Southeast OHIO

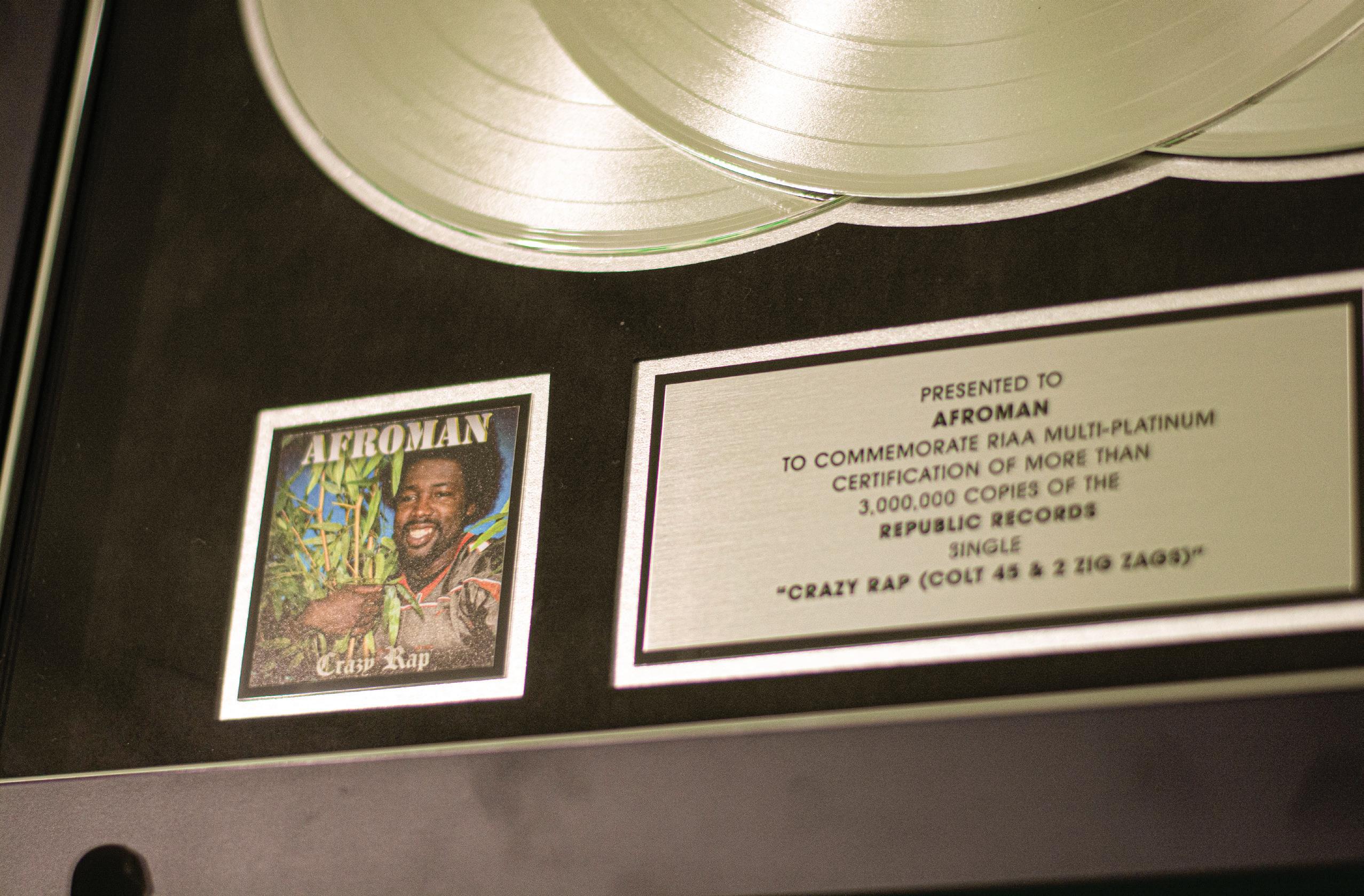

Afroman in the house!

Adams County’s artist extraordinaire shares his story of success

SEO digs up the dirt on region’s rich agriculture industry

Talking

What do leather, pizza and pawpaws have in common? They’re all inside!

Adams County’s artist extraordinaire shares his story of success

SEO digs up the dirt on region’s rich agriculture industry

Talking

What do leather, pizza and pawpaws have in common? They’re all inside!

For nearly four years, the staffers behind Southeast Ohio’s 2024 summer/fall issue have learned, worked and lived in Athens. I know the region well, having grown up 40 minutes north, but just like my classmates from counties and states away, I was often moved this semester by the consistency of kindness, determination and humility exhibited by those who call Southeast Ohio home.

Many of us drew our first impressions of our story’s subject by studying the bridges of noses, expressions on cheekbones and creases etched into foreheads—attempting to tell the complete stories of those we only saw parts of. But in time, we realized the access to the real storytellers, the “windows of the soul,” are the eyes—the eyes of those who have stories to share.

During the last four months, Southeast Ohio writers and photographers have traveled throughout the region to capture your most telling facial features. In them, they’ve found a hunger for daredevil delectables in Vinton County (Page 9), a youthful resolve to reign victorious in Monroe County (Page 12), a calling to harness a curing current in Adams County (Page 16) and an itch to start a farm from scratch in Perry County (Page 24).

Joseph Foreman, known worldwide as Afroman, shares a story while standing outside his showplace garage in Adams County. Read the story on page 34.

MISSION STATEMENT

Southeast Ohio strives to spotlight the culture and community within our 21-county region. The student-run magazine aims to inform, entertain and inspire readers with stories that hit close to home.

We have only witnessed a fraction of the accomplishments of the people we’ve come to know as neighbors, but we would like to share their stories and experiences with you now. It is our greatest hope that you see what we see: the spirited souls of Southeast Ohio.

Happy reading,

-Addie Hedges Editor-In-Chief

-Addie Hedges Editor-In-Chief

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Addie Hedges

MANAGING EDITOR

Carmen Szukaitis

DEPUTY EDITORS

Ashley Beach

Tate Raub

COPY & RESEARCH EDITOR

Lillian Barry

THE SCENE & WHAT’S YOUR STORY

EDITOR

Morgan Podkul

BEHIND THE BITE EDITOR

Ryan Maxin

IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD EDITOR

Cole Patterson

TALKING POINTS EDITOR

Jamie Miller

WEBSITE EDITORS

Max Abbatiello

Juliana Colant

PHOTO & VIDEO EDITORS

Hannah Campbell

Jessica Stelzer

MULTIMEDIA & AUDIO EDITORS

Sedric Granger

Cade Williamson

SOCIAL MEDIA

Southeast Ohio Magazine

@SEOhioMagazine

@seohiomagazine

FIND US ONLINE

southeastohiomagazine.com

EDITORIAL OFFICE

Southeast Ohio Magazine

E.W. Scripps School of Journalism

1 Ohio University Athens, OH 45701-2979

WRITERS

Alex Ifft

Donovan Hunt

Arielle Lyons

Anna Millar

Trinity Trimble

Zach Vogeler

Zach Zimmerman

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Emma McAdams

FACULTY ADVISOR

Dr. Elizabeth Hendrickson

Perry County’s Cherokee Valley Bison Ranch needs no deer or antelope to feel like home.

As the average age of farmers continues to increase, the agricultural industry must adapt.

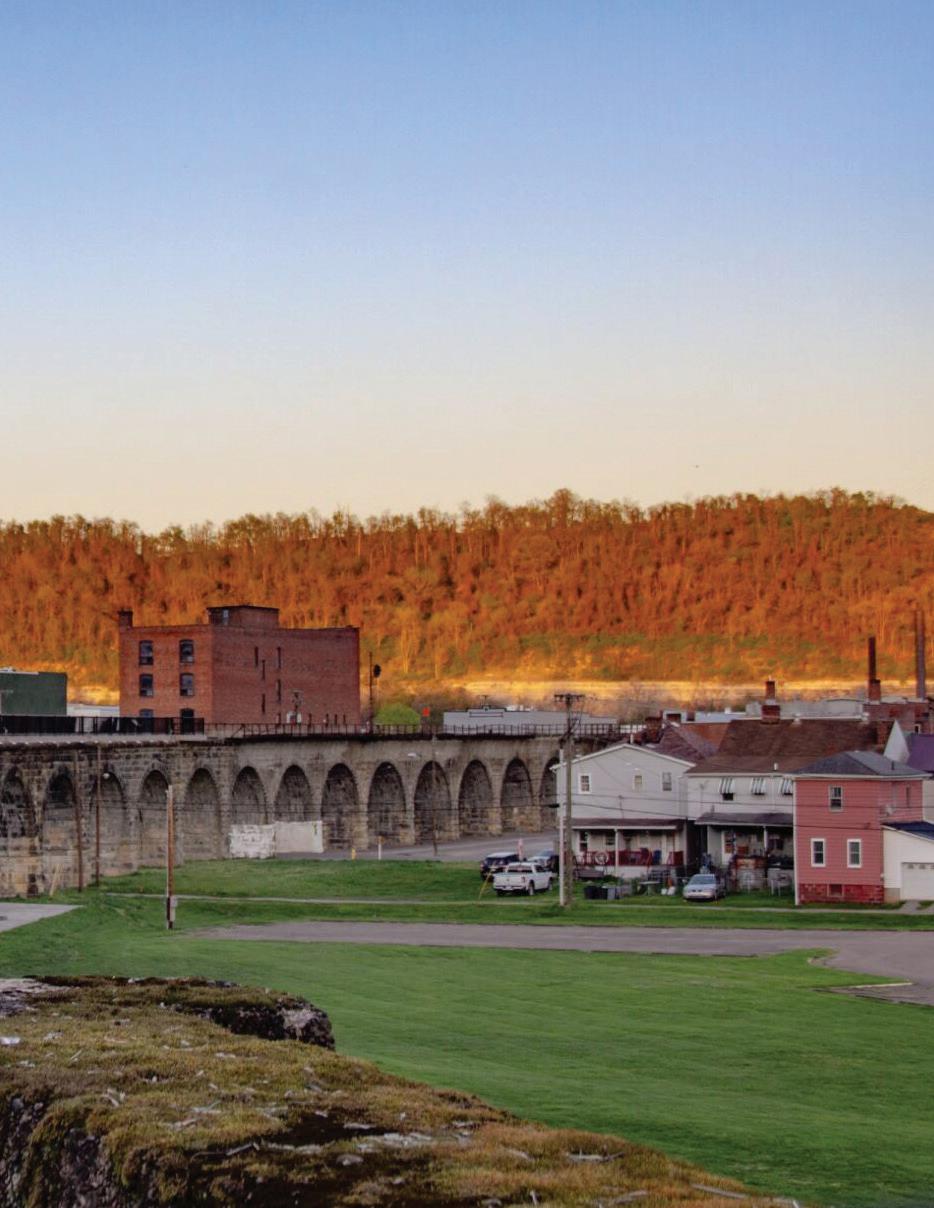

The Great Stone Viaduct is reimagined as a functional (and beautiful) public space

by Donovan Hunt

The Great Stone Viaduct has stood tall for over 150 years, connecting Bellaire, Ohio, to Benwood, West Virginia, over the Ohio River by rail.

