9 minute read

Reflections of a WWII POW

BATTLE OF THE BULGE CAPTIVITY

Reflections from a World War II prisoner of war

By Ruth Aresvik

VETERANS HELP NET CORRESPONDENT

Editor's Note: Army veteran and former POW Lt. Col. Joseph John Zelazny Jr. passed away on March 20, 2015. Parts of this story originally ran Dec. 16, 2014, in The Desert Sun (Palm Springs, Calif.) in an article, "Remembering the Battle of the Bulge on the 70th anniversary.”

It was early morning on Dec. 21, 1944, and U.S. Army 2nd Lt. Joe Zelazny was headed back to his battalion near the small town of Martelange, Belgium.

Just five days earlier, the Battle of the Bulge had begun when Germans launched a massive artillery attack against the Allied troops that stretched 80 miles across Belgium, Luxembourg and France.

Officer Zelazny and his driver had their Jeep loaded with radio equipment, a communications man, and a wounded lieutenant. They never made it back to camp.... "We ran into German paratroopers," Zelazny remembers.

The three men were captured while other American soldiers were gunned down on the spot. "A whole company right in front of us. They wiped them out. Then they put us up against a wall and shot us."

This came to be known as the Maelmedy Massacres. German soldiers shot American POWs and just left them in the snow to die.

Zelazny was shot in the left shoulder. The bullet had hit his clavicle and came out under his arm. "They let us lay there, thinking we were dead. Four hours later, a German officer turned us over and realized we were still living."

Two survived, one died. "They put us in a building, and we sat there watching them kill everybody."

Joe was sent to Stalag XII-A in Limburg, Germany. He received no medical care as a POW. He sat in a 6-foot-by-6-foot room for 10 days waiting to be interviewed. On the walls were the names of other men who had occupied the same space. Days later, Zelazny and other prisoners were transported by boxcars to Oflag 64 in Poland.

Lorrayne Zelazny, his new wife, was at work in Tacoma, Washington, when the telegram was delivered to her home. It was Jan. 8, 1945, on the one-year anniversary of their marriage.

Lorrayne asked her mother to read the telegram. Her mom opened the letter and said "...we'll bring it to you."

Lorrayne said she felt numb when her mom said, "Joe's missing." But also felt that he was OK, that he'd be back.

In February 1945, Zelazny and other prisoners were ordered out of the Poland camp. It was a horrid bitter winter with freezing temperatures. The men were weak with very little clothing. They were thankful to find dead horses along the way and ate raw horse meat.

After covering 230 miles in 28 days, Zelazny and another officer decided they'd had enough. They refused to go any further. They were taken by train to Stalag III-A, south of Berlin.

In early May, Russians liberated the camp and Zelazny and other officers walked 50 miles to the American lines. Joe weighed 190 pounds before his capture, 105 when he was liberated.

He sent two telegrams to his wife letting her know he was alive and coming home. He arrived before the telegrams reached her. "I called her on the phone, but she didn't believe it was me." • • •

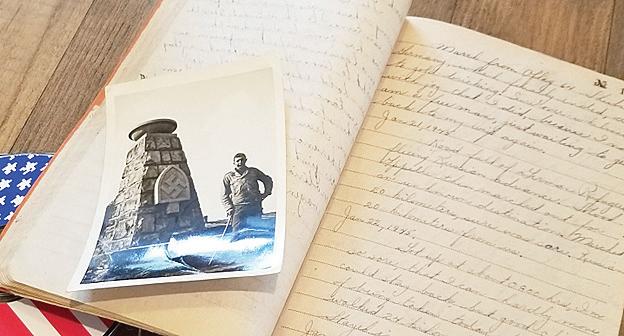

Fast forward 76 years as I sat with iced coffee at McDonald's with Joe's daughter Kathy Thomas. We pore over the newspaper clippings, photos, her father's journal...as she shares this amazing story. We talk about her dad's 21 years of service, retiring in 1963, and his devotion in working for veterans rights, establishing a Veterans Memorial at the Coachella Valley Cemetery (California) and one at the Tacoma War Memorial Park.

In 2009, he received the Meritorious Service Award from the National Association of Prisoners of War. Joe, along with other veterans, brought his story to local schools to educate and bring remembrance and honor.

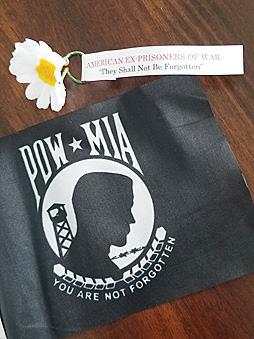

Kathy said that when her father passed away in 2015, she and her siblings found a bag of daisy lapel pins and attached ribbons with the tagline, "American Ex-Prisoners of War - They Shall Never Be Forgotten," and a handout with the following statement: "The daisy was chosen as a national symbol of all former POWs. The Military Code of Conduct required that only name, rank and serial number be divulged to the enemy. American folklore has long deemed that "daisies won't tell," making it a tribute to the memory of those who have endured the hardships of captivity in silence."

