8 minute read

Vale Ann-Marie Heine

Industrial Vale Ann-Marie Heine

Ann-Marie Heine, the first woman to hold the position of general secretary of the SSTUWA, died recently in Adelaide where she had lived for many years. Ann-Marie was first elected to the SSTUWA Executive in 1979 at a time when women held few offices within the union. Executive at that time consisted of four women and 15 men. Ann-Marie rose rapidly to become senior vice president in 1982, a position which she held until 1984 when she was appointed by Executive to the position of general secretary. Ann-Marie was a prominent spokesperson for women’s rights both within the union as an Executive member and senior officer, and in a broader social context at a time when women’s rights were being hotly debated across the board. This was a period which saw the appointment of the first SSTUWA women’s advisor, the establishment of the SSTUWA Elimination of Sexism Committee and the active involvement, alongside women from all parts of the community, including the broader union movement, of SSTUWA women in prosecuting the case for the first equal opportunity legislation in WA in 1984. Ann-Marie was possessed of a great wit and was a formidable public speaker.

Advertisement

She articulated the views of many female SSTUWA members who were subject to the extremely conservative rules and regulations which applied to women in the public sector at that time. Within the SSTUWA she led the debate on a number of policy fronts, including the removal of restrictions on the gaining of permanency for women teachers and the consequent access to superannuation. She was also instrumental in the early changes from promotion by seniority towards merit promotion. Ann-Marie argued strongly against the gender stereotyping of deputy principal roles which was then seen as normal, in both primary and secondary schools, and pushed the department to lead by example through the introduction of changes to practice aimed at breaking down some of the entrenched barriers to women’s career progression. This was little more than 10 years after equal pay for women teachers had been introduced. While none of these issues seem at all contentious now, that was not the case at the time. In particular, the move to merit promotion was fiercely resisted and changes to union policy followed only after much heated debate over several SSTUWA conferences.

Views were polarised and hostilities evident over a long period of time. Ann-Marie’s activity extended to the national union – the then Australian Teachers’ Federation (ATF) – where she argued for the same issues at the national level; she also represented the SSTUWA on the Trades and Labour Council of WA, and the ATF at the ACTU committee level. Through her advocacy and example, AnnMarie paved the way for many women in education at the time, both in the Department of Education and within the SSTUWA. Many of the first wave of female principals appointed in the late eighties and early nineties were products of the vigorous representation by the SSTUWA on behalf of women teachers as, indeed, was union policy itself. This union has in recent years had elected representation which closely reflects the composition of its membership at both senior officer and Executive levels. None of these things happen without people who dedicate their energies and skills towards specific goals. Ann-Marie was one of those people. The SSTUWA would like to extend our sincere condolences to Carl and Jason and their families.

