THE NASSAR DOCUMENTS HAVE BEEN RELEASED THE NASSAR DOCUMENTS HAVE BEEN RELEASED

By State News Staff

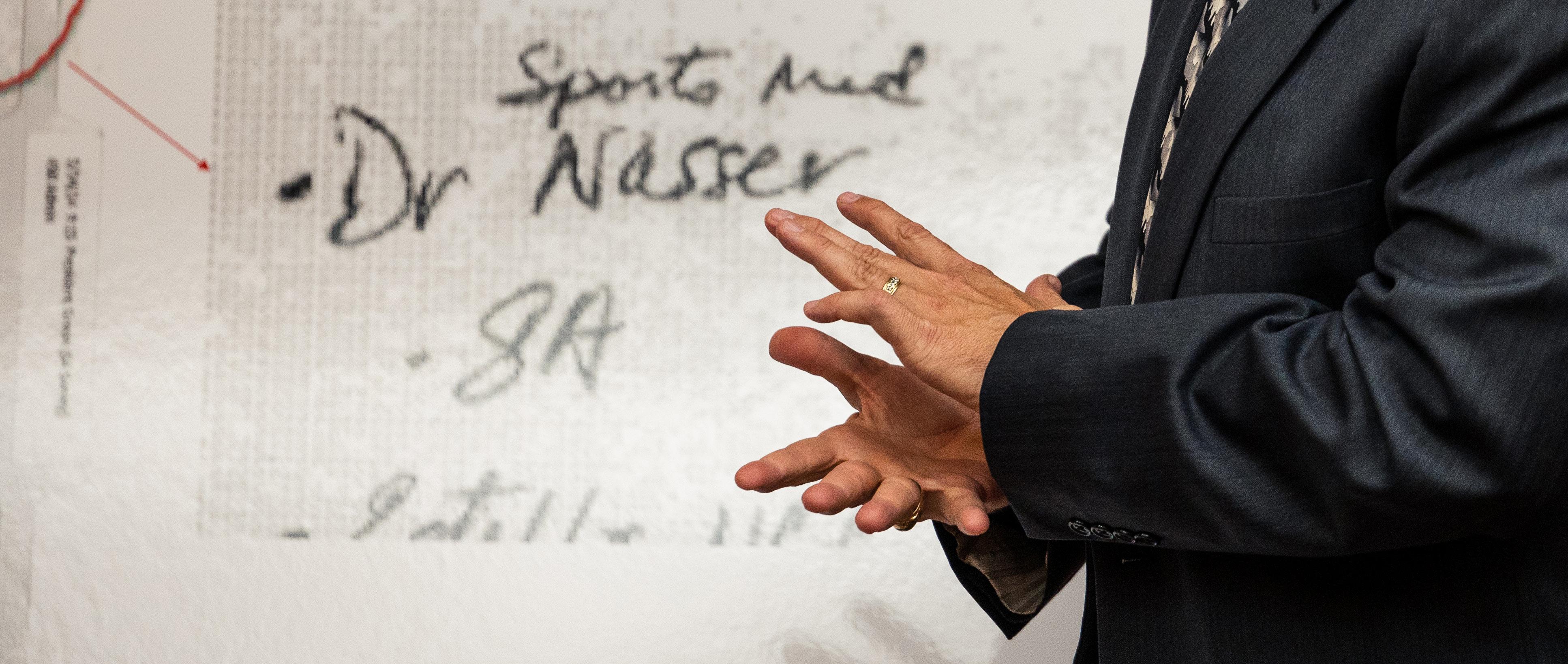

Michigan State University’s long-secret “Nassar documents” have finally been released, giving the public access to a plethora of previously privileged communications and memoranda generated amid the chaos of the scandal.

The State News reviewed every one of the more than 6000 documents. While they do lack the sort of central “smoking gun” some may have hoped for, they are a truly extraordinary insight into a university’s handling of an unprecedented crisis. They are MSU’s true reactions to and strategies for each moment of the Nassar saga, laid bare for all to see.

More stories about the Nassar documents can be found on our website at statenews.com/section/ inside-the-nassar-docs.

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

The State News is published by the students of Michigan State University every other Tuesday during the academic year. News is updated seven days a week at statenews.com. State News Inc. is a private, nonprofit corporation. Its current 990 tax form is available for review upon request at 435 E. Grand River Ave. during business hours.

One copy of this newspaper is available free of charge to any member of the MSU community. Additional copies $0.75 at the business office only. Copyright © 2024 State News Inc., East Lansing, Michigan

MSU OMITTED KEY DETAILS IN 2014 NASSAR CASE

Alex Walters awalters@statenews.com

When Larry Nassar was first publicly accused of sexually abusing his patients in 2016, Michigan State University’s worries immediately turned to a different case.

The one it handled back in 2014, when the famous sports doctor was cleared of sexual assault and allowed to continue his work for the university.

“Once the 2014 allegations come out, and my assessment is it will shortly, that sentiment will only intensify,” MSU spokesperson Kent Cassella wrote in an email hours after the first public report of Nassar’s abuse. The “sentiment” he referenced was brewing speculation that MSU had allowed Nassar’s abuse to continue.

The 2014 allegations did come out, and they certainly fueled the idea that MSU played a role in Nassar’s ability to avoid consequence for so long. But, the university has long been able to aggressively downplay those claims.

Administrators have said that the allegations made in 2014 were less severe than those later made publicly because what was reported wasn’t inherently sexual. The investigator who handled the case has even been promoted in the years since.

