Emma

Amanda

Linda

Liliana

Trevor Pasquali

Sketch

MINE

Natalee Ness

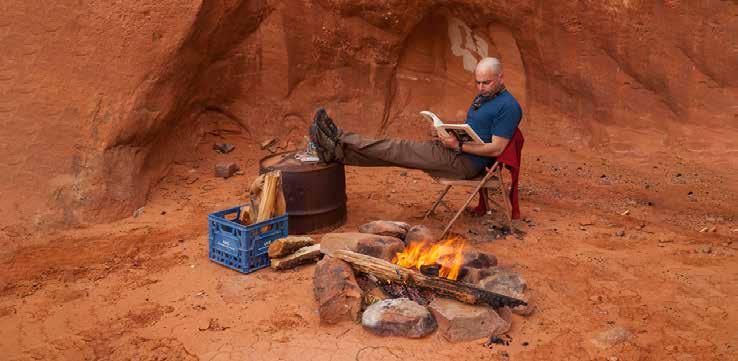

MINE alumni Ian Kerr combines his passion for journalism with his love for the outdoors and rafting to score a job with National Geographic.

Amanda Arch ContributedIan Kerr hiked through the dense forest of Denali National Park preparing to raft Wells Creek, one of the many undocumented raft locations in the state of Alaska. Conquering this creek not only made Kerr the first documented individual to have done so, but also brought him closer to his goal of rafting the entire Nenana River watershed. To fuel his journey, he carried a backpack full of supplies, a custom-gifted raft, and an arsenal of skills which have taken him from his childhood home in Springfield, Oregon to the raging rivers of Alaska. For many of these essential skills, Kerr has one place to thank. Kerr entered the Miller Integrated Nature Experience (MINE) as many others do, without a true understanding of what he was getting himself into. Due to its unconventional nature, the class sometimes at first serves as a sink or swim opportunity for students, nurturing those who have always searched for something different. Kerr had finally entered an educational environment that allowed him to pursue the sports he loved while also strengthening his academic skills.

One of the most vital skills Kerr learned during his time in the MINE program was the ability to step out of his comfort zone. In 2018, Kerr and fellow classmates Gabriel Cooper and Essence Roy flew out to the Oregon caves for a Backcountry Review feature. In order to raise money for the expedition, Kerr attended a rotary meeting where he gave a presentation regarding the program and its importance. As a result, Kerr was awarded with a $700 check in which the trio used to rent a plane to fly from the Eugene Airport to Selma in southern Oregon. They entered the Oregon Caves, which they reported on for Backcountry Review. This academic journey would have never been possible without Kerr’s willingness to reach out to others.

By harnessing his capability to put himself out there, Kerr turned his passion for rafting into a full-time career, securing multiple rafting sponsorships. “I’m more professionally ex-

troverted,” Kerr says when referring to his ability to contact helpful resources since his experience with the MINE program. “I know people that have been rafting things way harder than me, 15 years longer than me, that aren’t sponsored. It’s just because they don’t reach out.”

During his time as a Springfield High School student, Kerr had a passion for cycling, swimming, and the outdoors. This passion soon evolved into something much more when a friend and fellow member of the swim team introduced Kerr to the world of kayaking. With no gear of his own, Kerr took to the water with University of Oregon rental gear. Ever a fan of environmental exploration, the experience proved a life-changing event, later opening new doors for Kerr.

Now with an insatiable hunger for kayaking, Kerr continued for three years. Afternoon kayaking trips soon evolved into overnight expeditions, but Kerr was faced with a dilemma. His beloved kayak offered little space for his gear, so he left the vessel in search of a more spacious raft. Suddenly, the possibilities seemed endless and Kerr wasted no time planning his next journey.

On his first excursion, Kerr took to Oregon’s Illinois River, where he met a character by the name of Chrisissippi (Chris from Mississippi, obviously), who worked for a white water rafting company in Alaska called Denali Raft Adventures. Chrisissippi shared his stories from rafting in Alaska, and the beauties beholden to Denali National Park. Discovering that he could make a successful living all while feeding his passion for rafting, Kerr immediately expressed interest in becoming a river guide. He soon purchased a one-way ticket to Fairbanks and packed his bag.

Kerr learned how to guide many gorgeous rivers in Alaska, starting with a 22-mile strech of the Nenana River southwest of Fairbanks. Over the course of three seasons, Kerr went on to privately raft all 140 miles of the Nenana River watershed,

River guide Ian Kerr celebrates a run down Wells Creek in Alaska.

River guide Ian Kerr celebrates a run down Wells Creek in Alaska.

the distance spanning all the way from the Nenana Glacier down to its confluence with the Tanana River, a much larger river that flows into the Yukon River. With a friend, Kerr rafted all of the individual tributaries leading into the Nenana.

To raft some of these river sections, he had to bushwack through the dense forest of the Denali National Park. Kerr recognized a need for a lighter, more compact raft. This led him to seek out a rafting company called State Of The Art Rafts (SOTAR), based in Merlin, Oregon. Aware of Kerr’s Nenana project, the company built him custom rafts which were both light and easily foldable, perfect for his hike-in rafting needs. He was gifted these rafts free of charge with one condition: he needed to act as a SOTAR sales representative for the state of Alaska. Grateful, Kerr accepted the opportunity and took off with his new rafts, one of which he went on to use for the Wells Creek expedition.

Today, Kerr lives on a gorgeous piece of Alaskan property, the Kilcher Family Homestead, featured in the National Geographic program Alaska: The Last Frontier. He considers the Kilchers more friends than landlords. Living on one of the most famous homesteads with a National Geographic featured family was just one of the perks that came with Kerr’s ability to create and seize opportunities.

Between his connections with National Geographic and his impressive rafting capabilities, it was not long before Kerr was on the network’s radar, contracting for them on rafting expeditions. Kerr quickly accepted National Geographic’s request for him to work on a season of their popular television program Life Below Zero, working as a rafting guide to take camera equipment and videographers down a select few rivers to follow some of the show’s characters. Kerr was hired by the team as an official expedition safety manager.

Today, he continues to work on Life Below Zero as well as other projects. From cultivating a love for rafting to using his skills as a journalist to secure deals with successful brands, Kerr is no stranger to finding what he wants and claiming it as his own. As a high school student who believed college was not an option, Kerr embraced the opportunity to follow his passion and develop his talents rather than settling for a more traditional path. As a journalism student at Springfield High School, Kerr learned the importance of controlling your own narrative and carving a path for yourself.

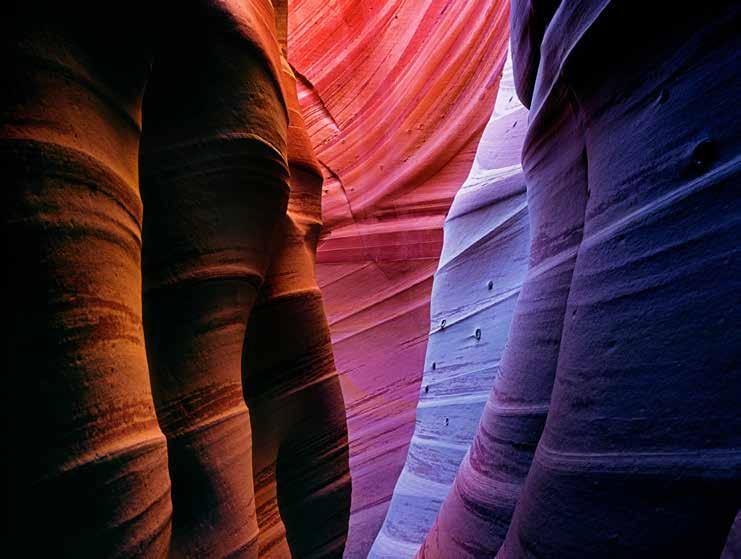

Amidst the sprawling landscapes of the diverse Israeli countryside, Guy Tal felt a sense of freedom in the outdoors that was absent within the walls of his empty childhood home. Often left to his own devices, he ventured into wild landscapes surrounding his town. This exploration and eventual self-discovery spoke to his soul.

Growing up, Tal describes himself as an introvert, which resulted in a high degree of self-sufficiency. Tal often wandered hours away from home, sometimes spending days at a time alone. Meanwhile, Tal found healthy escapes in the form of books, heavily influenced by the virtues of the developing characters.Yet, Tal could not help but feel a sense of separation between his love for reading and his passion for the outdoors. The two realms, though both offering escape, seemingly existed in parallel universes. There was a time for hiking and exploring, and there was a time for reading. But this paradox led to an important epiphany.

“There are a lot of people that will go out and say YOLO–you only live once. Most of these people wouldn’t dare do anything commensurate with that statement,” says Tal. “But for me, I’m one of the few that took that seriously. I only get one go and I want to make it as interesting as I can. And it’s worth taking some risks for. And that’s what I did. That’s an awesome way to live life.”

infringed upon by rapid urbanization.

After his military service, Tal studied finance at Tel Aviv University during the early 1990s and began working for the computer lab which granted him access to the internet, leading him to create some of the first commercial websites in Israel. As the internet boom hit throughout the world, Tal’s skills in network management quickly became desired by many tech startups, including a few in Silicon Valley, which offered a 30-day contract. Tal thought to himself, “I could just sit here and wait, or I could just get a job in internet technology which was exciting at the time. And I decided on the job and ultimately [it] brought me to the U.S.”

