Celebrating Black History Black History

D1 • FEBRUARY 15 - 21, 2024 • THE ST. LOUIS AMERICAN

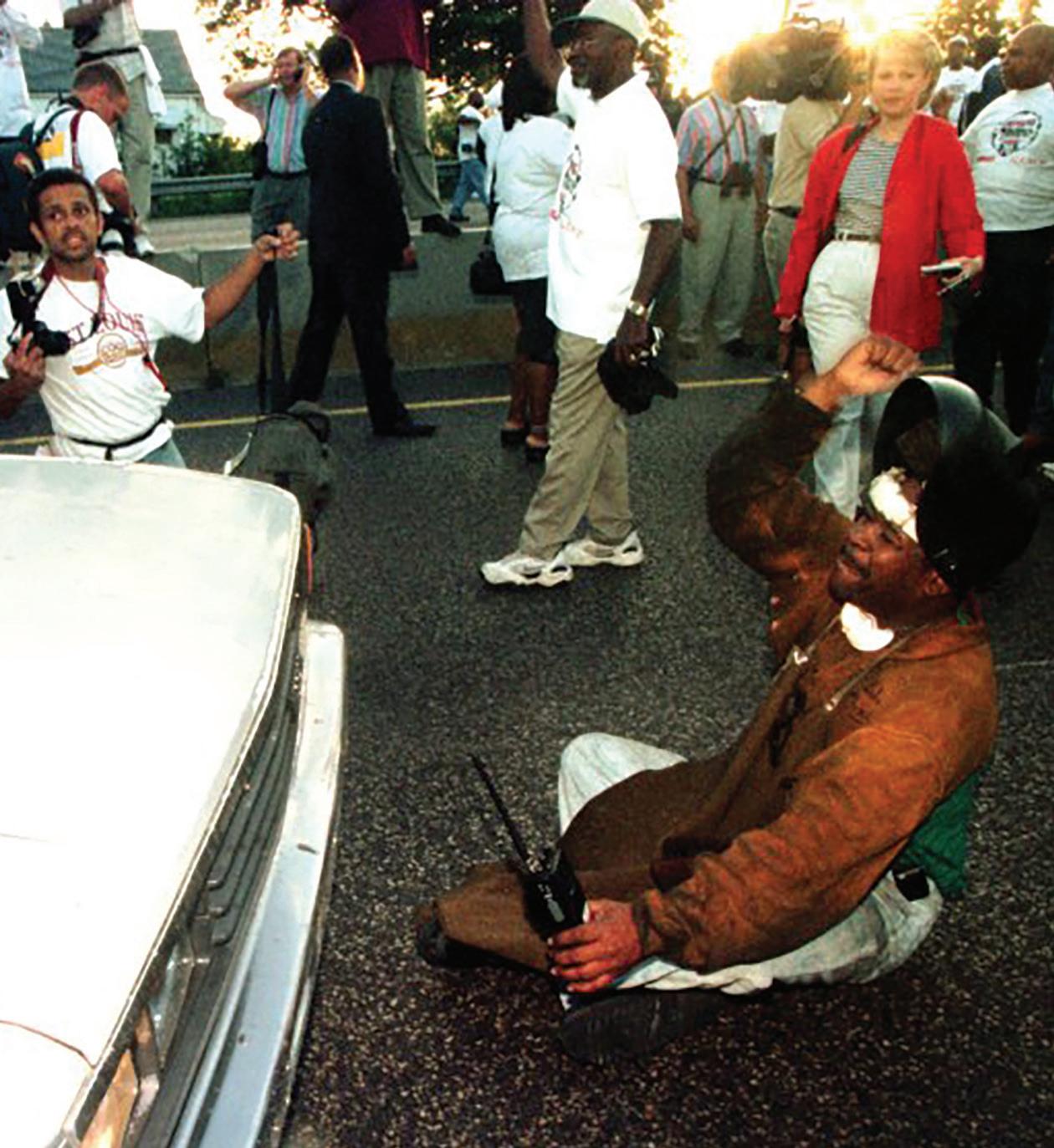

25th Anniversary of the I-70 Shutdown

It led to construction employment opportunities for Black workers

By Sylvester Brown Jr.

St. Louis American

Twenty-five years ago, on July 12, 1999, roughly 300 protestors descended the western ramp off Goodfellow Blvd onto Interstate 70. They gathered in dissent to the Missouri Department of Transportation’s (MoDot) failure to award highway construction contracts to minority firms. This, on a six-mile section of the highway that sliced through some of the poorest and blackest neighborhoods of the city.

