FIGH T ING FOR YOUR KIDS LIKE THEY ’RE OUR KIDS . CARE.

A parent will do anything for their sick child. So will we. Comer Children’s Hospital is dedicated to addressing the full spectrum of patient care needs — from common childhood illnesses to the most daunting medical challenges. We offer each the latest treatments and clinical breakthroughs because every child deserves to grow up healthy, happy, and strong.

To learn more, visit UChicagoMedicine.o rg /Comer

SOUTH SIDE WEEKLY

The South Side Weekly is an independent non-profit newspaper by and for the South Side of Chicago. We provide high-quality, critical arts and public interest coverage, and equip and develop journalists, artists, photographers, and mediamakers of all backgrounds.

Volume 10, Issue 12

Editor-in-Chief Jacqueline Serrato

Managing Editor Adam Przybyl

Senior Editors

Martha Bayne

Christopher Good

Olivia Stovicek

Sam Stecklow

Alma Campos

Community Builder Chima Ikoro

Contributing Editors

Jocelyn Vega

Francisco Ramírez Pinedo

Scott Pemberton

Visuals Editor Bridget Killian

Deputy Visuals Editor Shane Tolentino

Staff Illustrators Mell Montezuma

Shane Tolentino

IN CHICAGO

Voting in the April 4 runoff

In order to vote by mail for the April 4 runoff election, Chicagoans have until March 30 to register again to receive their ballot. Cook County Board Commissioner Brandon Johnson will face off with former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas. Since neither candidate received fifty percent of the votes in the February 28 election, this runoff will determine who is inaugurated in May. Almost a third of the Chicago City Council seats will also be decided by this election, including the 4th, 5th, 6th, 10th, 11th, 21st, and 24th wards on the South Side. Voters can register for their mail-in ballot online at chicagoelections.gov, or send in a paper copy of the application. Last year, the Chicago Board of Elections started giving voters the option to permanently receive a mail-in ballot. Residents who want to automatically receive their ballot each election can download the form for the permanent vote-by-mail roster at chicagoelections.gov/en/vote-by-mail. html and drop off or send it to Chicago Board of Elections, 69 W. Washington St. #800.

Discount Mall vendors face eviction

IN THIS ISSUE

the multi-million-dollar corporation “My wife, she said, ‘Huey, what they doing is inside trading.’”

emeline posner

ecps coalition wins a wide majority of chicago’s new police district council seats “Community control isn’t an idea that’s up in the clouds. It’s material.”

jim daley

op-ed: promising more police is a political calculation, not a solution

We need to decide as a society what policies are sustainable and work.

anthony ehlers

4

12

13

Director of

Fact Checking: Sky Patterson

Fact Checkers:

Eliza Billingham

Lauren Doan

Kate Gallagher

Kate Linderman

Layout Editor Tony Zralka

Special Projects Coordinator

Managing Director

Malik Jackson

Jason Schumer

Office Manager Mary Leonard

Advertising Manager Susan Malone

Webmaster Pat Sier

The Weekly is produced by a mostly all-volunteer editorial staff and seeks contributions from across the city. We publish online weekly and in print every other Thursday.

Send submissions, story ideas, comments, or questions to editor@southsideweekly.com or mail to:

South Side Weekly 6100 S. Blackstone Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

For advertising inquiries, please contact: Susan Malone (773) 358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com

For general inquiries, please call: (773) 643-8533

Nearly one hundred immigrant vendors at the Discount Mall, located by the Little Village arch, are facing eviction after the property was bought by developer John Novak in 2020. The site is a neighborhood attraction for Latinx families across the Midwest who like to visit on the weekends for imported goods and a fulfilling cultural experience—as well as for small entrepreneurs making a living. Novak has a portfolio of big-box retailers and originally expressed a desire to transform the plaza into a strip mall. But public outcry has thrown a wrench in his plans and many vendors are staying put. Vendors on one half of the building have until the end of the month to vacate and said they are being pressured to start moving out their merchandise as early as next week. But a group of organized vendors is working with the alderman and community groups to exhaust all of their options.

Pilsen Food Pantry moving

After operating out of a former Catholic church for almost three years, the Pilsen Food Pantry is finally moving to a new location at 2124 S. Ashland Ave. Evelyn Figueroa and Alex Wu first opened the pantry at the University of Illinois Pilsen Health Center in 2018. As shutdowns hit the city in March 2020, the Archdiocese of Chicago allowed the pantry to move in rent-free to their current location at the formerly-vacant Holy Trinity Croatian Church. Since then, the archdiocese has not agreed on any terms, and attempts to buy the vacant building have been met with “radio silence,” according to Figueroa. After a long search for different options, the pantry finally found a new home for its food pantry, clothes closet, little library, medical supply program, and more for the hundreds of mostly Pilsen and Chinatown neighbors who visit them each week. You can visit the CTAaccessible location on Saturday, April 1 from 11am–2pm, and keep up with their move at pilsenfoodpantry.com/newhome.

extra snap benefits ending this month Many families rely on the benefits and may see a decrease in COVID-related relief of over $200 a month.

savannah hugueley.................................15

reducen los depósitos de snap este mes Reducen los depósitos de SNAP en marzo. por savannah hugueley, traducido por jacqueline serrato 18

chicago youth organize townhall for mayoral candidates

“If we’re able to drive and hold a state ID, why aren’t we able to vote?”

erik uebelacker .................................... 20

the exchange

The Weekly’s poetry corner offers our thoughts in exchange for yours.

chima ikoro, valerie lee 22

Illustration by Bridget KillianThe Multi-Million-Dollar Corporation

After a five-year, multi-million dollar renovation, the Tudor Gables housing cooperative abruptly dissolved and sold. Board members blamed shareholders for the cooperative’s dissolution, but shareholders insist there’s more to the story.

BY EMELINE POSNER

BY EMELINE POSNER

This story is co-published with the Hyde Park Herald

This is the second of three stories about the Tudor Gables, a historic Black-owned housing cooperative on Drexel Boulevard. Founded in 1950, the building sold in March 2021 after millions were poured into renovations and building repairs. In March 2021, after a $3.4 million rehab project, the cooperative abruptly dissolved and sold. The Herald/ Weekly interviewed three dozen Tudor Gables shareholders, lawyers, contractors and neighbors and reviewed hundreds of internal emails and public documents about the rich legacy of the “castle,” as members fondly referred to the building, the conflicts that led to its sale, and the changing face of the boulevard.

This reporting was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

When shareholders gathered on the front lawn of Kenwood’s Tudor Gables housing cooperative in September 2021 to consider selling their building, they had just emerged from a several year, multi-million-dollar renovation.

