29 minute read

Pariprasna

Q & A with Srimat Swami Tapasyananda (1904 to 1991), Vice-President of the Ramakrishna Order.

Approach the wise sages, offer reverential salutations, repeatedly ask proper questions, serve them and thus know the Truth. — Bhagavad Gita

Advertisement

Question: “Relinquishing all Dharma, take shelter in Me. I shall liberate you from all sin,” says the Lord in the Gita. What do Dharma and ‘seeking shelter’ mean here? Maharaj: As this verse occurs at the end of the Gita, it is taken to summarize the teaching of the Scripture and is therefore of great importance. So different Acharyas have interpreted it differently in the light of and in agreement with, the philosophies they uphold. We shall therefore give here the interpretation given by a few of them. Sankara says Dharma here includes also its opposite Adharma and interprets the word to mean ‘Karma or all actions bringing merit or demerit’. And ‘seeking shelter’ means realizing oneness with Him who is the soul of all, who is equally everywhere, who is indwelling everything, who is Lord of all and who is undecaying and beyond the pale of birth, death, etc. In other words, on realizing that there is none other than He, a person is liberated by the unitary consciousness from the bondage of sin i.e., of Dharma and Adharma. According to Sankara the last stage of spiritual life consists in abandoning every form of action, whatever be its nature and seeking union with the Supreme Being. In the light of this philosophy, all actions are prompted by the ego and, so long as the ego is present, oneness cannot be realized. Continuance of actions which are born of egotistic impulse will only help to emphasize the ego and will obstruct the discipline of reflection for its effacement. Hence work of every description, whether moral or immoral or of an indifferent nature from the worldly standpoint, have to be abandoned in the last stage and the effacement of the ego sought through union with the Supreme recognized through reflection. But it must be carefully noted that the abandonment of work is not the practice of idleness but the spontaneous falling away of actions as the ego-sense is attenuated through reflection. Ramanuja takes Dharma in a pure devotional sense and gives it two meanings: 1. Abandonment of all Dharma means the abandonment not of actions but of all the ‘fruits of, and the sense of agency involved in, the practice of the disciplines of Karma Yoga, Jnana Yoga and Bhakti Yoga’; and ‘seeking shelter’ in the Lord means ‘recognizing simultaneously that one’s sole support and refuge consists not in any of these disciplines, but in the Supreme Being, the only ultimate agent and object to be worshipped.’ In regard to a true devotee the Lord promises that He will destroy all obstructions and obstacles in the way of the attainment of devotion, resulting from the sinful tendencies and the sins of omission and commission accumulated through several births. 2. A second meaning given by Ramanuja is this: The obstruction in the way of the generation and growth of devotion consists in the sins and sinful tendencies accumulated in many past births. For freeing oneself from the effects of these sins of omission and commission there are many expiatory ascetic practices prescribed, like Krichra,

Chandrayana, Vaiswanara, Prajapatya etc. These practices are innumerable and are rather difficult to accomplish and life on earth is too short for one to take to all these practices. Realizing this, one should abandon all these Dharmas (expiatory prescriptions of the scripture), and depend on the Lord, who is supremely merciful, who is