Tal settled in Santa Clara, California, where his 30-day contract turned into a new life in the United States. Tal, still enamored of the canyon land Abbey described in his book, took road trips to southern Utah, and quickly found his “love at first sight.” Over the next few years, working for several tech start-ups in Silicon Valley, Tal began his own financial consulting business and met his wife while she was studying at Stanford University. Still taking trips to Utah whenever he could, Tal’s itch to be closer to the desert grew with each visit. An itch he eventually scratched when his wife was accepted into law school at the University of Utah.

As a mandatory service in Israel, Tal joined the military shortly after graduating high school. Unlike many of his peers who were eager to join the military, Tal’s personality often clashed with the regimented aspects of military life. In a life strictly governed by hierarchy and discipline, Tal yearned for the freedom he once had.

Tal served in the late 1980s when the infamous First Intafada of Israel occurred. The civil uprising was carried out by Palestinians in Israeli-controlled Palestinian territories. Amongst the 80,000 soldiers deployed around Israel, Tal ostensibly trained to fight wars as a soldier but found himself primarily policing civilians, many of whom were young teens. For Tal, this proved unsettling. He says, “this did not sit well with me at all. Just some of the things I’ve seen and the way that it made me think about the politics of the Middle East. And it was very obvious to me that I did not want to be a part of that.”

As Tal’s service in the military came to a close, he discovered a book written by well-known author Edward Abbey called Desert Solitaire. Reading about Abbey’s experience as a park ranger in Arches National Park, he could not help but fall in love with the ideas and imagery of America’s untouched southwestern deserts, perhaps reminding him of the experiences he once had in the landscapes of Israel that had been

Tal stayed in Salt Lake City for ten years working at a financial company, and despite his many material comforts–nice home, secure job, and well-paying salary–Tal still felt dissatisfied with his life in Salt Lake City. Although his job offered security, Tal’s regular visits to parts untouched by rapid urbanization brought him a great sense of comfort. As he read philosophy and stories of great adventures, Tal and his wife decided to leave behind their careers and buy a home in the small town of Torrey, Utah to pursue a life Tal had been yearning for.

Tal’s teenage years were marked with insatiable curiosity, and his dad’s old camera was an instrument that helped him to “study things very closely and then start to think about how best to portray them and to arrange them.” Tal adds, “it was a form of really deep engagement with things that were already very interesting.”

Years later in Utah, Tal rediscovered his creative spark, photographing everything from a macro level, especially trophy-worthy landscapes. “That’s always been the main driving force is to try to discover this beauty, this hidden arrangement, this emotional effect that you could distill and evoke.” All these years later, the outdoors still provides an endless source of fascination, allowing him to be “even more intimate with them.”

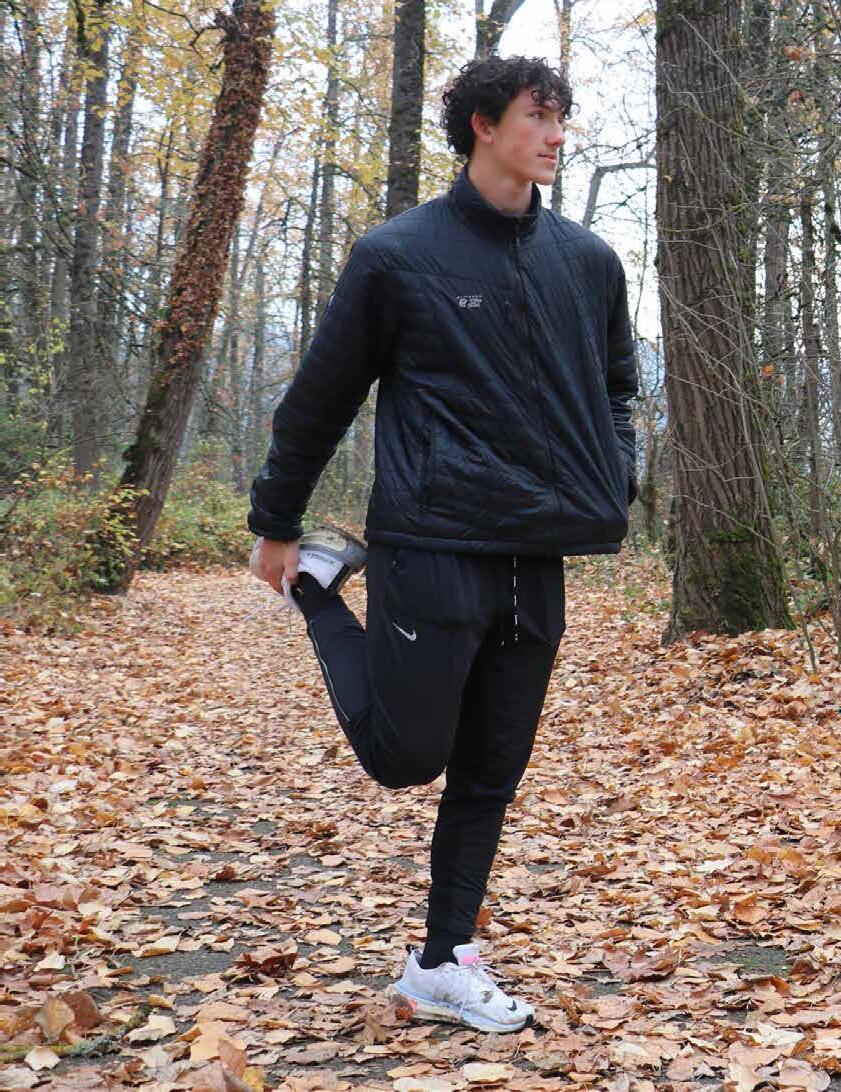

Jordan Bodenhamer reflects on his experience completing the 4x4x48 challenge and the personal growth it provided.

Jordan Bodenhamer Madison Blaine“This is too much on my body,” I thought to myself. My mind pulsing, it felt as if my head was going to run out of room, my thoughts on the verge of exploding out of my skull. The rules of the 4x4x48 Challenge were simple: run, bike, and walk four miles every four hours, 12 runs total, for two days straight, finishing with a total of 48 miles.

I was not even halfway through my sixth run, and I was already unsure if I could finish. I had already run 24 miles on asphalt roads, heated from the long days of July and the tendon behind my right knee felt as if it had been pierced by a sharp knife, all that was left was a string using all of its strength to hold itself together. Pain took hold and the idea of pushing through and finishing seemed to fizzle in the heat.

“If I don’t stop and walk now, will I be able to run again?” I thought. “Should I stop?”

I completed the four miles. To this day, I do not know exactly why I did not just stop and walk, but I know something bigger was driving me.

Former Navy Seal, best-selling author, and creator of the 4x4x48 Challenge, David Goggins grew up with many struggles and adversities, living with an abusive dad, experiencing racism, and seeing violent things kids should be shielded from. In his autobiography Can’t Hurt Me, Goggins writes about his father get-

ting drunk, and later attacking his mother. His dad kicked down their bathroom door and slapped the mother until she was barely conscious. Attempting to protect his mother, Goggins wound up getting beat with a belt.

Because of this abuse, Goggins thought of himself as a loser and tended to give up when life got difficult, resulting in a spiral of depression. Things did not get much better during his teenage years. He started binge eating as a way to cope with his demons and grew extremely overweight, making it hard for him to live a normal life and get a good job as an adult. Working at Ecolab, spraying cockroaches for different businesses and restaurants, he was only making $1,000 a month and hated it.

One night after work, after finishing a chocolate shake and a dozen mini donuts, he turned on the TV and heard, “Navy SEALS, toughest in the world.” Paying close attention, the program covered all the hard work the SEALs had to do and what kind of people they were.

Goggins immediately searched for a recruiter and after failing many times he found one who enjoyed finding “diamonds in the rough.” He told Goggins that within three months he needed to score at least a 50 on the ASVAB test and lose 106 pounds. At first, Goggins did not think it was possible but his extreme obsession and determination took over.

“I’d wake up at 4:30 a.m., munch a banana, and hit the ASVAB books,” he wrote. “Around 5 a.m., I’d take that book to my stationary bike where I’d sweat and study for two hours. Remember, my body was a mess. I couldn’t run multiple miles yet, so I had to

Writer Jordan Bodenhamer stretches before a run on Pre’s Trail.

Writer Jordan Bodenhamer stretches before a run on Pre’s Trail.

burn as many calories as I could on the bike. After that, I’d drive over to Carmel High School and jump into the pool for a twohour swim. From there I hit the gym for a circuit workout that included the bench press, incline press, and lots of leg exercises. Bulk was the enemy. I needed reps, and I did five or six sets of 100–200 reps each. Then it was back to the stationary bike for two more hours.”

Goggins understood he would not receive an apology for how he was treated. He realized he needed to move on, embrace his weaknesses, and suffering showed him where he had room to grow, how he could turn those weaknesses into strengths.