Kathy went on to say that in the early 1990s, her father's local POW Chapter passed out daisy lapel pins on the third Friday of September (National POW/ MIA Recognition Day) just as poppies are passed out on Veterans Day. "In his honor, our family is resurrecting this grassroots initiative called the POW/MIA Daisy Campaign."

Last year, and again this year, family and friends will place small U.S. flags adorned with a daisy on POW graves at Washington State Veterans Cemetery in Medical Lake; the same will be done on 227 POW graves at the National Veterans Cemetery in Kent, Washington.

We remember and honor the commitment and sacrifices made by this nation's prisoners of war and those who are still missing in action, as well as their families. Americans must remember its responsibility to stand behind those who served, and continue to serve, and make sure that we do all that is possible to account for those who have not returned.

Photos of Joe Zelazny in Germany, October 1944. Joe found hope

In his own words, and a winning entry from a “most memorable Christmas” competition of Tacoma’s The News Tribune (circa 1960), Joe Zelazny wrote: “The Christmas of 1944, I was a wounded POW sitting in a railroad station at Limburg, Germany, with numerous other American POWs. We were awaiting the arrival of a troop train to take us to Stalag XII-A for solitary confinement. The activity was rush-rush and it was disheartening to realize what we had to look forward to. At approximately 0300 hours on Christmas Day, a train full of wounded German soldiers arrived and unloaded. While we were together in the station, all of the wounded personnel, regardless of country and status, started singing Christmas carols - the first one was “Silent Night,” then “Joy to the World.” It was a touching moment.

Here we were, POWs who were supposed to be enemies, many of us suffering pain. Yet everyone had the Christmas spirit and sang these wonderful songs together. Every Christmas season since then, whenever I hear the first singing of “Silent Night,” I think back to that ‘most memorable’ Christmas Day of 1944. I thank God I am still alive. I am sure that if it weren’t for Christmas Day 1944, and the Christmas spirit, I might not have made it back as one of the few survivors of the Maelmedy Massacres.”

LEARNING ABOUT THE POW/MIA FLAG

STRONG SYMBOL REMEMBERS THOSE WHO REMAIN BEHIND

In 1971, Mrs. Michael Hoff, the wife of a U.S. military officer listed as missing in action during the Vietnam War, developed the idea for a national flag to remind every American of the U.S. service members whose fates were never accounted for during the war.

Mrs. Hoff went to the Annis Flag Company, who assigned the task to its advertising agency in New Jersey.

Newt Heisley, a former World War II veteran pilot and creative director at the agency, was honored and inspired when the design of the flag emblem became his project. The flag depicts a black and white image of a gaunt silhouette, a strand of barbed wire and an ominous watchtower.

Some claim the silhouette is a profile of Heisley's son, who contracted hepatitis while training in Marine boot camp. The virus ravaged his body, leaving his features hollow and emaciated. Heisley saw the stark image of American service members held captive under harsh conditions.

By the end of the Vietnam War, more than 2,500 service members were listed by the Department of Defense as Prisoner of War (POW) or Missing in Action (MIA).

In 1979, as families of the missing pressed for full accountability, Congress and the President proclaimed the first National POW/MIA Recognition Day (the third Friday of September) to acknowledge the families' concerns and symbolize the steadfast resolve of the American people to never forget the men and women who gave up their freedom protecting ours.

Three years later, in 1982, the POW/ MIA flag became the only flag other than the Stars and Stripes to fly over the White House in Washington, D.C.

On Aug. 10, 1980, Congress passed U.S. Public Law 101-355 designating the POW/MIA flag: "The symbol of our Nation's concern and commitment to resolving as fully as possible the fates of American still prisoner, missing and unaccounted for in Southeast Asia."

SOURCE: www.va.gov/opa/ publications/celebrate/powmia

‘Honor the Dead – Serve the Living’

Missing Man Table remembers POW/MIAs

The Missing Man Table, also known as the fallen comrade table, is steeped in symbolism and is featured in solemn ceremonies, such as National POW/MIA Recognition Day, for fallen, missing or imprisoned U.S. military service members.

Each item on the Missing Man Table represents the emotions and feelings reserved for those who did not come home. The ceremony symbolizes that they are with us, here in spirit. All Americans should never forget the brave men and women who answered our nation's call to serve and fought for our freedom with honor.

The table is round, to show our everlasting concern for our missing men.

The cloth is white, symbolizing the purity of their motives when answering the call to serve.

The single rose, displayed in a vase, reminds us of the blood they may have shed in sacrifice to ensure our freedom, and of their loved ones and friends who keep the faith while awaiting their return.

The red ribbon symbolizes our continued determination to account for our missing.

A slice of lemon reminds us of their bitter fate; captured and missing in a foreign land.

A pinch of salt symbolizes the tears of our missing and their families who long for answers after decades of uncertainty.

The lighted candle reflects our hope for their return, alive or dead.

The Bible represents the strength gained through faith to sustain us and those lost from our country, founded as one nation under God.

The glass is inverted - they cannot toast with us at this time.

The chair is empty - they are not here. SOURCE: www. warmemorial center.org