The historic event was perfectly planned. Volunteer drivers positioned themselves in front of morning rush hour traffic on the three-lane highway. On cue, they slowed their vehicles, then stopped, which forced cars in the rear to follow suit. That’s when the throng of protesters marched onto the highway, some squatting, some chanting, and some waving handmade signs reading: “No Justice, No Peace!”

U.S. Department of Justice officials estimated there were about 900 people on hand -- many of them onlookers -- but only 250 to 300 stepped onto the highway. Among the celebrity arrestees were activist preacher, Rev. Al Sharpton; the late James Buford; head of the St. Louis Urban League, the late activist attorney, Eric Vickers, the late state Sen. J.B. “Jet” Banks, D-St. Louis; and the late state Rep. Paula Carter (D-St. Louis). Demonstrators were arrested and booked on charges of impeding the flow of traffic and failure to obey a police officer. Most were released within a few hours.

The governor at the time, Mel Carnahan, expressed disappointment with the protest because he believed a deal had been reached that Sunday night, before the planned protest. Spokespersons for two of the major highway construc-

tion firms-KCI Construction Co. and Millstone Bangert Inc.-also expressed surprise, stating that they, too, believed a deal had been reached. Eddie Hasan, then president and CEO of MO-KAN (Construction Contractors Assistance Center), said the sticking point for an agreement was the contractor’s reluctance to agree to a demand that at least 25 percent of the work force be minority.

“This project going right through the middle of North St. Louis symbolizes just how left out we are,” Hasan told Take Five Magazine that month in 1999. “It’s

