To them all she was loyal, loving and generous with an encyclopaedic memory for all their activities which she expected everyone else to share. She was thrilled when her great-niece, Michelle Goulty, followed her down the welltrodden path from Withington GS to Somerville.

But no record of her life would be complete without reference to her frequent bouts of depression. Her former GP partner summed it up when he wrote: ‘I too have seen her many times thrown into the most dreadful despair, but to bounce back to excellent caring work in good cheer.’

Leonora’s wide interests included music, sport and travel. She rented a beach hut for decades and continued to swim in the sea well into her 80s even after new hips and knee operations. Her declining physical abilities eventually necessitated the support of a care home for her final years where she presented a challenge but the number of carers who attended her funeral bore witness to her being a challenge they relished. One said: ‘When she smiled she lit up the whole room’, and that is how she deserves to be remembered.

IAN GOULTY, nephew

At the end of Audrey Donnithorne’s requiem mass in Hong Kong on June 26, the congregation filed out to the strains of ‘Amazing Grace’ sung in Chinese, neatly encapsulating the two dominant themes of her life: deep attachment to China and its people, expressed throughout her career as a political economist, and her Catholic faith.

The only child of Protestant missionaries, she was born on 27 November 1922 in Anxian, a country town in Sichuan, China in 1922, where her parents had been sent by the Church Missionary Society. There she recalled being carried in a little sedan chair to go shopping with her mother and feeding mulberry leaves to silkworms that she kept in a drawer. Like other mission children she was sent to school in England (1927-40), first in Norfolk and then St Michael’s, Limpsfield in Surrey; holidays were spent with guardians or relatives unless her parents were on furlough. After School Certificate she rejoined them in Sichuan, relearning Mandarin and taking courses in Chinese history and anthropology at the West China Union University, a Protestant foundation in Chengdu. Spiritually, her dissatisfaction with the modernist direction of Protestant thinking was growing and she attended her first Catholic mass. She was eventually received into the Catholic Church in 1944.

In July 1943, following a perilous journey that took six months, including some weeks hospitalised in Agra with hepatitis, she landed in Liverpool and was conscripted into military intelligence in the War Office. By the time she went up to Somerville on a scholarship in October 1945, she was already 23 and, like returning servicemen, found it hard to adjust to the rarefied atmosphere of academia. In her autobiography, China in Life’s Foreground (2018), she comments on the psychological division between the post-war intake and those straight from school, for whom the undergraduate system was designed.

She settled down to read PPE despite being irked by aspects of the curriculum, especially economic theory, and suffering from the cold as electric fires were allowed only for two hours a day. The parts of university life she most enjoyed were the lasting friendships she made and the activities of the Catholic chaplaincy, though her lack of ballroom dancing skills put her at a disadvantage at its Saturday evening socials. She also joined the university Conservative Association, succeeding Margaret Roberts as college secretary.

Her degree proved to be her ‘rice bowl’ for life. On graduating she took a research assistant post in the department of political economy at University College London as a stop-gap, but stayed for twenty years, was made Reader in Chinese economic studies, co-wrote books on Western enterprise in the Far East with Professor GC Allen, and published her major work, China’s Economic System (1967). The latter entailed arduous field trips to China, where, besides researching agriculture, industry and finance, she sought out Chinese Catholics; she found Beijing’s policy towards religion at any one time was a useful measure of the general political atmosphere. The second half of her career, 1969-85, was spent at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra as a Professorial Fellow and first head of the Contemporary China Centre. The Cultural Revolution had just begun and put a stop to field trips for a number of years, during which time she converted part of her house to shelter Vietnamese refugees from communism. When her visits to China resumed in the 1980s, she planned a sequel to her earlier book, but had to abandon the project because the fast-changing economic system was ‘like an unset jelly’.

Culture wars were not confined to China: on the ANU campus she found herself at odds with radical feminists, especially over abortion, and a vocal critic of naive Maoist euphoria. Her decision to retire early to Hong Kong was inspired. From here she could visit the mainland regularly (until denied a visa) and work discreetly to aid surviving Catholics, for which the Holy See awarded her the Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice medal in 1993. Unmarried, she kept in touch assiduously with friends from all over the world, and her numerous relatives and godchildren.

PHILIPPA INGRAM, cousin

AUDREY DONNITHORNE

Rosalind Irene Bearcroft (Chamberlain, 1946)

Rosalind was born in Cardiff on 16 May 1926 and spent her formative years in the city. Although she had a lifelong love of animals, she decided at a young age that she wanted to be a doctor rather than a vet and so, after a successful school career, she studied Physiology, Anthropology and Anatomy at University College, Cardiff in 1943. In 1946 she came up to read Physiology at Somerville. She met her future husband,

ROSALIND BEARCROFT

Peter, who was at Balliol. Never one to pass up a challenge, Rosalind hitch-hiked to Rome on a college bursary, returning with more money than she set off with through the astute sale of black market coffee. After two years at Somerville, she continued her medical training at University College, London, gaining her MBBS in 1951. She and Peter were married in 1952.

Rosalind soon entered the rapidly developing field of psychiatry, becoming a consultant in 1966 and moving to Barming in Kent. When a local primary school was threatened with closure, Rosalind and Peter bought Barming Place, intending it to become both their family home and the new school site. Life at Barming Place was extraordinary. There were animals: dogs, cats, horses, goats, polecats, a tortoise, stick insects. There were concerts, weddings, and even a Plymouth Brethren church, which was given a temporary home by these two devout Catholics.

Over the years Rosalind kept in contact with a number of her friends from Somerville, most notably Audrey Donnithorne. Rosalind was an active member of a large number of groups, including the Catholic Union, the Association of Catholic Women, the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre, the Friends of the Holy Father, the Council of Christians and Jews, the St Augustine Society, the Catholic Medical Association, and many more besides. If anything, her contribution to these groups only increased as she grew older, as did the attention she gave to her many pet projects, including her longstanding attempts to obtain a dog for Pope Benedict XVI!

Rosalind’s energy was legendary, as was her generosity and kindness. She continued working into her late eighties and was awarded Catholic Woman of the Year in 2018. She always went the extra mile: taking on a primary school while also raising a family and being a consultant child psychiatrist was

AUDREY BUTLER

only the tip of the iceberg. Her dedication to family, faith and work was truly impressive. She will be greatly missed.

