Asthma and Environmental Health St. Louis County, Missouri, 2016 – 2020

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that is caused by inflammation and narrowing of the airways, which carry air into and out of the lungs.1 It affects people of all ages, but usually begins in childhood. People with asthma experience recurrent wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, and nighttime or early morning coughing. Symptoms can occur when the airways react to certain exposures, also called triggers. Common triggers of asthma symptoms include tobacco smoke, air pollution, chemicals or dust in the workplace, allergens from dust, animal fur, cockroaches, mold, or pollen, viral respiratory infections like cold or the flu, fragrances, and physical activity.2 An asthma exacerbation, or asthma “attack,” happens when symptoms become more intense, or many occur at the same time. Severe asthma attacks can require emergency care or even be life-threatening.

From 2016 to 2020, chronic lower respiratory diseases (CLRD) were the sixth leading cause of death in St. Louis County.3 In 2021, there were 22.6 CLRD deaths per 100,000 population with deaths due to asthma accounting for fewer than four percent of all CLRD deaths. Asthma does not account for a large proportion of deaths due to CLRD; rather, the burden of asthma in St. Louis County is most apparent when looking at emergency department (ED) discharges. Overall, there were 63.5 ED discharges due to asthma per 10,000 population in 2019, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all CLRD ED visits that year.

Key findings:

• From 2016 to 2020, there were a total of 25,864 ED discharges for asthma. Annual totals ranged from 5,839 to 5,185 until 2020 when asthma ED discharges decreased to 3,320.

• The age-adjusted rate of asthma ED discharges decreased by 44.6 percent from 64.8 per 10,000 in 2016 to 35.9 per 10,000 in 2020. A similar trend in ED discharges for all causes occurred in 2020, reflecting a large decrease in usage of ED services most likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

• Since 2016, annual pollen counts have decreased by 62.6 percent, driven by declines among all species of pollen detected in the county.

• On average, ED utilization to treat asthma was highest during April and May in the spring, and during September and October in the fall. Springtime increases in asthma ED discharges corresponded with elevated pollen levels and tree pollen season.

• Air quality improved since 2016, with the annual number of “Good” AQI days increased and ozone exceedances decreased.

• Geographically, age-adjusted asthma ED discharge rates were highest in the inner north county sub-region, followed by the outer north. The two sub-regions had a greater proportion of houses built before 1960 and a higher percentage of renter-occupied housing units. The inner north, along with the central sub-region, had a higher percent of the population living near busy roads.

Since 2016, ED discharges for asthma demonstrated a downward trend. Age-adjusted ED discharge rates decreased by nearly 45 percent from 2016 to 2020 (See Figure 1). The largest single-year decrease occurred in 2020, with rates dropping 38 percent compared to 2019. Prior to 2020, asthma ED discharge rates decreased ten percent since 2016. In this same five-year period, female county residents had a higher average rate of asthma ED discharges compared to males. Males had higher ED visit rates until 2018, however, when the rate for females surpassed males. Rates for both males and females remained similar and followed the same year-over-year patterns, except for in 2017 when the rate for males increased while the rate for females decreased.

• Asthma ED discharge rates were highest in 2017 at 65.3 per 10,000 population, and lowest in 2020 at 35.9 per 10,000 population.

• The decrease in asthma ED discharge rates in 2020 was likely a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and is reflective of an overall decrease in ED discharges which occurred that year. The lowest rate for the years excluding 2020 occurred in 2019 at 57.9 per 10,000 population.

• In 2018, asthma ED discharge rates were highest for females at 64.3 per 10,000 population, and lowest in 2020 at 36.3 per 10,000 population. Excluding 2020, rates for females were lowest in 2019, with 58.6 ED discharges per 10,000 population.

• In 2017, asthma ED discharge rates were highest for males at 68.2 per 10,000 population, and lowest in 2020 at 35.2 per 10,000 population. Excluding 2020, rates for males were lowest in 2019 at 56.6 per 10,000 population.

Rates of asthma ED discharges were highest in zip codes located in north St. Louis County, particularly in the inner north sub-region of the county, whereas rates were lowest in the west county sub-region (See Map 1). Second-highest rates were observed in the outer north, followed by central and south sub-regions.

• Zip code 63105 had the lowest rate with an average of 8.1 per 10,000 population.

• The zip codes with the lowest rates were 63105, 63005, 63040, 63131, and 63017. All zip codes were in the west and central county sub-regions.

• Zip code 63133 had the highest rate with an average of 188.9 per 10,000 population.

• The zip codes with the highest rates were 63133, 63136, 63138, 63140, and 63134. Each of these zip codes were in the inner north and outer north county sub-regions.

Aeroallergens

For people with allergic asthma, which is asthma that is caused by allergens, exposure to airborne pollen or mold may induce asthma symptoms.

Pollen is an important part of the reproductive process for many trees and other flowering plants. Airborne pollen often comes from trees, grasses, and weeds, which produce small powdery granules of pollen that are easily blown in the wind. Flower pollen consists of waxy granules that are heavier and often require animals or insects, such as bees, for transport.4 As a result, pollen from trees, grasses, and weeds contribute to allergic reactions rather than pollen from flowers.