Construction on the bridge began in 1870, five years after the Civil War, and each arch is supported by 37 ring stones representing the nation’s then 37 unified states. Dan Frizzi, trustee of the Great Stone Viaduct Historical Education Society and its original organizer, says every stone on the arch is supported by a central keystone and if one stone were to falter the bridge would collapse.

Originally part of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad system, parts of the track still carry trains. However, in 1996, a portion of the track ceased operations. Frizzi says it quickly fell into disrepair, which encouraged him to unify the community’s support by forming the Great Stone Viaduct Historical Education Society and purchase that portion of the track.

“When we first acquired the property, you couldn’t see but these first few arches,” Frizzi says. “There was so

much vegetation, brush, debris and overgrowth.”

The group, which became a 501c3 chartered nonprofit in 2012 — with the help of donations from the people of Bellaire and, later, grants from the Ohio Department of Transportation — has cleared vegetation, installed information markers, removed abandoned buildings, illuminated the pathway and paved a walkway that overlooks the former track. Following the numerous improvements, the Society constructed a plaza at the base of the bridge that showcases the efforts of its donors through numerous plaques.

The Society has dedicated itself to educating the local community and preserving and improving the historic bridge and the land it covers.

However, its goals are not yet fulfilled, as Frizzi says, the Society has plans to develop the rest of the five acres purchased to further benefit Bellaire.

“An author writes a book because he wants people to read it,” Frizzi says. “And the inspiration for this, the people actually using it, it’s really gratifying.”

The Great Stone Viaduct’s newly installed paved walking path overlooks the former track. Fun fact: the metal southbound portion of the bridge (not pictured) was featured in the 2010 Denzel Washington movie, Unstoppable.

The flavor of the pawpaw sells itself,” says Chris Chmiel of Integration Acres farm in Albany. An overcast afternoon in the orchard illuminated the farmer’s pawpaw trees and shrubs in winter blue sunlight. Small buds decorated trees, alongside pink, white and green ribbons. The plants were treated to an unusually warm day in February.

Chmiel smiles when speaking about his produce. One of the cofounders of the original 1999 Pawpaw Festival, the farmer is passionate about spreading admiration for the fruit far and wide.

Commonly compared to the taste profile of a banana, mango or pineapple, the American pawpaw is native to the eastern U.S. and southern Ontario, Canada. Designed to endure fertile valleys and hills, pawpaw trees are well-suited for the gentle foothills of Appalachia.

In Southeast Ohio, the fruit has a history as rich as the soil in which it grows. It was once called riwahárikstikuc by the Pawnee and tózhaⁿ hu by the Kansa. Now, to Chmiel and many Southeast Ohio residents, the pawpaw is a coveted crop.

Although a champion of the native fruit, Chmiel understands a farm can’t stay in business selling pawpaws alone. In addition to pawpaw products, Integration Acres sells Spicewood allspice and jam, ramp crackers, hickory nuts and shelled black walnuts.

Chmiel says Integration Acres’ website is one of its main source of revenue. The website offers sapling cuttings, raw pawpaws and pulp, among other products. Chmiel says most sales are shipped out-of-region.

Still, he notes the benefits of also reaching the local buyer. "If you're selling at a local farmer's market, the money made at the market selling is part of making ends meet, but another very valuable part of the market experience is the community relationships that are established," Chmiel says, referring to the profitability of farming in the modern age.

Southeast Ohio resident and gardener Shelley Beard supports a model of food distribution that prioritizes affordability, locality and community. Beard gives away her eggs to neighbors, friends and family, a tradition passed down from her family’s habit of gifting produce.

“[My uncle and aunt] shared all sorts of crops: strawberries, corn, apples, eggs. There was plenty to go around,” Beard says. She, like Chmiel, promotes increased accessibility to local foods, be it eggs or pawpaws.

Beard also considers the necessity of affordable food when she shares her goods. “For me, it’s about having security. I grew up facing food instability in Appalachia.”

“There is such inequity,” Beard says. Though she was born in Appalachia, Beard moved to a wealthy suburb on the outskirts of Columbus in the ninth grade. She says this

If you’re selling at a local farmer’s market, the money made at the market selling is part of making ends meet, but another very valuable part of the market experience is the community relationships that are established.

–ChrisChmiel

of Integration Acres.

is when she began to be disgusted with food inequity. “Nobody seemed to worry about the things we did,” Beard says. “Nobody seemed to be thinking about food.”

Today, Beard maintains a garden and a coop full of chickens to ensure a baseline of food stability and ethical acquisition of food. She speaks fondly about each of her six poultry children.

“I put a space heater [in the chickens’ pen] when the weather got cold. But I know exactly what my chickens are eating. I know they’ve lived a happy and comfortable life,” Beard says. The chickens feast upon frozen blueberries in the summertime, and Beard’s son has even immortalized them with artwork in her kitchen.

Beard adds that she buys products like dairy and meat from the local farmer’s market. Because of the proximity of farm-to-market, there is also an assurance in minimized fossil fuel emissions. This contrasts with large-scale farming production and transportation, which are leading causes of fossil fuel emissions, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Both Beard and Dr. Art Trese of Ohio University’s Plant Biology Department say they have familiarized themselves with local and large-scale food production so residents of the community in which they live can ensure their pawpaws, eggs and other available goods are ethically and locally sourced.

Trese says he shops at farmers markets and local grocers because it allows him to endorse the farmers he knows.

“I buy my meat from Seamen’s because I know some of the farmers who sell there. I’ve been to their farms,” Trese says. “I buy from the farmer’s market to help people out.”

Family is the secret sauce at Lloyd’s Pizzeria, a Waverly mainstay since 2007

by Juliana Colant photography from Lloyd’s Pizzeria’s Facebook PageOpening the door to Lloyd’s Pizzeria feels like stepping into a family member’s living room. It’s laid back, with a counter for ordering food and drinks and tables and booths for dining in. Along one wall is a row of arcade games including old-school favorites like Centipede and Ms. PacMan.

Lloyd’s finds its home in Waverly, which has a population of more than 4,100 people, according to the latest U.S. Census figures. Although there are about eight pizza shops in town to choose from, in a world crowded with restaurant chains and franchises, Lloyd’s is one of a kind.

Lloyd’s opened in 2007, and Michelle Scott has been with the business since the beginning. In 2019, she became the owner, taking over for her boss, Lloyd Harmon, the pizzeria’s namesake. “He kind of treated me like a daughter,” Scott says.

She attributes his legacy to what makes the shop so special. “Everybody you know, knows Lloyd,” Scott says.

Lloyd’s customer connection

Today, Scott is also a family face in town. Scott says connecting with customers and Lloyd’s many regulars is an integral part of the pizzeria’s business model as well.

“Most of them are just the best people in the world,” Scott says. “They see me in the store and I’m like, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’”

Conversing with people she doesn’t know well didn’t always come easily for Scott, but that has changed since she became owner. “To be able to come have conversations with people I really don’t know that well ... it kind of broke me out of that,” Scott says.

Shyann May classifies her role at Lloyd’s as “a little bit of everything,”

working in crew, delivery and as a manager since 2016. She cites a recent interaction with a repeat customer who represents the pizzeria’s connections with its customers.

“She loves for us to sit down with her, her and her husband, and we join them to eat and they share their food with us,” says May. “It’s so cute, and they tell us their little stories. It’s just precious.”

Eight employees make up Lloyd’s team. Two of the employees are Scott’s children, and the rest are various family members or members who feel like family. To May, that environment is what makes working at Lloyd’s rewarding.

“The employees are just amazing, and it’s like your own little family,” May says. “You just create a bond with everybody.”

In addition to running the business, Scott is busy raising her 13-year-old son.

“My kids all work here, and my 13-year-old, he’s going to end up here, probably, if everything works out, and he’s excited for it,” says Scott. “And my grandkids are even ... like, ‘I’m going to work there.’”

Her 4-year-old grandchild will often visit the restaurant and excitedly sit in the drive-thru window, waving and chatting with customers.

The combination of savory food and relaxed atmosphere, draw in new customers and keep regulars coming back.

Cody Perkins has lived 10 minutes from Waverly his entire life, meaning

he’s taste-tested the many pizzarias. “You just walk away feeling satisfied,” Perkins says. “Not only is the food good, but it’s also like good customer service and everything.”

10 a.m. - 7 p.m.

The Vinton County Air Show at the Vinton County Airport is one of the most popular and successful events of its kind in Ohio. It dates back to the 1970s and attracts around 5,000 to 6,000 attendees annually. During the one-day event, cars crowd the grassy parking lot, lawn chairs dot the viewing area and planes soar high above.

But what draws some people to the air show isn’t the dramatic aerial stunts or the eardrum-pounding whir of the planes’ engines, it’s the chicken.

As awe-inspiring as the air show may be, jaws really drop at the sight of the show’s signature meal, which includes half a chicken, potato salad, baked beans and a roll for $13.

