7 minute read

Writing Books

Writing Books that Explain Things

Alex Frith (1991-1996) is a children’s non-fiction author and editor working on staff for Usborne Publishing.

Anyone who studied Classics will be familiar with the idea of sons who strive to earn a better reputation than their parents. Success stories include Achilles becoming more famous than his father Peleus, or Alexander conquering more than his father Phillip could ever imagine. As far as I’m concerned, outdoing my parents simply isn’t an option. I’ve turned to a saying that everyone in the modern age is familiar with: if you can’t beat them, join them.

It took some 5 years of work, but I managed to complete a joint project with both of my parents, a graphic novel – for grown-ups, mind! – called Two Heads (see Pauline Books on page 14). I wrote the script, but the story it tells is about the achievements of Uta and Chris Frith, two leading neuroscientists (my mother is something of a leading expert in autism and dyslexia; my father in schizophrenia and the question of consciousness). Which is to say, all the interesting bits of the book come from their life and work – although I can flatter myself that it’s me who has made the book fun to read and, more crucially, accessible to a general audience. No prior knowledge of brains required!

To an extent, this kind of writing is an extension of the very skills everyone learns at school – it’s like a really big homework project. You’re given a brief, some reading material, and then sent off to write it up before it gets marked. Only in this case, it was being marked by my parents rather than a teacher. Part of the point of homework is to prove to your teacher that you’ve understood whatever topic it is that you’ve just been learning about. So it is with books that explain things. I, as writer, have to be SURE that I’ve understood the topic so that I can, in turn, explain it clearly and simply for readers. When my expertsin-the-field parents read over each new iteration of the script, to give their comments and suggestions, I was very much looking for that friendly tick in the margin…

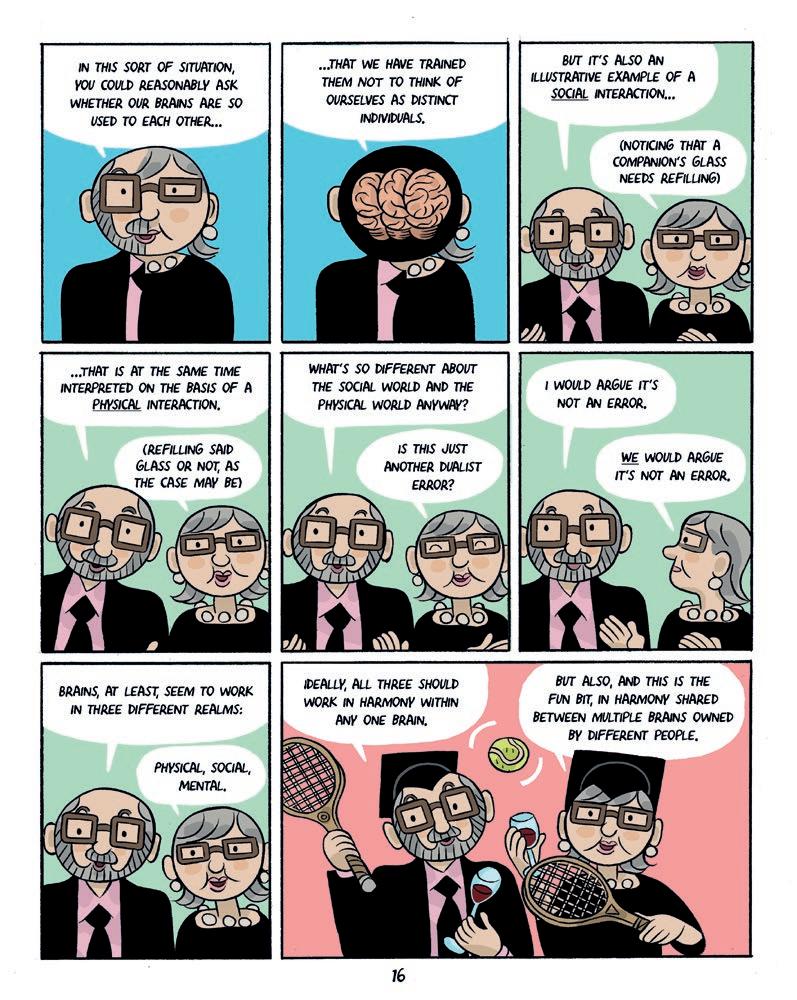

As for contents of Two Heads, it is a little about how brains work, and a lot about how people interact with each other. Why does anyone need to know this? This is going to sound grandiose, but I honestly think understanding even a little about both makes life easier and has the potential to make the world a better place.