From 2016 to 2022, the five most common species of pollen detected were mulberry, oak, cedar or juniper, grass, and ash. Each of these pollen species, except for grass, are considered tree pollens. During this period, annual pollen grain counts declined by more than 60 percent, with decreases observed across all pollen species (See Figure 2).

Of the top five pollen species, oak and ash decreased the most with annual pollen counts for both tree species decreasing by approximately 85 percent. Ash trees populations were dramatically reduced due to infestations of emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle known to kill ash trees. Emerald ash borer have been detected in St. Louis County since 2015.5 Loss of oak trees has been observed in Missouri and may be due to multiple causes, including older tree age, environmental stressors such as drought or air pollution, and oak tree diseases or insects.6

• The highest annual pollen count in recent years occurred in 2017, with 54,920.7 pollen grains counted. The lowest annual pollen count was in 2022, with 20,307.7 grains counted.

• Mulberry was the most prevalent pollen species in 2016, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2022. In 2017, the most prevalent pollen species was juniper or cedar. In 2019, the most prevalent pollen species was oak.

Pollen is significant because exposure among sensitized individuals causes inflammation in the upper and lower airways, resulting in worsened asthma symptoms.7 Tree pollen is known to increase the risk of an asthma attack, even on days when trees pollen levels are low.8 Evidence suggests that tree pollen accounts for a disproportionate amount of asthma ED visits each year. An estimated 25,000 to 50,000 people visit the ED for a tree pollen-related asthma attack each year, whereas fewer than 10,000 annual visits may be attributable to grass pollen.9

Pollen season generally lasts from February into September, with tree pollen season beginning first ( See Figure 3). Juniper or cedar was the first pollen season to begin each year, generally starting in February and lasting into March or April. The earliest juniper or cedar pollen season started was in 2017 on Jan. 12, whereas the latest was in 2021 on Mar. 8. Each year, tree pollen season ended in May, with season end dates ranging from May 15 to May 29. On average, tree pollen season lasted about 100 days. The longest tree pollen season was in 2017, lasting 123 days, whereas the shortest tree pollen season was in 2021 at 81 days.

In recent years, grass pollen season started in May. The earliest grass pollen season started, however, was in 2017 on Apr. 26 and the latest was May 13 in 2022. Grass pollen season end dates were more consistent, ranging from May 31 to Jun. 4. The average grass season lasted approximately 27 days, with seasons ranging from 36 days in 2016 and 2017 to 18 days in 2022.

Weed pollen start and end dates were less consistent. Weed pollen season start dates ranged from May 31 in 2018 to Jul. 26 in 2022. End dates ranged from Jun. 26 in 2020 to Sep. 20 in 2016 and 2018. Annual duration of weed pollen season was similarly variable. From 2016 to 2018, weed pollen season lasted about 100 days. Since then, the duration of weed pollen season has decreased substantially to as low as one day in 2021.

Starting in February, daily pollen counts increased until they reached a peak in April or May (See Figure 4). Pollen counts were highest in April, with a mean daily count of more than 680 pollen grains. The month with the second highest average daily pollen count was May with an average of 302 pollen grains per day. Daily pollen counts reached lowest levels in the winter months, with average counts of less than five in January, November, and December.

Mold is another common allergen known to worsen, or even cause, asthma symptoms. Among people with asthma who are sensitized to mold, those with multiple mold reactions were more likely to be admitted to the hospital for severe asthma attacks and were more likely be hospitalized multiple times due to asthma.10 Exposure to mold during infancy and childhood may increase the risk of developing asthma.11-14