Roy Peachey, son-in-law

Audrey Butler (Clark, 1946)

Born in York in 1928, the elder sister of Gerald, Audrey spent most of her first five years in Düsseldorf, Weimar Germany, where her father worked for Price Waterhouse, and where she attended the local Kindergarten. When Hitler assumed power, the family returned to England (though this did not, apparently, prevent Audrey’s parents being added to the Nazis’ infamous ‘hanging list’, hastily compiled by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt prior to the planned 1940 invasion).

Back in England, Audrey’s schooling was peripatetic, following her father’s work to Bromley, Blundellsands (near Liverpool), Sutton Coalfield and Leeds, where she attended Allerton High between the ages of fourteen and eighteen. These moves, which inevitably broke up childhood friendships and entailed repeated new starts in established school classes, were emotionally disruptive. Always strong academically, Audrey excelled at Allerton, though initially she was often shunned by her classmates as an outsider with a soft, southern accent. Rather than moping, she channelled her spare-time energies into writing a young adult novel, The Vedor Sampler, which was accepted for publication in 1942, when she was fourteen. She had a short story read out on the BBC Children’s Hour and won several prizes in national poetry competitions. By the time she left Allerton, the initial turbulence was forgotten; in her final school exams she won two scholarships and left to read History at Somerville in October 1946.

Audrey loved her time at Oxford: the curriculum, the social life, the unique mix of demobbed servicemen taking war degrees and the ‘standard intake’. One of those ex-servicemen was Captain Arnold Butler whom she met at a medieval church history lecture. Shortly before that encounter, Audrey met Barbara Lockwood, another undergraduate, who had joined the same queue. (For what, is lost to history.) The two remained friends for more than seventy years and died within a few weeks of one another. As Barbara’s daughter, Liz, puts it: ‘Perhaps they are in the same heaven-bound queue, now!’ When Audrey made friendships (of which there were many), they lasted a lifetime.

Audrey and Arnold married in 1950. By now, she was working for Dents, a major publisher, where she became the editor of successive editions of Everyman’s Dictionary of Dates, edited the politics and history segments of a new encyclopaedia, translated for publication in English The Swiss Family Robinson and Noel and the Eagles from the original French, edited an anthology of English Prose and Poetry and wrote numerous forewords for classic works. While bringing up a family of five children, Audrey had two further novels published.

In retirement she enjoyed keeping local councillors on their toes as a part-time correspondent for the Lowestoft Journal. Together with Arnold she wrote a history of Somerleyton Brickfields and a guide to Suffolk’s historic churches, with the proceeds going to charity.

Audrey died on 12 May 2020. She is survived by her husband, Arnold, and three of her children, Francesca, Sophie and Patrick. Sadly, Mark and Guy pre-deceased her.

PATRICK BUTLER

Barbara Evelyn Forrai (Lockwood, 1946)

A multi-generational household including ex-teacher ‘aunts’ enhanced Barbara’s education, continuing through Blackheath High School GPDST (evacuated to Tunbridge Wells) and one-to-one lessons with an Oxford Mathematician who encouraged Barbara to go to Oxford, which she did assisted by a Ministry of Education means-tested grant and a Somerville Bursary, topped-up by paper rounds and holiday factory jobs. Rightly, ex-Service personnel had preference, so she felt extra-honoured to gain a place and cherished every moment and opportunity which Oxford gave her, never mind rationing and studying wrapped in a blanket. Throughout her life she endeavoured to put these achievements to good use.

Barbara’s mathematics teaching career in wide-ranging schools included: Argentina and Brazil where she married her beloved husband (died 1980), setting up a first computer department, coaching and telephone-tutoring until her death. Barbara spoke five languages, beginning Russian only when preparing for retirement, achieving in her seventies a degree which facilitated teaching Russian.

A superb family member and friend, Barbara had many interests – knitting, sewing, piano, singing, writing, reading, family history research, hosting foreign visitors, tennis into her nineties, skiing started in her fifties while accompanying school trips, and more. World War Two restrictions and her father’s dockland walks instilled ‘wanderlust’ and she became an intrepid traveller, visiting the Arctic, Antarctica, Asia, Americas, Australia and far areas of Russia, often including adventurous activities, most recently, aged 91, a hot air balloon.

Barbara’s life was one of service and long-term commitment to helping others – in particular, volunteering for the Oxford Society and the British Heart Foundation, serving as Chairman, Events Organiser and In Memoriam Secretary (continuing the last until her death), dealing with over £400,000 of donations with expertise in Gift Aid, also a month assisting a streetchildren charity in Chita, Siberia, which she was still supporting through Powerpoint presentations about her travels. Amongst other awards of appreciation, in 2017 she received the British Empire Medal (Civil Division), in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List, for services to charity in the UK and Russia.

We are thankful she led a full life until the end. Attitudes learnt in childhood meant she was always keen to learn, diligent about her studies and exercises, ready to participate, have a go or give help, while still thinking from others’ points of view and caring for those around her, all of which brought her cherished friends across the world. There was no funeral as it was her wish that her body be used for medical science, so even in death she continues her life-long passion for education, at the Cardiff School of Biosciences. We have every confidence that she will be remembered far and wide, for generations, but should anyone wish to commemorate her, she requested donations to the British Heart Foundation in her memory. Please include details for Gift Aid if you are eligible.

BARBARA FORRAI

VICTORIA WOTHERSPOON

Victoria Avril Jean Wotherspoon (Edwards, 1946)

Avril Edwards was the elder of two girls, born to a couple utterly devoted to each other. They grew up in Gosforth, and by all accounts Avril was a bit of a tomboy and keen on sport.

At the start of World War Two the family moved to Corbridge in Northumberland. Avril’s father joined the Admiralty in London to co-ordinate merchant shipping and she was sent away to school at Downe House. She hardly saw her father between the ages of 13 and 18, but at Downe she thrived academically, on the stage and on the sports field, ultimately becoming Head Girl and captain of tennis.

Avril went up to Somerville in 1946 to read English and she absolutely loved it. She achieved a half-blue at tennis and won her matches against Cambridge in successive years. One of her fellow students at Somerville was Barbara Harvey (subsequently Medieval History Tutor at Somerville) and the two became life-long friends. Another good friend was Elizabeth Graham (Lady Kirk), who remembers the three of them in a somewhat unholy alliance, all getting together round Barbara’s coal fire in Maitland when the 1947 power cuts switched off the central heating elsewhere.

After Oxford, Avril embarked on a teaching career and took up a post at St George’s, Ascot as an English teacher.