Andy Adelmann has been cooking the famous chicken since the air show's inception in 1971. He built a 25-foot-long pit made from concrete blocks piled high in which he can cook the chickens without bending over.

“They put 25 [chickens] on at a time with 1,000 chickens being cooked throughout the day total,” Adelmann says. “That’s a lot of chicken, but everyone’s got to be quick because they sell out fast.”

The McArthur Eagles, who helps run the pit with Adelmann, start cooking at 5 a.m. on the day of the air show. When the fire is hot enough, they add charcoal to ensure they can cook all day long. The air show’s special sauce is the key ingredient that sets this chicken apart. But forget getting the recipe, the sauce is kept secret.

The Vinton County Airport, which hosts the aerial performance on the third Sunday of September every year, does not receive county funds to operate. Instead, it is funded and managed by its boosters, including former President Nick Rupert and current President Terry Stevens.

“We manage the airport, we pay the bills, do the whole nine yards.” Rupert says. “Without the air show we would not have the money to keep the airport open.”

About 70% of the air show’s profits go to keeping the airport operational. The chicken dinner plays an integral part; it is the only component of the show that brings in money besides donations from parking. Without the famous chicken, the airport would not be able to stay open. And without volunteers, there would be no show.

Rupert believes the show’s volunteers are the lifeblood of its operation. The workers and performers work for free, allowing the show to pull in all the money it makes from its chicken sales.

Around 35 to 40 planes performed in last year’s show, providing hours of entertainment. Some of the volunteers were even able to get a lawnmower to fly, Rupert says.

Rupert named the show’s skydiving team the “Screaming Chickens,” after the infamous meal. The team is run by Bob Church, who has jumped at nearly every Vinton County Air Show. “We just love doing it. And to me, it's a free jump and food, and you get applause. You can't beat it." Church says. In fact, when he missed a show due to surgery he had the chicken dinner delivered to the hospital.

Many the jumpers and pilots are just like Church. They fly and jump for free, not only because of their appreciation for the show, but for the taste of the chicken and its secret sauce. Rupert makes sure every pilot who flies in the show is sent home with a tank full of gas and a full stomach.

Nearly 13 years ago, Aaron Buckley made a leather purse for his wife, Erin, and set out on an enterprising journey — starting their own leather-working business.

Much to their surprise, when they posted pictures of the bag, friends and others began reaching out to see if Aaron would be willing to craft one for them as well, kickstarting their business.

Aaron left his comfortable office job, and they decided to live with Erin’s parents while they worked to launch a retail store, Erin says. Beginning with online-only sales, the two crafted their goods in a garage, the only space available to them at the time.

“It just spiraled out of control; like slowly, but surely, ended up being his full-time job and a couple years later, we had the retail store open,” Erin says. “We had a baby, bought a house, and he quit his job, like all at the same time. To start doing this full time at the time, seemed normal… but now, looking back, I would never suggest that.”

The business, River City Leather, was located in Gallipolis and had an inventory of various tote bags, purses, clutches and more, all handmade for custom order.

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, hit River City hard. Following the government-ordered shutdowns of stores all over the country, Aaron says that River City never saw a pick-up in patronage when they opened back up. Fortunately, their manufacturing contracts took off.

“We had a really big opportunity in 2021 to take on 30-plus manufacturing clients from another manufacturer who was basically shutting that part of their company down,” Aaron says.

This prompted a shift in focus for the business — from retail to manufacturing. The Buckleys chose to close their physical retail location and moved to a much larger space to continue setting up the manufacturing side of their interests. Although creating private label products for other businesses was not entirely new to them, a location change was necessary due to the new clients they received in a short period of time, Erin says.

As a manufacturer, River City creates a variety of products for vendors across the country; many of which are made from leather, its original focus, but its products are not limited to only leather-based materials. River City now works with vinyl sheeting, ink printing, coated nylon and more, depending on client needs.

River City recently invested $147,800 into its manufacturing facility in collaboration with JobsOhio, Ohio South-

ABOVE: Aaron (left) and Erin Buckley pause to pose in front of their Gallipolis company’s logo.

east Economic Development (OhioSE), Gallia County Economic Development, and the University of Rio Grande and Rio Grande Community College.

One of the items the Buckleys purchased, a new piece of equipment, helps make their operations as efficient as possible, Erin says. The new machine projects the patterns of pieces and cuts from the large sheet of leather or vinyl. This will significantly boost River City’s order capacity and reduce the waste from each project, Aaron says. Because the machine cuts the leather itself, River City will be able to produce many more products in less time, Erin says.

But today, even though they continue their manufacturing journey, River City still runs a small online retail store.

Manufactures and customers can find more information on rivercityleather.com, whether looking for a new leather bag or a custom piece.

Its bandmates may change, but the heart of Pure Prairie

When describing a rock band, the terms “longevity” and “stability” don’t necessarily come to mind. In fact, the average life expectancy of any band is seven years, according to film director and DJ Don Letts.

Rarely does a band — especially a rock band — manage to stay alive for more than a decade. Even rock legends, such as the Beatles, the Smiths, the Sex Pistols and Nirvana, have short lifespans. However, Pure Prairie League, a country rock band out of Waverly, has managed to smash this expectation.

Pure Prairie League was formed in Waverly in 1970. During the last 54 years, the band has released twelve albums and continues to tour, featuring an ever-evolving band roster.

The original foursome consisted of Craig Fuller on guitar and vocals, John David Call on steel guitar and vocals, Tom McGrail on drums and George Ed Powell on guitar and vocals. Before forming Pure Prairie League, they had all played together in various bands in high school. Mike Reilly joined the band offering bass, guitar and vocals.

“I had first seen Pure Prairie League play on Jan. 20, 1970, at Ludlow Garage,” Reilly says. “I said, ‘Man, I like what these guys are doing [...] I’d like to be in that band one of these days.’ Then two years later when I got back from England [...] I joined the band.”

He’s been with the band ever since and currently operates as the manager. Reilly was central in keeping Pure Prairie League alive all these years, according to Mike Patterson, a Waverly native and the Vice President of the board of trustees at the Pike Heritage Museum.

“Mike [Reilly] bought the rights to the name Pure Prairie League,” says Patterson. “Were it not for Reilly, over all these years, Pure Prairie League wouldn’t have lasted 50 years, but Reilly ensured that it did because he owned the name.”

Pike Heritage Museum recently celebrated its 40th anniversary in August 2023 and released a new exhibit dedicated to the band. The exhibit features a timeline of the band and assorted memorabilia such as photos, vinyl records and other merchandise.

The rise of Pure Prairie League is impressive, especial-

ly considering their particular sound and place. The four founding members — Call, Fuller, McGrail and Powell — were based in southern Ohio at the time of the band’s start.

There were virtually no bands that were playing the kind of music they were, Patterson says. “There weren’t a lot of country rock bands in the world,” Patterson says. “You could say they were one of the earlier iterations.”

The band’s first hit, “Amie,” was released in 1972 on its debut album Bustin’ Out. The album cover depicts a cowboy named Luke, who would appear on the rest of Pure Prairie League’s projects. The cover art was a Saturday Evening Post reprint by the famous American painter Norman Rockwell, which was made possible through their record contract with RCA.

“Amie” didn’t gain traction until 1975 after the band consistently performed shows at various venues. Today, the song has been listened to more than 79,810,700 times.

Now in its fifth decade of commanding stages across America, Pure Prairie League doesn’t plan on ending things anytime soon. With an album on the way – according to Reilly - and a tour on the calender, this country rock band is here to stay.

“I love this new record,” Reilly says. “We’re only doing 50 to 60 shows a year and that’s fine at this stage of the game. We’re old, but we’re not dead.”

Pure Prairie League’s music can be heard on almost any streaming services. Catch them on tour by visiting their website at pureprairieleague.com.

dalynn “Addy” McGuire sits in the crowd, watching eight-year-olds play piano and violin, girls in sparkly outfits sing Taylor Swift covers and an eclectically dressed 14-year-old play bass guitar. In a few moments, she will be onstage herself, wearing a pale pink dress and cowboy boots, the spotlight shining directly on her face, getting ready to hear the backing track to The Judds’ “Grandpa (Tell Me ‘Bout the Good Old Days).”

She’d been on the Monroe Kids Got Talent stage before. It was last year, when she won.

The show is now in its 37th year and has been the starting point for many musicians who hail from Monroe County. Monroe Kids Got Talent, a yearly event in March that showcase Monroe County youth between the ages of 5 and 20, is more than an average community talent show. The kids involved may not have intense training and Hollywood connections, but they do have highly sought-after skills at a remarkably young age.

McGuire is certainly no exception. Last year’s talent

show was the first time the 13-year-old self-taught vocalist performed in public, and since then, she’s become a bit of a star in her hometown of Woodsfield. She’s sung the national anthem at local high school basketball games and hopes to someday compete on America’s Got Talent.

“[The talent show] was fun because normally, I’m really shy about talking to anyone,” McGuire says. “I don’t like it. But with singing, it gives me a way to express who I am.”

In a sparsely populated area like Monroe County, there isn’t an abundance of opportunities for children to partake in the performing arts. The presence of choral and vocal education in the Switzerland of Ohio School District is nearly nonexistent until the high school level, so most young singers in the area, like McGuire, are self-taught.

It’s easy to imagine a future where McGuire moves on to bigger and better things, especially after learning of Lauren Price Napier, one half of the bluegrass duo The Price Sisters, who competed in Monroe Kids Got Talent—and won several times—between the years 2002 and 2013.

[The talent show] was fun because normally, I’m really shy about talking to anyone. I don’t like it. But with singing, it gives me a way to express who I am.

–Adalynn McGuire, a past Monroe Kids Got Talent winner

Similar to McGuire, Napier and her sister, Leanna Price, attended school in the Switzerland of Ohio School District, and Price says they considered themselves to be shy unless they were performing. Although they received lessons for their respective instruments in elementary school from a local music store—Napier plays mandolin and Price plays fiddle—they did not undergo any vocal training until college.

Now, Napier and Price are signed to McCoury Music, under which they released their debut album, Between the Lines, and made their Grand Ole Opry debut this year.