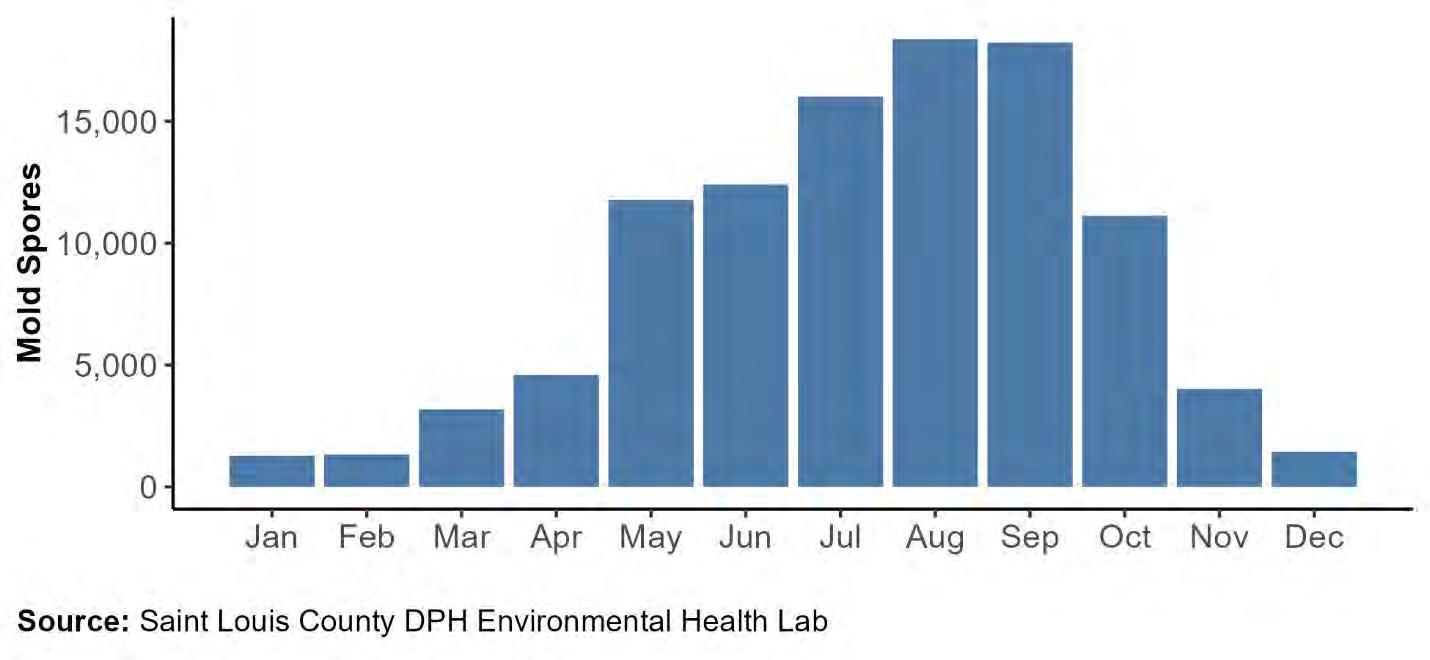

Mold spore counts increased each month until reaching a peak late summer, usually in August or September (See Figure 5). Daily mold counts were at highest levels each year from July through September, with averages exceeding 16,000 mold spores. The month with the highest daily mold count was September 2020 with an average of nearly 25,000 mold spores. Conversely, daily mold counts were lowest throughout the winter, with average counts below 2,000 from December through February. The months with the lowest observed mold count was January 2016 and January 2022, with average daily counts of 530 mold spores.

Trends in asthma ED discharges follow a seasonal pattern (See Figure 6). Daily visits to the ED generally peaked in April and May during the spring and in September, October, and November during the fall. Asthma ED discharges were lowest in June and July and lower than average from December through February.

Annual increases in the spring correspond with the tree pollen season and annual peaks in daily pollen counts, with both reaching peak levels during April and May. The relationship between daily mold counts and seasonal trends in asthma ED discharges, however, was less clear. Daily mold counts reached high levels in July when asthma ED discharges were at their lowest levels.

• From 2016 to 2020, there was an average of 17.4 ED discharges for asthma per day.

• April 2017 had the highest daily average of 29.1 discharges per day with nearly six more visits per day higher than the second highest daily average of 23.5 in April 2019.

• Out of the years included in this analysis, April had the highest average number of daily discharges in 2016, 2017, and 2019. In 2018, May had the highest average number of discharges.

• In 2020, average daily discharges were highest in February. The total number of ED discharges, including for asthma, plummeted in March of 2020.

• The month with the lowest number of daily ED discharges was July 2019, with an average of 10.7 visits per day.

• From 2016 to 2019, July consistently had the lowest number of average discharges. In 2020, both May and August had the lowest daily discharges with an average of 6.8 ED discharges per day.

Air Quality

Air pollution is another environmental exposure that can exacerbate asthma symptoms. There are five criteria pollutants: Ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. Exposure to these pollutants worsens asthma symptoms and decrease lung function.15 Daily air quality is reported using Air Quality Index (AQI) values. Higher AQI values correspond with greater levels of air pollution and poorer air quality. These values are divided into six color-coded levels, ranging from “Good” to “Hazardous” (See Table 1). When daily AQI exceeds 51, people with asthma may be at increased risk of an asthma attack.16

Table

201 to 300

301 to 500

From 2016 to 2021, most days had “Good” AQI values, with the number of “Good” days increasing overall (See Figure 7). Meanwhile, the number of days categorized as “Moderate” or “Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups” decreased during this period. There were no days with AQI values exceeding the threshold for “Unhealthy.”

Ozone Exceedances

One common source of air pollution is ozone. Ozone is a gas that naturally exists in our atmosphere, occurring in the upper atmosphere and at ground level. In the upper atmosphere, most ozone exists in the stratosphere, referred to as the “ozone layer.”17 While the ozone layer is an important component of the atmosphere that protects the Earth by absorbing radiation from the sun, ground level ozone presents a greater threat to health.

High levels of ozone can cause irritation in the lungs and airways, resulting in cough, sore throat, and chest tightness, wheezing, or shortness of breath.19 For people with asthma and other respiratory illnesses, ozone worsens airway inflammation. As a result, high ozone levels may reduce lung function, induce asthma attacks, and increase the need for asthma medications and utilization of health care services.19

Ground level ozone is caused by chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOX) and volatile organic compounds (VOC) that are facilitated by light and heat.18 Common sources of NOx and VOC pollution include cars, industrial facilities, and power plants. Ozone is most likely to reach high levels during the summer months when heat and sunlight react with NOx and VOC in the air.

