THE DAVID M. SOLINGER COLLECTION 14 NOVEMBER 2022 N11087 NEW YORK

Cover Lot 10, Willem de Kooning, Collage (detail). Art © 2022 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Back cover Lot 8, Alberto Giacometti, Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau) Art © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris This page Lot 8, Alberto Giacometti, Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau) Art © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

IMPORTANT NOTICE

Lot 19, Pablo Picasso, Femme dans un fauteuil Art © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PROPERTY IN THIS SALE, PLEASE VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/ N11087 AUCTION IN NEW YORK 14 NOVEMBER 2022 5:30 PM 1334 York Avenue New York, NY 10021 +1 212 606 7000 sothebys.com FOLLOW US @SOTHEBYS #SOTHEBYSSOLINGER Friday 4 November 10 AM–5 PM Saturday 5 November 10 AM–5 PM Sunday 6 November 1 PM–5 PM Monday 7 November 10 AM–5 PM Tuesday 8 November 10 AM–5 PM Wednesday 9 November 10 AM–5 PM Thursday 10 November 10 AM–5 PM Friday 11 November 10 AM–5 PM Saturday 12 November 10 AM–5 PM Sunday 13 November 1 PM–5 PM Monday 14 November 10 AM–1 PM ALL EXHIBITIONS FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC NEW YORK | 14 NOVEMBER 2022

Parties with a direct or indirect interest in the lots in this sale may be bidding on one or more lots. Please refer to the Conditions of Business for Buyers for more information concerning Interested Parties.

SPECIALISTS

BROOKE LAMPLEY

EVP, Chairman & Worldwide Head of Sales Global Fine Art Brooke.Lampley@sothebys.com

HELENA NEWMAN

Chairman, Sotheby’s Europe Worldwide Head, Impressionist & Modern Art Helena.Newman@sothebys.com

LISA DENNISON EVP, Chairman, Americas Lisa.Dennison@sothebys.com

GRÉGOIRE BILLAULT SVP, Chairman Contemporary Art Grégoire.Billault@sothebys.com

DAVID GALPERIN SVP, Head of Contemporary Art, Americas; Co-Head, Marquee Sales, New York David.Galperin@sothebys.com

JULIAN DAWES

SVP, Head of Impressionist & Modern Art, Americas; Head of Modern Art Evening Sale, New York Julian.Dawes@sothebys.com

SCOTT NIICHEL Head of Auctions Modern & Contemporary Art Americas Scott.Niichel@sothebys.com

KELSEY LEONARD VP, Specialist; Head of Contemporary Art Evening Sale, New York Kelsey.Leonard@sothebys.com

EDITH EUSTIS

VP, Specialist, Head of Research Impressionist & Modern Art Edith.Eustis@sothebys.com

SARA LAND Associate Specialist Impressionist & Modern Art Sara.Land@sothebys.com

ENQUIRIES

BIDS DEPARTMENT +1 212 606 7414 fax +1 212 606 7016 bids.newyork@sothebys.com

Telephone bid requests should be received 24 hours prior to the sale. This service is offered for lots with a low estimate of $5,000 and above.

SALE ADMINISTRATOR

Jon Boos Jonathan.Boos@sothebys.com

POST SALE SERVICES

Cara Mitchell Post Sale Manager Cara.Mitchell@sothebys.com +1 212-606-7444

FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS CALL +1 212 606 7000 USA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 for UK & Europe

FOR CONDITION REPORTS CONTACT

Kelsey Macpherson Cataloguer

Modern & Contemporary Art Kelsey.Macpherson@sothebys.com

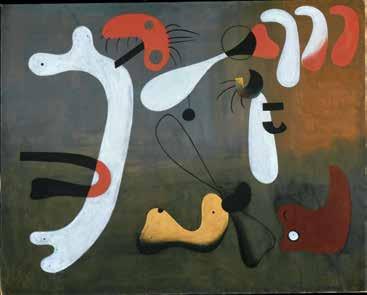

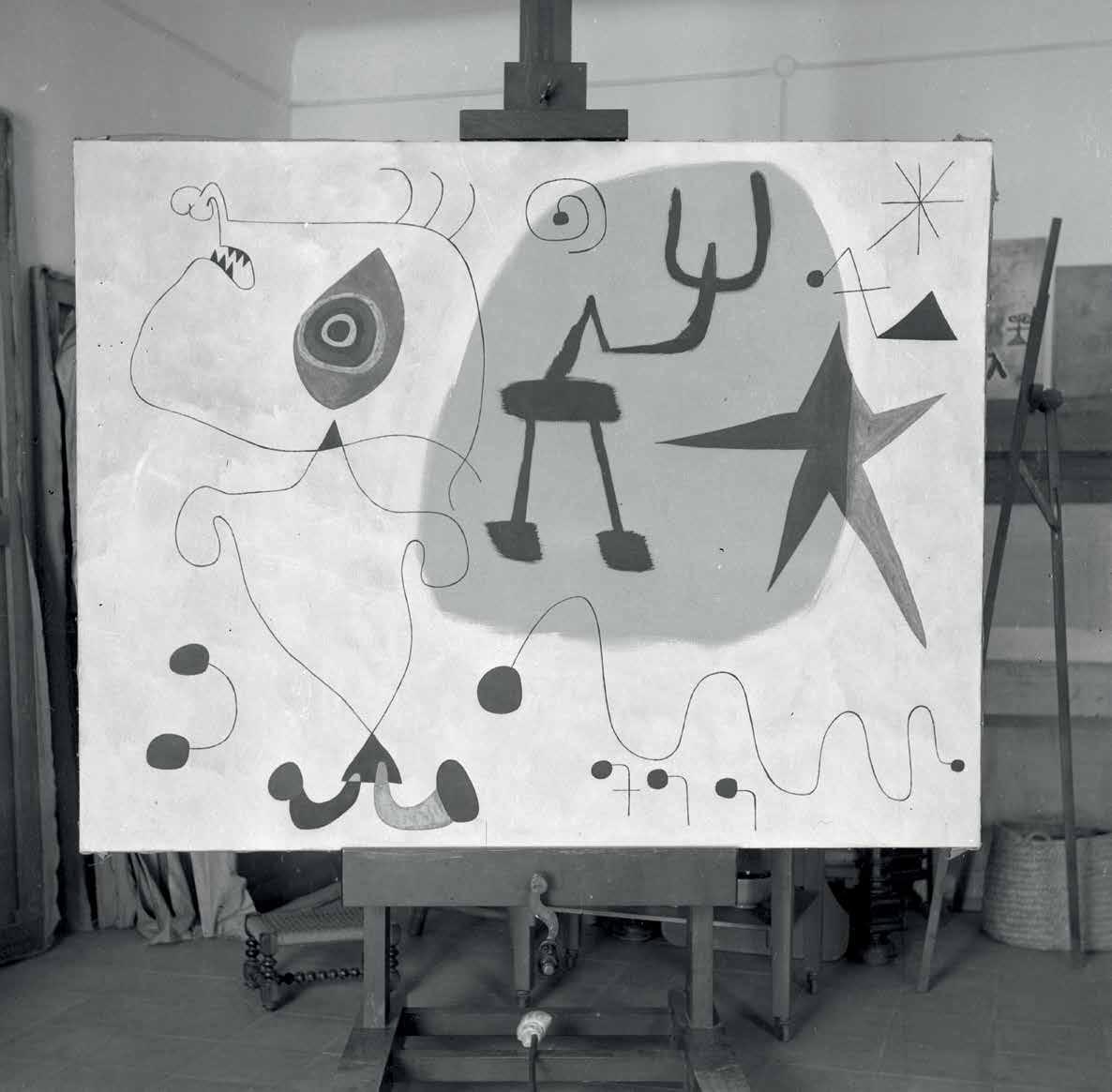

Lot 4, Joan Miró, Femme, étoiles (detail)

CONTENTS

11–25

THE DAVID M. SOLINGER COLLECTION BY JOHN ELDERFIELD 26–39

DAVID M. SOLINGER: A VISION FOR A NEW GENERATION 40–233

THE DAVID M. SOLINGER COLLECTION EVENING SALE, NEW YORK 234–283

MODERN ART DAY SALE, NEW YORK 284–291

ARTS OF AFRICA, OCEANIA, AND THE AMERICAS, NEW YORK 292–301

A LEGACY OF PHILANTHROPY: A SELECTION OF WORKS FROM THE DAVID M. SOLINGER COLLECTION GIFTED TO MUSEUMS AND INSTITUTIONS

HOW TO BID

CONDITIONS OF BUSINESS FOR BUYERS IN NEW YORK AUCTIONS 308 BUYING AT AUCTION

INFORMATION ON SALES AND USE TAX IMPORTANT NOTICES

INDEX OF ARTISTS

302

303

310

312

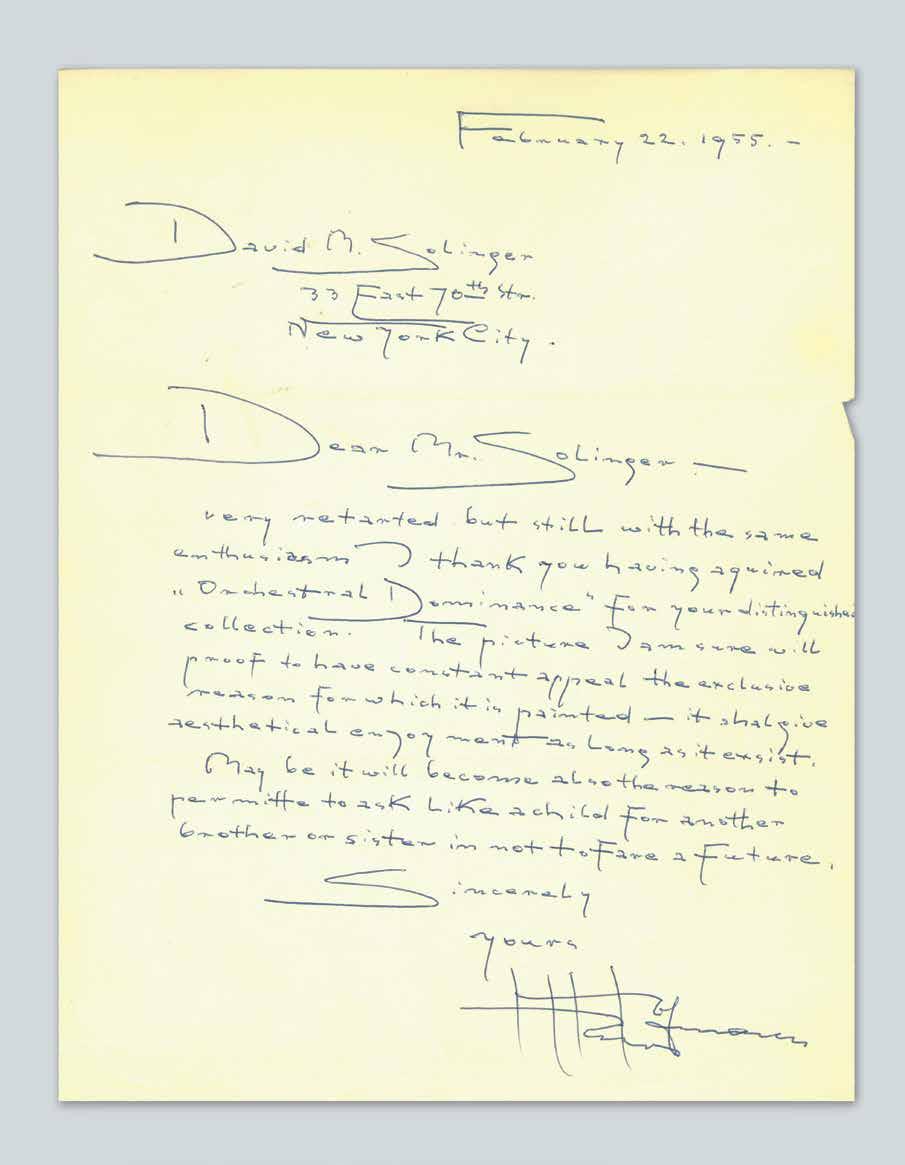

Introducing an exhibition of The David M. Solinger Collection in 2002, art historian Robert Rosenblum began by distinguishing four kinds of private collections: one, an anthology of big names like a miniature museum; one, a collection of contemporary art that attempted to be as up-to-date as possible; one that was simply quirky, the product purely of personal enthusiasm, indifferent to differences of good and bad; and one embedded in a passion for a particular moment in history. Rosenblum correctly insisted that David Solinger’s collection was of this fourth kind. I will speak here mainly on this subject; but first I want to mention a fifth kind: collections put together by artists.

Solinger studied painting at the Art Students League in New York City prior to buying his first painting, in 1948—a modest canvas by the Hawaiian-American Reuben Tam at the Halpern Gallery in New York. He continued to paint even as his law practice

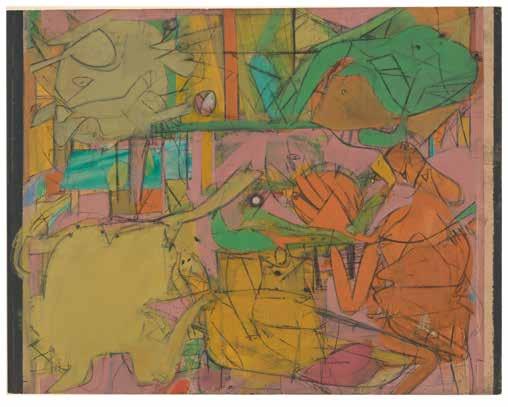

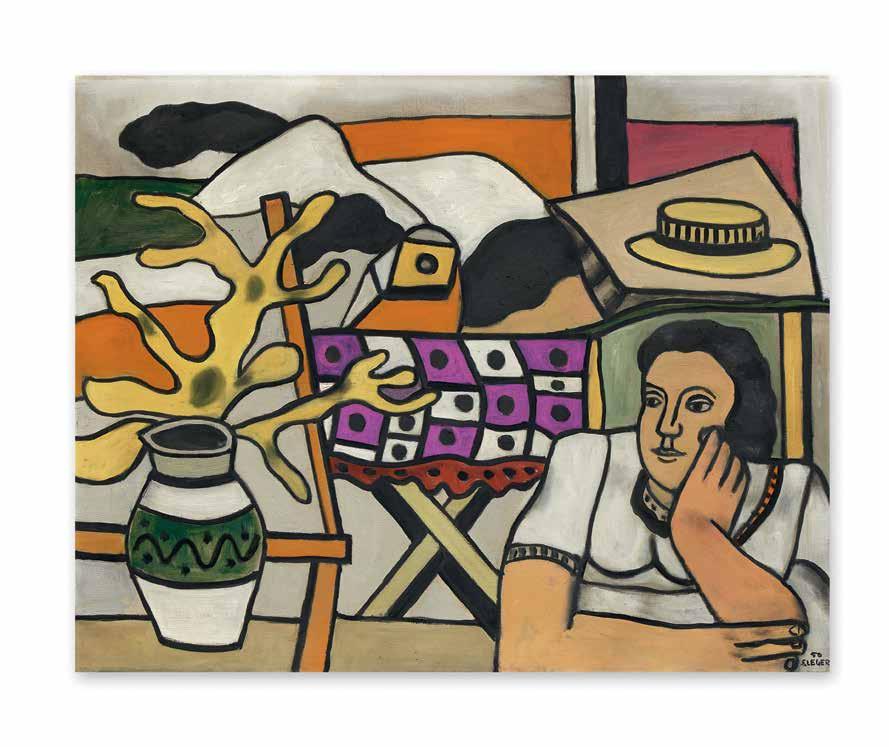

Lot 19, Pablo Picasso, Femme dans un fauteuil; Lot 10, Willem de Kooning, Collage; Lot 11, Fernand Leger, Une femme brune et une plante jaune Photo © Visko Hatfield 11

JOHN ELDERFIELD © 2022

increased and as he continued to collect. Two great late-nineteenth-century painters, Gustave Caillebotte and Edgar Degas, put together extraordinary collections. Solinger was not in their league as either painter or collector, but he brought his amateur painter’s eye to his collecting. The great German Renaissance painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer said that only artists can judge art; for all others it is a foreign language. If that is true, then it is a foreign language that has to be learned by those who are not artists, which means that they too should be spending more time in front of paintings than reading books about them.

I do not doubt for a moment that Solinger read as well as looked; his collection speaks of his knowledge. But it speaks even more of the trust he developed in his judgments based upon his own, continual looking at works of art. As early as 1956, he told the Cornell Daily Sun that he was dedicating

six hours a week, roughly a full workday, to looking at paintings. And some twenty years later, in 1977, he told Whitney Museum of American Art curator Paul Cummings that to maintain your level of connoisseurship you have to see a lot of pictures.

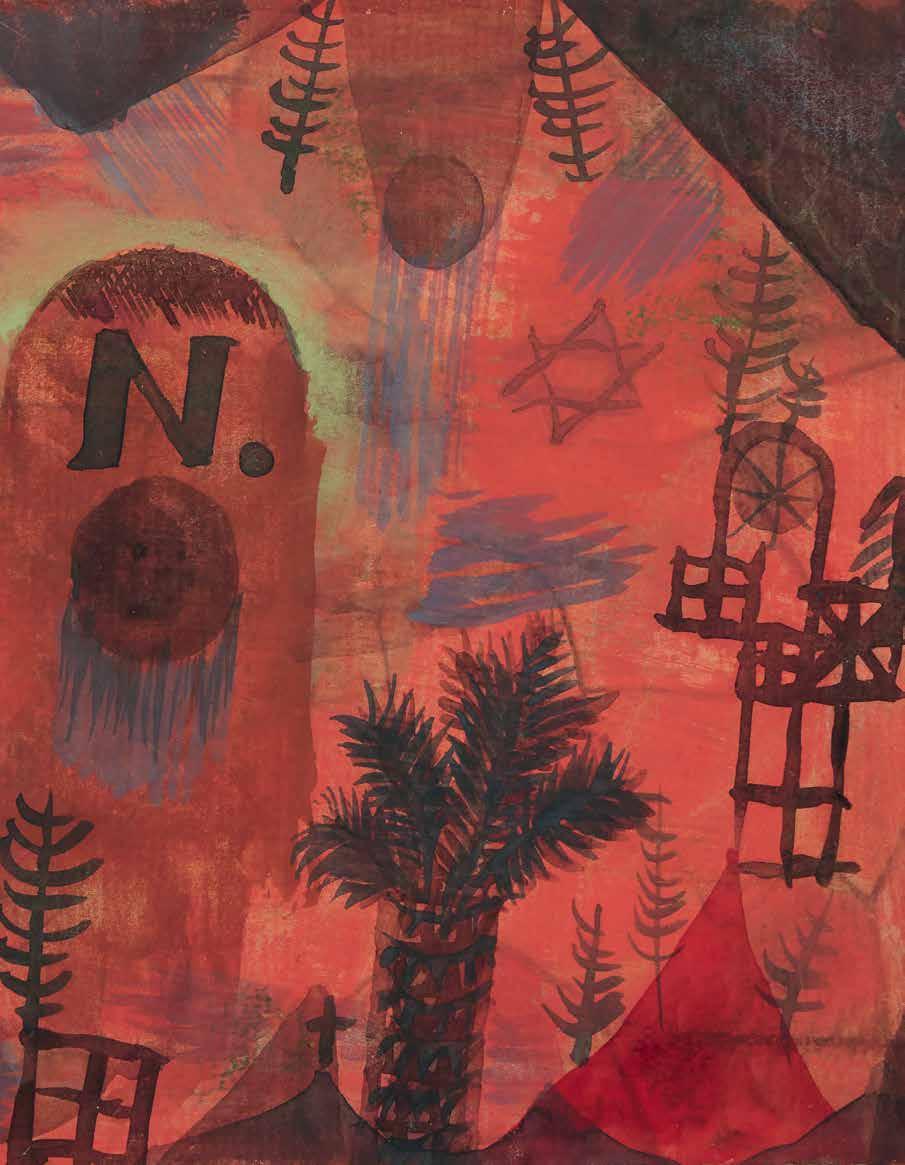

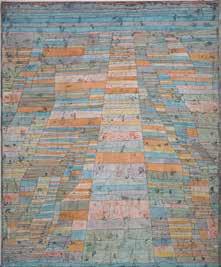

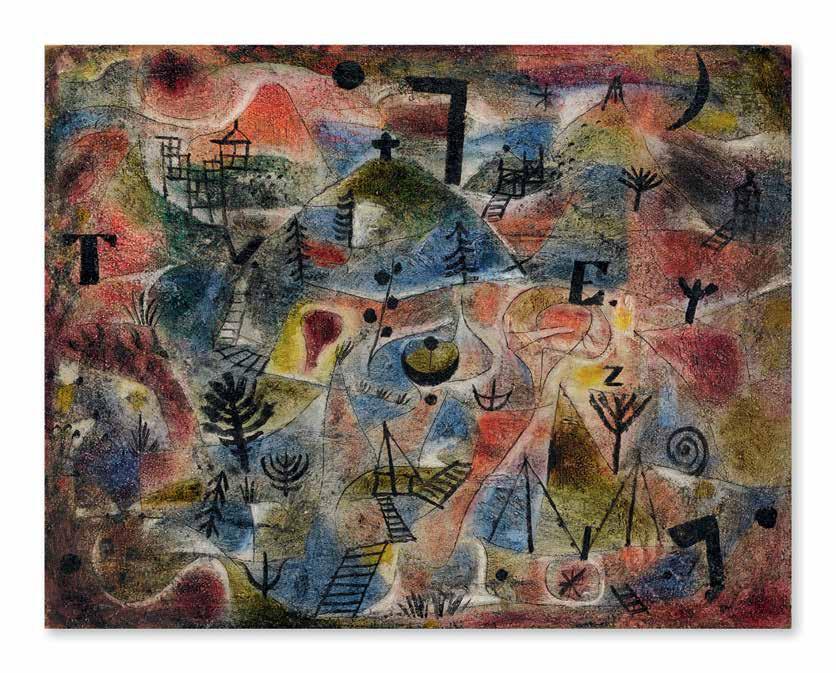

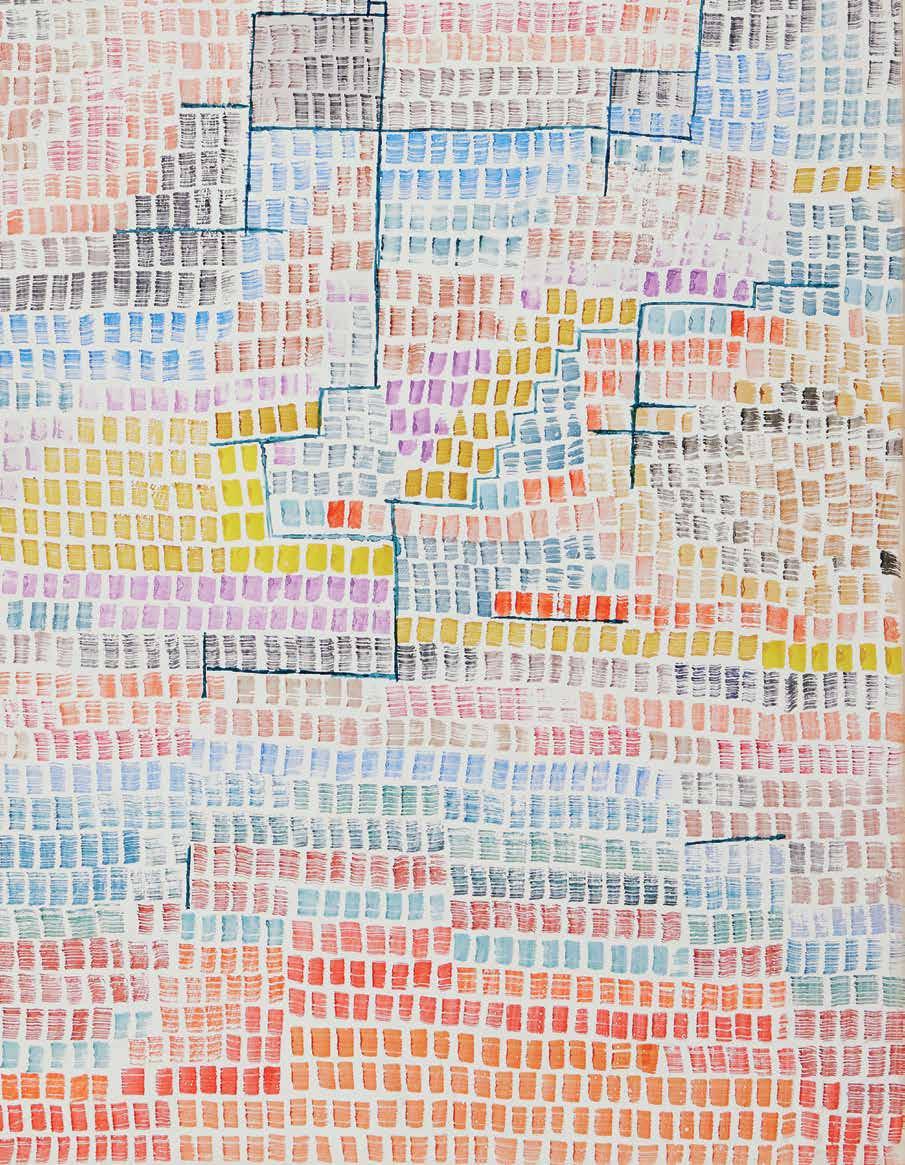

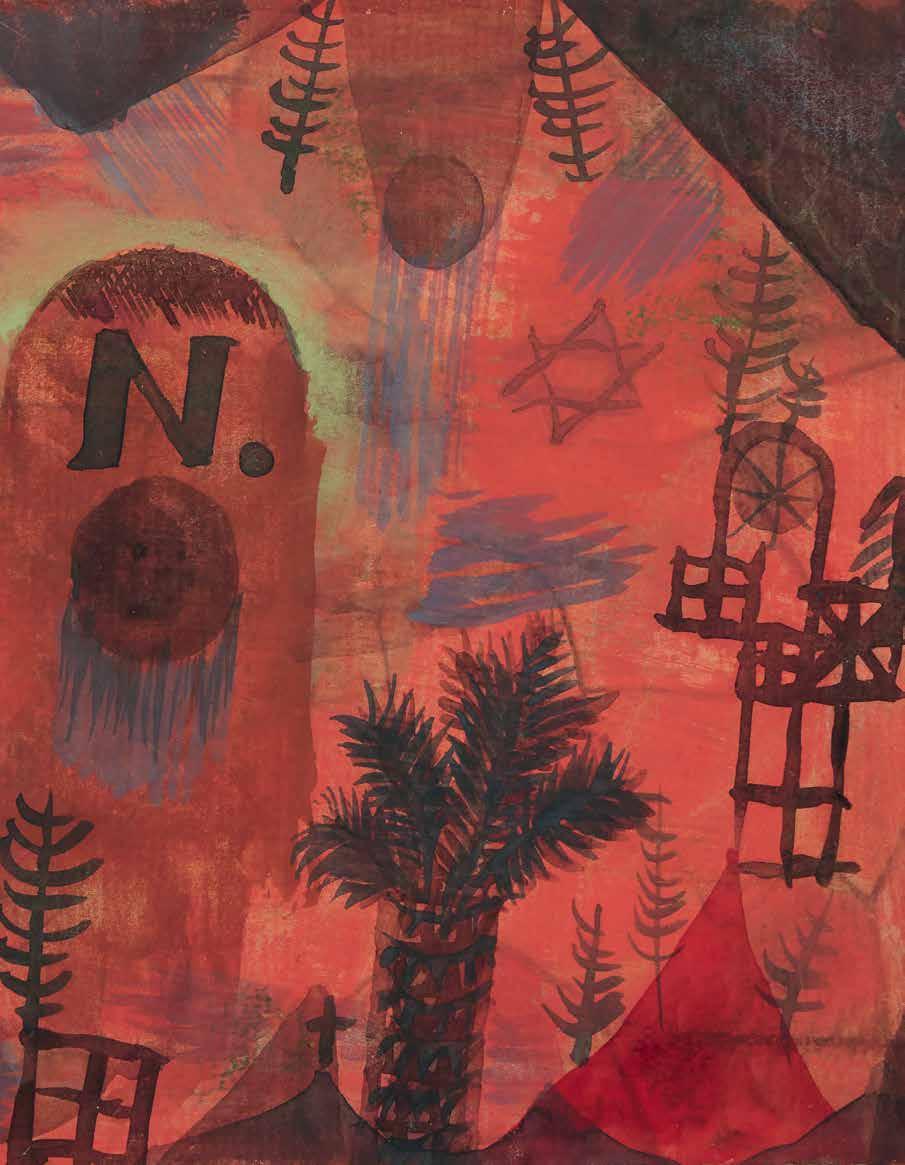

Evidence of his trust in his own connoisseurship may be quantified: fewer than a half-dozen of the twenty-three works recorded in this catalogue had any prior reputation that may have influenced Solinger to acquire them, except that they came from trustworthy dealers. Three of his four works by Paul Klee had already been shown in early exhibitions, but the first that he purchased, from the Galerie Rosengart in Lucerne in 1951, had no prior public history. One of the two pictures by Joan Miró he bought that same year from the Galerie Maeght in Paris, had been published six years earlier in a short essay by the poet Tristan Tzara in Cahiers d’Art. And the final

1963 acquisition in this group of works, the Jean Arp sculpture of 1936, had been in the celebrated collection of David Thompson.