Professional High workload and stress levels continue for teachers

By Trevor Cobbold Save our Schools Australia

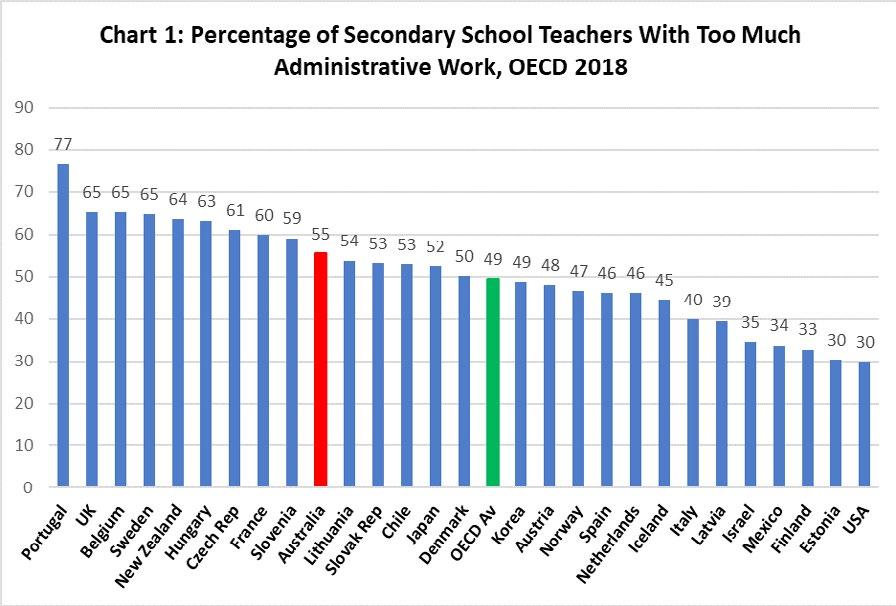

Over half of all secondary school teachers in Australia report that they have too much administrative work, which takes away time for preparing for classes and is a major source of stress. A quarter of teachers say they experience a lot of stress at school. These are amongst the highest percentages in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). They are significant factors behind teachers leaving the profession. Australian teachers also have less professional autonomy over classroom content and assessment than in other OECD countries, but there is more professional collaboration in Australian schools. However, a majority of teachers do not believe their profession is valued by society. These are key results from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), an international survey of school teachers, school leaders and the learning environment in schools released this month. The report provides important insights into the state of the teaching profession in Australia and other countries. The percentage of Australian teachers who report they have too much administrative work and experience a lot of stress is above the OECD average. Fifty-five per cent of Australian teachers say they have too much administrative work compared to 49 per cent across the OECD (see Chart 1). This is the 10th highest percentage in the OECD. Too much administrative work is the major source of stress amongst Australian secondary teachers.

Source: TALIS 2018, Online Table II.2.46.

Twenty-four per cent of secondary teachers in Australia say they experience a lot of stress at work compared to 18 per cent for the OECD (see Chart 2). This is the seventh highest percentage in the OECD. Too much administrative work and acute stress are factors influencing teacher mobility and attrition. Teacher attrition may affect student achievement by having a negative impact on the school climate and on the curriculum. Attrition can also lead to significant financial costs for education systems because of the need to replace qualified teachers in affected schools. On average across the OECD countries and others participating in TALIS, teachers who report experiencing stress in their work “a lot” are twice as likely as colleagues with lower levels of stress to report that they will stop working as teachers in the next five years. In Australia, teachers who report experiencing stress at their work “a lot” are 90 per cent more likely to want to leave teaching in the next five years. In Australia, 22 per cent of teachers report that they would like to leave teaching within the next five years compared to the OECD average of 25 per cent. Twentyfive per cent of teachers in Australia would like to change to another school if that were possible, compared to the OECD average of 20 per cent. On average across the OECD, teachers who would like to change to another school are less satisfied with the profession, did not pick teaching as a first-choice career and are slightly younger and less experienced in their current school than other teachers. The survey results point to the need for much greater support for teachers in schools serving high proportions of disadvantaged students in Australia. Teacher stress is much higher in schools with higher concentrations of students from low socio-economic status families. About 32 per cent of teachers in secondary schools with more than 30 per cent of students from low SES homes report “a lot” of stress compared to 22 per cent in schools with less than 30 per cent of students from such homes. The gap of 10 percentage points is by far the largest in the OECD. As a result, much larger percentages of teachers in schools with higher concentrations of students from disadvantaged homes would like to change schools if it were possible. Thirtyfive per cent of teachers in secondary schools with more than 30 per cent of

Source: TALIS 2018, Online Table II.2.39.

students from low SES homes would like to change schools compared to 23 per cent in schools with less than 30 per cent of students from such homes. Australian teachers also report lower levels of professional autonomy in regards to course content and student assessment than the average for the OECD. In Australia, 73 per cent of teachers report having control over determining course content in their class, compared to 84 per cent on average across OECD countries. Eighty-seven per cent have control over student assessment compared to 94 per cent for the OECD. However, 96 per cent have control over teaching methods, which is the same for the OECD. Professional collaboration provides a foundation for effective teaching practices and although it is low across OECD countries, it is higher in Australia than in most OECD countries. In Australia, 39 per cent of teachers report participating in collaborative professional learning at least once a month compared to the OECD average of 21 per cent. This is the fourth highest percentage in the OECD. There is less team teaching in Australia than in the OECD average with 23 per cent of Australian teachers engaging in team teaching compared to 28 per cent in the OECD. In Australia, 86 per cent of teachers have a permanent contract compared to 82 per cent in the OECD. At the same time, 10 per cent of teachers in Australia are employed on contracts of one year or

less, which is lower than the average of 12 per cent in the OECD countries and economies participating in TALIS. In the last five years in Australia, the proportion of teachers with a contract of one year or less has remained stable.

Most teachers across the OECD don’t feel valued by society. Only 45 per cent of secondary teachers in Australia believe that their profession is valued by society, but this is much higher than the average for the OECD of just 26 per cent. The Australian proportion is the third highest in the OECD, behind Korea with 67 per cent and Finland with 58 per cent. It has also increased from 39 per cent in 2013.

Overall, 90 per cent of teachers are satisfied with their job, which is the same as the OECD average. Moreover, 78 per cent of teachers are satisfied with the terms of their teaching contract (apart from salary), which is above the OECD average of 66 per cent. Also, 67 per cent of teachers report being satisfied with their salaries, which is much higher than the OECD average of 39 per cent.

This article was first published on the Save our Schools Australia website. It has been edited for brevity and clarity.