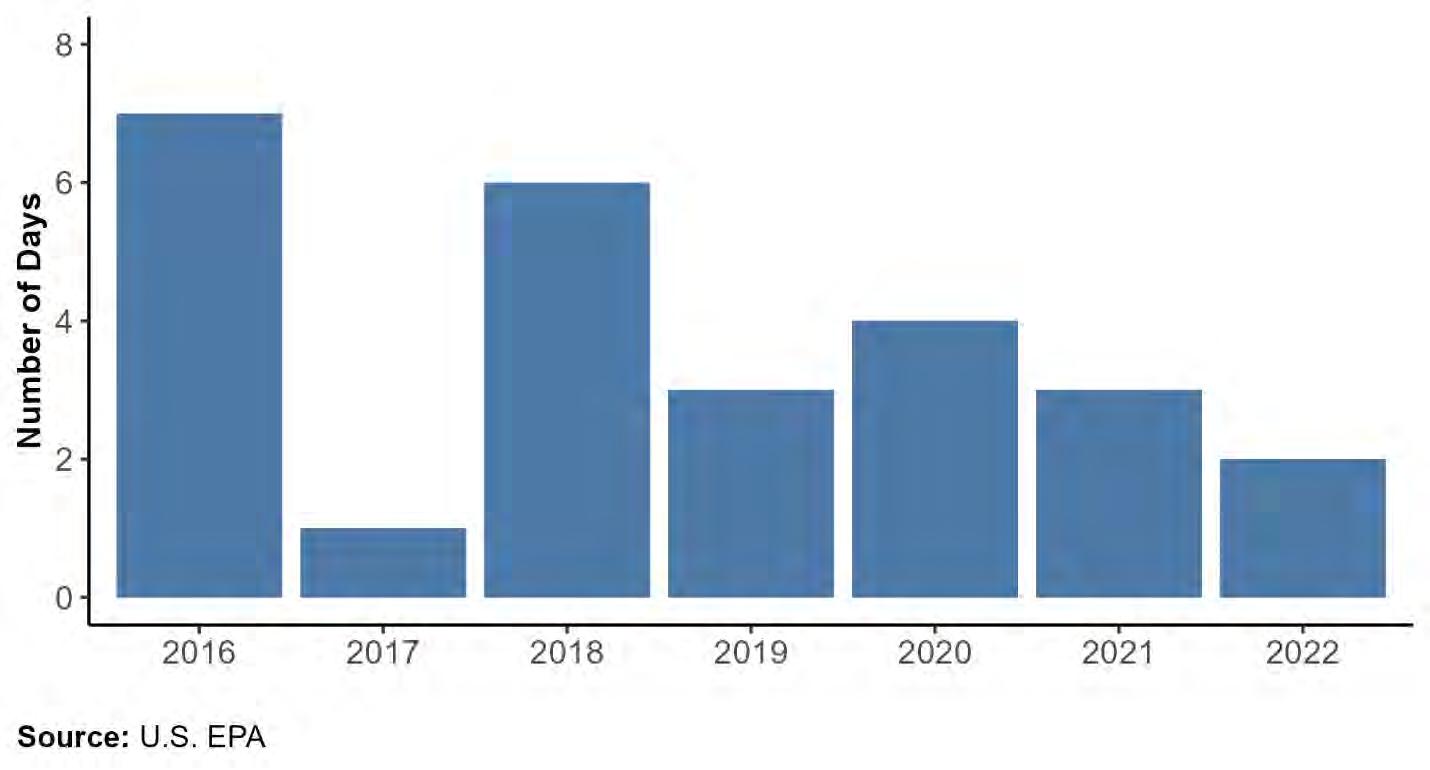

Ground level ozone may combine with other pollutants to create smog. Ground-level ozone concentrations are monitored during the ozone season each year from Mar. 1 until Oct. 31. Ozone exceedances occur when the ozone level surpasses the standard of 70 parts per billion (ppb) averaged over eight hours. The number of annual ozone exceedances in St. Louis County decreased since 2016 (See Figure 8).

• There was a total of 25 recorded ozone exceedances in St. Louis County from 2016 to 2022.

• Ozone exceedances were highest in 2016, with seven days having ozone levels higher than 70 ppb. 2017 saw the fewest number with only one exceedance recorded.

• Most ozone exceedances during this period occurred in June and July. There was a total of nine exceedances recorded in June and 11 in July.

• From 2016 to 2022, there were no ozone exceedances recorded in March, April, or October.

Particulate Matter

Particulate matter refers to small particles, including small solids and liquid droplets, that are found in the air. These particles originate from multiple sources such as construction sites, smoke from forest fires or wood stoves, and emissions from industrial facilities or cars. There are two types of particle pollutants: Inhalable particles (PM10), which are 10 micrometers (µm) or smaller, and fine inhalable particles (PM2.5), which are 2.5 µm or smaller.