Napier says she owes a lot of her performing experience to Monroe Kids Got Talent. “As far as I’m aware, it was the only [opportunity to perform] available to us at the time, so it was a very big deal to us, and it was really fun.”

For the current generation of children competing in the show, Napier encourages them to just go for it.

“If you realize it’s not necessarily about feeling like you’re the best that there is or the worst, there’s no measure of that because it’s different for everybody,” she says. “But if it feels important to you, then you just have to do it.”

This sentiment certainly captures McGuire’s journey so far. After her showstopping performance that night, she walked home from the 37th annual Monroe Kids Got Talent with a firstplace medal in the vocalist category for her age group and the Artistic Excellence award for the entire show.

“[I’m] very excited and happy that I won again,” she says.

As McGuire star continues to rise, it is possible she may one day appear on TV, and Monroe’s show might just mark her original “Got Talent” victory.

For more information visit their website at onthestage.tickets/the-monroe-theatre.

It was the only [opportunity to perform] available to us at the time, so it was a very big deal to us, and it was really fun.

–Lauren

Price Napier, one half of the bluegrass duo The Price Sisters

FACING PAGE: Adalynn

“Addy” McGuire wears her first-place vocalist medal for her age group and holds her newly awarded trophy for artistic excellence and certificate of participation.

BELOW: This year’s contestants of the Monroe Kids Got Talent Show line the stage with their trophies, medals, and certificates.

In 1840, deep in the woods of Adams County, just south of present-day Peebles, Charles Matheny went hunting. During his trek, he stumbled upon the red, bubbling brook that traveled through Peach Mountain, dipped his hands into its clear waters, and drank. What he found would prove to be more valuable than any game — Matheny believed he had discovered medicinal gold.

According to Mineral Springs: Adams County Ohio by Stephen Kelley, Matheny spent the next few months returning to the spring, claiming the sulfurous water had cured his kidney disorder. Word spread of a magical cure-all and soon people from all over flocked to try the healing waters for themselves. Elias Matheny, the spring’s owner and a relative of Matheny, became frustrated with the sudden influx of interest. In response, he sold the land with the spring, which eventually fell into the hands of Hillis Rees. Rees took advantage of the natural wonder by constructing a two-story log hotel: Sodaville.

In anticipation of the hotel’s prosperity, some ambitious individuals purchased land south of the hotel, inadvertently creating a community that would later become Mineral Springs. Thus, the hotel became wildly successful in the coming years and gained recognition for its purported health benefits. By the mid1800s, guests had the opportunity to not only soak in the springs, but hike the mountain, play tennis or croquet and fish. In 1904, another entrepreneur recognized the hotel’s profitability and constructed a separate, smaller hotel near the existing one.

The success of the main resort peaked just before World War I, and it housed visitors from all over the country. Unfortunately, the war damaged the hotel’s good fortune. It changed ownership multiple times in

the 1920s, and by 1924, the hotel was beginning to fall apart, with many of the rooms left empty. It was beyond disrepair when it caught fire in April of that year, burning until almost nothing was left, the debris scattering as far as two miles away. The catastrophe was allegedly caused by a meat block that was placed too close to the fireplace. Although the smaller hotel remained unaffected by the fire, it, too, suffered a loss in popularity and was demolished in 1950.

Today, in addition to mineral spring, Adams County is home to several karst features, a landform susceptible to sinkholes. This is what Douglas Aden, a geologist at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, specializes in. In addition to sinkholes, these karst terrains also commonly contain caves and springs, features Aden helps to map when he finds them. Springs are more difficult to locate — according to Aden, for every 100 sinkholes, he might find one spring.

The sulfur spring of Matheny’s day is right against the Ohio Shale, a geologic formation that can primarily be found in eastern and central Ohio, separated into three units: the Huron Shale Member, the Cleveland Shale Member and the Chagrin Shale Member, the last of which can be partially found in Adams County. Water can’t easily pass through the shale, so it runs into the limestone, causing dissolution. As groundwater travels through the limestones below the Ohio Shale, it accumulates sulfur, which causes dissolution in the limestone and provides the sulfur content of the spring. But Aden warns against trying Matheny’s famous remedy.

“There’s sort of this misconception that spring water is inherently healthy,” he says. “And, you know, it can be fine. It can also be a problem. It’s unfortunately easily polluted.”

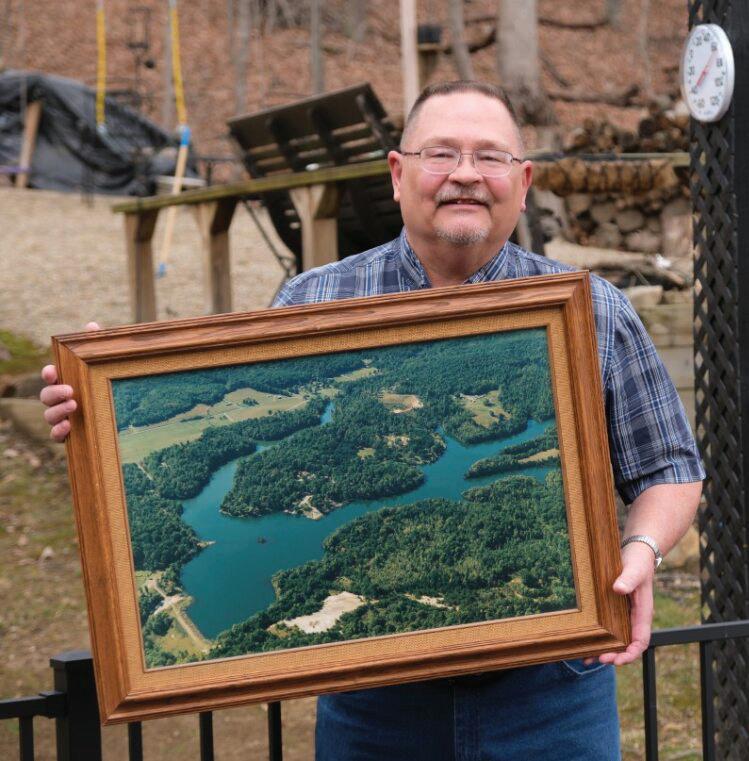

At the resort, campers can swim, fish, and rent kayaks, boats, golf carts and more.

If anything is spilled into a sinkhole, or if the sinkhole is used as a trash dumping ground, pollutants will leak directly into the spring. But the Mineral Springs Lake Resort is doing its best to keep up its reputation as one of the cleanest lakes in Ohio.

The sulfur spring of Mineral Springs Hotel is one of the 16 major springs that feed into Mineral Springs Lake, home to Mineral Springs Lake Resort. Although the Resort may not have any connection to the Mineral Springs Hotel of the 1800s, both realized the potential that the mineral-rich water holds.

Toby Smalley, the son of the resort’s founder, William “Billy” Smalley, says that his father always wanted to build a “resort.” The business opened its doors in 1973 with 60 campsites. The Smalley family, including Smalley’s mother, Phyllis Smalley, Smalley’s father and Smalley’s three siblings helped run the resort. The property ended up containing the largest privately-owned lake in Ohio, as well as one of the cleanest. “In the wintertime, you can go out and get your cup and just take a drink right off the surface,” says Smalley.

In addition to water’s purity, Smalley says the resort’s guests have stated that soaking in the water has provided them with arthritis relief and clearer skin.

While the benefits of mineral-rich water are somewhat unproven, it could provide some of the benefits that campers described. According to an academic article published in the International Journal of Biometeorology in 2024, the effects of balneotherapy—a practice that includes bathing in mineral water—could potentially reduce stress levels. Similarly, a 2017 paper published in Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine by researchers from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid states that a soak in sulfurous water in particular could have benefits for both skin and inflammation.

After William Smalley’s passing in February 2020, the Smalleys sold the resort to Tom Partin. Due to external factors, none of the Smalleys were able to take over the resort, although Smalley still holds a fondness for it. He takes pride in his mother and father’s work, as well as the role he played in helping them. William Smalley’s dream to build a “resort” has not only been realized, but continues to thrive — the resort currently has over 400 campsites.

“We were always proud that mom and dad had this and that we were a part of it,” Smalley says.

Adams County’s mineral springs have made an undeniable impact on both the county’s people and its history. Today, Matheny’s original discovery echoes throughout Peebles, as evident from the

sprawling Mineral Springs Resort on the aptly named Mineral Springs Road. There, one can also find the historical marker for the old hotel, just across from the springs. One might say that hope springs eternal in Adams County.

For more information: www.mineralspringslakeresort.com/

Bud Simpson, a columnist for the Logan Daily News, wrote about Lake Logan nearing its 70th birthday in 2023 and describes it as having “never seen a doctor.”

“It is paying the price right now for its neglectful treatment. It is slowly dying,” Simpson wrote. “There are large parts of it that have mere inches of foul water covering it and many more with less than a foot of water depth. This has caused its waters to warm considerably and those areas are now prime breeding grounds for weeds and the explosively invasive American Lotus.”

This was not news to Carol Mackey, one of various Logan citizens who had attempted contacting the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) to express concerns about the state of Lake Logan, but who wasn’t seeing action.

“It’s just a period of, really, neglect. Individuals had, over a period of time, called the state parks manager, called other responsible people within the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and were getting nowhere,” Mackey says. “Not that [the officials] were bad people or not doing their job. We like our state park manager a great deal — it’s just that he can only do so much.”

Maria Diaz Myers, another resident who lives near Lake Logan, moved to Logan in January 2023. Originally, she thought the lake looked OK — pardoning some dead lily

pads — so she says she was surprised when by late May, parts of the lake by her house looked like a swamp.

“I’m looking through my window thinking, ‘What the hell happened? It’s a swamp!’ And my neighbors were telling me, ‘Oh, no, you have no idea how bad this gets.’ It really does become a swamp,” Diaz Myers says.

Eventually, residents of the lake area met and voiced opinions about what needed to happen to save the lake, Mackey says.

Many of the lakes in Ohio are man-made and are owned by the state of Ohio. They are part of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ state parks and watercraft division. Most were constructed in the mid-1950s. Lake Logan, for example, was built in 1955.