Her love-life was undoubtedly complicated, but at her sister Diana’s wedding she met the best man, Iain Wotherspoon, and they never looked back, marrying in 1952 and setting up home in the Highlands. They were blessed with 55 very happy years together and four children. When Avril’s father became Avril was ahead of her time. She smoked a mean cigar, never went to the hill without a flask of whisky and wasn’t shy to stalk or shoot with the best of them. She swam in the lochs and fished her way up and down the country. She knew the names of all the wild flowers; and then it was time to put on the ballgown, the heels, the lipstick and join in the dancing.

Her golf was impressive. She had a single figure handicap and represented the north of Scotland for many years. She also threw herself into sharing the other love of Iain’s life, a 45ft wooden Buckie-built fishing boat, which every year the family took down the Great Glen through the Caledonian Canal to cruise the west coast.

Having a strong sense of public duty she immersed herself in the Children’s Hearing Panel after her own children were grown up. She served on the Panel for fourteen years, many of them as Chairman for the Highland Region.

Avril was a devoted wife and mother to whom family meant everything, but she was no cook – she was not interested. Her family were possibly lucky to have survived some of her efforts. She was able to spend her final days at home. Her sense of humour never dimmed. Throughout her life she had a marvellous time.

JONNY WOTHERSPOON, son

Chrystal Heather Ashton (Champion, 1947)

When Heather Champion first arrived at Somerville at the start of Michaelmas term 1947 she had recently returned from six years as a child evacuee in Pennsylvania. The transition from land of plenty to post-war austerity cannot have been easy. In Oxford, food, fuel, books and clothes were all in short supply.

But in those years of renewal, anything must have seemed possible. She wanted to be a doctor, and she had come to the right place. Oxford was already her new home. Her father, Sir Harry Champion, was Professor of Forestry, her elder brother Jimmy an undergraduate at New College, and the family lived on Boars Hill.

She excelled at her studies. She played squash for the university. She fell in love, with John Ashton, lately a naval airman and now reading agricultural economics at Brasenose. Soon after she graduated in 1951 with first class honours in physiology, they married at Sunningwell.

Heather was born on 11 July 1929 in Dehradun, India (where her father was then Silviculturist at the Forest Research Institute). Thanks to her Indian ayah, she spoke Hindi before English. If the sun shone over her first six years, the next five, boarding far from home at Oldfield School in Swanage, left mixed memories. She just survived the evacuation convoy to New York in 1940, watching as a U-boat torpedo narrowly missed her ship, and looked back on her American adolescence

After Oxford she and John moved to London. She finished clinical training at the Middlesex Hospital, qualifying in 1954. She stayed at the Middlesex as a junior doctor. Drawn increasingly towards research, she published early papers on cardiology and blood circulation.

In 1965 she moved to Newcastle, on John’s recruitment to set up a new Department of Agricultural Economics. Here, as researcher, clinician and teacher for over half a century, she made a home, raised a family of four and established herself among the leading clinical pharmacologists of her generation.

Working from the Department of Pharmacology and at the Royal Victoria Infirmary, initially with her friend and mentor John Thompson, she did significant work on pain management, nicotine, and cannabis. She was among the first to use electroencephalography to investigate changes in neural activity. She saw teaching as a privilege not a chore, and became a popular lecturer in the Medical School.

Her later work, on benzodiazepine tranquilizers, touched countless lives. She was among the first to reveal the dangers of dependency on these potent drugs. In 1982 she established the world’s only dedicated clinic for benzodiazepine withdrawal.

There she showed that most people could withdraw safely, and devised the only reliable protocol for doing so. She could have profited from it, but made her method freely available online. For patients and clinicians alike, the ‘Ashton Manual’ soon became an indispensable resource (now in eleven languages: www.benzo.org).

She left her mark with her character as much as her accomplishments.

She treated her patients as people not symptoms; saw no contradiction between compassion and objectivity; and turned nobody away who sought her help. She was guided by curiosity and rigour, not convention or the approval of peers. She was passionate about the integrity of her calling, never accepted industry funding, and was proud to be among the founding generation of NHS clinicians.

She saw the career ladder as a distraction; but was gratified in 1975 when elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, and by the later award of a personal Chair in Clinical Psychopharmacology. In 1994 she made her final move, to the Department of Psychiatry. Long beyond her formal retirement and well into her eighties she continued, mostly unremunerated, to teach, publish, advise patients and contribute to dependency support activities, including for twenty years as Vice-Chair of the North East Council on Addictions (NECA).

She was always grateful to Oxford and Somerville, especially to Janet Vaughan and Dorothy Hodgkin for their wise tutelage. She cherished her many Somerville friends, including Ros Maskell (Rewcastle), and Jean Hunter (Hopkins).

John died in 1986. Heather threw herself into her work, but missed him constantly, as she did the beloved family dog, Rex. She died peacefully at home after a long illness, aged 90, on 15 September 2019. She is herself missed by her children John, Caroline, Jim and Andrew; six grandchildren; numerous friends from all walks of life especially in the north-east; and generations of patients, colleagues, and students.

JOHN ASHTON, son

CHRYSTAL ASHTON

Antonia Gransden (Morland, 1947)

Antonia Gransden died on 18 January 2020 in Keinton Mandeville, Somerset, aged 91. As historian James Clark wrote in the obituary that appeared in the Guardian on 16 February 2020, she ‘was among the foremost medievalists of her generation. Her substantial and sustained scholarship spanned seven decades and continues to guide today’s students and researchers.’ A further obituary appeared in the Readers’ Lives section of the Times on 14 March 2020.

Antonia was born in 1928 in Compton Dundon, Somerset, as the second daughter of Stephen Coleby Morland, Quaker manufacturer, local politician and historian, and Hilda Street. She was educated at Dartington Hall, Devon, and Badminton School, Bristol, before winning a scholarship to Somerville, where her mother had been before her. Antonia gained First Class Honours in Modern History in 1951. She subsequently gained a PhD, and was awarded a DLitt (Oxon.) for outstanding academic achievements in 1984.

Her most substantial publications were the two-volume Historical Writing in England (1974, 1982), which covers the period from circa 550 to the early sixteenth century, and the two-volume History of the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds, covering the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries. Her work

ANTONIA GRANSDEN

on Bury St Edmunds had begun during her years as Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum (1952–1962) and she completed it at the age of 86. She also wrote many articles and reviews.

In 1965 she was appointed to a lectureship at Nottingham University, retiring as reader in 1989. In retirement she moved first to Cambridge, then to Oxford, and finally to her home county of Somerset.

Even in retirement, Antonia continued to work to a strict schedule, and did not care to be disturbed. Morning disturbances were particularly unwelcome. Over lunch she often read nineteenth-century novels; Walter Scott and Wilkie Collins were favourites. On Sundays she walked, and these walks were sometimes connected with her work. During the Cambridge years she spent many hours walking along East Anglian towpaths, investigating sites and remains of monastic mills.