Particles that are smaller than 10 µm pose the greatest threat because when inhaled, they can enter the lungs and bloodstream. As a result, exposure to particulate pollution has been linked to increased risk of mortality due to cardiopulmonary disease and lung cancer.20 In addition, exposure to both PM2.5 and PM10 is known to exacerbate symptoms of asthma and increase the risk of an asthma attack, particularly among children. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 may also induce the development of asthma in children and reduce lung function in adults.21-22

Traffic-Related Air Pollution

Vehicle emissions are a common source of air pollution, particularly in urban areas. Major pollutants caused by cars and other vehicles include carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, particulate matter, VOCs, and oxides, with the latter two being key ingredients in the creation of ozone. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution is a risk factor for the development of asthma in children, accounting for as much as 18 to 42 percent of asthma cases.15, 23-24

• The central sub-region had the greatest proportion of residents living near high traffic roads, followed by the inner north sub-region with 18.3 and 17.0 percent of their populations living within 300 meters of a busy road, respectively.

• The west sub-region had the smallest percentage near busy roads at 10.2 percent.

• Approximately 13 percent of residents lived near a busy road in both the outer north and south sub-regions.

Indoor Exposures

Keeping a clean home environment free of asthma triggers is important to prevent asthma attacks. Common triggers inside the home include tobacco smoke, dust, cockroaches and other pests, pet dander, nitrogen dioxide from gas stoves or burning wood, and mold.2 Secondhand smoke and nitrogen dioxide, for example, are both known to increase the risk that children will develop asthma. Secondhand smoke also reduces lung function, contributing to asthma attacks and increased utilization of healthcare services.15

Presence of mold in the home, such visible mold or mold odors, may increase the risk of developing asthma among children and exacerbate respiratory symptoms among those with asthma.11, 13-14 Common species of indoor mold include Cladosporium, Penicillium, and Aspergillus, all of which are associated with asthma symptoms, including persistent cough and wheeze.12, 14, 25 Mold will grow where there is moisture. Accordingly, indoor mold often occurs in places with water leaks, condensation, or flooding. Buildings and homes that are older are more likely to have mold.26 Older homes are more likely to have less energy efficient designs with poorer ventilation and insulation, thereby increasing indoor moisture and risk of mold growth.27

• The central sub - region has the greatest proportion of older houses, with more than three in ten houses built prior to 1940. One - third of the houses in this region were built from 1940 to 1959. Approximately 16 percent were built from 1960 to 1979, 11 perce nt from 1980 to 1999, and 8 percent since 2000.

• In the inner north sub-region, nearly half of the houses were built from 1940 to 1959 and another 27 percent were built from 1960 to 1979. About 15 percent of houses were built prior to 1940, six percent from 1980 to 1999, and four percent since 2000.

• Most houses in the outer north sub-region were built from 1960 to 1979. Twenty percent of houses were built from 1940 to 1959 and from 1980 to 1999, respectively. Only about two percent of houses were built before 1940 and five percent were built after 2000.

• In the south sub-region, almost four in ten houses were built from 1960 to 1979, and about one quarter were built from 1940 to 1959 and from 1980 to 1999, respectively. Five percent of houses were built in 1939 or earlier and less than 10 percent were built since 2000.

• The west sub-region has the greatest proportion of new houses, with about 37 percent of houses built from 1960 to 1979 and from 1980 to 1999, respectively. Another 12 percent of houses were built since 2000. Less than three percent of houses were built before 1940 and nine percent were built from 1940 to 1959.

Children with asthma are more likely to live in homes with triggers such as secondhand smoke, mold or other moisture problems, and pests compared to children without asthma. These triggers are more prevalent in renter-occupied households, likely contributing to a higher percentage of children with asthma living in renter-occupied housing units.28 Since renters have less control of their living environment compared to homeowners, they also face greater challenges in eliminating asthma triggers from their home environment.

• Zip code 63034 had the smallest percentage of renter-occupied housing units at 6.3 percent.

• The zip codes with the smallest percent of renter-occupied units were 63034, 63131, 63038, 63005, and 63025.

• Zip code 63140 had the greatest percentage of renter-occupied units at 81.4 percent.

• The zip codes with the highest percent of renter-occupied units were 63140, 63133, 63143, 63136, and 63120.

Most homes, however, do contain some level of indoor allergen exposure, regardless of homeownership status or income.29 Considering the amount of time spent indoors and at home,30 removing indoor triggers is necessary to manage asthma symptoms. Moreover, the most effective way to create a healthy home environment for people with asthma is to remove all asthma triggers from inside the home. Home visit programs, where trained visitors work with families to remove triggers from the home and provide resources to help manage asthma symptoms, are one strategy that is effective at reducing exposure to asthma triggers.

The Saint Louis County Department of Public Health (DPH) offers home visiting programs intended to address asthma triggers in the home:

Saint Louis County DPH Healthy Homes Program

Through the Healthy Homes Program, residents can receive free in-home assessments on their environment to identify potential asthma triggers. Trainings and educational sessions about asthma management are also available for parents and caregivers. The program addresses other environmental hazards like mold, lead, allergens, carbon monoxide, home safety, and pesticides. In addition to reducing asthma triggers, Healthy Homes promotes lead poisoning prevention and home safety. As part of the efforts, we offer the following:

• Individual family consultation services on asthma management methods to help control indoor environmental asthma triggers,

• In-home environmental assessments to identify what can be done to reduce asthma triggers and provide other resources to improve the home health environment, and

• Group trainings and education for parents and caregivers.