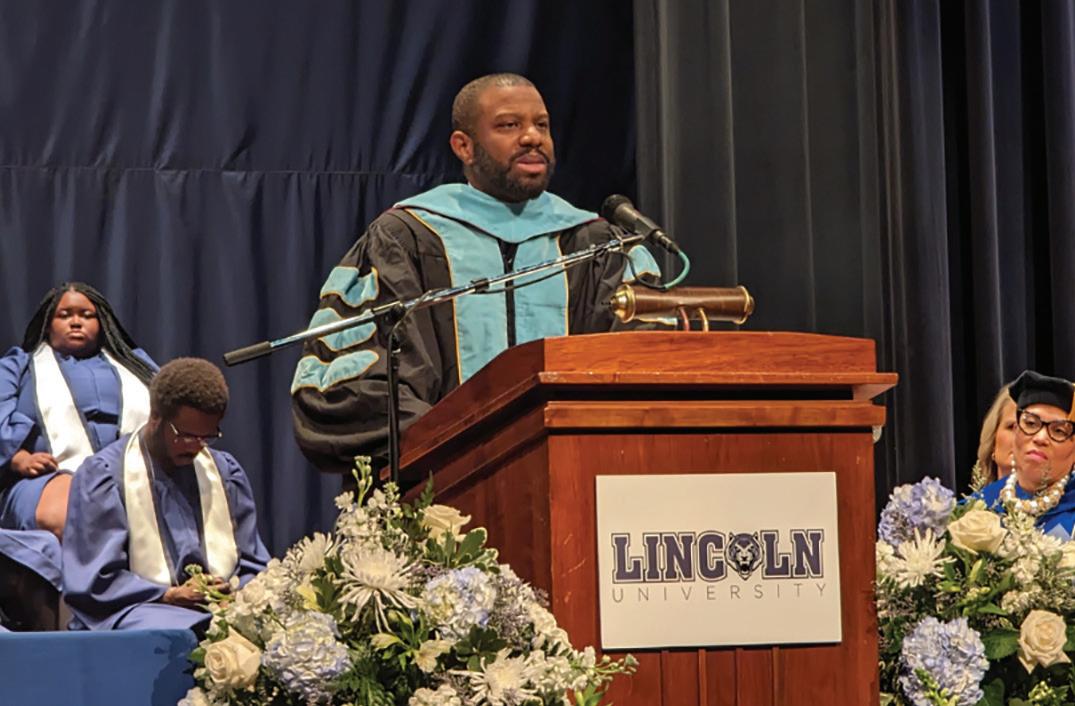

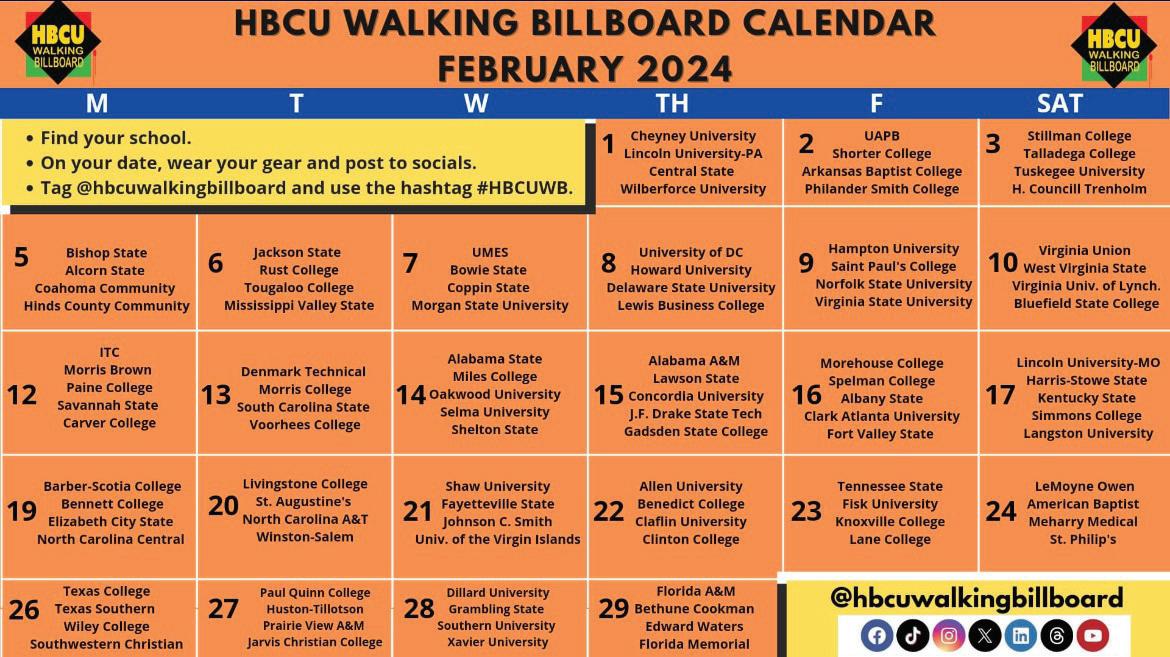

Lincoln University celebrates

Day

St. Louis American

Lincoln University of Missouri (LU) celebrated 158 years of education during the 2024 Founders’ Day celebration in Mitchell Auditorium on Thursday, Feb. 8.

The annual event honors and recognizes the enlisted Black men and white officers of the 62nd and 65th Colored Infantries — who fought and sacrificed

to secure the right to education for freed Blacks following the Civil War.

Dr. Ivory Toldson, national director of Education Innovation and Research for the NAACP and former executive director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities, delivered the keynote

a stretch of intersection where Black men, women and children are living and languishing on both sides of the highway, yet White men are making all the money. It’s time for us to stand up as men and demand that our people also make $20 to $30 an hour.”

Speaking at a rally days after the protest, St. Louis Comptroller Darlene Green echoed Hasan’s sentiments: “Anytime you drive through the city and see construction, but you don’t see African Americans working, you should be upset. It (certainly) upsets me.”

A protester sits in front of a car, during a sit down on Highway 70 in St. Louis, during the morning rush hour traffic, July 13, 1999. Minority contractors and supporters turned out to shut the highway down, saying that the way the state of Missouri grants minority contracts is not fair. More than 100 people were arrested while the highway was shut down for about an hour.

Federal law required at least 10 percent minority participation on the project. State highway officials, at the time, estimated that 14 percent of the construction budget was going to minority firms. Hasan said MO-KAN was demanding that 25 percent of the contract dollars go to minority firms and 35 percent of the construction jobs go to minorities.

The shutdown not only led to increased minority participation on the highway project, but it also served as the catalyst

See Shut Down, D5

during Lincoln University’s Founders’ Day 2024 celebration.

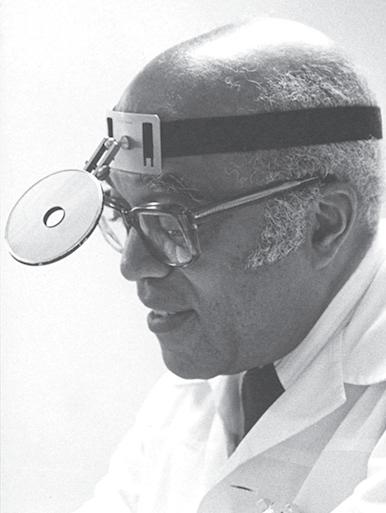

A man of many healthcare firsts

Dr. John H. Gladney crafted historic career at Homer G. Phillips Hospital

Marissanne Lewis-Thompson

St. Louis Public Radio

Dr. John H. Gladney opened his private practice in 1957, becoming the first Black ear, nose and throat specialist in St. Louis. He was later hired as the first Black doctor in the country to head a department of otolaryngology, holding the post at St.