possessed of countless attributes, who is the sole refuge of all the worlds and who is all love and benevolence to those who seek shelter in Him, for the removal of the obstructing sins and the setting of the favourable situation needed for the practice of devotion. In other words, not any human effort, but sole dependence on the mercy of the Lord, can help us in overcoming sins and obstacles in the spiritual path and bringing the flower of Bhakti into blossom. Vallabha, another great authority on Bhakti and the founder of the Pushti Marga, says that Dharmas which are required to be abandoned here include all ways of life and thought that stand in the way of complete self-surrender to the Lord and adds that the performance of things conducive to that self-surrender (like thinking of Him, doing work without expecting the fruits, and beholding agency in Him etc) is not to be abandoned. But he would prefer to interpret the idea as the discarding of all Dharmas characterized by allegiance to, and dependence on, aids and agencies other than the grace of God. A person who makes such a discarding becomes an Akinchana (one without the support of anything other than the grace of the Lord, without even the support of the strength of one’s spiritual practices) and an Ananya (serving or owing allegiance to no being other than God). Nimbarka interprets Dharma thus: abandoning all Dharmas i.e., the Varnashrama Dharmas (the duties enjoined by scriptures and society) and also Dehadharmas (the pursuit of pleasures and avoidance of pain and other similar bodily pursuits) one should seek God and God alone until one is absorbed in Nirvikalpa Samadhi. Sridhara, another great commentator who is both an Advaitin and an adherent of the devotional school, interprets Dharma as follows: Dharmas are Vedic injunctions or commandments in regard to man’s duties. One who follows these injunctions strictly is considered to be living a life of Dharma. Giving up such a life which is only a life of slavery to injunctions and, convinced that all good will come through devotion to God, one should take refuge in Him alone and not in Vedic injunctions. There need be no fear that thereby one will be abjuring one’s duties. For the man whose sole refuge is the Lord is assured that he is liberated from all sins of omission. It will thus be seen that the word Dharma here in the Gita is a hurdle for all commentators. The word Dharma, if taken in its usual sense of ‘morality’, ‘duty’ etc., will lead to many difficulties. Abjuring morality or duty cannot be considered to be a part of spiritual life. So the word Dharma has been given technical meanings from the points of view of particular philosophies. Ramanuja’s interpretation is probably the most convincing to an uncommitted mind. To put it in simple language, it means that while observing all Dharmas or moral and spiritual disciplines, we have to know that they are in themselves not sufficient to remove sins and accumulated obstacles in the way of spiritual realization. None the less, these disciplines have to be undertaken, without any sense of agency or attachment to results. For the person treading the spiritual path should know that God alone is the ultimate agent, as all powers of work are ultimately from Him. So the fruits of all devotional works too have to be surrendered to Him. The abandonment required of the aspirant is the abandonment of fruits and the sense of agency of the Sadhana performed. While practising this outlook, the Sadhaka should not be at all lethargic or indifferent to the meticulous performance of spiritual disciplines. He should practise them sedulously but at the same time depend not on the practices, but solely on God’s grace for the removal of all obstacles on the path of spiritual realization and for the dawn of pure Bhakti of the highest order, which is the most luscious fruit of spiritual life. This is ‘seeking shelter’ or refuge in God. This seems to be in keeping with the main purport of the Gita too. Selections from Spiritual Quest: Questions & Answers by Swami Tapasyananda

When Indians Meet… An Encounter with the Native America as part of an engagement with the Parliament of World Religions

RAMASUBRAMANIAN

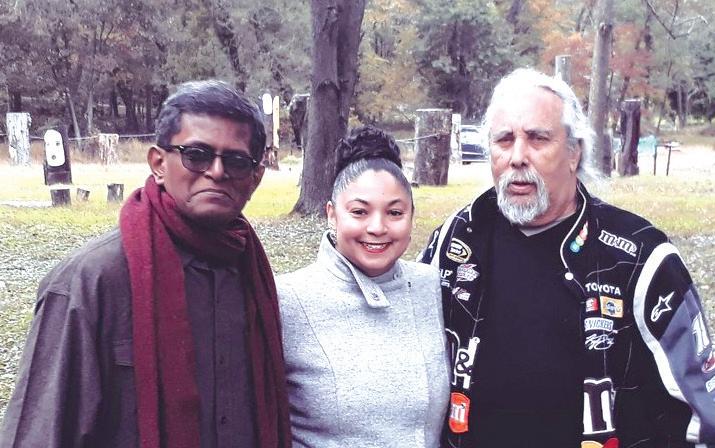

With the blessings of Sri Ramakrishna, Sri Sarada Devi, and Swami Vivekananda, and the sannyasis of the Ramakrishna Order, I had the good fortune of attending the Parliament of World Religions in Toronto in Nov 2017. Before reaching Toronto, I was on a 2-week visit to the USA where I spent time delivering a few lectures and interacting with Indigenous American leaders and thinkers for a dialogue that I call the ‘Indian – Indian Dialogue’. I was trying to understand their world view, current situation, their struggles and how they see the world in the context of today’s climate change and global warming crisis. In this article, I summarize some of the salient aspects of the dialogue with these Native Americans.

