16 minute read

The School Play

from Feb 1951

by StPetersYork

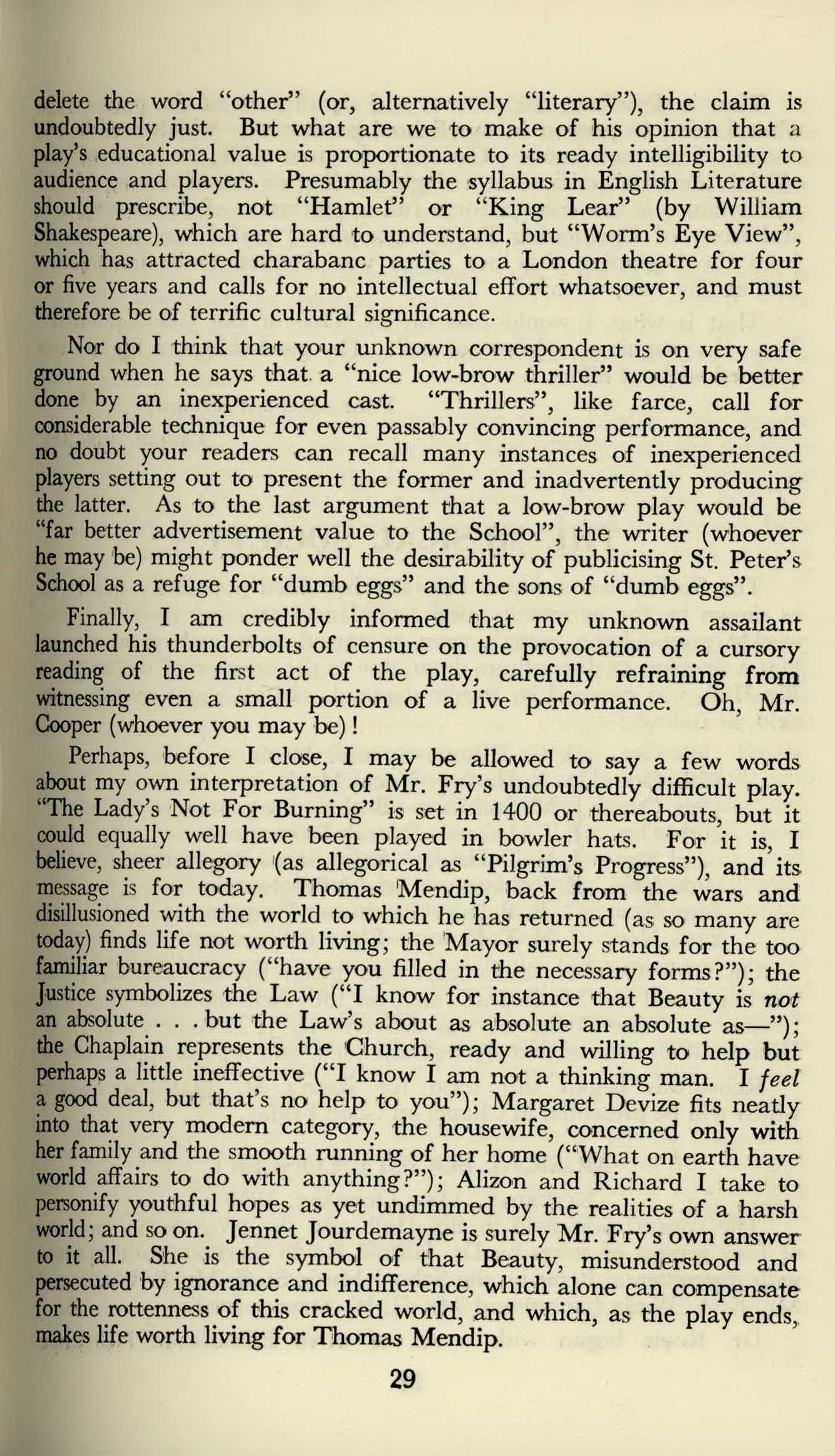

"THE LADY'S NOT FOR BURNING" By Christopher Fry

"In the past I wanted to be hung. It was worth while being hung to be a hero, seeing that life was not really worth living." So said a convict who confessed falsely to a murder, in February, 1947; and, insofar as the story of Christopher Fry's play matters, that is the story. Thomas Mendip tries to get himself hanged for a murder he did not commit, in the small market town of Cool Clary "in 1400 either more or less or exactly". The attempt to achieve notoriety brings Thomas Mendip into the house of the Mayor, and into touch with various members of the Mayor's household; and especially he meets, unexpectedly, Jennet Jourdemayne, who is believed to be a witch, but who is "not for burning". But it is not the story, and certainly not the minor episodes in it, which makes this play so intensely interesting. The author is one of two successful Christian playwrights at present writing for the London theatre, and it is a very long time since that has happened, and his play is written with poetic imagination and with sparkling wit. This play achieved a very considerable success on the London stage, and was received with acclamation on its recent production in New York. The lines are packed with utterly unexpected and poetic metaphors; and the wit is, at times, extremely subtle. Indeed, anyone who wishes to enjoy this play to the full is strongly advised either to read the play first, or else to see it more than once. The play seems better each time one sees it, and there are not many modern plays of which that could be said.

The very merits of Christopher Fry's writing make his play a difficult one to produce and to act. There is little or no dramatic action, and the lines are difficult enough to learn and very difficult to "get across" to an audience. Extremely good diction, exquisite timing, and superb quickness on cues are necessary if the play is to be fully appreciated. But the play was a success, let there be no doubt about that. It was said during rehearsals this year that Mr. Burgess could get talent out of wood. Certainly it was no light task to produce this play with inexperienced actors on so small a stage; and rumour, a lying jade if not a witch, says that a large number of cigarettes were for burning before this excellent result was achieved. But not even Mr. Burgess could have produced this play without a tremendous amount of hard work and co-operation from his players.

The chief responsibility rested on M. E. Kershaw as Thomas Mindip, and he rose to the occasion most admirably. Kershaw made full use of a very nice speaking voice and said his words beautifully : and he used so much larger a compass in his voice than anyone else —with perhaps one exception—either this year or last, that it was a real pleasure to listen to him. This was a really good performance, and he was supported by C. V. Roberts as Jennet Jourdemayne, the 23