But in recent years, the lake has faced increasing problems, such as a receding shoreline and decreased depth. Problems have been exacerbated by a lack of maintenance, resulting in overgrown vegetation due to the lake being filled with runoff and animal waste caused by organic material, Diaz Myers says. Last July, ODNR had planned to dredge the lake of excess silt. The plan was ultimately halted because there was not an adequate “dredge material relocation area,” according to the Logan Daily News.

By October 2023, the group of concerned residents formed the Lake Logan Association and eventually created a petition to save the lake — it now has over 4,500 signatures. The Association has since met with the chief of ODNR’s division of state parks and watercraft.

“When we had our first meeting with Chief Cobb and his staff, I asked the question, ‘Is it the state’s intent to restore this lake for recreational purposes, or do you want it to be converted to a wetland?’” Mackey said. “And without hesitation, [Cobb’s staff] said, ‘We want to restore it.’”

The idea of a civic association working alongside ODNR and local government to restore the lake is one that Diaz Myers says has worked in the past. Elsewhere in Ohio, associations like the Buckeye Lake Area Civic Association and the Lake Improvement Association for Grand Lake formed to represent the best interests of their respective lakes.

Listed in the Lake Logan Association petition, there are three main solutions for the lake’s restoration: dredging the lake, adopting a long-term management plan and fixing the damaged dam.

Dredging of the lake calls for removing years of accumulation of sediment from the lake to return it to its original depth. But Diaz Myers and the Lake Logan Association want a more sustainable, long-term solution beyond dredging.

“Dredging is like having surgery. And then if you go and you keep eating poorly, and you keep smoking, and you keep having this sedentary life, you’re going to keep having the same issue,” Diaz Myers says.

The Association calls for a “Long-Term Lake Management Plan” in the petition, ensuring timely maintenance, water quality testing and vegetation growth control. Finally, the Association wants the dam that serves as an outlet valve in the south end of the lake to be repaired. The petition also states that it is a necessity for the lake to be lowered to a winter pool, impairing vegetation growth and minimizing damage to boat docks.

“First and foremost, the biology in a stream tells the story of the water quality almost better than anything else,” Nathan Schlater, a senior director of ecological restoration with Rural Action, says.

There are a number of things that would be looked at for testing the water quality — one being the species living in the lake. Using indexes and protocol used by the EPA, a qualitative score of the water quality can be determined to see if there are any issues, Schlater says.

“Say [...] we look at the data and it says the fish population at this site wasn’t what it should be. Well, that immediately tells us that there’s probably a water quality concern,” Schlater says.

Main areas that a group, such as Rural Action’s watersheds team for example, would look at to determine water quality for a body of water like Lake Logan include the biology, bacteria in the water and its chemistry.

“For chemistry, for areas where there’s abandoned mine land issues, we look at PH, we look at dissolved oxygen, we

look at total suspended solids, I mean really we look at these in all areas. In mine areas, specifically, we look at iron and aluminum and manganese and acidity, and all of these different chemical parameters that say ‘Hey, here’s what’s going on in the water, and maybe here’s where it’s coming from,’” Schlater says.

While the association’s members feel strongly about the importance of rehabilitating the lake, they acknowledge there is a vocal minority who feel otherwise. Diaz Myers says she has encountered Logan residents who believe the lake is beyond saving and others who feel taxpayer money shouldn’t go toward the lake. She estimates that over 80% of Logan residents want to save the lake and extend its lifespan.

Both Mackey and Diaz-Myers emphasize the importance of Logan residents getting involved and standing up for their town’s interests, particularly when it comes to spending tax dollars on projects like Lake Logan.

“People aren’t accustomed to standing up and actively advocating for the community interest. I have seen that shift occur in my 28 years here,” Mackey says. “Community leaders are getting bolder and more aggressive in asking for our fair share.”

Aside from economic matters such as property rentals and tourism, fishing and the balance of flora and fauna around the lake could be negatively affected.

“At this point, if we don’t do anything about it, maybe we have 10 years left, and then you drive by it and it’s going to be a swamp,” Diaz Myers says. Restoration and maintenance, however, could extend the lake’s life and continue to protect Lake Logan.

When it comes to adequate housing for canines, the area’s county dog shelters are on a tight leash

by Trinity Trimble

It's an overcast Tuesday in February when Georgie prances through the front doors of the Athens County Dog Shelter. The small, golden-brown American bulldog gives a smile that splits his whole face as he prepares to introduce his new family to his old dog friends. He wiggles, his body trembling with excitement. However, Georgie's smiles quickly turn to barks as he watches his family hand him off and leave without him. He is a shelter dog once again.

Georgie is one of millions of dogs living in dog shelters around the U.S. The Shelter Animals Count — a national database tracking the number of animals in and out of shelters — found that 3.2 million dogs entered animal shelters in 2023. Of those, 2.2 million dogs were adopted.

Ryan Gillette, a lieutenant with the Athens County Sheriff's Office, supervises the Athens County Dog Shelter. He says the shelter usually houses 20-30 dogs, far above the ideal number of

12-15 dogs the shelter was designed for.

Gillette describes the job as a balancing act. He wants to house as many dogs as possible but needs to keep a few kennels available for dogs brought in from abuse cases, strays on the street or dogs returned from previous adoptions.

The Athens County Dog Shelter works to prevent overcrowding by partnering with rescue organizations, such as Friends of Shelter Dogs, to place dogs in foster homes until adoption. The shelter also attends several adoption events and places dogs on a waiting list if the shelter doesn't have enough room.

"When we're getting close to being overcrowded, the community helps out, comes together and provides resources until we can start to manage the numbers a little better," Gillette says.

Nonprofits and rescues work with shelters to get dogs adopted, fostered or transferred to other rescues. The Athens County Dog Shelter works with organizations like Bobcats of the Shel-

ter Dogs and BARC Ohio. The Pickaway County Dog Shelter works with Partners for Paws to get medical care for its dogs. The Adams County Dog Kennel works with Stop the Suffering and Animal Rescue Fund.

Donnie Swayne, the Adams County dog warden, says the rescues greatly help reduce the number of dogs in the county shelter. However, recently, there has also been less room at the rescues.

“We used to send five, six, seven dogs a week to rescues. Now, we’re lucky to send five or six a month,” says Swayne.

The Adams County Dog Kennel is currently overcrowded, and the current building, which was built decades ago, only has 10 indoor kennels. The shelter has been housing 20-30 dogs consistently for the past year. The overcrowding of the kennels has resulted in larger dogs living in outdoor kennels.

Luckily, Adams County has received approval to build a new $1 million facility to prevent overcrowding in the future. The new kennel will hold 40 dou-

ble kennels, allowing dogs to stay inside and outside. The new building will also include two offices, a bathroom and rooms for intake, adoption, veterinary care and quarantine.

“We’re going to try our best to make it better for our personnel and the dogs who are going to be in our pound,” says Ward.

The Pickaway County Dog Shelter also recently added to its facility. The shelter renovated its indoor kennels by adding laminate flooring and a new air conditioning system. It also built an entirely new outdoor kennel shelter to keep the dogs protected from the sun.

Preston Schumacher is the chief dog warden at the Pickaway County Dog Shelter. He says that the shelter used to have a major issue with overcrowding when he started working there in 2019.

“When I first started here, our average was 70. We had dogs in wire crates stacked high. Some dogs in our bigger kennels doubled up, two dogs in each,” Schumacher says.

Schumacher attributes the lower adoption rates to the increased advertising of dogs on Facebook and Petfinder. Currently, the shelter only houses 20 dogs. The shelter's max capacity is 41 dogs.

Gillette says one of the most significant issues for the overcrowding in

Athens County is the drop in adoptions since 2019 pre-COVID. According to The Shelter Animals Count, adoptions were down by about 100,000 in 2023 compared to 2019.

“The dogs aren't quite moving out of the shelters into rescues or adoptions quite as quickly as they used to in the past,” Gillette says. Though uncommon, some dogs can remain in the system for years before adoption.

Long stays in animal shelters can be extremely difficult for some dogs. The dogs are alone in 3 by 4 foot kennels where they can see and hear each other but not interact. The smells of other dogs blend together. Barks reverberate off the stone walls at all hours. Caretakers have to split the attention between each dog, so each gets little human interaction or time to exercise. Each dog may only be allowed outside once or twice during the shelter’s open hours.

“We have some [dogs] that start to deteriorate very fast in here,” Gillette says. “They [...] are just not comfortable in this type of environment.”

Schumacher says staying in a shelter can make many dogs’ behavioral issues worse. These issues can include fear, reactivity or anti-social behavior. Even dogs with no previous problems can develop them under the stress of long stays in shelters.

Potential adopters are urged not to judge a dog based on how it acts in its kennel. Some shelters, including Athens County, don’t even allow visitors to see the dogs in their kennels because it doesn’t accurately represent the dog.

Watching dogs deteriorate in the shelter can also be incredibly difficult for the shelter employees. The staff and volunteers get involved because they love dogs and want to help them, but seeing the dogs they care for at work struggle can result in compassion fatigue for the staff.

“We get dogs that are completely malnourished and have a complete turnaround and actually get a good adoption,” Schumacher says. “It makes the job worth it; it really does. But then you get the unfortunate part where sometimes the shelter environment catches up to a certain dog to where it makes them unadoptable.”

A dog becomes unadoptable when it becomes constantly aggressive and can no longer be safely handled by staff or released in good conscience to a home outside of the shelter. For the Pickaway County Dog Shelter, only severely unadoptable dogs — who show no signs of improvement — and fatally injured dogs are euthanized. In 2023, the Pickaway County Dog Shelter was forced to euthanize 8 of the 250 dogs that were brought to the shelter.

People can help prevent overcrowding and euthanasia in dog shelters by adopting from local shelters instead of buying puppies from breeders. Returning dogs can worsen overcrowding issues, so potential adopters should take the decision seriously.

"[Adopting] is a huge decision. It's one that shouldn't be taken lightly, but it can also be one of the greatest decisions that you could ever make,” Gillette says. “So, I would highly encourage everybody that's considering adoption to do a lot of research. Understand that you are taking responsibility for that life.”