Louis University School of Medicine. In his field, he’s known for his research efforts making the link between hearing loss and diabetes. That work led to his induction into the American Triological Society in 1962 as its first Black fellow. Gladney died in 2011 at age 89. His medical legacy and dedication to the St.

Dr. John H. Gladney

Louis region is now the center of a new Missouri Historical Society collection. St. Louis Public Radio’s Marissanne Lewis-Thompson spoke with Gwen Moore, the curator of urban landscape and community identity at the Missouri Historical Society, about the collection and how Gladney became a key figure in medical history.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Marissanne Lewis-Thompson: Who was Dr. John H. Gladney?

Gwen Moore: Dr. John H. Gladney was an ear, nose and throat specialist. He was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. Dr. Gladney said his mother died when he was [6] years old. That had a profound impact on him. He remembers visiting her in this segregated hospital where Black people were assigned to the basement, and it was obviously substandard. He

See Gladney, D4

Photo courtesy of News-Tribune

Dr. Ivory Toldson, national director of Education Innovation and Research

the NAACP and former executive director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities, delivered the keynote address

Photo by William Greenblatt / St. Louis American

The Black history of the Pan-African flag

Inspired by Marcus Garvey

National Public Radio

The Pan-African flag, which is also called the Marcus Garvey, UNIA, Afro American or Black Liberation flag, is raised ceremoniously each year in St. Louis on Feb. 1 – the first day of Black History Month.

Mayor Tishaura Jones was joined by members of the St. Louis African American Aldermanic Conference and civic leaders as the flag was hoisted on the St. Louis City Hall grounds at Market Street adjacent to 13th Street in Washington Square Park.

The distinctive banner was originally designed to represent people of the African Diaspora, and, as one scholar put it, to symbolize “Black freedom, simple.”

The flag, with its horizontal red, black and green stripes, was adopted by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) at a conference in New York City in 1920.

For several years leading up to that point, Garvey, the UNIA’s leader, talked about the need for a Black liberation flag according to Robert Hill,

a historian and Marcus Garvey scholar.

“The fact that the Black race did not have a flag was considered by Garvey, and he said this, a mark of the political impotence of the Black race,” Hill told National Public Radio.

“And so, acquiring a flag would be proof that the Black race had politically come of age.”

The goal of Garvey’s movement was to establish

a political home for Black people in Africa. Hill says that Garvey patterned his thinking on other nationalist movements at that time — the Jewish Zionist movement, the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and the fight against imperialism in China.

It was the Irish struggle for independence that Hill says “unofficially gave Garvey a lot of the political vocabulary of his movement.”

The Pan-African flag’s colors each have symbolic meaning.

Red stood for blood — both the blood shed by Africans who died in their fight for liberation, and the shared blood of the African people. Black represented, well, Black people. And green was a symbol of growth and the natural fertility of Africa.

Garvey and the UNIA

framed the need for a flag in a political context, Hill explains.

“Everybody immediately seeing that flag would recognize that this is a manifestation of Black aspirations, Black resistance to oppression,” he said.

The creation of a flag was a step for Black people around the world to claim an identity. Michael Hanchard,

a professor of Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, says that flags are important because they symbolize the union of governance, people and territory.

For Black people, the flag means “that they have some way of identifying themselves in the world. And... to also project to those people who are not members of this particular national community that they too belong, that they have membership in a world of communities, a world of nations.”

Hill adds that the PanAfrican flag went on to become the template for flags all over Africa as they gained independence.

Ghana, Libya, Malawi, Kenya and many other African countries adopted the red, black and green — often with the addition of gold, which sometimes symbolizes mineral wealth.

In 2014, after unarmed Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, many peaceful protesters wielded the Pan-African flag.

Hanchard says it makes sense that the flag would be used during a collective crisis:

“So obviously in a moment of clear tragedy and senseless violence ... the need for common cause, becomes a battle cry of sorts.”

Celebrating Black History

We all have a history. A story. We bring with us life experiences that shape who we are and make us better.

At Spire, we know our individual stories only make us stronger as a whole. That’s why we’re committed to an inclusive work environment where all that makes us unique is embraced, encouraged and valued.

Because it truly takes all of us — our backgrounds, our perspectives and our experiences — to move forward.

Photo by Wiley Price / St. Louis American

Mayor Tishaura Jones was joined by members of the St. Louis African American Aldermanic Conference and civic leaders in honoring the Pan-African flag on February 1, the first day of Black History month, before it was raised on a flagpole on the St. Louis City Hall grounds.