Single-minded as she was about her work, she also enjoyed social contacts and dinner parties, often with fellow historians. In Cambridge she appreciated the scholarly conviviality of Clare Hall, and during her latter years in Oxford she was glad to re-establish contacts with Somerville. She liked to hitch up her skirts and cycle across the Parks to college guest nights.

Although not given to conventional domesticity, Antonia was deeply attached to her immediate family. She took an active interest in the personal and working lives of her children and grandchildren, and participated fully in family celebrations, and in everyday household and culinary life, whenever the opportunity arose. Having shown an early gift for painting, and created a collection of nature diaries illustrated with watercolours of wildlife, she was able to pass on a wealth of traditional lore. Her interest in art led her to become a connoisseur and collector, especially of early modern European paintings, which she studied with forensic attention to detail, and provenance. She enjoyed cultural tours to Europe and to far-flung destinations, often accompanied by one or more of her grandchildren.

A prolific writer, Antonia was never at ease with a keyboard. All her work was written by hand, with bibliographical references on index cards, and footnotes on little slips of paper. Resistance to electronic information retrieval was perhaps the key to astonishing feats of memory. Even in the last months of her life she was able to indicate the location of items she required from dense sheaves of paper on the various surfaces around her room.

She resisted the onset of osteoporosis with a regime of cold baths, exercise and healthy eating. But a series of grave falls and fractures led to periods of hospitalisation, and, when she could no longer walk, to residential care, where her family continued to support her. She preferred being read to, rather than learning to press the right buttons on her audiobook player.

Antonia married three times. Her second husband, the literary scholar, poet and critic KW (Ken) Gransden, whom she married in 1956, died in 1998. She is survived by their two children, Katherine and Deborah, seven grandchildren and three greatgrandchildren.

CHARITY SCOTT STOKES (1957)

Vivienne Blackburn (1952)

For Vivienne, Somerville was the start of a life-long adventure. It opened doors to a world of study, culture, and travel of which she could only have dreamed in her early years, living in the narrow confines of a small mining town in the north-east of England.

Her work for three months as an au pair for a cultured and forward-looking French family in Bordeaux began a passionate relationship with France which saw her developing an extensive knowledge of its people, its country and its language, and which also gave her a taste for travel.

From Somerville, she gained a love of academic study, research and discourse which underpinned her whole life. She would always pay tribute to the support, guidance and ongoing encouragement provided by her college tutor, Mrs Olive Sayce, with whom she maintained contact until her death in 2013. Her interest in the arts also dates from this time. She became a keen amateur cellist and listener, a regular visitor to art galleries at home and abroad, an avid theatre-goer and a prolific reader of classical and contemporary novels in both English and French.

Following a PGCE at Newcastle University and nine years as a teacher, she moved to Stockwell College, Bromley. This placed her at the forefront of the development of teacher training, initially to a three-year diploma and ultimately to BEd degree level. Always academically engaged, she completed a London MPhil in French Literature on Paul Eluard and was appointed a

VIVIENNE BLACKBURN

lecturer of the University. When the College closed, she joined the ranks of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Schools, a move which necessitated her relocation to Yorkshire.

HMI colleagues paint a generous picture of Vivienne – highly professional, quietly efficient, courteous and kind, perceptive and sound in judgement, and at the same time with a lively sense of humour, a quick wit, and an eye for the ridiculous. In 1985 she was seconded to the European Community in Brussels, charged with preparing a report with a French colleague, drawing on practice in the twelve countries they visited, and suggesting common objectives for professional teacher training.

Retirement in 1990 brought with it the opportunity for Vivienne to return to the academic life. She enrolled at Leeds University, not in modern languages but in theology. Following an MA she went on to take a PhD on the work of Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Simone Weil, and to write a book – Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Simone Weil: A Study in Christian Responsiveness – whilst also becoming a regular contributor to theological journals and to the local Café Humanité.

Family ties were always important for Vivienne. When her mother died during her last year at Oxford, she took on the care of her thirteen-year-old sister forming a lifetime bond between them. She was a devoted aunt to her nephews and they and their families gladly supported her in recent years when physical and mental difficulties began to restrict her lifestyle. She is survived by her sister Marjorie and her nephews, David and Jonathan.

MARJORIE AYLING, sister

LADY HOWARD

Lady Jane Mary Howard (Waldegrave, 1952)

In 1934 Jinny Waldegrave had the good fortune to be born into an aristocratic family that most unusually valued education for daughters as highly as for sons. Her mother, Mary Waldegrave (née Grenfell) went up to Somerville as a scholar in the 1920s, Jinny went up as an exhibitioner in the 1950s and was followed by a daughter in the 1970s. As her mother had done, however, she left after only one year to get married and the next twenty-three years of her life was dominated by rearing her six children and life as a chatelaine, entertaining on a large scale, running the Bath Festival for six years with her husband and supporting his nascent political career in the 1970s. Then the marriage broke down, she remarried a Scottish airline pilot and for three years lived an entirely different life. This marriage also failed and she found herself in her mid-forties with very little money and no qualifications for earning a living. Nothing daunted, she trained as Blue Badge Guide in London, escorting tourists around the sights of London, and gradually established herself as a tour guide with her own business, specialising in taking small parties of American tourists on exclusive visits to Great British houses and gardens, many of whom returned to tour with her year after year and became personal friends. Aged 70, she retired to live in Cambridge, where various of her seventeen grandchildren appeared at the university over the years. Once more she reinvented herself and made new friends, rejoicing particularly in the rich offerings of classical and ecclesiastical music that Cambridge afforded. Her last decade was one of increasing ill health and debility, born without complaint.

She was a woman of extraordinary energy and charm and almost boundless self-confidence. Her most remarkable achievement was probably her rescue, almost single-handed, of the teenage son of an old friend who had ended up in a Turkish prison after becoming involved with drugs. Then in her midthirties, knowing no-one in Turkey and armed only with crates of whisky for bribes (supplied by a sympathetic brother-in-law, John Dewar), she set off for Istanbul and duly returned with the young man a month or so later. Not usually given to modesty, she never spoke much about how she had accomplished this, but she undoubtedly risked her own life and liberty.

If she had been born fifty years earlier, she might have been a great political hostess; fifty years later, she would likely have completed her education and combined her domestic responsibilities – in which she was never much interested – with a high-flying professional career. As it was, she never quite found equilibrium in her life, but never gave up trying.