But, long-secret documents are now revealing that behind closed doors, MSU had deep doubts: the university knew that crucial evidence was omitted, swaying the results in Nassar’s favor.

All the while, the survivor who reported Nassar was left with a decade of doubt and “self-hatred,” wondering why they weren’t believed.

SURVIVOR BLAMED THEMSELF

When Amanda Thomashow reported

Nassar to MSU in 2014, they thought they told investigators that he had an erection as he groped them during an appointment, they told The State News.

The detail was essential to their allegation that Nassar had sexually assaulted them under the guise of medical treatment at his office on campus.

But, nothing about arousal made it into MSU’s final investigative report.

The omission supported the university’s determination that Nassar did not assault Thomashow, and that his groping was all part of legitimate medical treatment for their sports injuries.

After receiving the report, Thomashow questioned themself, wondering if they somehow forgot to mention his arousal to investigators, or didn’t make it clear enough.

It felt like a sort of “gaslighting,” Thomashow said. The report clearing Nassar — and MSU’s subsequent denial that the university made mistakes in doing so — convinced Thomashow that they must have been wrong.

“It messes with your mind,” they said. “(MSU) convinced me that I was crazy for letting the assault bother me so much.”

They reached “a new level of self-hatred” in 2016, as hundreds of other survivors started coming forward with allegations against Nassar.

Thomashow became sure they were assaulted, but wondered if some of the other cases were their own fault, they said.

Many of the survivors coming forward were assaulted after 2014, after MSU cleared Nassar in Thomashow’s case. So, Thomashow began to worry that if they had just mentioned the erection, MSU would have sided against Nassar, fired him and the other survivors wouldn’t have been abused, they said.

New documents, however, suggest

Thomashow did tell MSU’s investigators about the erection — they just mysteriously left it out of their report.

A CRUCIAL OMISSION

In 2017, MSU conducted a sort of autopsy of Thomashow’s case: re-interviewing those involved and going through all investigator’s files.

Memos summarizing that autopsy greatly challenge the findings in the 2014 investigation. Some of them were among the thousands of long-privileged MSU documents recently released by Michigan’s attorney general. The State News obtained others from a person involved.

In the original notes from Thomashow’s interview, there are two references to Nassar being aroused, according to one of the memos.

The interview was conducted jointly by Kristine Moore, an MSU Title IX investigator, and Valerie O’Brien, an MSU Police captain.

“Enough to be little too much (in crotch),” they wrote in their notes, according to the autopsy.

They also noted that Thomashow said Nassar “went to corner of room 30-45 sec doing hand sanitizer. I thought weird — maybe erect.”

Neither observation was mentioned in their final report.

The final report also made no mention of statements from Nassar’s department chair, Jeffrey Kovan. He told investigators it would not be appropriate or medically necessary to touch a patient inside of their underwear, the autopsy found. The report also didn’t include information about Nassar’s Facebook page getting banned “because of all the young girls,” one memo said. It’s unclear exactly what that note refers to.

O’Brien has since left MSU Police. In 2020,

she was demoted for making “inappropriate comments” and then was charged with drunk driving in 2021.

Moore was promoted in 2014, shortly after issuing Thomashow’s report. She now serves as an associate general counsel in the university’s legal office.

MSU declined to comment on the issues with the 2014 report. O’Brien could not be reached.

In the 2017 autopsy, O’Brien did offer a partial explanation of the omissions. She said that Thomashow didn’t actually tell them Nassar was aroused. Instead, O’Brien said she and Moore added the various references to an erection into the notes after the interview was over. They were only “speculating,” she said.

“(We) simply discussed whether that might have been the case,” O’Brien said, according to the autopsy.

That defense was questioned by even the PR consultants MSU hired to design responses to the Nassar issue.

In a report prepared for administrators, consultants from Blue Moon Consulting Group wrote that the omission of the arousal notes could be disastrous for the university’s image. Because, as the consultants said, “Would that fact have changed not only the internal investigation but also the review of the local prosecutor?”

Thomashow said they never “got the sense” that anyone at MSU believed the university had truly mishandled their case. Instead, they were repeatedly told the outcome was their fault for not mentioning the erection.

“I asked over and over, why wasn’t I believed when (other survivors) were,” they said. “The big difference was the erection, they said that was the difference.”

“But they knew,” Thomashow said.

HOW MSU’S FAULTY RECORD-KEEPING OF NASSAR DELAYED SCRUTINY

Theo Scheer tscheer@statenews.com

Text messages were deleted. Investigatory files went missing. Documents were withheld. When state investigators requested records detailing Michigan State University’s handling of Larry Nassar, many didn’t realize that they weren’t being given the full story.

Thousands of recently released documents reveal that the university’s records-keeping, when it was needed the most, was laden with mistakes.

A former university president admitted she deleted personal text messages when an investigation required a probe of her phone. Nine investigatory files needed by an outside Title IX attorney went missing for months because a department didn’t organize its files.

And the very documents that reveal these missteps? MSU refused to hand them over to Attorney General Dana Nessel for years, delaying her investigation into Nassar and prolonging survivors’ hope of accountability.

Nessel concluded her investigation less than two weeks ago, saying the thousands of documents about MSU’s handling of Nassar contained information that was “embarrassing” for the university, but not “incriminating.”

What was clear, Nessel argued, is that MSU wrongly withheld the documents for years.