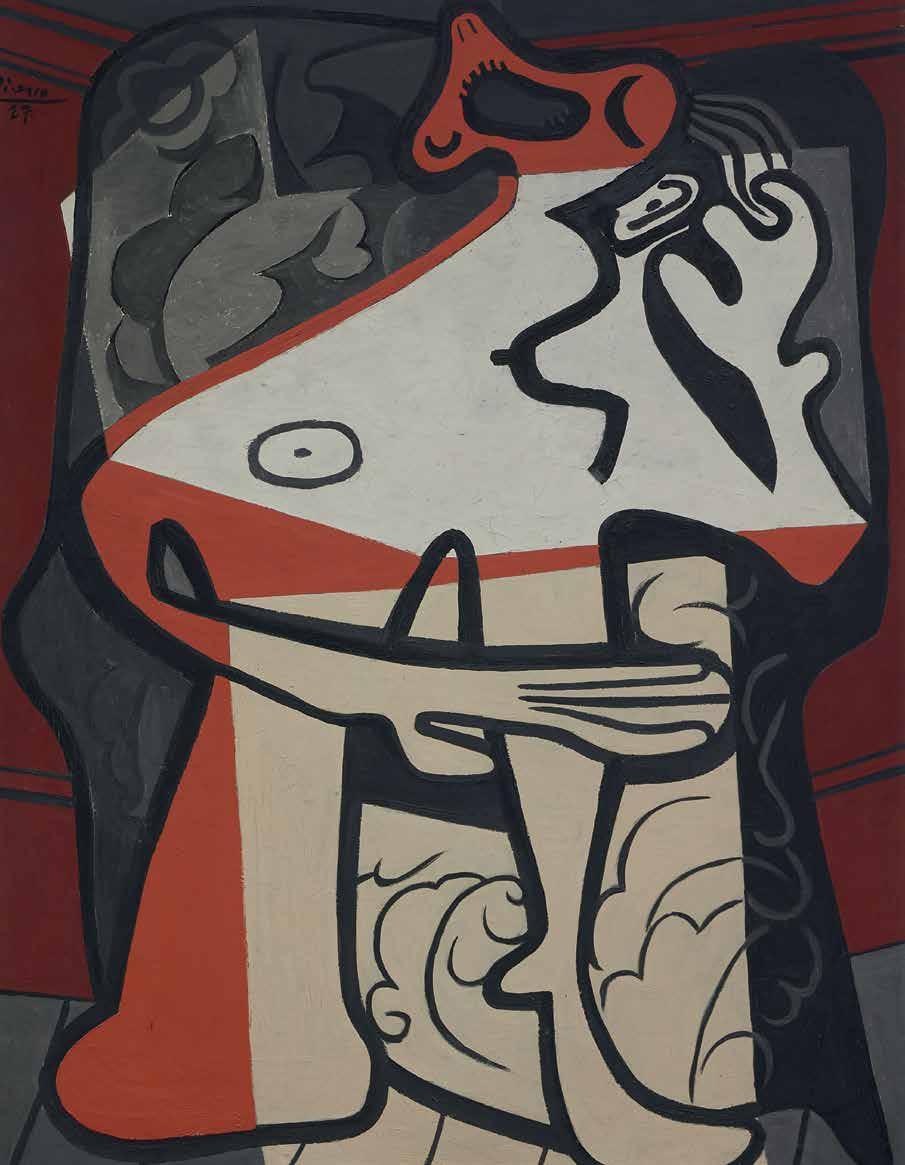

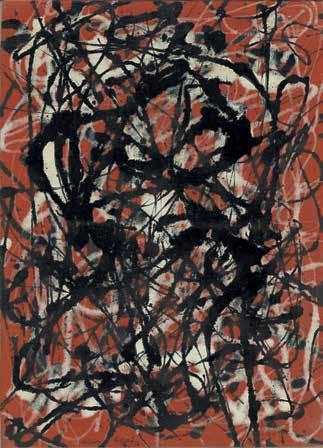

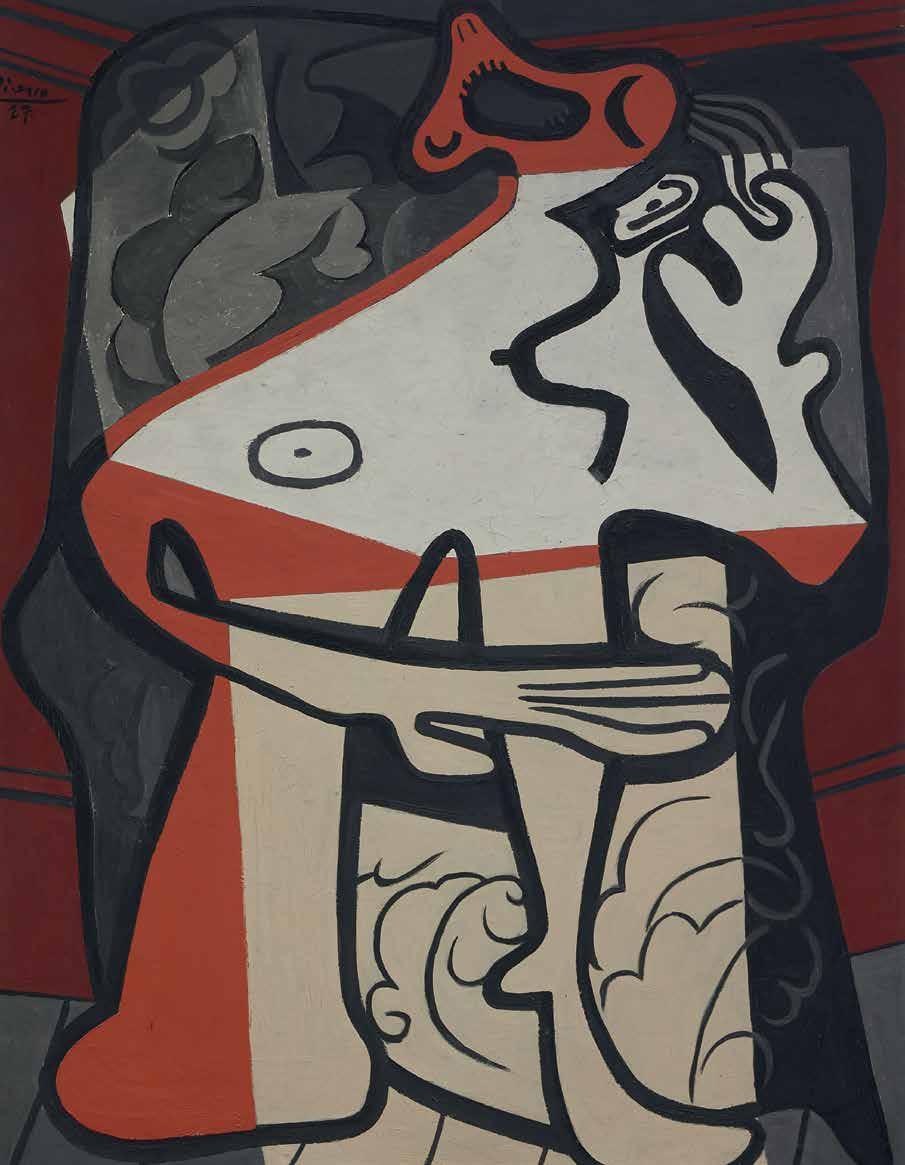

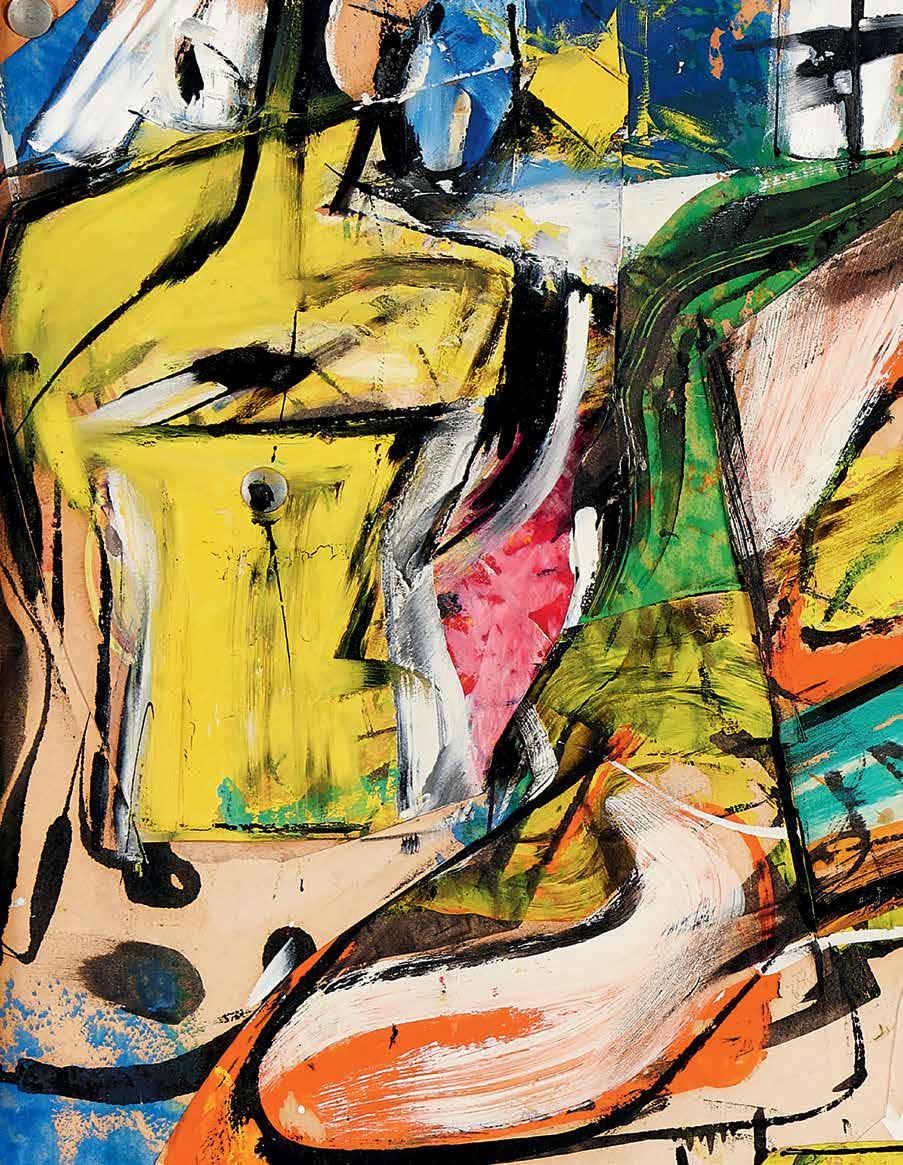

Solinger was not yet interested in art when the great 1927 canvas by Pablo Picasso, which he acquired in 1958, had been exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art some twenty years earlier, but it is likely that Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who sold it to him, told him of that fact. The unique 1950 Willem de Kooning collage he bought from Sidney Janis in 1952 had been illustrated the previous year in

Thomas B. Hess’s book, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase, however, Solinger had been looking at de Koonings since the artist’s first show at New York’s Charles Egan Gallery in 1948. In the main, then, he trusted solely his own judgment and that of the some-dozen dealers from whom he bought these two dozen works. Doing so, he was ahead of his time in his attraction to works by painters who would subsequently be acknowledged as of pivotal importance to mid-century art, or influential upon art of that period.

12 SOTHEBY’S

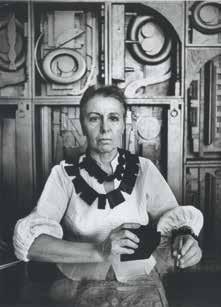

David M. Solinger (center) with Alan H. Temple (left) and B.H. Friedman (right), members of the Whitney Capaign Planning and Building Committees, circa 1960s

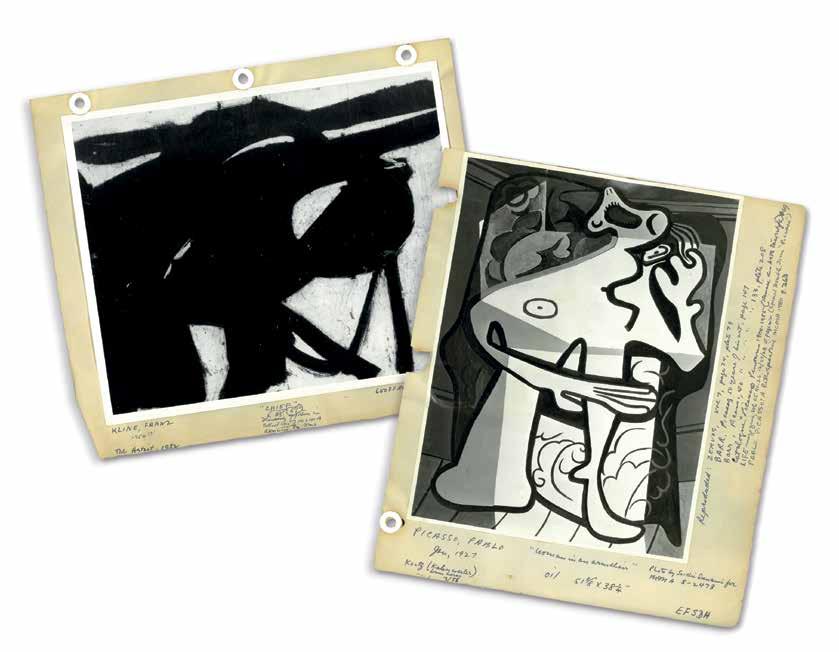

Franz Kline, Study for Chief (Modern Day Auction); Louise Nevelson, Black Disclosure #1 (Modern Day Auction). Lot 8, Alberto Giacometti, Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau)

Photo © Visko Hatfield

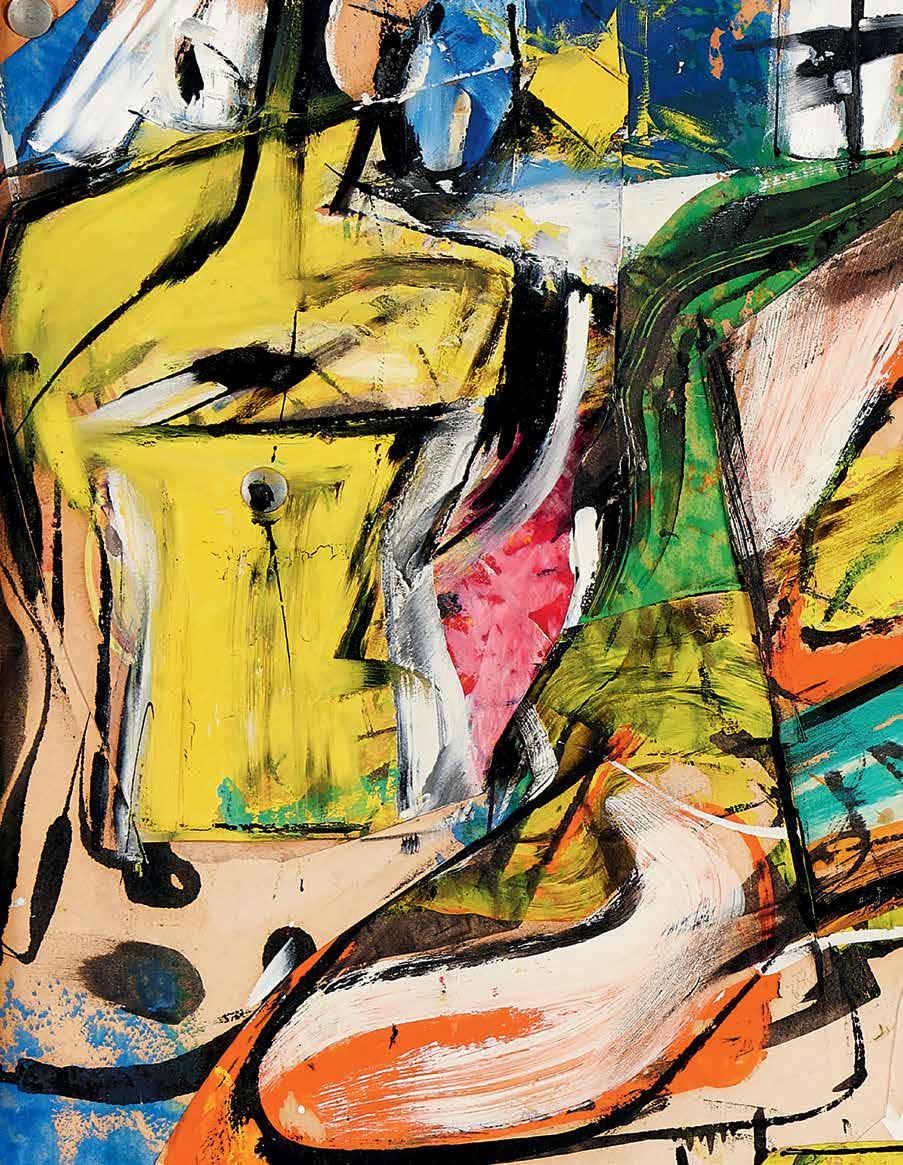

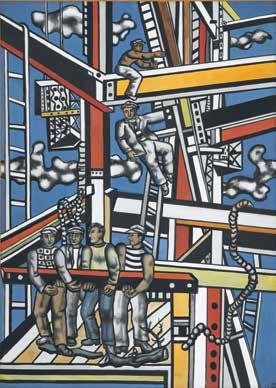

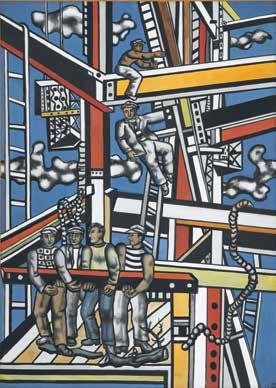

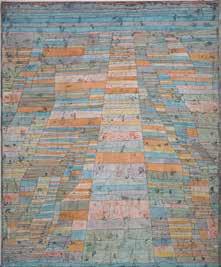

It is a fascinating coincidence that it was in the same year that he bought his first, hardly controversial canvas that he visited the Charles Egan Gallery and was so overwhelmed by de Kooning’s utterly unfamiliar paintings that he long remembered having stayed there the whole day. It seems fair to say that the experience shaped what his collection would come to comprise: in the main, a mid-century collection of works of the 1940s and 1950s. Only eight of the twentythree works recorded here were made prior to this: the five Klees, the Arp, the Picasso, and one of his three works by Fernand Léger.

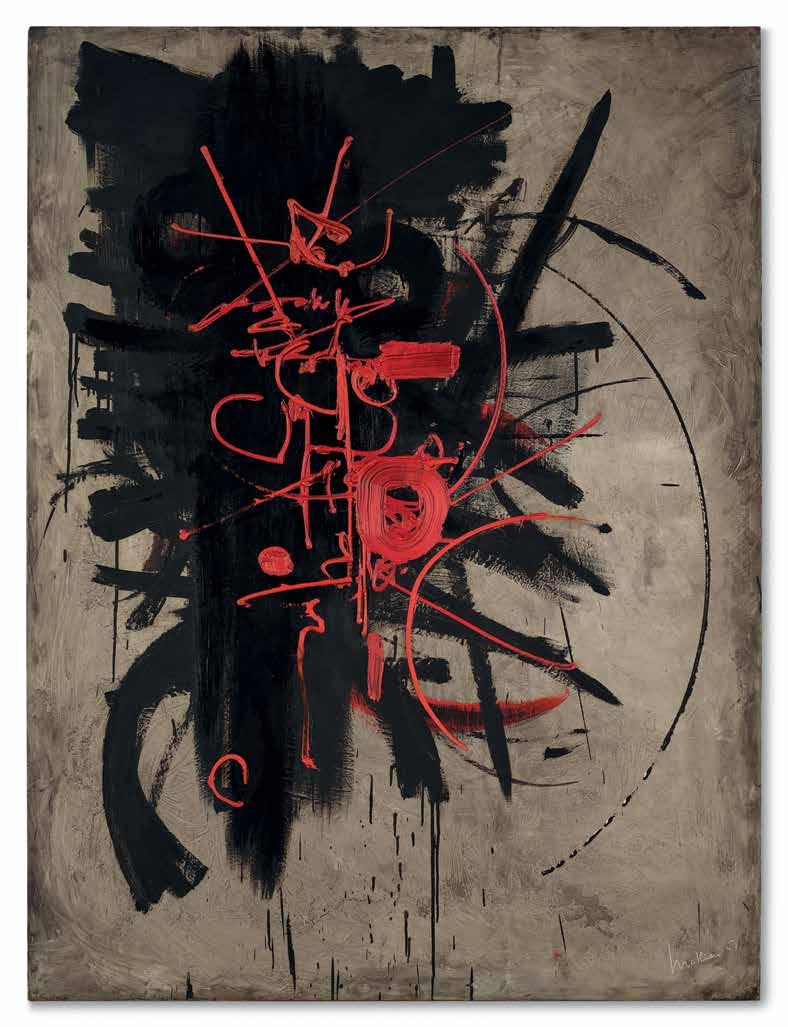

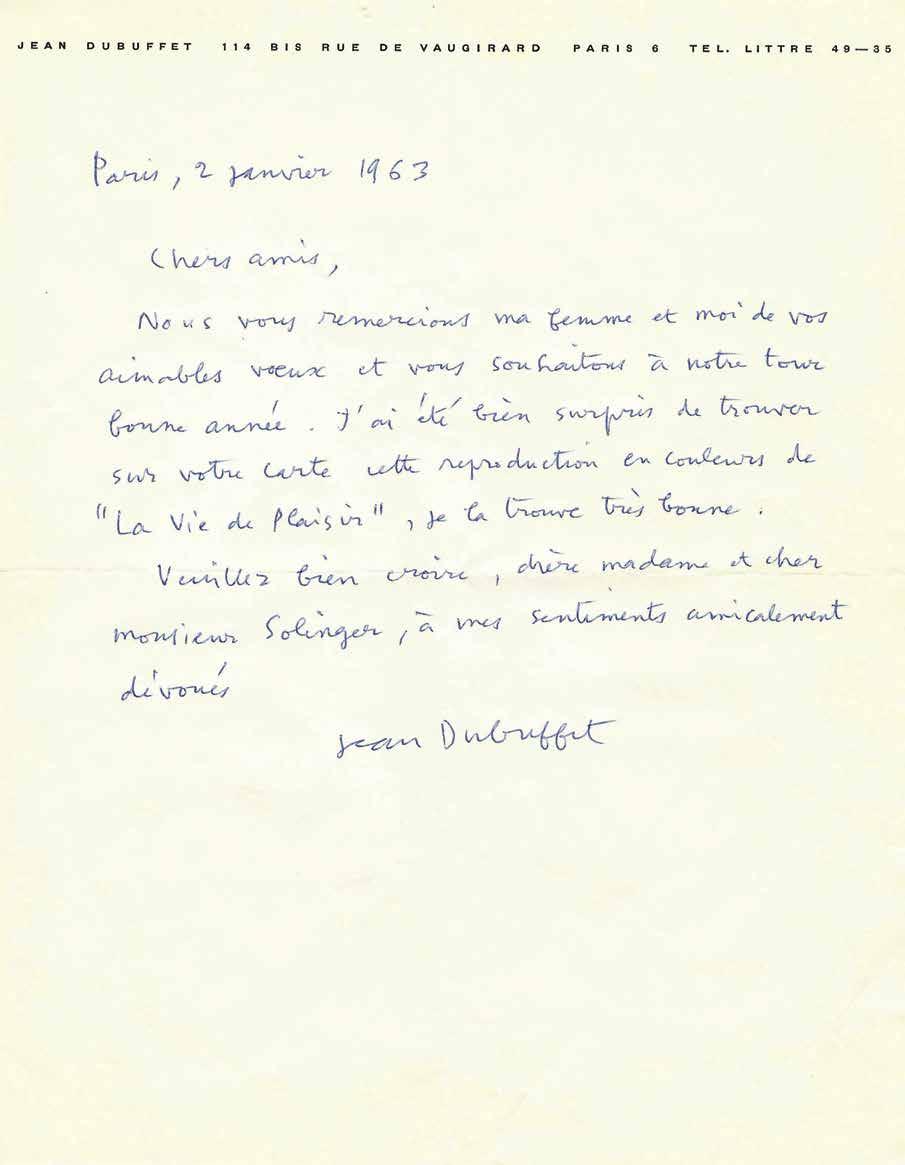

The critic Clement Greenberg, who had described de Kooning’s 1948 exhibition as “magnificent” in the April issue of The Nation wrote a year later of Dubuffet’s self-description as “primitive” in the March 1949 issue of Partisan Review. However, he said that in creating what the artist also called “art brut ” (“raw art”), “Dubuffet borrowed from Klee the key to unlock the spontaneity in himself.” I do not know whether Solinger followed Greenberg’s writings in his admiration of de Kooning, Dubuffet, and Klee, but he was building such associations in defining his own taste