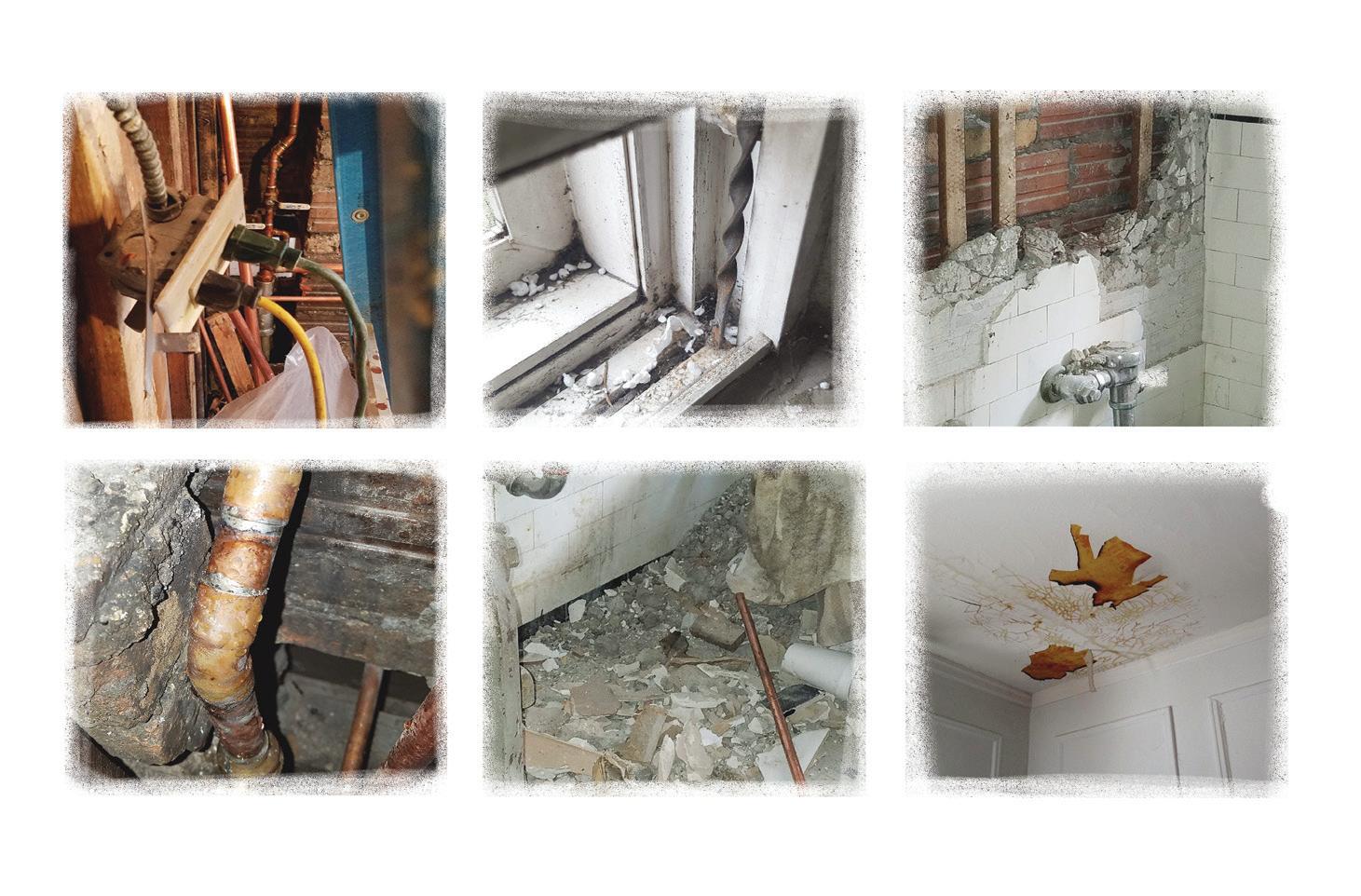

The renovation was supposed to get the historic cooperative’s 114-unit building back into shape. The building’s roof had started to fail in the mid-2000s and members were living with leaks and the damages wrought by continuous streams of water: electrical outages, mold and ceiling collapses.

promised to get the building back on track. But soon after the rehab’s completion, the board insisted that it had no option but to accept a developer’s off-market $11.5 million offer. At the meeting, members reluctantly voted to sell. “It was made clear that we didn’t have no choice,” said Kublai Toure, a member of fifty years.

The president of the building’s last board laid blame for the sale at shareholders’ feet. “The tragedy of Tudor Gables is that we had in our possession a beautiful building and could not maintain the cost to hold on to it,” then-president LeShuan Gray-Riley wrote in an email to members on April 1,

2021, a month after the building sale went through. “It was lost due to Shareholders not paying due assessments and without this income each month, it is impossible to pay our bills and mortgage.”

Members question this narrative.

Around two dozen interviews with former members and a review of loan documents show that the boards that governed the Tudor Gables over the course of the building’s multi-year rehab broke its fiduciary duty to its members, operating without transparency and allowing conflicts of interest and interpersonal disputes to derail the rehab.

Two board members convinced the cooperative to pay them $105,000 to oversee construction management, bringing in a general contractor who did poor-quality work that needed to be replaced, and at one point allowing teenagers to participate in basic construction work. By the end of the rehab, one board member had filed two lawsuits against the building; other board members were accusing each other of fraud and mismanagement. In the end, some shareholders had to wait years for a habitable unit; one was never able to move back in.

“A total manipulation,” William House called the board’s reasoning for the sale. He alleges that the board mismanaged not just the rehab but the sale itself, leaving seniors on fixed-incomes like himself struggling with housing instability after the building sold.

In November 2022, the board said that the last of the funds from the sale had been paid out to members and to outstanding bills: with the last of the money, the cooperative is gone. But House and other members still have questions about what transpired during the years of rehabilitation, and the board’s role in the sale. Who was responsible for the bungling of the rehab? Was selling the building really their only option? How are members to trust that what the board says is true? And what will become of the building that the Tudor Gables cooperative used to call home?

To House, only one thing is certain. “They stole a lot of money, and nobody

seems to know,” House alleges. “They need to be accountable.”

Going to court, going to court

No one disputes that shareholders had stopped paying assessments in the previous two decades. House was one of them.

House came to the Tudor Gables in 1980, when his father’s brother passed away and left his apartment and cooperative shares to his next of kin. His father had a home already, so House took the unit. The eighteen-year-old moved in and stayed, later falling in love with and marrying another member of the cooperative.

When the roof started to fail in the mid-2000s, House was one of several third-floor residents who got hit bad. Water got everywhere, dripping in through the ceiling and the walls with every rainfall and snowmelt. As House was putting out buckets and tarps, the board would only hire for patch jobs, he and other members said. There was no use repainting or rewiring; as soon as the latest patch job failed, the plaster would be bubbling up just like before.

Frustrated with the board’s inadequate response, House started calling 311 on the building. City inspectors added to the Gables’ growing list of violations, but that didn’t seem to spur the board to action. So he started withholding his monthly assessment of $370.

There was some precedent for not paying assessments, the monthly fee that cooperative members pay toward building maintenance, property taxes, and other bills. But it wasn’t always because of water damage. Back in the 1990s, House and other members alleged, the board started giving a pass on assessments to some members, “people that they was friends with,” House said. “They would tell people not to worry about [missing assessments].”

Kublai Toure, now a retired fireman and community activist, had lived in the building since 1972. He said that around the 1990s, the board became less transparent with documents. “A lot of people felt that communication was breaking down,” he said. “There was a great concern about that because there were certain [board activities] that we didn’t have full knowledge of.” Toure said he spoke up about his concerns surrounding transparency and building

upkeep for years, but eventually backed away from board affairs because of the distress it brought.

House said he didn’t want to piggyback on others’ opportunism. But when other methods of intervention failed, withholding his assessments appeared to be the only way to signal to the board that their neglect was violating his rights as a member of a cooperative—to say, “you all had an obligation and you didn’t fulfill your obligations” in a way that they might hear it. He withheld his assessments, waiting on the board to fix the roof.

Instead, the board left him an eviction notice.

Cooperative members are in a peculiar situation. They have an autonomy and ability to build equity that renters do not have. Monthly assessments go toward building upkeep and improvements, utilities, and bills, and any remainder might be redistributed back to them, rather than to a landlord’s pockets. If the building is run well, the building’s value might increase, increasing the value of each member’s shares. But they don’t own their units, like condominium association

If a landlord fails to make necessary repairs in a rental building, a renter can legally withhold their rent until repairs are made if they’ve provided adequate notice. If that landlord moves to evict the tenant for not paying their rent, it’s considered retaliatory and tenants can fight back in court. That’s a protection extended by the city’s Residential Landlord-Tenant Ordinance (RLTO). But the ordinance’s protections don’t extend to cooperative members, for the obvious reason that cooperative members are owners, not renters.

Without RLTO protections, co-op members technically don’t have the right to withhold payment over necessary repairs. According to Michael Kim, a Chicago-area attorney who specializes in condominium and homeowner association law, outcomes for cooperative members in eviction court can vary situation by situation and judge by judge. Withholding assessments over an uninhabitable unit is usually “not a good defense” in eviction court, he said. But there’s some gray area, Kim acknowledged. “Sometimes it depends on how the judge views it and how the argument is presented.”

House found some luck in that gray

Another longtime member who had been withholding her payments due to water damage landed in court with a less sympathetic judge, who told her that the damages didn’t justify her withholding assessments. She appealed the eviction order, but it was upheld. The judge told her that her only way to fight the damages was to file a separate lawsuit against the corporation. She chose not to. “I just want it to be over,” she said in resignation.