This article is informed by my dialogues with native leaders, my own research, and my extensive conversations with my colleague and host, Reverend. Sara Jolena Wolcott, Director of Sequoia Samanvaya, who is one of the Americans actively engaging in changing the way Americans see their history.

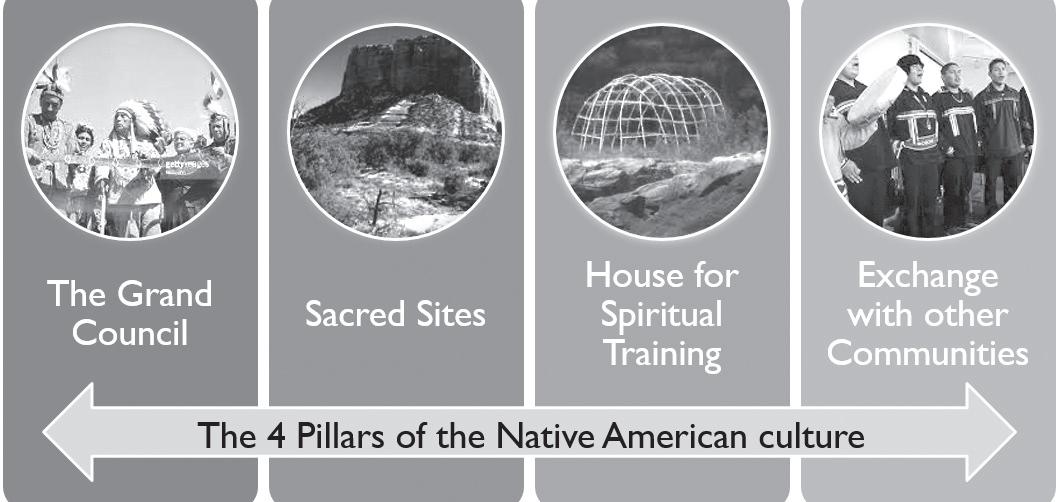

America has been a great country and presents itself today in a glorious manner and has become the aspiration for hard-working people throughout the world. The entire world has been impacted by American commerce, thinking, culture, language and its way of living and working. Yet what is this dream, the ‘American Way of Life’, really built on? The American dream story is incomplete without the mention of the original inhabitants of the land, the Native Americans as they are called, or the Indigenous people or American Indians as they are more frequently called, or just Indians within America (they are called increasingly people of the ‘First Nation’, particularly in Canada). Growing up in India, for me the Native American story is limited to the few images of ‘Red Indians’ that were copied from movies of the west in India and a few other comic strips. The little that I got to read about the wisdom of the Native American people, as a young person and much more later with the advent of the search engine, wanted me to understand them more. I find, under the surface of false histories and deep historical wounds, America is also a land of spiritual wealth and a deeply generous, open hearted indigenous peoples who are still offering their wisdom, the possibility of sustainable lifestyles, and their hospitality to visitors, immigrants, and settlers. It seemed to me that there is much in resonance in their culture to our own. It also occurred to me that we in India never get to read the real story of the Native Americans, their encounters with the Europeans, their repeated suppression, near annihilation, slavery, current situation, their challenge as citizens of the new American State, their land, sacred sites, wisdom, knowledge, livelihood, or lifestyle.