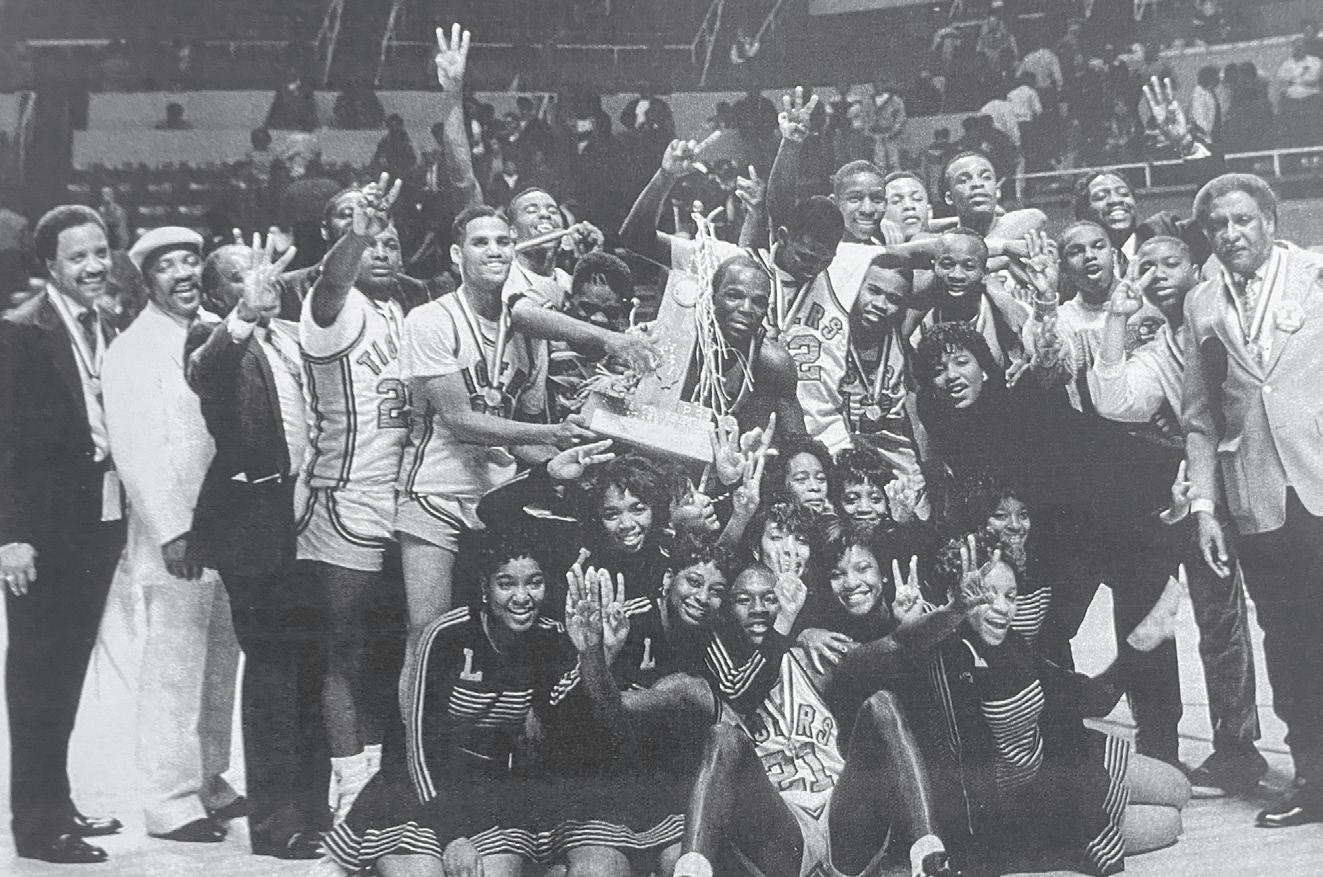

Celebrating East St. Louis Lincoln’s historic three-peat

By Earl Austin Jr. St. Louis American

During my nearly 40 years of covering high school basketball in the St. Louis area, I was usually covering the state basketball championships in Missouri during the month of March.

There was only one occasion where I had the opportunity to cover the Illinois State basketball championships in person. I was assigned to cover the 1989 IHSA Class AA state tournament in Champaign at the University of Illinois.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that I was about to embark on the most exciting and exhilarating weekend of high school basketball in my career as a sports media member. It’s a career that spans five decades, so I’ve seen a lot. I witnessed history as the Lincoln Tigers won the state championship and became the first three-peat state championship team in the state of Illinois.

It’s the 35th anniversary of that great championship run from that great Lincoln team. It was also an improbable run to many because the Tigers entered the season without their great All-American forward LaPhonso Ellis in the lineup.