JANE MORRIS-JONES (1973), daughter

Clare Eaglestone (Goodall, 1953)

Clare was born in Liverpool in 1934. Educated at St LeonardsMayfield School, where she was Head Girl, she was delighted to come up to Somerville in 1953. She often told the story of how she met Gina Alexander (Pirani) by chance at Oxford Station and shared a taxi with her to Somerville, where she was terribly impressed with Gina’s inquiry about whether any post had arrived for her. She frequently talked about her tutors, especially Agatha Ramm, and described the feeling of her ‘head expanding’ in tutorials: Clare maintained an interest in history all her life. After leaving Oxford, she worked for Time and Tide magazine. In 1959, she married Alex Eaglestone, a graduate of Magdalen and then a Naval Officer. At the end of his commission, they moved to the Middle East: Alex worked for the British Council and Clare as an English teacher. They had two daughters, Catherine (1960; Somerville, 1978) and Elizabeth (1962). They then moved to Brazil, returning to the UK in 1966; Alex had taken a post at the Royal Naval College in Greenwich. Clare taught at St Theresa’s, a Catholic Secondary Comprehensive in Lewisham. Three more children followed: Robert (1968), Margaret (1971) and William (1972). In 1979, Clare had a Teacher’s Sabbatical at Somerville, during which she deepened her knowledge of the Romans’ settlement of Britain, and in 1981 the family moved back to Oxford. Clare worked at Balliol College as the Secretary of the College Society, a job she greatly enjoyed. Retiring by parts over the 1990s, Clare was a founder and regular volunteer at the Gatehouse, a charity providing food and shelter for the homeless in Oxford. A devout Catholic all her life, Clare was also continuously involved with a number of Church activities. The house in Oxford was always full of people, often priests and religious who had recently moved to the city for sabbaticals or work, to whom Alex and Clare offered generous and animated hospitality. Alex died in 2007. At around the same time, Clare began to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease and moved to Vale House, a specialised home in Littlemore. She had fourteen grandchildren. She died peacefully 6 August 2020. Going up to Oxford after a rather frightening and difficult wartime childhood in Liverpool was a great moment in her life, and she was always grateful for the opportunities Somerville gave her and even more for the friendships she made there.

ROBERT EAGLESTONE and GINA ALEXANDER

CLARE EAGLESTONE

Robert adds: My mother absolutely loved Somerville: it had a huge impact on her life and she was really proud of the college. When I was a little boy, because of the way she talked about it, it seemed to me like a fairy-tale place, like Camelot, and has never really lost that kind of sheen for me!

Anne Penelope (Penny) Iles, formerly Lowde, (Hornblower, 1954)

Penny was born on 20 December 1935 and educated at Cheltenham Ladies’ College. She came up to Somerville in 1954 to read Physics and was forever fondly committed to the college.

Soon after graduation she was offered a happy position working on carbon-dating finds for the University Museum. From there she moved to work at Oxford Instruments and then Harwell. Here she met and married Dr. Raymond Douglas Lowde, a theoretical physicist. From this marriage she had three children, Felicity, Justin and Corydon. Being a mother took precedence and she left her career, although when the children were older she took a job teaching Mathematics at Cokethorpe School.

PENNY ILES

After a divorce in 1982, Penny met Dudley Iles. Both Dudley and Penny retired from teaching at the end of the 1980s and two decades of adventure and service followed, with special highlights being sixteen tours on various cruise ships around the world, mostly with Dudley lecturing on birds (about which he was a world expert) with Penny providing invaluable administrative support.

Driven to have a greater impact for the good of those less fortunate, Penny and Dudley undertook a two year service in Zanzibar off the coast of Tanzania with VSO, an organisation for which they had a great affection. It is of some note that Penny was the first and only grandmother VSO had ever had on their motorbike training course and she adored speeding about the island. Both she and Dudley were grateful to the African mindset for their respect of education in general and the way that they respected also the experience of their elders.

Penny’s service included her dedication to the Citizens Advice Bureau, where she worked for two decades regularly as a volunteer, using her significant abilities at research and investigation (in the days long before the internet) to champion the plight of those at the mercy of the system.

Penny was committed to the local community. She was heavily involved in local campaigns, and numerous societies. More broadly, she was a member of several arts societies and countryside charities, and often would take delight in visiting Kew Gardens, Wisley and many glorious National Trust properties. Gardening was a passion and she continued to maintain a beautiful garden at home. She also had a passion for Bridge and played to a good standard for many years at various clubs and events.

Penny was progressively afflicted with severe hearing loss from the 1980s onwards and bore the inevitable frustrations associated with deafness with stoicism and courage. Just days before she passed away, she discovered the brilliant book Sound by Bella Bathurst and she described it as the only account that had ever been able to capture the many varied feelings of isolation that accompany hearing loss.

Penny was devoted to her family, and will be greatly missed by her three children, two step-children, four siblings, and beloved grandchildren.

CORYDON LOWDE, son

CAROLINE KENNY

Caroline Anne Florence Kenny (Arthur, 1956)

When Caroline looked back at her Somerville years, she recalled much music, the pleasure of delving into the past and learning how to construct an argument, Port Meadow and the Oxford countryside. But her sharpest memory was of Sputnik going over in 1957 – evidence of her wide horizons. Descended from Colonial Office Arthurs on her father’s side and Foreign Office Spring-Rices on her mother’s, she was certainly well-travelled by the time she reached Oxford. Born in London in 1937, she had spent her infancy in Cyprus, escaped to South Africa in the war with her beloved Spring-Rice grandmother and younger brother Tom, and then made a highly dangerous journey back

While she was at Somerville her father was appointed Governor of the Bahamas. She spent her summers there with her parents, reappearing with amusing stories and Fats Waller records. Her family base in London was the roomy house known as the Ricery (from the Spring-Rice family), with open door for her friends.

After graduating, Caroline spent a memorable year in the Bahamas and then five years at Glyndebourne, working front of house. There she met the musician Courtney Kenny, who was on the music staff, and they married in 1972. Their house in London was a busy centre of music teaching and performance – keyboard and voice. After training at Goldsmiths Caroline taught music with great enjoyment and success at Michael Faraday School in South London. As an imaginative, kind, and yet formidable person she knew how to bring out the best in the children, putting on shows, taking them to concerts, and even on camping trips.

The birth of her son Francis transformed her life, and from then on her special qualities were needed at home. After a year in Ireland looking after Courtney’s mother, the Kennys moved to Sussex, to the top floor of the family house at Burwash occupied by Caroline’s brother. After thirteen years there Caroline, Courtney and Francis (always a trio) bought their own house, further along the beautiful sunny valley. They finally had central heating, and a sweep of fruit, vegetables and flowers – Caroline, like her father, was a dedicated gardener.