For more information about the Healthy Homes Program services or to schedule a home visit, please call 314-615-5323 or visit: www.KnowAsthmaSTL.com

Show-Me Missouri Healthy Homes Program

In partnership with Children’s Mercy Kansas City (CMKC), DPH is implementing the Show-Me Missouri Healthy Homes Program (SMMHHP), a multi-year project funded through U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Healthy Homes Production grant. Through SMMHHP, DPH will administer $1.8 million to provide community trainings, healthy homes assessments and interventions to address health and safety hazards in 135 residential homes in two major communities in Missouri.

In St. Louis County, the program target area includes the Promise Zone (PZ), a federally designated area spanning eight zip codes and 27 municipalities. DPH program staff will work with families through home assessments and interventions to help identify asthma triggers, focusing on the eight Healthy Home Principles: Keeping homes clean, dry, pest-free, contaminant-free, safe, ventilated, comfortable, and maintained. In addition, each program participant’s home will be tested for radon.

The goals of the program are to:

1. Improve the health and safety of families through implementation of a home assessment and remediation program in targeted communities.

2. Increase the number of professionals in the St. Louis County and Kansas City areas with knowledge of healthy home issues through the Building Performance Institute (BPI) courses.

3. Improve the knowledge of safe and healthy home issues for residents of St. Louis County and Kansas City communities through structured education and outreach workshops.

Methods

ED discharge records were obtained from the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, of Health Care Analysis & Data Dissemination for the years 2016 to 2020. ED discharges were classified using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) underlying cause codes–chronic lower respiratory disease (CLRD) ICD-10 codes J40-J47 and asthma ICD-10 codes J45.

The data received captures all ED discharges (within or outside of St. Louis County, Missouri) of St. Louis County, Missouri residents. The American Community Survey (ACS) was used to generate 5-year estimates for the St. Louis County, Missouri population by age, gender, race, and Hispanic origin for 2016-2020. Population-based rates (calculated using the number of events–ED discharges or deaths–divided by the estimated population size for the same demographic group and year) reflect the overall burden on the general population. The overall percent of residents living below the federal poverty level for each census tract was also obtained from ACS using the 5-year estimate for 2016 to 2020.

In the analysis, neighborhood poverty level was assigned to each ED discharge based on residents within each St. Louis County, Missouri 2010 census tract for the years 2016 to 2019 and 2020 census tract for the year 2020. Each census tract was assigned one of four categories of percent below federal poverty level: Low (0 to <10 percent); Medium (10 to <20 percent); High (20 to <30 percent); and Very high (30 to 100 percent).32 Age-adjusted and age-specific rates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated in R version 4.1 using population estimates from ACS. The rates were age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. population.33 Geographic regions were determined from St. Louis County Planning division region maps by assigning each tract a matching region. Maps were generated using R version 4.1 for rates by zip code and geographic region.

Annual aeroallergen data reports were obtained from the Saint Louis County Department of Public Health, Environmental Health lab for the years 2016 to 2022. Reports included daily counts by respective pollen and mold species for each year. Pollen and mold are collected using a Burkard slit-type volumetric spore trap, which captures airborne pollen and mold samples continuously over a 24-hour period. Samples are processed and counted by the Environmental Health Lab. Subsequent counts of pollen grains or mold spores are used to calculate the number of particles per cubic meter of air sample.

Pollen season was defined as the period in which pollen counts exceeded or were equal to 50 grains per cubic meter for each respective pollen species.34 Start dates were the first day each calendar year with pollen grain counts exceeding this threshold; end dates were the last day each calendar year with pollen grain counts exceeding this threshold.

Local Resources for Asthma

Saint Louis County DPH Environmental Health Lab, Pollen and Mold Center

The Environmental Health Laboratories has published daily pollen and mold count reports since 1960. These reports include the official area pollen and mold readings, which are updated every business day by 11 a.m.

For pollen and mold count reports, please call (314) 615-6825 or visit: https://stlouiscountymo.gov/services/pollen-and-mold/

In addition, the Environmental Health Lab provides tape lift testing for St. Louis County residents for a fee. This test can be used to identify mold on indoor surfaces. For more information about tape lift testing, please call (314) 615-8524.

Clinical Services

Through the Public Health Nursing Program, DPH clinic clients can receive free home visits from a registered nurse to help them better understand and manage their disease. Nurses work with children, adults, and families to ensure that the disease process is clear, medications are understood and being used as prescribed, and lost time from school and work is minimized.

If you are a DPH clinic client and would like to request an asthma home visit, please call (314) 615-6994.

Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America – St. Louis Chapter

The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America – St. Louis Chapter provides resources in the St. Louis community, including access to medications, equipment, and education for uninsured and underinsured children.

For more information, please visit: https://aafastl.org/

St. Louis Children’s Hospital Healthy Kids Express – Asthma Program

The Health Kids Express program provides education and resources for children and families and assists local doctors and school nurses to care for children with asthma.

For more information, please visit: https://www.stlouischildrens.org/health-resources/advocacyoutreach/healthy-kids-express/healthy-kids-express-asthma-program

Missouri Tobacco Quitline

The Missouri Tobacco Quitline is free to Missouri residents that want help to quit using nicotine products. Coordinated by the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, program participants may receive a free “quit kit” and access to a quit coach to help you plan your quit.