I as an Indian aware of the spiritual traditions of our land, wanted to experience and understand the American land from the Native American view point. Meeting several of the Native American leaders, discussing larger challenges today, whether it be continued s t a t u s o f n e gl e c t , s u p p re s s i o n a n d marginalization in their society or their deep pride and wisdom about their past and spiritual tradition, it was an insightful learning experience. That is what I outline in the rest of the article here. During the famous Parliament of World Religions in 1893 when Swami Vivekananda’s universal inclusive message of harmony of religions gained global attention, it is said that there were no Native Americans present or invited to speak: ‘… despite sentiments of universal fellowship expressed at the Parliament, there were no Native Americans present except in the curiosities display of American Indians on the fair’s midway. For many visitors, these Indians were as exotic as Vivekananda. But no native elder or chief was invited to speak at the Parliament. Native American lifeways were not yet seen as a spiritual perspective. Just three years earlier Chief Sitting Bull had been arrested and killed, the Ghost Dance had been suppressed, and 350 Sioux had been massacred at Wounded Knee Creek.’ 1

What was not discussed in 1893 was the extent to which the Christian colonial legacy of America remained an unquestioned ethos of the land. To understand this, we need to perhaps go back another 400 years in history to the time when the Christian project of ‘enlightening the world’ set sail from Europe with the singular mission of conquering all lands that were not ruled by Christians and converting all ‘heathens’ to Christians. Columbus was one such who set sail westward in search of India with a faulty understanding of the global navigation. 2 He came from a family of slave-traders and entered what we now call the Carribean (he never set foot on the American mainland) with a worldview that saw darker skinned people as inferior to Christian Europeans. Upon his return to Europe, Spain and Portugal sought to gain wealth from land they did not know existed. The Pope of the time agreed, writing a decree, known as a Papal Bull, which voyage ‘intended to seek out and discover certain remote and unknown lands, to the end that you might bring to the worship of our Redeemer and the Catholic faith their inhabitants… By the authority of Almighty God and of the new land that has been discovered shall belong to you and your heirs. Furthermore, under penalty of excommunication, we strictly forbid anyone else to visit these lands

for the purpose of trade (or for any reason) without your consent. Should anyone attempt this, be it known to him that he will incur the wrath of almighty God.’ 3 Columbus himself is supposed to have said this about the natives, ‘They should be good and intelligent servants, for I see that they say very quickly everything that is said to them; and I believe that they would become Christians very easily,….’ 4 . The Papal Bull, became a key document in what is now referred to as the Doctrine of Discovery. This doctrine has a sway over the American land even today. As the noted elder, Betty Lyons stated in a recent article, ‘the Doctrine of Discovery,…granting European nations sovereignty over non-Christian lands “discovered” by their explorers …continues to provide the legal underpinning of the denial of land rights to our peoples.’ 5 This vast American land that Columbus ‘discovered’ was inhabited by deeply spiritual

Native American Prayer Site, outside New Jersey

communities. They revered their land as sacred, worshipped the spirits of the land, paid homage to their ancestors and had several rituals and customs associated with all of this. They had nations or regions (map) inhabited by different tribes that were demarcated and where the tribes and their customs ruled. The area had been a homeland to numerous groups of Native Americans with their own thriving societies and history. For thousands of years, these peoples had managed to maintain their unique culture and lifestyle and to make their living. New Jersey airport, where I landed was the land of the Lenape people. ‘The arrival of the Europeans meant a drastic change for the Native Americans. Together with diseases which decimated the native population, the English settlers also brought an alien culture and religion. 6 As Betty Lyons puts it, ‘We know that supposed discovery of the so-called New World has had

Author with Mindahi Bastida Munoz

Chief Phil Lane Jr.