Cassandra Dixon, a lifelong member who was acting as the volunteer building grounds manager at the time, remembers being directed to change the locks on this member’s unit after the eviction order was upheld. “This is someone who had been there … a good ten years, you know,” she said. “She considered this her home.”

The Tudor Gables board filed 159 eviction cases between 2000 and 2020. Eighty-seven resulted in eviction orders. The rest were either settled or dismissed, with the exception of four cases whose outcome couldn’t be determined from court records. (The Herald/Weekly was not able to determine how many of these filings were tied to water damages.)

When I asked cooperative lawyer Randall Pentiuk about the rate of eviction filings at the Tudor Gables, wondering how it compared to that of other cooperatives, he called the numbers “alarming and indicative of a deeper problem.” Pentiuk is based in Detroit, but represents cooperatives throughout Chicago. He said that many of his cooperative clients have no record of evictions.

members do; instead, the corporation owns the units, and leases them out to its members.

A cooperative member’s proprietary lease is not all that different from a renter’s lease. It holds members to paying their assessments and it holds the cooperative to maintaining the building’s common elements—its wiring, plumbing, walls, and roof. If damages to the common elements affect members’ apartments, the proprietary lease places the responsibility for repairs on the cooperative. Otherwise, repairs fall to the member. But in the eyes of the law, the existence of a lease means that there’s still a landlord-tenant relationship between members and their elected board. If a member breaks the terms of the lease, the board can file for eviction.

area. His first eviction case in 2008 was dismissed when the board’s longtime lawyer didn’t show up. When the board brought him back to eviction court in 2011, the judge agreed that House could use the board’s breach of the “implied warranty of habitability” as a defense. In the end, House settled with the board, which allowed House to keep his membership and his apartment on the condition that he pay back $2,500, a significant reduction from the nearly $9,000 he had withheld from the building over the past five years, and agree to accept the unit in its current condition.

It wasn’t a total victory: House was still living in a damaged unit under an unresponsive board. But others who made the same defense in court came out far worse.

Rogue or negligent boards aren’t uncommon, though. Pentiuk said he’d recommend that members organize themselves and push for a resolution to force the board to action, and failing that, to force a special election to reboot the board. (In Michigan, cooperative members can petition the circuit court to remove a director who’s broken their fiduciary duty, though this is a “new and somewhat unusual” process, he said.) If all of that failed, then legal mediation or litigation would be the only way forward.

A handful of members filed lawsuits against the board in the 2000s. One said she filed a lawsuit because the board allegedly refused to provide her with copies of her shareholder’s certificate, but the suit didn’t go anywhere. Some of the building’s janitors filed personal injury claims or fair

Cooperative members are in a peculiar situation…Without RLTO protections, they technically don’t have the right to withhold payment over necessary repairs.

HOUSING

wages cases against the cooperative. But the Herald/Weekly could identify only one case, filed in 2019, that sought damages for the board’s failure to keep its members’ units safe and livable, its breach of the warranty of habitability, as it’s referred to in the courts. It was filed by a board member.

I got the sense from interviewing former members that filing a lawsuit would have been too extreme. Even calling 311 on the building felt like an act of betrayal because, in the end, the repercussions would be felt by members, not just the board. “We’re calling the city on each other, we’re calling the city on our home,” Dixon said. “Two things is going to happen. We gonna get violations, we gonna get fined, the assessments is gonna go up.”

And then there was the practical part. Filing a lawsuit is time consuming and expensive. And filing a lawsuit against your own cooperative? Legal fees on both sides would eat out of the building’s funds, funds that could be going toward building repairs.

The board didn’t seem to have the same reservations. “They kept burning off excess money going to court, going to court,” House said.

In 2010, members had had enough. They voted to conduct an audit of the building’s books from the last several years. An accountant came on to look at the building’s books. But the board wouldn’t cooperate or provide supporting documentation, so the auditor was unable to verify a majority of the building’s cash flow.

Dixon remembered the meeting with the auditor well. “He pretty much told us, ‘You guys need to pay more attention to what’s going on with your money’ … because a lot of the money he was looking for, there was no accountability for it,” she said.

That same year, the board finally hired a contractor to replace the entire roof; but he disappeared after replacing three of the building’s twenty roof sections, leaving the majority of the roof stripped. The management company covered the unfinished roofs in blue tarps. The City filed a lawsuit against the building.

During a snowmelt in January 2014, House’s ceiling collapsed as he and his wife were sleeping. He called the Channel 5 news station and began withholding his assessments once again.

Moving in the right direction

As soon as she was elected president in March 2014, Fran Froehlich jumpstarted building repairs. There wasn’t enough money in the building funds to tackle it all at once, so she started with electrical work and the replacement of the roof above House’s unit, which she singled out as “the worst” to city officials prosecuting the building.

“Just wanted you to let you both know that we are still moving in the right direction,” Froehlich wrote by email to officials that October. They had signed contracts with a mason and a roofer, and were awaiting approval of the building permit.

The City was eager to see building work moving along. “The roof is really bad, can we expedite the permit?” a City lawyer wrote by email to a Department of Buildings commissioner, according to records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. In the next few months,

to move into the historically Black cooperative. She resided in one of the most spacious of the Gables’s apartments, a fiveroom apartment on the third-floor that overlooked the boulevard.

Within a couple years of moving in, Froehlich started writing long, winding emails to the board, documenting the leaks and mold in her apartment, criticizing the board’s tendency to hire contractors who were not licensed or bonded, and warning the board to “do it right” with repair work.

She wrote on behalf of other members, often with a tone of righteousness. The building “is almost in a state of deterioration where it is becoming unhealthy to live here, particularly those of us on the third floor,” Froehlich wrote to the board in 2010, after the City filed its lawsuit. Sometimes her tone dipped toward disdain. “It is the Board’s choice whether or not six months to a year from now I get to say ‘I told you so,’” she signed off.

Complex real estate matters seemed like Froehlich’s bread and butter. She kept

little about herself and her professional background, members said. (According to property records, Froehlich herself and as a partner in a holding company purchased and resold over two dozen distressed properties across the South Side in the late 1990s.)

Dixon, for one, felt that Froehlich held some responsibility for some of the evictions that locked members out of their homes. She and others alleged that Froehlich assured members that they were within their rights not to pay their assessments if they had water damages, even though in many cases members who didn’t pay their assessments wound up in eviction court. “This person’s whole thing, their whole agenda, was to come there to get the building divided, and to become president of the board, and have control to oversee the money,” Dixon alleged.

House thought that some of the animosity toward Froehlich was borne of members who resented having lost control of the board. “If it wasn’t for her the building never would’ve come out of building court and it would’ve been condemned,” House said. “She was voted in and she changed things up and they didn’t like it.”

(Froehlich declined to speak on the record, explaining that a legal settlement prevented her from speaking about the building. She did not respond to additional requests for comment.)

the building completed the roof above House’s unit and fixed lights throughout the building.

By October of 2015, Froehlich had secured a $1.4 million loan and was promising members that the remainder of the roof would be replaced and “watertight” before the first snow. Then they’d get to work on rehabbing the most waterdamaged units.

Loan draw documents show work continuing mostly on schedule: by December, all but two of the roofs were complete, masonry work was underway across the building, and the board had gut rehabbed twenty units, which would provide “temporary housing for existing owner’s [sic] while their units can be restored,” according to loan documents.

Though she had lived in the building since 2004, no one knew much about Froehlich. She was an older woman, one of the first white members

tabs on every administrative hearing and circuit court case, encouraging members to read them, and seemed to know the right course of action at every juncture. As they applied for the first loan, Froehlich navigated legal and financial requirements with ease, coordinating with city officials to make sure the city’s lawsuit didn’t get in the way of loan approval.

Many saw in Froehlich a board president who was doing what needed to be done, for once. Perhaps her tenure would bring an end to the secrecy and mismanagement. “We thought this was a good idea when Fran came in,” said Jannifer White, who moved into the building in 2013, after her grandmother, a longtime member, passed. “She knew the right lawyers to get when people were getting evicted illegally. She seemed like the voice of the people.”