To register for services, please call 1-800-QUIT-NOW or visit: http://www.quitnow.net/Missouri

For teens (ages 13-17), Live Vape Free is a resource to learn more about vaping and get support to quit via interactive videos, podcasts, and live chats with a quit coach. To register for Live Vape Free Teen, please text VAPEFREEMO to 873373.

Suggested Citation

Hutti, E, Kelsey, D, Adams, C, Sandbothe, O, Weis, R, & Wang, E. Asthma and Environmental Health, St. Louis County, Missouri, 2016-2020. Chronic Disease Epidemiology (CDE) Program Profile No. 14. St. Louis County, MO: Department of Public Health. February 2023.

Chronic Disease Epidemiology Program

The Chronic Disease Epidemiology (CDE) program is responsible for analysis, interpretation, and presentation of health data related to chronic diseases and their risk factors. The CDE program supports DPH by providing the following services:

• Develop study designs, questionnaires, and case definitions.

• Evaluate chronic disease programs.

• Locate or develop surveillance systems and analyze epidemiologic data sets.

• Provide county, state, and national comparison data.

• Interpret St. Louis County chronic disease and risk factor data.

• Conduct epidemiologic investigations and special studies of chronic diseases and chronic disease risk factors of public health importance.

• Monitor St. Louis County chronic disease trends.

• Provide scientific advice and technical assistance to community groups and outside partners with respect to surveillance and other epidemiology data expertise.

• Publish reports and web pages on chronic disease and risk factors.

For more information about the CDE program please contact us at: chronicdisease.doh@stlouiscountymo.gov

References

1. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2022, March). What Is Asthma? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma

2. U.S. EPA. (2022, April). Asthma Triggers: Gain Control. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.

https://www.epa.gov/asthma/asthma-triggers-gain-control

3. Tutlam, N.T., Kelsey, D., Hutti, E., Adams, C., & Wang, E. (2021, October). Leading Causes of Death Profile (Report No. 13). Saint Louis County Department of Public Health Chronic Disease Epidemiology Program. https://stlouiscountymo.gov/st-louis-county-departments/publichealth/health-data-and-statistics/chronic-disease-reports/leading-causes-of-death/

4. U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Plant Pollination Strategies. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/Plant_Strategies/index.shtml

5. Zarlenga, D. (2015, September 14). MDC: Emerald ash borer now confirmed in St. Louis County. Missouri Department of Conservation. https://mdc.mo.gov/newsroom/mdc-emerald-ash-borernow-confirmed-st-louis-county

6. Missouri Department of Conservation. (n.d.). Oak Decline in Missouri. https://mdc.mo.gov/trees-plants/diseases-pests/oak-decline-missouri

7. Idrose, N.S., Walters, E.H., Zhang, J., Vicendese, D., Newbigin, E.J., Douglass, J.A., Erbas, B., Lowe, A.J., Perret, J.L., Lodge, C.J., & Dharmage, S.C. (2021). Outdoor pollen-related changes in lung function and markers of airway inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 51(6), 636-653. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.13842

8. De Roos, A.J., Kenyon, C.C., Zhao, Y., Moore, K., Melly, S., Hubbard, R.A., Henrickson, S.E., Forrest, C.B., Diez Roux, A.V., Maltenfort, M., & Schinasi, L.H. (2020). Ambient daily pollen levels in association with asthma exacerbation among children in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Environment International, 145 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106138

9. Neumann, J.E., Anenberg, S.C., Weinberger, K.R., Amend, M., Gulati, S., Crimmins, A., Roman, H., Fann, N., & Kinney, P.L. (2018). Estimates of present and future asthma emergency department visits associated with exposure to oak, birch, and grass pollen in the United States. GeoHealth, 3(1), 11-27. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GH000153

10. O’Driscoll, B.R., Hopkinson, L.C., & Denning, D.W. (2005). Mold sensitization is common amongst patients with severe asthma requiring multiple hospital admissions. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, 5(4), https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-5-4

11. Jaakkola, J.J.K., Hwang, B.F., & Jaakkola, N. (2005). Home dampness and molds, parental atopy, and asthma in childhood: A six-year population-based cohort study. Children’s Health, 113(3), 357-361. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7242

12. Gent, J.F., Kezik, J.M., Hill, M.E., Tsai, E., Li, D.W., & Leaderer, B.P. (2012). Household mold and dust allergens: Exposure, sensitization and childhood asthma morbidity. Environmental Research, 118, 86-93.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2012.07.005

13. Iossifova, Y.Y., Reponen, T, Ryan, P.H., Khuranan Hershey, G.K., Villareal, M., & LeMasters, G. (2009). Mold exposure during infancy as a predictor of potential asthma development. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 102(2), 131-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S10811206(10)60243-8

14. Reponen, T., Lockey, J., Bernstein, D.I., Grinshpun, S.A., Villareal, M., & LeMasters, G. (2012). Infant origins of childhood asthma associated with specific molds. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 130(3), 639-644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.030

15. Tiotiu, A.I., Novakova, P., Nedeva, D., Chong-Neto, H.J., Novakova, S., Steiropoulous, P., & Kowal, K. (2020). Impact of air pollution on asthma outcomes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6212. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph17176212

16. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. (2015, October). Air Pollution. https://aafa.org/asthma/asthma-triggers-causes/air-pollution-smogasthma/#:~:text=When%20the%20AQI%20is%20101,about%20high%20air%20pollution%20days

17. U.S. EPA. (2021, October). Basic Ozone Layer Science. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. https://www.epa.gov/ozone-layer-protection/basic-ozone-layer-science

18. U.S. EPA. (2022, June). Ground-level Ozone Basics. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. https://www.epa.gov/ground-level-ozone-pollution/ground-level-ozonebasics

19. U.S. EPA. (2022, August). Health Effects of Ozone in the General Population. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C. https://www.epa.gov/ozone-pollution-and-your-patientshealth/health-effects-ozone-general-population

20. Dockery, D.W., Pope, C.A., Xu, X., Spengler, J.D., Ware, J.H., Fay, M.E., Ferris, B.G., & Speizer, F.E. (1993). An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. New England Journal of Medicine, 329, 1753-1759. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejm199312093292401

21. U.S. EPA. (2022). Supplement to the 2019 Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.

https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/isa/recordisplay.cfm?deid=354490

22. Keet, C.A., Keller, J.P., & Peng, R.D. (2017). Long-term coarse particulate matter exposure is associated with asthma among children in Medicaid. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 197(6), 737-746. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201706-1267OC

23. Eguiluz-Gracia, I., Mathioudakis, A.G., Bartel, S., Vijverberg, S.J.H., Fuertes, E., Comberiati, P., Cai, Y.S., Tomazic, P.V., Diamant, Z., Vestbo, J., Galan, C., & Hoffman, B. (2020). The need for clean air: The way air pollution and climate change affect allergic rhinitis and asthma. Allergy, 75(9), 2170-2184. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14177

24. Alotaibi, R., Bechle, M., Marshall, J.D., Ramani, T., Zietsman, J., Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J., & Khreis, H. (2019). Traffic related air pollution and the burden of childhood asthma in the contiguous United States in 2000 and 2010. Environment International, 127, 858-867.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.03.041

25. Gent, J., Ren, P., Belanger, K., Triche, E., Bracken, M.B., Holford, T.R., & Leaderer, B.P. (2002). Level of household mold associated with respiratory symptoms in the first year of life in a cohort at risk for asthma. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(12), 781-786.

https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.021100781

26. Ganesh, B., Scally, C.P., Skopec, L., & Zhu, J. (2017, October). The relationship between housing and asthma among school-age children: Analysis of the 2015 American Housing Survey. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/93881/the-relationshibetween-housing-and-asthma_1.pdf

27. Salo, P.M., Arbes, S.J., Crockett, P.W., Thorne, P.S., Cohn, R.D., & Zeldin, D.C. (2008). Exposure to multiple indoor allergens in U.S. homes and its relationship to asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 121(3), 678-684. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jaci.2007.12.1164

28. Leech, J.A., Nelson, W.C., Burnett, R.T., Aaron, S., & Raizenne, M.E. (2002). It’s about time: A comparison of Canadian and American time-activity patterns. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 12, 427-432. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500244

29. Krieger, J. (2010). Home is where the triggers are: Increasing asthma control by improving the home environment. Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology, 23(2), 139-145.

https://doi.org/10.1089%2Fped.2010.0022

30. Berkowitz, S.E., Traore, C.Y., Singer, D.E., & Atlas, S.J. (2015). Evaluating area-based socioeconomic status indicators for monitoring disparities within health care systems: Results from a primary care network. Health Services Research, 50(2), 398-417.

https://doi.org/10.1111%2F1475-6773.12229

31. Klein, R.J. & Schoenborn, C.A. (2001). Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2000 Stat Notes, 20, 1-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11503781/

32. Lo, F., Bitz, C.M., Battisti, D.S., & Hess, J.J. (2019). Pollen calendars and maps of allergenic pollen in North America. Aerobiologia, 35, 613-633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-019-09601-2

Appendix 1: Emergency Department Discharges

Appendix

Notes:

Source: Missouri DHSS, Patient Abstract System

Case Definition: International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) primary diagnosis codes J45. Rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 US population (not including age group rates)

CI = Confidence Interval

Appendix 1.2 Asthma emergency department discharges by month and year, St. Louis County, 2016 – 2020

Appendix 2: Pollen

Appendix 2.1 Pollen totals by type and year, St. Louis County, 2016 – 2022

Notes:

Source: Saint Louis County Department of Public Health, Environmental Health Lab

Appendix 2.2 Pollen totals by month and year, St. Louis County, 2016 – 2022

Notes:

Source: Saint Louis County Department of Public Health, Environmental Health Lab

Appendix 2.3 Pollen season start and end dates by type and year, St. Louis County, 2016 – 2022

Case Definition: Pollen season start and end dates were the first and last dates of each calendar year that daily pollen counts exceeded or were equal to 50. Four outliers were removed for the purposes of this report: Elm 8/26/2016; Juniper 10/19/2016; Juniper 12/29/2016; and Juniper 11/26/2019.

Appendix 3: Mold

Notes:

Source: Saint Louis County Department of Public Health, Environmental Health Lab