We offer air quality solutions that enable you to develop data-driven action plans. Identify high emitters, educate the public, and evaluate and report your interventions. With iMCERTS compliant measurements, a leading air quality software platform and bespoke air quality models, we offer detailed insights to empower you to work towards reducing air pollution.

Publisher:

David Harrison

E: d.harrison@spacehouse.co.uk

T: 01625 614 000

Editor:

Paul Day

E: paul@spacehouse.co.uk

T: 01625 614 000

Design & Layout: Oli Bowden

E: design@spacehouse.co.uk

T: 01625 614 000

Business Development Manager: Andy Lees

E: a.lees@spacehouse.co.uk

T: 07843 632609

Air Quality News Magazine

published by Spacehouse Ltd

Pierce House

Pierce Street

Macclesfield SK11 6EX

Contact

T: 01625 614 000

E: hello@spacehouse.co.uk

All rights reserved. Reproduction, in whole or part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

I make no apologies for the fact that there’s a very international feel to this issue of Air Quality News.

Our Special Report looks at three fascinating pieces of international research into air quality monitoring, and they couldn’t be more different from each other.

The EU-funded PAREMPI project is a huge undertaking that is investigating how primary aerosols from the transport sector react in the atmosphere, and how much the secondary aerosols thus formed contribute to ambient PM2.5

On a completely different scale, See the Air’s Sotirios Papathanasiou has decided to monitor all the air he is exposed to for a full year. Here, he updates us on the early stages of his project and he will be updating his research for us as it progresses into next year.

Our final article explains how Albert Presto has managed to extract black carbon data from filter tapes sent to him from American embassies in Africa. His equipment is a mobile phone camera and a reference card.

Elsewhere, Emily Whitehouse examines the proposals contained in Zane’s Law and speaks to Zane’s father, Kye Gbangbola about their campaign.

Simon Guerrier takes a fascinating look at how a special effects company control the air quality in their bizarre workplace.

Also looking at air in the workplace (well, we have just had the 50th anniversary of the Health & Safety at Work Act), Martin Guttridge-Hewitt ventures into the professional kitchen to find out more about the Global CookSafe Coalition.

Our Big Interview is with Tim Dexter, the Clean Air Lead for Asthma + Lung UK, who have been making the headlines recently with some headline-grabbing campaigns ensuring that the issues around air quality continue to be discussed.

Darryl Johnston brings us the sad story of David Bolton, who fought in vain for his right to clean air. Having suffered from, and campaigned against residential wood burning, David died shortly after having decided to relocate to a cleaner neighbourhood.

Finally, Tony Abate from AtmosAir Solutions looks at the air quality challenges in transforming commercial spaces to homes.

Paul Day | Editor

We are connecting the dots of a new mobility revolution that is transforming our towns and cities.

With the broadest end-to-end portfolio of intelligent traffic management solutions, we work with cities, highway authorities and mobility

operators to make their road networks and fleets intelligent, enhance road

and

PAGES 6-7

News

Air quality coalition to launch Global Open Air Quality Standards.

PAGES 13-23

Special Report

Air Quality Research. A Special Report by Air Quality News

PAGES 22-23

Special Report

Democratising air quality data at nearly no cost.

PAGES 28-31

The Big Interview

We talk to Tim Dexter, the Clean Air Lead for Asthma + Lung UK.

PAGES 8-9

Legal – Zane’s Law

It’s time to inspect land before allowing people to live there.

PAGES 14-17

Special Report

Can an air expert escape air pollution? A year-long experiment.

PAGES 24-25

Air Quality Conference

Full line-up of speakers confirmed for National Air Quality Conference.

PAGES 32-34

International

The story of an anti-wood burning campaigner with no happy ending.

PAGES 10-12

Health & Safety Gone Monstrous!

How a special effects company survive the chemicals they work with.

PAGES 18-20

Special Report

PAREMPI dives deep into transport emissions.

PAGES 26-27

Kitchen Nightmares

A look at the work of the Global Cooksafe Coalition.

PAGES 36-38

Transforming Commercial Spaces to Residences

The impacts on indoor air quality.

A coalition of major players in the air quality field have come together to standardise the way the world talks about indoor air quality, developing transparent air quality standards that can be understood anywhere.

Given that the world currently measures in µg/m³, ppm or ppb and has a variety of Air Quality Indexes setting a variety of Air Quality standards, the arrival of a unified standard is long overdue, and this is where GO AQS comes in.

The Global Open Indoor Air Quality Standards – developed by scientists, public health professionals and air quality experts – will set clear, easy-to-understand thresholds for air quality indoors.

GO AQS will launch in December, by which time the thresholds will have been finalised.

The GO AQS guidelines will classify thresholds into 1-hour, 8-hour, 24-hour, and 1-year mean values, ensuring protection against both short-term spikes in pollutants and long-term exposure.

The standards will be available in two tiers. The GO IAQS Starter offers a basic compliance framework requiring minimal investment. It focusses solely on PM2.5 and CO2, both of which can be accurately measured with low cost sensors.

The second tier, GO IAQS Ultimate, will also include thresholds for carbon monoxide, ozone and formaldehyde.

‘GO AQS aims to be a valuable tool for the public, private sector, and academia alike,’ they explain. ‘Organisations that adopt

these standards can enhance the health and well-being of their employees and customers, while simultaneously reducing their environmental footprint.’

The main committee members at GO AQN are: Christos D. Argyropoulos (EUC, Cyprus), Mazen Jamal (Spacium Consulting, Sweden), Nathan Wood (Farmwood Ltd, BESA, MNIBME, UK) Rohit Chakraborty (UKHSA, UK) and Sotirios Papathanasiou (See The Air, Spain).

The committee is supported by a number of Advisory Experts (including the UK’s Prof. Catherine Noakes and Prof. Prashant Kumar).

GO AQS will focus on indoor air for now, but intend to turn their attention to ambient air quality in the future.

Scientists have found microplastics in the olfactory bulbs of over half of the human brains they examined, suggesting that they entered the body through being inhaled.

While the fact that microplastics can make their way into our bodies is already known, it is believed this is the first time they have been found in the brain.

The brains of 15 adults were examined at the São Paulo City Death Verification Service and microplastics were found in eight of them.

A total of 16 different synthetic polymer particles, ranging from 5.5 µm to 26.4 µm in size, were identified, with polypropylene being the most common. Polyamide (e.g. nylon), polyethylene and polyethylene vinyl acetate were also found.

These materials are commonly found in packaging and clothing.

The research was led by Professor Dr. Thais Mauad and Dr. Luis Fernando Amato-Lourenco from the University of Sao Paulo and Freie University Berlin.

Professor Mauad said: ‘Sixteen particles may not seem like a lot, but beware, they are relatively large particles, even if you call them microplastics. This means that there are almost certainly a lot of nanoplastics in our brains that are a thousand times smaller.

‘What is worrying is the capacity of such particles to be internalised by cells and alter how our bodies function.’

Maria Westerbos, Founder of Plastic Soup Foundation who supported the study said: ‘Plastic has become as synonymous as air is to breathing. Time and time again scientists are peeling back the cover on plastics’ dangerous effects on human health. There can be no further doubt.

‘The international community is only months away from the final Global Plastics Treaty negotiations, and yet policymakers are giving into the petrochemical giants. The international community cannot waste any more time, they must finally listen to science, once and for all.’

More than 500 million metric tonnes of plastic are produced every year and, of the 16,000 chemicals involved in the process, more than 4,000 are considered hazardous to human health and the environment.

Among the myths surrounding EVs is that the car will need throwing away after a few years, when the battery fails. However, new research, carried out by Geotab has now revealed that electric car batteries can last for 20 years or more.

Geotab examined the batteries of nearly 5,000 fleet and private EVs, with around 1.5 million days of telematics data and found that batteries were degrading by about 1.8% a year, considerably better than the wear on drivetrain components in an ICE vehicle.

A battery’s degradation is seen in its declining ability to hold a charge.

Geotab explain: ‘An EV battery’s condition is called its state of health (SOH). Batteries start their life with 100% SOH and over time they deteriorate. For example, a 60 kWh battery with 90% SOH would effectively act like a 54 kWh battery.’

In some of the cars tested, the battery was seen to be degrading by as little as 1% a year. They also found no evidence

that increased mileage was associated with increased battery degradation.