Others remained wary of Froehlich. No one knew where Froehlich’s real estate knowledge came from; she disclosed

When Froehlich did a walk-through of the building in March 2016, the city inspector and site manager were pleased. The roof replacement and thirty-five unit rehabs was nearing completion, just in time for the building’s building court date, and they expected that the work would resolve the building’s remaining code violations. Several months later, the City settled the nearly six-year case they had been fighting against the Tudor Gables and released its claim on the property.

With the roof replaced and the lawsuit settled, it seemed like some bridges could be mended. Froehlich approached Dixon and Means about hosting a building-wide picnic in 2017, and they agreed to help.

To Dixon, that picnic felt like a turning point. The front lawn had been off-limits for barbecues or recreation for as long as anyone could remember, but that day longtime shareholders, newcomers, neighbors, and even the building’s handful of renters came out in the hot July evening

No one knew where Froehlich’s real estate knowledge came from; she disclosed little about herself and her professional background, members said.

to eat and mingle. A few people grumbled about the upending of building tradition, but for the most part, the picnic felt celebratory. “I’m telling you, we barbecued. We had a good time. Everyone was happy,” Dixon remembered. “What made me feel so good was seeing the elderly people living in the building, seeing them come out and sit in they little area and they brought their chairs outside, and they was sitting on Tudor Gables lawn.”

Accept it or don’t accept it

Froehlich’s board had plugged the biggest hole, but getting back to steady ground would be an even bigger project. Units damaged by water were still unlivable, and some members were still displaced from their units.

It was 2017, three years after House’s ceiling had fallen in. The roof above his unit had been replaced, but the unit itself was still in disrepair, and there was no clear timeline for rehab. Instead, he eventually accepted temporary residence in the unit underneath his apartment, which he said was rat-infested. The board basically said, “accept it or don’t accept it,” House said. “I kinda had to do the best I can with clearing up the rodents and doing what I needed to do to make it livable for me.”

House wasn’t the only one waiting. Pia Johnson had moved out in late 2015, after her own ceiling fell in. When it became clear to her that repairs were not imminent, she decided to be realistic and signed a lease on an apartment on the North Side.

Both House and Johnson stopped paying their assessments after their ceilings fell in. This was the first time Johnson had done so. “I was always up to date with my assessments,” Johnson said, even as water leaked into her apartment over the years, damaging her art and furniture. “I always paid because I knew there was so many people that wasn’t.” But to afford a temporary apartment, something had to give.

The board would need more money to fix up these and other units, and it also desperately needed to pay off their first loan. The $1.4 million loan had a twelve percent interest rate and a one-year loan term that the board had already extended. Dixon remembered that they were struggling to make mortgage payments on time, and members were nervous about the

possibility of foreclosure.

So at the end of 2017, Froehlich’s board put in an application for a loan from the Chicago Community Loan Fund (CCLF), asking for $3.4 million.

From any angle, the loan would be significant. It was far and above the fund’s average loan of $624,031 that year. (The only group that would receive more money in 2018 was the Timeline Theater, which received $3,600,000 to acquire and rehab a new building in Uptown.)

The fund doesn’t ordinarily loan to market-rate cooperatives like the Gables, CCLF president Calvin Holmes said. Instead, they focus on limited-equity cooperatives, which are designed to preserve affordable housing; they often receive federal housing subsidies and have strict rules about how much membership shares can be sold for. But Holmes said that they consider lending to market-rate cooperatives “if anti-displacement is at play or if it’s naturally occurring affordable housing.”

Both applied to the Gables. The building had always been home to a good number of older, retired people, people who lived on fixed incomes and needed the affordability and close-knit community that the Gables offered. And while House’s monthly assessment for his two-bedroom apartment may have nearly doubled in the last ten years, to $657, but the building remained more affordable than most market-rate rentals in the area.

Just as the board was getting ready to close on the loan in March 2018, the newly elected board treasurer, LeShuan Gray-Riley, sent out an email questioning a payment of $34,000 to Angelo Rose, a planner who the board had hired to help with the loan application. Shareholders had only agreed to paying Rose $3,000 for initial consulting work.

At a tense board meeting that month, Froehlich scrambled to explain the snafu to shareholders.

Was the $34,000 a broker’s fee for Rose’s work on the loan application? Or was it an initial fee for a construction management contract that Rose had prepared? Froehlich wasn’t sure. Regardless, she paid it out swiftly, she said, because he had threatened to file a lien, a claim that a contractor can file on a property when they don’t receive payment for an invoice. A lien clouds a building’s title, and many

lenders will not lend until the lien has been resolved, either by paying the lienholder or by fighting it in court.

(The Herald/Weekly was unable to confirm the existence of a lien via the Recorder of Deeds. Rose declined to speak on the record and did not respond to additional requests for comment.)

Anyways, Froehlich added, the board realized it had “no possibility” of hiring Rose because they discovered that he did not have an LLC in good standing. (CCLF spokesperson Juan Calixto confirmed that this is a requirement for a project manager under a loan issued by the fund.) So, Froehlich continued, they’d replace Rose with board member Nuri Madina and herself.

The meeting erupted into protest.

Madina, an older Black man, was bought into the building in 2014, the year that Froehlich became board president. By 2015, he was a board member, and his two sons bought into the building soon after. According to Dixon, he had been trying to buy into the building for several years before then. “I was directed by the [previous] president to not show him any of the units anymore because they felt like he was only coming in for profit,” Dixon said.

Renting in the cooperative was a fraught topic. Cooperatives are supposed to be owner-occupied, and to restrict subletting to a minimum, but over the years subletting had become common. Some shareholders moved out of state and rented their units out to hang onto them. Others inherited units from family members but didn’t want to move in themselves, so they found renters.

Dixon felt it crossed a line to be coming into the cooperative with the intention of renting.

Shareholders had other reasons to distrust, or at least be skeptical of, Madina. Dixon said she learned Madina had been barred from practicing law following an investigation in the late 1990s. And while Madina did have a company, Work Ready, Inc., it described itself online as a temporary employment agency serving the hospitality industry—not necessarily the best fit for a complex rehab on a building with more than a hundred units. According to a report uploaded online by Madina, he had taken part in three construction management

jobs in the previous two decades: facade repairs on two business storefronts in North Lawndale, development of several singlefamily homes in Garfield Park and the rehab of two 24-unit affordable residential buildings in suburban Maywood.

(None of the Madinas responded to multiple requests for comment by email or phone.)

Dixon wasn’t convinced that Madina and Froehlich taking the contract would move the building forward. Despite the progress on the roof, Froehlich’s board hadn’t been sharing financial documents, and now there was evidence it had been making payments without shareholder approval. “You all right now still can’t tell us what we spent the last money on,” she said. “So what’s the difference gonna be when you all start getting paid? What more you all gonna show us if you not showing us now?”

Other shareholders at the March meeting expressed concern, and asked why they couldn’t seek out a different project manager. Froehlich stressed that there was no time to find a new project manager and that the price was right: Madina’s proposed contract was around $70,000 less than the total that Rose had proposed.

Faced with the worry that without a project manager they might lose the loan— and with no immediate alternatives— members eventually agreed to approve the contract.

On April 9, the board signed a contract with Work Ready, and ten days later CCLF signed off on the loan. The next day, the board paid off its first loan.

Froehlich stepped down as president, and board members elected a new president, Delores Garmon, from among their board of directors. The second round of rehab started shortly after.

The loan was supposed to fund the rehab and get the cooperative back to financial health. The building would fix up members’ units, in order to return displaced members like House to their apartments, as well as vacant units in order to sell them. The hope was that between bringing more people into the building and collecting more assessments, the Gables could find its financial footing.

Problems with the rehab emerged early on.

According to Froelich, the building’s

HOUSING

general contractor fell months behind on work and brought in plumbing subcontractors who did dangerously subpar work. Broken pipes patched with insulation and cement, improper soldering, things “would have created a leaking and a flooding disaster,” Madina and Froehlich wrote in a letter to the general contractor, OLN Construction Services, in October 2018 justifying their decision to bring in their own contractors to take over the work.