ATTORNEY CLIENT PRIVILEGE?

MSU has long said the documents are subject to “attorney-client privilege,” which protects communications between a lawyer and their client from being publicly released. Many of the documents outlined the university’s communications strategy, not legal conversations. Others were shown not to be privileged by their own authors’ admission.

Kristine Zayko, MSU’s deputy general counsel, advised several MSU officials that

their communications were not protected by attorney-client privilege.

“ ... putting privileged & confidential on the top of these does not make them privileged,” Zayko wrote to one colleague who had included the phrase at the top of an email about PR strategy. “They would still get released under a (Freedom of Information Act request) since they are not actually seeking any legal advice.”

Zayko issued the same reminder to Trustee Dianne Byrum after she distributed a “privileged” media protocol for board members to consult during the heights of the Nassar scandal.

MSU Spokesperson Emily Guerrant defended the university’s withholding of the documents, saying that Zayko was giving university officials legal advice — which, in itself, would be considered privileged information.

DELETING, AVOIDING TEXTS

In January 2018, as MSU’s general counsel was reminding employees to retain their communications for the newly-begun attorney general investigation into Nassar, former President Lou Anna Simon admitted she had a habit of deleting her text messages.

“As you are aware I have always treated text messages as the equivalent of oral communication and deleted,” she wrote. “However, I did this with the understanding that all were available through a request that I could make or through legal avenues.”

Simon’s husband, a facilities employee named Roy, had been doing the same, she later said.

“For years, he has answered all email he receives as soon as possible, often the same day, and then deletes,” Simon wrote in an email to then Assistant General Counsel Brian Quinn later that month, adding that she didn’t recall using Roy’s belongings to communicate

about Nassar.

Another MSU employee was seemingly trying to prevent such records from being created in the first place.

Kathie Klages, a former university gymnastics coach, told student-athletes “that they might not want to text back and forth about Nassar, that they should talk on the phone if they wanted to discuss,” Zayko said in an email recalling a conversation with her in January 2017.

Klages was convicted in 2020 for lying to police about her knowledge of Nassar’s abuse, but the conviction was later overturned.

MISSING FILES

In 2016, university staff discovered they hadn’t given the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights all the sexual abuse investigatory files an investigator had previously requested for a review.

MSU’s newly created Office of Institutional Equity quickly began an audit to see what else was missing, according to a memo sent to Simon about the error in March 2017.

The university found a total of nine files — including one about Nassar — that weren’t given to the investigator because the department that first compiled them failed “to implement any sort of file organization system.”

Former university psychologist Gary Stollak, who surrendered his license in 2018 after failing to inform authorities of Nassar’s suspected abuse, also had a problem with missing records.

Stollak didn’t have access to his patient records because he destroyed them all, Stollak’s attorney, Peter Cronk, told MSU in April 2017.

“Stollak’s home was broken into twice several years ago,” general counsel Quinn wrote, recalling a prior conversation with Cronk. “One time, patient records were

removed. So Stollak destroyed all his records.”

FIGHT OVER DOCUMENTS’ RELEASE

The university’s withholding of the thousands of documents related to its handling of Nassar has been a source of controversy for years. The decision inspired a lawsuit and continual pleas from survivors.

Throughout it all, MSU defended its withholding of the records.

Trustee Renee Knake Jefferson, who read the documents before they were released, said in 2020 that the documents didn’t contain any new information about the administration’s handling of Nassar. A year prior, East Lansing District Court Judge Richard Ball ruled that MSU had appropriately applied attorneyclient privilege to the documents.

Without access to the documents, Nessel closed her investigation into Nassar in 2021. But in 2023, with the election of new board members who voiced support for releasing the documents, Nessel reopened her investigation into “how and why the university failed to protect students” from Nassar’s abuse for so long.

In December of 2023, MSU’s Board of Trustees voted unanimously to send those documents to Nessel’s office.

Nessel completed her investigation and publicly released the documents nearly two weeks ago. But the move, not unlike MSU’s record-keeping, didn’t go smoothly.

Nessel’s office had to temporarily remove access to some of the documents days after releasing them to the public, because the office didn’t fully redact names and information about survivors in them. But even after the documents’ rerelease, some survivors’ names remain unredacted.

Administration Reporter Owen McCarthy and Senior Reporter Alex Walters contributed reporting.

‘Only listening to defend’: MSU closely monitored survivors amid Nassar crisis

Theo Scheer and Alex Walters tscheer@statenews.com, awalters@statenews. com

In hundreds of victim impact statements at Larry Nassar’s sentencing, survivors talked about more than the disturbing details of the disgraced ex-doctor’s serial sexual abuse.

Some of the statements’ most stirring moments were instead about the people and organizations that allowed him to go unchecked for so long.

The top administrators at Michigan State University, Nassar’s longtime employer, and a subject of much of the contempt, did not attend any of the nine days of statements, a decision criticized by survivors.

They were, however, listening — in a way.

Previously secret legal documents reveal that the university paid attorneys to watch the impact statements and take detailed notes, in hopes of learning more about the looming barrage of civil lawsuits from survivors who accused MSU of allowing the abuse.

In a series of memos, MSU’s lawyers sorted the survivors. Those who had sued the university, or voiced an intention to, were closely watched. The lawyers transcribed parts of their testimony that accused MSU of negligence or provided details of the severity of their abuse.