Geotab’s David Savage said: ‘Batteries in the latest EV models will comfortably outlast the usable life of the vehicle

However, we still see battery reliability being used as a stick to beat EVs with. Hopefully, data like ours can finally put these myths to bed.’

Liverpool City Region Mayor Steve Rotheram has announced that formal planning process has begun for what would be the world’s largest tidal power scheme.

Over the last three years, the authority has undertaken early technical work to develop the potential scope of the scheme, which could be up and running within a decade, playing a huge role in the region’s push to be net zero carbon by 2040 – at least a decade ahead of national targets.

The barrage scheme would be the first of its kind in the UK and could generate clean, predictable energy for 120 years and create thousands of jobs in its construction and operation.

A barrage traps water at high tide and releases it at low tide when it passes thought turbines which capture the energy.

The Mersey Tidal barrage would be the largest tidal range scheme in the world, the ‘range’ being the difference in height between the high tide and the low tide.

The design also incorporates a first-ever cycling and pedestrian route over the river between Liverpool and Wirral and could also provide a defence against future flooding risks associated with climate change.

A lagoon option was also considered but it was determined that a barrage would be less expensive, requiring less material and lower levels of government support.

Calls for a voucher scheme to give fairer access to cycling

A Sustrans survey has found that 38% of people earning people earning £17,000 or less would like to cycle but are prevented from doing because of cost.

The charity propose a scheme similar to Cycle to Work, through which vouchers costing around £18m a year could help 100,000 people on low income to get into cycling, while offering significant benefits to the economy by improving people’s health and access to work and education.

World’s largest carriers launch heavy-duty EV charging pilot

Some of the world’s largest shippers and carriers, such as Microsoft, Maersk and PepsiCo, will test long-haul heavyduty battery-electric vehicle operations along the 830 mile I-10, between Los Angeles and Texas. TeraWatt Infrastructure will serve as the strategic charging solutions partner for the project, providing infrastructure, including software, operations, and maintenance support, at six of its owned charging hubs along the I-10 corridor.

An air-powered propeller has been tested on one of Dubai’s abra ferry boats, used across the Dubai Creek. They found that the pneumatic system provided an extra 6% propulsion force and a saving of 307 kgCO2 a year, over its electric counterpart. The ferry’s predefined stops also allow for regular recharging of the compressed air, a much quicker process than recharging electric systems.

By Emily Whitehouse

What goes into landfill has never been such a contentious issue. Only last month the Environment Agency were accused of being a ‘reluctant regulator’ in the on-going row over the air pollution caused by Walleys Quarry in Newcastle-under-Lyme.

Support is growing to enable greater transparency over the land people’s homes are built on. Emily Whitehouse examines the proposals contained in Zane’s Law and how it could benefit home owners across England.

If you are involved in the air quality sphere you might well have heard of Kye Gbangbola and Nicole Lawler, the people advocating for Zane’s Law – legislation that they hope will become the first to protect communities against toxic landfill. Any such law would represent a justice of sorts for Zane Gbangbola, who tragically lost his life 10 years ago as a result of contaminated flood waters polluting his home.

The law was first proposed by Zane’s parents at COP26. It proposes that local authorities and The Environment Agency should keep a full and regularly updated register of any land within their area that may be contained. Councils should also be required to inspect any registered land that could be contaminated and the non-disclosure of information about risks to public safety from contaminated land should be criminalised.

Kye Gbangbola, Zane’s father, explains: ‘Zane’s Law is about protecting people, very much like the Clean Air Act. We felt the need to create it as we never want anybody to go through what we did. People should be able to access information about the land they live on. Just because some toxins are invisible, it doesn’t mean people can’t seriously be affected by them.’

Zane died in 2014 but, as Kye explains, the story begins in four years earlier. ‘In 2010 The Environment Agency were involved in the construction of a new property, no more than 10 yards from our home,’ he says. ‘A geotechnical report said there was an unacceptable risk of injury or even death coming from migrating landfill gasses, so they put a gas proof membrane in the property.

Zane was seven years old when his home was flooded. The waters had passed through a toxic landfill site and delivered Hydrogen Cyanide into the house. The entire family was hospitalised. Zane died and his father, Kye, is paralysed from the waist down.

‘However, none of the other properties in the area had any protective measures, so they were left exposed to the harmful gasses. We didn’t even have any idea they existed as public information stated the land was clean.’

In 2014 major flooding hit the South of England, and the basement of Kye’s home was filled with water. Water that had passed through a toxic landfill site situated behind the house.

‘It was terrifying,’ Kye says. ‘We lived in a Victorian property that was prone to flooding, but it was only ever the basement that was affected and you could just use pumps to clear out the water. However, in the early hours of 8th February, me and my family were removed from our house unconscious. I don’t recall experiencing any symptoms, whatever happened to me was pretty instant. The last thing I do remember is my wife and my son watching the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics, and I was working on a book I was writing in the next room. The last thing I heard before falling unconscious, was my wife screaming for help for our little boy.

‘When the fire brigade turned up on the scene, they forced everybody to evacuate their homes, people were taken to hospital and our entire area was cornered off. When I woke up in the hospital, I was in a very sorry condition, completely confused and dazed, but this is where my wife told me that our beautiful son, Zane had died.’

While Kye was in the hospital he was suffering an extreme skin reaction and about 12 hours after the incident, he began to slowly loose sensation in his legs. After 24 hours he had lost all feeling in them. However, it wasn’t until months later that one doctor diagnosed rhabdomyolsis caused by hydrogen cyanide poisoning.

‘After the accident an inquiry was launched where some of my neighbours said the fire brigade woke them up and told them they had detected traces of hydrogen cyanide,’ Kye says. ‘However, on the night of the incident an emergency COBRA meeting was called, where the government issued a statement claiming Zane died from carbon monoxide poisoning from an old petrol pump that was used to clear some of the water that had flooded our basement.’

After the statement was made, Zane’s parents accessed public health documents which confirmed firefighters found hydrogen cyanide traces their home. Since then, the couple have campaigned relentlessly for the implementation of Zane’s Law and an Independent Public Inquiry to be held to look into the death of their son.

‘The purpose of the inquiry is to identify what should go on his death certificate,’ Kye says. ‘At the moment, not only does it say he died from carbon monoxide poisoning, but the coroner also claimed Zane died a day earlier than he did.’

Kye continues: ‘The support we’ve received from the public, various organisations and authorities regarding Zane’s Law and the Independent Inquiry has been really overwhelming. The Fire Brigades Union and Unison have pledged their support for the inquiry and now that Labour are in power, we feel more hopeful than ever that it will go ahead. In 2019 Zane was included in the party’s manifesto, which called his death a “huge injustice” and since Labour have been elected, Keir Starmer has spoken out for Zane on numerous occasions.

‘A child’s death should never be a political matter, but when it comes to Zane, I’m pleased to see discussions are happening. Currently, we don’t have a timeframe for when the inquiry will happen, but we are doing everything we can to push for it.’

Alongside these efforts, Kye points out that five councils across England and, as of 9th September, the Green Party, have accepted Zane’s Law as one of their policies. He says: ‘Lewes were the first council to accept the law in February and I’ll never forget that day. The local authority accepted the law unanimously to a standing ovation. Brighton and Hove City Council were the second to accept the law in March and Adur District Council followed on the same evening. Lately, Stroud and Worthing have become the latest councils to accept the law with open arms.’

It all seems positive that more and more councils are climbing onboard with the idea of Zane’s Law, but Kye remarks he won’t rest until it has received Royal assent.

‘Among all the pain me and my wife have experienced over the last ten years, something that has brought me a little bit of joy is when councillors come together, despite what colour they’re supporting, and agree that more needs to be done to prevent people from living on or near contaminated sites.

‘Statistics show 80% of people in the UK live within two kilometres of landfill and yet I bet the majority don’t even know it. If we can get Zane’s Law passed it would really help present and future generations. I know it would also make Zane happy. Me and my wife have been environmental campaigners for quite some time and when we used to go and speak to schools and if Zane was on holiday, he would begin our presentations. I miss him every day, but I hope I’m doing him proud by campaigning for justice.’