As with Madina’s company, there was scant trace of OLN’s previous work history; the two building permits issued to their name were for comparatively minor work. According to Froehlich, OLN was recommendation of Angelo Rose’s, who had said that OLN had done construction work for the prestigious Trinity United Church of Christ (where the Obamas attended); the Herald/Weekly could not locate records of that work, and neither OLN nor Trinity United Church of Christ responded to request for comment.

Dixon also recalled that Madina brought in teenagers to do landscaping and some basic construction work in the building during the construction period, between 2018 and 2019. In invoices submitted to the loan company, Madina refers to a “youth employment development” program specific to the building rehab and a report uploaded by Madina in June 2019 includes pictures of teens on the building premises. One picture shows four teens standing in the empty fountain bed around a flower planter. Another shows several teens wearing masks, pulling down drywall in what appears to be the basement, where there was record of asbestos.

Shareholders said they weren’t consulted about teen participation and thought that it was wrong. Gladys Means said that Madina wouldn’t hear their concerns. She also alleged that he had told concerned shareholders that, if anything happened to the kids, the liability would fall on the building—not Work Ready.

When asked for comment about Work Ready’s youth employment development program, CCLF spokesperson Juan Calixto wrote, “Unfortunately we cannot provide information about specific loans or borrowers.”

At the start of the project, House and Johnson saw that their units were listed in the plans for rehab.

But by April 2019, a year had come and gone since the building had first secured the loan, and House’s unit was just halfway done, according to documents the building provided to CCLF. Johnson’s unit hadn’t been started at all. Only twelve units had been completed.

The lack of transparency was confounding to shareholders. “We go through these rehabs. You know we have the units. But when they rehab the units, we were like, how many units did you rehab?” Dixon said. “They could never give us a definite amount of how many units that was vacant to what they rehabbed.”

In some cases it wasn’t even clear who lived in the apartments that were slated for rehab—or if they were vacant, one of the many units that had been returned to the cooperative via eviction order or a legal fight to reclaim the apartment from a delinquent or absentee owner. The documents were contradictory and inconsistent. In some documents, apartments were identified as “shareholder-owned,” “to be sold,” or “rented,” but it was not specified whether the unit was being rented out by the board or by a shareholder in absentia. An individual unit was listed twice or three times in a list of units under construction; in another case a rehabbed unit was identified as unit “4W.” The building only has three floors.

While House and Johnson waited, rehab work had started happening in units that weren’t designated for construction.

Dixon’s new upstairs neighbor was doing a full gut rehab of her unit, tearing out walls and replacing pipes.

In the fall of 2018, the board approached Dixon and their plumber about replacing a degraded pipe that ran through her apartment’s bathroom. She agreed, thinking it was a good sign. The work was supposed to take one day. But soon the scope of the work snowballed, and before she could say “yes,” the board and plumber had decided to fully gut her bathroom, tearing out not just the walls and fixtures but the tile floor. Dixon suspected it was to facilitate the upstairs rehab work, but was upset that it had happened without her approval.

By the end of the year she had new pipes, but the rest of her bathroom was never put back together. When the polar vortex of late January 2019 hit, the new pipes, uninsulated and exposed to the cold, burst.

Dixon’s bathroom would be repiped that year, but for the rest of her time in the building, she’d make it through without a functioning sink or bathtub.

In addition to financing the rehab, the loan from CCLF was supposed to help the Gables shore up its finances. The loan was structured so that the cooperative wouldn’t have to make payments on the loan until they had finished their construction work, or April 1, 2020, whichever came first. The expectation was that, during this time, the building would focus on rehousing members, increasing assessment payment, and selling some of its vacant units—all of which would get money flowing back to the building before they were on the hook for mortgage payments.

The situation with assessments was so dire that the building had hired a debt collector to work with members with unpaid assessments before the loan. But one year into the loan, assessment payment did not seem to have improved substantially.

Shortly before Gray-Riley was elected in April 2019, he circulated a document detailing the shareholder assessment nonpayment that had ballooned under Froehlich’s presidency: around $144,000. One shareholder allegedly owed $37,000 to the building.

In the document, Gray-Riley claimed that Froehlich had not only permitted shareholders to rack up debt, but broke the building’s bylaws by moving evicted tenants into other apartments, pre-warning shareholders of eviction filings and service of court papers, and arbitrarily withholding stock certificates from shareholders. Indeed, the building’s eviction records show some people were recorded as having received an eviction order in multiple consecutive cases, suggesting that eviction orders were not always enforced, or that some members were allowed back into their units.

“I want to make it clear that [I] am not against Fran,” Gray-Riley wrote. “She was very helpful when I first moved into the building. Like most of you, I felt she was a nice person and appreciated her taking care of our building. However, I began to see real problems once I became part of the board.”

Gray-Riley warned that with this level of assessment debt, the building would hover on the brink of foreclosure and utility shutoffs. “Tudor Gables relies

on regular monthly payments,” Gray-Riley wrote. “If we fall short, everyone of us will be in trouble. Missing just one monthly mortgage payments can result in the bank foreclosing on us. You need to know, they will not foreclose on just the people who are not paying but on the entire building. We will ALL lose our home.”

(Gray-Riley declined to speak on the record and did not respond to additional requests for comment.)

The board was supposed to be shoring up the building’s finances by selling the units it was rehabbing, but there was little evidence of that. Shareholders interviewed by the Herald/Weekly said they only knew about new members because they saw them coming in and out of the building, or heard the work being done in their apartment— like Dixon. But there’s no mention of Dixon’s new upstairs neighbor in loan documents, or any other new members, with one exception.

In July 2019, three months after GrayRiley was elected president of the board, two of his relatives bought gutted-out studio units on the cheap, paying a total of $3,500 plus the costs of rehab, which they were to fund out of pocket. Madina and Froehlich reported this to the CCLF in one of their documents, and acknowledged the relation between the purchasers and Gray-Riley. It’s unclear if these were the only purchase agreements, or if they were the only ones Madina and Froehlich chose to include in the loan documents.

Jannifer White felt that Gray-Riley was taking advantage of his power as president to buy up units for relatives. White started working with him to buy a unit for her mother-in-law, who needed a place, and was anticipating it going through. “We’re in heavy talks about [the unit] for three or four weeks, around the end of summer, getting ready to make a down payment… Out of the blue, even before the building was getting sold off, it was no longer available.” No further explanation was provided, she said.

More than one shareholder said board members were snagging units for family and friends, though the Herald/Weekly was unable to confirm these claims.

Dixon alleged that her new upstairs neighbor was the girlfriend of one of Madina’s sons; when her kitchen light fixture fell down due to apartment work upstairs, she said that she had found

Nuri Madina, Jr. upstairs working on the apartment, and that he came down to help fix her light fixture. Beyond that, there was little documentation to verify ownership of the unit: there had been no work permit issued for the unit, even though it should have received a separate permit from the Department of Buildings because it was not a part of the loan-funded work.

As the rehab dragged on, internal conflict began bubbling up.

After Gray-Riley became president, Madina filed a lawsuit against him, former president Garmon, and another board member, claiming that they had deliberately slowed down rehab work in order to retaliate against Madina and delay payments to his company.

In the same suit, he accused GrayRiley of breaching his fiduciary duties by clearing the assessment debt of his sister and of Garmon’s daughter, both of whom lived in the building. He also sought damages for the building’s breach of the warranty of habitability, and their failure to provide him money to repair the interior of

his apartment after the roof above his unit was repaired.

In the text of the complaint, Madina also acknowledged receiving the sort of treatment that was never on the table for other members interviewed by the Herald/ Weekly: after complaining about water damages in his first apartment, in 2016 Froehlich allowed him to transfer his shares to a larger unit in exchange for $10,000. He also noted receiving a “remediation credit” of a little more than $10,000 for the water damages he’d suffered in his first apartment, something no other member interviewed by the Herald/Weekly had received, and which he’d be able to transfer over to his new unit.