Chief Stacey Laform

its greatest negative impact on the tens of millions of indigenous peoples who lived here.’ The invaders looked at most of the landscape as ‘commodified’ products that could be shipped back to Europe. Historian, Cronon cites the way the ecology of the land was viewed by the colonizers in the New England area thus, ‘Visitors inevitably observed and recorded greatest numbers of “commodities” than other things which had not been labelled this way.’ 7 Obviously, the worldviews of the English and Native Americans differed significantly. The resulting conflict is sustained till today; this was echoed by Chief Perry, one of the Native American leaders I met in the Lenape land outside New Jersey. ‘Rich people everywhere are afraid of the spiritual people; we show the truth you see’, he said sharing the story of struggle to sustain their sacred prayer site with country houses expansion for millionaires all around that threatens him and his tribe from accessing their land. As we walked with him in the ground just outside New Jersey, it was interesting to observe a large new Hindu temple just a few hundred meters away. The contrast in the world view comes out stronger even today. One such was the introduction by Chief Hawk Storm, from the Schaghticoke First Nations, ‘I am water, I come from a tribe in which we consider ourselves water, today we are all polluted, as the water around us are polluted, so do we consider ourselves polluted.’ This sentiment deeply resonates with the sentiments expressed by Swami Swanand a.k.a. Prof. G.D. Agarwal, the environmental scientist, teacher and philosopher who gave up his body protesting against the unsustainable building of dams across the Ganga in India. It was only a few days after the passing away of Swami Swanand that I spoke to Chief Hawk and to witness the same concern and wisdom stemming from an ancient culture from the other end of the world was not merely fascinating, but, also reassuring. As we proceeded to discuss the current concerns of humanity as a whole, he made another statement that highlighted the wisdom of the Native people: ‘When we are ill, the body rejects the disease and so does the planet; today we humans are the illness of the planet.’ 8 Moving back in time, the vast differences in the world view also resonated in other areas of life. The Natives not only had an active production and commerce, they also had systems of governance and methods to resolve conflicts coming from their wisdom and respect for the land. A few hours north of where I landed in the Lenape land is situated the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee land (northern New York). It is here that five Native American nations came together. They taught the US government how to be democratic. ‘The Gayaneshakgowa, The Iroquois Great Law of Peace, is… the earliest surviving governmental tradition … based on the principle of peace; it was a system that provided for peaceful succession of leadership; it served as a kind of early United Nations; and it installed in

Chief Hawk Storm

Chief Aline La Flamme (centre)

Romano & Chief Perry (right corner)

government the idea of accountability to future life and responsibility to the seventh generation to come.... All of these ideas were present prior to the arrival of the white man.’ 9 Among the several stories regarding the peaceful aspiration of the people is the story of the Peacemaker and the Kanien’keha:ka. One of the Native American leaders narrates the same as follows – ‘Centuries ago a Natural World people gathered together at the head of a lake in the center of North America’s then virgin forest, and, there they counselled. The principles that emerged are unequalled in any political document that has yet emerged. They evolved a law that recognized that vertical hierarchy creates conflicts, and they dedicated the superbly complex organization of their society to function to prevent the rise internally of hierarchy. They established laws around hunting and fishing that eased conflicts and ensured freedom and a right to protection for anyone entering the country of the Haudenosaunee, under what the peacemaker called the “Great Tree of Peace” which was a white Pine tree.’ 10 Coming from southern India, I was struck by the similarity of justice being provided under a tree; in many of our villages it is the pipal tree. The sacredness of the tree provided the authority to the decisions, and also bound the community to protecting and living with the natural order. However, these nuances of understanding and living with the Natural order was lost on the new arrivals from Europe. While there are several narratives of the first encounter from the Colonizers point of view, how did the natives see the Colonizers? What did they perceive to be the motives and the intentions of the new arrivals? Unfortunately, only a few narratives are available from the Native American point of view and these are only oral traditions; but, some imageries that are perhaps passed on through oral tradition, presented by one of the authors illustrates the nature of the first encounters: ‘On the coast…Native hunters find that several of the traps that they had set are missing…in the place where these items had been is smoothly polished upright timber crossed near the top by a second piece of wood, from which hangs the carved effigy of a bleeding man. …In the Indian dwelling, a women tells her granddaughter about the first meeting between the Natives and Europeans. One day, she says, a floating island appeared on the horizon. The beings who inhabited it offered the Indians blocks of wood to eat and cups of human blood to drink. The first gift the people found tasteless and useless; the second appallingly vile. Unable to figure out who the visitors were, the Native people called them ouemichtigouchiou, or woodworkers.’ 11