To follow the campaign, scan the QR code or visit: www.truthaboutzane.com

By Simon Guerrier

Award-winning prosthetics in TV and film are made using hazardous chemicals. Neill Gorton at Millennium FX tells us how he keeps his staff safe from the creatures they’re building…

How do you make a monster? You’ve probably seen one of those programmes on TV, or included as a DVD extra, where they show how it’s done, interviewing the experts in prosthetics and special effects. There’s latex and animatronics, and a lot of skilled, painstaking work. Sometimes we might see people working in masks and other protective gear as they conjure these things into life. Yet it’s rare for behind-thescenes features to mention a vital element of such work –the quality of the air.

‘Given the range of what we do, we work with a massive variety of materials, many of which can be hazardous to health,’ says Neill Gorton, co-founder and CEO of Millennium FX, which has won BAFTA and Royal Television Society awards for its extraordinary creations. ‘We do everything from the bodies you see in realistic dramas such as Silent Witness to the creatures in Doctor Who,’ explains Neill. His team has transformed Kenneth Branagh into Boris Johnson, aged up Pierce Brosnan for 2023’s The Last Rifleman and made horns, cyborg prostheses and a tail for singer Lady Gaga.

What exactly are the hazards of this kind of creative work?

‘In moulding and casting, we use a lot of fibreglass and polyurethanes that are all toxic at some level,’ says Neill. ‘We laminate with epoxy resins. Even working with clay and plaster produces a lot of dust. You think of clay as quite benign but it has a lot of silica in it so there’s a risk of silicosis. The dust from MDF woodwork can be carcinogenic. Anything in the atmosphere can be a real problem.’

Acknowledging these hazards, let alone addressing them, is relatively new in the industry. When Neill started out as an assistant in 1987, there was little understanding of the health risks. ‘I can remember people smoking at work while they spraypainted stuff with an aerosol, breathing in cigarette smoke and whatever came out of that can. The company I worked for had what they considered a mould-making room, which had one small fan in the window. A bunch of people worked there constructing things out of fibreglass, none of them wearing masks. You had workshops full of people cutting, grinding and sanding, throwing all this dust and muck into the air – and all breathing it in. There was no air flow or extraction. And they’d mix up various chemicals without even wearing gloves. Exposure to polyurethanes, particularly isocyanates, can be horrendous.’

Things are very different now – so what changed? ‘I think it slowly crept in as the industry grew. Special effects has always been a cottage industry of small workshops, converted garages and units. Our company was like that when we started, with two small rooms in a workshop barely 500 square feet in size, a few benches and a handful of people. A big extraction system is a sizeable expense so I can see the temptation to go, “We’ll just open a window…”’

Today, Millennium employs 14 full-time staff across two sites, one in Cornwall and the other in Aylesbury, the latter comprising a building with 10,000 square feet of space. It can take on as many as 60 freelancers at a time for particular assignments, all of them working with potentially hazardous materials. ‘We’ve spent a lot of money on high-quality extraction systems in both sites,’ says Neill. But he thinks this reflects a wider trend in special effects as the industry has expanded.

‘Partly that’s because with bigger-scale operations you have healthy and safety people to oversee that kind of thing,’ he says. ‘But also people are smarter about the risks to health. When I started out, we just weren’t really aware of these problems. Now everyone takes it seriously.’

What does Millennium do to keep people working on site safe? ‘We have dedicated working spaces with big extraction systems.’ Indeed, as we speak to Neill over Zoom – he’s sat in front of shelves of various disembodies heads – there’s a constant, reassuring thrum from those very systems. ‘We also have big metal-walled spray-painting booths, the biggest one about 2m by 4m. The walls are fitted with filters and spark-proof fans so we can suck out solvent-based sprays. The same system will draw out dust and fumes, for example when we’re working with fibreglass. As well as spray booths we have individual extraction units, including ones we can move around and put next to whatever we’re working on. Then the staff all have personal PPE. Everyone puts on a respirator whenever they’re working in proximity to these kinds of chemicals and fumes.’

The team were regularly wearing PPE at work before the Covid pandemic struck and were able to carry on working during lockdown. ‘Yes, we were lucky there,’ says Neill. ‘Other bits of film and TV production had to shut down. The one job that kept going was [satirical puppet show] Spitting Image, because you didn’t see the puppeteers during the performance so they could all be masked up while recording. The individual sculptors on that nearly all worked from home anyway, so when they’d sculpted a new head someone would collect it from them and drop it off outside our building. We had a large, ventilated space and the right PPE so we could keep working.’

That, surely, shows the benefit of being an early adopter of this kind of process. What advice can Neill give to anyone else considering air quality in their workplace? ‘It’s something I get asked about a lot,’ he says. ‘I run an MA in prosthetic effects at Falmouth University, I’ve been a visiting professor at Bolton University for the past 10 years and I do consultations for other universities as they’re thinking about setting up workshops or similar spaces. I’ll look at their facilities and advise on what’s practical.’

‘The main problem with our kind of work is that it involves a lot of different processes,’ he continues. ‘In a normal factory environment, you have a production line of single processes that get repeated: there’s the spot where you cut things and the spot where you join them, then the spot where you spray them. You can tailor your extraction system to each of those tasks.

But we might use a spot to spray stuff and then the next week the same spot is used for cutting and grinding fibreglass. Or it might be used for working with expanding polyurethane foam that produces loads of gas. We might not know what we’re going to be working with on that particular spot, which means the space has to be adaptable and cover all these kinds of issue. Colleges and universities are exactly the same: they can’t afford to dedicate spaces to particular, individual processes as they might sit unused for days or weeks at a time.’

Another issue arises where existing space is converted for this kind of use. ‘With universities, the buildings I visit are often not brand new. The people I see have been given a certain, preexisting space and want to use it for certain processes. I then advise them on whether that’s really practical. For example, you need a big extraction system to suck up the air from the space in which you’re working and pump it outside through an exhaust. But the further that air has to be pumped, the less effective the system. If the workshop is in the middle of an existing building, you can’t pump out the air very well.

‘You also have to factor in how fresh air will enter the space to make up for what you’ve extracted. In an industrial unit, you might have roller-shutter doors leading straight outside and fresh air can enter through those. But a room deep inside a building might be more blocked in. You think, “Oh, we’ll draw air from the corridors of the building,” but then you find it’s lined with fire doors that all have to be kept shut and there isn’t that airflow. We go through issues like that. They might be able to move somewhere else. Or I can advise them on different kinds of work to do, or in using different, safer materials that mean they can still use the space as intended.’

‘There are lots of things you can do,’ Neill concludes. ‘The main thing is to be aware it’s an issue in the first place.’ In

By Sotirios Papathanasiou

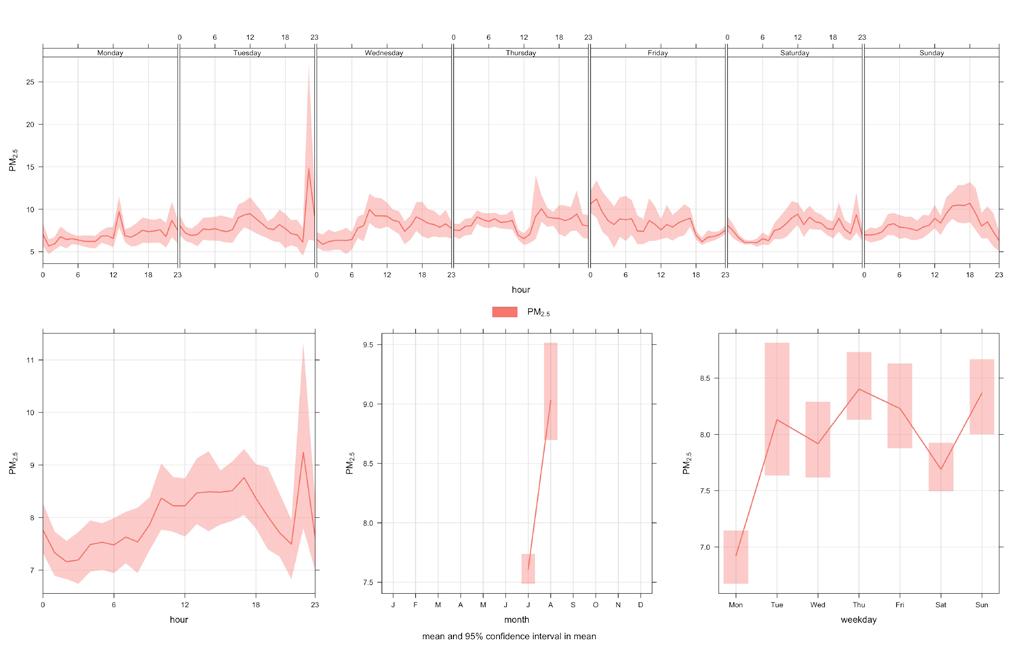

Earlier this year, air quality expert, campaigner and author, Sotirios Papathanasiou, asked himself this very question. On July 1 st, 2024 he began a unique experiment, tracking his personal air quality for a full year, carrying an Atmotube Pro and an AIRVALENT everywhere he goes.