Madina filed a second lawsuit against the building shortly after, seeking more pay for his project management work. He was asking for an additional $22,500 on the grounds that construction delays had caused him to do more work. Building lawyers argued that there was no “factual or legal basis” for the claim, and that the lien was “wrongfully filed,” according to court records. Madina had filed multiple documents attesting to having been paid

in full, they pointed out, and had signed a document that waived his rights to file a lien. There was nothing in the contract that offered an extension or a guarantee of extra pay.

Shortly after, Gray-Riley’s board claimed that Madina and Froehlich were not paying their assessments. According to the eviction filings put in against the two in late 2019, the last the building would file before its sale, Madina owed the building $5,000, Froehlich $22,000.

The Herald/Weekly was unable to verify the claim against Madina with Madina, Gray-Riley. or the board’s lawyer. However, Froehlich acknowledged that she had not been paying her assessments for several years in a January 2020 email to shareholders. She claimed that she had advanced $15,410 to the building in “appliances, goods and services, janitorial supplies, office supplies, etc.” when the building funds were running low during her presidency, and that she should have been granted a credit to her ledger. She added that she was now withholding her assessments for the same reason so many other members had stopped paying their

assessments in the mid-2000s: because she was still dealing with leaks. (Froehlich and Johnson had identical third-floor units at opposite ends of the building, directly under the two gabled roofs. These two portions of the roof had not yet been repaired. In withholding her assessments, Froehlich likely broke the by-laws. Board members are not eligible to sit on the board if they are more than a month behind in assessments, according to by-laws and election documents.)

At a point, I accepted that reconciling these conflicting narratives and allegations would be an impossible task.

Froehlich had assured shareholders that the courts would let the truth come to light. “[The] court will decide the case on the evidence, not on hearsay and fabrications,” she wrote to shareholders by email.

But the courts never got a chance to decide any of the cases. All four lawsuits remained open until the sale of the building, and were dismissed through settlement only after the sale of the building closed. The Herald/Weekly could not access the settlement documents.

RE-WRITING THE SENTENCE

House was able to return to his unit in 2020, just about six years after his ceiling collapsed.

As before, he had been withholding his assessments, as a means of holding the board to completing the repair work in his apartment. Assessment nonpayment hadn’t been a problem in all that time, he said, but within a few days of moving back in the board came knocking to demand the years of backpay.

“You need to come downstairs and explain to us how you want to pay back this money,” House remembered the board telling him. And he agreed, on the condition that he could have a lawyer sit in with him. He didn’t trust the board to negotiate fairly. “It’s not a debt I’m settling, it’s an agreement, because you guys strung me along for I don’t know how long. I’m not just going to fork over money,” he told me. Eventually they agreed on a payment of $12,000 to satisfy the six years of nonpayment, probably around a third of what he actually owed.

A few weeks later, in August 2020, House opened a letter from the board announcing that they needed to sell the building. The board had received an offer from a developer for $11.5 million, the letter explained, and the investor wanted to close by December, in just four months.

“At the time, I’m like, well what did y’all take my money for?” House said. “You made me think this money was going to help, then you coming back to me saying we got to sell the building.”

The proposal to sell the building came as a surprise to shareholders—and some came away feeling as though the board was acting on information that the shareholders were not attuned to. The board insisted they had been approached by a developer. House, White and others are certain that the board was soliciting offers months beforehand.

House and his wife, a former real estate professional, spent many hours dissecting what had happened—with his unit, with the rehab, with the sale. “I seen each one of the board members … after saying they were gonna sell the building, they stack with the building with people with the same last name, first name different. My wife, she said, ‘Huey, what they doing is inside trading.’”

Gray-Riley did not respond to requests for comment. Kris Kasten, the board’s lawyer, refuted that idea. “As I remember

it, the potential sale of the property wasn’t something that was contemplated by the board at the time I was engaged [in January 2019], that was not an issue that was discussed,” he said.

The multi-million-dollar corporation

In a September 2020 board meeting, the board offered shareholders a choice: they could accept the offer, and the payouts individual members would receive for their shares, anywhere between $40,000 and $115,000——far more than they would have ever been able to sell their units for on the market, given the state of the building. Or they could vote against the sale, and the board would increase assessments, introduce yet another new property manager, and make changes to the by-laws.

Toure said that he felt there was no real choice for shareholders to take, even though he disagreed with selling the building. He felt that the building was selling for far less than it was worth. But the board wouldn’t put the building for sale on the market, to see if other buyers might offer more than the $11.5 million. Instead, they blazed forward with the offer they had.

In November, along with more than the required two-thirds of shareholders present, Toure voted in favor of the sale.

After the sale was voted upon, though, things once again went south. For reasons the board wouldn’t explain, it took until March to close on the sale.

The first payment to shareholders, which arrived later that month, was only around 40 percent of the amount that they were promised because of an unexpected $3 million holdback for tax liability determinations.

Shareholders felt betrayed that they hadn’t been alerted to the possibility of a tax holdback sooner. “We need the money now, because we need to move,” Dixon said to CBS news, when they sent out reporters to cover the conflict at the end of March. Shareholders had been given only three months by the board and the new owners, 312 Properties, to move out of the building.

One of the only documents the board shared with shareholders in advance of the sale was a cashflow statement, showing the bills and payments that the cooperative would make from the $11.5 million.

The statement showed tens of thousands in payments to contractors

and legal settlements, but included no information on which projects or cases the payments were tied to. There was an extra $50,000 paid to OLN Construction, the contractor that had allegedly botched its plumbing and electrical work during the rehab; a $10,000 severance payment to someone who had been working as a “debt collector” in the building. Several of the line items introduced more questions than they answered: $3,000 in refunds for “shareholder overpayments.” Then, there were two payouts for legal settlements, one for $22,000 and the other for $2,500.

“There was no transparency. There was none,” Dixon said. “Even with the money, the first check they gave us, they told us where the money was going to be in. There was no account number, no bank heading, just the number—the $3 million was going to be at [Beverly Bank and Trust]. It was as if someone just took a sheet of paper and just copied a heading or something.”

Dixon and her mother were able to find new housing just a mile away, in Bronzeville, but the piecemeal distribution of funds made it stressful to work with real estate agents, she said. She says that she feels lucky to have found a seller who was willing to wait until she had received all of her funds from the Tudor Gables.

They weren’t alone in struggling to find new housing. Some shareholders had to stay with family, others had nowhere to go, and remained in the building until mid-summer, when 312 Properties began a full gut rehab of the building around their apartments.

The $3 million holdback was distributed to shareholders later that year, lawyer Kris Kasten said, in addition to $2,000 in interest. The board and Kasten declined to provide the Herald/Weekly with closing documents or any other information than was provided to shareholders.

When shareholders received a letter from the board in November 2022, saying that they were sending out one last payment of $140–400 before “winding down the corporation,” Dixon called me, almost in tears with anger and frustration at the way the board had treated her and other members through the rehab and sale.

“You think you’re good and then you get an email and it stirs up everything,” she said. “It’s a never-ending thing with them. You did us wrong and you’re still coming at us with these bullshit letters, not showing us anything.”

The new owners, 312 Properties, started the rehab work in June 2021. As of press time, the building is still under construction. Through a spokesperson, the 4th Ward Office said that 312 Properties were projecting the building to be completed by April of this year.

Right before Gray-Riley was elected president, Froehlich had sent an email to shareholders encouraging them to run for open positions on the board. The email had been forwarded to me by a former member, and when I first read it, I paused at the sign-off line: “Please consider submitting your name for Board candidacy to become one of the seven Directors of this multi-million dollar corporation.” For weeks, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. In all my interviews with shareholders and the hundreds of pages of documents and emails that had been shared with me, I had never known anyone talking about the cooperative in this way, least of all Froehlich.

It’s not that the statement wasn’t true—of course it was. Such a gorgeous old building, in Kenwood, overlooking the boulevard? Courtyard buildings on the boulevard routinely sell for millions of dollars. And while some cooperatives may have different approaches to cooperative living than others, at the core of it is the practice of collective living, not capital accumulation.

Was it Froehlich’s way of trying to pull new members into leadership, to convince members that, in spite of all the distrust of the board, that there was still something to work with? Or was it investor talk, a suggestion of the sale to come?

Froehlich didn’t respond to request for comment about the email signoff or what it meant. Any conclusion I drew from the text of the email would be mere speculation.