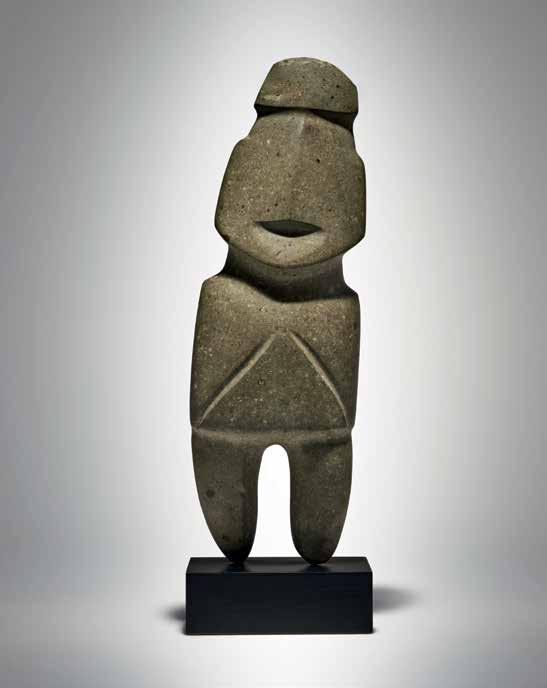

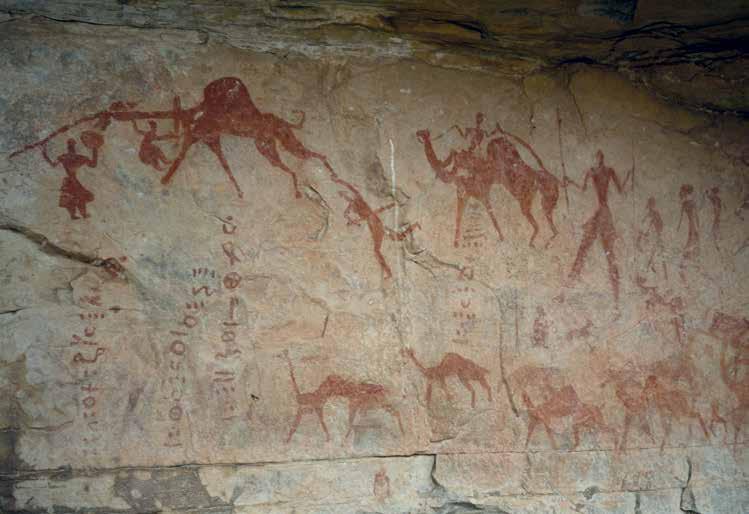

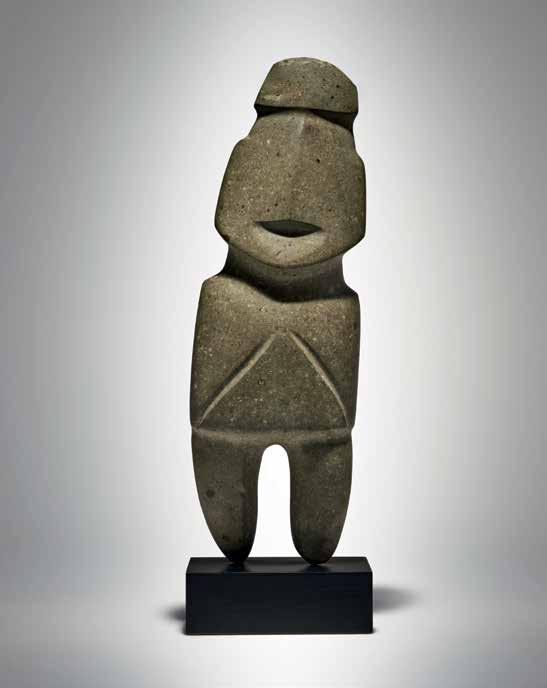

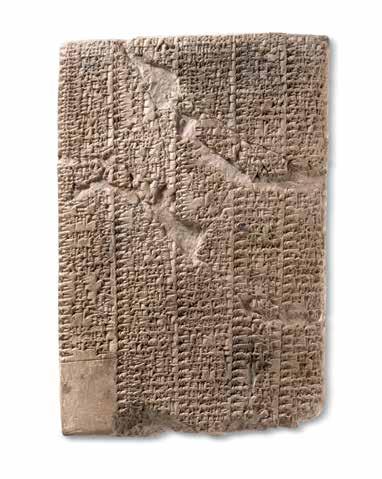

He admired these as predecessors, as he did in a different way the works of art of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, which he began to collect in the mid-1950s. He was not alone in sensing an affinity between the forcefulness of such works and the striking material presence of some contemporary painting and sculpture; and one of his most admired artists, Jean Dubuffet, had famously adopted for his own work the disparaging description of “primitive,” then commonly used for pre-classic sculptures outside the orbit of Western art.

for art which was challenging because it seemed raw and spontaneous. It is likely that he saw the 1950 exhibition at New York’s Sidney Janis Gallery of Young Painters in the U.S. and France, with a de Kooning and a Dubuffet juxtaposed on one of its walls. The dealer Leo Castelli, given his European contacts, had helped Janis to organize the exhibition, but supposedly said that “the show was a bit silly, and purists like Charles Egan, the dealer who handled de Kooning, took a very critical view. It proved one

15 Lot 16,

Paul Klee, Gedenkstein für N. Henri Laurens, Le Repose (Modern Day Auction); Jean Dubuffet, Prompt Messager (Modern Day Auction)

Photo: circa

1960s

Left Cover of the exhibition catalogue, Ancient Art in Middle America, The Stable Gallery, New York, 1956

Right Exhibition announcement for Jean Dubuffet: Recent Paintings, Collages & Drawings, Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, 1954

thing, however, that there really was no connection, except on a very superficial level, between European and American painting.” Clearly, Solinger did not agree.

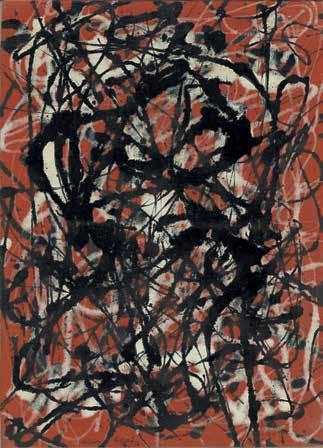

But before further considering his taste, I should mention a major work that he brought home and then parted with: Jackson Pollock’s Lavender Mist, one of the enormous horizontals in the artist’s late1950 exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. As explained in the catalogue of the 2002 exhibition mentioned above, “in the middle of the night he heard a terrible cracking

budget. As Solinger drolly observed in his conversation with Cummings, “Paintings, like strawberries, should be bought when they’re plentiful and cheap.”

He had the perception to buy the right ones when they were. His perception was that the finest mid-century paintings were those in which the marked, tactile surface was prominent. Effectively, his taste re-engaged what had become prominent a century earlier, when the painter Eugène Delacroix complained of the early nineteenth-century Neo-Classical artist

sound. The huge Pollock had pulled the wall down, itself miraculously unharmed. Lavender Mist now hangs on sturdier walls at the National Gallery.”

Connoisseurs of missed opportunities will recall how Henry Pearlman likewise gave up Henri Matisse’s huge Bathers by a River, which went to the Art Institute of Chicago. Still, in both cases, one enormous canvas in a collection of easel paintings would have depreciated the power and the kinship of all the rest. And certainly challenged the

Jacques-Louis David for his “affectation of contempt for the material means.” David’s and his follower’s paintings, he said, “lack this precious quality without which the rest is imperfect and almost useless… the charm [of] the worker’s hand.” David was not a painter “whose execution rises to equality with his idea…. In Davidian painting, the epidermis is everywhere lacking.”

These words, which Delacroix wrote in his journal on several days of January 1857, are in the language of Romanticism, not

of modernism; yet their message was influential upon what had happened later in the nineteenth century, then on what had been growing in importance in the decade prior to 1957. Solinger would have agreed with Delacroix. In 1956, he told a reporter for the Cornell Daily Sun that “subject matter doesn’t matter,” and insisted to Cummings that art was a visual not an intellectual experience. Therefore, neither illusionistic painting, be it realistic or surrealistic, nor refined geometric abstraction, both of which had gained such attention through

de Kooning that so impressed him in 1948 were composed, as Greenberg observed, of thin paint spread smoothly that “identifies the physical picture plane with an emphasis other painters achieve only by clotted pigment.”

And the great 1950 de Kooning collage in the Solinger Collection was composed of multiple pieces of paper with thin paint spread smoothly across them. Those who saw de Kooning at work have described how he would make drawings, scatter them on top of each other; make a drawing from the result; reverse it, tear it in half; recompose it and make a drawing of

the 1930s, were of interest to him. What he admired was the work of a painter “whose execution rises in equality with his idea,” and came to believe that de Kooning was the greatest American artist of the twentieth century, since he, more fully than anyone else, had revived such emphasis on the material means of painting.

As Rosenblum pointed out, “Solinger’s taste was clearly for surfaces that were roughhewn and for emotions that still seem heated and unresolved.” However, the paintings by

that—then move into color, composing with planes, scattering, overlapping, and adjusting them until he was satisfied. His next and usually final step was to move into painting, replacing the paper planes as he did so. The Solinger work is a rare example of the extraordinary result when he did not take that final step: it comprises a sandwich of thin layers of color held together by thumb tacks within which what de Kooning called “slipping glimpses” of images appear and disappear as we look at it, notably the staring eyes in the top-left corner.

16 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 17

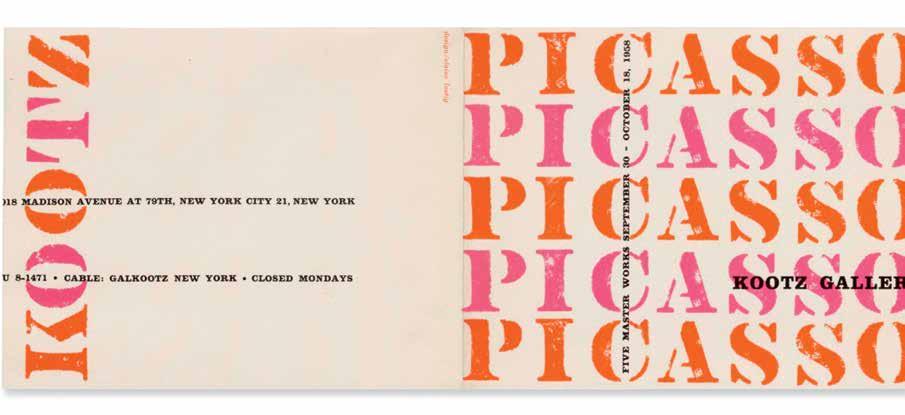

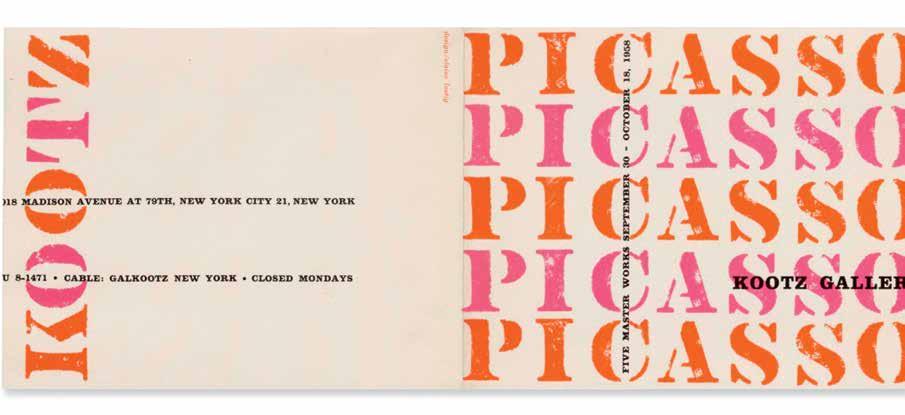

Checklist from the exhibition Picasso: Five Master Works 1958, Kootz Gallery, New York, in which Solinger’s Femme dans un fauteuil was included

“So I commenced to go around to commercial galleries and museums, in a very systematic way, and then ultimately, in 1948, I bought my first painting... That was an act of great courage.”

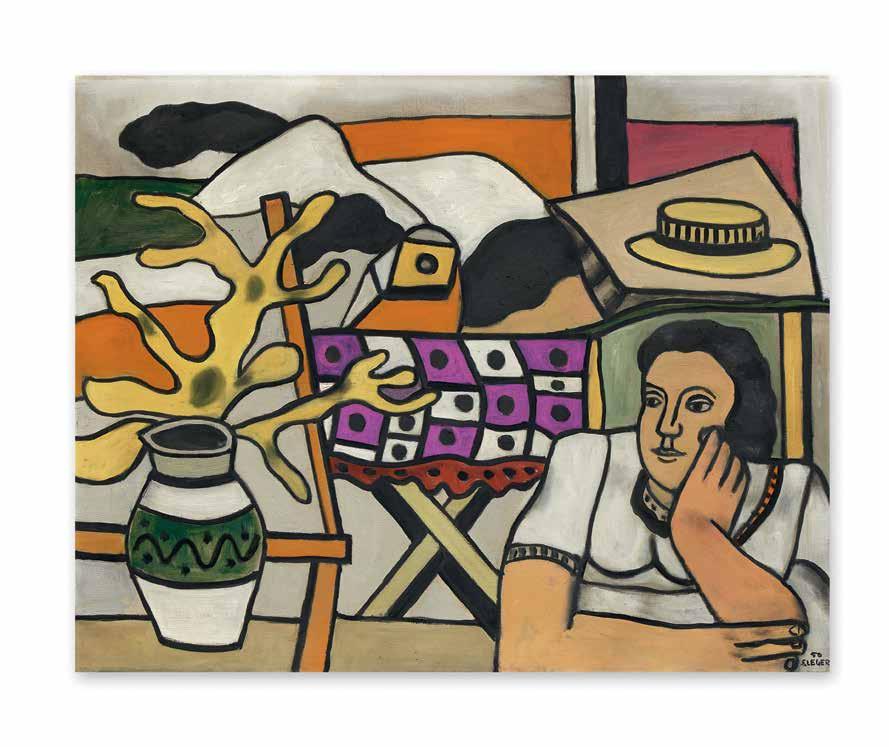

Nonetheless, while Léger fully deserves his place as an admired predecessor in this mid-century collection, his earlier School of Paris status does set his work apart. This is also true of what may justly be called the most extraordinary painting that Solinger bought, Picasso’s 1927 Femme dans un fauteuil. It earns its thematic place in the collection as an image of raw power, yet it speaks louder than anything else. Solinger bought this in 1958 and then loaned it (perhaps that was a condition of the sale?) to the exhibition, Picasso: Five Master Works,

which opened at the Kootz Gallery, New York, at the end of September of that year. We do not know whether he had been offered any of the three works in the exhibition that appear not to have been sold. If so, two were modeled in a vigorously three-dimensional manner, and the third was on the threshold of Surrealism. (The exhibition checklist is reproduced in the present catalogue.)

Solinger’s painting was the earliest, the flattest, and most conspicuously on the threshold of figuration and abstraction; by far the most adventurous.

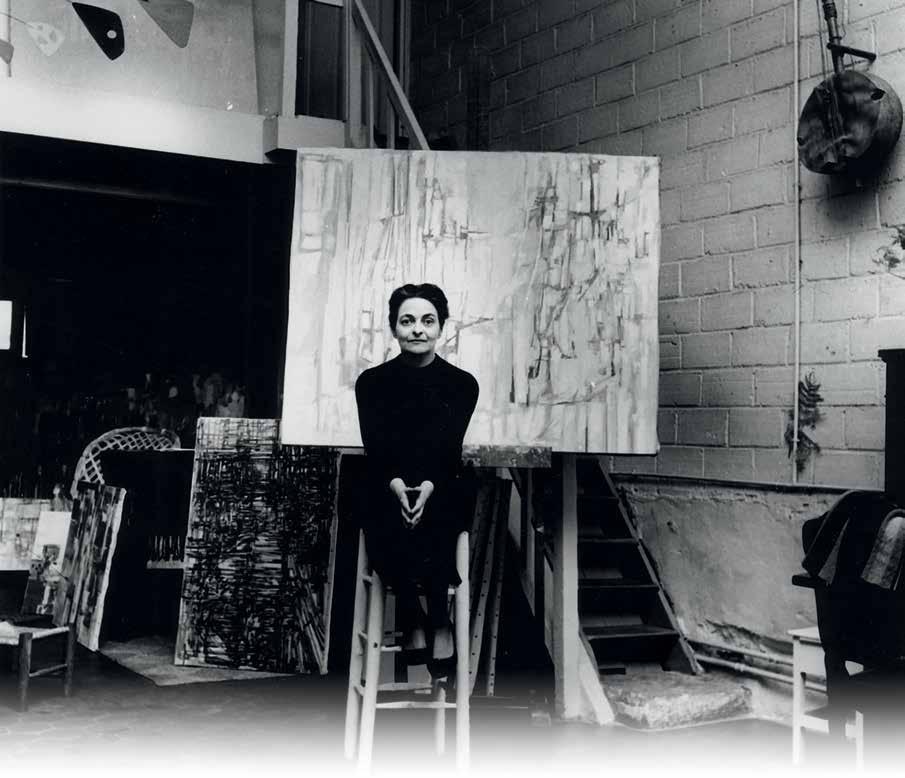

True, many other works in the Solinger Collection reveal clotted pigment—or better, what Delacroix nicely described as an epidermis, a skin of paint, whose tactility is so accentuated as to make it seem rough-hewn. Such works include, most conspicuously, two of the Dubuffets in which sand is mixed into the paint; and, more programmatically, the wall-like Composition of Nicolas de Staël, a work that Solinger apparently bought in fifteen seconds, and which recalls one of Paul Cezanne’s friends, Antony Valabrègue’s description of his early tactile works as “mason’s painting.” Viewers may find allusions to built surfaces in works by other French artists in the collection: to a carpentry screen in Pierre Soulages’s Peinture 92 x 65 cm 7 fevrier 1954, and to a woven, partially transparent cloth in Maria Helena da Silva’s untitled composition, a work with the delicacy of Solinger’s own paintings. And his own interest in making works on paper that glow with an internal light unquestionably influenced—and was influenced by—his enthusiasm for Klee.

18 SOTHEBY’S

DAVID M. SOLINGER: ORAL HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART, 1977, N.P.

Catalogue for the exhibition Alexander Calder at Curt Valentin Gallery, New York, 1955.

Lot

13, Nicolas de Staël, Composition;

Lot

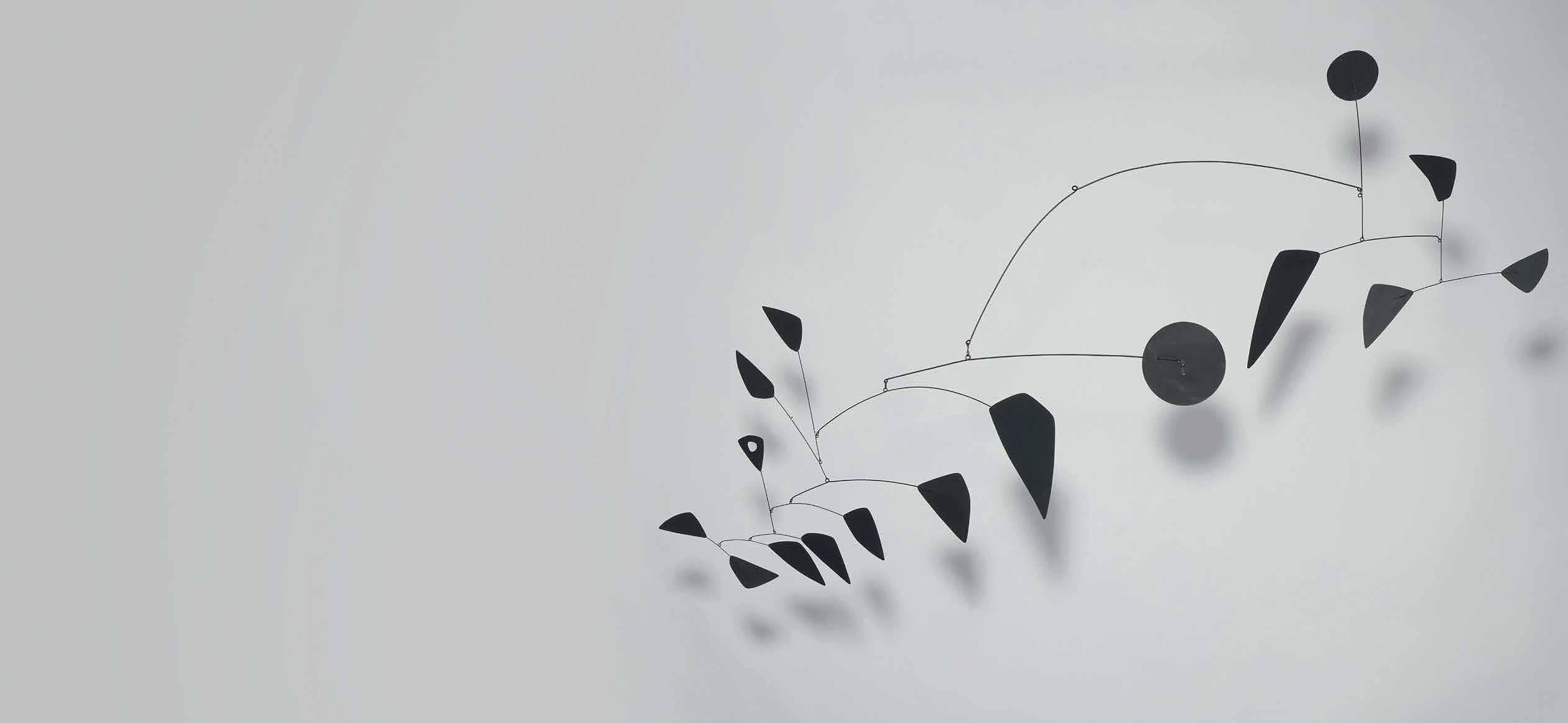

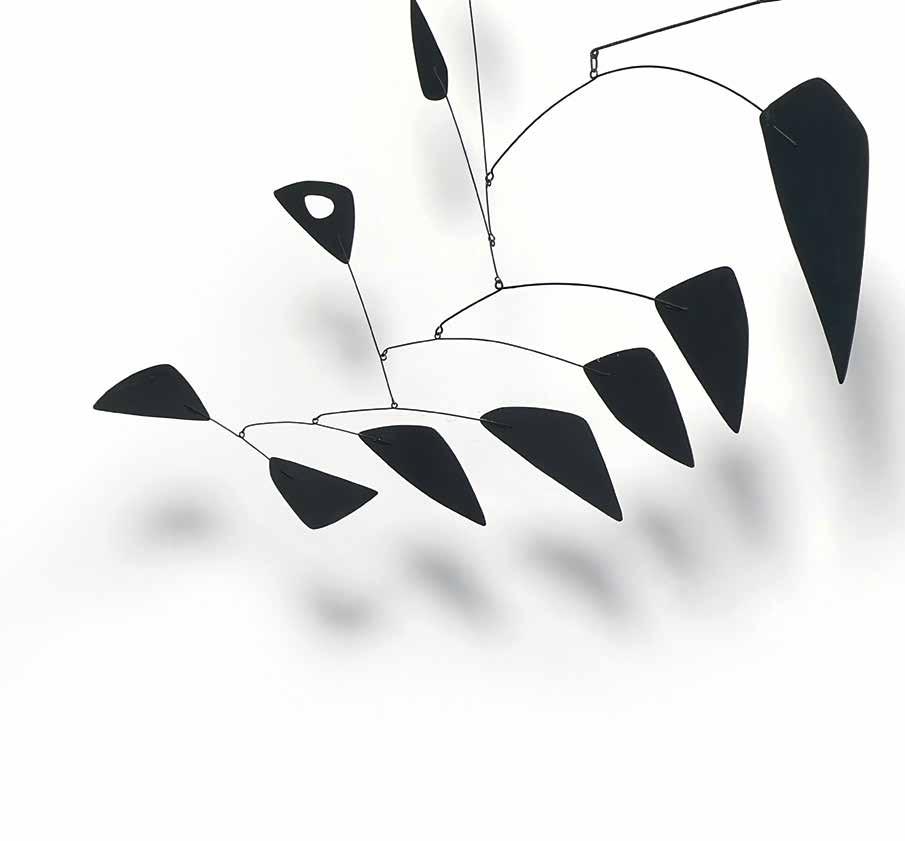

3, Alexander Calder, Sixteen Black with a Loop;

Lot

7, Jean Dubuffet, Chamelier;

Lot

22, Joan Miró, Femmes et oiseau devant le soleil Photo © Visko Hatfield

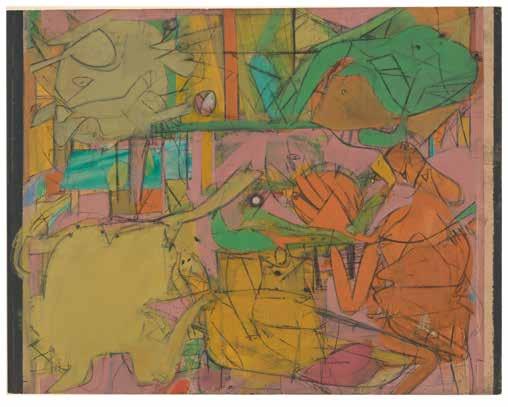

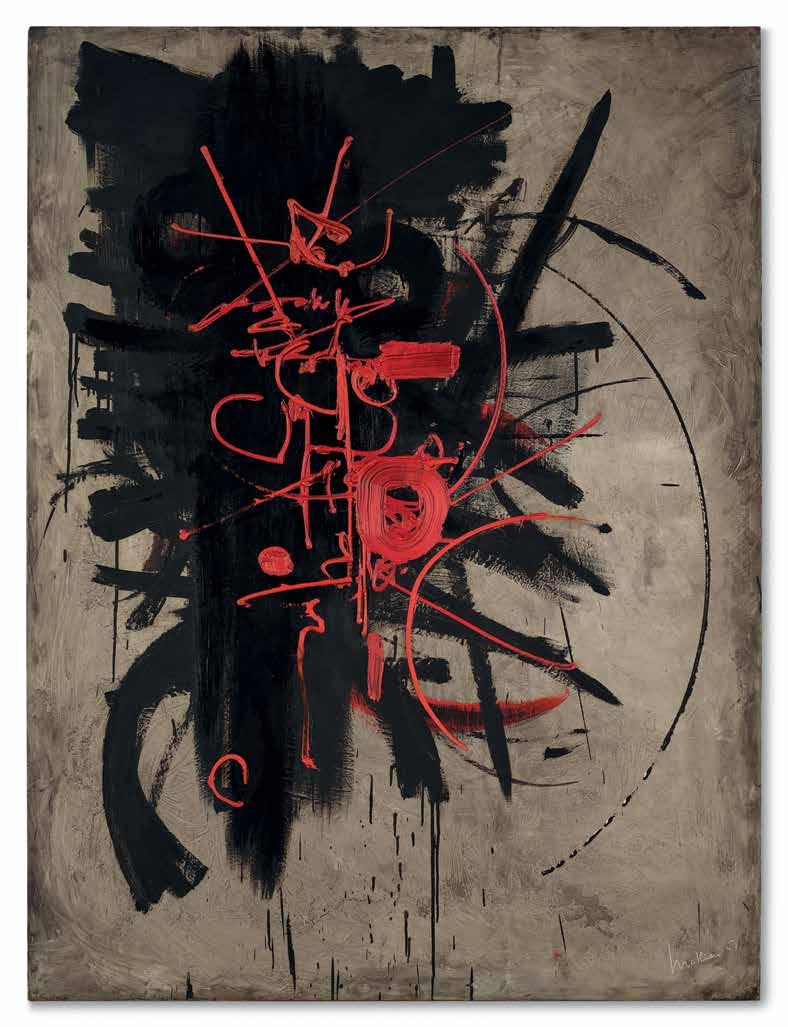

The gracefulness of his Klees seemed to be a necessary corollary to the rawness of his Dubuffets; yet Klee also spoke to Solinger’s interest in the seemingly unschooled quality that Dubuffet had learned from Klee. And he could find imagery in Klee’s amazing inventiveness that associated it with works as different as those by Arp, Baziotes, and Miró. Moreover, Solinger’s adeptness in recognizing likenesses in unlike artists extended to seeing Arp’s famous characterization of his sculptures as “concretions”—signifying the natural process of coagulation and thickening in the natural world— as associating a work as elegant as his Fruit méchant with the densest of the Dubuffets in the collection. It was not difficult to see that a Dubuffet and a Giacometti had a lot in common; nor that a Calder was akin to a Miró. However, it took imagination to see that Mathieu’s Camp de Carthage would, for all its vehemence, be a good fit with Miró’s Femme, étoiles; and that Fernand Léger’s description, recorded in the 2020 catalogue, of a “personification of the enlarged detail” and “individualization of the fragment” in his packed compositions belonged to a modernism that included the 1950 collage by de Kooning.

VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 21

David M. Solinger at Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1981

David M. Solinger at Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1981

“To me, art is a pleasurable experience. I look at pictures. I like pictures that seduce the eye. That is not to say that I don’t also like pictures that are like a blow between the eyes, that are very strong, and are very powerful, that are very moving. I think pictures should be accepted on a visual basis.”

The Solinger family graciously agreed to loan me this work for the exhibition, Matisse-Picasso that I curated with colleagues in London, New York, and Paris in 2002-03. (They would similarly loan the de Kooning collage to my de Kooning. A Retrospective at MoMA in 2011, believing that Solinger would have wanted to share his most important works when they had not been seen publicly for decades.) In the catalogue for Matisse-Picasso, my colleague Elizabeth Cowling, comparing Picasso’s canvas to Matisse’s contemporaneous paintings of odalisques, described it as “an act of pure travesty; a monstrous female of indeterminate, primal species in place of the iconic beautiful female nude… [one whose] dream may be a nightmare and she is screaming in terror.” When faced by so astonishingly aggressive a work in a private collection, which was rare, William S. Rubin, who led MoMA’s Department of Painting and Sculpture when I first joined the museum, would say to the collector, “It took courage to buy a work like this to live with.” It did; and, I venture to say, it will.

Lot 3, Alexander Calder, Sixteen Black with a Loop; Lot 22, Joan Miró, Femmes et oiseau devant le soleil; Lot 10, Willem de Kooning, Collage Photo © Visko Hatfield

DAVID M. SOLINGER: ORAL HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN ARCHIVES OF AMERICAN ART, 1977, N.P.

23

Lot 2, William

Baziotes, Figures

in Net (detail)

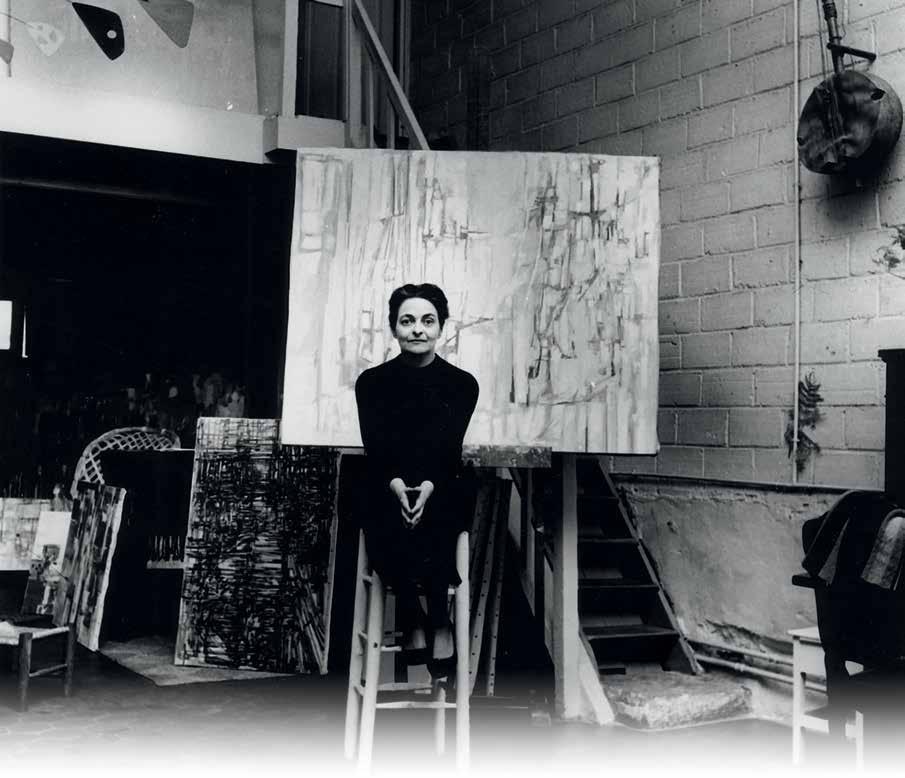

DAVID M. SOLINGER A VISION FOR A NEW GENERATION

“At the brief ceremony opening the Downtown Whitney Museum, the new financial district branch of the Whitney Museum of American Art, David M. Solinger escorted Mayor Lindsay around the elegant modern gallery overlooking the new Uris building at 55 Water Street, while commenting on each artist’s place in American art. They passed before Raphael Soyer’s Office Girls then strolled over to gaze at de Kooning’s Door to the River. The mayor, paying much more than a ritual visit, appeared fascinated and amused by Solinger’s insights. Solinger has been the Whitney’s president since 1966 and was in the first group of non-Whitney trustees appointed to the board in 1961. A founder and president in 1957 of the supporting Friends of the Whitney… Solinger was in a happy mood at the new branch opening. “

‘The significance of this event is that a number of museums have talked about opening branches but the Whitney has done it!’ Mr. Solinger noted that the gallery will serve some 100,000 residents of the area and 500,000 or so workers, ‘who come in every day and depart again.”

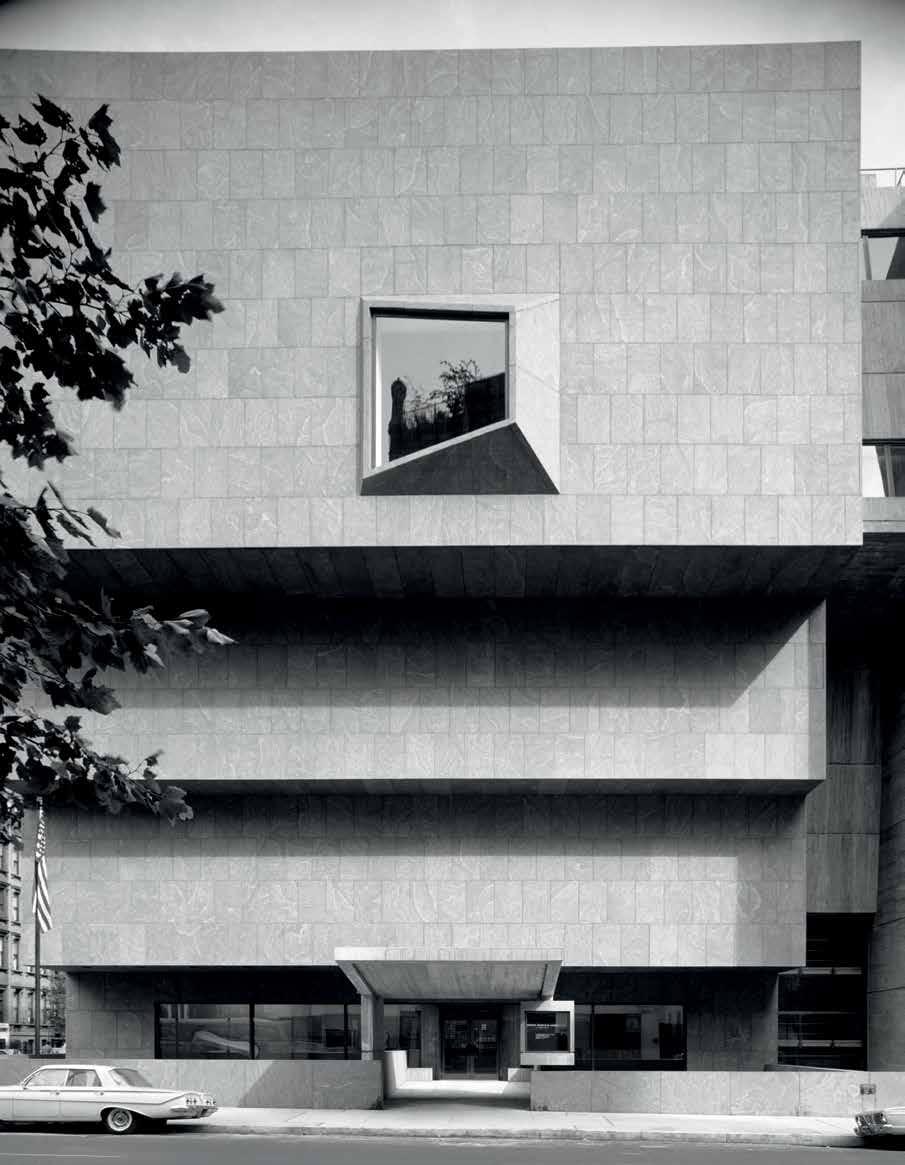

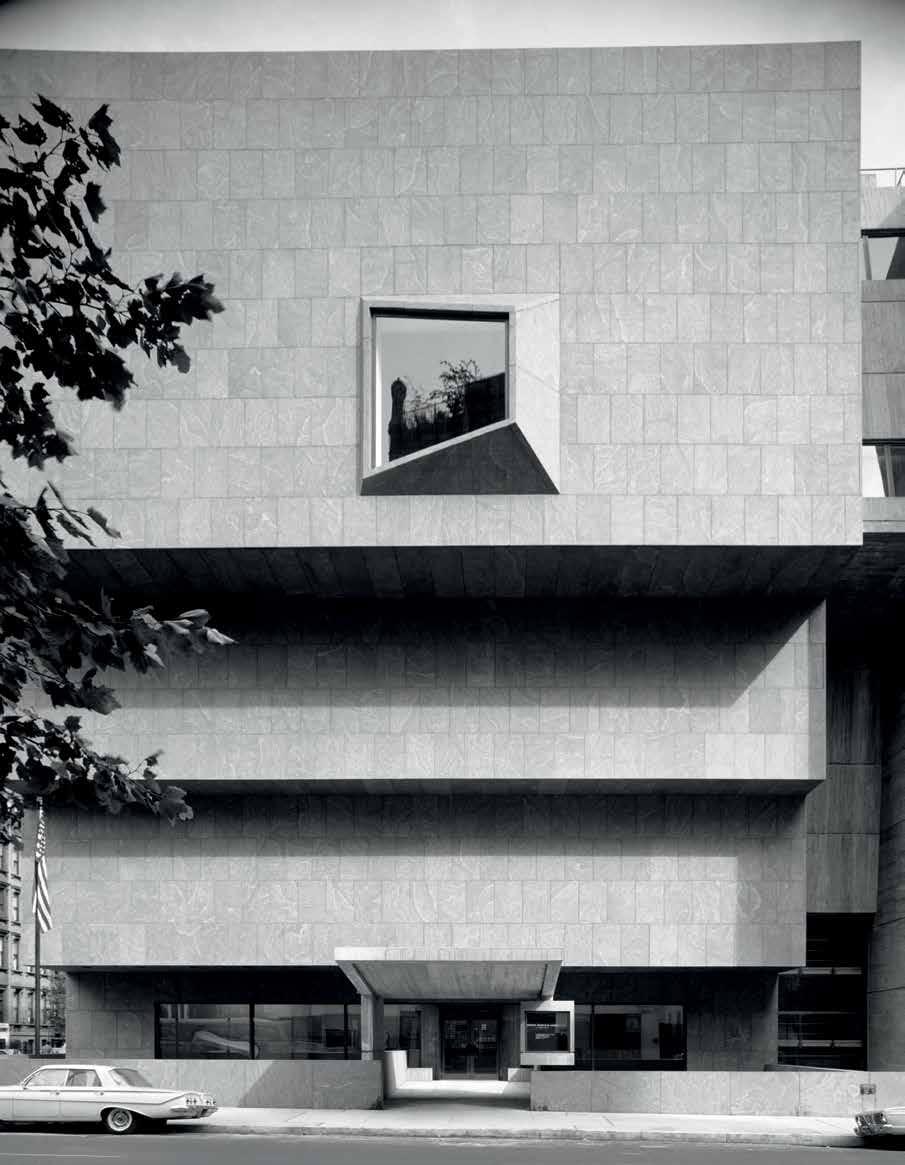

The Whitney Museum of American Art at the Breuer building in New York, 1960s. Photo © Ezra Stoller / Esto

The Whitney Museum of American Art at the Breuer building in New York, 1960s. Photo © Ezra Stoller / Esto

27

SALLY HAMMOND, “DAILY CLOSEUP,” THE NEW YORK POST, 20 SEPTEMBER 1973

Above Portrait of David M. Solinger, 1959

Opposite Check from TIME Magazine to David M. Solinger paid for his legal expertise in 1948

David M. Solinger (far right), pictured at a Frank Sinatra concert circa late 1940s

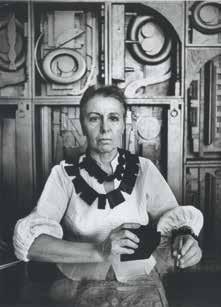

The trajectory of David M. Solinger’s life and work is emblematic of a generation to emerge after World War II that recognized the importance of the arts and cultural institutions as critical to the civic and social health, and future, of a community, whether a city, suburb or small town. David M. Solinger’s passion for the arts led to leadership roles and the realization of new and innovative approaches to museums and institutions across America, marking early transitions toward agency and access. Solinger’s boundless energy, his quiet but resolute diplomacy and his extraordinary prescience were the personal and professional qualities that led to his transformational roles in a multitude of organizations. His legacy resists categorization: reaching beyond his career in law, where he was among the first to specialize in advertising and media law and as legal representative to a number of leading artists; to his transformational work as President of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the first person from outside the Whitney family to hold this position; to his own exploration of art, where his personal confrontation with the challenges of painting brought him closer to the art and artists of his day; to his life-long generosity as a philanthropist, donating significant works to Cornell University (his alma mater), the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Smith College and others; and to today, where his singular eye for extraordinary pictures, his generosity, leadership and enduring vision – as collector, philanthropist and advocate – will continue to influence generations to come.

Born on February 17, 1906, at 95th Street and Broadway, David Solinger was the son of second-generation immigrants from Germany. His father, Morris D. Solinger, held a senior position in a wholesale meat business – an industry that did not appeal to David, who was keen to pursue a career that allowed for autonomy. His inherent drive and intellect led him to pursue higher education, first at Cornell University, and then Columbia Law School. For Solinger, law was a guiding force within his life and those around him, and one which shapes and protects the standards, values, and ethos of a rapidly evolving world.

His law practice was interrupted by the Second World War, however, and in 1942 Solinger was called to serve on the Eastern Defense Command. His innate skill as a communicator meant he was quickly enlisted to the public relations arm of the division, in which capacity he strategized a system for the dissemination of news in the event of an Atlantic Seaboard attack, with the sole aim of “informing the public accurately, and keeping them calm” (David M. Solinger: Oral History, 1989, 1-34).

“Law is precise, it doesn’t give the imagination much sway. That’s where painting comes in.”

DAVID M. SOLINGER

28 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 29

Article

about the new Whitney building at the Breuer building, Art Voices Magazine

Spring 1953

Upon his return to New York in 1945, Solinger resumed his law practice with Solinger & Gordon, the firm he co-founded. As a lawyer, his work not only included representation of key retail titans, such as Gimbel-Saks (later Saks Fifth Avenue) — but also pioneering partnerships in the developing fields of radio and television, advertising, and art law. “Lawyers without a specialty were beginning to be rarer and rarer. So I combined that perception with the fact that communications were developing, that television, particularly, as a new medium was developing. I decided that I would do whatever was necessary to be thought of as someone who was an expert in this field” (Ibid., 2-65). His foresight would make him one of the first lawyers to develop a specialty in the industry, preceding the vast majority of his peers.

Solinger’s advocacy for and interest in art was born from a chance encounter, shortly after his return from duty, when a friend enrolled for Monday night art classes at YMHA at 92nd Street and encouraged Solinger to join him. Despite his busy and rapidly developing career in law, Solinger made a practice of carving out time to paint. He describes: “I became not a Sunday painter, but a summer painter. I would take my vacation by going off to paint, much to the amusement of some professional artists who couldn’t understand how it could be a vacation for me to spend six or eight or ten hours a day painting” (Ibid., 2-71). Cathartic and freeing, art offered Solinger a key counterweight to the demands of a practice in law. “Law is precise, it doesn’t give the imagination much sway,” he once said, “That’s where painting comes in.”

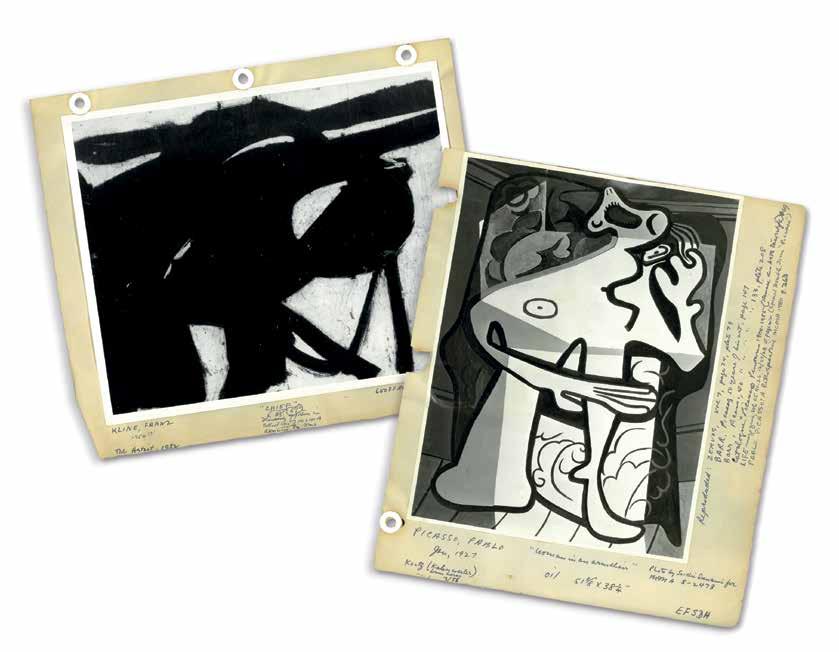

David Solinger's personal cataloguing records (from left to right): Franz Kline, Study for Chief Pablo Picasso, Femme dans un fauteuil; Alberto Giacometti, Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau)

David Solinger's personal cataloguing records (from left to right): Franz Kline, Study for Chief Pablo Picasso, Femme dans un fauteuil; Alberto Giacometti, Trois hommes qui marchent (grand plateau)

32 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 33

As Solinger’s love of painting grew, so too did his desire to understand how other painters addressed the same challenges he encountered. Beginning to visit galleries and museums, he quickly moved from admiring works upon gallery walls to a desire to live with art every day. After his first acquisition in 1949 of a painting by Hawaiian-born Reuben Tam – now in the collection of the Whitney Museum— from the legendary Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, Solinger was, in his own words, unstoppable: “It took a lot of courage for me to do that, because it meant that I was backing my own judgment in a sense. I was buying something that was unique. I was spending money that I had earned. And like a virus that gets into the blood stream, which can’t be cured with antibiotics but just has to run its course--it never did run its course, because I started seeing and buying other works of art” (Ibid., 1-45).

Collecting largely from the 1950s to the early 70s, Solinger found himself at the center of the art world in New York – a moment when New York itself was fast becoming the epicenter of literature, music, commerce, and the visual art world at large. From his frequent visits to museums and galleries, Solinger quickly forged lasting relationships with many of the most influential dealers and gallerists in the city – including Pierre Matisse, Samuel Kootz, Sidney Janis and Charles Egan – as well as with many of his favorite artists. He dined with Willem de Kooning and Jean Dubuffet, took painting classes from Hans Hofmann, spent summers in Provincetown with Hofmann and Franz Kline, and acted as legal representative for many others – John Marin, Louise Nevelson, and Robert Motherwell among them. Solinger was also very much engaged in the reemerging art climate in Paris, through his friendships with several gallerists, including Aimé Maeght, Michel Warren, Louis Carré, and the curator and critic Michel Tapié. As an early visitor from America to Alberto Giacometti’s Paris studio in 1950, Solinger was transfixed and obsessed with the artist and his work. Subsequently he acquired several works from Galerie Maeght beginning in 1951, and in 1962 gave Monumental Head, 1960, to the Museum of Modern Art.

Left Telegram from David M. Solinger to Willem de Kooning scheduling a studio visit, 1952

Right

Letter from Thomas B. Hess to David M. Solinger regarding the loan of Willem de Kooning's Yellow River, 1968

Cover of The Museum of Modern Art: Painting and Sculpture Collection 1950

34 SOTHEBY’S

VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 35

“A little over a year ago, a group of quick-thinking patrons banded together to see how the Whitney’s problem could be solved. They swiftly organized a non-profit membership organization called Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art, ‘devoted to furthering the welfare and progress of contemporary art’ … David M. Solinger, lawyer and prominent collector (a long standing good amateur painter) was appointed president. He phrased the by-laws, quickened the detail work, and in no time, the Friends were operating full scale. Their aim was, and still is, to augment the Whitney’s meager allotment for the purchase of contemporary art.”

One of these new friends, Alfred Barr, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, encouraged Solinger’s appreciation for museums and public institutions. Having attended Franz Kline’s inaugural solo exhibition together, Barr suggested that Solinger acquire one of Kline’s paintings and donate it to the Museum. Solinger promptly agreed; Kline’s Chief is now in MoMA’s permanent collection and has become one of the artist’s best-known masterworks.

In 1956, another friend, Lloyd Goodrich, reached out with an invitation to join a meeting with others who were interested in the Whitney Museum. As a result of this meeting, Solinger organized the non-profit corporation “The Friends of the Whitney Museum;” an entirely novel idea for the time, and one which proved to be an extraordinary success.

Within a decade, Solinger had risen to become President of the Whitney Museum – the first non-family member to hold this position. In this role, he steered the Whitney from a small private institution to the internationally acclaimed museum it is today, including planning and fundraising for the construction of the Marcel Breuer building at 75th Street and Madison Avenue. The now-iconic building established the Whitney as a taste-making force in the contemporary art scene, and under Solinger’s tutelage the museum built the reputation for driving innovation and challenging boundaries that continues to define it today.

In the course of all this, Solinger initiated the purchase of some of the museum’s greatest works. He recalls negotiating the acquisition of one masterpiece: “I called Bill de Kooning, whom I know…. [and] I met Donald Blinken at [his] studio. And as I entered…. I saw on the easel a picture that I immediately fell in love with and knew that this was the picture that the Museum had to have. [We had lunch at Luchow's and] in the course of the conversation, he told us he was very much interested in building a patrimony for his daughter, Lisa, then two or three years old. It was winter time, but the 1st of January had not yet arrived, and I suggested to him that he might consider giving the picture to Lisa in fractions over a three year period [and that] we would then buy her fractional interests [over a number of years]. That may have persuaded him to sell us the picture” (Ibid., 1-51-52). That work was de Kooning’s Door to the River

Further to his pioneering work as President of the Whitney Museum, Solinger’s generosity –as patron, leader, and visionary benefactor – was expansive. As a long-serving board member of the American Federation of Arts, he supported institutions, artists, and collectors in organizing travelling exhibitions, with the goal of making art more accessible to all. Always devoted to his alma mater, Solinger invested significant time and energy in developing Cornell University’s collection, serving as founding Chair of the Johnson Museum’s Advisory Council, and generously loaning and donating to the collection there. David Solinger’s legacy of insight, character, generosity and humanity has assuredly shaped new generations of institutional leadership, continuing his mission to ensure museums are strong and stable institutions, accessible, inclusive, and reflect the art of their time.

Left to right Lloyd Goodrich, Director of the Whitney Museum; Mrs. Michael Irving; Marcel Breuer, architect' and Mrs. Flora Whitney Miller, President of the Board of Trustees.

Photo: Art Voices Magazine, Spring 1965

Flora Whitney Miller cuts the ribbon during the dedication ceremony for the museum's new building, 27 September 1966. Also pictured: the building's architect, Marcel Breuer; Mrs. John F. Kennedy; Lloyd Goodrich, director of the museum, and architect Hamilton Smith. Photo: Bettmann / Getty Images.

36 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 37

DORE ASHTON, “BIG YEAR FOR WHITNEY MUSEUM FRIENDS,” THE NEW YORK TIMES, 5 JANUARY 1958, SECTION X, P. 15

“Mr. Solinger thinks of being president of the museum ‘as a job of being president of any institution. It’s a job of leadership. It’s incumbent upon a president to have imagination, to guide the destiny of an institution and, working with the trustees, to meet any challenges of the future’.”