Among things he’s hoping to discover is the effectiveness of personal air quality monitoring and the impact of daily activities such as cooking and traveling to work.

This article delves into the early findings of his experiment, examining the strengths and limitations of these affordable devices and offering insights into how they can be used to supplement traditional air quality monitoring methods.

A real-life experiment, using portable air quality monitors is essential to bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application. By carrying portable low-cost air quality monitors, we can gain invaluable insights into personal exposure to air pollutants across diverse environments. This data can help assess the effectiveness of existing protective measures, identify pollution hotspots, and evaluate the feasibility of individuals meeting WHO air quality guidelines in their daily lives. Ultimately, this experiment aims to empower people with knowledge about their air quality, enabling them to make informed decisions for their health and well-being.

However, several factors must be considered before relying solely on low-cost air quality monitors for personal protection. The accuracy and precision of low-cost sensors can vary significantly. Some may provide reliable data on specific pollutants, while others may be less accurate or sensitive. Additionally, the interpretation of sensor data can be complex, and users may not have the necessary knowledge to understand the implications of the readings.

To ensure that portable air quality monitors are effective in protecting individuals from air pollution, rigorous testing and evaluation are essential. This includes assessing the accuracy and precision of sensors under various environmental conditions, developing clear and understandable guidelines for interpreting

sensor data, and providing educational resources to help users make informed decisions.

For this experiment two portable air quality monitors, which have already been evaluated by many bodies will be used in combination to measure fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Among the multitude of air pollutants, these two parameters stand out as particularly crucial. Air quality has emerged as a critical concern, impacting our health, productivity, and overall well-being. To effectively address this issue, accurate and reliable monitoring is essential.

PM2.5: A Silent Threat

PM2.5, fine particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less, is a microscopic threat. Its insidious nature lies in its ability to penetrate deep into the lungs, causing a myriad of health problems from respiratory ailments to heart disease. Although PM2.5 provides a crucial indicator of air quality, it does not account for the size or shape of the particles. Despite these limitations, PM2.5 remains the most practical and widely adopted parameter in low-cost air quality monitors due to its strong correlation with adverse health effects and the availability of relatively inexpensive sensors capable of measuring it with reasonable accuracy.

What makes PM2.5 particularly challenging is its ubiquity. Both outdoor and indoor environments are susceptible to PM2.5 pollution, stemming from sources as diverse as vehicle exhaust, industrial emissions, cooking, cleaning, and even natural occurrences like wildfires. By monitoring PM2.5 levels, individuals and communities can gain valuable insights into the air they breathe and take proactive measures to protect their health.

CO2 offers a crucial perspective on indoor air quality. As a byproduct of human respiration and combustion, CO2 levels serve as a reliable proxy for ventilation effectiveness. When CO2 concentrations rise, it often signals poor air exchange and the potential accumulation of other harmful pollutants, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Monitoring CO2 levels empowers individuals to assess the quality of the air within their homes, offices, and other indoor spaces. By taking steps to improve ventilation and reduce CO2 buildup, people can create healthier and more productive environments.

When considered together, PM2.5 and CO2 provide a comprehensive assessment of air quality. PM2.5 highlights the external threats to our health, while CO2 sheds light on the conditions within our indoor environment. By tracking these parameters, individuals can make informed decisions about when and where to spend time, and take steps to mitigate exposure to harmful pollutants. Moreover, the data collected from PM2.5 and CO2 monitoring can be invaluable for researchers, policymakers, and public health officials. It can help identify pollution hotspots, track the effectiveness of mitigation strategies, and develop targeted interventions to improve air quality on both local and global scales.

Low-cost PM2.5 sensors are prone to interference from high humidity, which can significantly impact their accuracy. When relative humidity (RH) levels reach around 70%, these sensors often become unreliable. This limitation arises from the way these sensors function; they utilise laser scattering to detect particulate matter, and water droplets in the air can interfere with this process, leading to inaccurate PM2.5 readings. As a result, this study will exclude PM2.5 measurements when RH exceeds a certain threshold, to ensure data reliability and avoid drawing incorrect conclusions based on compromised sensor readings.

Low-cost PM sensors, particularly when measuring PM10, often struggle to accurately estimate larger particles due to various limitations. One significant issue is the inability to differentiate larger ones that are out of focus within the laser beam. This misclassification leads to an incorrect estimation of PM10 levels, as larger particles are incorrectly categorised as smaller ones. For this reason all PM10 measurements are excluded from this analysis.

Low-cost CO2 (NDIR) sensors, despite their affordability, often suffer from limitations that can impact their accuracy. These sensors typically rely on automatic calibration algorithms, which may not always be sufficient for precise measurements. Additionally, prolonged exposure to high CO2 concentrations can affect sensor performance, necessitating exposure to ambient air for recalibration. This requirement can introduce delays in data collection and potentially compromise the reliability of readings, especially in dynamic environments where CO2 levels fluctuate rapidly.

Meeting WHO Air Quality Guidelines

Another important question is whether carrying portable air quality monitors can contribute to meeting WHO air quality guidelines for PM2.5. While these devices can provide valuable data on personal exposure to air pollution, they do not necessarily represent the overall air quality in a given area. To effectively address air pollution at a population level, comprehensive monitoring networks and robust pollution control measures are required.

Nevertheless, portable air quality monitors could potentially play a role in supporting public health efforts. For example, data collected from these devices could be used to identify hotspots of air pollution, inform public health interventions, and engage citizens in air quality management. However, this potential benefit depends on the quality of the data collected and the ability to effectively integrate it into existing air quality monitoring systems.

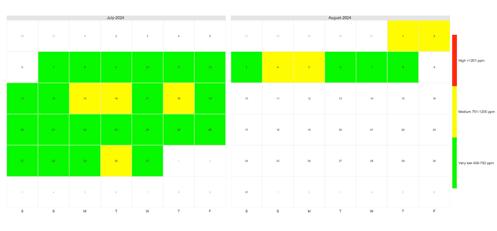

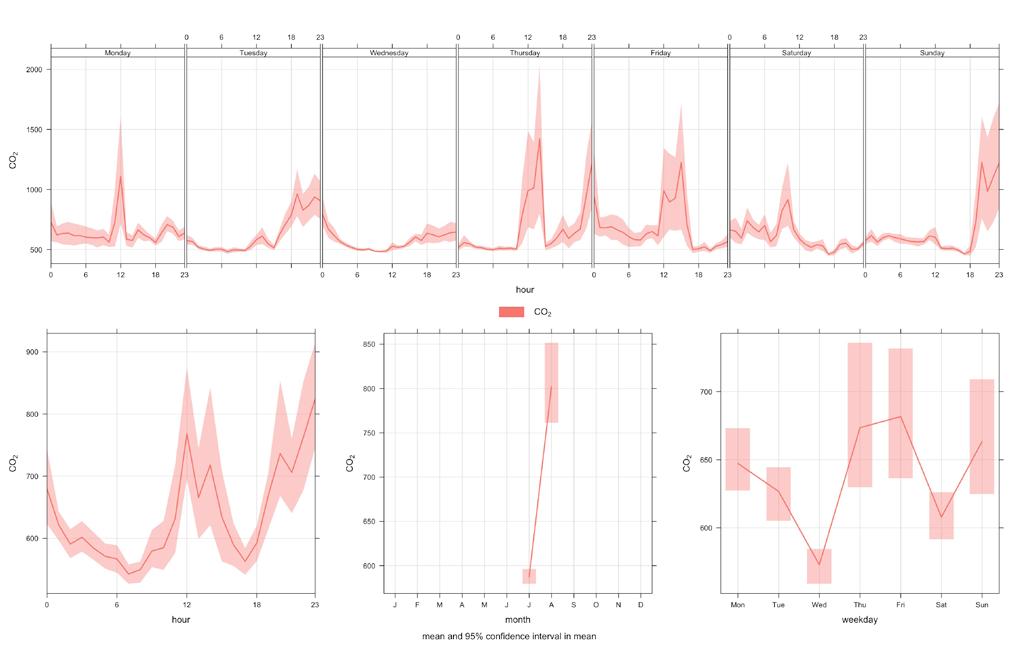

A preliminary month-long data analysis utilising low-cost air quality monitors to track individual exposure to PM2.5 and CO2 has unveiled significant challenges in avoiding high peak concentrations. The data indicates that individuals face difficulties in consistently mitigating exposure due to the dynamic nature of air quality and the complexities of real-time decision-making.