Caroline and Courtney filled their house with books and music. They had an unusually wide circle of cousins and friends, and all were welcome for delicious meals, conviviality, and laughter. They were also, with Francis, key figures in local Sussex life, at Etchingham church, at Christmas plays, at village suppers, at concerts and choir rehearsals in their house.

Caroline was often on the move – to visit family in Scotland and Ireland, to the Mediterranean, and North America. Even after Courtney became dependent on a wheelchair the indomitable trio managed to travel as energetically as ever, up and down to London by train, to Ohio and Wexford for opera festivals (anything but Wagner for Caroline) and always to Glyndebourne. There was one last trip for Caroline, when she was invited to Ottawa to give the address at the opening of the memorial to her very distinguished grandfather Cecil Spring-Rice, ambassador and poet. He is now best known as the author of ‘I Vow to Thee My Country’, and Caroline had been kept very busy correcting fanciful theories about its meaning.

Caroline, asthmatic from childhood, eventually developed emphysema. It took her in and out of hospital for the last couple of years before she died, lucid to the end. Her funeral was held in the fascinatingly historic Etchingham church: ancient, freezing cold, and bright with December sunshine. Just as she would have wished, it was crammed with family and friends.

FRANCES WALSH (1956)

JANET TRELOAR

Janet Quintrell Treloar (1958)

Somerville played a very large part in the life of Janet Treloar, starting with Dame Janet Vaughan and concluding with another Janet, Baroness Royall.

Janet came up in 1958. She was naturally gifted with abilities to see and describe geopolitical situations and was awarded a place on the strength of her essay about the Eighth Army in the Rhineland. Arriving in Oxford she reignited a relationship, begun in Cornwall, with a geology undergraduate at Corpus Christi college, Richard Hardman.

Early in 1960, mid-way through her second year reading geography, she became pregnant. This meant being sent down for breaching the rules. Janet plucked up her courage to see Dame Janet Vaughan (Principal 1945–1967). This was a lifechanging moment; she could keep the child on condition no one must know. Tamsyn was born in October and two weeks later Janet commenced her final year at Oxford.

Janet was an artist and was blessed with being a brilliant draughtswoman and colourist. It is no exaggeration to say that there was not a day that went by that she hadn’t drawn or painted at least once. Her favourite medium became watercolours and she pushed that medium as far as she could. Many years after leaving Oxford she was invited to Russia to visit the site of the battle for Stalingrad in 1944. She was hugely moved by the sacrifices that Russian people had made to resist the Nazi threat. When she got to Stalingrad (now Volgograd) she went down on her knees and dropped her entire watercolour pad into the River Volga. She grabbed soil from the

bank and rubbed it over the surface of the sheet of paper. This was in freezing temperatures and very soon the water turned to ice.

After Oxford, Janet’s expatriate married life took her to Libya, Kuwait, and Colombia in the 1960s and Norway (1970s). She immersed herself into these countries’ cultures, something that had a profound and lasting effect. After four children and happy years raising her family, Janet returned to her academic roots. Remembering a trip to France from her early twenties, she started a series of paintings based on the Romanesque arch. This project took some fifteen years, taking her across Europe from Croatia to Spain and Provence to Norway. Her project title ‘A common language for Europe’ carried the wish for an understanding that the political ties of Europe were already underpinned by our common European heritage through the Romanesque arch.

Her next theme was suggested by a former US journalist who had been based in Moscow: Russia’s ‘Hero Cities’. This started a series of paintings around the Russian sacrifice during what Russians call the ‘Great Patriotic War’, in which 26 million Russian people died. Her geopolitical antennae still at work, she was received by the Russian Ambassador with open arms and with an invitation to exhibit at the Russian Embassy in London. The evening was a great success for Anglo-Russian friendship and for remembering the great solidarity between Britain and Russia at the time of crisis in the Second World War. Further exhibitions followed and culminated in an award from President Putin of the Russian Honorary Silver Order for services to Anglo-Russia relations.

Her Russian work developed into an interest in Anna Akhmatova, widely regarded as the heart of Russia’s poetic soul. Janet was invited to be artist-in-residence at the Anna Akhmatova Memorial Museum, St Petersburg, followed by an exhibition at Pushkin House, London. Through this interest she made the connexion to Isaiah Berlin. He and Akhmatova met and established a mutual respect and admiration. In 1965 Akhmatova paid a visit to Oxford and met Berlin for the final time. Akhmatova’s remark, ‘I see my bird lives in a gilded cage’ made apropos Berlin’s life at All Souls, is what Janet interpreted as the pivotal spur for Berlin becoming the founding President of Wolfson College in 1966, with all the risk that that entailed. And so our circle is nearly complete, because alongside Berlin as one of the three inaugural trustees of Wolfson College was Dame Janet Vaughan.

When the opportunity came for Janet to meet Baroness Royall there was an instant meeting of minds, and for Janet, at what turned out to be the end of her life, a wonderful recognition from the Principal, and college, that her life, which had begun in such difficult circumstances but with kindness and tolerance, had received the recognition that she had always hoped for.

On 10 June 2018 Janet exhibited at Wolfson College with ‘An Exhibition of Paintings of Fountain House, St Petersburg – where Anna Akhmatova was living when she met Isiah Berlin in 1945’. The exhibition was opened by Baroness Royall. Janet donated a sum of money to Somerville to create the Janet Treloar Anna Akhmatova Travel Grant for undergraduates. One of Janet’s pictures is featured in Somerville’s anniversary book Somerville 140. Janet was elected a Fellow of the Royal Watercolour Society and served as Vice-President.

She is survived by her husband John Hale-White and her four children, Tamsyn, Paul, Alice and Arthur.

PAUL HARDMAN, son

A PAINTING BY JANET TRELOAR

Reproductions of Janet’s watercolours can be found in the online Commemoration booklet on the College website.

Elizabeth Patricia Goulding (1960)

Elizabeth loved poetry and literature. She believed that language provides the liaison of minds across time.

She was born in New Zealand in 1938. Her mother Nona was a hospital almoner. Her father Arthur, a magistrate, had won a Military Cross in World War I. Elizabeth was Head Girl at Chilton Saint James School, from which she won a prestigious National Scholarship enabling her to study for an arts degree at Victoria University. There she won scholarships to study at Oxford. Air travel being a rarity in 1960, Elizabeth enjoyed the monthlong voyage from New Zealand via the Panama Canal to the UK on the ship Rangitane with other postgraduate students travelling to universities in Europe. In London her godmother Amy Kane introduced her to the joys of live theatre.