When my friend asked me to do the 4x4x48 Challenge, we devised a plan. We set the start time at 8 p.m. so we could follow an even cycle of 8, 12, 4, etc. The day before we started, I talked to my dad and told him exactly what I would be doing.

His response: “You are crazy.”

Then he gave me the worried parent talk–I needed to be careful, not over train, etc. But despite the concern, he still wanted to see if I could complete it all.

I lift weights every day at 5 a.m., have played basketball almost my entire life, and participate in varsity track and field, but this challenge was on an entirely different level, for both body and mind. Yet, that is why I wanted to take it on, to prove to myself that I can achieve anything I truly wanted by putting in the work, and maybe gain a deeper understanding of myself.

I only had time for roughly three hours of sleep in between each run and after two days it was starting to take a toll. I knew it would be important to stretch and use a foam roller to keep my body functioning.

I started a little slow on the first run, knowing I needed the energy for the later runs, however, I quickly switched to my normal “easy” pace at about eight and a half minutes per mile. It felt like my entire body was in sync, every muscle and nerve working towards the same goal. It was almost as if I did not have to try to run. I felt confident as I got home, ate dinner, and felt I did not need a nap between my first run and the upcoming one at midnight.

Before I left on my second run I got hit with a sudden wave of fear. It was very dark outside so I grabbed my keys and drove to the nearby Albertsons parking lot and began running from there,

comforted by street lights. I ran circles around the parking lot, which became insanely boring.

Then two miles into my fifth run, it seemed like I was wearing ankle weights and weighted sweatpants. Afterward, I emphasized stretching, even turning to a massage gun. Unfortunately, the next run changed the course of this challenge. It felt as if a knife had slit the tendon behind my knee, the pain immense and sharp. Later falling into a reclining chair, I was immobile, icing on and off again. I sat there the entire three-hour break, only moving with about 20 minutes left before the next run.

During the sixth run, I decided to walk because of the returning pain. In that moment there was nothing I wanted more than to finish, and I had to prove that I could. The run felt never-ending and mentally exhausting. That’s when I remembered the video of Goggins explaining the rules: “Run, bike, and even walk if you have to.”

So I grabbed my bike. It was painful to ride, but not as intensely as running. Because biking was easier, I upped the gears so I didn’t feel like I was making it easy. I repeated this for the next three cycles.

At 7:45 a.m. I felt ready to run again. Lifting my feet one after another became tedious, my quadriceps screaming. During the final run, my dad trailed me on his bike. Three miles in, every muscle and fiber in my body started giving out, but I pushed myself and finished with the fastest average pace I had during the entire challenge.

Goggins’s mission is one of pursuit, always working to improve. In his book Never Finished one of the main ideas is to strive for more, regardless of the accomplishments. When I embarked on this journey, his mission and my goal were at an equilibrium. There was a point when I was not sure I would finish. I had one of two options: give up or push for a higher standard.

Some people choose to shy away from challenges, scared of what would happen if they were to try. They stay complacent, and sometimes this results in lasting depression and regret. Some people do not recognize that if they were just to push a little harder they could accomplish so much. Sometimes this means feeling humility from all the times they had to fail to get there. What is much scarier is coming to the end of life, looking back, and regretting not doing more. But there is much to learn from pushing past perceived limits.

Jericho Truett searches for a glimpse of solitude while backpacking overnight in the Willamette National Forest.

Truett Blaine

Blaine

I left school at 3:05 with the idea of escaping the city at the forefront of my mind. I navigated frustrating after-school traffic, watching the minutes tick by on an old analog car clock (3:18). Once I got home, I started packing, immediately realizing that there was no space for my stove in my pack. “That’s fine,” I thought, packing some canned chicken and tuna, and most importantly the pickles.

I grabbed the first sleeping bag I saw, sweating and swearing, trying to get everything to fit in my bag, the zipper seams on the verge of bursting. I got into my car and walked back into my house five times, forgetting something on every trip, my brain beyond on the verge of explosion.

With my backpack, sleeping bag, and other necessities accounted for, I turned over my key and left for the second time (4:45). I hoped to beat rush hour traffic and arrive before dark. As the never-ending trail of taillights gave way to dense forest my mind finally relaxed, a little. The plan: drive up to Linton Lake, set up camp, relax by the water, do some hiking, find refuge from the chaos of city life. But of course nature has its own plans.

With the sun sinking on the horizon, casting an orange-pinkish hue across the sky, I pulled up to the trailhead, parking at Alder Springs campground with no other cars in sight. I ventured into the woods, following the trail towards the lake. With each step bringing purer air and crisp forest smells, a mist enveloped my backpack and it started to sprinkle as I traced the lake’s edge. Finally arriving at the vast alpine crater, my heavy bag jostled on my back with every step, its rhythm syncing with my heartbeat. Rain streamed down my face. As the night’s shadows deepened, I could not help but yearn for the comfort and safety of my tent, but in the pitchblack, even seeing my own hands seemed like a challenge.

As darkness cloaked the landscape, I started searching for a camp spot. Going further down the trail towards an unnamed

waterfall, the trail became less distinguishable from the blowdown from the previous year’s wildfires. I was waist-deep in brush, my entire lower body soaked, as the rain intensified. As I walked back, the forest started to speak in hushed tones— an unseen world of animals and plants hum-buzzing to a cosmic pulse. Time seemed to stretch endlessly in the dark, the symphony of nature jamming on. As it got darker, finding a spot to camp became imperative.

Then a soft thud broke my trance, followed by a low growl behind me. I started walking faster, my heart pounding, my vision blurred. Rocks collapsed behind and I started running, desperately hoping to escape the presumed threat. Shivering, I ripped my tent out of my backpack, setting it up in record time. Unfortunately, I literally could not distinguish which side was which for a good ten minutes, soaking my whole tent. I played with this non-euclidean object until the puzzle came together. After staking the tent I shoved my overstuffed pack and weary bones into it. The rain soaked through the tent onto my damp skin, the shivering growing worse.

I was pissed, ripping open the fly and crawling out into the pouring rain, in my soaking wet shoes to re-stake my tent, however, the ground proved too muddy. I grabbed my phone light and looked back through the streaming rain (8:49). I nestled into my sleeping bag to avoid hypothermia. The fly failed to cover the tent and moisture slowly seeped through, puddling up in the corners of my tent. I shivered in the darkness, lying in my soaking coffin, but I thought it was quite funny, even exciting.

Truthfully, I was not on the verge of death, just uncomfortable. And that was okay. Maybe we are not supposed to be comfortable. Laying in the corpse pose throughout the night, falling asleep for minutes at a time, constantly waking to the patter of rain falling, the cold drip soaking into my skin, I found myself laughing at the situation. There was a warm

Madison Jericho

Jericho Truett takes a moment to rest in the forest shade.

Jericho Truett takes a moment to rest in the forest shade.

comfortability and clarity that came with the complete chaos of it all. Eventually falling into unconsciousness, I found some odd sense of peace.

Waking to darkness, I began shivering as I felt around my wet tent for my phone, feeling as though I had not slept a minute (12:32). Turning the flashlight on, I could see a puddle of mud had filled up the tent and soaked all my belongings. I dared not move a muscle for fear of drenching myself even more. As I yanked the zipper up on my sleeping bag it ripped right off the stitching, leaving the bag half open. Damning myself, I pulled it and held it shut in a frail attempt to keep warm. I hoped to sleep through the sheer discomfort of the frigid night, but I had no chance of getting any rest in such dire circumstances. Holding myself tight, I blew hot air on myself and hoped to avoid hypothermia.

As dawn broke, a dim gray light gleamed through the collapsed tent, illuminating the chaos of the night before. Climbing out of the wet pile of fabric, a mist overtook me and wet my eyes as I stumbled for my shoes. I should not have left them outside. My phone was dripping wet and smudged (5:06 a.m.). I gathered all my stuff together very slowly, stiff from the extended freeze. “Leave no trace,” I thought to myself as I struggled to shove everything back into my pack with numb fingers. Once I had everything together, I trudged back. The early morning sky appeared cloaked in an overcast gray and the earth beneath my feet consisted of mushy leaves and mud. Each step provided a squelch, a symphony of water and earth that stuck to my boots, making every movement a battle against the trap of the forest floor. The rain, no longer a torrent but a drizzle, left a pattern of droplets on my skin, each one a cold kiss from the sky. The trees, their branches bowed under the weight of the rain, dripping on me as I passed them. My clothes felt like a soggy second skin, the fabric clinging desperately, every fiber saturated with the essence of the forest. The cold, my new enemy, left me shivering with each step. The path back was a process of determination, each step a testament to resilience. The familiar trail now seemed alien but driven by a deep-rooted instinct, I pressed on, each step empowering me to take the next. At last, my car appeared through the mist, a promise of warmth and respite. My fingers uncooperatively wrestled with the key, but the door finally opened and I sank into the seat, immediately soaking it.

The steady hum of the engine was a comforting sound against the soft rain as my wheels spit water on all sides. As the miles unfolded, the ordeal of the night truly materialized in my mind. The struggle against the rain, wind, and cold were not just hardships but chapters of transformation, a plodding development of persistence and endurance. Soaked. Chilled. But undefeated. This was not a tale of the harshness of nature but of resilience and spirit.