Speculation had become a familiar discomfort in the process of reporting this story. Documents, receipts were sparse; former members of the board wouldn’t talk on the record; shareholders shared what documents and memories they had, along with all their theories of what had gone wrong.

Nearly everyone expressed certainty that the board was buying up units and finding ways to scrape away some extra money for themselves and their family and friends. But there was no hard evidence to show for it. I ran countless searches, filed public records requests, interviewed experts

KIDS & S TUDENT S

in cooperative law and accounting. But in the end, without access to the building’s internal documents, which the board had allegedly stopped sharing with its own shareholders, there were few questions that either I or they could definitively answer.

What does one do in this situation? Some shareholders said they had filed complaints with the city. House said he wished he had called the FBI on the board. Some said they still want to file a lawsuit against the board and the Tudor Gables’s new owners, for the board’s breach of fiduciary duty and for the losses they incurred throughout the last several years of the cooperative’s existence.

In the end, the fact was that the sale of the building represented immense loss to those who lived in the building and even to those who may never have heard about the building.

Some members said that the three months given was not enough to relocate all of their belongings. Gladys Means had to leave behind her piano in the rush to secure a new house and move in. Other members alleged that building security had been compromised, and that they found that their apartments and basement storage units had been broken into and cleared out as they returned to the building to collect their things.

Obituaries, photos, stock certificates, all the odds and ends that accumulate over a person’s life—“That’s the kind of history that was bulldozed when these people took over,” Johnson said. She wished that these

items could have been handled with more care and preserved, given the building’s importance in the record of Black history in Chicago.

But it wasn’t just loss of these belongings: it was loss of the community, of people who had spent a generation or more together, caring for each other and fighting, sometimes both at once. It was the loss of affordable housing, the loss of the collectivity that had allowed the members of the Gables to govern themselves and their living environment, in better times and in worse.

Like Dixon, Johnson said that the urge to understand what happened with the Gables is still present, but it’s overwhelming. “It’s so much,” she said. “I’m running a business, trying to get my life in a direction, it’s beneath my brain power [to keep fighting it].”

Toure, after residing in the Tudor Gables for half a century, now lives in Bronzeville. He still has questions about what happened, but he also wants to know what lies ahead for the building that used to house his cooperative. When will the rehab finish? Will members have a right to return under the new ownership? “I would move back in, if the rent were decent enough,” he said. “Why not, I’ve been there long enough, why should I leave?”

“I deserve the right to know,” Toure said. ¬

e Negro Motorist Green Book is an exhibition that highlights the histor y and legacy of “ e Green Book,” the annual guide that provided Black Americans with information on restaurants, gas stations, department stores, and other businesses that welcomed Black travelers during the Jim Crow era.

ECPS Coalition Wins a Wide Majority of Chicago’s New Police District Council Seats

Candidates backed by coalition organizers won majorities in sixteen out of twenty-two councils.

BY JIM DALEY, THE TRIIBEThis story was originally published by The Triibe. Reprinted with permission

At 63rd and Cottage Grove, an ebullient crowd of people was gathered outside the storefront headquarters of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (CAARPR), talking excitedly. It was nearly 9pm on Feb. 28, and the election returns that were rolling in already indicated that CAARPR’s allies were winning a clear majority of seats on the city’s newly created Police District Councils (PDCs). Upstairs, a rollicking party was underway in the building’s spacious grand ballroom.

“I think history was made tonight. We are one step closer to having a real democratic voice in the way our communities are policed,” Anthony Driver said as he walked into the party. Driver is an interim member of the Community Commission on Public Safety and Accountability (CCPSA), a civilian police oversight body that will work closely with the PDCs. “We’ve tried everything else in the city of Chicago . . . except for having actual citizens at the table. And today, that’s finally becoming a reality.”

Inside the second-floor ballroom, dozens of organizers, PDC candidates and their supporters shared a catered meal of fried fish and chicken and clinked victory toasts at the bar while a DJ played booming music. A live feed of election returns was projected above a dance floor that was full of people stepping, and later on, doing the cha cha slide.

The mood was joyful. Many of those in attendance were supporters of mayoral candidate Brandon Johnson, and his clinching a spot in the April 4 runoff added to the energy in the room.

The people in the ballroom had fought for years to get to this moment. Some had spent decades doing so. Spurred by the fatal shooting of Rekia Boyd by thenChicago police officer Dante Servin in 2012, they organized a movement that led to the creation of elected civilian councils and a civilian commission with police oversight powers—the first such bodies in the city’s, and the nation’s, history. By the end of election night, the candidates and organizers in the ballroom had won sixtytwo percent of the council seats.

The Chicago City Council passed the Empowering Communities for Public

Safety (ECPS) ordinance, which created the district councils and CCPSA, following not only years of grassroots organizing by CAARPR and its allies in the Grassroots Alliance for Police Accountability (GAPA), but also months of negotiations with Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who tried to block giving any police oversight powers to elected civilians, despite supporting it during her 2019 campaign. What came out of those negotiations was a compromise that gave some oversight powers to the CCPSA and kept some in the mayor’s office.

Each of the city’s twenty-two police districts will have a threemember elected PDC that interacts with the community and can make recommendations to local police commanders. Those district-level councils also nominate members of the citywide CCPSA and make reports and recommendations to them. They also are in charge of nominating people to fill vacancies on the district councils themselves (which may be necessary immediately after this election in at least one district).

The CCPSA, whose members are appointed by the mayor from among the district council’s nominees, sets goals for the police administrators, hires and fires COPA’s chief administrator, and nominates candidates for police superintendent, for

whom they can also set in motion a process to fire.

The day after the Feb. 28 election, CPD superintendent David Brown announced his intent to resign effective March 16, and for the first time, the CCPSA began a nationwide search for nominees to replace him.

In the Feb. 28 election, the coalition of organizers who helped pass the ECPS ordinance backed seventy-one pro-accountability candidates. Fortyone of them are likely to win, with more than ninety-eight percent of precincts reporting results and mail-in ballots being counted until March 14. Three additional write-in candidates aligned with ECPS organizers are also poised to win seats.

Nine of the three-member police district councils (PDCs)—the 6th, 10th, 12th, 15th, 17th, 19th, 20th, 24th, and 25th—will be entirely made up of ECPSaligned council members. Seven more councils—the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 7th,14th and 18th—will have two each, giving the ECPS coalition’s allies control of sixteen out of twenty-two PDCs.

“We got a majority of the district representatives,” Frank Chapman, a field organizer with CAARPR and one of the leaders of the coalition that got the ordinance passed, told The TRiiBE the next day by phone. He noted the coalition’s many “decisive victories, either all or twothirds of the representatives,” as well as the single seats won by ECPS candidates in the 9th and 11th Districts. “But the main thing is, we were victorious, and that’s great.”

Candidates backed by the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) won two-seat majorities in each of the 8th, 16th and 22nd police districts, and one seat in the 5th. The police union endorsed nineteen candidates

for the PDC races, seven of whom were elected. The FOP also spent $25,000 on two election attorneys (one of whom ran unsuccessfully for a seat on the 25th PDC) and spent $15,410 to support a candidate who lost his race in the 19th District.

Candidates who were not endorsed by the FOP but had other law enforcement ties won one seat in each of the 18th and 22nd districts, as did Mark Hamberlin, a candidate in the 8th district who has variously claimed and denied having FOP support.

“For the FOP even to be allowed to be the opposition is crazy,” Chapman said. “This is an organization who are diametrically opposed to this legislation to begin with. So their involvement, their support of candidates, putting out a list saying who they endorse, this is scandalous.”

The only reason the police union was running candidates for PDCs, Chapman said, was to “undermine it.”

former TRiiBE community engagement associate) Anthony David Bryant, who successfully ran on a pro-accountability platform and was also in attendance, called the night’s results a win-win. “The goal is to have accountability and bring more power back to the taxpayer, to the community [and] to the people,” Williams said. “Some of this stuff has to be led from the City level, but eventually when the power’s given back to the people, we’ll know that we’re doing what we’re supposed to.