“We had asked leadership, ‘Please come listen to us,’” said Rachael Denhollander, a survivor who delivered a 36-minute impact statement that focused heavily on MSU’s role in allowing her abuse. “Not only did they fail to do that, they sent lackeys to engage in a voyeuristic exposé

of the abuse so they could craft a litigation strategy without our knowledge.”

“That’s nasty,” said Denhollander, who was the first woman to publicly accuse Nassar of sexual assault.

The courtroom memos are among thousands of documents that MSU withheld from investigators and the public for years, citing attorney client privilege. After pressure from survivors and activists, the university’s board released them to the state attorney general late last year. She closed her investigation and released the documents to the press last week.

The newly public records provide the fullest picture yet of the ways the university monitored and categorized survivors of Nassar’s abuse.

Lawyers were tasked with monitoring survivors’ public statements in hopes of staying one step ahead of numerous civil suits; an investigator was hired to find other survivors before they publicly came forward. The university even hired a firm to rank survivors with numerical scores quantifying the severity of their abuse.

The university also hired lawyers to research the backgrounds of women — some survivors, some not — who had signed up to speak at board meetings, a frequent venue for criticism of the university. In one write-up on future speakers, MSU’s lawyers even made detailed notes of old Facebook comments and where each person went to high school.

GETTING AHEAD OF LITIGATION

In addition to the memos, which sought to learn about the survivors who told their stories during the criminal proceedings

against Nassar, MSU also hired an investigator to find new allegations before they came to light.

The practice became a source of controversy in 2018, when a studentathlete alleged that the investigator, Bill Kowzlski of Rehmann Corporate, had outed her as a Nassar survivor while questioning her coach. Lawyers representing other survivors went further, criticizing the university for “investigating victims” at all.

At the time, MSU tried to downplay the allegations. But the new documents include internal communications in which the university seems to concede to the criticisms.

Emails show that after the outing accusation, some MSU administrators and lawyers demanded a strong defense to dispel the claim. But they ultimately took a middling approach, as a full defense could not be done truthfully.

In the first draft of a response to the allegation, an MSU spokesperson suggested saying that “at no time did the university engage in any activity to investigate plaintiffs themselves.”

One of the lawyers disapproved, saying it would be inaccurate to assert that the firm had never investigated plaintiffs in the past. They suggested changing the tense to only say the firm “is neither investigating plaintiffs themselves nor interviewing them.”

Other lawyers and administrators wanted something stronger. But again, they were told it couldn’t be done truthfully.

“Everyone on this thread seems confused as to where this is coming from,” spokesperson Jason Cody said

in an email. “We hired an investigator. That investigator likely did exactly what was alleged.”

SORTING IN LITIGATION

As the number of women suing the university rose to the triple digits, MSU began using elaborate methods to categorize the plaintiffs and their claims.

Records show MSU had a financial consulting firm assign survivors scores from 0-100 based on the severity of abuse they experienced.

The factors powering the formula included the nature and frequency of abuse, survivors’ age at the time, and whether they made ignored reports to MSU.

The firm used the survivors’ “severity value” to calculate the expected amount MSU could end up paying after the litigation.

“As crass and reductive as it feels,” that sort of math is a necessary part of a settlement like the one survivors won, Denhollander said.

MSU sees it the same way, said spokesperson Emily Guerrant. “This legalese — while a necessary component of the settlement process — does not adequately convey the extent of our commitment and compassion for survivors,” she said in a statement.

That defense may be hard to believe, Denhollander said, “when you mix it with all this other stuff.”

“It seems they were not interested, in any way, in any sort of real change,” she said. “It was only listening to defend.”

Administration Reporter Owen McCarthy contributed reporting.

By Alex Walters, Owen McCarthy and Theo Scheer

awalters@statenews.com

omccarthy@statenews.com tscheer@statenews.com

With every new, damning allegation against Michigan State University’s handling of the Larry Nassar crisis, administrators thought they faced a choice — win in the court of public opinion today or prevail in the court of law down the road.

The frank, internal communications of the university, which were released last week among thousands of Nassar-related documents, reveal a constant push and pull between the PR pros tasked with salvaging MSU’s image and the droves of lawyers hired to minimize the university’s legal exposure.

Some administrators pushed for a more forthcoming strategy: owning up to mistakes, correcting misinformation before it spread and emphasizing the university’s desire to improve going forward. Their attorneys, however, disagreed, arguing that any concession made in the press could come back to bite them in court.

In almost every instance, the lawyers prevailed, putting potential advantages in legal proceedings above any attempt to recover the university’s embattled reputation.

The rationale for that approach was explained at length in a memo by thenGeneral Counsel Robert Noto. He wrote that plaintiffs’ attorneys were using the media to bait MSU into saying the wrong thing, which he feared would further the pressure on MSU to reach a settlement with survivors.

“We do not want to say something that will tip our hand or give them information they don’t have or can later use,” Noto wrote. “We are also cognizant of the extreme fuidity of the situation and not anxious to say things based on present circumstances that can be thrown back at the University if the situation changes in the future.”

Noto compared it to a “fght in a ‘Rocky’ movie.”

“We are going to have to take a lot of punishment before we can dish a lot out, and most of the punches we land aren’t going to cause damage which will be as visible as what results from theirs,” he wrote.

The success of the strategy was dubious. MSU ended up paying a $500 million settlement to survivors, one of the largest amounts a U.S. university has paid in a sex abuse scandal.