Adoption can change the lives of dogs like Georgie. Georgie’s second stay in the shelter only lasted a few days before he was adopted into his forever family. He now lives in a loving home where he can run and play to his heart's content.

Ohio lies a tapestry woven with sto

The property for Cherokee Valley

Ranch expands across several fields, where the bison move depending on the season.

Bisond bonds between humanity and the land. We invite you to journey i n t o t h e heart of this landscape.

We invite you on a journey. On our first stop, discover the challenges and triumphs of starting a farm from scratch, where dreams take root in the soil. Then, roam the sprawling pastures of a bison farm, where the thundering hooves of these majestic creatures echo stories of heritage and conservation. Finally, consider the region’s agricultural roots. From first-generation farmers to veterans of the earth, we gain insights into a lifetime of struggle, wisdom and the changing tides of rural life.

From the rugged beauty of the plains to the rolling hills that whisper of generations past, these stories paint a vivid picture.

First-generation farmers settle in Southeast Ohio to labor the land and fulfill longtime dreams

by

Julie Sharp had nearly finished bush-hogging her pasture on a scorching day in August when she heard a familiar ping. Sharp instantly knew that the shear pin, which she had been struggling with all day, had come undone again. “I’m never going to be able to farm,” she thought as she trudged back to her new home. As she lay on the icy floor to cool her body and mind, she heard a knock. Pulling herself from the floor, Sharp wondered who it could be, and upon opening the door, she was pleased to see a familiar face. It was her neighbor, Wade.

“He got right under there, put the shear pin back on for me, and that was just really nice,” Sharp says. “You know, he just showed up right when I needed somebody.”

Sharp, 52, first dreamed of starting a farm while she was in college in Missouri. She studied animal science, which led her to work with general livestock. That was her first foray into farming, and it left a lasting impression. In June 2022, Sharp moved onto 25 acres of land near Somerset in Perry County. The land is hilly, which gives her sheep and two horses, Dolly and Fiona, plenty of exercise.

Sharp says she has found herself in good company. She expresses gratitude for her neighbors and appreciates the sense of community, despite being further apart in the country. They have been there for her since Day 1, Sharp says, recalling how her neighbors rode to her house on ATVs to say “hello” shortly after she’d settled in.

Sharp says she moved to Columbus about 20 years ago and worked for Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association (OEFFA), a nonprofit that certifies organic farms and educates people about organic farming, while she raised her kids.

Sharp divorced three years ago and lives alone at the farm, but her 21-year-old daughter is close while she attends Ohio University and her 17-year-old son visits on the weekends, living with her husband in Columbus during the week.

Part of the reason Sharp says she decided on Perry County was because it was only about an hour away from Columbus, so her son could easily visit, but it was also cheaper than flatter land because it’s harder to grow produce on it.

On her property is a home built in the 90s and a 160-yearold barn. She says she has not walked onto parts of the top floor of the barn because she could fall through, but bits of its history are still visible, from the original ladders, support beams and pulleys used to move hay. She says there is an opportunity to hold events like weddings or take senior pictures in it, but it would be a project for years down the line.

“This is what I’ve heard,” Sharp says. “The great thing about Perry County is that you can do whatever you want, and the bad part of Perry County is your neighbors can do whatever they want.”

Luckily, Sharp says she has great neighbors and does not have to live around any eye sores. They’ve even helped her like Wade did with the shear pin.

Molly Sowash and CJ Morgan, owners of MoSo Farm in Athens, have also felt a sense of community since Molly started the farm four years ago with just eight calves in residence. Now, they typically have around 25 cattle at any given time and raise 45 pigs per year.

The first-generation farming couple recently married, but collaborative hard work is nothing new in their relationship. They met about six months after Sowash started the farm while Morgan was flipping a house in Ironton. She would visit on the weekends and help him with the flip, and he would come up and help her on the farm. In December 2022, they officially became co-owners of the farm together.

The pair cleared out land that was owned by Sowash’s family and developed it into a place for their cows to graze. They make it clear that nothing that they have done would be possible without support from family and friends.

They use a technique called silvopasture, which puts trees into pastures for animals to give them more nutrients. Last April, they planted 510 trees in almost one day because of help from their friends. “We had a lot of volunteers, mostly for pizza and beer,” Morgan says.

Sharp also had to alter her land to make it fit for a farm. She installed a set of solar-powered electric fences to enclose

and separate the animals from each other while they graze and to keep predators like coyotes away. Sharp also has a chicken coop, but they stay separate from the other animals.

Dolly, Fiona and her flock of sheep graze on the hilly terrain Southeast Ohio is known for. Sharp has made improvements to the land, including converting a garage the previous owner used to fix old cars into a barn for her horses and 13 ewes. Sharp tells people that most of her farm is held together by the twine that strings her hay bales. But such things like easily movable metal fences for their pens are temporary while Sharp decides how to permanently set up her farm.

Although farming is a time-consuming practice, MoSo Farm is Sowash and Morgan’s 5-to-9 after their 9-to-5s. This is common for farmers because it can be difficult to make enough revenue to live solely on the land. Morgan and Sowash are used to this, though. Currently, Sowash works as

I wish someone was here to say, ‘When you take this fence down, walk that direction, not that direction.

–Julie Sharp, a farmer in Perry County, Ohio

the sustainable agriculture program director for Rural Action, a job that directly dips into her passion at MoSo farm and one she finds fulfilling. Morgan currently works for Wayne National Forest. He has a background in agriculture, having attended Hocking College for wildlife management and ecotourism, and once worked for Melody Holler Farm, where he learned about rotational grazing and regenerative agriculture.

Rotational grazing is a practice Sharp has introduced on her farm as well. Her 5-year business goal is to increase her number of ewes from 13 to 40 to bring in revenue. She chose sheep because of the size of the land she purchased. Originally, she wanted cattle. She had worked with cattle for years and studied them in school, but they require at least 60 acres of land, which was not available at the price and location Sharp desired.

Her current flock of 13 are due to give birth to lambs in May, which will be sent off to slaughter later this fall. She says sheep were a viable alternative to rotational grazing on a farm of her size. The rotational grazing is also part of Sharp’s plan with this farm because, to her, the wealth is in the soil.

Sharp says her rotational grazing technique will bring new plants, invertebrates, microbes and dung beetles, among other critters, that will increase the quality of soil. That quality will spread to the animals who will be healthier and have better tasting meat.

Sharp says building the farm has been exceedingly difficult, as she is new to the full extent of the experience, and she

can rely only on herself, some help from neighbors and advice from mentors she calls on the phone. The electric fences, she says, are great for keeping the animals in but have been one of her biggest pains to work with. Sharp says they typically take three hours a day to move.

“What I didn’t realize about this type of farming is there’s so much geometry to setting up your pastures and moving these fences in a way that you are not doing way too much work,” Sharp says. “I wish someone was here to say, ‘When you take this fence down, walk that direction, not that direction.”

Though many of her dreams for the farm have become a reality, Sharp continues to face setbacks. She had spent $2,000 on outdoor enclosures for her horses, but they were knocked down by wind in the winter and she recently had two sheep die. Both issues were major sources of anxiety.

Sharp's biggest lesson, she says, has been to stop focusing on future projects and remember why it was a dream in the first place.

She has always loved horses, and although the pair on her farm do not make her any money, they act as a different kind of revenue — joy. Each day, Sharps says she must decide whether to work on those hard future projects or decide to enjoy the day by going on a ride. Due to some farming

challenges, Sharp says she has not been riding in the last few months, but she will eventually return to the source of happiness that brought her to the farm in the first place.

Morgan says his last day punching a clock is April 19, after which he will work full time at MoSo. Sowash and Morgan say working long days at their day jobs and going into many hours working on the farm is nothing new to them, but for CJ, taking the leap to work full-time on his passion project has also been a source of anxiety.

“[There are] constant [questions] like ‘Is this the right choice? Crunching the numbers on our finances, I think we can make this much, what can we project?” Morgan says. “Passion wise, that’s a no-brainer. I feel like it’s something I almost have to do.”

What surprised Sharp most about farming was how evergreen it is and how that creates different gives-and-takes. Some mornings, Sharp wakes up with a plan for that day’s project, and by the afternoon she’s already thinking about something else despite looking at the same blueprints she woke up with. It’s easy for her to get ahead of herself.

“This is beautiful, right here,” Sharp says. “Even when the weather is bad or there are animals sick [I should] really stop and enjoy the moment I’m in.”

Perry County’s Cherokee Valley Bison Ranch needs no deer or antelope to feel like

Once balancing on the brink of extinction during the 19th century, American bison are making a remarkable resurgence. Due to the conservationists, farmers and ranchers who have been dedicated to growing and protecting them, the mighty mammals roam protected and private lands as symbols of conservation success.

For over a hundred years, many conservation groups have been formed, such as the National Bison Association (NBA), American Bison Society and Wildlife Conservation Society. “All these groups have, in one fashion or another, worked together over the years to ultimately restore the species to what it is today,” Jim Matheson, the executive director of the NBA, says.

Established in 1995, the NBA has pushed initiatives to celebrate the heritage of American bison while championing sustainable practices. Through collaboraton with stakeholders and advocacy for responsible ranching, the NBA has

secured the bison’s place in today’s world.

As the bison population thrives, surpassing 400,000, optimism grows for the future. “We’re in it for the long haul, we learned our lesson on the last near extinction,” Matheson says of the future of the bison population. “I don’t think we’ll ever go back there.”

The resurgence of bison is a testament to the power of collaboration and the enduring commitment to preserve America’s natural heritage.

Carie Starr, a native of Southeast Ohio, was drawn to the NBA due to her passion for bison and commitment to their well-being.

In 2005, a single meal at Ted’s Montana Grill would change Starr’s life and her family’s land in Perry County. Living on 50 acres that once belonged to her grandparents’ 160acre farm, Starr found herself enamored with the taste of bison. “I tried bison for the first time at Ted Montana’s Grill and it was love at first bite,” Starr says.

We’re in it for the long haul, we learned our lesson on the last near extinction.

-Jim Matheson, executive director of the National Bison Association

The experience would lead to the opening of Cherokee Valley Bison Ranch, a thriving bison farming venture she now manages with her husband, Jarrod.