"PRESIDENT OF WHITNEY: DAVID MORRIS SOLINGER,” THE NEW YORK TIMES, 2 DECEMBER 1966, P. 34

VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 39

David M. Solinger in the entry corridor of his apartment, New York, featuring a selection of works from The Collection

David M. Solinger in the entry corridor of his apartment, New York, featuring a selection of works from The Collection

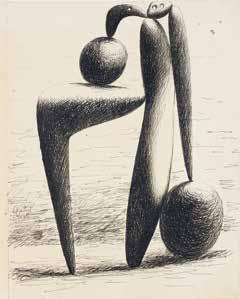

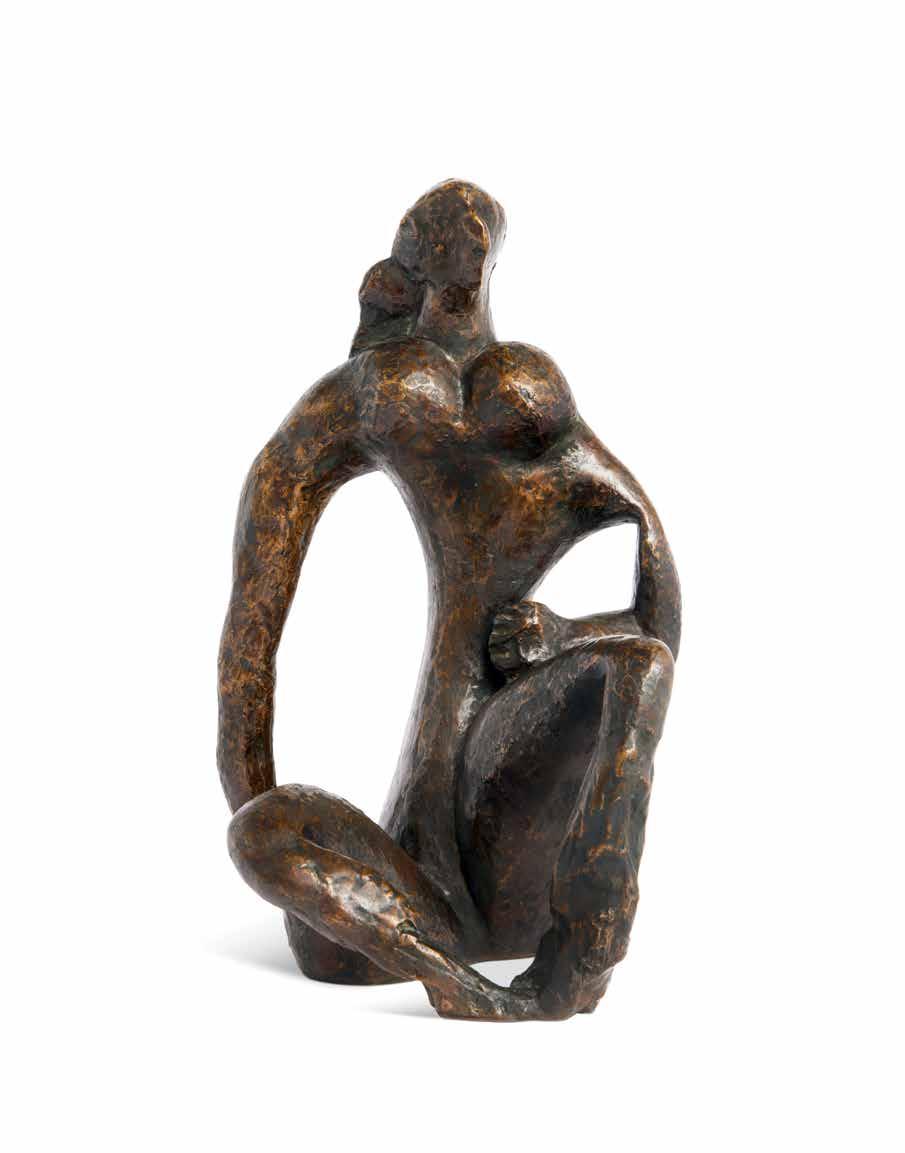

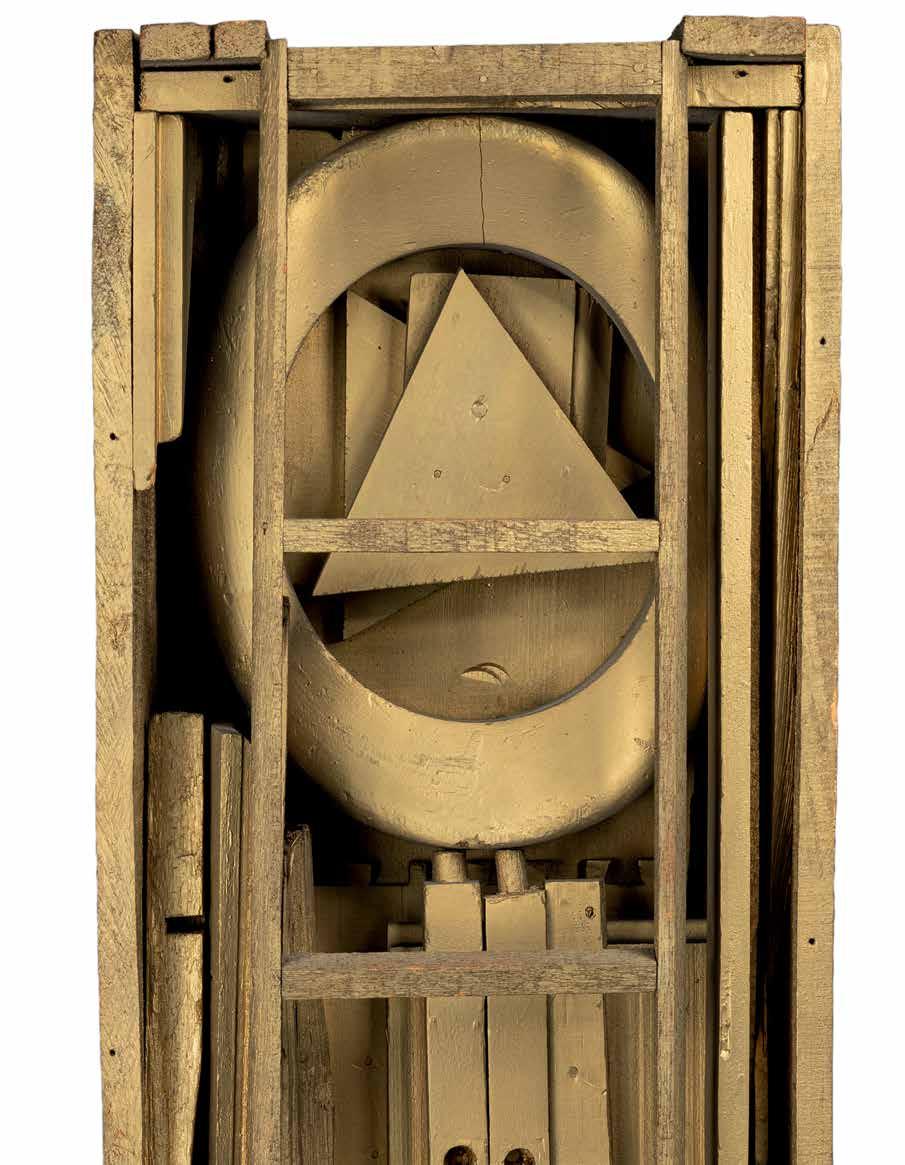

PROVENANCE David Thompson, Pittsburgh (until at least 1960) Martha Jackson Gallery, New York Acquired from the above in 1963 by the present owner EXHIBITED New York, Buchholz Gallery, Jean Arp, 1949, no. 4 (titled Bad Fruit) Zurich, Kunsthaus, Thompson Collection: Aus einer amerikanischen Privatsammlung, 1960, no. 282 (titled Böse Frucht) Ithaca, Cornell University, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, The David M. Solinger Collection: Masterworks of Twentieth-Century Art, 2002-03, p. 17, illustrated in color (titled Naughty Fruit and listed as French marble) 1 JEAN ARP 1886 - 1966 Fruit méchant pink limestone height: 19 ¼ in. 49 cm. Executed in 1936; this work is unique. $ 500,000-700,000 LITERATURE Carola Giedion-Welcker, Jean Arp, New York, 1967, no. 27, p. 109 (titled Angry Fruit) Ionel Jianu, Jean Arp, Paris, 1973, no. 27, p. 67 Exh. Cat., Stuttgart, Württembergischer Kunstverein and traveling, Arp 1886-1966, 1986-88, no. 154, p. 160, illustrated Margherita Andreotti, The Early Sculpture of Jean Arp Ann Arbor, 1989, pp. 284-85, no. 59, fig. 113, n.p., illustrated (titled Naughty Fruit) Kai Fischer and Arie Hertog, eds., Hans Arp: Sculptures—A Critical Survey, Ostfildern, 2012, no. 27, p. 75, illustrated 42 SOTHEBY’S

“Art is a fruit that grows in man, like a fruit on a plant, or a child in its mother’s womb. But whereas the fruit of the plant, the fruit of the animal, the fruit in the mother’s womb, assume autonomous and natural forms, art, the spiritual fruit of man, usually shows an absurd resemblance to the aspect of something else.”

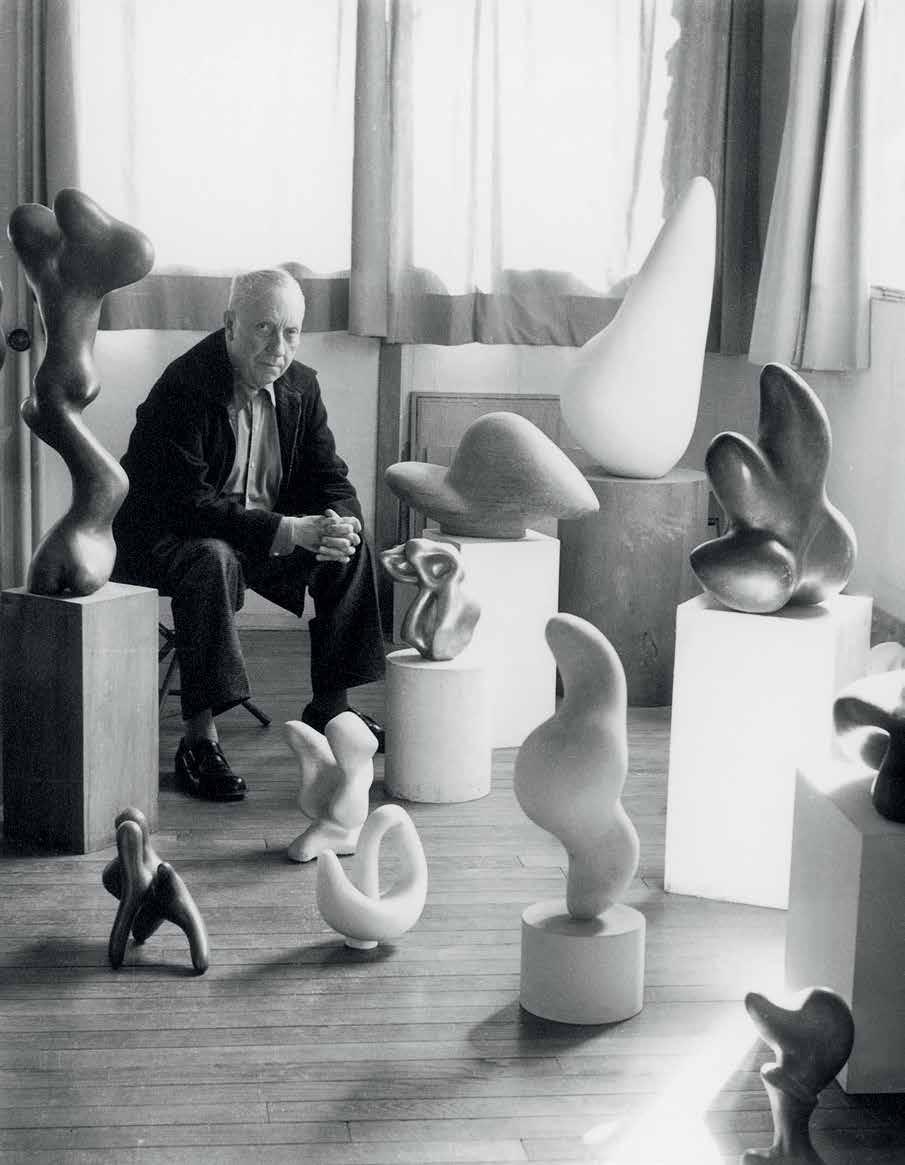

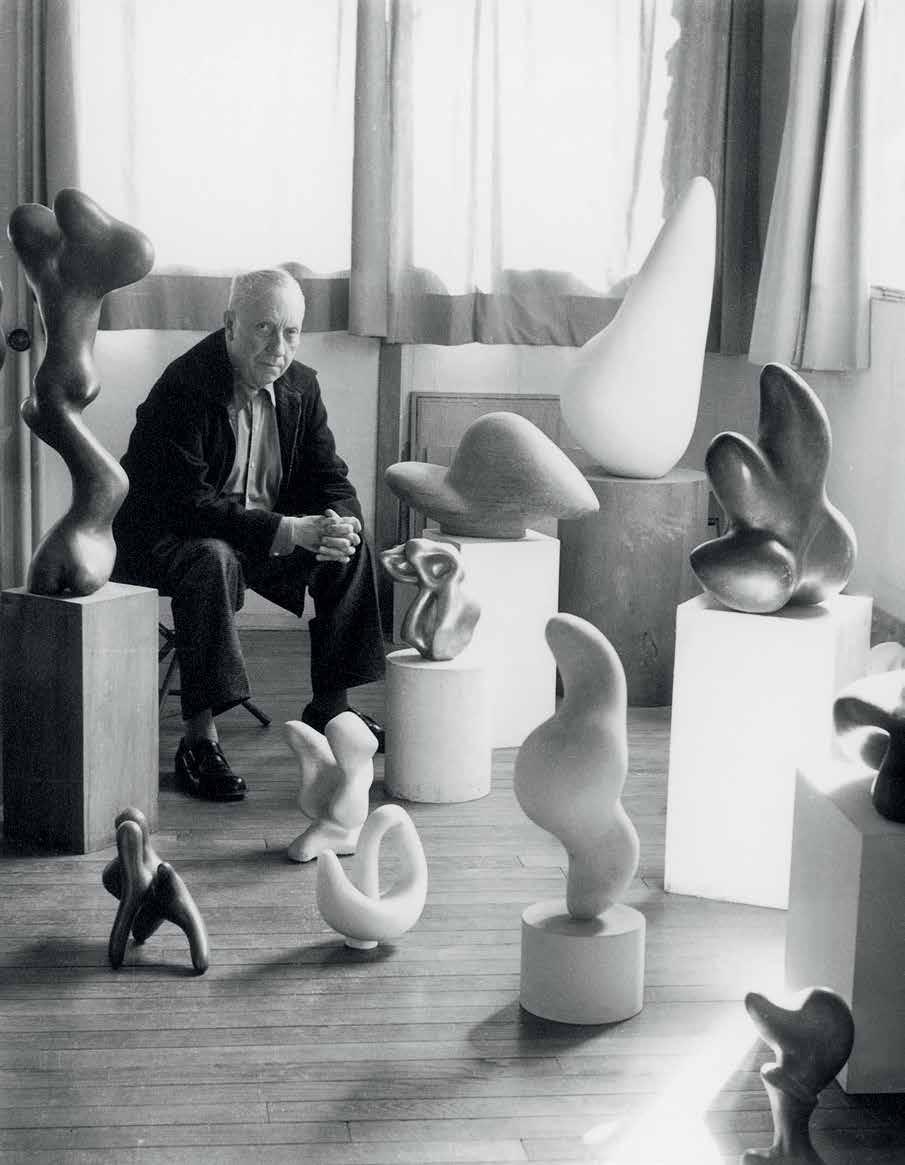

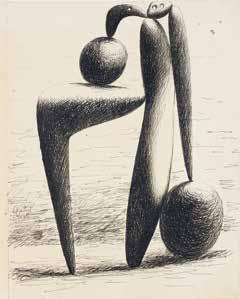

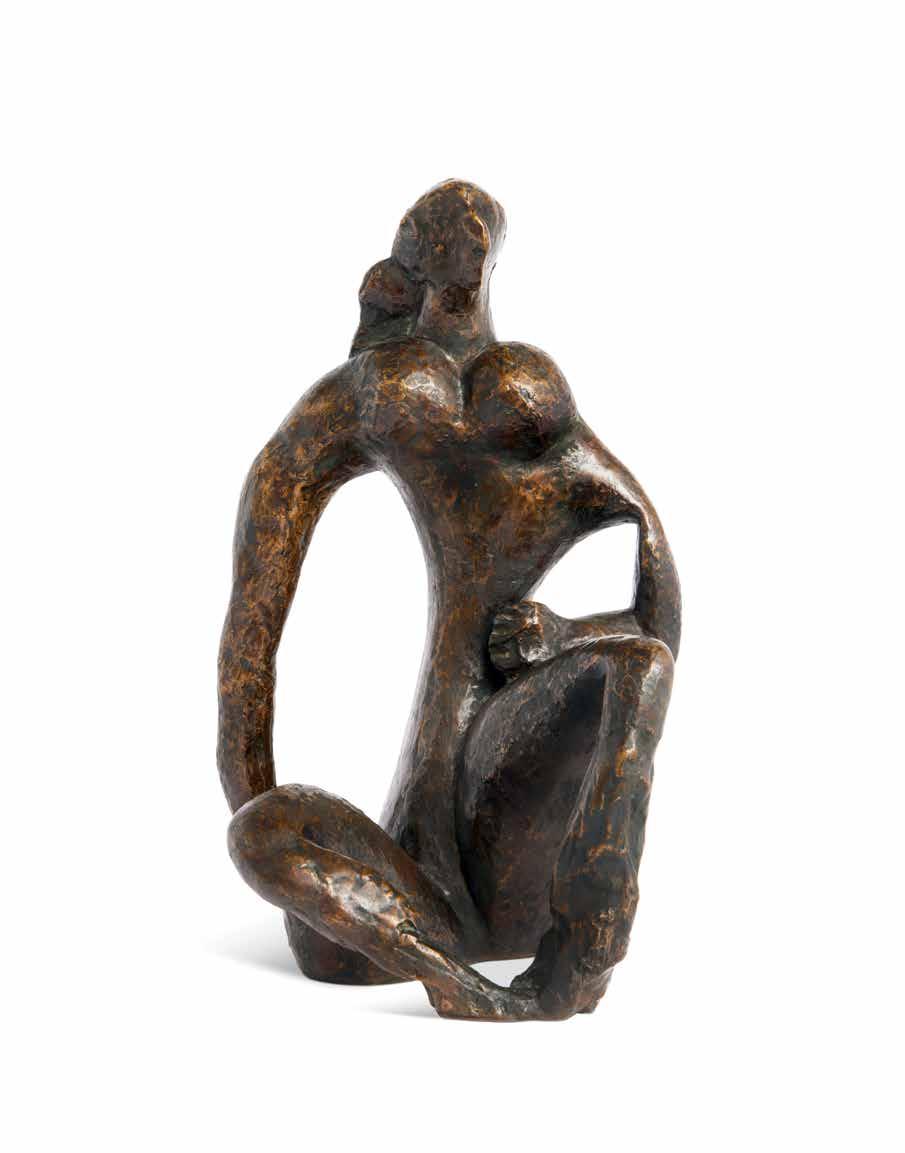

Simultaneously primordial and innately modern, shockingly new and hauntingly familiar, the joyously carved Fruit méchant encapsulates Jean Arp’s distinct ability to capture a sense of life in an object reduced to its essential form. At the heart of Arp’s success is the organic beauty of his sculptures, which seem to manifest from a vision unencumbered by any formal constraints. An important example of Arp’s early foray into sculpture, Fruit méchant is emblematic of the tenets which defined the body of sculptural work he went on to produce over the rest of his career.

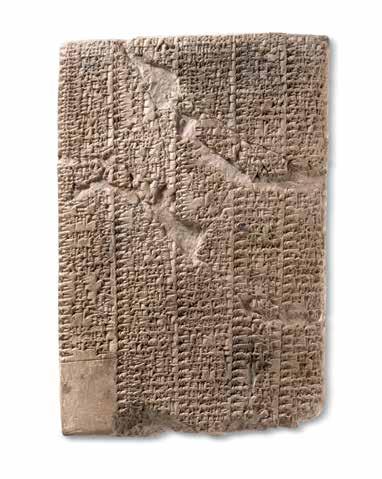

Arp, like many of his fellow Dadaists, emerged from World War I with a raw sensitivity to the destructive capability of modern technology, disenchanted by the dictums of common sense which led society into a conflict of such senseless magnitude. The purpose of Dada, as Arp saw it, was “to destroy the swindle of reason perpetrated on man in order to restore him to his humble place in nature” (Jean Arp, “Notes from a Diary,” Transition, The Hague, no. 21, March 1932, p. 191). Arp’s early Dada reliefs sought to awaken the viewer to the tensions between man and his place in the world, but in the 1930s, as he transitioned to working with sculpture in the round, he instead became transfixed with the unity of man and nature. He found in sculpture the potential to collapse the distance between human and natural form, developing the distinct anthropomorphic language seen in Fruit méchant to describe what exists in between.

Both in title and in form, Arp personifies the Fruit méchant, imbuing it with human emotion and drawing a parallel between its shape and the human hand. The association defies conventional logic, but as such, the viewer comes to see their own experience as being like that of a fruit, and in turn, to see their relationship to the natural world through a new lens. The present work encapsulates the notion of the “surrealist object”—Andre Breton’s idea that the process of seeing an object anew, in a context diametrically opposed to its origins—awakens something in the unconscious that derives an entirely new understanding of the object’s meaning. There is a tension between the fluidity of form and rigidity of material that reflects Arp’s remarkable ability to create something at once tangible and entirely ephemeral. He imbues the banal with a mysticism, and in so doing gives physical shape to abstract emotions.

As Carola Giedion-Welckler writes: “The works of Jean Arp are strange artistic growths, which spring from an ancient and richly stratified cultural soil” (Carola Gidieon-Weleckler, Jean Arp New York, 1957, p. v). There is something inherently and recognizably natural about Fruit méchant—some quality that defies the notion that it was made by hand. The collapsing of this distance between the man and natural-made was the aspiration of Arp’s sculptural career. “I remember a discussion with Mondrian in which he distinguished between art and nature, saying that art is artificial and nature natural. I do not

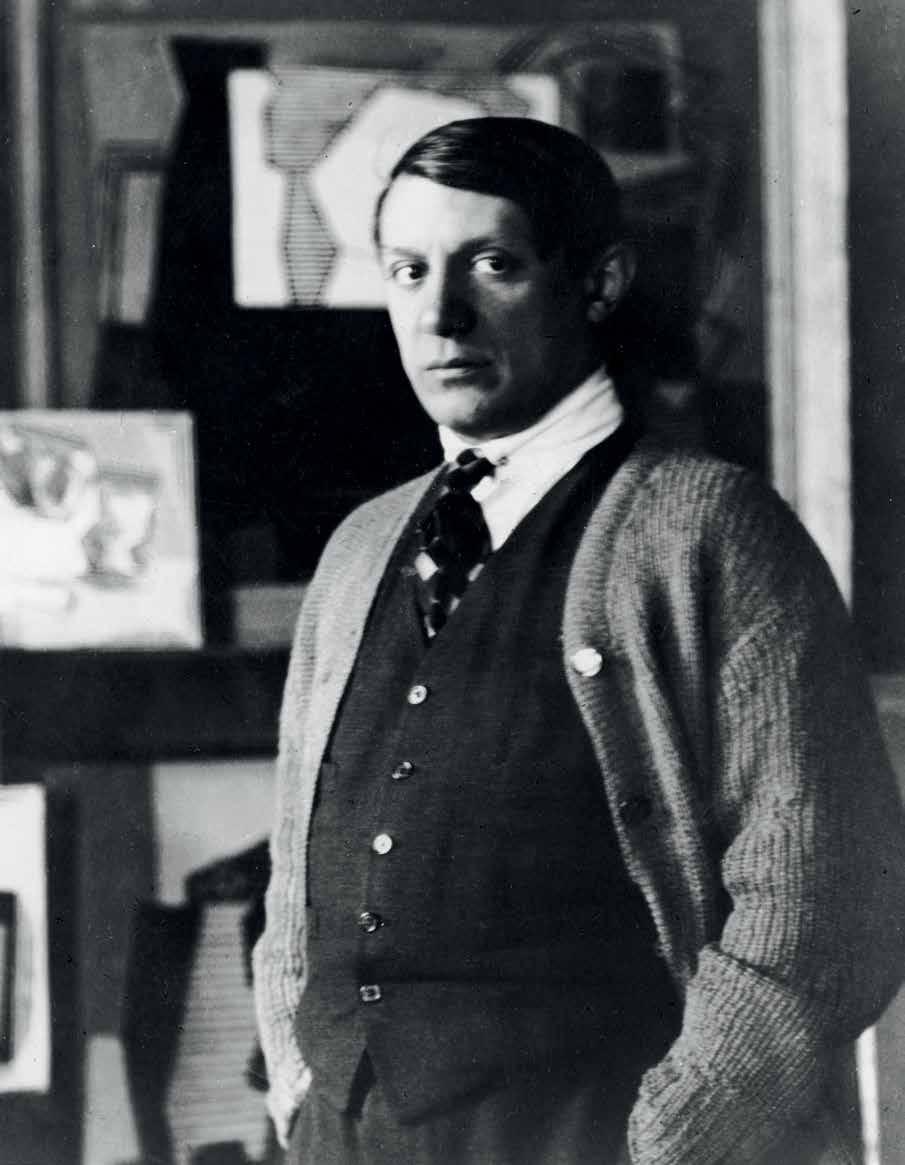

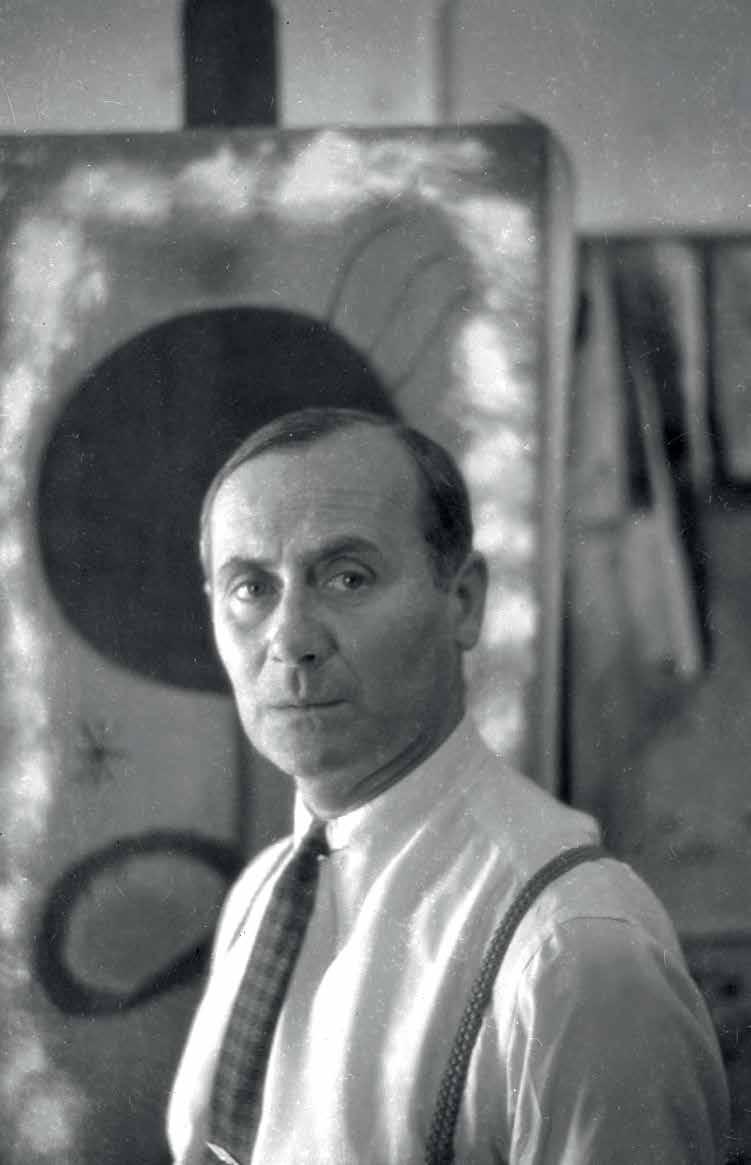

Jean Arp at his studio, Clamart, France, 1950.

Photo: Michel Sima / Bridgeman Images.

ART © 2022 Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Arp at his studio, Clamart, France, 1950.

Photo: Michel Sima / Bridgeman Images.

ART © 2022 Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

JEAN ARP, “L’ART EST UN FRUIT,” 1948, REPRINTED IN MARCEL JEAN, ED., JEAN (HANS) ARP: COLLECTED FRENCH WRITINGS, POEMS, ESSAYS, MEMORIES, LONDON, 1963, P. 241

VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 45

share this opinion,” Arp wrote. “I believe that nature is not in opposition to art. Art is of natural origin and is sublimated and spiritualized through the sublimation of man” (the artist in ibid., p. 241).

The natural essence of Fruit méchant is accentuated by Arp’s choice to render the sculpture in pink limestone, a choice which also lends a unique quality to the work within Arp’s predominantly bronze oeuvre. The speckling of the stone and its earthy tones give credence to the notion that it could have one day sprouted from the ground, while the inherently pitted surface gives the sculpture the air of having been weathered by the elements. The pink limestone here further serves to naturalize the sculptural elements of the form. In keeping with the notion that his sculpture should be integrated with nature just as any fruit, flower or stone would be, Arp did not conceive of Fruit méchant with a specific directional orientation in mind. In a letter to David Solinger from Arp’s wife Marguerite, she gives instructions as to how Arp intended for the sculpture to be displayed: “Bad fruit can be placed in different positions and so you can do best to make a base which allows these different positions… As it is a ‘fruit,’ Arp

had placed it in our home on a rather low base, a sort of bowl or plate.” She continues on to explain that at the time he created Fruit méchant Arp thought that his sculptures could work “as well off squatting on the corners of tables as nestling in the depths of the garden or staring at us from the wall,” and as such “need no specially conceived base but can be put as any other ‘objet’ where you like and on what you like.”

With the present work and those made contemporaneously, Arp radically reconceptualized the notion of the “naturalistic” sculpture, liberating it from the constraints of figuration. Prior to Arp, sculptors working in the naturalist style primarily took the human figure as their subject and sought to depict it with the utmost verisimilitude to life. Arp, however, contended that natural objects should be free from a fixed representational scheme, that they did not have to be a simulacrum of nature in order to be natural. In so doing, Arp opened the door for the trove of modernist sculptors who worked alongside and after him. It is this legacy, of naturalist modern sculpture, that makes Fruit méchant—and the body of Arp’s sculptural work that accompanies it—so revolutionary.

Left Pablo Picasso, Figures on the Seashore, 1931.

Image: Musee Picasso, Paris / Bridgeman Images. Art © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

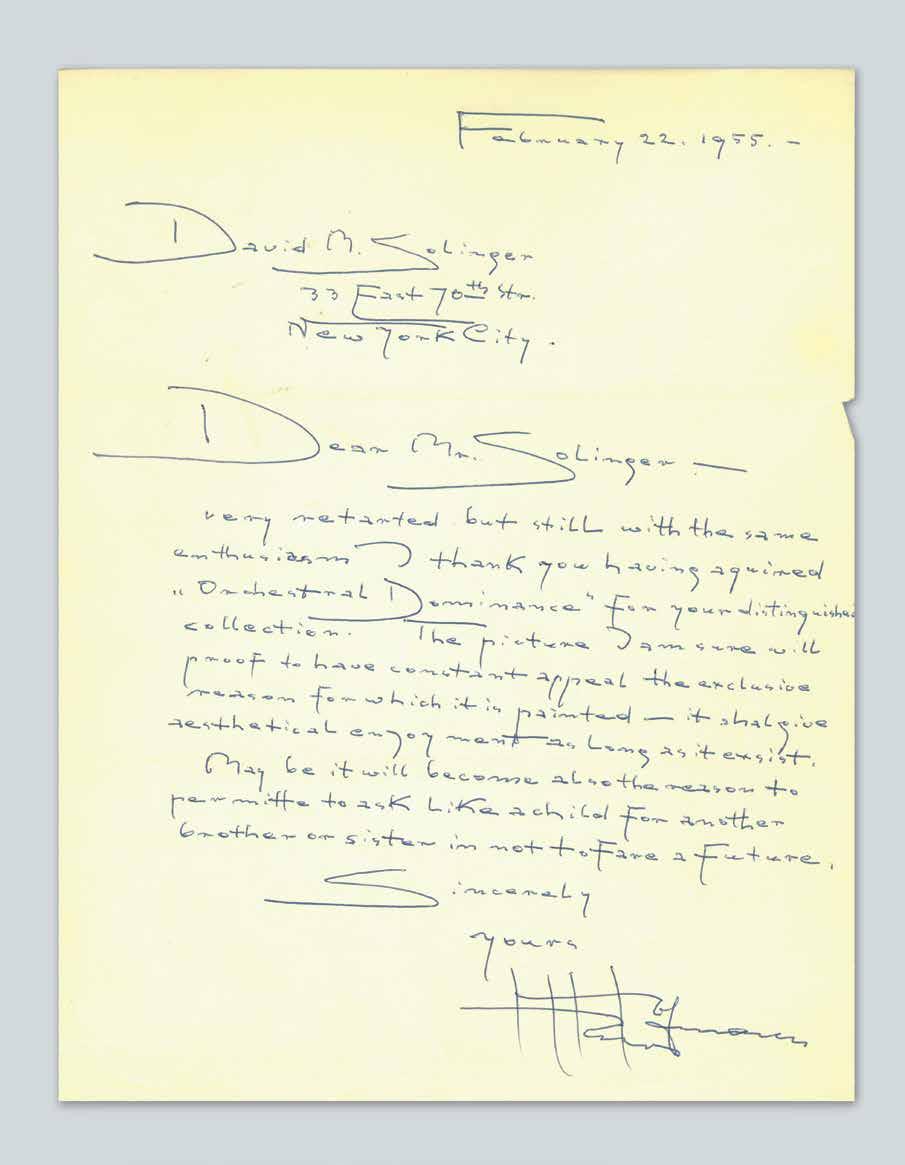

Opposite Letter from Marguerite Arp, the artist’s wife, to David M. Solinger describing the orientation of the present work, dated 1963

46 SOTHEBY’S

WILLIAM BAZIOTES

- 1963

Figures in Net

signed Baziotes (upper right) oil on canvas 24 ⅜ by 30 in. 61.9 by 76.2 cm. Executed in 1948.

$ 100,000-150,000

PROVENANCE

Samuel M. Kootz Gallery, New York Acquired from the above in September 1950 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Ithaca, Cornell University, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, The David M. Solinger Collection: Masterworks of Twentieth-Century Art, 2002-03, p. 23, illustrated

2

1912

48 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 49

“Baziotes’ paintings are the vivification of his life dedicated to the spirit so defined. Insheathed in an aura of wonderment, they speak of the torments of a mind at its highest emotional pitch, mining the rarest gemstones hidden deep within the psyche, working them through multiple layers toward the surface, reaching toward the light which glimmers faintly from the most distant star.”

BARBARA CAVALIERE CITED IN “WILLIAM BAZIOTES: THE SUBTLETY OF LIFE FOR THE ARTIST” IN EXH. CAT., NEWPORT HARBOR ART MUSEUM, WILLIAM BAZIOTES: A RETROSPECTIVE EXHIBITION, 1978, P. 27

Before a cerulean illusion of rippling aquatic depth, two amorphous figures emerge in William Baziotes’s Figures in Net from 1948, an ethereal example of the artist’s painterly penchant for the Abstract and Surrealist sublime. One of the most mysterious figures of the Abstract Expressionist circle working in New York at midcentury, Baziotes dedicated his painterly output to recreating dream-like states, often through biomorphic visual metaphors that resemble deep sea lifeforms or amoebic cells. Combining nature and artifact, organism and psyche, the present work perfectly expresses Baziotes’s artistic tendency for introspection and imagination as it invites the viewer to wander through its marine lattice in the profound search of a deeper truth.

In the 1930s, Baziotes frequently exhibited with a coterie of painters that included Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, and Robert Motherwell, all of whom dedicated their practice to principles of expressionism and abstraction. By 1940, however, when Baziotes befriended Roberto Matta, who introduced him to the tenets of European Surrealism, the artist began to espouse the psychic techniques of automatism, formulating them into his own abstractionist practice. Baziotes painted without prior compositional planning and instead manifested visuals from his wandering hand, unveiling and embracing the impulses of his subconscious. Seeking to intimate the phantoms of his own unconscious on canvas, Baziotes developed a rich visual lexicon of his own that was populated with the mythic yet organic biomorphic forms conjured from his imagination. As he reflected, “It is the mysterious that I love in painting. It is the stillness and the silence. I want my pictures to take effect very slowly, to obsess and to haunt” (the artist cited in “Notes on Painting,” It Is, 1959).

An intimately delicate composition, Figures in Net sees Baziotes move beyond the grand scale and action-based gestures of Abstract Expressionism: here, white curvilinear lines ellipse across the canvas in undulant routes, forming a “net” as the title suggests that sinks through shadowy depths into the melancholy background of murky indigo haze. Drifting

into focus before this atmosphere, two abstract elemental figures that luminate in ghostly white and bright yellow simultaneously recall oceanic creatures and otherworldly spirits. Fluid and ominous, the liquid movements of Baziotes’s brushwork in the present work seem to enter the quiet realm of dreams as they maneuver through the marine mysteries of the deep sea: as the artist states, “It is there when a few brushstrokes start me off on a labyrinthian journey that I am led to a more real reality” (t5he artist quoted in Exh. Cat., Newport Harbor Art Museum, William Baziotes: A Retrospective Exhibition, 1978, p. 44).

Executed at the apotheosis of Baziotes’s mature style in 1948, Figures in Net is a consummate example of the artist’s mystical and psychological practice that blends the fundamental tenets of both Abstract Expressionism and European Surrealism. In posthumous praise of Baziotes’s career, critic Grace Glueck wrote for the New York Times in 2001: “Baziotes seems to have reached the height of his powers in work from the mid-1940s to the late 1950s. His paintings from the mid-1930s…are more densely packed with colorful bits and pieces of monsters, animals, fish and arcane imaginings, tied together by webby lines. Their garrulous vivacity has its charms, but the later works, with sparer, more intense imagery, have a fluid, poetic eloquence that these busy early paintings lack” (Grace Glueck, “Art in Review; William Baziotes,” The New York Times, October 2001).

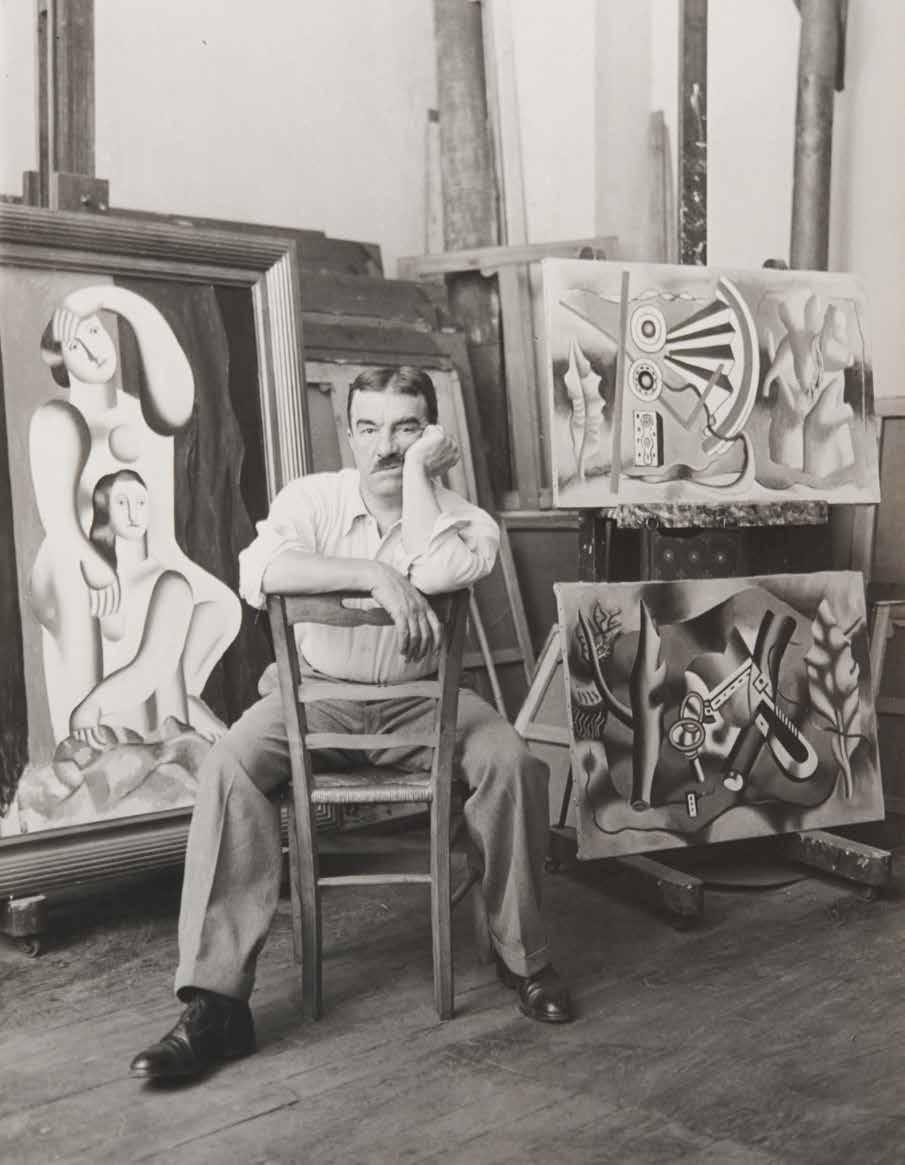

Left William Baziotes, circa 1947. Photo: Francis Lee / William and Ethel Baziotes papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Art © 2022 Estate of William Baziotes

Right Jean Arp, Étoile 1939.

Image: Israel Museum, Jerusalem / Bridgeman Images. Art © 2022 Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Following page Letter from “Bill” Baziotes to David Solinger, 7 July 1951

50 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 51

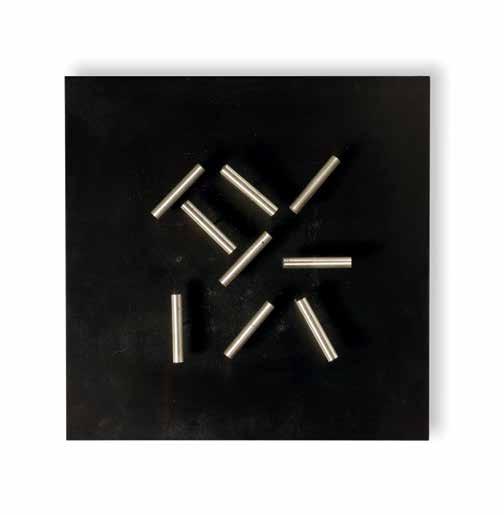

ALEXANDER

CALDER

1976

Sixteen Black with a Loop signed with the artist’s monogram (on the largest circular element) sheet metal, wire and paint 45 by 75 in. 114.3 by 190.5 cm. Executed in 1959. This work is registered in the archives of the Calder Foundation, New York, under application number A07539. $ 3,000,000-4,000,000

PROVENANCE

Perls Galleries, New York Acquired from the above in 1962 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Ithaca, Cornell University, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, The David M. Solinger Collection: Masterworks of Twentieth Century Art 2002-03, pp. 25-26, illustrated

3

1898

54 SOTHEBY’S

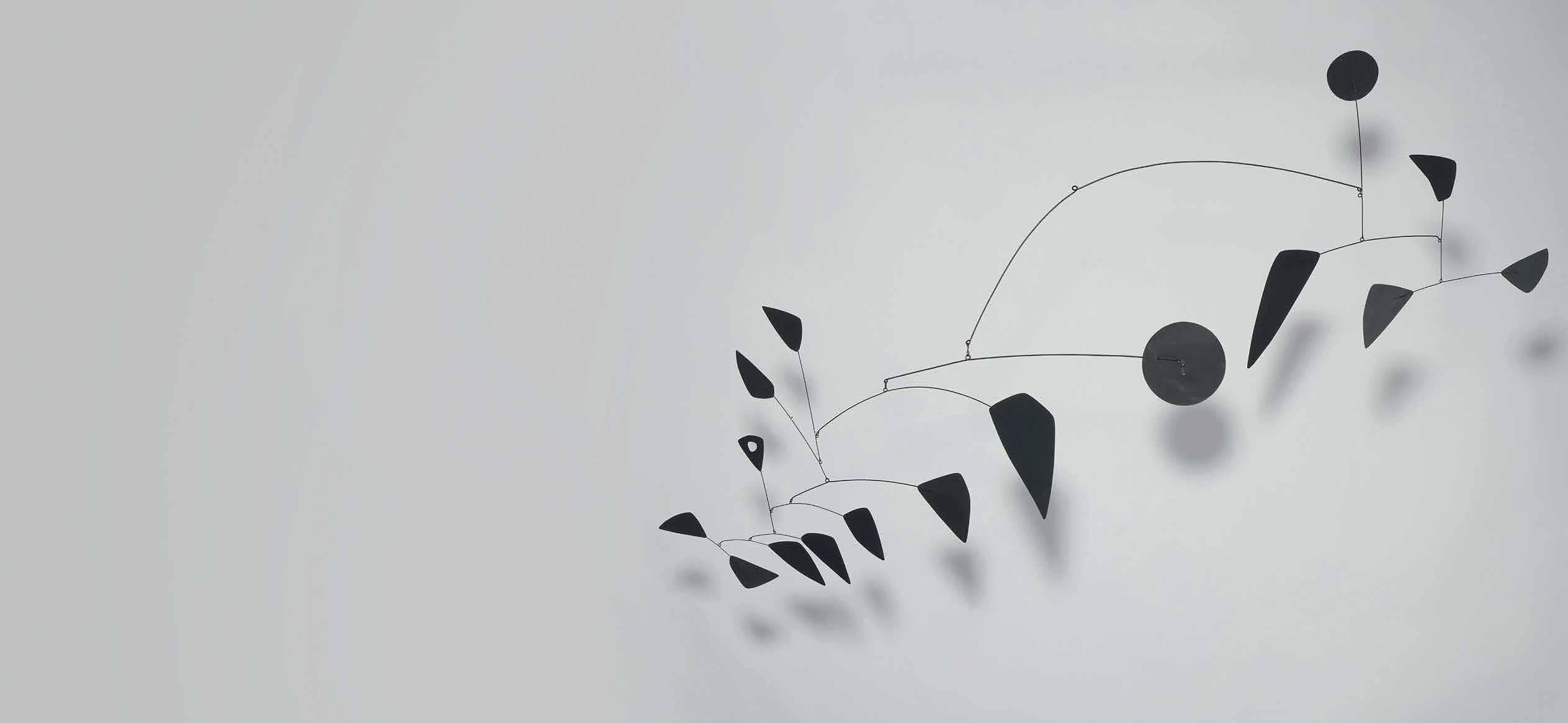

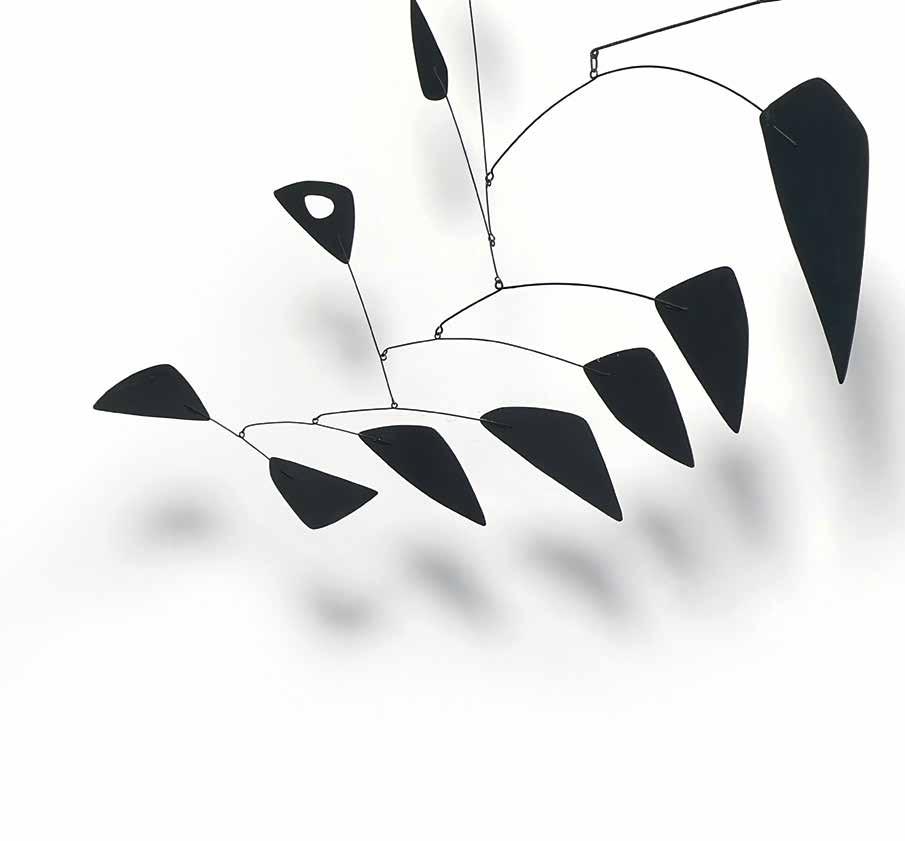

Asuperb example of Alexander Calder’s highly innovative, iconic mobiles of the mid-twentieth century, Sixteen Black with a Loop from 1959 poetically glides through the air, its many discrete elements balanced with both mechanical and aesthetic precision. The present work was created during a pivotal decade for the artist in which his achievements were acknowledged on a wide international scale. Acquired by the Solinger family in 1962 and remaining in their collection for six decades, Sixteen Black with a Loop is a coveted and magnificent example of Calder’s entrancing exploration of immateriality and abstraction.

As French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre elucidated in 1946, Calder’s mobiles spark wonder in the viewer; they are breathing, vitalized in a majestic way unlike any stationary sculpture: “They feed on the air, breathe it and take their life from the indistinct life of the atmosphere. Their mobility is, then, of a very particular kind. “ (JeanPaul Sartre in Exh. Cat., Paris, Galerie Louis Carré, Alexander Calder: Mobiles, Stabiles, Constellations

1946, translation by Chris Turner, The Aftermath of War: Jean-Paul Sartre Calcutta, 2008). Calder was the product of multiple generations of artists. His paternal grandfather and father both achieved great success creating heroic public monuments, and his mother was an accomplished painter. Calder created art throughout his childhood, and he was always given a workshop when the family moved around the country for his father’s commissions. In 1923, after deciding to become a painter, Calder would dedicate himself solely to art, taking courses at the Arts Students League and traveling frequently between the United States and France into the next decade. During his transatlantic artistic development, Calder established himself deeply within the European art scene, making important ties with several notable artists, including Joan Miró, Fernand Léger, Jean Arp, and Marcel Duchamp. In 1930, Calder made a visit to Mondrian’s home that he would later mark as a watershed moment in his career. Mondrian’s studio environment greatly impressed Calder, galvanizing the artist to devote much of the

Pull out Alexander Calder in his studio in Roxbury, Connecticut, 1958. Photo: Phillip Harrington / Alamy Stock Photo.

Alexander Calder in his Roxbury, Connecticut studio, 1957. Photo © Arnold Newman / Getty Images. Art © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Surely the elusive movements of Calder’s greatest mobiles of the 1940s and 50s are echoes or afterimages—if not indeed embodiments—of The Invisible”

EXH. CAT., LOS ANGELES COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART, CALDER AND ABSTRACTION FROM AVANT-GARDE TO ICONIC 2013, P. 41

VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 57

remainder of his career to abstraction. Just two years later, Calder famously remarked: “Why must art be static?... You look at an abstraction, sculptured or painted, an intensely exciting arrangement of planes, spheres, nuclei, entirely without meaning. It would be perfect, but it is always still. The next step in sculpture is motion” (Alexander Calder quoted in Howard Greenfield, The Essential Alexander Calder New York, 2003, p. 67). Over the subsequent four decades, until his death in 1976, Calder investigated the concept of enlivened sculpture, creating moving works that Duchamp termed “mobiles” in 1931. Calder’s completely ingenious studies of volume, time, and space solidified his role not only as a pioneer of Kinetic Art, but also as a paramount artist of the twentieth century.

The present work is composed of sixteen elegantly balanced sheet metal elements, stretching across an impressive six feet and suspended in the air, weightless yet animated. Fourteen of these pieces are unique, angular

forms, each positioned to comprise an optimal compositional arrangement and practical interaction with wind and air. At the apex of Sixteen Black with a Loop, stretching up above the other fifteen elements, presides a perfect, circular form. Solar in its presence, this feature is the focal point of the sculpture, the center of a radiating orbit. Organized in a graceful cascade, the other metal components delicately and harmoniously swirl in the air around one another. For the first time in the 1940s, Calder began to perforate some of the elements in his composition, like he has done for just a single one in the present work. This pierced segment juts out in perfect balance with the other components of the mobile. Its ovular perforation echoes the two circular elements in the mobile, guiding the viewer’s gaze and enhancing the unity of the composition. Perpetually encircling itself and rotating on its central axis, the mobile encourages the viewer to circumambulate it and even observe it reverently from below.

Previous page

Letter from “Sandy” Calder to David Solinger, inviting him to visit for lunch, and a hand-drawn map of directions to his home, 5 December 1961

Above

Joan Miró, The Nightingale’s song at Midnight and Morning rain 1940. Image: Private Collection / Bridgeman Images. Art © 2022 Joan Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Engineered to be seamlessly powered by the circulation of air in space, Calder’s mobiles unify the natural world with the human made, simultaneously the product of basic principles of airflow and human ingenuity. Debasing the accepted conception of sculpture as a necessarily stationary art form, Calder developed his own manifestation of kinetic, seemingly living sculpture. Calder’s mobiles activate the surrounding air, becoming visible encapsulations of the intangible natural phenomena that govern our living world. Art historian Jed Perl has described, “Surely the elusive movements of Calder’s greatest mobiles of the 1940s and 50s are echoes or afterimages— if not indeed embodiments—of the invisible” (Exh. Cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Calder and Abstraction from Avant-garde to Iconic 2013, p. 41).

While Calder’s hanging mobiles do embody certain characteristics of traditional sculpture, they also importantly eradicate one of its most

limiting aspects: a base or pedestal. Suspended from the ceiling, Calder’s hanging apparatuses do not require support from below. The mobiles rotate on multiple axes at once, perennially changing in composition and transcending static three-dimensionality. Observed by James Johnson Sweeney in the 1930s, “A new means to organize three-dimensional space was the search to which Calder as a sculptor was always returning” (Exh. Cat., New York, Museum of Modern Art, Alexander Calder, 1951, p. 56). Calder’s works not only innovatively investigate sculpture but also uniquely engage with a fourth dimension: time. Poetically dancing on its axis, Sixteen Black with a Loop is a delicate yet bold example of Calder’s intuitive investigation. Using simple cut metal and wire, Calder challenged the status quo of contemporary sculpture, revolutionizing the presupposed role and social function of the discipline. Eclipsing existing standards of contemporary art, Calder produced aesthetic and mechanical perfection in his mobiles.

60 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 61

JOAN MIRÓ

1893 - 1983

Femme, étoiles

signed Miró, dated 7-5-45 and titled (on the reverse) oil on canvas

44 ½ by 57 ¾ in. 114 by 146 cm.

Executed in Barcelona on 7 May 1945.

$ 15,000,000-20,000,000

PROVENANCE

Galerie Pierre, Paris

Galerie Maeght, Paris

Acquired from the above in 1951 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

Paris, Galerie Maeght, Joan Miró 1948, no. 63 (titled Femme et étoiles

Stockholm, Galerie Blanche, Joan Miró målningar, keramik, litografier 1949, no. 6 (titled Femme, étoile

Ithaca, Cornell University, Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Contemporary Painting and Sculpture from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. David M. Solinger 1956, no. 16 (titled Woman and Stars

New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Joan Miró, 199394, no. 179, p. 268, illustrated in color

Ithaca, New York, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, The David M. Solinger Collection: Masterworks of Twentieth-Century Art 2002-03, p. 117, illustrated in color

LITERATURE

Tristan Tzara, “Pour passer le temps…,” Cahiers d’art vols. 20-21, Paris, 1945-46, p. 288, illustrated (titled Femme et étoiles)

Jacques Dupin, Miró, Life and Work New York, 1962, no. 656, p. 550, illustrated (titled Woman, Star

Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró: Catalogue Raisonne: Paintings, vol. III, Paris, 2001, no. 756, p. 80, illustrated

4

62 SOTHEBY’S

“Miró let go with the full range of his powers, showing us what he could really do all the time. Anywhere outside the world, and outside time, too—his voice echoes everywhere and always, a voice carried to us from afar, to join the chorus of the loftiest, most inspired voices the world has ever heard.”

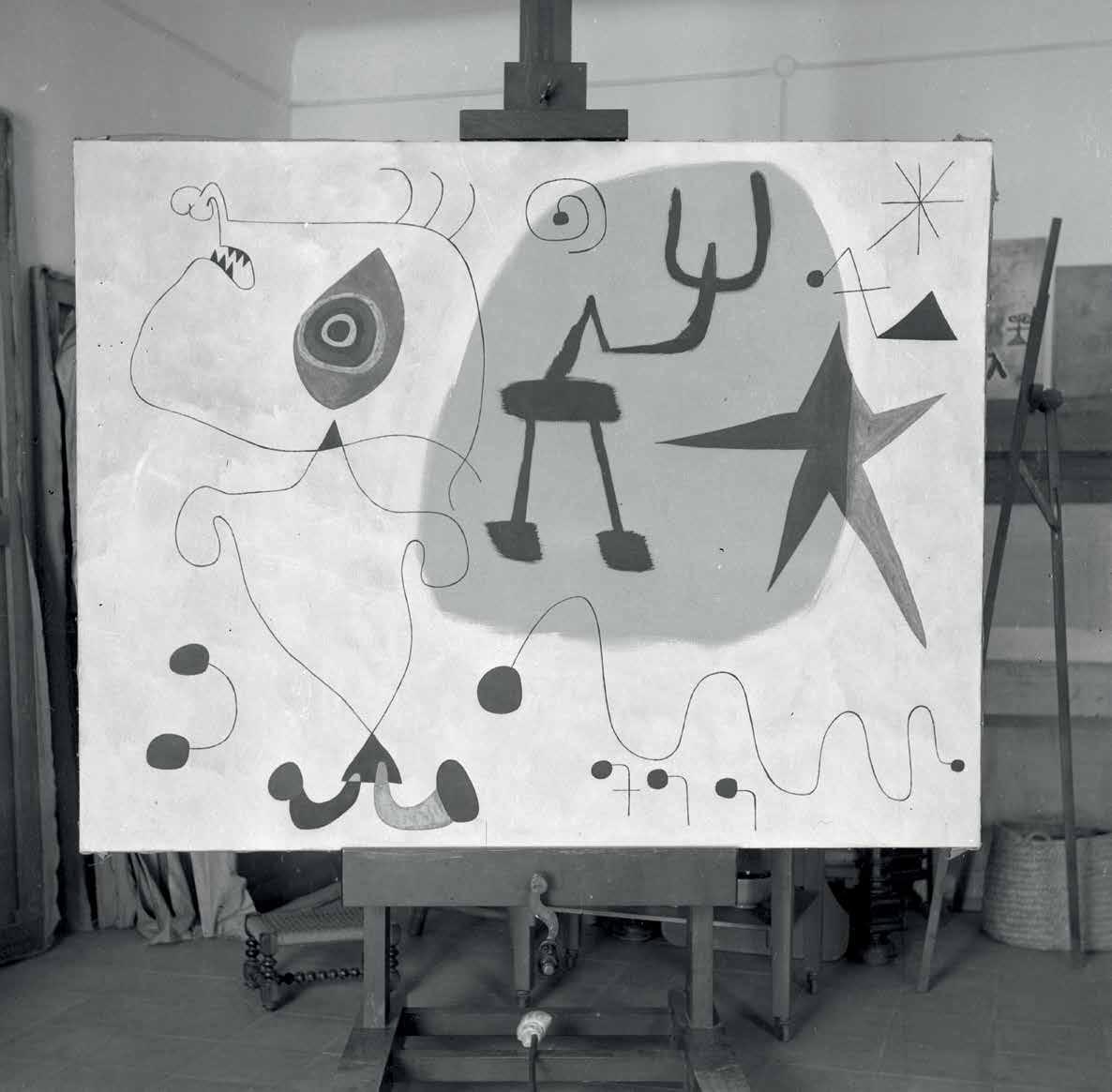

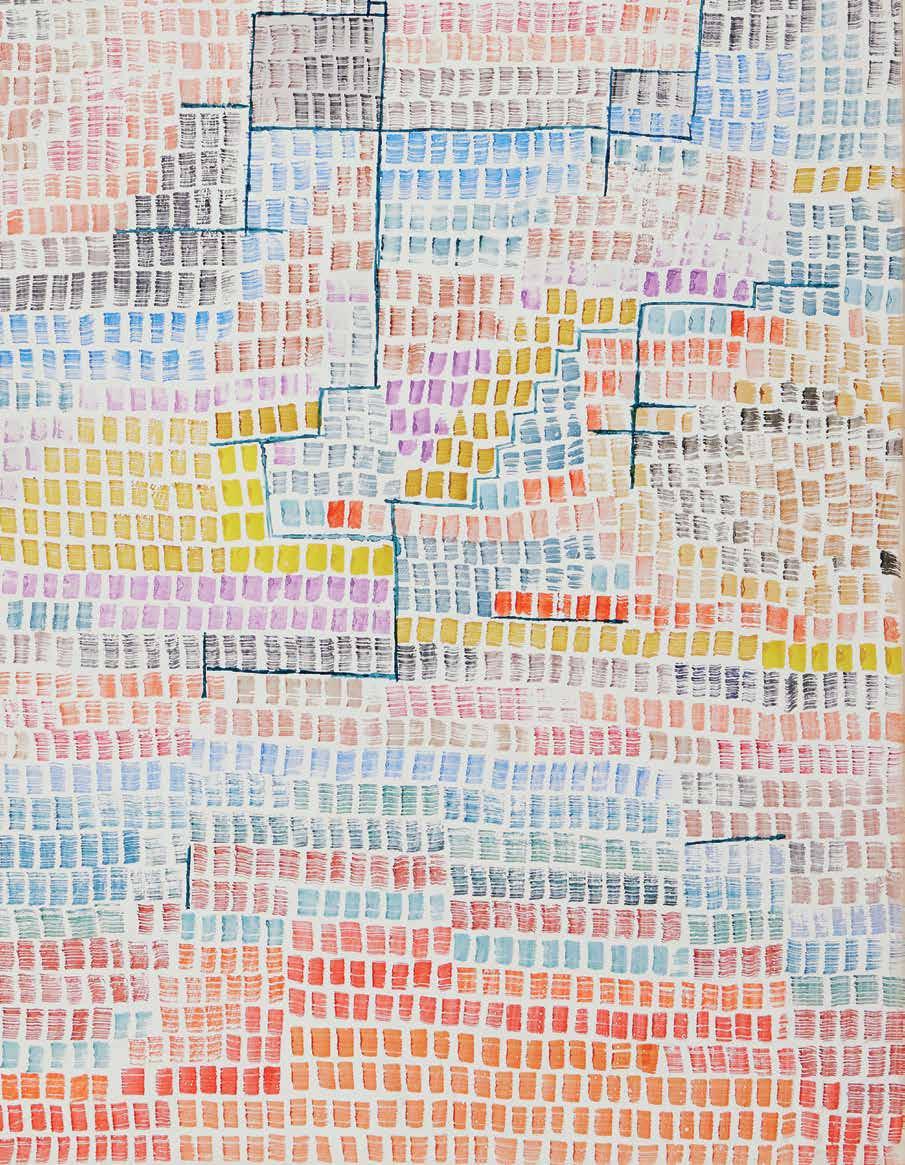

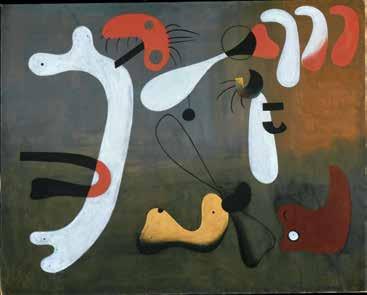

Apoetic array of Joan Miró’s greatest motifs, Femme, étoiles can be viewed as a culminating opus of its era, chronicling the end of the Second World War and serving as a coda to the masterful Constellations begun at its onset. Of the related works from 1945, there is perhaps no other painting with more historical significance than Femme, étoiles. Painted on the 7th of May 1945, the present work marks he very day that the German High Command signed an unconditional surrender at Reims, marking a long-awaited and momentous end to the world’s deadliest war. Imbued with the import of the moment, Femme, étoiles presents an inherent dichotomy which speaks to horror of conflict and the hope of freedom; with the composition’s dueling expanses of light and dark, the alternately placid and menacing figures and the balance of heavy and fine lines, the elements within Femme, étoiles coalesce to create a work at once enveloping and anticipatory, expressing an excruciating lyricism rife with the poetics of tragedy and comity.

A favored cast of characters from Miró’s visual lexicon appear in the present composition as an anthropomorphic figure of a woman floats at left, seemingly emanating from a grey portal at right.

Varied stars and mellifluent lines dance across the surface, achieving a paradoxical balance of motion and stasis within the scene. Beholding the power of Miró’s work, one has the feeling of emerging from the long dark of night, headed at last toward a brilliant new dawn of possibility.

Engendered by the defining Constellations series begun in 1940, Femme, étoiles inherits the legacy of the iconic body of twenty-three works considered by Miró at the time to be “one of the most important things I have done” (quoted in Margit Rowell, ed., Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews, Boston, 1986, p. 168). As the name of the series implies, the works belonging to Miró’s Constellations are often set against a background of muted washes and darker tones evoking the night sky and providing a context for the abundant forms of women, birds and stars that mingle within them.

Miró began working on the watershed gouache compositions in January 1940 in the quiet northern French village of Varengeville, where he had settled after leaving his home country at the onset of The Spanish Civil War.

Like his fellow countryman Picasso, Miró’s most famed works would be defined in relation to shifts in the world order. At the Spanish Pavilion of the 1937 World’s Fair both painters present distinctly anti-war paintings on a monumental scale; Picasso’s revolutionary Guernica and Miró’s Le Faucheur.

By May 1940, Miró was again forced to relocate, this time back to Spain due to the German invasion of Paris. By the time his Constellations were done, the artist had moved to Mallorca (careful at first to avoid his native Catalonia out of fear of Francisco Franco’s secret police) and then to his family’s home at Montroig. Amid all the upheaval Miró found solace in his

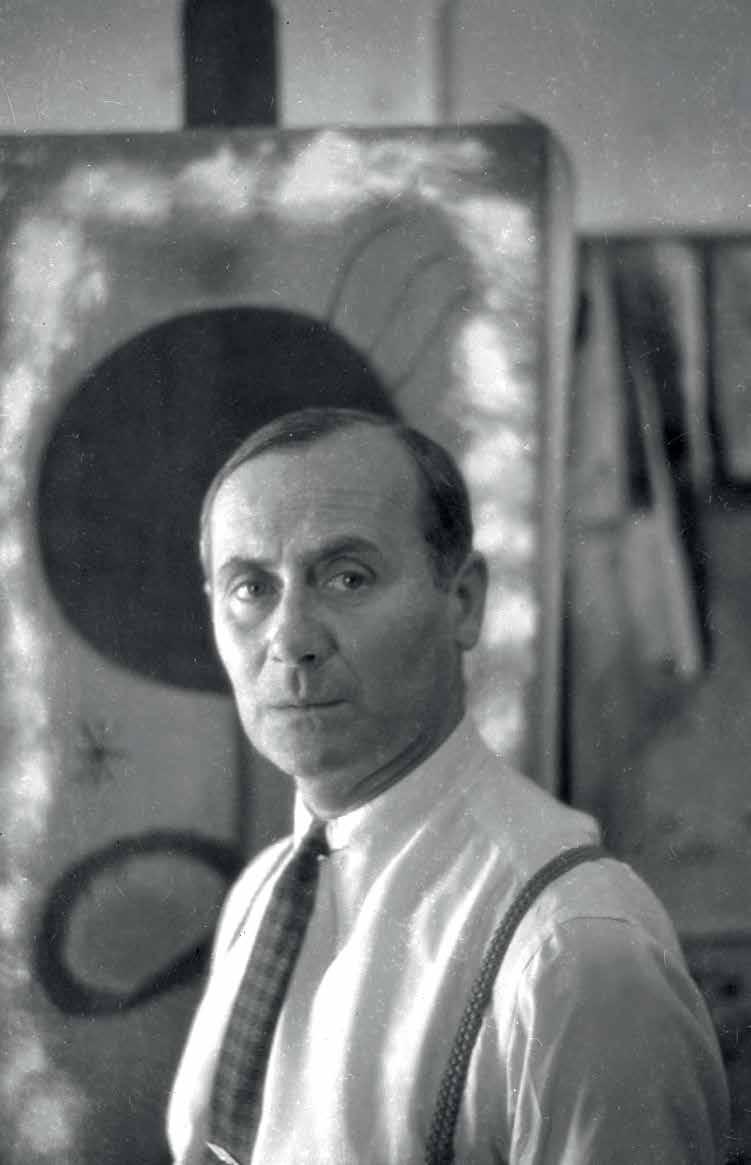

Joan Miró with a related work from the series, Femme dans la nuit painted March 1945; now in the collection of The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photograph by Sanford Roth. Courtesy of Scott Nichols Gallery, Sonoma, California Art © 2022 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

ANDRÉ BRETON CIRCA 1945, QUOTED IN JACQUES DUPIN, JOAN MIRÓ, LIFE AND WORK NEW YORK, 1962, P. 360.

64 SOTHEBY’S

art, stating in an interview with James Johnson Sweeney that “It was about the time that the war broke out. I felt a desire to escape. I closed myself within myself purposely. The night, the music, and the stars began to play a major role in suggesting my paintings” (quoted in Janis Mink, Joan Miró: 1893-1983 Cologne, 1993, p. 67).

Such fonts of inspiration carried on in the following years after Miró’s first major retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1941 and his subsequent relocation to Barcelona in 1942, where, after months of careful dedication to his Constellations, Miró let his

imagination take flight in hundreds of unbridled and diverse works on paper centered around the theme of women, birds and stars. It was not until 1944 that he again took up oil painting, committing to an authority and decisiveness that the medium commanded.

At the same time that Miró’s Constellations opened to critical acclaim at Pierre Matisse’s gallery in New York in early 1945, the artist embarked upon yet another defining series which would translate the idols of his earlier gouache masterpieces into indelible large-scale canvases like Femme, étoiles.

The present work installed in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1993 Joan Miró retrospective. Paintings from left to right: Danseuse entendant jouer de l’orgue dans une cathédrale gothique 26 May 1945 (Fukuoka Art Museum, Japan); Femme entendant de la musique (Private Collection); The present work. Art © 2022 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Discussing the significance of the artist’s work from this period, Jacques Dupin states, “The intimism of Miró’s entire production from 1939 on, and the invention of a new language which it made possible, lead to a magnificent series of large canvases painted in 1945, which are among the best-known and most frequently reproduced of all his works” (Jacques Dupin, Joan Miró, Life and Work New York, 1962, pp. 378). On the iconography of Miró’s 1945 works, Dupin continues, “The space is taken up with big figures, birds, stars, and signs…No signs could be simpler, yet they are constantly renewed from one canvas

to the next, in strict obedience to mysterious laws governing their dimensions, number, direction, and distribution…The forms are, in the artist’s own words, ‘at once mobile and immobile.’ ‘What I am looking for,’ Miró also said, ‘is a motionless movement, something equivalent to what is called “an eloquent silence” or what St. John of the Cross referred to as muted music’” (ibid., pp. 379-80).

Of the eighteen other canvases in this remarkable series, ten are in museum collections including The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Fundació

Joan Miró in Barcelona, among others. Painted on roughly the same scale (typically between 57 and 63 inches in the largest direction), the canvases from 1945 feature an evolution of female figures in the night. The first half of the series is dominated by playful figures and connected black dots against soft white grounds in horizontal format. The execution of the present work in May marks a turning point within the series, the grounds becoming increasingly modulated and rich in color. For the first time, the large orb of

grey encircles a black two-legged form—a feature which would carry over into the following two canvases from that month. Suddenly the main protagonist, ostensibly the namesake woman, bears a small set of sharp teeth, another motif which would in part define the remaining works of the series. While the impact of the composition on the whole is one of resounding eloquence, even calm, there exists a faint echo of antagonism; though the war had come to an end in Europe, the harsh realities of General Franco’s fascist reign in Spain remained.

In addition to the important gallery shows in Paris and Stockholm in the late 1940s, Femme, étoiles was notably featured at The Museum of Modern Art’s historic centennial exhibition dedicated to Miró’s legacy where it hung beside related works from the series and the fantastical sculptures that such paintings inspired.

Left

Left

The present work installed in Miró’s studio, 1945. Photo © Hereus de Joaquim Gomis / Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, 2022. Art © 2022 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya, Barcelona Above Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. Image: Succession Picasso / Bridgeman Images. Art © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

69

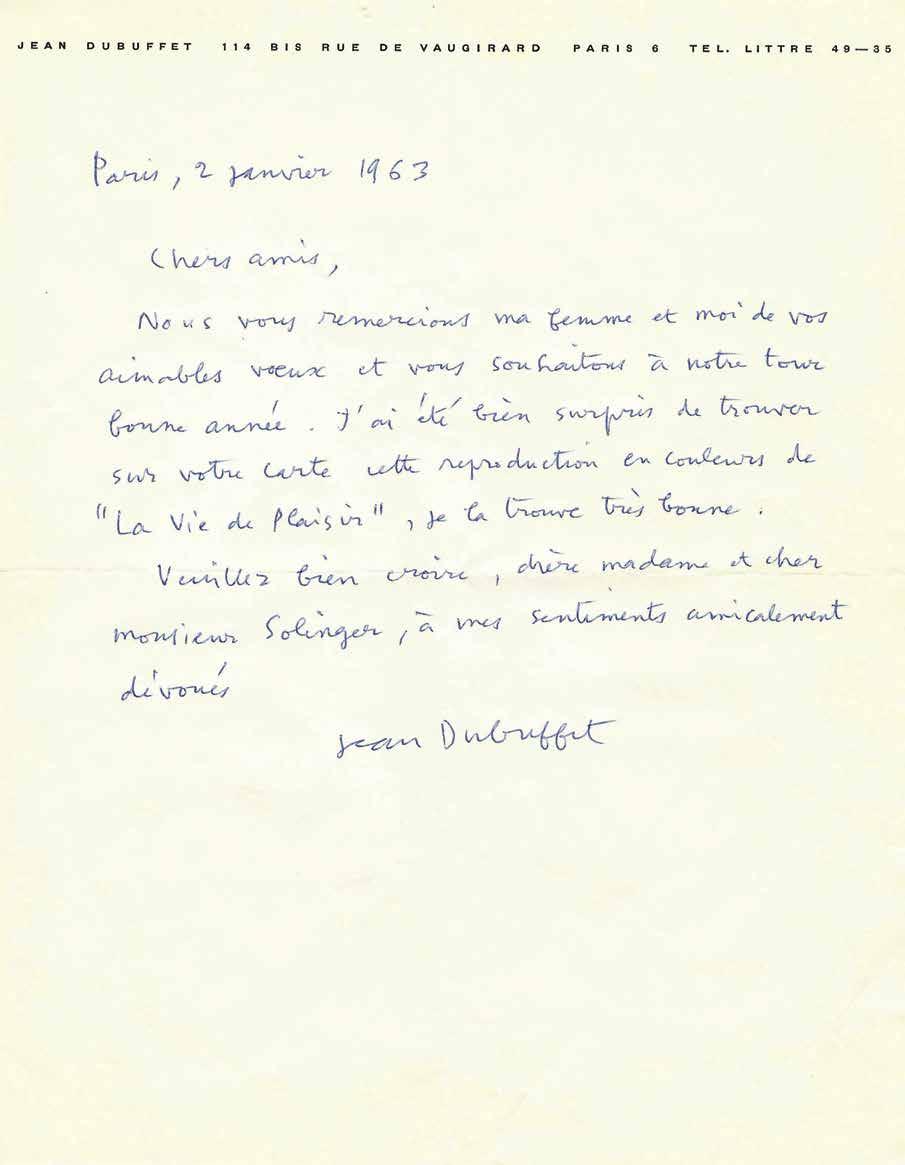

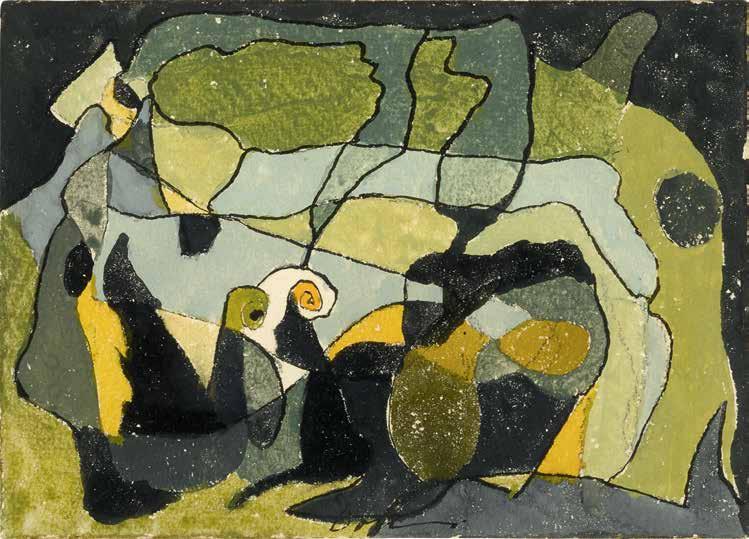

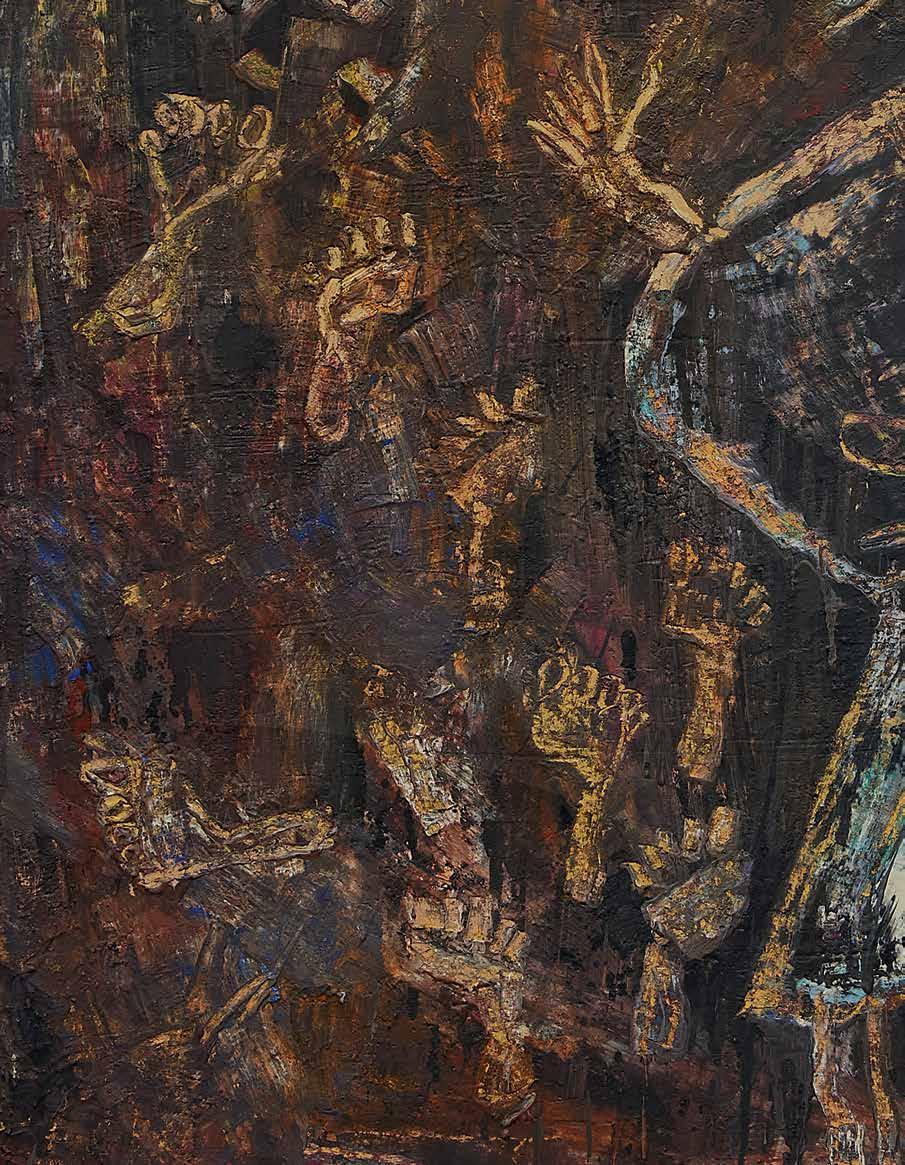

BELOW AND BEYOND THE HORIZON JEAN DUBUFFET IN THE DAVID M. SOLINGER COLLECTION

ELEANOR NAIRNE

ELEANOR NAIRNE

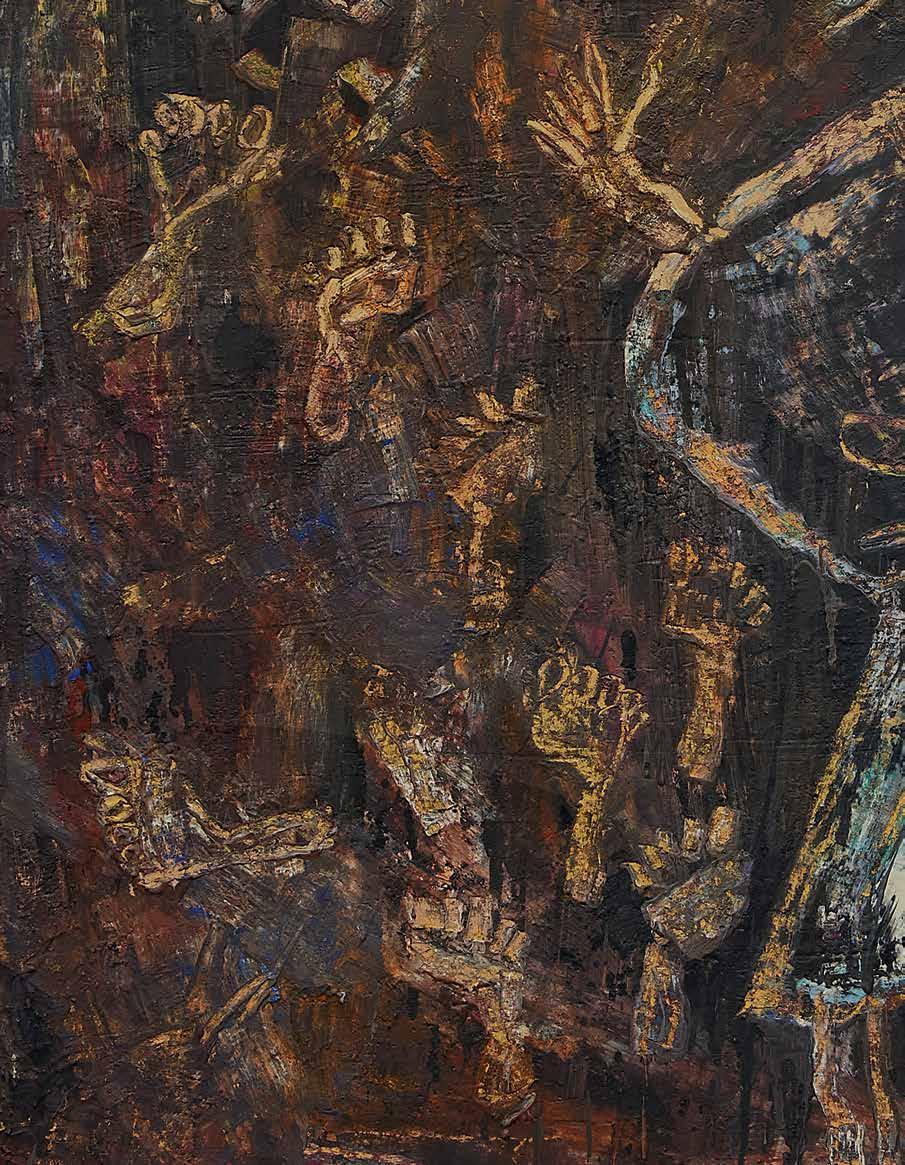

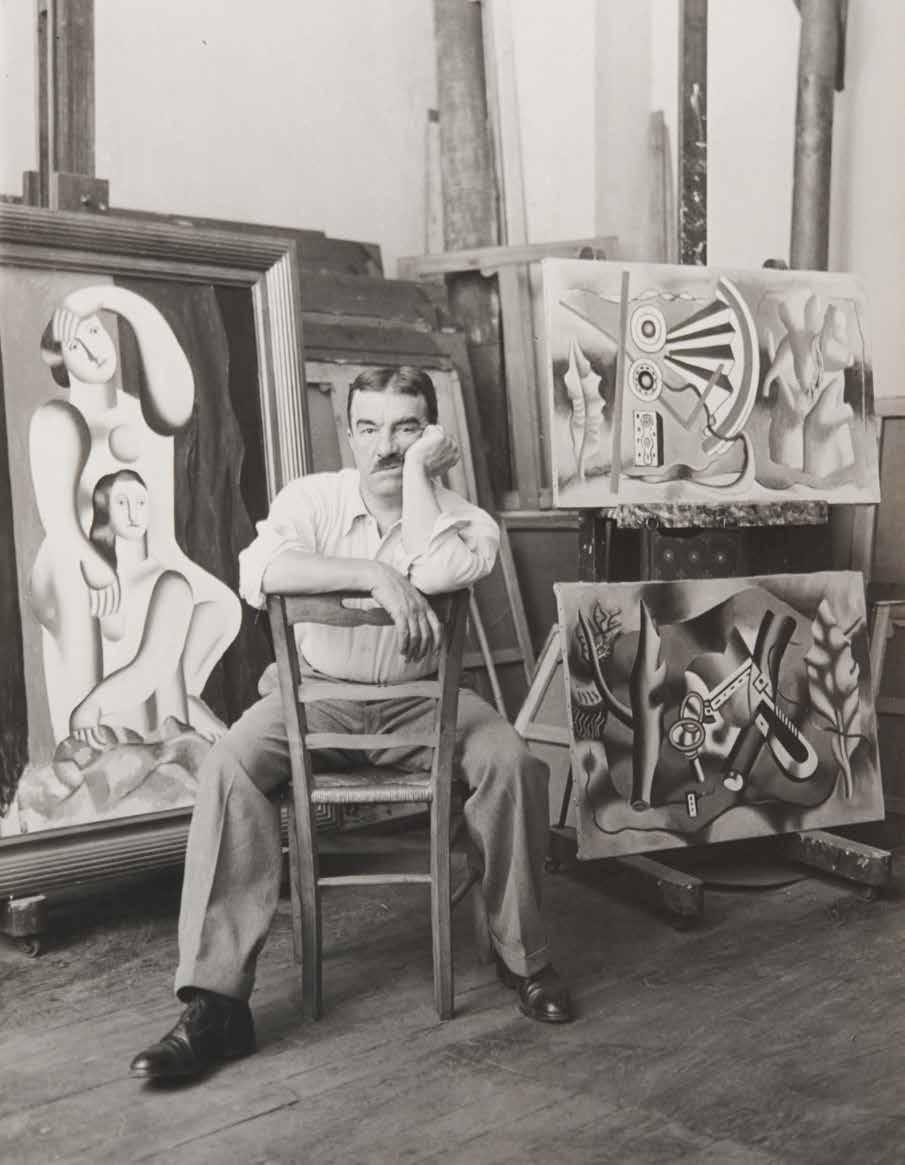

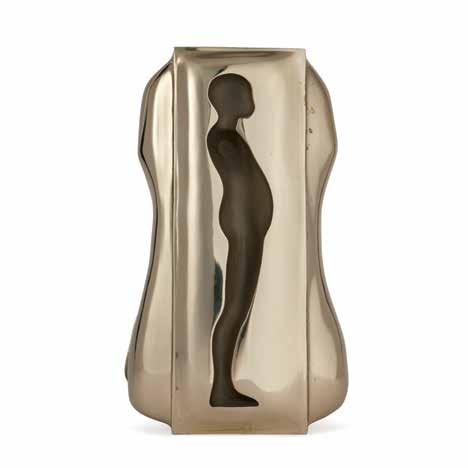

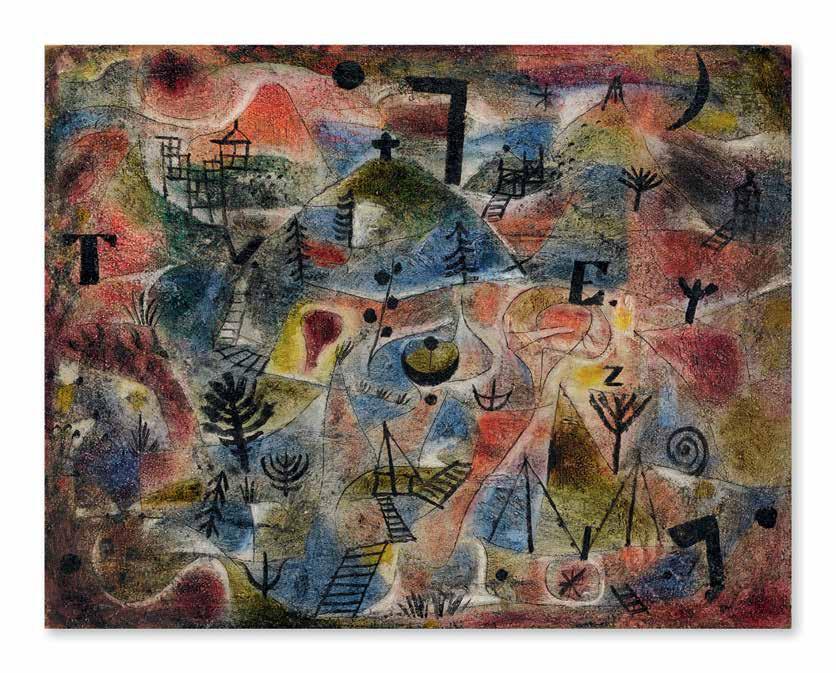

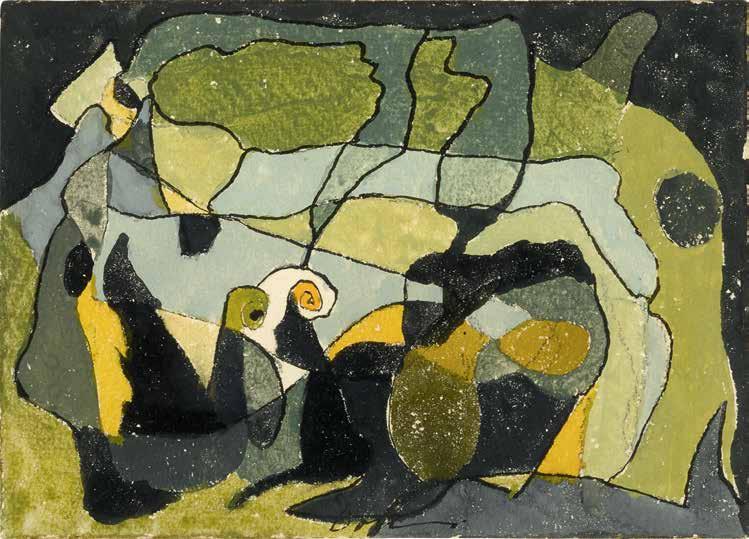

According to the traditions of composition, an artist should place their horizon line one or two thirds from the base of the canvas. For the postwar provocateur Jean Dubuffet, this was a cardinal rule to be ruptured: he made his ground rise up to the brink of threatening to eclipse the sky and sink his canvas. Brume du matin sur la campagne, 1945, has only the skimpiest ribbon of vivid blue above the hazy countryside, while Scène dans un paysage de rochers ou trois malandrins dans les rochers, from the following year, has a band of navy so narrow and close in hue to the murky backdrop of the highwayman that a casual look might not discern it. By the summer of 1948, in Chamelier, this kind of sliver had been exaggerated into a signature device – used to offset the churning land below.

Dubuffet’s aim was radically simple: to return us to the earth and, in doing so, to remind us of the organic continuity between our feet and the ground beneath them. Looking at the two figures gambolling across the mass of wine-dark paint in Prompt Messager from 1954, I think of the character of Joane in Clarice Lispector’s first novel Near to the Wild Heart from 1943. ‘There were many good feelings. Climbing the hill, stopping at the top and, without looking, feeling the ground covered behind her, the farm in the distance. The wind ruffling her clothes, her hair. Her arms free, heart closing and opening wildly, but her face bright and serene under the sun. And knowing above all that the earth beneath her feet was so deep and so secret that she need not fear the invasion of understanding dissolving its mystery. This feeling had a quality of glory.’1

Clarice Lispector, Near to the Wild Heart (London: Penguin Classics), p. 36. Lispector took her title from James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: ‘He was alone. He was unheeded, happy, and near to the wild heart of life’.

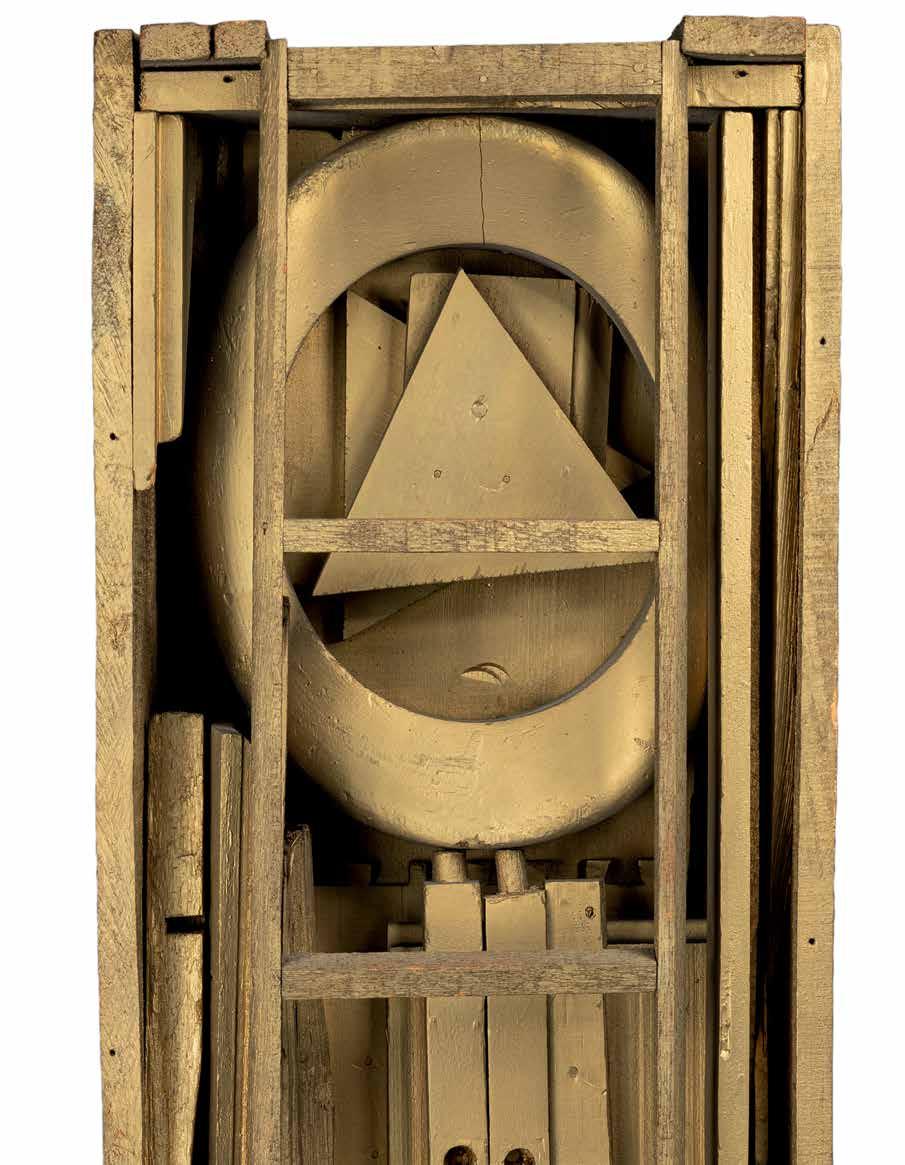

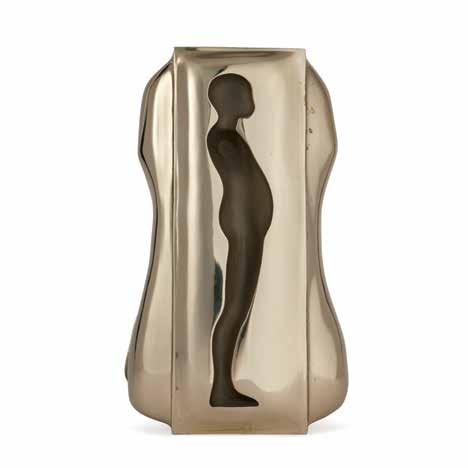

Lot 5, Jean Dubuffet, Scène dans un paysage de rochers; Maurice Estève, Maréchal-Ferrant, The David M. Solinger Collection, Sotheby’s Paris, December 2022; and a selection of Pre-Columbian and Mezcala figures to be offered Sotheby’s New York, Art of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, 22 November 2022

Photo © Visko Hatfield

73

When Dubuffet had his first solo exhibition at Galerie René Drouin on the Place Vendôme in Paris in October 1944, Jean Paulhan wrote a letter for the catalogue, delighting in the fact that his friend’s ‘paintings were not at all a ministry, nor a theorem, but a sort of rejoicing, something like a public celebration’.5 In fact, visitors were not sure how to respond to his crude imagery, which must have felt like the rudest interruption into the particularly French history of la belle peinture Some even staged protests outside the gallery –which only spurred the artist on. His fundamental commitment was to matière, as the base truth to all existence; ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Lispector was just 23 years old when she published her blazing novel, leaving Brazilian critics to grapple with what one called her ‘bewildering verbal richness’.2 Dubuffet was nearly twice her age by the time he committed to being an artist (after a successful career as a wine merchant) but he shared many of her interests in breaking traditional idioms in order to ‘surprise the symbol of the thing in the thing itself’.3 Or to put it another way: what if a seemingly childlike image of a craggy landscape, with sand and gravel embedded into the very paint, had a better chance of rendering its qualities than any picturesque easel painting could hope to?

‘Grope your way backwards!’ Dubuffet liked to exclaim; amateurism made a new kind of sense in the wake of the barbarity of the Second World War, which so thoroughly discredited western notions of human rationalism and civility.4

Opposite Cover of the exhibition catalogue, Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, 1947

Cover of the exhibition catalogue, Mirobolus, Macadam et Cie Rene Drouin, Paris, 1946

Above Jean Dubuffet, Brume du matin sur la campagne The David M. Solinger Collection, Sotheby’s Paris, December 2022

A photograph of Dubuffet in his studio in 1951 by Robert Doisneau, makes him look like more like an eccentric cook than an artist – with pots and pans and palette knives at the ready to ice his latest creation. Gastronomical metaphors were at home in Dubuffet’s writing. As a man who railed against specious intellectualism, he felt more at ease comparing his work to provisions than Picasso. ‘Let the artist’s mind, his moods and impressions, be offered raw, with their smells still vivid, just as you eat a herring without cooking it, but right after pulling it from the sea, when it’s still dripping,’ he encouraged. He was equally fond of animalistic imagery. Indeed, the hautes pâtes, of which the three highwayman is a prime example, were infamous for taking on a life of their own. In his catalogue essay for Mirobolus, Macadam et Cie at the Galerie René Drouin in 1946, Michel Tapié wrote of ‘one painting, over the course of an entire night [which] spat all over the harmonium… Dubuffet enjoys these adventures enormously, calling them “hippopotamus perspiration”’.7

Benjamin Moser, ‘Hurricane Clarice’, Near to the Wild Heart xi Moser, ‘Hurricane Clarice’, Near to the Wild Heart xi Jean Dubuffet, ‘Notes for the Well-Read’ [‘Notes pour les fins-lettrés’, 1945], trans. Joachim Neugroschel in Mildred Glimcher, Jean Dubuffet: Towards an Alternate Reality (New York: Pace Publications / Abbeville Press, 1987), p. 67.

Jean Paulhan, Letter to Jean Dubuffet in Exposition de tableaux et dessins de Jean Dubuffet exh cat, Galerie René Drouin, Paris, 1944, n.p. Dubuffet, ‘Notes for the Well-Read’, p. 77.

Michel Tapié, ‘Mirobolus, Macadam et cie: hautes pâtes de J. Dubuffet’, reprinted in Catalogue des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, vol. 2, ed Max Loreau (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1966), p. 119.

74 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 75

Opposite Jean Dubuffet in his Paris studio, 1951.

Photo © Robert Doisneau/GammaRapho/Getty Images.

Art © 2022 Fondation Dubuffet, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

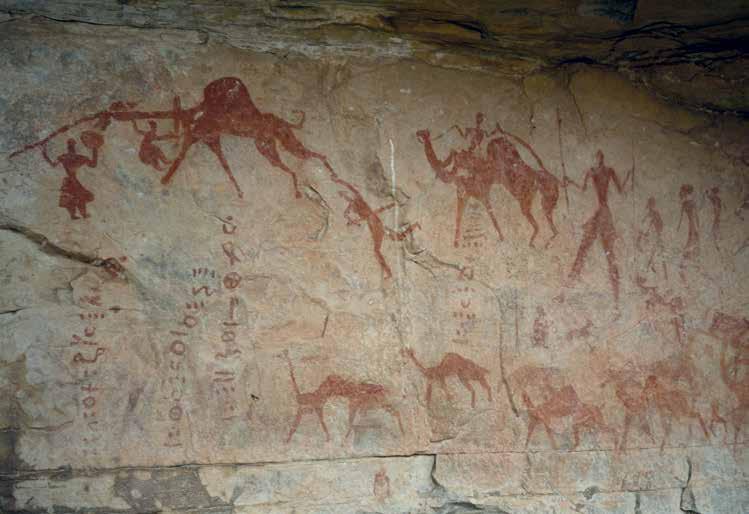

The anecdote speaks to Dubuffet’s essential concern with how he could use humble materials (household paint, asphalt, glue, shards of glass, frayed string, coal dust and so on) to make his pictures teem with life. After the fields that were destroyed by battles, how could an artist paint a landscape any other way? Dubuffet worked with his canvas or board directly on the floor of his studio so that it had a literal relationship to baseness; he used a kind of putty to build a tactile relief onto the surface to create ambivalence about whether we are looking at a cross-section of a landscape or an aerial view. As part of his search for new perspectives, Dubuffet made three extended trips to Algeria between 1947 and 1949, where he learned Arabic and lived with Bedouin communities, inspiring works such as Arab and Camel from 1948.

Once back in Paris, he attempted a kind of landscape painting that would capture the spirit rather than the likeness of these extreme Saharan environments. As he explained in his catalogue text for Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1952, a paysage such as Chamelier was not intended to represent a specific site or an idealized place (although the title may point to one of the recent Algerian excursions) but to offer a journey into ‘the country of the formless’ – a landscape of thought.8 His intention was for these works ‘to show the immaterial world which dwells in the mind of man: disorder of images, of beginnings of images, of fading images, where they cross and mingle, in a turmoil, tatters borrowed from memories of the outside world, and facts purely cerebral and internal – visceral perhaps’.9

8 Jean Dubuffet, ‘Landscaped Tables, Landscapes of the Mind, Stones of Philosophy’ in Peter Selz, The Work of Jean Dubuffet, exh, cat, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (1962), p. 63. Dubuffet wrote this text in English with the help of the artist Marcel Duchamp for the eponymous exhibition catalogue at Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, 12 February – 1 March 1952.

9 Dubuffet, ‘Landscaped Tables’, p. 71.

“Ultimately, it’s about the universe that surrounds us, the places that confront us, all the objects that meet our gaze and occupy our thoughts.”

JEAN DUBUFFET, LETTER TO ANDREAS FRANZKE, 3 AUGUST 1980

76 SOTHEBY’S

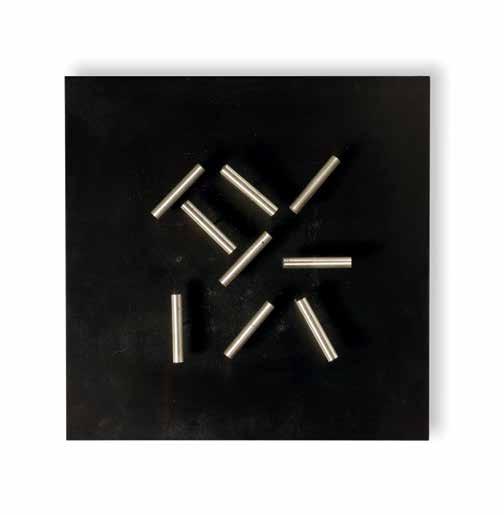

As time wore on, Dubuffet increasingly withdrew into this territory of philosophical enquiry. Why paint the world as seen in the mind’s eye when the mind’s eye could be an image in itself? His ‘L’Hourloupe’ works, for example, were began quite by accident when he was doodling while on the telephone in July 1962. The fluid figures he had absent-mindedly drawn with his four-colour ballpoint pen were then embellished with diagonal stripes and cut out and mounted onto black card – which became the beginning of a series that would possess him for more than 12 years, including paintings, sculptures, architectural environments and performances. Épisode from 22 January 1967, is characteristic, with its sinuous faces and shapes enmeshed in a patterned matrix – a reminder that we all belong to the same universal soup. The membrane between the so-called real world and the imaginary appears to be finer than we might have chosen to believe.

Playful and provocative to the very end, Dubuffet found new ways to conjure the vibrancy of our fragile existence. Finally abandoning his horizon line altogether, in his later decades he embraced a journey into the formless, much like Joana experiences in Near to the Wild Heart : ‘All of her body and soul lost their limits, mixed together, merged into a single chaos, soft and amorphous, slow and with vague movements like matter that was simply alive. It was the perfect renewal, creation’. 10

10 Lispector, Near to the Wild Heart p. 90.

Above Clarice Lispector, Near to the Wild Heart,1944

Left Exhibition poster for Jean Dubuffet: Retrospective Exhibition, 19431959 Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, in which Scène dans un paysage de rochers was featured

78 SOTHEBY’S

JEAN DUBUFFET

1901 - 1985

Scène dans un paysage de rochers, ou Trois malandrins dans les rochers

signed J. Dubuffet and dated 1946 (on the reverse); titled (on the stretcher)

oil, enamel, sand, and pebbles on canvas 21 ¼ by 25 ½ in. 53.9 by 64.8 cm. Executed in June 1946.

$ 1,200,000-1,800,000

PROVENANCE

Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York

Mr. and Mrs. Lee Ault, New York (acquired from the above in 1947)

Kende Galleries, Inc., New York

Acquired from the above in June 1951 by the present owner

EXHIBITED

New York, Pierre Matisse Gallery, J. Dubuffet: Paintings, 1947, no. 19

New York, Pierre Matisse Gallery, Jean Dubuffet: Retrospective Exhibition, 1945-1959 1959, no. 12, illustrated

New York, Museum of Modern Art; Art Institute of Chicago; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Work of Jean Dubuffet, 1962, no. 31

Ithaca, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, The David M. Solinger Collection: Masterworks of Twentieth Century Art, 2002-03, pp. 46, 49, illustrated

LITERATURE

Max Loreau, Catalogue des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, fascicule II: Mirobulus, Macadam et Cie (1945-1946), Lausanne, 1966, no. 150, p. 131; p. 100, illustrated

Gaëtan Picon, Le travail de Jean Dubuffet, Geneva, 1973, p. 48

5

80 SOTHEBY’S VISIT SOTHEBYS.COM/THEDAVIDMSOLINGERCOLLECTION 81