Free diver and champion spear fisher Kimi Werner embraces her relationship with the ocean and deepens her connection with family.

Out in the ocean, rocking and bobbing on a boat ready to start her dive, Kimi Werner takes a few last deep breaths and then merges with the sea. Werner’s body slips in, the compression of the water surrounding her, the peaceful silence enveloping her. A few quick, still strides and she dives deeper into the reef below. The colorful coral and exotic marine creatures light up the water.

Her body only admits small swift movements as she searches for tasty fish or octopus. Then suddenly she spots a fish moving effortlessly in the water. She angles her body, aims, and then fires. The spear and the line come shooting out and soon the fish flops limp around the blade.

For Werner, life is a lot like the ocean, constantly changing. Regardless, Werner always thanks the fish for the food it will provide. Werner’s connection to the ocean means understanding its significance. Once submerged, she has to give up some control and work with the water. Some days the ocean can be fast moving and others calm and cool. Werner has learned to love that unpredictability.

“I think that’s one thing I have learned to accept and embrace about life itself, that you never really have it figured out,” says Werner. “And that is the beauty of it. That’s why I love the ocean because I can go back to it every day and never really have it completely figured out.”

Going to the same coastline, seeing new beginnings every-

day, Werner adapts to the ocean, absorbing all of its lessons. As a result, Werner is a national award winning speargun fisher who truly cares about the ecological community and fully embraces sustainability. Werner has done a TedTalk on speargun fishing as well as the importance of environmental impact. She has won multiple championships and awards, including first place in the International Pacific Cup and first place in the 6th annual Gene Higa Tournament for Spearfishing. In 2013, Werner was the first woman and youngest person to be inducted into the Spearfishing and Freediving Hall of Fame, and she did not stop there. Earning several environmental awards along the way, Werner has exemplified true dedication to the natural world.

In a 2014 Ted Talk, Werner dives into her early experiences with spearfishing, explaining her first encounter with a shark and how slowing down, instead of speeding up, saved her life. Trusting herself and her skills has helped maintain a delicate balance throughout her unique life. Among all the wondrous adventures, competitions, and life-changing events, nothing compares to giving birth to her son, Buddy, a moment that shaped and defined the person she is today. The ocean and her son’s birth story are interlinked and the same tools she used to conquer a fear of sharks is something Werner used in the delivery room–having to slow down and think things through.

At 38 weeks into her pregnancy, equipped with a mother’s intuition, a panic suddenly hit that something was not right. While on the way to her doula (a midwife) to get her vitals checked, she was stopped by traffic. Werner decided

Lucy Rogers Justin Turkowskito turn around, then texted her doula she would not make it. However, the feeling did not go away and just to be safe Werner decided to go to her primary care doctor to get her vitals checked, and it was a good thing she did. Her blood pressure was through the roof and more medical concerns arose. Werner was faced with the tough decision to give up her home birth plan and have an emergency C section.

For Werner, this beautiful and terrifying event helped reveal that new paths are not always as scary as they seem. Times that people may veer from the plan can sometimes work in their favor. Werner says, “all of a sudden, the birth that I never wanted, ended up being the most magical experience of my whole life.”

Werner believes that our souls are not linear, that humans are supposed to be pulled in different ways and fall down just to get back up and try again. She believes accepting failure and living through mistakes offers an opportunity to learn, which has benefitted her in motherhood and her career. Werner says, “the thing about failure or fear or shame, it thrives when you try not to feel these feelings or you hide away these feelings.”

She adds, “I have a really hard time calling anything a failure because it somehow evolves into a whole new starting point, and learning experiences, and that’s a valuable thing to have in your life.”

Some might wonder how a mother juggles a kid, spearfishing, public speaking, and activism, but Werner thinks that the juggle is more of a balance, a circle, where everything on

her plate receives special attention, thereby making her feel whole. Werner says, “I feel like a shell of a person when I don’t do the things I’m passionate about.”

By acknowledging her emotions, she hopes to help build a more accepting community, something she first learned as a child, watching her dad provide for her. Early on, Werner went on speargun dives with her father, learning the art of the hunt and growing to appreciate how food was brought to their table. These dives would become a big part of Werner’s life in the years to come. Now a mother, always a passionate environmentalist, Werner has found creative ways to share her wisdom with younger generations of women, admitting their imaginations hold “no bounds,” suggesting they are neither tethered nor anchored down. Werner hopes they use “that young boundless version of themselves as their compass in life.”

Whether Werner is battling strong currents or bedtime, she remains connected. She sports an imagination without bounds, and sees life as a constant learning opportunity, seeing failure in a positive light and using it to grow, especially in her career and as a mother. Accepting that she cannot stick to every plan and has to let go of control every now and then, Werner has and will continue to slowly move toward her aspirations and dreams, always striving for balance.

Werner shares her passion for spearfishing with her family.

Philip Henderson helps under served commnties to explore the outdoors and discover its benefits.

Grecia Sigala

Contributed

In the first eight years of his life, Philip Henderson spent most of his time at church with his family and local community. During those years, he attended an all-black school and lived in an all-black neighborhood in San Diego. However, in 1972, his father bought a home in the suburbs of Southern California. Suddenly, Henderson was one of a few black kids at a predominantly white school, where Henderson never really felt like he was accepted. Many times in class, he would raise his hand, only to have his teachers and peers look past him as if he was not there. He was called names and had rocks thrown at him on his way to and from school.

Trying to find any way to avoid these situations, he searched for detours on his way to school, noticing little things that he had not before, like the different petal shapes on the flowers and the busy ants walking in a straight line. Nature and the

outdoors intrigued him. The detours proved relaxing, a time of peace before the storm that was school. These strolls led to a love of the outdoors, the memories forming the core of his childhood.

During Henderson’s TEDx talk “Let Detours Become Your Strength,” he discusses the memories that led to his passion: “My uncle Hersey… he took the time to take me fishing, and that was something that stuck with me… It still sticks to me to this day, and it was kind of a lifesaver.”

Back then, it was not easy for Henderson to go out and experience the outdoors. Research has shown that racial minorities, as well as lower-income individuals in the United States, are historically less likely to engage in outdoor activities. Multiple underlying factors have led to this, one of them being redlining, a practice in which banks and other institutions limit or refuse loans, insurance coverage, and other financial services to residents in specific neighborhoods based on their racial or ethnic background. This makes it challeng-

ing for minorities to live in areas where nature is accessible.

According to the 2022 socioeconomic monitoring of National Park Service (NPS) visitors’ report, the NPS conducted onsite surveys where national park visitors were asked questions about their racial identity, finding that 93 percent of the respondents were white. Meanwhile, people of color make up 43 percent of the total U.S. population according to the 2020 census. Helped by his uncle Hersey, Henderson’s experiences allowed him to unwind from daily stress and feel what many others do not experience.

This also prevents a larger sense of community, which Henderson longed for after moving to the suburbs. Henderson played football and baseball throughout his early life, and at first these sports became a bridge that connected Henderson to the community he yearned for. Unfortunately, his college football career ended abruptly after a game in which he ended up fracturing a vertebra in his neck, which left him paralyzed for two minutes. During his recovery, he was no longer able to participate in team sports, his dream of becoming a professional football player shattered, and the sense of community he found soon disappeared. As a result, he posed a serious question: “What am I going to do for the rest of my life?” He remembered his childhood and the fun times spent outside. Henderson says, “the outdoors was something I gravitated towards.”

In 1992, Henderson entered the outdoor industry, where he has since taught outdoor classes of every kind, from guiding white water rafting in the summer to ski instructing during the winter. In many ways, Henderson paved a path for himself and others from similar backgrounds.

“It was a process of being comfortable [and] being able to do things, but also learning that there was even an industry,” says Henderson. “I’m a black person. I didn’t grow up with the outdoor industry. So it’s not something that was accessible.”

Henderson searched for any sense of representation in the outdoor world that he could look up to and learn from. He says, “I had to learn on my own. I didn’t learn from people in my community because there were no people.”

With his passion for the outdoors and education, Henderson began to work at the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) in 2002. NOLS is a non-profit organization that specializes in providing outdoor education to individuals who seek to acquire technical skills in various outdoor activities. Their programs focus on environmental ethics, wilderness medicine, risk management, and leadership on longterm wilderness expeditions. Henderson immersed himself in month-long NOLS leadership training courses where he developed a blueprint to build community outdoors.

Years later, he founded Full Circle Expedition, which strives to create a space for individuals to feel inspired, represented, and supported in the outdoors. In 2022, Full Circle made history and became the first all-black expedition to attempt to summit Mount Everest. Although Henderson did not summit himself, the expedition was a success, and seven members of the Full Circle Expedition reached the top with his guidance.

Henderson’s work with Full Circle Expedition and dedication to advancing representation in the outdoor recreation industry has given him a purpose. He uses his 30-plus years of experience in the field to inspire, empower, and support the upcoming generation of outdoor recreation enthusiasts. With the success of the first Full Circle Expedition, Henderson does not intend to stop anytime soon.

“I made sure that people knew that Full Circle Everest is not a one-and-done,” he says. “It’s the tip of the iceberg.”