Rachael Denhollander, the frst woman to publicly accuse Nassar of sexual assault and the lead plaintiff in one of the lawsuits, said Noto’s strategy likely had the opposite effect. Had MSU apologized to survivors and listened to them about reforms, many would not have sued, she said.

“I think they could have avoided liability in the vast majority of these cases,” Denhollander said. “That was the heartbeat of survivors, that ‘I just don’t want to see this happen to anyone else.’”

“They thought only in terms of liability,” she said.

The tension between protecting MSU’s image and protecting it from a settlement emerged in the drafting of many public statements related to Nassar.

SAVE IMAGE OR INFLATE SETTLEMENT

In one of the frst university-wide letters addressing Nassar, some administrators wanted to say MSU would “ensure” students’ safety going forward.

General Counsel Noto suggested they instead write that “we at MSU will give the highest priority to the safety of our patients and the protection of youth who come to our campus,” records show.

When drafting a letter to then-Attorney General Bill Schuette requesting his offce begin a review of MSU’s handling of Nassar in January 2018, PR staff originally wrote that the university’s goal was “to answer the public’s questions concerning MSU’s handling of the Nassar situation.”

But the request was too close to an admission of wrongdoing for the legal team.

The success of the strategy was dubious. MSU ended up paying a $500 million settlement to survivors, one of the largest amounts a U.S. university has paid in a sex abuse scandal.

Outside counsel revised the statement to say an AG review “may” be needed, though the university has confdence in the litany of reviews already conducted into Nassar.

MSU’s communication team and a PR firm, Weber Shandwick, disagreed with the revisions.

“By inserting these arguments before we ask for help, we reduce the PR value,” wrote Heather Swain, then MSU’s vice president for communications and brand strategy.

But MSU’s then-board Chair, Brian Breslin, ended up approving the more defensive statement, records show.

Concerns over the “PR value” of statements also plagued MSU’s response to an April 2017 Washington Post editorial on MSU’s “willful blindness” to Nassar’s abuse, which followed the newspaper’s detailed investigation into university offcials’ failure to act.

In initial drafts of the university’s response, university counsel wrote that the editorial was drawing “conclusions based on allegations by plaintiffs in lawsuits, many of which have not yet been served on, what’s more answered by, the University, or upon the incomplete picture provided by the documents thus far released by MSU through the Freedom of Information Act process.”

There was immediate pushback from MSU’s communications team, arguing the statement was overly legal and didn’t express any sympathy for survivors.

MSU leadership needed to understand that “a reasonable person could easily come to the same conclusion that the editorial did” after reading The Post’s “100% accurate” initial investigatory piece, then-spokesperson Jason Cody wrote. The statement needed to be infused with “apology and empathy,” or not sent at all, he said.

Lawyers also clashed with board members.

In 2018, Noto and former Trustee Melanie Foster disagreed over whether or not to pull indemnification for William Strampel, the former dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Strampel had recently been handed dismissal charges by MSU for violating the university’s sexual misconduct policy. Months later, Strampel would be arraigned on federal charges of sexual misconduct and willful neglect of duty.

While it’s common practice for institutions to cover legal expenses for staff who are facing litigation, the institution can revoke that protection if the person refuses to cooperate with the legal proceedings.

“We do not want to say something that will tip our hand or give them information they don’t have or can later use.”

Robert Noto

Former General Counsel

Foster argued that Strampel’s expressed intention to fght the dismissal charges the university had handed him provided suffcient grounds to pull his indemnifcation.

But Noto disagreed, saying indemnifcation can’t be pulled for the sole reason that Strampel refused to cooperate with the university’s request for his dismissal.

Noto conceded that Strampel was an “embarrassment” and had indeed refused to cooperate with the university’s request for his dismissal, but said that wasn’t enough to legally justify pulling indemnifcation.

“If he sued us for his defense and indemnity costs after we pulled them (and he likely would now that he has lawyered up), he’d probably win.”

In at least one case, MSU’s legal caution went so far as to stop administrators from correcting a rapidly spreading, damning story they believed to be untrue.

In January 2018, a Nassar survivor testifed in court that her family was still being billed for appointments she had with Nassar.

The story generated the most media attention of any development throughout the entire Nassar saga up to that point, thencommunications director Kent Cassella said. Cassella recommended the university act swiftly in response, and “make a blanket decision to stop billing all Nassar patients immediately.”

But shortly after, then-CEO of the MSU HealthTeam Michael Herbert notifed the communications team that the subject of the

Rachael Denhollander, the first woman to publicly accuse Nassar of sexual assault, said Noto’s strategy likely had the opposite effect. Had MSU apologized to survivors and listened to them about reforms, many would not have sued, she said.

media report did indeed have an outstanding payment — but just not with Nassar.

Instead, Herbert said, the appointment was with another physician, Jeffrey Kovan.

The university moved the same day to cancel the outstanding bill in response to public pressure, but declined to contest the truthfulness of the media report — a decision that drew the ire of Trustee Dianne Byrum.

“We should correct the information in the press if the person did not see Nassar,” she wrote. “We should pivot to more offense, correct all misinformation and leave no attack unanswered.”

The reasons then-communications director Jason Cody gave for not correcting what the university believed to be an inaccuracy were two-fold.

“I don’t like the idea of any of us having access to medical records. Or calling out a teenage victim.”

Heather Swain cited the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, a law that protects the privacy of health information, as a legal obstacle to giving the media information about the person’s health records and asking them to run a correction accordingly.