The farm’s name pays homage to Starr’s Indigenous grandmother, Barbara Crandell. Starr’s grandmother originally owned the land and her heritage influenced Starr to name the ranch in her honor.

Back when Starr’s grandparents owned the land, they used it as a training facility for harness racing, a form of horse racing where a horse pulls a two-wheeled cart called a sulky. Around the mid-20th century, this was popular, enough that owners could win a lot of money from placing at events.

This is how they made money and kept the 160-acre farm running. Starr’s grandparents would use their land to train the horses they took to compete at competitions across the country. Revenue earned from the competitions supported their living costs and enabled them to keep the land.

“They used to go down to Florida in the wintertime and race at Pompano Park,” Starr says.

But raising, breeding and harvesting bison seemed like an impossibly difficult and expensive task for Starr. As a single mom without a barn or proper fencing for the animals, Starr says she believed her idea was improbable. However, once she met Jarrod, she shared her dream with him, and together they decided to take on the challenge. “Love makes you do crazy things so here we are,” Starr says.

Plans for their farm took a momentous turn when they saw an ad in the Columbus Dispatch for a herd of 14 bison. Originally planning to just look at the calves, the Starrs wound up buying the entire herd. However, they ran into a problem: they didn’t have fencing for the herd. Rather than walk away, they struck a deal and constructed the fencing in six weeks to bring the bison home for good. That original fence still stands today.

As the herd grew, so did Starr’s involvement with bison. “We went to an Eastern Bison Association event to buy some animals,” Starr says. “We decided that we needed to get involved in the organization because it's a great place to network.” It wasn't until 2017 that the Starrs decided to get involved with the NBA. Starr says the bison industry is a

community full of individuals more than willing to help one another, which is one of the big reasons Starr says she is so involved in it today.

On Starr’s 50-acre pasture, there is more than just her beloved bison roaming the fields — there are also people. Starting in 2019, Cherokee Valley Bison Ranch has ventured into agritourism, allowing visitors to camp on its land during the summer and fall months.

Whether one enjoys the bison as a site-seeing attraction or as a source of sustenance, farmers such as the Starrs have reintegrated the animal into Southeast Ohioans’ lives, and this time, it’s for keeps.

“Everybody is willing to share their experience so that nobody has to make the same mistake twice,” Starr says.

• Bison Ground: $13.75

• Bison Patties: $9.50

• Bison Brats: $15.00

• Bison Chorizo: $14.50

• Bison Sweet Italian Sausage: $15.00

Website: cherokeevalleybisonranch.com

Retail stores

• Kindred Market in Athens

• Strong and Co Restaurant in Somerset

• City Folks Farm Shop in Columbus

• Whitaker’s Market in Frederick Town

As the average age of farmers continues to increase, the agricultural industry must adaptstory and photography by Trinity Trimble graphs by Ryan Maxin

The gravel driveway to the branch of Corcoran Farms in Piketon winds through fields before stopping at a downward-sloping hill. A break in the tree line allows for a view of more farmland sprawling out in each di rection. The land currently only nurtures groundcover, but soy beans, popcorn, dent corn and wheat will grow in the spring. To the left are silos and pens for cattle preparing to be sold.

Daniel Corcoran, 60, runs Corcoran Farms with his broth ers Dennis and Timothy and his nephew Greg. Together, they operate farms in Pike, Ross and Scioto counties.

Before buying the land they farm in Piketon, they farmed it for 30 years under its previous owner, J. Madeira Brown, whose family had owned the land since 1805. Although he didn’t want to sell it, when Brown died, he didn’t have an heir to take over, so his daughters decided to sell the farm to Corcoran Farms.

Brown’s story is a situation familiar to many Ohio farmers who are aging and facing the dilemma of how to han dle the succession or selling of their property. Though many family farms continue to be divied to the next gen eration, some farmers have no one to take over, which has resulted in a de crease in numbers of Ohio farms.