In the future, Henderson and the rest of the Full Circle team plan to organize educational speaking events as well as more guided expeditions. With these future activities, Henderson aspires to motivate, energize, and advocate for connection to nature for everyone.

Henderson’s childhood detours through nature led him to discover a love for the outdoors that has shaped his life’s work. Exploring the world around us and taking detours can benefit anyone. Whether it is a walk in the park or a hike in the mountains, connecting with nature can provide a sense of peace, inspiration, and community.

-Original reporting by Landon Cowan

Running through Canyon de Chelly on a sunny Arizona day, chasing turkeys and deer, Dustin Martin was exhilarated to be in the canyon and leading the 55 kilometer race. The Canyon de Chelly Ultra Marathon runs 17 miles along rugged terrain before turning back to the start. Ten miles from the finish line, he started to fall apart, feeling discomfort he had never experienced before, his legs nearly giving out. Regardless of the pain, he managed to finish the race in second place. This race allowed Martin to push his limits in a way he never had before, discovering a new threshold of pain. He remains extremely grateful for the safety net of people around to help, feeling he probably would have died had he been alone that day. As a result, Martin now recognizes that his ancestors did not have that luxury when they had to travel long distances.

Martin was raised in Gallup, New Mexico, where he was surrounded by running. His mom was a track and cross country coach, and some of his earliest memories were playing with his toy trucks on cross country courses. Martin says watching all of these runners doing amazing things really inspired him.

He is now the executive director of Wings of America, a program that empowers native youth and their families through running. They recently bought a headquarters building in Albuquerque, New Mexico, but the organization is almost national in scope as they have programs running all over the country.

“Wings is a reminder to our young people that in order to have a true or well informed relationship with your landscape and your ancestral homeland, you also have to commune with it and communicate with it and that can be done through your feet, but also with people and with friends,” says Martin. “I think ultimately Wings provides a safe space for Native youth to engage in an activity that can be very difficult and intimidating for some. But with a community it becomes easier and more rewarding to engage in.”

When his parents divorced during middle school, Martin and his mom moved to Albuquerque. Feeling lost and unsure about what his next steps were, Martin rode his bike around the neighborhood,

searching for friends and a community, and eventually, he found it in a group of friends he is still close with today. Looking back, Martin thinks some of that lost feeling came from the fact that he is always very motivated by others. Without a community to challenge and inspire him, he did not know what to do. Martin thinks this idea applies to everyone, that very few people have ever done anything without inspiration and help from others.

In high school, Martin ran for Albuquerque Academy, where he learned a great deal about community.

“I also always give a lot of credit to the runners on our team that helped sustain and build this culture of accountability and excitement,” he says. “Even though they weren’t being celebrated at the same level that varsity runners were, they still had to do all the same work and all the same workouts. And I feel like I was always good at recognizing that and appreciating that.”

Martin thinks the community built on running teams and during

races is unlike any other.“We’re able to recognize each other’s humanity when we watch and we feel each other running,” he says.

Running also brought him closer to his roots.

“I think it has helped me develop a sense of empathy as well as a sense of belonging within my Diné or Navajo identity that I didn’t always have as a young kid,” says Martin. “I’m half Navajo on my dad’s side. My identity was always questioned, so of course I questioned it myself. But being able to work for Wings and to work with other tribal youth, there’s a sense of confidence and a sense of belonging that I have now that probably would not have been possible had I not been a Wings runner or been able to work for Wings for the past 12 years.”

Martin says that oftentimes when someone comes from a small rural town or a native community they are led to believe that they come from a place of disadvantage and are not embodying the American Dream, a term Martin is not fond of. People feel like they have to leave and find more opportunities elsewhere. One of the main obstacles he

had to overcome was shifting his mindset to understand that it is a gift to have knowledge and a connection to his ancestral homeland. It took a lot of stepping out of his comfort zone and putting himself in places he did not feel he belonged for Martin to find that perspective.

“As an agent of Wings, and to share with other people, especially young brown and black people that don’t ever see your background or where you’re from, yes, it can be very difficult and there can be very ugly pieces of our community or the way that we grew up,” says Martin. “Ugly pieces of our community or the way that we grew up that challenge us, however, they also strengthen us and allow us to provide a perspective that a lot of people are desperately seeking. They want some form of connection or some feeling of belonging. And for me, I don’t look for that because I know where I belong and I know where I’m from and I know that if the world fell apart, I would go right back to the Navajo Nation and I would be okay.”

Martin knows that success is not linear and that people do not have

to be the best at something for it to be a job well done. He thinks people should not judge themselves based on someone else who is “successful” because comparison is the thief of joy.

“The older I get, the more I understand and appreciate the reciprocity that is necessary for anyone to succeed…like people in races; people are only distinguished as the winners because all those other people showed up to run as well,” says Martin, further suggesting it necessary to recognize “their effort and their sacrifice.”

He adds, “I have to continue to remind myself of that. I have to surround myself with those people and call in my community because that’s how I find the best version of myself.”

In a world full of pressure and high expectations this lesson is a valuable one. Your best is enough; the only person you have to compete with is yourself. If people take a minute to be grateful for everything they have and can do, they can learn to be content with where they are at.

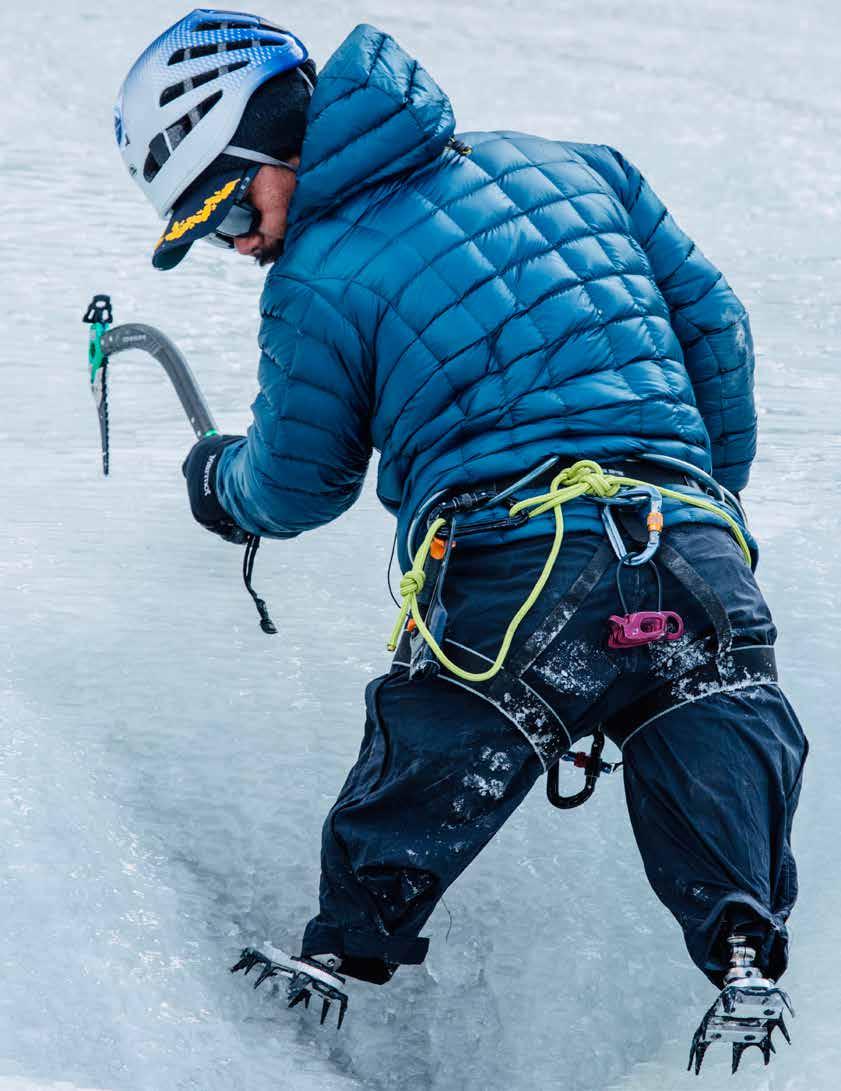

Red Bull athlete Sebastián Álvarez uses his knowledge as a pilot to fly over an active volcano in a wingsuit.

High in the skies of the Chilean landscape, staring down at one of the most active volcanoes in South America, Sebastián Álvarez, a professional wingsuit flier for Red Bull, dared to do what no man had done before. He planned to execute a carefully crafted “flare” technique inside Villarica’s crater, a wingsuit maneuver using vertical speed, generating lots of energy, transforming it to horizontal speed, and then transitioning into vertical speeds that would allow him to fly upwards. He planned to swoop in and out of an active volcano with only the wingsuit and a parachute. Sitting in the helicopter moments before, tensions soared. The wind fiercely ripped across the sky as the helicopter flew higher and higher, two miles up in the air with the crisp, cold wind hitting Álvarez’s face.

The sound of walkie-talkies crackled: “We are in position, ready to jump.”

Álvarez stepped onto the frozen bars of the helicopter. Looking out into the cloudy horizon, he took one more deep breath. His team nervously counted down, “dropping in three, two, one… go.”