‘Between 1492, when the Taino people first encountered Columbus, and 1620, when the Algonquin-speaking people first met the Pilgrims of the Mayflower, and which is where the United States tends to originate its own history, were 128 years. Much had happened during this time; as Sara Wolcott summarises, it is during this time that, (i) The Spanish entered present-day New Mexico (1540), Texas and South Carolina (that settlement was overthrown by the black slave rebellion). Natives continually worked to oust the Spanish, cumulating in the successful 1680 Pueblo rebellion in Santa Fe, (ii) the Dutch landed along Hudson River (1609/1615), where they met several native nations, including the Lenape; New Amsterdam was established in 1625 by Dutch West India Company on Manhattana, later re-named Manhattan, (iii) Small Pox wiped out a significant portion of the population; by the time the Mayflower landed in Plymouth, entire villages had been decimated. This significantly influenced the early relationships between indigenous peoples and Pilgrims.’ 12

Symbols of the Native American tribals were either usurped or slowly changed with the influence of the culture. ‘From the 1500s to the early 19 th century, the idealized image of ‘America’ was transformed from a dark-skinned, full bodied woman wearing a feathered headdress and a skirt of feathers or tobacco leaves, the symbol of fecundity, to a (white) Greek goddess.’ 13 Unlike the European arrival in India, where the initial purpose was seeking trade relations and the colonization project began much later, in the American land the purpose from the beginning was conversion to Christianity and rule over the Natives. Hence any resistance was put down violently. While estimates vary, several sources indicate that as high as 50 million Native Americans were intentionally killed by the invading Europeans between the 16 th and 17 th century. 14 Indeed, when one looks at the values celebrated by Modern America and what the modern Americans think they represent in the world, one can resonate with the question raised by one of the Native American writers, ‘North America had its own genocide against the First People – violent, devastating, effective. It was driven by a sense of racial and religious superiority, and the prize was land and resources. How could it be that the people so dedicated to democracy and freedom could have been so cruel to another people? What attitudes, beliefs, myths and misunderstandings give rise to and fuel this kind of conduct?’ 15 Official records today place the number of different tribes across the American nation of today as 573. This is independent of the tribes from the Mexican region or Canada. 16 The Native Americans today constitute about 5 million people across the continent, they are dispersed all over the region starting from Canada in the north all the way to Mexico in the south. They inhabit smaller patches of what

Transformation of Indian Boy

once was their own land. Many of them have the copies of the documents that were signed by the Europeans and keep reminding that their land has been illegally (according to their laws) taken over. One study places the amount of land taken over between 1887 to 1934 at about 90 million acres. Many of them have multiple citizenships today as the US law permits them to have citizenship of their tribal nation apart from that of the USA. The Nation of United States of America as it stands today was fundamentally land leased from the Native Americans through treaties. Today 374 such treaties govern the nation of USA. 17 Much of these treaties have never been re s p e c te d by s u b s e q u e n t A m e r i c a n governments and land was secured violently and retained by the governments. The Native Americans were restricted to ‘reserves’ set-up exclusively as captive spaces for them, while their sacred spaces were violated completely. For five consecutive generations, from roughly 1880-1980, Native American children in the United States and Canada were forcibly taken from their families and relocated to residential schools. In these schools, they were ‘educated’ and ‘civilized’ so that they no longer dress, behave or remember the culture of the Native American tribes and instead adopt the European lifestyle. The stated goal of this government program was to ‘kill the Indian to save the man.’ Half of the children did not