In some cases, after all the tweaking and fghting, MSU’s spokespeople wondered if any statement could save them. Or, if the university’s actions were simply indefensible.

Since you lawyers wouldn’t do the right thing … there ain’t crap the media folks can do for you

Cody wrote in a text message to Cassella, expressing frustrations about the university’s decision not to fre MSU doctor Brooke Lemmen, who at the time was accused of removing patient fles at Nassar’s request.

...and klages, and Strample, and training, and outreach, and …

Cassella wrote back, referencing other areas where the PR professionals found it diffcult to defend the university’s actions.

By Alex Walters, Owen McCarthy and Theo Scheer

awalters@statenews.com omccarthy@statenews.com tscheer@statenews.com

Michigan State University was in a “war,” its top lawyer believed.

Its cause? Save the university’s image and prevent a massive settlement.

Its enemy? The hundreds of women, represented by a cadre of brash attorneys, about to sue MSU over years of unchecked sexual abuse by one of its doctors, Larry Nassar.

The confict could only be won, thengeneral counsel Robert Noto wrote, “by the opponent’s loss of will to fght, by a lack of support on the home front, a desire to move on to other things,” or “by overwhelming defeat on the battlefeld or strategic error.”

“We are going to have to take a lot of punishment before we can dish a lot out … this is going to be a lot like the fght in a ‘Rocky movie,’” he wrote in a 2017 “thinking paper,” which was publicly released for the frst time last week by Michigan’s Attorney General, among thousands of other longsecret MSU documents.

To see the Nassar crisis through those documents — written by people who believed their communications would never be publicized — is to view it through a wholly new lens.

In statements from survivors, and years of memoranda from the various law enforcement, regulatory and legislative investigations, MSU has been a villain in the Nassar affair: criticized for enabling Nassar for so long.

But in these documents, MSU’s lawyers and leaders seem to see a completely different landscape. In their framing, the university is a victim facing unfair attacks from every direction.

As they put it, survivors are dangerous liabilities who require constant oversight, able to create a crisis with each new allegation. Their attorneys are “ambulance-chasers,” manipulating their clients to serve their greed. The press is their “willing ally,” hungry for anything that skewers MSU. The various investigators are a foe to outmaneuver, and a source of constant stress.

There were moments when some questioned the war-games, but they were scarcely acknowledged. As Noto said of the metaphorical battlefeld, “if we are not willing to live with that dynamic, it would be wise to throw in a towel…”

Reached for comment, MSU denied that a similar tone is currently used when discussing issues of sexual violence. “This has not been my experience while working at MSU,” spokesperson Emily Guerrant said.

‘LARGE EGOS’

University counsel held a deep disdain for many of the attorneys who brought survivors’ lawsuits against MSU, internal communications reveal.

FOR MSU, SCANDALNASSAR WAS A

John Manly, a California attorney who represented hundreds of Nassar survivors, was a particular source of frustration.

When Manly criticized the university for only offering “cheap PR words” to those affected by Nassar’s abuse at a press conference, university spokesperson Jason Cody texted a colleague, “Guess him and I aren’t buddies.”

“He’s a jerk,” Deputy General Counsel Kristine Zayko responded. “You must be doing a good job if he’s mad at you.”

When Manly wrote a blistering email saying his clients distrusted a new fund for survivor therapy — comparing the university to the Catholic Church — some of MSU’s lawyers reacted with snark.

Attorneys were described as “arrogant,” “aggressive” and “impolite.” Some had “large egos.” One Lansing attorney was “unreasonable at times” and had been known to “push the counsel wrote. distasteful cash-grabs. Press conferences were described as “grandstanding.”

Nassar folds up the paper with his statement on the third and final day of sentencing on Feb. 5, 2018 in the Eaton County courtroom. Nassar faced three counts of criminal sexual conduct in Eaton County and was sentenced up to 125 years. State News File Photo.

‘WAR’TO BE WON

“The more sensational the charge the better for the press…” wrote Noto, who declined to comment.

Throughout the documents, administrators appear to feel victimized by what they saw as a news media unfairly capitalizing on their own struggle and printing anything to grab readers’ attention, regardless of its journalistic integrity.

“Can we sue them.”

Such was former President Lou Anna Simon’s blunt question to university counsel in reference to the Washington Post, which had recently published an editorial criticizing MSU for its handling of Nassar.

Emails show that lawyers and MSU administrators were upset with the piece, and quickly began working on a response to the newspaper.

The editorial was based on “incorrect assumptions” and drew conclusions without providing time for litigation and independent and internal investigations to complete their work, they wrote.

Another story that drew ire from MSU was an ESPN “Outside The Lines” special called “Michigan State secrets extend far beyond Larry Nassar case.”

The article claimed to have uncovered a widespread pattern of inaction with regards to sexual violence, and cited allegations of sexual assault in the basketball and football programs, under the watch of “MSU’s most recognizable fgures,” former football coach Mark Dantonio and basketball coach Tom Izzo.

The perceived false equivalence between the coaches and Nassar was a particular point of contention in a draft of a letter MSU planned on sending to ESPN contesting the integrity of the piece.

“Your insinuation that coach Tom Izzo and Mark Dantonio have anything to do with the Nassar situation is ‘Outside the Lines.’”

The letter also suggests ESPN was in no position to report on mishandling of sexual abuse given its own record.