In detail, the analysis of the month-long air quality data reveals a complex picture. The PM2.5 Calendar graph indicates that daily exposure levels mostly remained below the WHO AQG 2021 limit of 15 µg/m³, with only a single day exceeding this threshold. While encouraging, the CO2 Calendar graph shows average exposure within acceptable ranges of 450-1200 ppm. However, a recurring concern is the presence of numerous spikes in

both PM2.5 and CO2 levels, suggesting intermittent exposure to significantly poorer air quality. These findings underscore the need for a more granular understanding of these peaks to identify potential sources and inform strategies for mitigating exposure to harmful pollutants.

The ability to continuously monitor personal exposure to air pollutants offers valuable insights into individual risk. However, our findings suggest that relying solely on user intervention to avoid harmful spikes is impractical. The rapid fluctuations in air quality, both indoors and outdoors, demand a level of constant vigilance and adjustment that is beyond the capacity of most individuals.

To effectively protect individuals from harmful air pollution exposure, there is a clear need for automated systems capable of controlling indoor environments and making real-time adjustments based on air quality data. Such systems could optimise ventilation, filtration, and other measures to minimise exposure to pollutants like PM2.5 and CO2.

As this study progresses, we anticipate gaining a deeper understanding of the patterns and factors influencing personal exposure to air pollutants. This knowledge will be instrumental in developing more effective strategies for protecting public health.

Sotirios Papathanasiou has written books exploring the complexities of air quality and its far-reaching consequences for both adults and children.

Want to buy his books? Scan the QR code or visit: www.amazon.co.uk/stores/ author/B06Y4FT3YV

By Päivi Aakko-Saksa, VTT

The PAREMPI project, funded by the EU, was set up to investigate the contribution of secondary aerosols, generated by all forms of transport, to the levels of ambient PM2.5 .

The PAREMPI project aims to thoroughly investigate exhaust emissions from the transport sector – not only the pollutants emitted directly from the tailpipe, but also the secondary aerosols (SecA) that form through atmospheric reactions.

Transportation is a vital part of modern life, enabling mobility and delivery of goods such as food, energy, and everyday essentials. However, there is a significant downside: these activities release a substantial amounts of greenhouse gases and air pollutants. We’re fighting the climate impact of transportation with electric vehicles, better energy efficiency, and carbon-neutral fuels, while tacking the exhaust emissions require also advanced exhaust aftertreatment systems (EATS). Yet, some transport sectors, like aviation and shipping, are difficult to electrify or equip with EATS. Additionally, current solutions focus mainly on tailpipe emissions, often ignoring how these emissions form secondary aerosols in the atmosphere.

That’s where the PAREMPI project steps in, investigating transport emissions, including secondary air pollutants and directly emitted species such as gases, semivolatile compounds (SVCs), ultrafine particles (UFPs), and particulate matter (PM), many of which are especially harmful to health, the environment, and the economy. Non-exhaust emissions are also on the radar.

There’s a significant knowledge gap in how transport emissions contribute to secondary aerosol formation, highlighting the need for more research and ways to curb these emissions. The PAREMPI project is building a comprehensive emissions database from existing results and new measurements, developing ePMI software to model total particulate emissions, and enhancing health impact assessments and societal cost analyses. All these efforts aim to provide solid policy recommendations from the PAREMPI consortium’s experts.

Particulate matter is a familiar component of aerosols, defined as “a mix of solid and liquid particles in the air that are small enough not to settle on the ground” (World Health Organization (WHO)). Secondary aerosols are formed when aerosol and gas-phase precursor compounds from both natural and human-made sources, including transportation, are released into the atmosphere, where they interact with water, oxygen, oxidants (hydroxyl radicals, ozone), and sunlight, leading to secondary aerosols through atmospheric reactions.

Aromatic compounds are known to significantly contribute to forming organic aerosols, while inorganic aerosols primarily consist of salts from, for instance, sulphur oxides (SOx), ammonia (NH3), and nitrogen oxide (NOx). Organic aerosols’ formation involves nucleation, the condensation of organic gases onto existing aerosol particles, or reactions of primary organic compounds into new molecules. The PM mass measured from the tailpipe is typically less than what’s found after these atmospheric reactions, contributing to the ambient levels of particulate matter with diameter smaller than 2.5 µm (PM2.5).

The formation of SecA through atmospheric reactions is complicated due to variations in exhaust composition, the compounds and their concentrations present in the atmosphere, and the prevailing atmospheric conditions. For instance, air quality typically worsens during low winter temperatures with low mixing height, but the exact reasons, especially in relation to transport emissions, aren’t well understood. Overall, proving the role of transport emissions in ambient PM2.5 levels and their harmful effects is a challenge.

To understand the impact of transport sectors’ tailpipe emissions on SecA, we need insights into SecA’s precursor emissions and tendency of those precursors to form SecA.

So far, the focus has been on basic emissions from transport activities, including SOx, total hydrocarbons (HC), PM, black carbon (BC) and NOx with less information on compounds like benzene, toluene, PAHs, UFPs, semivolatiles ((S)VOCs), NH3, and the mass, composition, and toxicity of formed SecA. Emission of these species vary depending on the engine, aftertreatment, and fuel technologies.

The PAREMPI project’s analysis of existing data revealed significant knowledge gaps, particularly regarding emissions under real-world conditions. The PAREMPI database, which includes 21 studies with OFR measurements of SecA from cars, heavy-duty vehicles, shipping, and aviation, showed that even for cars and HDVs, there’s limited data on emissions under real-driving (RDE) conditions. For shipping, available datasets are mainly for individual ships and typically cover only some emission species. Additionally, studies focus primarily on residual or distillate marine fuels that meet the IMO’s 0.5% sulfur limit (or 3.5% sulfur limit with scrubbers), while there’s little data on LNG DF, methanol DF, and biofuels, which are increasingly used to meet the IMO’s net-zero shipping goals by 2050. For aviation, there’s a general lack of SecA emission data, especially on sustainable aviation fuels (SAF).

PAREMPI’s measurement campaigns were designed based on the recognized gaps in emission data from transport sectors.

Of the four measurement campaigns, two are complete, focusing on cars and heavy-duty trucks, and the upcoming measurements will cover marine and aviation sectors. In the first campaign, seven cars representing hybrid, diesel, gasoline, and compressed natural gas (CNG) technologies were tested at the BOSMAL research institute in Poland, with over 30 participants from various project organizations. Most cars met the Euro 6d standards, but two older cars, one gasoline and one diesel, were not equipped with particulate filters. The laboratory test cycle simulated the RDE on-road profile, while different ambient temperatures in the chassis dynamometer lab reached as low as -9°C. For on-road car measurements, the Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) was used.

In the second campaign, focusing on heavy-duty vehicle emissions with two trucks reached as far north as Lapland, gathering data on HD emissions in cold and dark winter conditions, an aspect that’s not well understood. The campaign included a new diesel truck that met the latest Euro VI E emission standard and an older Euro VI diesel truck with over a million kilometers on its odometer. Conventional diesel fuel and an aromatic-free renewable diesel were used. In the on-road heavy-duty campaign, the measuring devices were installed in a measurement container on the truck’s semi-trailer. This setup allowed for real-driving on-road measurements with a large set of instruments in a container, though it required extensive design and logistics, and presented challenges, including switching the measurement container between the two trucks.