Jumping from 11,000 feet, the wind immediately blasted his face as he rapidly raced down at approximately 144 mph. He focused on all the small details in his mind, being fully aware of his speed, wingsuit, wind patterns, and anything that could throw him off his path or fly him into a wall. Villarica’s smoky crater in sight, his trajectory looked promising. He quickly descended lower. In a tense moment, he swooped right into the basin. The team nervously waited. A total of three seconds passed with Álvarez inside.

One. Two. Three.

Flying right through the balmy smoke, feeling the immense heat of the volcano, and risking his own life for the love of flying, Álvarez used his speed to push up and fly right out of the crater—a feat no human has ever done. Pure exhilaration followed, cheers went up and all previous anxiety lifted. Álvarez

did a barrel roll to celebrate the extraordinary feat, embracing the monumental moment.

Growing up in a small town in Reñaca, Chile, Álvarez was not always high up in the skies. Closer to the beaches, he remembers spending lots of time swimming in the ocean and first started surfing around age 10. His older brother’s love for surfing inspired him to start competing at an amateur level, eventually landing him on the Chilean national surfing team. Álvarez recalls giant waves wiping him out, often leaving him unable to ride the rest of the day, for he “was scared, tired, and full of water.” In school, learning how to play different sports, he knew he wanted to be a professional athlete. He says, “I knew it was going to happen somehow because it was a big dream that I had, I just didn’t know which sport to choose.”

At 17, Álvarez was ready for a change and entered the Chilean Air Force to become a pilot. Over the next eight and a half years, he learned that nothing is impossible with lots of hard work and a willingness to collaborate with a team. Learning discipline was the biggest challenge for him. He says, “to do things that you don’t want to do but at the very end, you realize they are teaching something important.”

During his military training, he learned how to survive in the oceans, deserts, mountains, and forests. Training in stressful environments, he bonded with teammates, some of whom he still talks to today. He went on to become a decorated pilot and an engineer, learning to appreciate the struggle involved. Álvarez quickly developed a passion for flying, spending all of his free time skydiving.

After moving to California, he dedicated his life to many

airborne disciplines, but when Álvarez tried wing suiting it just stuck. The feeling of flying in the air with just his body left him feeling electrified. He gives credit to other wingsuit fliers who mentored him as he developed his own technique and skills. Over the years, he competed in several competitions, often ending up on the podium, and this domination led to a Red Bull sponsorship.

Nowadays, he tirelessly works on upcoming projects. To stay in top shape, Álvarez has a three-step training system: 1. mental training through meditation to stay calm and focused under highly stressful situations, 2. ground training and building muscle to help him maneuver with precision and accuracy in the air, 3. air training for perfect technique with live situations to sharpen his inflight senses. His training helped him to complete incredible projects like narrowly flying between the twin towers of Viña del Mar of Chile and BASE jumping from Mont Blanc.

In 2020, Álvarez set his eyes on executing a “flare” somewhere in the world. Red Bull and team found the perfect spot, Villarica, an active volcano with a large enough crater in his beautiful home country of Rucapillán, translated as “The Demon’s House.” Meanwhile, in California, the team ran through calculations to determine whether it was theoretically possible to execute a flare in the crater. The elevation, width of the crater, wind patterns, depth of the volcano, everything had to be considered. With all the calculations confirming the stunt was possible, Álvarez practiced over 200 jumps, simulating the trajectory used to execute the “flare.”

In Chile during summer, he trained around the volcano, testing the conditions and his physical capability. Around late winter, his project officially started, though there would be some days when the volcano was too active or the weather too unforgiving, making the team wait for weeks on end. Everything had to be right to get the perfect window. “I was really afraid that we were not going to find a beautiful and nice gap to make this happen,” he says.

During the live flight, Álvarez remembers the insane amount of pressure and stress he felt from risking his life, and from his team capturing videos and photos of the live event. He turned the pressure into something positive, pure focus. All he had on his mind was his speed, trajectory, and his wingsuit. And later triumph.

Álvarez recognizes that his life as an Air Force pilot, amateur surfer, and professional wingsuit flier culminates in a lifetime of preparation to accomplish such a stunt. His passion for flying pushed him to do unimaginable things, a passion he feels every time he is in the air. He has no plans of coming down any time soon.

Special thanks to Best Friends Forever, Infinity Nails, Papa’s Pizza, and Springfield Rentals for sponsoring the MINE Program.

Liz Clark’s passion for the ocean resulted in her spending 12 years living on a sailboat, seeking exotic surf spots around the world, and starting a nonprofit organization.

Patagonia-sponsored surfer Liz Clark dives under a wave.

At age 10, surfer and sailboat captain Liz Clark commenced a six-month, 5,000-mile cruise. In her memoir, Swell: A Sailing Surfer’s Voyage of Awakening, Clark explains, “I witnessed floating trash and wildlife tangled in fishing debris.” After returning from Mexico, Clark mailed the cash earned from doing her chores to Greenpeace. Her mother then gave Clark a “Save our Seas” poster and a world map to hang on her bedroom wall. Clark ended up drawing arrows on her map to show the route she hoped to sail someday. Clark says that though her family often moved the map and poster stayed with her.

According to Clark’s website, she credits “the origin of my environmental concern to my exposure to the contrasting landscapes of grave pollution and radical natural beauty in Mexico.” Two things were clear when she returned to San Diego in 1990: “I wanted to protect the natural world from human destruction and, one day, I wanted to be the captain of my own sailboat,” she says

As a result, Clark has spent 12 years (4,383 days) on a boat sailing across the world. Aside from the presence of her cat, Amelia, Clark’s love for the sea has proven enough to keep her going for such a long time. She found peace in the simplicity of boat life, something she first experienced at 7 years old when she learned how to sail. At 15, Clark’s natural athleticism led her to try surfing. Soon obsession took over. Determined to improve, she spent the majority of her free time in the water. Not long after, she started competing at a high level but also felt deeply connected. Clark says, “I love being connected to the ocean through surfing in the way that it makes me know what the tides and the moon and the wind and the elements are doing.”

For Clark, surfing allowed for constant movement, never-ending challenges, and the ever elusive search for perfection. Clark loved the ever-changing nature of the sport. “It constantly gives you that new challenge of being so present and focused,” says Clark, who won the National Scholastic Surfing Association Nationals, making her the 2002 College Women’s National Champion.

But for a young woman who had no desire of settling down, it offered her the freedom to explore the world but also to connect with others, providing a different education than what she received in a classroom. When her schooling in environmental studies at University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB) came to an end, she started to focus on the environment itself. In her book, Clark writes, “I’m disillusioned by America’s general disregard for the environment. It frustrates me that businesspeople only chase profits, while compromising our most vital resources—fresh air, clean water, and healthy soils, rivers, and oceans. Why aren’t students required to learn about the natural systems on Earth that sustain our daily lives?”

With time, her concerns of the future of the planet added worry and stress, and Clark’s surfing obsession was tainted by the realization that competitive surfing was taking away from all that surfing once gave her: a stress relief and all the fun associated with the sport. For this reason, Clark decided to shift her focus and try exploratory surfing.

As Clark rethought surfing, she started to ponder a life of freedom on the sea. One day while at work, Clark was approached by a woman in a fancy pantsuit. While serving the woman, the two quickly got acquainted, and when she found out that Clark was studying Environmental Studies at UCSB, she persuaded Clark to meet Dr. Barry Schuyler, a founder of the Environmental Studies program.

She and Dr. Schuyler talked about many things, including Dr. Schuyler’s love for sailing. As the conversation neared an end, Dr. Schuyler asked Clark what her plans were after college. Clark opened up, disclosing her dreams of sailing the world. Dr. Schuyler’s response: “You, my dear, most certainly should go. Don’t wait until life’s responsibilities anchor you.”

After that, Clark was inspired. She finished her degree at UCSB, and joined multiple sailing crews in the hopes of growing her confidence and knowledge. For four months, Clark sailed with a man who chipped away at her confidence, leaving her to believe that she was incapable of being the captain of her own boat. All that changed when she ran into Dr. Schuyler at the Santa Barbara Yacht Club. Schuyler met her with a smile, a friendly greeting and then followed up with, “I’m looking for someone to sail my boat around the world. Would you be interested?”

The coincidence was more than enough for Clark. Doubt and fear still clouded Clark’s mind, and though she felt like screaming out in joy, she told Dr. Schuyler she was unsure if she was cut out for it. Dr. Schuyler told her to stop by, and a few days later Clark gave in. Clark and Dr. Schuyler dove further into her plans, and her dream suddenly seemed within her grasp. Clark’s plans started to solidify as she started sailing Freya, until she took Freya out into the open ocean, where a big wave nearly capsized the vessel, lodging it into a sandbar. Clark told Dr. Schuyler her concerns, and he understood, offering Clark a new proposition.

If Clark could find a bigger boat, and raise money for it, Dr. Schuyler would match her and help pay for it. With the help of her father, Clark found a new boat, a Cal-40, a sailboat which Dr. Schuyler had owned, loved, and knew was seaworthy. For three years, Clark prepared for open water sailing. Clark set out to sea in October of 2005, and has since traversed over 20,000 miles.