Oxford was a bit of a shock. At first Elizabeth was lonely, feeling overwhelmed by the mix of talented students with different ideas, aspirations and educational backgrounds. However, she lived in college and as she settled down to

ELIZABETH GOULDING

study hard she made many lifelong friends. She enjoyed theatre, debates at the Oxford Union and riding at the Oxford Horsemanship Club. She learned to punt. At Somerville Dame Janet Vaughan and Dr Enid Starkie, who tutored her in French studies, proved inspirational. Elizabeth was thrilled to spend time in Paris staying with the de Praingy family, contacts she maintained for life. Her parents and sister came to the UK and the family travelled together extensively.

She worked in London as a translator at Shell but was recruited to teach at Otago University where she became Head of the Department of French Language and Literature. Her achievements there were recognised by the French Government which made her a Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Palmes Académiques in 1992.

Elizabeth studied for her French doctorate under the direction of the eminent scholar Professor Jacques Body, Président de l’université de Tours. Jean-Pierre Giraudoux, the son of Jean Giraudoux, attended Elizabeth’s successful defence of her thesis on ‘Le “Motif” de la Communication dans les premiers ouvrages et dans les romans de Jean Giraudoux’. Elizabeth was an editor of the Gallimard Pléiade edition of Combat avec l’ange. She was a member of the Société Internationale des Études Giralduciennes (SIEG), publishing papers from conferences in Tours, Bursa, Cusset, Montreal, Aleppo, ParisSorbonne, Fez and Madrid. In retirement she contributed to the Dictionnaire Jean Giraudoux, followed tennis and was a keen fan of Roger Federer.

In August 2019 Elizabeth was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. A strange thing happened the day before she died. Her beautiful Yorkshire Terrier Dexa died unexpectedly. Her sister was shocked to find him dead on the doorstep having left him playing happily in the garden only two hours earlier. Although Elizabeth never knew of this, it seems fitting such close companions were linked in death. As Jacques Body recently suggested, Giraudoux would surely have turned this into a short story in La France Sentimentale.

AILSA GOULDING, sister, and SONIA SPURDLE (1961)

NINA CARTWRIGHT

Nina Valerie Cartwright (Bearman, 1961)

Nina was born in Lambeth on 7 August 1937 to Lilian, a graduate of the Slade School of Fine Art, and Edward Bearman, a boat-builder. During the Second World War Nina was evacuated from Chelsea to Oxford and the West Country, and then, after thriving at boarding school and the Lycée de Londres, Nina completed her Advanced level GCSEs at the then Westminster College of Commerce.

A powerful influence on her childhood was her ‘Uncle E’ (Ernest Kenton), who took Nina on an eventful tour of France. As a child Nina developed a love of the French language, foreign travel and sunny climes that never left her.

Nina was an energetic and vibrant woman who threw herself into whatever she did with commitment. She took up ice skating as a child in London and became a professional ice dancer, touring India and Japan in 1958-59 with Holiday on Ice. It was while on tour in New Delhi that she met her husband Michael, whom she married in 1962. They moved to Park Town, Oxford and then six months after the birth of their first

child Christopher to 1 Winchester Road, which remains their family home. Never one to rest, Nina simultaneously completed her medical studies and her family with sons Giles and Nick.

Nina studied for her first degree in medicine at UCL from 1961, completing her MBBS in 1966 at Somerville. After working as a house officer at the then Cowley Road Hospital, she went on to become a GP at the Wolvercote surgery, where she was the local doctor for thirty years until her retirement in 2002, and where she is still remembered fondly.

Nina was a prolific and enthusiastic gardener and won several ‘Oxford in Bloom’ prizes at her surgery. In spite of a busy family and demanding professional life, she still found time to pursue her interests in languages and in sport, playing club badminton and tennis competitively, as well as ice dancing, a life-long passion; she was a stalwart member of the Oxford Ice Dance Club and won a steady stream of medals. For a few weeks each summer in the early 1970s Nina even found time for It’s a Knockout, initially representing Bicester locally and then Great Britain in Italy in 1973.

At home Nina was a loving wife and mother and a generous and welcoming host. She lived her whole life with unrelenting enthusiasm and joie de vivre and is greatly missed by all her friends and family.

CHRISTOPHER CARTWRIGHT

Gaby Charing (1962)

Gaby was born on 6 May 1944 and went to King Alfred’s School in North London. Her parents wanted an educational environment for their bright, independent daughter that would give her a better experience than her father had as a Jewish boy in a grammar school. Gaby went up to Somerville to read PPE. She was awarded an exhibition but felt that she had missed out on a scholarship because she made a joke at her interview which was met with disapproval. Being gay in the 1960s was hard; there was little pastoral support and Gaby suffered. She always remembered Philippa Foot with great affection and spoke at her Somerville memorial.

Gaby went to SOAS to study Linguistics and worked in publishing and at NCCL as a caseworker. She trained as a solicitor and went on to specialise in childcare, employment and discrimination law. Her final job was as a policy advisor at the Law Society.

Gaby was a woman not just of passionately held and articulately expressed views, but of action, in a myriad of contexts, for the communal good. A member of the Gay Liberation Front in the UK in the 1970s, her support of a variety of LGBTQ causes was a constant through her life. She met and inspired many people along the way, and her work championing the pursuit of a more fair and equal society has played a large part in the progress that our community has made to date. speak out for inclusion and against discrimination and prejudice. Gaby joked that she would like to be remembered as someone ‘noted for the sweetness of her disposition’, but described herself, probably more accurately, in her Twitter profile as ‘opinionated, funny, kind and grumpy’.

Gaby was always interested in people and sought out that personal connection. In the long hours of the night when she was an inpatient, Gaby would ask staff about their training and their families. She always remembered their names and the names of their children. It was part of her fascination with what drives and motivates people. And people remembered her and often commented on the strength of our relationship.

We have two adoptive daughters – women who have invited us into a parental role in their lives: Gracey Morgan and Claire Berlinski, and Gaby was immensely proud of both of them. Claire remembers Gaby as ‘a lion. Her mind remained razorsharp until the end. She never succumbed to self-pity. She faced death with an extraordinary dignity. She wished, I know, to be remembered for that, and I will never forget it. She was truly strong. Just plain courageous.’ Gaby always described her mother as someone with great strength and fortitude, but it wasn’t until her own illness that Gaby came to understand how strong and resilient she herself was, and it was a surprise and a comfort to her.