The 6’9” Ellis had led the Tigers to back-to-back state championships in 1987 and 1988 en route to becoming a McDonald’s All-American and one of the top players in the country. He was starting his career at Notre Dame.

Despite the graduation of Ellis, the Tigers still fielded a formidable lineup and they were able to battle their way back to Champaign for a shot at a three-peat. The new leader was Cuonzo Martin, a 6’6” junior forward with a quiet disposition, yet became a dominant force when he stepped on the court. He averaged 20 points and 10

rebounds while playing the top of the Tigers’ feared full-court press.

The Tigers also had two very talented 6’3” shooting guards in senior Vincent Jackson and junior Chris McKinney. Both were explosive and skilled offensive players who can create a bucket at any time. The point guard was senior Rico Sylvester, a steady hand who distributed the basketball and played good defense. He can also make a big shot when needed. The fifth starter was 6’8” senior Ronald Willis, who was an All-State track athlete in the shot put. The sixth man was 6’4” forward Sharif Ford, who filled in a lot of different roles. Patrolling the sidelines was Hall of Fame coach Bennie Lewis, who was always the cool customer.

Although Lincoln arrived in Champaign for the Elite Eight as the two-time defending state championships, there was respect, but not a lot of hype around them. Especially without Ellis this time around.

Much of the hype was centered around Chicago King ,a powerhouse team from the powerful Chicago Public League. Most figured that they would

take the crown away from Lincoln. The Chicago media members had all but crowned King as the new state champions before a game was even played. Also in the field was Peoria Central, who came to Champaign with an undefeated record. The field was loaded. Lincoln’s task was tall.

Lincoln’s first opponent in the quarterfinals was a talented East Aurora team, who was led by star forward Thomas Wyatt. In the closing seconds, the score was tied 70-70 and East Aurora was holding the ball for one shot to win the game. As the seconds ran down, I thought to myself that Lincoln’s great run may end in the first game.

That was when Martin stole a pass on the baseline and threw the ball down court to a sprinting Sharif Ford, who caught the ball and in one motion flipped it into the basket at the buzzer to give the Tigers a stunning 72-70 victory. The Tigers sprinted off the floor and into the locker room in jubilation. Martin, Jackson and McKinney combined to score 60 of Lincoln’s 72 points.

Next on the docket was a Saturday afternoon showdown with King, who won the state

The

with two free throws with 29 seconds left in the third overtime, it looked like we were headed for a fourth extra session. The Tigers held the ball for the final shot and the ball ended up in the hands of Jackson.

Jackson dribbled the ball between his legs and let fly with a jumper from the top of the key that swished through the net to give Lincoln a 59-57 victory and its historic third state championship in a row.

File Photo

title in 1986 and was eager to take back its place at the top of Illinois hoops. The Jaguars were led by All-American guard Jamie Brandon, who scored 31 points. However, the Tigers held strong and pulled out a 60-57 victory, much to the disbelief of my friends from the Northern part of the state. Martin led the Tigers with 22 points.

The Tigers were one game away from history, but standing in their way was an incredible Peoria Central team that was undefeated and ranked No. 1 in the state. They were led by All-State guard Chris Reynolds, who was headed to Indiana the following season.

What unfolded over the next couple of hours was pure drama and excitement. I still call it the best high school game that I’ve seen in my career. The two teams traded big shots and big plays throughout the evening without backing down one bit. The score was tied at the end of regulation, the first overtime and the second overtime. I remember Rico Sylvester hitting a huge 3-point shot to give Lincoln a 57-55 lead with about a minute left in the third overtime.

When Reynolds countered

As a young 24-year old reporter that was still fairly new to the game, I was overcome with emotion when Jackson’s shot went through the net. I jumped up in my seat and started screaming. “OH MY GOD! THEY DID IT! THEY DID IT! THEY REALLY DID IT!!!

The first person I got to interview after the game was Martin and he had one simple message to everyone around the state that doubted the Tigers and thought that they couldn’t bring home another state title.

“How you like us now?”

Cuonzo pretty much summed up everything with those few words. What I witnessed during that weekend in Champaign was not only does the community of East St. Louis produce stellar athletes, but the competitive will and spirit of those kids is unmatched; and that has been true in all of their sports. On the state’s biggest stage, the Tigers won three high-pressure games by a total of seven points, including two walk off buzzer-beaters. It was amazing to watch.

The three-peat championship was the crowning achievement for Lewis, who had also led the Tigers to a state title in 1982. For his achievements, Lewis was voted the Coach of the 20th Century in the state of Illinois by the Chicago Tribune.

address.

Toldson recognized the day as bittersweet, as the university celebrates its founding with great pride at a time of grieving, following the recent passing of Dr. Antoinette “Bonnie” Candia-Bailey. Toldson acknowledged her dedication and influence as he began his remarks.