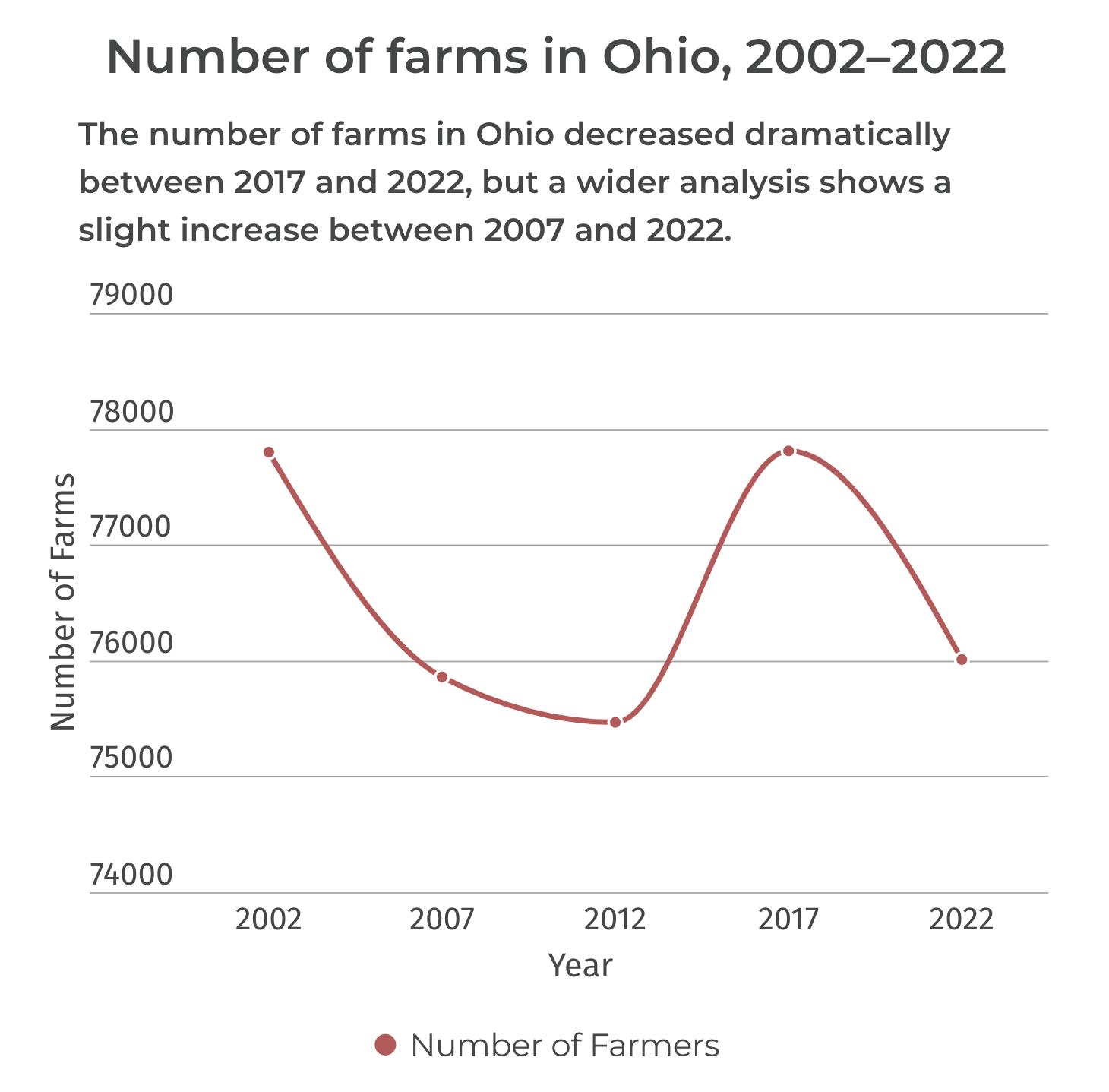

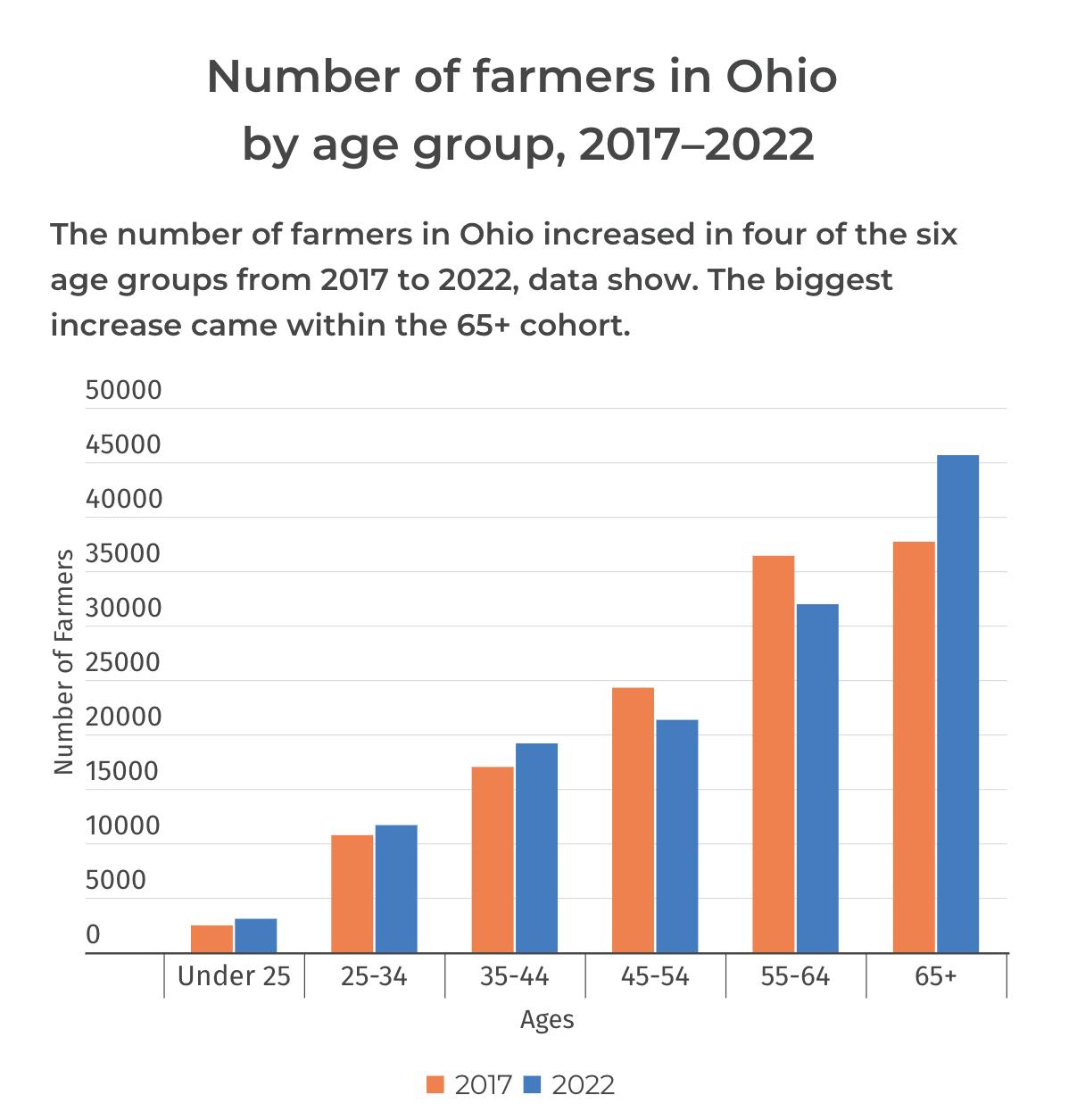

Between 2017 and 2022, the US DA’s Census of Agriculture found that the number of farms in Ohio de creased by 1,796 farms between 2017 and 2022. Many factors can contribute to this reduction.

Some farms became partnerships or merged into larger corporations. If a farm doesn’t have an heir, its owner might choose to merge with another farm to have a partner help with the more physically strenuous aspects of running the farm. The number of partnerships

and non-family-held corporations increased between 2017 and 2022.

Phillip Cunningham, 71, owns STW Farms LLC. STW Farms produces corn, soybeans, wheat and hay. His farm also pastures cattle and contracts a hog finishing operation. He says that he’s known of some larger farms and partnerships that have combined their operations.

“Large farms, when you scrape the dirt away, they’re probably brothers, sisters, cousins that have combined operations to reduce cost and make them more profit,” Cunningham says.

Farms are also being sold to corporations for housing, factories, highways and solar panel fields. In such cases, increased regulations, high operating costs, and unstable incomes may have made it financially difficult to continue to farm.

Corcoran explained that in farming, you can have really good years and really bad years. He says that without his wife, it would have been incredibly difficult to continue to pay the bills and support their family during bad years.

“My wife, Donna, has allowed us to do things [that], during those tough years, would have been extremely hard. But, she has kept the household together by having that opportunity to be out there working and bringing an income and insurance,” Corcoran says.

Family farms without a second income to rely on may have to sell their land if they suffer from back-to-back “bad years.” Land being sold has resulted in the loss of 312,949 acres of farmland in Ohio between 2017 and 2022. In order to prevent further loss of farmland, farmers in Ohio are encouraged to get involved in succession planning sooner rather than later.

The United States Department of Agriculture performed a Census of Agriculture in 2022 and found that the average age of farmers is gradually increasing. In 2022, the average age was just over 56 years old.

Senior farmers, or those 65 years old or older, made up 34.3% of all farmers working in Ohio in 2022, and, in line with the increasing average age of farmers, senior farmers are growing in membership. The number of senior farmers increased by 7,951 between 2017 and 2022.

The average age of farmers is increasing because many farmers don’t retire — sometimes because it’s not an option. Either they don’t have anyone to take over their farms, or they can’t afford the income cut that hiring someone to take over would require.

For others, retirement isn’t something they would like to do. Corcoran jokes that to farmers, retirement often has a much darker meaning.

“I’ve seen two retirements in my lifetime on the agriculture side. One was my dad when he passed on. He was still actively involved in making decisions on the farm. He wasn’t doing a lot of the physical, doing a lot more mentoring or advising. But, he had a heart attack. That’s one way of retire-

ment that I don’t think I want to go through … Then, the first time that we’ve actually had somebody retire was my brother last year,” Corcoran says.

Like Corcoran’s father, many farmers must take a step back from the more physical aspects of the farm as their health declines.

“The caveat on all things is health, if you’re healthy, you can grain farm and do lots of things for a long time. You may have to change your perspective if you have a health issue or your family has a health issue,” Cunningham says.

According to Cunningham, technological advancements in agriculture are allowing farmers to continue working their

ABOVE and BELOW: Data sourced from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Census of Agriculture.

ABOVE: In the fall, harvested grain will be stored in silos like these at Corcoran Farms.

land for far longer in their lives despite a possible decline in their physical health.

New inventions such as automated feeders, cleaning systems, tractors and crop sprayers reduce the physical labor required by farmers. New irrigation and seeding systems can also increase crop yields and reduce farming costs.

Cunningham says that because many farmers are self-employed, they don’t have the option of retiring or taking a step back from farming entirely. They rely on the income from their farms to live.

“Normally, you’d like to maintain the farm operation and your equity because as you get older, you don’t know the future and you need an income stream. It’s not, in some cases, a 401K, it’s your land or your operating profits,” Cunningham says.

But some farmers do choose to retire. If they have a family member willing to take over the farm and can continue to earn an income, they can afford to step back from the dayto-day operations.

After his brother Pat retired, Daniel and Donna sat down at their dining room table to discuss what retirement would look like for them. Donna explained to Daniel that instead of putting on her scrubs to go to her nursing shifts each day, she was ready to spend her days at home with their three dogs. She told him that she’d like him to join her. Corcoran is not so sure, though.

“She’s worked since we’ve been married, and she’s of the age that she wants to do something else, which is great. She’s talking about retiring, and that’s an area of unknown that we have to explore,” Corcoran says.

There’s a lot of young people ... who are interested in farming.

-Emily Elam, participant in Rural Action’s Incubator Farms program

Corcoran says he hopes his nephew, Greg, will continue running the farm once he and his brothers retire. “That’s the next logical step for Corcoran farms. If we all decide we’re going to retire one day, or some of us decide to retire, he takes over,” Corocan says.

Cunningham says that succession planning is going to be different for every farm. There is no one answer, and each operation will have to discuss what works best. “It’s a complicated issue. There’s a lot of attorneys, and there’s a lot of consultants doing work on this, and there’s probably only an individual answer,” Cunningham says.

Cunningham’s daughter Trish will eventually inherit STW Farms. Though Cunningham is running the farm himself, he has considered training someone to help run the day-to-day operations as needed.

Finding and training an heir is not easy. The money to pay the new farmer must come from somewhere. Cunningham explains that farmers looking to train an heir must either grow their farm or adjust to the additional salary being taken from the profit they live on. For many farmers, losing that money isn’t an option if they want to get by.

“It’s very difficult today to compete with the wages these young people can get. When you add an employee, you either have to do more [as a farm] or expand your business because you can’t take less. That’s why you’re seeing farm sizes grow,” Cunningham says.

For farmers looking to hire someone to take over their farms, there are many young people interested in farming, but don’t yet have the experience doing so. The Ohio Farm Bureau, college programs and organizations such as Rural Action are working to help connect new and experienced farmers.

Emily Elam is a site associate at the Chester Hill Produce Auction. Since 2023, she has participated in Rural Action’s Incubator Farms program. She says many young farmers lack the resources and knowledge required to begin farming.

“Most farm farmers in Ohio are middle-aged and they either don’t have kids that want to take on their land, their profession, or they don’t have the means to keep it going,” Elam says. “There’s a lot of young people, on the other hand, like myself, who are interested in farming or inspired to farm, but they lack the resources to do so. Our challenge in Ohio, and at nonprofits like Rural Action, is to help bridge that gap in any way that we can.”

Educating a new generation about farming will become increasingly important as Ohio’s farmer population continues to age. The older generation of farmers can help the agricultural community grow by passing generational wisdom down to their children and new farmers.

“People with experience, [the] established farmers, want to share their successes and their weaknesses. They want to build up the community and pass on the baton, one might say, of farming,” Elam says.

Corcoran helps to inspire a new generation of farmers by working with a nearby school to educate children on farming. The kids take field trips to his farm, where he teaches them about where their food comes from.

“You got to be active and do your part. I hope I pass that along to my children as well,” Corcoran says.

During the spring, people driving past Corcoran farms may see groups of children trekking down sloping hills, being driven through freshly green fields, and digging in the dirt. For some, a love for agriculture may begin to grow, just like the seeds under their feet.

Meet Amara Jackson, college student, future attorney and current National President of FFA

Amara Jackson grew up in Corunna, Michigan, racing and showing horses. She joined her school’s chapter of the FFA and was appointed as the National President of the FFA in 2023. Currently, she is attending Oklahoma State University, dual majoring in agricultural communications and agribusiness. After completing her undergrad, she plans to apply for law school to study farm succession and estate planning.

How are FFA students today going to impact the future of agriculture?

It’s the 21st century, and we’re learning that technology is a really great tool that we can use, and there’s constantly innovation. It’s exciting because our students are at the forefront of that innovation.

Why is the number of farms and farmland decreasing? I don’t know if anyone has a direct answer to that other than it is a tough industry to work for. But, that also is what brings people so much pride at the end of the day because [they know], ‘I completed my day, my job is done from the day I get to lay down at night knowing that some people are eating because of me.’ I think that pride, that excitement, and that passion for hard work is what keeps people going. But, I do think some of those external factors are what cause some individuals to stop farming.

Will technology help aging farmers continue to work on their farms

All these technologies are going to save farmers stress and farmers worries. And help save them physically, too. [Technology] will provide the opportunity for them to, hopefully, someday, continue farming for as long as they would please.

What do you see for the future of agriculture?

With all the technology and the policy and everything that can be changing or shifting, I do see agriculture as trying to lean into that tradition a little bit more, just to make sure that we’re not forgetting our roots and where we came from.

For more information: WWW.FFA.ORG