Both PAREMPI measurement campaigns included comprehensive measurements of precursor gaseous emissions (e.g., formaldehyde, aromatics), semivolatiles, and particle mass and number emissions down to <10 nm, as well as the toxicity of exhaust. Secondary aerosol emissions form during the atmospheric aging process, lasting from minutes to weeks, so SecA can’t be directly measured. In the PAREMPI measurements, potential SecA formation was assessed using an oxidation flow reactor (OFR), where high concentrations of oxidants (O3, OH, HO2) under UV light will initiate SecA formation. The aging of diluted exhaust in the OFR has been shown to represent atmospheric aging ranging from minutes to weeks, depending on the OFR conditions. After the OFR, PN concentrations, size distributions, and aerosol compositions are measured online using tools like the Soot Particle Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (SPAMS). The measurements with cars and trucks provide insights into emissions under various conditions, especially in cold and dark winter conditions, and the upcoming campaigns will focus on marine and aviation emissions.

Modelling and Health Impact Assessment are important tools to achieve the outcomes of the project. The PAREMPI database and the knowledge gained from the measurements will be used to model the reactions and processes leading to the formation of health-impacting SecA from precursor emissions due to atmospheric aerosol chemistry and to predict the total PM2.5. A modeling tool, known as the ePMI software, will be developed to assess the contribution of transport emissions to the formation of ambient PM With sufficient information on precursor gases, particles, and SecA emissions, combined with European-level modelling, health impact assessments and improved quantification of externalities become possible.

Not all aerosols are equally harmful, so many characteristics need to be considered, including their composition, mass, size, and number emissions. For instance, particles may carry harmful polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Aerosols affect health by entering the respiratory system, with the smallest particles even penetrating the bloodstream, making them particularly harmful despite their low mass. Generally, transport-derived particles are small (<1 µm), while other particles, like sea salt, geological dust, and biogenic particles, tend to be larger than PM2.5. Particle emissions from cars and vehicles are limited by European emission standards, which include the number of non-volatile particles (nvPN) with a diameter above 23 nm, a limit that will tighten to 10 nm in Euro 7. However, considering the health and climate effects, total particle emissions are significant alongside the non-volatile particles, and these are included in the health impact assessment of aerosols and related external costs evaluated in the PAREMPI project. Through its scientific findings, tools, and methodologies, the PAREMPI project aims to provide solid and well-justified policy recommendations.

The PAREMPI project brings together some of Europe’s esteemed research organizations, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, the Finnish Meteorological Institute and Tampere University from Finland, BOSMAL from Poland, IEM Institute of Experimental Medicine from Czech Republic, ONERA from France, ULUND from Sweden and Magellan Circle from Portugal. This project is supported by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement No 01096133.

By Albert Presto

How a team of researchers in Pittsburgh used mobile phone cameras - and a great deal of ingenuityto extract air quality information from filters provided by US embassies in Africa. This provided significant data for a continent in which air quality monitoring remains extremely limited.

Exposure to air pollution, particularly from fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is the dominant environmental health risk worldwide. Air pollution exposure is linked to up to 5.5 million deaths annually. The exposure risk is more critical in low- and middle- income countries for several reasons, including rapid urban development, the use of solid fuels for cooking and home heating, and the use of older vehicles that lack modern pollution controls.

Reducing air pollution exposures relies on evidence-based policies. These policies rely on measurements of air pollution levels with high precision and accuracy. Additionally, measurements need to be chemically specific so that policymakers can identify the most important sources of air pollution. However, research- and regulatory-grade air pollutant monitors are expensive. The high cost of air quality monitors makes it nearly impossible for many countries to regularly monitor pollutants, leaving policy makers unable to enact evidence-based policies to reduce exposure.

Air pollution monitoring is extremely limited in Africa. Overall, there is a lack of air pollution monitoring infrastructure in many African nations, though there has been some success in deploying low-cost air pollutant sensors in a few cities.

While these low-cost sensors provide valuable data on PM2.5 concentrations, they lack compositional information that can be used to understand emissions sources.

In an effort to better understand air quality across the globe, my lab at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania has been working with colleagues at CMU-Africa to develop low-cost methods to quantify PM2.5 composition. One approach that we have developed uses cellphone cameras to measure air pollution. Since cellphone cameras are ubiquitous, this approach has the ability to provide air pollution data at extremely low cost.

Our cellphone-based approach targets a component of PM2.5 called black carbon (BC). BC is the sooty black material that you might see coming out of the tailpipe of a diesel truck. Quantifying BC concentrations is important for several reasons. Knowing the fraction of PM2.5 that is BC can give a window into the contribution of combustion to local air pollution in a city. BC may also pose higher specific toxicity than PM2.5 overall, making it more harmful to public health than other types of PM2.5 . Lastly, BC is considered a “short term climate forcer” because of the way it absorbs light and consequently warms the atmosphere. For example BC deposited onto snow will cause that snow to melt faster.

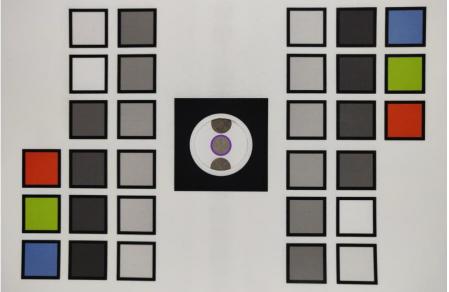

To determine black carbon concentrations, the filters are placed on a reference card and photographed. A photograph is composed of pixels, and each pixel is a combination of RGB channels. Having performed colour calibration of the original image - using the red, green and blue boxes - Albert’s team could determine the black carbon concentrations of a filter sample by extracting the averaged red channel of all pixels of the sampled area in the photo.

Our process is unique because it can be used to determine black carbon concentrations from a variety of different samples. All we need is a cellphone camera, a custom-designed reference card, and particles captured onto a filter. In a recent study, we worked with U.S. embassies to apply our method in multiple African cities. U.S. Embassies around the world collect air quality data using an instrument called a Beta Attenuation Monitor (BAM). The BAM uses a filter tape, and collects particle deposits onto the tape. These tapes were then sent to our team for analysis. After photographing the BAM tape on top of the reference card, we can apply an image processing algorithm to each photo to extract the red scale value of the photo. This value lets us identify the black carbon concentration during the hour of the day the tape was collected. By extracting black carbon concentrations, we can determine which parts of the pollutant are coming from fossil fuels as opposed to biomass burning or wood smoke.

We collected BAM tapes from U.S. embassies in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Ethiopia and compared their particulate matter to that collected from a site in Pittsburgh. In general, the African locations were significantly more polluted than Pittsburgh and other locations in North America or Europe. BC concentrations in the African cities were 10-20 times higher than the concentrations in Pittsburgh. These higher concentrations suggest that combustion emissions contribute significantly to human health risks from air pollution in these locations.

This process is a new way to think about low-cost analysis because the tapes are already being collected, so the marginal cost for our analysis is near zero. This method can democratize air quality data because any number of research groups around the world can collect tapes from other embassies and do their own analysis for practically no cost.

Beyond working with the embassies, I believe it is important to work with stakeholders in each country, whether that be other academics or just interested local parties, who want to use the data to advocate for improved public policy.

Our findings underlined the need for more air quality monitoring in developing countries. The black carbon levels in the SubSaharan African countries were as much as four times higher than those collected in Pittsburgh. Our findings allow us to provide insight into seasonal differences (wet-dry or summer-winter) differences in BC levels and to determine diurnal trends. For example, we saw in Accra that black carbon peaked early in the morning, every day of the week. Knowing this, can help in identifying and mitigating isolated sources.

Additionally, with the growing work to monitor air quality from outer space, more ground data is needed to calibrate satellite performance. Using this method, we can likely grow the number of locations where we can compare the satellite to data on the ground, ultimately making more data available to more countries around the world.

While our work continues in Pittsburgh, my colleagues at CMUAfrica are active in a network called AfriqAir. The hybrid air quality monitoring network introduces low-cost sensors and reference-grade monitors across eleven African countries and trains people to gather and analyse the data.

I am confident that developing countries can make positive changes to reduce harm from PM2.5 more easily with low-cost ways to monitor air quality. My lab plans to keep working with embassies, and hopes to also find a way to extract the filters in a solvent to uncover what else PM2.5 is composed of throughout the day.

Albert Presto

Research Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and the Director of the Center for Atmospheric Particle Studies

A Beta Attenuation Monitor (BAM) collects particles on a filter tape at a fixed flow rate every hour and measures PM2.5 by quantifying attenuation through the particle deposits. Each spot on the filter rolls representing an hour of the day.