“Lincoln University isn’t just an institution,”

Dr. Toldson says.

“It’s a living embodiment of a legacy. A space

where whispers of the past ignite fires of the present, propelling us towards a future brimming with possibility.”

Toldson drew upon ancestral stories as he reminded the students, faculty, staff and alumni to honor the sacrifices and struggles of those who came before.

“Lincoln University stands as a testament to the enduring spirit of Black excellence,” he says.

“Ancestral sacrifices pave the way for our steps and our unwavering belief that education is the key to liberation, illuminating the pathway ahead.”

“(HBCUs) are sanctuaries of hope, incubators of

leaders and testaments to the transformative power of education. HBCUs serve as models for civil rights and compassion. Our campuses foster inclusivity, nurturing minds across diverse backgrounds, forging pathways forward for a more just and equitable society. Students who walk these halls not only hold intellectual prowess but also an innate understanding of the human condition. They graduate to become leaders in science, arts, humanities — armed not just with knowledge but with empathy, a cornerstone of true compassion.”

In addition to Toldson’s address, Lincoln hon-

ored its founders with performances from the Lincoln University Band and Lincoln University choir, the annual laying of the wreath ceremony and by recognizing LU’s Family of the Year, the Coachman family. Earl and Billie Coachman have been married for 57 years, and their story began at Lincoln when they met in 1967. They are part of a strong history of Blue Tiger graduates. Billie’s grandfather, Reginald Robinson, and mother, Frances Regina Robinson, received degrees from Lincoln, and Earl and Billie’s son, Royce, also attended Lincoln.

Dr. Stevie Lawrence

II, the acting president of Lincoln University, expressed gratitude for the dream of education that Lincoln’s founders believed in.

“They never met any of us, but they believed in us.” He says the education at Lincoln today is far greater than what any of the founders could have imagined.

“Our founders (the men of the 62nd and 65th Colored Infantries) entrusted us with this university at this point and time,” Dr. Lawrence says.

“Even as we face some of the darkest days, we must continue to fight for the fundamental ideas of this university so that the mark

we leave behind makes it better for generations to come.” Lawrence is serving as acting president with John B. Moseley on voluntary paid administrative leave. Lincoln’s board of curators is conducting a review after Candia-Bailey accused him of “bullying” and being insensitive to her mental health concerns. Candia-Bailey’s family has confirmed that she took her own life days after being fired by the university.

When he graduated from Meharry, he came to Homer G. Phillips. Homer G. Phillips was this beacon where a lot of Black doctors and other medical professionals, nurses, got

said that›s when he really, at even age 6, got this interest in medicine just from seeing his mother waste away like that in those circumstances. So, he graduated from high school in Little Rock. [He] went on to an HBCU, Talladega [College] in Alabama. From there he went to Meharry [Medical College].

their training. He was not just a practicing physician. He was also a researcher. He did research that really saw a connection between diabetes and hearing loss. Because of that, he became the first Black fellow that was inducted into the American [Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological] Society. And that’s like the premiere society

for ear, nose and throat specialists in the country. So, it was quite an honor.

Lewis-Thompson: Why is it important for more people to know about Dr. Gladney’s legacy?

Moore: He helps us to tell the story of Homer G. Phillips. It tells us multiple stories related to the city›s history and the larger history of Black medicine. You cannot tell a story about Black medicine nationally or internationally without mentioning Homer G. Phillips and these pioneering doctors that helped to bring attention to this city and to Black medicine.

Lewis-Thompson: What led to him becoming the first Black doctor to lead a department of otolaryngology in the U.S.? That’s a pretty big deal.

Moore: He was a practicing physician of course. But he was also a researcher. The fact that he

did this research and was looking into the causes, seeing that link between diabetes and hearing loss, he was unusual in that field. I think what’s really interesting about his story, when you think about somebody like Dr. Gladney, there were many doctors like that that were practicing at Homer G. Phillips Hospital. They came to St. Louis because of Homer G. Phillips Hospital. They started private practices because they were drawn here by Homer G. Phillips Hospital. And so, he was one of those really prominent physicians among many prominent physicians that came here to practice. So, I’m not surprised that he was the first African American to do that because we had so much Black talent.

Lewis-Thompson: Why was Dr. Gladney influential in the St. Louis region?

Moore: He was very engaged in his communi-

ty. The fact that he was interested in helping young Black students. We talk about how he influenced young Black doctors on a university level. But think about how he influenced young Black children in elementary schools where he went there and talked to them, and read to them and interacted with them. And he let them know about his success as a physician. That may sound a little trite, but it is true that he saw his calling as beyond medicine. And he used his skills and his talents as a doctor and his influence and his prominence to really try to elevate others.