“I’m going to start taking bets on how quickly he responds to emails in the future,” Miller Canfeld attorney Scott Eldridge wrote to colleagues. “He just can’t help himself. He’s

In another exchange, Noto called Manly “impolite” for requesting that an additional university representative join a scheduled

Manly, in an email to The State News, wrote, “For the record, I am impolite to people in positions of authority who protect pedophiles.”

Eldridge also ridiculed Andrew Abood, another prominent attorney for survivors, for attempting to “plug (his) new restaurant/bar in town” in a radio interview about MSU’s role in Nassar’s abuse. (Abood could not be reached

As Noto put it in his “thinking paper,” the press were plaintiffs’ attorneys’ “willing ally or easy dupe.”

“ESPN as an organization has had numerous recent issues with employees accused of sexual assault, sexual harassment and discrimination, I would think you would have a heightened level of sensitivity to these issues and that would be refected by a more accurate level of reporting,” the drafted letter said. “Unfortunately, that has not occurred.”

Communications directors also poked fun at reporters, saying one was working on their “investigative pulitzer” and trying to “outdo IndyStar,” in reference to the outlet whose report on Nassar’s sexual abuse set off the scandal in 2016.

Over time, the attitude among administrators towards harsh media coverage devolved into helplessness.

In March 2017, for example, a spokesperson warned administrators that NBC Nightly News was about to air a segment on MSU’s handling of Nassar’s abuse, which featured a sit-down interview with a current student-athlete.

In response, then-Provost June Youatt simply wrote: “Ugh.”

NEW DOCUMENTS REVEAL FULLER PICTURE OF MSU’S PRESIDENT SIMON

awalters@statenews.com, omccarthy@

As the Nassar scandal swelled, Michigan State University’s president, Lou Anna Simon, was getting “antsy.”

While surrounded by her peers at a meeting of the Association of American Universities, emails show she asked university lawyers for input on an idea: personal letters of apology to survivors of Nassar’s abuse attached to their Title IX reports.

Simon asked for notes on a draft. It said, “I would like to personally say I am sorry for what happened to you and I truly appreciate the courage you have shown in stepping forward.”

It was the sort of apology critics had been demanding from the increasingly-embattled president — the kind of apology she didn’t actually make until almost a year later, to mixed reviews, just before

It took so long, the emails suggest, because MSU’s lawyers were staunchly against any sort of apology.

They saw it as an admission of guilt, which could result in costly consequences in civil litigation brought by survivors. More broadly, they said an apology would be “thrown back at us” as “evidence of a pro-complainant bias” in any future sexual violence issues, Nassar-related

The appetite for an apology — revealed by emails among thousands of long-secret MSU documents released by Michigan’s Attorney General last week — is one brushstroke in an increasingly nuanced portrait of Simon that has emerged in the years since the height

Her legacy is dominated by some of her most notorious moments, such as her absence from victim impact statements at Nassar’s trial or the continued intrigue about what she was told about him in an infamous 2014 meeting. The newly-public documents do, in some ways, cement that perception.

But, they also reveal a president beset by the constraints of her office.

She was largely defensive about Nassar, but also had an intermittent

appetite for accountability. And, in moments like the apologies, she sometimes seemed open to survivors’ demands, but deferred to lawyers who told her to put safety from future litigation first.

“She may have actually had the right instincts a lot of the time, but she was hampered by her general counsel, who she listened to when she shouldn’t have,” said Rachael Denhollander, the first woman to publicly accuse Nassar of sexual assault, and the intended recipient of one of Simon’s draft apologies.

DELETION AND DEFENSIVENESS

As Attorney General Dana Nessel pointed out in her announcement that the documents would be released, they do include one truly unflattering revelation against Simon: that she deleted key records relating to her handling of Nassar.

MSU general counsel sent a memo to remind university personnel of their “document preservation obligations” in light of an information request from former Attorney General Bill Schuette in January 2018. In response, Simon admitted she had been in the habit of deleting her text messages.

“As you are aware I have always treated text messages as the equivalent of oral communication and deleted,” she wrote. “However, I did this with the understanding that all were available through a request that I could make or through legal avenues.”

Later that month, Simon admitted in an email to then-Assistant General Counsel Brian Quinn that her husband, Roy Simon, who worked at the time in MSU’s Infrastructure, Planning and Facilities department, had also been regularly deleting text messages.

“... I do not recall using any of Roy’s devices for communication regarding Nassar or other matters related to sexual assault. Yesterday, in phone call to check on me, I told Roy that we needed to be more careful moving forward. Not to hide but to retain…”

Her husband is “a compulsive,” she said, adding that “he has answered all email he receives as soon as possible, often the same day, and then deletes.”

The documents also reveal that

while she did want to generally apologize to survivors, Simon was sometimes adamant about including defensive language in MSU’s communications on Nassar-related issues.

In one case, Simon suggested that a statement defending MSU say it is “impossible to stop a pedophile” like Nassar. When lawyers and PR advisors objected to that framing, she doubled down.

Simon suggested that another statement should say Nassar’s abuse was more difficult to discover because it was conducted under the guise of medical treatment. The PR and legal teams had concerns about that framing, too.

“... I do not think it is helpful on the PR front. Sounds more like an excuse or defensiveness …” said communications director Heather Swain.

Simon also railed against critical media coverage by imploring staff to prevent negative stories.

In one case, she asked MSU’s general counsel if the university could sue The Washington Post over an editorial that criticized her administration’s “willful blindness” to Nassar.