6TH NOVEMBER, PROSPERO HOUSE, LONDON

Join

Sarah Legge has run her own consultancy working with public and private sectors, and was previously Head of Air Quality at the Greater London Authority.

Christopher Hammond joined UK100 in 2021, since then the network has doubled and launched two new ambitious programmes.

Simon Birkett from Clear Air in London presents his mission to achieve full compliance with WHO guidelines throughout London.

Fiona Coull from Cross River Partnership will explain how CRP’s are supporting public, private and voluntary organisations to address challenges around air quality.

Diana Varaden from Imperial College London will discuss the WellHome study, in which air quality monitors were place in over 100 homes across West London.

Case-study presentation from John Galsworthy, Director for Climate and Transport, Hammersmith & Fulham Council.

However,

By Martin Guttridge-Hewitt

With gas burners firing all day and limited ventilation, chefs and food prep staff are exposed to a harmful mix of indoor pollutants. But as Martin Guttridge-Hewitt learns, times are changing.

This summer while most of the British media indulged in a snap election feeding frenzy another culinary event got underway.

Specifically, the UK launch of the Global CookSafe Coalition (GCC) at the world’s first zero waste certified restaurant, London’s Silo.

Having created the blueprint for kitchens without waste in 2014, when his Hackney eatery opened, Head Chef and Owner Douglas McMaster is now thinking about different environmental challenges facing the sector: energy and emissions. More so, he’s among a growing number of hospitality professionals who recognise this is about climate responsibilities and fuel use, but also staff health.

Founded in Australia in 2022, the GCC is an alliance whose members in OECD countries have committed to delivering universal access to safe and sustainable cooking in new kitchens by 2030, and existing kitchens by 2040. Worldwide targets gave a longer tail, at 2035 for new kitchens and 2045 for the remainder. To achieve this a number of measures will be necessary, including degassing appliances and switching to induction cooking.

‘The Coalition has members and partners. Members are civic society organisations, technical teams, academics, the people who are thinking about policy and conducting research. And those charged with implementing legislation,’ explains Tushar Nair, UK/ EU Campaign Manager at the Global CookSafe Coalition. ‘Then we have partners, which are property companies, primarily, but we are looking at expanding that scope a little bit to also include retailers

and manufacturers, possibly restaurant associations and owners.

The private sector that operates the infrastructure.

‘That’s a conscious decision we’ve taken, we’re very mindful about not becoming a platform for greenwashing, so we want to know people involved with us are able to implement real changes, step up, do the work, not just take credit for it,’ he continues. ‘We also have a third category, which began last year with local governments in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia, who reached out to us to help with some really ambitious decarbonisation targets and the phase-out of gas. Since then, the Victoria state government has also joined, and we are hoping to welcome the City of Westminster Council soon, too.’

Professional chefs make up the fourth arm of the organisation, ranging from Michelin-starred celebrities through to new starters and ‘mom and pop’ operations. These ‘super stars’, as Nair calls them, perform two crucial roles – legitimising alternatives to gas cooking, namely high-tech induction hobs, and depoliticising the debate around fossil fuels in the kitchen. ‘They’re the people who get to say: “look – we are just here to talk about whether or not you can cook the food you know and love effectively and efficiently, maybe even better, by making the switch.” They’re neutral professionals.

‘The broader issue we are concerned with is decarbonisation, buildings are the biggest emitters in the world, so we want to play our role in that. But a big part of the messaging has been

around health benefits,’ says Nair. ‘If you go back to our initial launch in Australia, we have a medical doctor there talking about public health aspects of moving away from gas. So, this has been part of what we do from the beginning.’

Nevertheless, the vast majority of GCC partners join because they also want to bring greenhouse gas output down. By comparison, few are here to prioritise indoor air quality within commercial kitchens, and even less will be aware of the immediate dangers to staff that come from having multiple burners blazing on full-heat for the duration of an afternoon lunch or evening dinner service. This is something the organisation is hoping to change with its campaign work.

‘Just by having gas ignited for, say, 12 hours a day, multiple hobs, there’s also the heat itself negatively impacting physical and mental health. Burns and injuries are more common. Then there’s the air pollution side of things,’ Nair says. ‘The topline problem is the increased asthma risk from working around gas… But you’re burning fossil fuels in an enclosed space, that’s the real issue. We all hope to achieve 100% efficiency from that burning process, but it is never 100%, or even close.

‘So there are all these emissions blowing around the kitchen, and oven hoods to extract gas aren’t always designed to precise specifications,’ he continues. ‘So, we know there are very high nitrogen oxides just because there’s oxidised air and a flame. You can’t control that. And there are also continuous benzene emissions – most [gas cooker] manufacturers would not readily agree, but a small amount of leakage is inevitable. Our own data suggests around 75% of emissions from a stove occur when it’s switched off.’

Investigations into indoor air quality in commercial kitchens are almost non-existent, but studies into what we breathe when cooking at home are alarming. According to Zehnder research, cooking an omelette, stir-fry, or grilled food can raise pollution levels to more than three times the average London roadside, including significant quantities of fine particular matter (PM2.5 ). A separate analysis by the American Chemical Society suggests a roast dinner produces more particulates than you’d find on Delhi’s streets.

The GCC is hoping to expand studies in the area, and Nair cites ‘a number of chefs’ who have offered to wear sensors while working to measure real-time levels of different gases. Early talks are also underway with PSE Health Energy in the US, a policy-informing health-science research company, in the hope of measuring the differences between the impact of gas and electric hobs on air quality.

‘What we’re doing with the Federal Government in Australia is finding a way to make sure that a lot of decarbonisation subsidies are being put together to cover retrofit kitchens. Already a couple of chefs have access to that fund and they’ve been able to subsidise their transition,’ Nair replies when we ask how the GCC helps commercial kitchens switch off gas. ‘If you’re going to be moving towards greener technology, the government needs to be stepping in to make that transition much easier.’

Examples of businesses that have made the move remain difficult to come by for now, then, but Grosvenor Property UK have already begun the process. One of Britain’s biggest property management companies, responsible for thousands of commercial addresses, while terms vary the company has responsibility for the renovation of around 300 commercial kitchens used by hospitality businesses

and has committed to a 90% reduction in emissions by 2040. Degassing is a priority, and now all new fit-outs and retrofits are being delivered gas-free to meet targets.

‘A real caveat is whether we have access to the power supply. I think a lot of hurdles we’ve had when wanting to de-gas a full unit including the cooking is the power available,’ says Eve Bellers, Sustainability Manager at Grosvenor. ‘In some situations, we’d have to put in a new substation or ask for more power from the grid. That’s one of the biggest challenges we come up against, so where possible it’s been transitioning heating first, then looking at kitchens.’

The approach has worked in so far as removing the 55 largest gas boilers from the estate has seen company-wide consumption fall by 40%. But the switch to induction hobs is going to be a slower process, with opinion divided over the technology, and whether it can cook dishes to the same standard as gas.

‘We’ve seen across the board a range of responses. I think the small minority are those who completely bought into the idea and wanted to switch to electric, and those who, in contrast, wouldn’t even look at a gas free kitchen,’ says Bellers. ‘So, I don’t think we are there yet, within the market. But there’s another group who are coming to it and have never used gas-free cooking before, and this is their first step into it.

‘I think there is an ingrained reservation, a belief that gas gives better flavour, is more controllable. But we’ve noticed from those that have taken an all-electric unit, there are no examples that wanted to go back to gas,’ she continues. ‘A good example is a pub chain in one of our properties, this is their only gas free kitchen in the chain, and they think it’s faster, safer, more comfortable –all these benefits. But then we have had some who walked away from a unit because they realised it was gas free.’

The fact Grosvenor’s de-gassing policy isn’t going to change, despite a minority of potential clients pushing back, betrays the company’s confidence in the quality of its all-electric kitchens, and the need to transition. Like other GCC members, it has arrived at this decision from an emissions and energy standpoint. But in doing so, a co-benefit has been realised in reducing staff exposure to harmful gases and particulate matter, and this is rapidly rising up the agenda.

‘We know the big problems with gas are longer cooking times, increased temperatures in working environments, and basically being less comfortable places to cook. But we’re also aware of air pollution as a problem, and, in particular, particulate matter, which has now fed into our development approach,’ says Bellers. ‘We have created a sustainable development brief, which we give to tenants, and it has various layers to consider. One is now a ventilation strategy and indoor air quality plan. This lists out the pollutants than people should be aware of when designing a kitchen.’