Lewis-Thompson: How did this collection come to be? What’s in it?

Moore: His daughter Constance Gladney Agard was the initial contact. So, we got his medical tools. We got some of his yearbooks and photographs. ... We got papers and documents.

Join your SLSO and the inimitable IN UNISON Chorus for this one-of-akind celebration of Black History Month, featuring Grammy- and NAACP Image Award-winning vocalist BeBe Winans. IN

Shut Down

Continued from D1

for the opening of the Construction Prep Center (CPC) which was funded by MoDot and the Federal Highway Administration. The construction trade school, located in Wellston, offered 9-week courses in work readiness and orientation to construction – with an emphasis on heavy highway construction. The school closed in 2014 reportedly due to a lack of funding.

Long before the I-70 shutdown, St. Louis had already established a template for Black, bold and creative protests. In 1942, more than 400 people marched to Carter Carburetor Corp., on North Grand Boulevard, which made artillery-shell fuses and carburetors for military vehicles-demanding more jobs for blacks at defense plants. The protests predated President Harry Truman’s 1948 Executive Order mandating the desegregation of the U.S. military.

Twenty-one years later, in 1963, Blacks launched lengthy protests and sit-ins at Jefferson Bank & Trust Co.- which had many black customers but only two black employees. Led by CORE (Committee of Racial Equality) the weeks-long demonstrations and arrests ended with the once defiant bank agreeing to hire 20 black clerks. Other local white-owned companies soon followed suit.

One year later, in 1964, during the construction of the Gateway Arch, Percy Green, founder of the Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes (ACTION), scaled 125 feet up the north leg of the unfinished Arch to focus attention on the racially exclusive nature of the city’s building trades. Ensuing protests led to a U.S. Justice Department suit (under the newly implemented 1964 Civil Rights Act) against the St. Louis AFL-CIO Building & Construction Trades Council, and four of its member unions.

Other infamous St. Louis demonstrations targeted local utility companies and McDonnell Aircraft Corporation over noncompliance with the Civil Rights Act and major demonstrations (between 1976 and 1984) against powerful political efforts to consolidate, and eventually close, Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

Arguably though, it was the 1999 I-70 shutdown that helped launch the modern civil-rights mode of protests and public activism. The 2014 police shooting of 18-yearold Michael Brown by Ferguson policeman Darren Wilson, lit a fuse that ignited protests that eventually spread across the country and inspired the “Black Lives Matter” movement.

Three years later, in 2017, taking a page from the 1999 shutdown, protestors briefly closed the east-

bound lanes of Interstate 64 at Kingshighway. The demonstrations and arrests followed the acquittal of former St. Louis police officer Jason Stockley who was acquitted for the 2011 shooting of 24-year-old Anthony Lamar Smith, a black man, after a car chase. Creative in their endeavors, demonstrations targeted the Central West End neighborhood of then Mayor Lyda Krewson; blocked a road to a shopping center in Des Peres; marched through the Saint Louis Galleria in Richmond Heights; showed up at a Busch Stadium baseball

game unfurling a banner that read: “Stop Killing Us” and converged on the AFL-CIO convention in downtown St. Louis.

Indeed, St. Louis can boast of a proud, powerful, trend-setting legacy of civil unrest in response to civil, economic and police abuses and injustices. However, it was the I-70 shutdown, 25 years ago, that added a modern-day, in-your-face, stop-thetraffic, twist to America’s Black Civil rights demonstrations.

Sylvester Brown Jr. is the Deaconess Foundation Community Advocacy Fellow.

Brendan Slocumb

Amplifying artists of every age.

Black History Month 2024

Free Movie Screening

Saturday, February 24 | 1 p.m.

Hi-Pointe Theatre (doors open at 12:15 p.m.)

Cinema St. Louis and AARP in St. Louis is proud to present a free screening of Bike Vessel Bike Vessel follows a father and son, 35 and 70, as they cycle from St. Louis to Chicago. Film director Eric D. Seals’ father almost died after three open-heart surgeries. However, 20 years later, he makes a miraculous health recovery after discovering his love for bicycling, bringing his son Eric along with him.

Following the screening, we will have a Q&A session with Donnie and Eric Seals moderated by Emmett Williams, Director, Festival Curation and Education.

Register at: aarp.org/stlouis

Photo by Wiley Price / St. Louis American

Eric Vickers (right) along with Eddie Hasan and Jamilah Nasheed at a news conference about the lack of minority inclusion in construction projects in the region.

Supported

the Edward Chase Garvey Memorial Foundation