“What I love about living on a boat is that it requires simplicity,” says Clark. “Not that it’s always simple to live on a boat, but it requires you to decipher your wants from your

Sailboat captain Liz Clark enjoys a sunset on the open sea.

needs. And you only have this limited amount of space.”

She adds, “I love that you become kind of a chain of all trades because you need to understand a little bit about a lot, and you have all of these little systems on your boat that make it kind of like a small city.”

Though Clark spent much time learning how to captain a boat, the experience became a fulfilling reminder that she could do whatever she set her mind to. She figured out how to solve problems and navigate any challenging experiences, all the while building her mental strength. Clark says, “all of us are so much stronger and more powerful than we give ourselves [credit for].”

In 2019, Clark co-founded A Ti’A Matairea, a French Polynesian non-profit organization, dedicated to supporting classroom marine conservation lessons and after-school experiential education programs. According to 11th Hour Racing, “A Ti’a Matairea’s classroom program teaches students about local coral reef ecosystems and the Tahitian preservation method called ‘Rahui.’ Their after-school program serves

under-resourced youth with hands-on outdoor excursions to nurture an appreciation for biodiversity and how local species are connected to their Tahitian heritage. Cultivating a deep understanding of the island’s ecosystems has a long-term positive impact by fostering the environmental protectors of the future. Students graduate as a ‘Tamarii no Te Natura’ or ‘Ambassador of Biodiversity.’”

Clark is currently working with A Ti’a Marairea on the Marine Protected Areas Project. The main goal is to relaunch traditional fishing protections and create marine protected areas, striving to create healthy ecosystems that will allow fishing communities to continue their way of life. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the traditional fishing protection, Rahui, is “in essence, an area of land or water with a temporary limit on collecting a resource, such as a particular fish or fruit. In time, once the resource has replenished, the Rahui is lifted.”

Clark’s journey, filled with determination, passion, and dedication, is the path of a young woman working for what she wants and overcoming all the roadblocks along the way. Her story also includes making a seemingly impossible dream come true and making a difference in the world. As Clark continues to work towards positive change, she has learned to embrace unruly waters and let the ocean guide her.

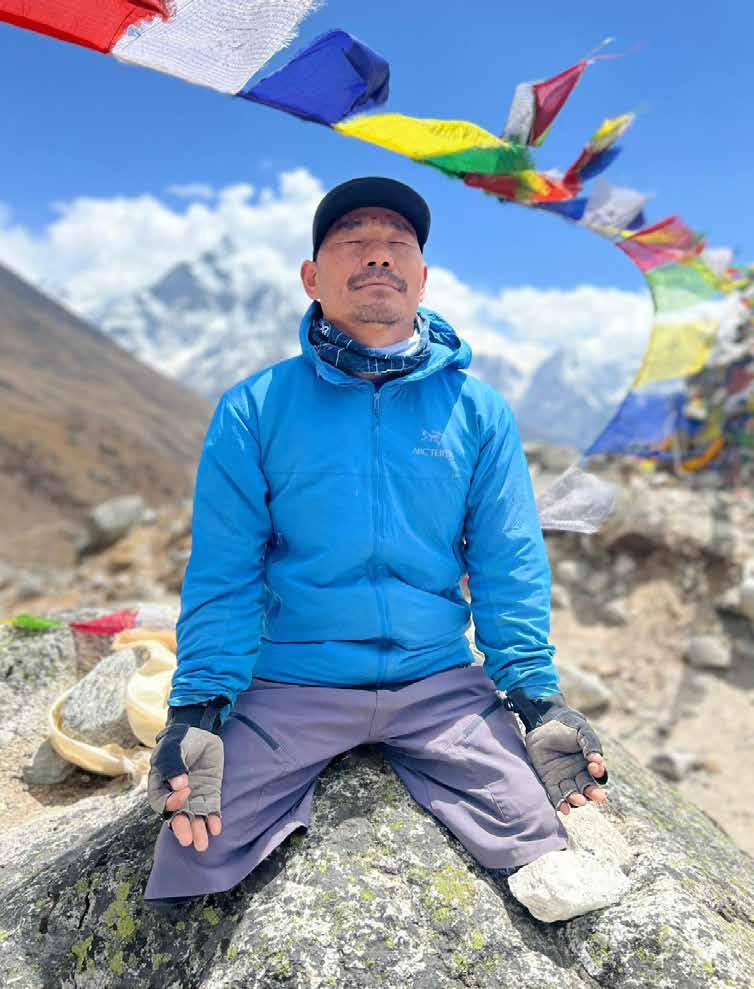

Mount Everest is not only the tallest mountain in the world but for many it represents the peak of mountaineering as a whole. It is a month-long journey through exhausting climbs, unpredictable weather, and extreme cold. With temperatures of -19 F° on average, boiling water can freeze solid in minutes and slippery terrain causes a number of deaths every year. Climbing Mount Everest proves challenging for even the most experienced climbers. Hari Budha Magar’s summit was even more intense. Magar lost both of his legs serving in the British Army, but that did nothing to slow down his spirited personality. As a result, he became the first above-the-knee double amputee to summit Everest in 2023.

Magar had a humble beginning, growing up in a small village in western Nepal called Miru, situated in the foothills of the Himalayas. Magar spent his childhood looking up to Everest in awe, dreaming of one day summiting the tallest mountain in the world. “Nepal is known for three regions, Mount Everest, Gurkhas, and the home of Buddha. I’m related to all three,” he says.

Growing up on the outskirts of Nepal was a struggle for Magar from the very beginning. He came into the world in a cow shed almost 9,000 feet above sea level. “There weren’t any hospitals in the village, so that’s just how babies used to

be born,” says Magar.

The closest school was 45 minutes away, a trek Magar had to make barefoot every day across wooden footbridges and swollen rivers. The school did not have access to pen or paper, so Magar had to learn to write on wood with chalk. He never thought of this as an educational deficiency. “I didn’t know any different lifestyle,” he says. “I only knew of where I was.”

He was later forced into an arranged marriage when he was 11, a common tradition in Nepal, although one he was not happy with. Magar had little say in how he wanted to live until he was 17, when he set his eyes on the British Army.

Becoming a member of the Royal Gurkha Rifles is a tremendous honor that thousands of Nepalese apply for every year, and in 1998 Magar earned a spot. His father originally dreamed of joining the military, but as the only son in his family, he had to stay with the farm and give up on his dream. Magar’s father wanted to provide a different experience for his children.

Magar found that Gurkha life represented a stark contrast from his small village in the Himalayas, where people were closed off from most of the world. In a flash, Magar’s rustic and secluded life quickly turned into a confusing one filled

with unfamiliar technology and customs where efficiency was everything. Although far outside his comfort zone, he soon fell in love with military life, serving in the roles of sniper, covert surveillance, and in a medical office.

The Gurkha was where Magar originally learned the value of adapting to his surroundings, quickly mastering the fastpaced environment of the British Army. Although it seemed miniscule at the time, Magar’s resilience eventually saved him. Rising to the rank of corporal, he began serving in Afghanistan. During a patrol in 2010, Magar stepped on an improvised explosive device while going to look in an old well. “We were just walking along and something went bang,” he says. “In that millisecond my life changed.”

Magar was flown to the United Kingdom to undergo two emergency operations and both of his legs were amputated above the knee. His life was flipped upside down as everyday tasks became massive obstacles. After 26 years of service, he was honorably discharged.

Recovering from his injury, Magar felt completely lost. Not only were his skills from the military now unusable, Nepal’s culture around disabilities made finding purpose incredibly difficult. He says, “in those remote villages in Nepal many people believe that once you’re disabled you can’t do anything. So disabled people are a burden for the earth.”

The disability made finding a job extremely arduous, and going back to a life of farming seemed unfathomable. In less than a month, it seemed as though all of Magar’s paths were completely cut off, leaving him without direction. He slipped into a depression and turned to alcohol to dull his pain and emotions.

“I thought my life was finished,” he says. “I thought the rest of my life would be in a wheelchair with people taking care of me… I saw no point in living. I thought about killing myself. I thought of jumping off of a railroad bridge, hanging myself, even crashing myself in a car. My hands shook and I knew that by drinking so much I would die soon.”

After a year-long struggle through rehab, Magar had a revelation. His addiction would inevitably lead to one choice: succumb to alcohol abuse or stay with his family. Magar had a three-year-old son at the time, and decided he could not allow him to grow up on his own. In an attempt to set himself straight, he began looking for a new purpose.

Magar decided to live his life the way he was always afraid to, purposely taking up activities he always considered too difficult or unrealistic. First on his list: skydiving. After falling from 15,000 feet and landing safely on the ground, Magar was granted another epiphany–his injury was not a setback,

but an inspiration, a reason to unlock his true potential both physically and mentally. Taking on dozens of activities that pushed him to his limits, including rock climbing, skiing, rugby, and basketball, Magar decided to take on the tallest peak in the world.