For now, though, Grosvenor remains in the minority, both in terms of switching from gas in commercial kitchens and understanding the air quality argument for that move. But Nair and the GCC insist times are changing, and more professionals are waking up to the hidden risk of working in inadequately ventilated gas-filled spaces. Tipping this to a majority is still a way off and overcoming the research gap will be vital, but as evidence starts to mount it seems more organisations will inevitably make the switch to create a healthier, happier, and more efficient workplace.

Tim Dexter is the Clean Air Lead for Asthma + Lung UK which was formed in 2020 through the merger of Asthma UK and the British Lung Foundation. He overviews their campaigns, policy and influencing projects related to air pollution. Tim is currently focused on campaigns to influence national government policy, alongside regional campaigns in West Yorkshire, Greater Manchester and the West Midlands.

What is the state of play with lung health in the UK right now?

It’s not a pretty picture. At the moment, I believe we have the worst outcomes in terms of respiratory health of any country in Europe. We know there are there are many different factors to this, one of which being preventative issues such as smoking and air quality but it also comes down to aspects such as treatment. We know the pressure the NHS is under, but it’s difficult for people to able to get a diagnosis for their condition and to find the right treatment pathway and that is something that definitely needs to be prioritised.

And there’s the health inequalities around that. Respiratory health is a real issue, right across the country, but particularly within communities on the poorer end of the income spectrum. How has lung health improved in the UK compared to other diseases? Has it been slightly forgotten about? It feels that way. Respiratory illness is the third biggest killer in the UK, behind cancer and cardiovascular disease, but it receives a fraction of the research funding. And that’s one of the things that we, trying to raise money for research.

How much is air pollution a factor in lung disease?

It’s a huge contributing factor. We run regular surveys with our beneficiaries who say that they have a lung condition and when we do this, about 50% of people say that air pollution has a detrimental impact upon their condition.

This can be wide-ranging, from starting to feel a bit wheezy, feeling a bit breathless, noticing that’s it’s a bit more difficult when they’re walking along a busy road, to feeling like they’re trapped in their homes and can’t go outside, when the air quality affects them so deeply that they put themselves into a self-imposed lockdown. And obviously we know the wider impact that can have, on people’s physical and mental health from years of COVID.

Do you believe there is a greater awareness of the problems surrounding air pollution in general, and specifically among people who suffer from asthma and lung diseases?

I think there is some improvement in that but it’s still not anywhere where it needs to be. What we really need to see is a broader public health awareness campaign to really hammer this home. And we need to see it integrated within the direct advice and guidance that people receive from their clinicians and their GPS.

Once that connection is made, I think that’s when people will get the confidence to be able to connect it to what’s happened with their condition. And some people already do. Some people tell us that they’ve that lived in London all their life, they move out to a more rural area and all of a sudden it feels like a whole new lease of life, something they didn’t expect. The fact that they’re able to go outside, they’re able to enjoy time with their children.

But that’s not something we need to be advocating for. We don’t need everyone to move out to rural areas. We need the air quality to be better right across the country, and it shouldn’t be down to people to move house or put themselves in lockdown to be able to protect themselves from toxic air.

How much of Asthma + Lung UK’s work is directed towards air quality?

It’s one of our big missions, speaking to policy makers, trying to make sure that we see change at national, regional, local levels,

because this is an issue that you can take action on at every step of the policy ladder.

It’s also about raising awareness around air quality, integrating it into our health advice, what we tell people when they come to us asking for that guidance. We’ve also started to do some more proactive programs around this, such as a programme called Clean Air Champions in schools.

For the first year it was just in London, but we’ve rolled it out nationwide, working with hundreds of schools to help them monitor the air quality immediately outside the school gates to get a sense of what it’s what it’s like. We’ll use that to help raise awareness within the school and the wider community that’s connected to the school as well.

Last year you campaigned for a ‘transport plan for a greener, fairer future’. How much does a new government give you hope that things can change?

I felt like the last couple of years there’s been a kind of a stagnation in this issue, there’s been no real willingness to move it along. We’ve seen plans that were in place, such as in Greater Manchester, not come to fruition for clean air zones.

We saw unambitious targets introduced in the Clean Air Act, and which while it’s great to have those targets they aren’t really fit for purpose. I’ve got a two year-old and he’ll be 18 by the time those targets even come into effect.

The new Government have spoken a lot more positively around clean air, which has been great to see, and there was a possibility that we might see a Clean Air Act included within the manifesto and within the first King’s Speech so we were really disappointed not to see that.

But it’s great that we’re not getting the same kind of toxic conversation around clean air. We’re not talking about it in terms of a war on motorists. So there is more positive direction of travel in terms of that.

A lot of the initial successes are very much connected to other areas that we’re seeing progress in, such as improvements within public transport and active travel. But until we start to get a clearer picture of what the wider strategy and approach is, we’re obviously going to keep making sure that we’re holding their feet to the fire on this. Very much a metaphorical fire, given the subject matter.

You have focussed on transport a lot recently, is this likely to change?

Ultimately, this is such a nebulous area. You can go into so many different aspects of different policy portfolios, whether that’s agriculture, construction, transport, wood burning… but the reason we focused on transport, particularly for the last few years, is because we know it’s such a key source and we know what the solution is.

We know what getting polluting cars off the road does. We know what improving active travel opportunities does, what improving public transport can do. So, it feels like a no-brainer to go after that, and it feels like a no-brainer to implement those policy solutions as well. So that’s why we’ve really tried to focus that.

We’ll now start to look at this a bit more holistically as an issue, particularly if we feel that there’s a chance for new legislation to come in because obviously those overarching targets affect not just road transport, but absolutely everything.

Does Asthma + Lung UK have a position on LTNS ?

We don’t have a direct position on them. We get the sense that when they’re implemented correctly and with wider transport plans that they can show positive results. But we completely get that this isn’t necessarily always the case. Making sure that communities are being brought along is absolutely essential, because it’s impacting them in their day-to-day lives.

Asthma + Lung UK isn’t just about policy, is it, you deal with sufferers too?

Completely. One of the first things that we say we do is support people who have lung conditions. So, rather than just taking a top down overview of this, we have a helpline that operates 9:00 to 5:00 Monday to Friday. So people can call that up if they ever have concerns about their condition.

And we know that’s been really useful for when people feel like they might have met a bit of a dead end trying to get diagnosis or support, or if people have just found out for the first time that they have a condition and are not sure where to turn to or what to do with it.

It’s somewhere they can speak to a trained respiratory health professional to give them some advice, to offer follow up if needs be, offer opportunities for potential treatment pathways. And then we’ve also got a broader supportive care network that can also help with some of the more practical stuff, like how people can access financial support payments from the government, to try and make sure that some of that more dayto-day stuff is also taken care of?

That’s what we see ourselves as, first and foremost, how can we offer that health advice to people with lung conditions? But we do try and embed that within our campaigns as well, as I said, this isn’t just about us trying to speak for people and on behalf of people.

You were at the transport hustings in Greater Manchester a few months ago, where we got along several people from the region who have lung conditions to come and ask questions directly to the mayor.

It’s all very well and good for us to go along to a nice meeting in City Hall or Parliament and give them a bit of paper with some

stats on and we can have a good conversation about it but they’re only really going to understand the direct implications of what it is that we’re talking about when they hear from somebody who who’s like who lives there every day.

How is the treatment of asthma coming along?

It is progressing. There are other colleagues that would be able to speak better to this but there are some possible treatments in the pipeline that look positive. I think one of the big things, as ever, with this is just trying to make sure that people really understand what their medication is, what it should be and how they need to use it as well.

What is positive is that in the last few years, we’ve seen a little bit more of a broader awareness of asthma, particularly within schools. So schools now will have a policy about how they can support a child who has asthma, making sure that they have an inhaler and that they know how to use it and the staff are able to support. And that’s really important.

You recently hosted a photography exhibition called ‘This is Life and Breath’ can you tell us about that?

This is an answer to an issue that’s very real within the air quality campaigning world - how can we make the invisible visible? Because that’s one of the biggest challenges we get when trying to engage with people.

I’m sat here in Walthamstow, London and it doesn’t look like there’s any pollution. It certainly doesn’t look like what you’d see if you were to look up a stock image or pictures of the smog in the 1950s, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there and it doesn’t mean that it’s not an issue.