survive the experience, and those who did were left permanently scarred. The resulting alcoholism, suicide, and the transmission of trauma to their own children has led to a social disintegration with results that can only be described as genocidal. 18 Alluding to the educating of their children and the shift in their mind-sets subsequently, Chief Perry summarized the plight of the youth in the community when he said, ‘Our children could narrate the history of 10 generations; then they were forced into school and today they don’t know anything about their past.’ 19 Indeed, the modern American holidays such as ‘Thanksgiving’ and ‘Columbus Day’ are being increasingly opposed by people who are aware of its historical background; they want it to be commemorated as day of mourning and day of Indigenous people respectively. Today about 90 cities across the United States have already declared the Columbus Day as Indigenous People’s Day. One of my first engagements was with Mr. Mindahi Bastida, Director of the Original Caretakers Programme and also Director for the Centre of Earth Ethics in Union Theology College, New York. Hailing from the indigenous community in Mexico, Mr. Mindahi, after a brief ceremony to sanctify the meeting of ourtwo civilizations, invoked the holy spirits of his civilization through the blowing of the sacred flute (whistle) and invoking the ancestors of the two civilizations to guide the process of dialogue and engagement. He explained the salient components of the indigenous view. Among other things, he acknowledged that one of the key aspects of the culture is the honouring of the ancestors; according to him, ‘honouring the past is important to create the future.’ 20 Having just left India after the month of Mahalaya when families in Tamilnadu and elsewhere make offerings to their elders, this sounded familiar to me. This was one of the key aspects reiterated by Chief Perry whom we meet in the Lenape Sacred land outside the city of New Jersey. A longstanding Chief of his community and a voice of wisdom, when he talks of what needs to be done in the current world, he talks not from the sense of anger or frustration of being denied access to his own people’s land, but, with a sense of responsibility towards all of humanity. He says, ‘the important ways to change things today are: v Honour the lineage, v Strengthen the local communities, v Perform ceremonies that honour nature and elements, accommodate and accompany others’ ceremonies as well, v Cleanse the earth, v Think beyond our lives.’ 21 After an evening walk around the sacred site and prayers, we asked him before leaving, what was the one thing that he liked to see changed in the world today. After a pause, he replied, ‘If there is one thing that I would like to change in the world with which I think many things can change, I will change the world from the Patriarchal one to one of Matriarchy.’ 22 The denial of access to their land and natural resources resonates in utterances of many of the Native American leaders whether it be in personal conversations or in larger gatherings. Chief Stacey Laforme highlights this in his statement, ‘I was born into a generation of abuse: alcohol abuse; abuse of your spouse, abuse of your children. It was just sort of a common way of life when I was born — I’m sure a lot of it had to do with losing our place in society, losing our sense of who we were. It was rampant and everybody knew about it, but they also didn’t say anything.’ This, ‘not saying anything’ or not having the courage to stand up to injustice is a recurring discussion as well whether it be the engagement with the Native Americans or even in the Parliament of World

Religions in Toronto in early November, which had the Indigenous People as one of its theme. But there is always hope in many of these dialogues, a looking forward to a better world and things improving for the better. This optimism is in contrast to the general sense of frustration and defeated mind-set of many nonNative Americans and also many other European countries. Chief Alina la Flamme, a Chief who evokes response through drumming, calling herself the ‘daughter of the drum’, says, ‘We are in this womb world, we are preparing ourselves to come into the sacred life, it is a tough journey to be born there, it is not easy.’ The same sentiment is resonated in another dialogue with the Hereditary Chief Phil Lane Jr.: ‘Now is the time for everyone to work together, it is not time for divisions, the earth mother calls us all to work together.’ In each of these dialogues and discussions, there is a reverence when they speak of the East Indian land, of our land: ‘You come from a sacred land’, ‘We are honoured that someone from your country is coming to meet us’, ‘Your civilization and ours needs to work together to create a better world, these two