Gaby loved to talk. She had an insatiable interest in so many things and read all the time. At St Christopher’s Hospice they ask patients to fill in a short profile so staff can see what is important to them; Gaby’s comments:

GABY CHARING

‘How to support me: shut me up! listen to me! I know the combination is hard!’

… and the world will be a quieter and less vibrant place now she is gone.

Gaby died aged 76 at St Christopher’s, after living for seven years with rectal cancer. We prepared for this day by writing a paper together: Day, Elizabeth and Charing, Gaby (2018) ‘Living with Dying and Bereavement’, Murmurations 1(2), 2739 https://doi.org/10.28963/1.2.4

LIZ DAY, partner

Mary Ann Poulter (Smallbone, 1965)

Ann was born on 2 February 1946 in Harpenden, Hertfordshire. The only child of a widowed mother, her friends at the time felt that she had a rather solitary childhood but nevertheless had a loving and supportive extended family.

Ann had her schooling at St Albans High School and later at Cheltenham Ladies’ College. From there she won an exhibition to Somerville to read Modern Languages and came up to read Italian in 1965. She had been a musician throughout her school days and would like to have read music but was persuaded that Modern Languages offered better career prospects. After a brief stint in Perugia in Italy and in Switzerland with relatives, she came up to Oxford where she made many life-long friends. Until recently, Ann would meet for lunch once a year with her contemporary Modern Languages students from Somerville.

On going down from Oxford, Ann signed up for a graduate traineeship with the National Coal Board. There she acquired varied experience, including going down a mine. While at the Coal Board, she developed an interest in housing law, and after a few years decided to follow a career in the law. She then decided to qualify as a solicitor at her own expense and joined a City firm as a trainee where she met her future husband Alan. Having decided to get married, Ann and Alan looked for posts outside London and decided on Oxford when Alan was offered a job there. Ann subsequently took a job in another local firm and they moved to Oxford in 1974.

Ann and Alan had five children who all grew up in their home in South Oxford. The demands of motherhood meant that Ann had to give up her job in the law but she later joined the University Disability Office as a Disability Adviser and found real satisfaction in that role until her retirement.

Despite her other responsibilities, Ann was a tireless charityworker and gave much time and effort to the Gatehouse, a charity for homeless people in Oxford, and was instrumental in getting the Oxford Food Bank (of which she later served as a trustee) off the ground. She also made a huge contribution to the South Oxford Adventure Playground, a highly successful play-scheme enjoyed by children from all over the city. Other charities which she supported by active participation in their work were Christians Against Poverty and Asylum Welcome. Always active in the community, Ann helped to form the first parent-teacher association at her children’s school and for many years took part in the organisation of the Oxford Music Festival. Throughout her time in South Oxford, Ann was a devoted member of St Matthew’s church.

In the final weeks of her life, Ann suffered from secondary breast cancer and she died of a heart attack on 26 March 2020. She led a full and active life and will be greatly missed by her family and many friends.

ALAN POULTER

MARY ANN POULTER

Judith Gray (1970)

Judith Gray sadly died on 3 June 2020 in France. Tragically a fire broke out in her kitchen, and despite being rescued by two brave young French men, she died from the effects of smoke inhalation, having had COPD for many years.

Judith was born on 7 May 1952 in Manchester, the youngest of five children. As a young child she was very sociable, loved visiting friends, and having them round to tea.

Her family moved to Woking, but sadly her father, a GP, was killed in a road accident when she was ten years old. He eldest sister Rosemary became her mother figure to whom she was very close. Despite this trauma, she focused on her schooling, being bright and intelligent, passing her 11-plus to attend Woking Grammar School. She was encouraged to apply for Oxford and achieved a place to read History at Somerville in 1970.

She was unsure what to expect but soon developed a longlasting friendship and links with those in her tutorials, Christabel Shawcross, Elizabeth Black and Elizabeth Clough. All moved out to share a flat in their second year. Life was lived to the full; even more so with the arrival of Judith’s guitar-playing brother Nick, for a few days which turned into a year. She studied and played hard, but did find the discipline of an Agatha Ramm tutorial somewhat challenging to her free spirit, always losing debates over unmoveable deadlines! She achieved a second class degree in Modern History.

She then trained to be a social worker in the London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, gaining a certificate of Social Work from London University. Three years later, she moved to Leeds, where she married. She much enjoyed social work, working with families and adolescents, but found the increasing bureaucratisation of social services too stifling; with the breakdown of her marriage she decided on a life change, moving to France in the early1980s. There she trained to teach English as a Foreign Language to business students. She bought a small cottage in the Rambouillet countryside and successfully bred Cairn Terrier dogs.

Unfortunately, she had always smoked heavily and this led to her contracting COPD, leaving her dependent on oxygen for the rest of her life. As a result, she became increasingly isolated, unable to make annual trips back to England. Her life was made more difficult with the recent death of her beloved sister Rosemary, but fortunately her sister Cheryl took on the weekly contact.

She continued giving free English lessons, some pupils remaining until the end of her life. She was very anxious about the impact of Brexit and the prospect of no deal, uncertain about the bureaucracy enabling her to remain living as a French citizen. She had loved living in the French countryside, attending dog shows, meeting friends, enjoying good French cuisine and listening to music. She will be sorely missed by her sister Cheryl and friends in England.

CHRISTABEL SHAWCROSS (1970)

Susan Deborah (Debbie) Sander (1970)

Debbie was born in Taunton, Somerset, in 1952 and grew up in West Sussex. At eight years old, family tragedy meant that she had to step up and care for herself and her younger sister, Ruth. Despite this challenge, Debbie made her way to grammar school where she dreamed of studying at Oxford. She achieved this dream, going up to Somerville College to read Physiological Sciences.

On leaving Oxford, Debbie quickly established the two themes that would be central to her life: education and helping the most vulnerable. First, she went to London to train to be a teacher. Then she moved to rural Nigeria, to work with children growing up in extremely challenging conditions. At university she had campaigned passionately against Apartheid laws in South Africa. The years she spent in Nigeria, and the work she did more recently in Tanzania, were part of a lifelong desire to see equality between Africa and the rest of the world, and to fight racism at home in Britain.

Moving back to Britain, Debbie spent much of her twenties working in London and around the world for the Commonwealth Institute, now part of the British Council. Part of her job was to seek out brilliant young artists, musicians and writers from around the Commonwealth and take them into state schools across the UK. Among the artists she discovered was the writer John Agard, winner of the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry.