and follow instructions in equipment operator’s manuals

product

equipment routinely for problems that

accidents.

safety hazards and emergency procedures

approved rollover protective structures,

protective frames

that guards on

follow

South Dakota Farm & Ranch is an agricultural publication

informing SD and Midwest area farmers & ranchers about current topics and news.

publication fits the niche of our unique farmers and ranchers of the Midwest, and the diverseness we have in our area. Although the Missouri River divides our state, we are all South Dakotans and thank the land for supporting us each and every day.

readers may be livestock ranchers or row crop farmers, and everywhere in between, however, we all have a common goal in mind. We feed and support the growing population, and want the next generation to find that same love and support that agriculture can offer.

all South Dakota Farmers and Ranchers’ and when you advertise in South Dakota Farm & Ranch, you are immersing your company, product, and service into a growing community of dedicated farmers and ranchers. Welcome to South Dakota Farm & Ranch!

To subscribe to this FREE publication, contact South Dakota Farm & Ranch.

JONATHAN KNUTSON Plain Living

JONATHAN KNUTSON Plain Living

Growing up in upper Midwest agriculture taught me the certainty of two things: consistently inconsistent weather and regular disputes between the Farm Bureau and Farmers Union, the area’s two largest farm organizations.

Generalizing is always risky, but a few traits of the two groups almost always hold true. Farmers Union members tend to be Democrats with serious doubts about the free market and who consequently support a certain level of government involvement in markets worldwide. They also emphasize policies that they say promote small towns, rural schools, and smaller, more numerous farms owned and operated by families.

Farm Bureau members tend to be Republicans with serious doubts about government involvement in ag and who consequently support the free market. They’re not overly concerned with farm size, arguing that skilled, successful farmers should be free to enlarge their operations. They also say they support family farms, small towns and rural schools, but stress that the world has changed and ag must change with it.

Few Bureau and Union members join because they’ve thought carefully about it. They typically join because their parents and grandparents were members of that group. Membership, in most cases, is generational.

People outside ag may not realize how passionate members of the two groups can become about their respective beliefs. But consider all that’s involved: family identity, economic livelihood, way of life, and often Democratic vs. GOP political campaigns. The stakes are high, so differences inevitably take on greater import.

Sometimes feelings run too strong, with legitimate political and economic arguments boiling over into personal nastiness. No doubt some of the anecdotes are exaggerated. but there are many stories of Union and Bureau members deliberately snubbing each other at local stores or public events. At the very least, social contact between some members of the respective groups is limited, even though they have much in common as individuals, families and farmers.

Personal animosity has lessened over time, thank goodness. Most farm communities have lost so many farm families that the remaining farmers can’t be too choosy with whom they hang out. Bureau and Union members who once wanted nothing to do with each other have learned through newfound personal contact that (gasp!) members of the other group are human beings after all.

Disputes on the political level are somewhat muted today, too. Agriculture’s collective voice is often drowned out in our modern world, so members of the two groups usually stress publicly what they have in common, most notably support for federal safety-net programs.

By Erik Kaufman Mitchell Republic

By Erik Kaufman Mitchell Republic

MITCHELL — What started out as a promising 2022 growing season has had its expectations cut down significantly after rains failed to fall at the right times, producers say.

Work in the field is just getting underway, but early indicators suggest crop conditions and yields will be all over the map.

“Most guys have gone into one field or two to test it out, but they’re finding it’s all across the board,” said David Klingberg, executive director for the Davison County and Hanson County USDA Farm Services Agency offices. “They’ve seen some pretty dry corn, and the same with soybeans. It was just a race for which crop is going to get dry enough first, and then both got dry and now some is even too dry.”

Despite some relief from prevailing drought conditions in the forms of summer rains this season, overall rainfall has been down over the summer. Weather patterns resulted in spotty precipitation, with heavy rains falling on occasion over some fields and rarely over others.

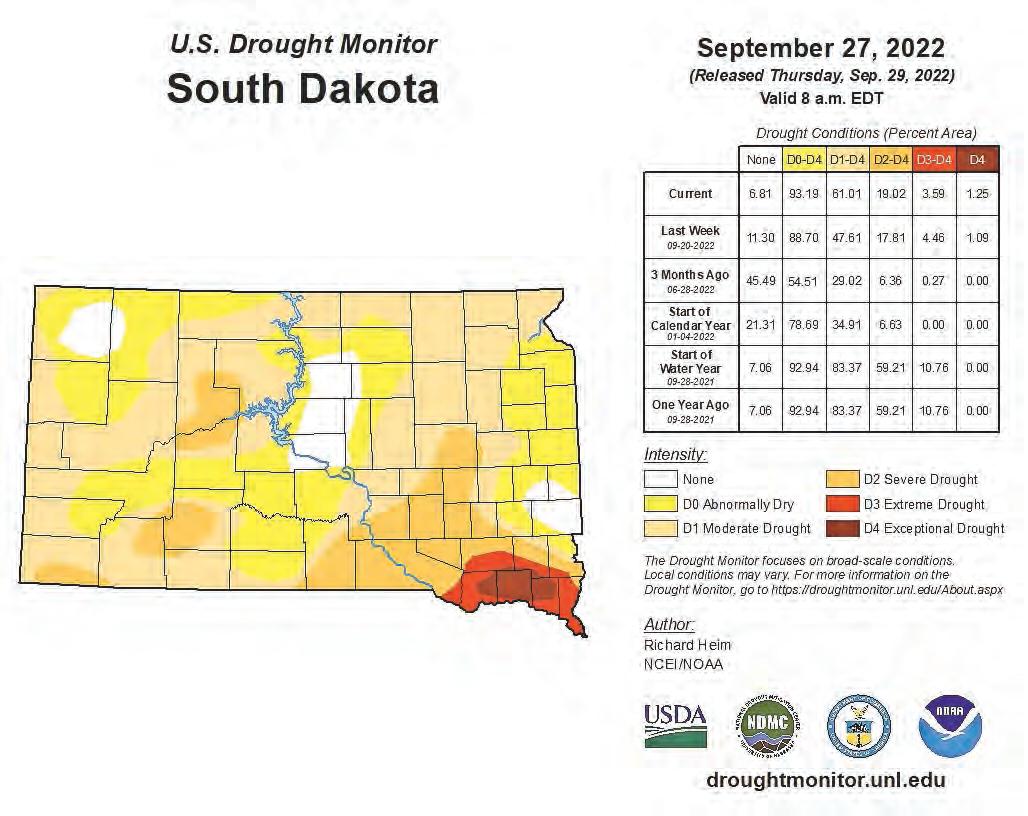

Overall, enough rain fell to reduce the drought impact on the state overall, with 21.31% of the state now experiencing no drought conditions, compared with only 7.06% at the start of the 2022 calendar year. But the summer rains hit early and then eased off. Areas experiencing no drought in the state climbed as high as 45.49% as recently as three months ago, before falling again, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

After that, the rains were much less consistent, and it’s showing its effect on what is coming out of the field now, which varies widely depending on location, Klingberg said. Corn yields in the area

are ranging from single digits to as high as 200 in some places.

“I’ve talked to a few guys, and some on the southern end (of Davison and Hanson counties) have already had their adjuster out there and have appraised it at 5 bushels per acre, so pretty poor. It’s not worth their fuel to harvest it,” Klingberg said. “In the middle it looks better and better, and getting on north it looks pretty good. Some guys are saying they might be able to make 200 bushels over the year. Just because they caught those timely rains.”

That appears to be true across a good portion of the region, with rains hitting or missing during the prime growing portion of the season.

“It seems like some people are in the exact right spot to catch every rain that comes through, and some people can’t catch a sprinkle to save their life,” Klingberg said.

House built indoors by Custom Touch Homes to maintain the highest quality and remove any weather elements and delays. Volume purchases of material and no labor delays allow us to pass SAVINGS on to you! Once the house is complete, it’s delivered to your site where we can add the finishing touches or you can line it up yourself.

homes

plant

Some of those who have gotten into the field to

soybeans have reported yields in the area of 50 to 55 bushels per acre, but Klingberg said that was still an early sample size and not necessarily

of overall soybean conditions.

As with any year, the amount of precipitation often dictates how the growing season will go. Farmers were a little more optimistic about the season going into it, Klingberg said, but the needed rains never fully developed around the state.

“Most guys were pretty positive when they started the year. We had some moisture, good but not great, but we were doing OK. Then early on there was a dry spell when guys were starting to plan and think it might be a tough year,” Klingberg said. “And then we caught rains countywide, and then it backed off into early summer. Had it continued on it would have looked great. But the spigot turned off.”

The weekly crop report for the USDA released Oct. 3 noted that topsoil moisture supplies were rated at 37% very short, 43% short, 18% adequate and 2% surplus. Subsoil moisture was similar, measuring at 30% very short, 49% short, 19% adequate and 2% surplus.

In terms of crop condition, South Dakota corn was reported as 10% very poor, 21% poor, 31% fair, 34% good and 4% excellent. For soybeans, the numbers came in at 8% very poor, 19% poor, 36% fair, 36% good and 1% excellent.

While farmers may have gotten a bit of a late start compared to last year, they are apparently ahead of the 5-year average, with 9% of corn harvested at this time last year compared to 8% this year and 5% being the 2017-2021 average.

Drought conditions in South Dakota have eased off in the past year, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

For soybeans, 9% is out of the field in 2022 compared to 15% last year and 11% for the 20172021 average.

Klingberg said planting conditions allowed many farmers to plant fencerow to fencerow, which added to the early optimism for the season, but yields may fall short because of the precipitation.

“(Current conditions) don’t make for great combining, but they’re not having to fight

the mud. Most were able to plant fencerow to fencerow, which is why it was so positive at the beginning,” Klingberg said. “But what comes out of that yield could be little.”

Dan Graber, who farms with his brother and father near Freeman, said with the dry conditions most of the summer, he considered himself lucky with the results they had seen so far in the field.

“We took out some corn and had a 115 bushel per acre average, and I don’t know where the hell

it came from. It never rained,” Graber said. “It was surprising. We were hoping for 70.”

He said they had only gotten through about 100 acres of soybeans and had seen roughly 28 to 30 bushels per acre, which he also considered better than expected due to the conditions. He guessed that wouldn’t be far off what other producers in the area would see, as well.

He said one fact that may have helped their results this year was a recent switch to no-till practices.

“I do attribute that to getting an extra 20 to 30 bushels (on corn). We have gone completely no-till and adopted those practices, as well as

using some cover crop, so none of our fields were blowing like they were last year,” Graber said. “Some guys would lose as much as a half inch of subsoil moisture with all the fields blowing.”

Even with the benefits of no-till, he figured they were seeing lower corn yield numbers than in 2021. They pulled in around 135 to 140 bushels per acre last year, and he credited that to timely rains that fell when the crops needed it.

Cathy Eichacker, who farms with her husband Steve near Salem, said they got underway with harvest about two weeks ago, and she’s expecting results to be below what they were hoping for at the beginning of the season.

“Our crop is probably going to be about half of what it should be. The grain cart driver and the semi driver have a lot of down time,” Eichacker said. “We’ve had kind of a double

was seeing in the field, but she knew it would be disappointing compared to expectations.

“I don’t want to even ask the boys,” Eichacker said with a chuckle.

Klingberg said some producers were a little short on hay and may be looking to purchase some or use corn stalks when needed, but Graber and Eichacker, both of whose operations include cattle, said they were sitting in relatively good shape. Eichacker said they had gotten three cuttings of alfalfa and chopped enough silage, and Graber said they had gotten cuttings of ditch hay when they could to supplement themselves.

It may be too late to help this year’s crop, but Klingberg said some rains once work wraps up with harvest could go a long way to helping conditions in the spring by boosting the subsoil moisture.

“Most guys wouldn’t mind a rain - but not right now. It’s too late

sword here with all the storms.”

Farmers in her area have had more than their share of bad luck this season. In addition to unreliable rains, they endured a pair of derechos that stormed through the area. The winds that came with them were strong enough to damage corn bins and cause extensive damage in Salem itself, but it also wreaked havoc on their field crops.

“We’ve been lacking moisture, but getting hit by two derechos, with the first hitting us pretty hard. It was devastating for our area. We have several farms hit, and then that’s all we did all summer was rebuild and repair,” Eichacker said. “Then the second one went through with that wind, and we had quite a bit of hail in our area, so that pretty much took the top end of the yield.”

She said she wasn’t sure on what the exact yield numbers her crew

for this year, but they wouldn’t mind it for some subsoil moisture,” Klingberg said.

Eichacker said they figured to wrap up harvest a little earlier than normal, which will be good to catch up on other farm work, as well as make it possible to enjoy some autumn activities.

“I think the boys will be able to go pheasant hunting. It will be an early harvest, and then other things can get done on the farm,” Eichacker said.

Graber said they were about a quarter through their harvest work, and after a light rain predicted for his area coming up, he said it would be straight on to the end of the season.

“We’re going to get a little rain tomorrow, but after that I think everything will be ready. It will be pick a field and go,” Graber said.

Our crop is probably going to be about half of what it should be. The grain cart driver and the semi driver have a lot of down time.

ELLENDALE, N.D. — Rural America is currently facing an extreme shortage of veterinarians and is in desperate need of young veterinary professionals starting clinics in small, rural towns. Luckily for Ellendale, in south central North Dakota, Dr. Erin Christ did just that.

Christ has had a lifelong passion for animals and knew at a very early age that caring for them was something she wanted to do as a career.

“I had a dog when I was a kid that had a vaccine reaction after we got his vaccinations, and I just wanted to help him and I didn’t know how to. So it all just kind of fell into place,” she said. “I was also the kid that was saving the sick kittens and worried about all the little animals.”

After graduating high school, Christ attended North Dakota State University for her undergraduate degree. Following graduation from NDSU, she went to veterinary school at Iowa State University. She then worked at a veterinary clinic in Wetonka, South Dakota, for four years after becoming a veterinarian.

Christ said her time there was imperative to learning the trade; however she faced some obstacles along the way. Christ was one of two veterinarians at the clinic, her co-worker being male. She found that many producers would not allow her to work on their livestock and would insist on waiting for her male counterpart to become available.

“There were certain clients that only wanted him,” Christ said. “Sometimes the community isn’t as

receptive to get new young vets in there, especially women, and right now the majority of the vets coming out of vet school are women. Some are very good and they understand that that’s what you’re going to get, but there still are some that are going to push back at you.”

Despite getting pushback, Christ persisted and decided to take the next step in her career: opening up her own clinic. A building came up for sale in Ellendale, North Dakota, and Christ knew this was the opportunity she was looking for. She opened Country Roads Veterinary Clinic in July 2021 where she treats large animals, small animals and anything in between. While she prefers working with livestock, she believes the smaller animals help fill the gaps. She also jokes that during the winter months, it’s nice to be able to stay out of the cold barnyard and in the warm office walls.

Oftentimes Christ is pulled in two opposite directions when disaster strikes on the farm.

“There’d be times where you’d get phone calls in two different directions at the same time and you just got to choose where to go first,” she said. “It definitely cuts into the second guy trying to get a live calf out of it.”

In an effort to avoid those emergency citations, Christ teaches her clients what to do in certain emergency situations. She hopes this will lessen the frequency of emergency situations on the farm where her assistance is needed,

difference between a calf living and dying,” she said.

Christ is not originally from Ellendale but does have family that live in the area. She said being a part

By Emily Beal AgweekLEFT: Dr. Erin Christ tends to both large and small animals at her clinic. She tries to teach her clients what to do in certain emergency situations on the farm.

BOTTOM: The sign for Dr. Erin Christ’s own vet clinic, Country

fellow, young veterinarians that are just starting out to do the same.

“Be a part of your community. It helps when they all know you,” she said.

Allegiant Seed from CHS brings you the most advanced genetic technologies. With local plot data, we have the traits that are proven to perform right in your backyard. Ask your CHS Farmers Alliance Agronomist about the right seed for your farm.

see the cooperative difference.

Cleaner cutting with enhanced cutterbar features including increased knife overlap and thinner overall profile.

Improved swath control for both wide swaths and narrow windrows, a new swath gate and doors provide better crop control and increase adjustability.

Outstanding contour following, up and back header geometry helps to maintain a more consistent knife height delivering cleanly cut stubble.

Cuts clean and saves time, the QuickMax knife system is standard equipment.

All models are equipped with the MowMax II PLUS Large Disc, true modular disc cutterbar backed by the MowMax 3-Year extended cutterbar warranty.

Young pigs inside one of the barns that the Quandt family operates near Oakes, North Dakota. The Quandts don’t own the pigs but have a working relationship with an “integrator” that owns and markets the pigs and pays the Quandts for barn space and labor

By Jeff Beach AgweekAdvocates for animal agriculture in North Dakota hail Justin Quandt and the modern hog barns his family built near Oakes as an example of what is possible in the state.

The Quandts don’t own the hogs in their barns; they are owned by an “integrator” in South Dakota that pays the Quandts to house the pigs and provide the labor until the pigs are market weight. The integrator provides the feed — sometimes buying corn from the Quandts — and decides when to pick up pigs for market.

“Our duties are to keep the barn heated, cooled in the summer, pay the electricity bills, look for the sick ones to take care of, take care of the animal health, and then order the feed when we need more feed, and then he pays us the rent per pig space,” Quandt said.

But for more North Dakota farmers to take advantage of the opportunities that animal ag

presents, Quandt says the industry needs to overcome the “stigma” associated with large scale hog barns and instead see the value in diversifying and using manure to promote soil health and save on fertilizer costs.

Quandt, who also raises cattle and farms with brothers and uncles near the South Dakota state line, gives a lot of credit to Amber Boeshans, the executive director of the North Dakota Livestock Alliance, with helping to navigate the process of getting the financing and permits needed to make the two 4,800 head barns possible.

Boeshans gives this assessment of animal agriculture in North Dakota:

“We’re about where South Dakota was 15 years ago.”

South Dakota has double the number of beef cattle that North Dakota has, and North Dakota has dropped out of the top 10 beef producing states, though some of that may be related to the 2021 drought that withered pastures in the state.

North Dakota is far behind South Dakota in the

number of hogs and dairy cattle in the state.

South Dakota has more than 2 million hogs while North Dakota has just 148,000, according to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. North Dakota has just 15,000 milk cows while South Dakota has 170,000.

The North Dakota Livestock Alliance started in 2017 and promotes “responsibly growing all types of animal ag across the state,” Boeshans said as the group on Sept. 28 held an event in Fargo to promote raising pigs in the state.

But that growth has been slow to come and ag leaders in the state point to a variety of factors:

► Anti-corporate farming laws.

► Lack of livestock and dairy processing.

► Prohibitive local ordinances.

► Misconceptions about animal ag.

In an interview with Agweek at the 2022 Big Iron farm show at West Fargo, North Dakota

Gov. Doug Burgum said neighboring states are “clobbering us” because of North Dakota’s anticorporate farming law.

Burgum said it’s obvious that it’s “not aptitude.” Instead, “it has to be red tape and regulation.”

But Burgum said creating a modern, efficient livestock operation requires significant capital and North Dakota’s anti-corporate farming law, now 90 years old, make that nearly impossible.

The North Dakota Livestock Alliance doesn’t take a stand on that law and other ag policy.

“We will follow the laws of the state,” Boeshans said.

But she adds: “Have I had projects not be able to function in North Dakota because of that law? Yes.

“And it’s not just pigs; it’s been extremely hard on dairy.”

“It is a limit, there’s no doubt about that,” said Craig Jarolimek, a Forest River, North Dakota, hog producer. “However, there are ways to get around that,” he said, by creating some partnerships to bring in some outside capital.

Boeshans the capital required, often millions of dollars, means “sticker shock” that must be overcome.

North Dakota has been reluctant to change its 90-year-old ban on corporate farming, though it has been expanded to allow cousins to work together as a part of a partnership.

In 2015, North Dakota legislators passed a bill that would have exempted hog and dairy farms from the law. Farmers Union led a referral effort that led to 76% of voters voting to reject the exemptions.

“It’s going to take the citizens of North Dakota” to change it, Burgum said.

South Dakota had a similar law, known as “Amendment E,” until 2003, when the case South Dakota Farm Bureau Inc. v. Hazeltine led to it being struck down.

What some feared would be a corporate takeover of South Dakota ag hasn’t happened, said Bob Thaler, South Dakota State University Extension swine specialist.

He sees the change and growth of animal agriculture as providing opportunities for the next generation of farmers.

“There’s a lot of family farms that contract feed for Smithfield,” Thaler said, referring to Smithfield Foods, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, one of the large pork processors in the region.

“This is allowing that 20-something to come back to that farm or ranch,” Thaler added.

Mark Watne, president of the North Dakota Farmers Union, stands by the corporate farming law.

ANIMAL: Page 14

He points to the furor over a trust connected to Microsoft founder Bill Gates buying land in northeast North Dakota.

“Everybody’s mad because Bill Gates bought land,” Watne said. “They think changing this corporate farming law is going to make that any better? It’s just going to increase that thing that everybody’s upset about.”

Watne said what is really needed is livestock processing in the state.

He says, yes, South Dakota does have looser corporate farming laws, but it’s been that state’s willingness to try to attract businesses like cheese processing that have built that state’s dairy industry back up.

“South Dakota developed cheese first, as a commitment to provide processing for the milk into cheese in South Dakota. They needed more cows, so the cows came,” Watne said. “We let our dairy processing plants die away.”

When searching for a company to partner with, Quandt said he was told that their farm on the southern edge of North Dakota was too far from the Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls.

“I priced out other companies, and all of them told me you’re kind of out of our range for trucking the pigs down to the processing plant,” Quandt said.

Boeshans said she would love to see more dairy processing, and some dairy and livestock producers are taking the initiative.

“There are a lot of livestock producers that are putting up their own smaller processing plants,” Boeshans said.

Watne said the state needs to help more.

“There’s this constant, constant competition to attract business,” Watne said. “So the state needs to step up and attract the processors.”

Randy Melvin wants to add animal ag to his farm about 35 miles west of Fargo, in part, he says, to provide an opportunity for his children to be involved in the farm.

But he was thwarted by ordinances in Howes Township in Cass County that made siting a hog barn impossible.

The North Dakota Farm Bureau took up Melvin’s

cause, taking the township to court. On July 30, 2022, North Dakota East Central District Judge Wade Webb ruled that many of the township’s requirements, such as setbacks, were unlawful.

“The Township does not have authority to regulate an animal feeding operation’s appearance, burden on streets, nor general compliance with the Township’s Comprehensive Plan,” Webb’s ruling said.

Tyler Leverington is the attorney with Ohnstad Twitchell law firm in Fargo who is handling that case and a couple of other similar cases in Ramsey County, near Devils Lakes, North Dakota.

He said many townships “got sold a bundle of ordinances, once upon a time.”

“I’m not just talking animal feeding operation ordinances — they got a whole packet of ordinances when they bought these things from some of these engineering firms,” Leverington said.

The ordinances haven’t changed because they haven’t been challenged, he said.

“But when you have townships that either are adversarial to, whether it be certain individuals, or animal agriculture more generally, it just can create a huge mess because the permitting surrounding developing animal agriculture is an expensive time-consuming process,” Leverington said. “I think, over time, that’s been a huge impediment.”

Leverington also works in Minnesota.

“If you asked most North Dakotans, ‘Who has more red tape and overzealous regulation, North Dakota or Minnesota?’ They would just laugh and say, ‘Of course Minnesota does.’ But the reality is, when it comes to animal agriculture, it is much more difficult to locate an animal feeding operation in North Dakota than it is in Minnesota,” Leverington said.

Leverington said farmers understand that rules and standards need to be in place, but can’t be onerous.

“People should remember that the regulations at the township level are above and beyond a very extensive permitting process at the state level,” Leverington said.

Quandt said their application with the North Dakota Department of Environmental Quality was 188 pages long for their two barns. Those barns are in neighboring townships, one of them with only a handful of residents.

Quandt said there was some concern about truck traffic from a resident of one township but otherwise there was not much of an issue.

One of the missions of the North Dakota Livestock Alliance is to meet with county and township officials to help answer questions about modern animal ag and try to get ahead of those concerns.

The Alliance was not in existence when Randy Melvin made his attempt to bring a hog facility to Howes Township in 2015. And he hasn’t given up.

“Before the day I die, I want to have animal ag on our farm,” Melvin said.

Dealing with rules and regulations may be easier than changing people’s attitudes about large scale animal ag — the “stigma around it,” as Quandt says.

He has tried to be transparent about his hog operation. For biosecurity reasons, visitors are not allowed inside the barns, but he had an open house in the barns before the pigs arrived, and a virtual tour is on the North Dakota Livestock Alliance website.

His point is that a modern hog facility and manure handling system does not have the odor that some people associate with animal ag.

Standing outside one of his barns, “Yeah, you know they’re there, but it’s not burning your nostrils or anything,” Quandt said.

For Quandt, the manure that gathers in the pit of his hog barns is piped to nearby cornfields and diluted and sprayed through the irrigation system. “So there’s no honey wagons dragging, spilling manure around. It’s all self-contained.”

And by his math, the number of trucks that come in and out of their barns, which are double the size of a typical hog barn, is the same number of trips required to make a corn crop on one quarter of irrigated land.

The worries about odor and traffic, “a lot of those reactions are plain not understanding,” Jarolimek said.

There can be a lot of misinformation spread about livestock operations, he said.

Thaler said North Dakotans can look south for how livestock can improve the employment base and quality of life in rural areas.

“We don’t have rivers of manure running down the ditches,” Thaler said. “We don’t have these plumes of odor that are killing people.”

Advances in barn construction and manure handling have made livestock operations into better neighbors.

“You drive past it, and you’re not even going to know they’re there.”

for a feature story, I step back from a question that makes him or her uncomfortable, and pursue it later after he or she has become more confident talking to me. If they still decline to comment, I move on because I respect the person’s decision to not share that information.

As a private, introverted person by nature and a journalist by profession, earlier in my journalistic career, my personality and my job responsibilities were at odds with one another.

On one hand, I understood the desire by sources to withhold details about their lives and professions that they weren’t comfortable with sharing with tens of thousands of readers.

But on the flip side, I knew that it was my responsibility as a reporter to ask the “hard” questions, even if the sources I wanted to interview didn’t want to answer them.

After nearly 40 years reporting the news — much of that time, agricultural news — I am comfortable interviewing people regardless of the questions I have to ask them. Experience has taught me that the worst thing that can happen when I ask a question is that the interviewee won’t answer it.

I also have discerned over the years when to press people to be more forthcoming. If the person is a private citizen I am interviewing

Meanwhile, if the source is someone I’m interviewing for a story about agricultural policy or some other “hard news,” I’ll press them for the answer because I believe it’s pertinent to the story. If they still refuse, then I will stop asking because it’s their right as private citizens to do that.

When I interview farmers or ranchers, for example, who decline to tell me the number of acres they farm or the number of cattle in their herds, I don’t press them for an answer if I’m writing a feature story about their operations. If I’m writing a news story about how government policy affects them, I’ll explain to them that sharing with me details about their operations is pertinent because the information illustrates how the policy affects the people impacted by it. But if the sources still don’t want to answer after I give them that explanation, while I may not like their decision, I respect it.

However — and it’s a big “however” — when I interview sources who are public servants about projects they have championed or who is supporting projects that benefit from taxpayers’ money, I don’t take “no” for an answer

without pursuing the question by asking it in several different ways and reminding the source that the public has a right to know what their response is.

If they still won’t answer, I include that in my story so readers know that Agweek has done its due diligence reporting the story, but the sources are dodging the questions.

Over the years, most of the time, representatives of agricultural companies, including many in the private sector, have been forthcoming with their answers to tough questions I’ve asked because they know that the people in their communities not only are interested in their successes and failures, but also are impacted by them. They understand that answering the questions is an important part of maintaining their credibility and the trust of community members.

That’s why the resistance I’ve run into during the past year when I’ve been reporting on a couple of new agricultural manufacturing companies — one of them still working to get off of the ground and the other experiencing numerous problems during start-up — has evoked considerable head-shaking from my end. Both companies were touted by the city’s economic developers and by city officials, and community members have a stake in their success or failure.

From the local government officials involved in the projects to the leaders of the companies, though, I’ve hit numerous brick walls while

reporting. Many of the individuals involved with the projects have not been forthcoming with information, including phone numbers and emails for the company leadership, have not responded to emails that asked questions, and have refused to answer questions when I finally did reach someone.

Meanwhile, public officials involved in the projects repeatedly have pointed out, at public meetings, the success of existing agricultural companies in the community as examples of how important the new ones will be to the area economy and the marketing opportunities they will offer to farmers.

It apparently doesn’t occur to the public officials that part of those companies’ successes has resulted from gaining the trust of the community through being transparent about the way they do business, responding to the concerns of the public and being available to the media to answer questions, even if they would rather not do so.

As an agricultural reporter, my job is to report the news and not weigh in on whether a project or company should or should not exist. The questions I ask are not a judgment for or against them. I believe that providing forthright answers that I and other members of the media can report is their duty. The people have a right to know.

Ann Bailey lives on a farmstead near Larimore, N.D., that has been in her family since 1911. You can reach her at 218-779-8093 or abailey@agweek.com.

Halloween takes place during a time of year characterized by earthen-colored chrysanthemums, leaf-lined walkways and crisp autumn air. As colorful as the costumes children wear for trick-or-treating may be, nature’s beauty is unsurpassed this time of year, and the scores of pumpkins, gourds and squashes on display only add to that colorful melange.

The Cucurbitaceae family may be best known for pumpkins, squash and gourds, but there actually are 800 species that belong to this family. While they share many of the same properties, these fruits each have their own unique attributes.

The main differences between squashes, gourds and pumpkins is their intended purposes — whether they’re ornamental or edible.

Squashes come in summer and winter varieties. Winter ones do not actually grow in the winter; in fact, they’re harvested in late summer and early fall, but the name references the hard shell casing that protects the tender pulp inside. Zucchini are summer squash because their outer flesh is tender,

while butternut, acorn, spaghetti, and hubbard squashes are winter squashes because they feature a tough skin. Even though it takes some effort to crack that shell, the dense, nutrientrich flesh inside is well worth the workout.

Gourds are essentially ornamental squashes; they aren’t cultivated for eating. Instead they are bred to look beautiful and unique in autumn centerpieces. Types of gourds include autumn wing gourd, warted gourds, turban gourds, and bottle gourds. Each gourd is unique in its shape and color.

Pumpkins come in ornamental and edible varieties. Even though all pumpkins can be consumed, some taste better than others. Small pumpkins tend to be decorative because, according to Nutritious Life, they do not have enough meat inside to make them worthy of cooking. However, sugar pumpkins are best for baking and cooking favorite recipes, states the resource Pumpkin Nook.

The festive hues and flavors of squashes, gourds and pumpkins are one more thing that makes Halloween and autumn special.

Pragmatic flexibility has developed over time. Union members may distrust the free market, but they’ll take the strong profits that the free market sometimes provides. Bureau members may dislike government involvement, but they’ll take safetynet payments when the free market fails to cooperate.

As a journalist, I’ve walked the fields and sat at the kitchen tables of both Bureau and Union members. I’ve found that neither group’s membership has a monopoly on good farmers or good human beings. I’ve also found that each group has a few rascals, too. (All groups do, of course.)

Curious where I stand? Well, a

news-media-hating caller once denounced me as a “blanketyblank big-city liberal because all you blankety-blank journalists are blankety-blank big-city liberals.”

But regular readers of this column — very small in number but with abundant, much-appreciated loyalty — know I’m a small-town guy who believes less government is usually better government. That makes me a stronger, though imperfect, fit in the Farm Bureau school of thought.

But what matters is that both the Farmers Union and Farm Bureau advocate policies they sincerely believe are best for American ag. Their disputes aside, neither group has a monopoly on good ideas. All of us in ag would do well to remember that.

Jonathan Knutson is a former Agweek reporter. He grew up on a farm and spent his career covering agriculture. He can be reached at packerfanknutson@gmail.com.

A panel of farm group leaders talked about the future of farm policy at Minnesota Farmfest on Aug. 3, 2021. Farmers Union and Farm Bureau, the two biggest farm groups, tend to attract different philosophies, but most farmers now recognize the commonalities between the groups.

Choose AlignpoweredbySanford Health Plan foranall-in-one Medicare Advantageoptionwith plansfromalocal insuranceprovider youcan trust.With Medicare PartsA and B, prescription coverage and extrabenefits, onecomplete plan caresfor thewhole you.

AlignpoweredbySanford HealthPlanis

AlignpoweredbySanford Health Plan dependson contract

notdiscriminate on thebasisofrace, color, national

thelaw.Thisinformationis nota complete list of

ferent format

serviciosgratuitos

vicesorinformation