He began training hard for Everest, compiling gear and gathering crew members. As the date of the ascent grew closer, it seemed as though Magar’s dream was finally in his grasp, but in 2017 the Supreme Court of Nepal put it all to a halt. That year, they banned all solo, amputee, and visually impaired climbers from attempting a summit in an effort to reduce accidents. This was devastating and infuriating to Magar, who expected Nepal to be proud of him. He decided to take matters into his own hand and went to the media, declaring Nepal’s decision to be discriminatory and a defamation of his country’s image, saying, “you can’t take someone’s rights away because they aren’t able to do [the same things]. We can’t just ban people from summiting because they have a different age, race, or religion. We can’t discriminate.”

Magar soon filed for an official court case, telling the world that he would summit either way, whether he was banned or not. In 2018, through the efforts of both Magar and the Nepal National Federation of the Disabled, the Supreme Court of Nepal overturned the ban, and Magar resumed planning his summit attempt.

During the ascent, Magar feared they would have to go back after discovering a leak in his oxygen tank. Magar says, “the guys sent my oxygen and they said it was full. But it leaked. It was empty already. For about 20 minutes I was without oxygen at very high altitude. My hands tingled. I felt that I had no energy. I thought we would all die.”

His fear increased after seeing two bodies being carried off during the ascent, but Magar was too close to back down. Shortly thereafter he became the first double-leg amputee to summit. His achievement felt much bigger than he could have dreamed, as he soon helped others to face their own challenges. “When I climb my mountain, I hope to inspire other people to climb their own mountain, whatever that mountain is, whether [it is] getting a job, getting married, getting a promotion, or whatever adversity they are going through in their life,” says Magar.

Magar is now a hero in Nepal, inspiring thousands to redefine their own limits. He strongly believes “confidence is everything in life. You don’t need to be super smart, you don’t need to be super intelligent, and you don’t need to be super fit. But if you have a positive mindset and you work hard [nothing else matters].”

Sasha DiGiulian uses the successes of her climbing career for political lobbying to help protect the environment.

Amanda Arch

On a brisk October morning in 2011 Sasha DiGiulian began her ascent of the Pure Imagination route in Red River Gorge, Kentucky. Should she complete the 9a climb, DiGiulian would become the third woman, and the first ever American woman to do so. Having completed her first 8c climb just seven months prior, the leap to a 9a route was almost unheard of. Though the climb is just 80 feet, its intense overhang and three crux sections make it an extremely difficult route with -

rapher and onlooker Keith Ladzinski was instantly impressed by the raw talent scaling the wall. By the time she completed

grew up, rock climbing was a fairly unpopular sport. With no prior experience or outside inspiration, a 6-year-old DiGiulian fell in love with it during her brother’s birthday party in a Sportrock indoor climbing gym in her hometown of Alexandria, Virginia. Despite being the youngest, and only female amongst the group, DiGiulian quickly left her sibling and his friends in the dust as she scaled the vertical handholds lining the walls. The thrill of hanging above the ground with her fate held in the tips of her fingers brought DiGiulian to life. She was forever changed. Even after the party was well finished and she had returned home, she sought any and every opportunity to climb whatever she could.

To nurture her newfound obsession, DiGiulian’s parents quickly signed the young athlete up for a junior climbing team at Sportrock, where she learned the skills necessary to take her passion to the next level. Within just a year, she began competitively climbing with some of the most talented kids in the area. In less than 10 years, she started setting records.

Over 25 years after her first experience, DiGiulian is still climbing, achieving new goals and setting records annually. DiGiulian has claimed the title of three-time US National Champion, as well as silver medalist in the Bouldering World Championship. With her ever-expanding list of titles and over 30 first-female ascents of 5.14 and harder, she is considered one of the top female climbers in the world.

DiGiulian proves extremely talented, but her passion also forced her to get outside and travel the globe, taking her to over 50 countries throughout her career. She appreciates that climbing is a mind-body sport, which pushes her to have strict control over both the physical and mental control demanded of each ascent.

While DiGiulian quickly earned herself the title of one of the best female climbers ever, her career has not been without

its share of hardships. Towards the end of 2017, DiGiulian began noticing some pain in her hips. Assuming she had torn her labrums and knowing that many athletes continue to work through the injury, DiGiulian kept climbing. However, the pain persisted and worsened over the next two years, and by March of 2020 she could barely sleep through the night due to the intense discomfort. Seeing as she was just finishing up a string of European climbs and preparing to make some ascents of Mexico’s El Gigante rock face, DiGiulian planned a trip to the emergency room, hoping to get a cortisone shot to dull the pain. During an assessment MRI, DiGiulian received devastating news. Not only had the athlete torn both of her labrums, but she had a terrible case of hip dysplasia.

The young climber sought the advice of many medical professionals, including a trio of surgeons who all agreed upon the fact that the cartilage damage that had been dealt in DiGiulian’s hips over the past few years was severe enough to warrant a new set of hips unless addressed immediately. Despite this information, DiGiulian was still cleared to finish her upcoming expedition in Mexico, as long as she returned to the United States to have her hips fixed afterwards. However, the Mexico trip was completely derailed when DiGiulian’s climbing partner and friend Nolan Smythe fell to his death on the 14th pitch of El Gigante’s Logical Progression route two days before DiGiulian’s planned arrival date. Smythe had been making his ascent of the route, fixing lines for the expedition photographer and his girlfriend, Savannah Cummins, when the ledge he was standing on crumbled beneath him, the sharp edges of rock severing his rope as he fell over 1,500 feet to his death. “It was a crazy, horrible, freak accident, theful and experienced of climbers like Nolan,” says DiGiulian. Less than 24 hours after his passing, DiGiulian, Cummins and members of the Smythe family were flown down to help

grueling task of recovering the body of her beloved climbing mate, DiGiulian flew back home -

Giulian underwent an eight-hour open procedure in which her labrums were stitched and the heads of her femurs were -

structed using six-inch screws. This operation also required all of her lower abdominal muscles to be removed, and then individually stitched back into place.

In February of the next year, DiGiulian had her final op-

eration, which removed all of the hardware from previous surgeries. This intensive series of procedures left DiGiulian in a body that was completely different from the one she had known just six months prior. Where there was once a toned, muscular, fit young woman with a sky high attitude and love for climbing, there was now a woman with a healing body and the fear that she would never be able to indulge in her passions again. Missing a crucial part of her identity, DiGiulian redefined her relationship with her self image as not just a climber but a woman who is incredibly passionate about the outdoors. Her journey eventually helped her develop a voice for political action. “It’s given me a voice to speak up for things beyond climbing and beyond sports that matter,” she says.

With climate change posing an ever-growing threat to outdoor sports as a whole, many outdoor athletes are seizing opportunities to speak out and demand political action. In 2016, DiGiulian began learning about Congress, specifically the act of political lobbying. As a newly graduated Columbia University student, she was invited to join the American Alpine Club (AAC), an organization rooted in climbing education and advocacy. DiGiulian described lobbying with the AAC as “an incredibly powerful experience,” where she faced a domain that was teeming with politicians. DiGiulian shares many of the AAC’s core values, striving to ensure the protection, cleanliness, and accessibility of natural spaces. Her love for outdoor sports and her climbing background only strengthened her connection to these issues.

DiGiulian was not alone in her lobbying efforts. In May of 2017, the AAC and the Access Fund, an organization which protects outdoor climbing spaces, pooled together a group of climbers to address the American Senate in Washington D.C. This group consisted of some of the best current climbers, including DiGiulian, record-setting climber Tommy Caldwell, and Free Solo star Alex Honnold. The group addressed a myriad of issues revolving around climate change, most of which focused on the importance of protecting and improving outdoor spaces for both recreational sports and enjoyment and for the economical and ecological benefits they hold.

As climbers, DiGiulian, Caldwell and Honnold acknowledge the fact that protecting natural areas could serve as an extreme economic benefit, as well as open the door for the creation of outdoor focused jobs. Their ultimate goal was to convince the American Senate to stick with the Antiquities Act, which was under review by then newly elected President Donald Trump.

Originally signed in June of 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt, the Antiquities Act was the first official U.S. law designed to preserve and protect natural resources and lands of scientific or historic importance. The act has been used

Alex Grymanis / Red Bull Content Pool

Alex Grymanis / Red Bull Content Pool

over 150 times by 16 different United States presidents to protect federal lands from exploitation, further expanding national monuments and parks, and protecting culturally and historically important lands which have been sought after for their abundance of resources.

Any review of this act might have endangered millions of acres of natural territory, including several National Park territories that were previously protected. Digiulian, Honnold, and Caldwell all depend on natural areas for their careers and completely support the protection of public lands. “What I cherish about the outdoors is what makes America so unique to people globally: our public lands,” DiGiulian told Outside magazine in 2019.

DiGiulian believes in the power that the climbing community holds to protect federal lands, which have held a special place in her heart. At the age of 9, DiGiulian and her mother drove to Hound Ears Club in Boone, North Carolina, where they escaped the cold of the night in a cozy log cabin. DiGiulian’s mother surprised her with her first ever Triple-Crown event, a climbing convention and competition in which climbers from across the country could showcase their skills as they navigated ten boulder problems over the course of a single day. While the event took place in three separate land areas, the main hub of the competition, Hound Ears, is protected land, making the event all the more special as the area is only opened up to climbers once or twice annually for them to celebrate their sport. Through her success and ever growing platform, DiGulian hopes to protect the lands which have