After a series of unfavorable stories about sexual misconduct unrelated to Nassar, spokesperson Jason Cody texted a colleague, “It’s been a crazy few days, more football rapes and getting yelled at by (Simon).”

“Typical MSU!” he added.

A HANDS-ON ROLE

The documents also shed new light on Simon’s level of day-to-day involvement in the Nassar fallout.

Some emails show sudden bursts of interest from Simon, with intense demands about compliance with various investigations.

Documents show that in January 2017, administrators circulated a media report that detailed a court filing alleging that an MSU representative told a woman’s sports team months earlier not to talk to police about Nassar.

Simon was taken aback in her reaction, saying “contrary to all expectations,” the university had been encouraging all staff “to go to police and be forthcoming.”

“Need to get to the bottom of

this quickly and take appropriate disciplinary action if our review indicates that staff are impeding efforts to investigate,” she wrote.

Aside from her expressed desire to hold accountable anyone at MSU impeding investigations, one document suggests Simon was in favor of MSU directly contacting former athletes and patients with potential knowledge of Nassar’s abuse.

It’s unclear if the proposed letters were intended to encourage recipients to report abuse from Nassar.

“(Simon’s) primary question is what the scope and purpose of our communication will be,” wrote thenGeneral Counsel Kristine Zayko. “... Is it tied to our review of athletics? Is it tied to a specific purpose with HealthTeam? Or is it simply, Nassar was a bad guy and if you want contact information, here it is? (Simon) wants some options to react to.”

Simon even appeared to have assisted MSU’s internal investigation into who may have had knowledge of Nassar’s abuse. She compiled several lists of employees whose emails she wanted to be searched, according to emails between university counsel and the chief information officer from January 2017.

Simon also tried to keep control over the long-term strategies of certain departments. At one point, she asked a large group of administrators to read a series of lengthy screeds written by a zealous alum who compared MSU’s Nassar issue to Pennsylvania State University’s sexual violence scandal.

“Per President Simon, please review and suggest a response, and advise if there is anything useful,” wrote an assistant who shared the writings with Simon.

In fact, Simon seemed to consistently read emails sent to “presmail@pres.msu.edu” from various alumni or truly unconnected onlookers. Repeatedly, she asked administrators to consider their messages and draft responses. But, she was told the university should not respond to every message her office received.

Eventually, they settled on only responding to messages from significant university donors.

Administration Reporter Theo Scheer contributed reporting.

CURRENT MSU VP TRIED TO ‘JUSTIFY’ NASSAR’S ABUSE IN 2018 MEETING

Alex Walters awalters@statenews.com

One of Michigan State University’s current top administrators made comments that attempted to “justify” the serial sexual abuse of disgraced ex-MSU doctor Larry Nassar, a long secret document reveals.

At a meeting for campus workers in 2018, Senior Vice President for Student Life and Engagement Vennie Gore said that “a very large majority of the women did not understand that it was a medical procedure.”

Gore also defended former President Lou Anna Simon, who, at the time, had just resigned over what critics called a mishandling of Nassar that empowered his years of unchecked abuse.

The comments were made public last week, when Michigan’s Attorney General released thousands of internal MSU documents related to Nassar.

While a vast majority of the documents regard administrators who have left MSU in the years since the scandal, these records of Gore’s meeting include a harsh reproof of one of the most powerful people in MSU’s administration today.

The comments were reported to MSU’s Office of Institutional Equity by a survivor of Nassar’s abuse who was among those in the room. She left the meeting “crying and very upset,” an investigator noted.

The concerns were forwarded to Gore’s superiors, as they were more so an “HR issue” than a matter for the Office of Institutional Equity. In a meeting with them, Gore “acknowledged that some of what he said was not received as he had intended,” emails say.

The State News asked Gore how he intended the comments to be received. He declined to answer, saying “I don’t remember the statement or context of the statement.” MSU declined to say if Gore faced any consequences following the incident.

WHAT GORE SAID

The comments were made during a meeting between Gore and supervisors of the campus Starbucks and Sparty’s convenience stores. The intended topic was “building a strong community and creating a successful work environment.”

Gore raised the Nassar issue about 20 minutes into the meeting, according to the investigator’s notes, saying “Who’s heard of the Nassar trial?”

“In some way shape or form, we have all been affected,” Gore said, according to the notes. He talked about his neighbor, who was treated by Nassar but, in her case, “this was a legitimate medical procedure,” he said.

Then, Gore told the group: “A very large majority of the women did not understand that it was a medical procedure,” referring to Nassar’s patients, who were repeatedly sexually abused under the guise of medical treatment.

Gore also defended Simon, who had just resigned from MSU’s presidency amid widespread criticism of her handling of Nassar.

“You know that Lou Anna resigned,” Gore said, according to the notes. “Not many people know this, it’s not that she didn’t care, she’s just introverted. She was such a good president, she did so much for this university. She shouldn’t have been forced out, she was unrightfully forced out.”

After that, Gore attempted to open up the discussion, the notes say. He asked the group how “we can combat this in our community?”

It was quiet, the notes say, as Gore “called on a bunch of people and they didn’t really know how to answer the question.”

Then, the student-workers asked him, “What is being done on your level?” Or, as the investigator wrote, “essentially, ‘What are you doing?’”

The upset survivor who reported the incident “didn’t understand why (Gore) was talking about it,” the investigator wrote. “No one asked him to justify Nassar’s actions…”

Administration Reporters Owen McCarthy and Theo Scheer contributed reporting.