Here’s the thing – we literally live inside our brains. We don’t know WHY the way our brains work means that we have minds, and personalities, and likes and loves and all the emotions – but we DO know that we simply cannot exist without them. To know how our brains work is, literally, to understand ourselves better, which in turn makes living life a bit easier. Well, I find it comforting, anyway. The trouble is, even the finest minds in the field don’t claim to truly know how the brain works. We do know a few things, though, and I find them to be surprising and delightful, and hope readers of the book will agree! Even people who already have a basic understanding of neuroscience should get a kick out of seeing visual representations of how neurons do what they do.

But the meat of the book is about social interaction. The fact is, if there is one thing brains are designed to do, it is to interact with other brains. Any of you who have spent prolonged periods on your own, without talking to anyone else, will feel just how true

this is. Yes, it is also true that our brains are like a control and information-relay centre for our bodies, but they’re so much more. Brains are crude telepathy devices that attempt to decipher what other people are thinking and feeling, as well as communication devices that attempt to project our own thoughts and feelings to other people. Only we have to use the blunt tools of language, alongside the more sophisticated tools of empathy, body language and just copying each other a lot.

It is my view, after burying myself in the research and theories presented in the book, that the more we understand what our brains are doing, the better chance we have at learning to get along with one another. Especially when it comes to two key findings. 1) On the whole, people work better in pairs, or teams, than they do working alone. 2) Those pairs and teams get even better results the more varied the people on that team. Varied in EVERY sense – yes, this includes race and gender and sexuality, the hot topics of today – but we humans also thrive on pooling our variation of how we approach problem-solving, or the things we enjoy, and even, to an extent, variation in how clever we are (or aren’t).

‘Teamwork is good’ is exactly the sort of phrase that people throw around as common-sense knowledge. Although it’s also the sort of thing that plenty of people, secretly, do not believe, but merely tolerate as a social idea. This book unpicks some of the scientific research that has gone into attempts to verify – or indeed falsify – this idea. Because real science doesn’t provide simple answers, it pokes around at ideas to try to get to truth slowly and carefully. And in this case, the research is very much ongoing, but the results so far are, I think, optimistic for our future as a human race. And yes, the results DO support the hypothesis that teamwork IS good!

One question that often comes up when talking about the book is, why is it a graphic novel? Partly, in all honesty, it’s because we like comics and think they make the subject more digestible. But there’s something deeper at play, here, too, to do with being better at explaining things. With a normal, no-pictures-type book, a writer would work with an editor and perhaps expert consultants, job done. But for a comic, a writer has to work with an artist as well (there are writer-artists out there, and it’s not a coincidence that a person who can do both often achieves spectacular results). And that means, I’d better be so sure I know what I’m talking about, that I can translate the ideas into pictures as well as words. More than that, I have to be sure that the picture ideas make enough sense to the artist the s/he (in this case, a he) can draw them with the correct nuance to get the idea across. In other words, lots of levels of sense-checking before the book goes live (you know, the sort of checking teachers always tell you to do before you hand in that essay, that no one ever leaves time to actually do…)

I’ve been a comics reader all my life (Tintin, Asterix, the Beano and 2000AD being the most formative influences). If I’ve learned anything, it’s that the artist is king. If you don’t let the artist dictate the flow of a story, it’s going to be either boring or difficult to read. I can’t underestimate how crucial Dan Locke’s contributions to this book were, mostly down to things such as ‘I can’t get that across in just one panel, give me 2!’, or ‘this idea would work really well as a whole page, not a measly panel’. All this adds up to make the book much bigger, and longer to create – but worth it in the end.

To create this book about how collaboration is (nearly) always the best way to do things, we like to think we practised what we were preaching. There were the three writers and the artist, of course, but also several editors, and as with most books helpful family members who offered vital criticisms on what was funny, what was not, what made sense, and what did not. Is the science behind the idea of collaboration sound? As an acolyte of the scientific method, I can only say: read about the research for yourself and make up your own mind.