Alan Chavoya and Lauryn Cross, members of the Milwaukee chapter of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR) who had traveled to Chicago to help CAARPR in the election’s final days, sat together beside the dance floor. “It’s historic, and it’s very impactful,” Chavoya said. “We always look to Chicago for inspiration, and seeing this historic step to getting community control is very motivational and very inspirational.”

Op-ed: Promising More Police is a Political Calculation, Not a Solution

BY ANTHONY EHLERSto be allowed to be the opposition is

“For

is an organization who are diametrically opposed to this legislation to begin with. So their involvement, their support of candidates, putting out a list saying who they endorse, this is scandalous.”

–Each PDC sends one member to quarterly and annual meetings with delegates from all twenty-two councils, where they report findings from their districts and make policy recommendations to the CCPSA. The PDCs also meet collectively to nominate CCPSA commissioners. The decisive victory for ECPS-supported candidates across a majority of districts means the coalition should be able to advance its agenda in those meetings—something Chapman says they fully intend to do.

“We have the majority of the votes,” in citywide meetings, Chapman said. “Which means, we will be able to push forward with our agenda, which is to use these councils and use our democratic option to say who polices our communities and how they’re policed, and to get more control of policing in this city.”

Inside the ballroom, Donnell Williams, a supporter of 3rd District candidate (and

“I think the conditions in Chicago give us a glimpse into what the future may look like,” Cross said. The ECPS victory in Chicago is an example organizers elsewhere can point to, she added. “Community control isn’t an idea that’s up in the clouds. It’s material, and something that’s already happened. This makes me really hopeful for the future and really proud of Chicago for trailblazing.”

Chapman said that winning a majority of PDC seats is not the end of the struggle in Chicago.

“We got to continue to have the attitude of defeating [the FOP] going forward,” he said, “because we cannot let them deny us the democratic option to have these elected bodies—something that we fought for for the last fifty years.” ¬

.

Listening to one of the candidates for mayor in Chicago’s upcoming runoff, you’d think that more police is the answer to everything that ails the city.

But how we police Chicago is more important than how many police Chicago has.

Paul Vallas wants to add another 500 cops to the Chicago police department. This is clearly not the solution to the city’s problems! Vallas is a longtime politician, and talks frequently about his experience in government. He does indeed have experience, but it’s of the wrong kind. It is in failed plans and outdated policies— approaches that abandon and ignore communities of color. These are policies that want the easy way out by simply throwing more police at problems.

We need to decide as a society how we’re going to view crime. Our policies are a reflection of our larger social and political values, and they need to change. Failed policies see crime primarily as a problem to be deterred through fear and punishment. We need to realize that crime is a socioeconomic problem that needs to be managed. There is empirical evidence that this approach is more effective at keeping crime rates low and reducing recidivism.

Police brutality and corruption costs Chicago taxpayers millions of dollars. By

2017, Chicago issued more than $700 million in police brutality bonds—debt taken on to cover the cost of police-brutality payouts. On top of that are the tens of millions more in legal fees from brutality cases. In 2020, Josh Tepfer, a partner at Lovey and Lovey who won exonerations for defendants whose convictions stemmed from arrests by corrupt CPD Sgt. Ronald Watts, told Rolling Stone in 2020, “By the time the city’s done paying out watts victims, the amount could be astronomical.”

The call to add more police to communities of color is a clarion call for the total occupation of poor neighborhoods. What some politicians and others don't seem to understand is that many Chicagoans, especially in Black and brown communities, do not trust the police enough to call them.

Politicians are lying when they say that the police prevent crime. They do not. Police are a response to crime. They maintain a crime scene, and pick up evidence. They are not a preventative measure.

Chicago police also rarely solve the crimes they are called to. Per a 2019 report, the solve rate for white victims of homicide in Chicago is forty-seven percent. For Black victims, it’s just twenty-two percent. That’s unacceptable.

In a 2021 law review, University of Pennsylvania researchers William Lauger

the FOP even

crazy…This

Frank Chapman, CAARPR organizer

We need to decide as a society what policies are sustainable and work.

and Robert Hughes found that nationwide, less than half of violent crimes and less than a quarter of property crimes had been solved in the previous decade. Police “have never successfully solved crimes with any regularity,” they wrote, “as arrest and clearance rates are consistently low throughout history.”

Paul Vallas says he would hire 500 more police with the $100 million that Mayor Lightfoot is spending on private security. That money should be spent on violence prevention programs and community investment. Communities like Englewood and Auburn Gresham should not have to fight to keep a grocery store! These areas need investment. Instead, city policy seems to be one of neglect and abandonment.

Solving the socio-economic problem of crime is difficult. But politicians need more creative, sustainable approaches. We have seen decades of this policy, and it's usually aimed at poor Black and brown communities, whose residents are disproportionately stopped and harassed by Chicago police. A report issued by interim Inspector General William Marbeck in 2022 concluded that Chicago policing shows when a police stop results in an officer using force against a Chicagoan, 83.4 percent of these incidents involve a Black person.

Black Chicagoans are 1.5 times more likely to be searched or patted down than people of another race. Cars belonging to Black people were 3.3 times more likely to be searched than cars belonging to white people. Officers were more likely to use force against Black people!e. Officers used lethal force in sixty incidents analyzed by the Inspector General’s audit, and NONE of those incidents target white people.

In 2022 law enforcement killed 1,176 people. It was the deadliest year on record for police violence, according to Mapping Police Violence. Of those, 132 people killed were cases in which no offenses were alleged. 104 were mental health or welfare checks. 98 cases involved traffic violations, and 207 involved allegations of non-violent offenses. That means that in forty-six percent of the cases in which police killed people were originally nonviolent incidents.

How is it that routine police encounters escalate to killings? Police killings are not only continuing, they are getting worse. In

thirty-two percent of the cases last year, the person was fleeing when they were killed. This should not be happening.

What we see in the report from Mapping Police Violence is that the racial disparities are systemic. Black people were twenty-four percent of those killed last

rate is twenty-five times higher.

In 2017, the Department of Justice concluded a year-long investigation into civil rights violations by the CPD that resulted in a federal consent decree. Since then, the CPD has consistently lagged in its compliance with the decree. A 2020 report

If we want less crime, better policing, and better relationships between communities and officers, then we need to understand that you cannot deter crime through fear and punishment. It does not work. We can clearly see that this policy has failed. We have to do the hard work of addressing the social and economic problems that are at the root of crime and unrest; things like inequality, exclusion, abandonment, racism, and a lack of political voice.

These reforms need to be aggressive, far-reaching and systemic. Justice is more than the absence of oppression. Many of the problems we see in poor communities are by design, and so it's by design that we must fix these problems. How we police is more important than how many police we have. ¬

year, while making up only thirteen percent of the population. Black people are three times more likely to be killed by US police than white people—and in Chicago, the

found the department missed seventy percent of the deadlines for reforms. It seems they aren't even trying to change, and accountability is next to non-existent.

Paul Vallas says he would hire 500 more police with the $100 million that Mayor Lightfoot is spending on private security. That money should be spent on violence prevention programs and community investment.

Extra SNAP Benefits Ending This Month

BY SAVANNAH HUGUELEYIn March, SNAP recipients will see the amount on their Link cards drastically reduced, meaning less food—and less fresh food—on their table.

SNAP, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, is a federally-funded, state-run program that provides a monthly food allowance based on households’ size and income. About one in six Illinoisans rely on SNAP to meet their basic needs; and that number does not even reflect the people eligible for the program who don’t receive it, those who just barely don’t qualify, or those who are ineligible due to their immigration status. Over 940,000 people are on SNAP in Cook County, making up almost half of all people using the program in the state.

Since April 2020, states have been giving SNAP recipients additional Emergency Allotment, or EA, payments on top of their regular benefits. But these payments officially ended this month.

With widespread job losses caused by the pandemic, many families would have been eligible for increased SNAP benefits. But SNAP offices were running at diminished capacity due to remote work, social distancing, and prioritizing enrolling people in the program for the first time. So instead of reassessing everyone’s benefits, the federal government approved EA payments which gave people the maximum benefits for their family size, regardless of their income.

EA payments were supposed to