have a great wisdom within them’ – all statements made with great sincerity and gratitude. During these conversations, I often remembered Swami Vivekananda’s words that every word is uttered with blessings behind it. Perhaps through their generations of trials and tribulations, some of the Native American culture and leaders have retained that which is their core – which is their wisdom and capacity to connect to their land and all of nature and to their ancestors. In times of difficulty, every civilization retains that which is core to itself, its fundamental ethos as though protecting it for a future time on behalf of all of humanity. Human history is the history of dominance of the world culture by people of various ethos; in the current times, when the accelerated destruction of natural resources and its consequences on human life has become a major concern of all thinking people, the unconscious collective mind seems to be reaching out to those people and ethos that hold in their midst the possible solutions for these times. These are the indigenous people everywhere. I felt that perhaps some of the Native American leaders sense this invocation

and have started to articulate it with responsibility for all of humanity. It was a fitting tribute to their wisdom and Canada’s long efforts to Truth and Reconciliation, that the Parliament of World Religions 2018 started with a ceremony by the people of the First Nations. As the sacred fire was lit and tobacco, sage, and other sacred materials offered to the fire next to a traditional tepee in the middle of the cloudy, drizzling and crowded city of Toronto, all religious leaders joined the Native Americans.

References

1) http://pluralism.org/encounter/historicalperspectives/parliament-of-religions-1893/ 2) Several sources: ttp://dhayton.haverford.edu/ blog/2012/03/27/columbuss-voyage-was-areligious-journey/ - Columbus and Pierre d’Ailley, Imago Mundi, how the circumference of the earth was under estimated by Columbus based on the works of the theologian http://www.caltech.edu/news/columbus-daillyare-we-there-yet-36981 - why did Columbus put his faith on the d’Ailley more than the contemporary knowledge on the circumference of the world? 3) Letter from Pope Alexander VI to the King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, dated May 4 th , 1493 4) Several sources: https://christianhistoryinstitute. org/magazine/article/why-did-columbus-sail; https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/ issue-35/columbus-and-christianity-did-you-know. html; http://catholicism.org/columbus.html 5) This is not Columbus Day, Betty Lyons, source: https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-opedindigenous-peoples-day-20181004-story.html 6) Relations between English Settlers and Indians in 17 th Century New England, Diploma Thesis by Bc.

Richard Tetek 7) Cronon, The Ecological Transformation of New

England, pg. 20 8) Statements made during conversation with the

Author by Chief Hawk Storm 9) Exiled in the Land of the Free: Democracy, Indian

Nations and the U.S. Constitution. Ed: Chief Oren

Lyons and John Mohawk (1992), pg. 33 10)Basic Call of Consciousness, Ed. By Akwesasne Notes,

Introduction by John Mohawk, pg 81 11)Facing East from Indian Country – A Native History of Early America, by Daniel K. Richter, p 12 12)Origin Stories of the United States: Backdrop -

ReMembering Course by Sequoia Samanvaya, Part II,

Lesson 1 13)Exiled in the Land of the Free: Democracy, Indian

Nations and the U.S. Constitution. Ed: Chief Oren

Lyons and John Mohawk (1992), pg. 44 14)Several sources: https://www.pbs.org/ gunsgermssteel/variables/smallpox.html http://endgenocide.org/learn/past-genocides/ native-americans/ http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/ view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/ acrefore-9780199329175-e-3 15)“The North American Genocide” by Nemattenew (Chief Roy Crazy Horse) – Introduction verses 16)Several sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

List_of_federally_recognized_tribes https://www.usa.gov/tribes; https://www. historyonthenet.com/native-americantribes-nations; https://www.bia.gov/ tribal-leaders-directory 17)https://americanindian.si.edu/nationtonation/ https://www.bia.gov/sites/bia.gov/libraries/maps/ tld_map.html 18)https://www.amazon.in/Kill-Indian-Save-Man

Residential/dp/0872864340 19)Conversation between the author and Chief Perry,

Oct 2018 New Jersey 20)Conversation between the author and Mindahi, Oct 2018, Manhattana, New York 21)Conversation between the author and Chief Perry,

Oct 2018, Lenape land, New Jersey 22)Conversation between the author and Chief Perry,

Oct 2018, Lenape land, New Jersey