witch. This is a very difficult part for a boy to play, and the most striking thing about Robert's acting was the sincerity of his playing. His voice was somewhat monotonous; but, especially in his long scene with Thomas Mendip in Act 2, he held his audience and he was at his best then. It was a courageous and on the whole convincing performance.

P. L. Bardgett played Margaret Devize, the sister of the Mayor and the mother of Nicholas and Humphrey, with real spirit and even gusto. He had a lot of the fussy housewife about him, and his voice and diction, as one might expect from a choral scholar of King's College School, Cambridge, were very good. This was a most promising performance, as was that of A. D. Staines as Nicholas Devize. The outstanding feature of Staines' performance—a truly remarkable first appearance—was his timing, and he seldom missed a point in some excellent lines. As his brother, Humphrey Devize, G. P. Gray was admirably contrasted. He was rather stilted in his movements, but he spoke his lines well and improved considerably in the last performance.

P. H. Webster as Hebble Tyson, the Mayor, gave an impression of a fussy bureaucrat, and yet possibly handicapped himself by using an unnatural note in his normally good speaking voice. The result was that he hardly dared to change the note, and so his interpretation tended to be literally monotonous : but it was a very good effort. D. G. Hilton, a Justice, "as sober as a judge, albeit somewhat on circuit", seemed to enjoy himself thoroughly and communicated a good deal of that enjoyment to the audience. This was quite a good piece of acting. Matthew Skipps, the man Thomas Mendip asserted he had murdered, makes only a very brief appearance towards the end of Act 3, and very nearly steals the whole play. I. G. Cobham, as this somewhat intoxicated rag and bone man, very nearly stole it too. The author has given him some lovely lines, and if on the first night Cobham slightly over-acted the part, he sobered down subsequently, and did his one scene well. C. K. Smith was a very pleasant Chaplain, more perhaps in love with his lyre than with his duties as domestic Chaplain to the Mayor; but that was what the author intended. Richard, the orphaned clerk, found abandoned as a baby by a Priest in a poor box in a church, has no very clearly defined character in the play, and G. W. Riley found it perhaps rather hard going to bring the part to life. Nor does Christopher Fry seem to have endowed Alizon Eliot with any decisive characteristics. She is to marry Humphrey Devize and therefore Nicholas wants her, but she decides on her own for the orphaned clerk. M. I. L. Rice did as much as could be expected in a somewhat colourless role, and looked the part and spoke and moved on the stage in a way suggesting distinct promise when he gets a bit older.

The setting, despising architectural incongruity, was admirable : and Mr. Howat and his team are much to be congratulated : as indeed are all those who laboured behind the scenes.

24

Mr. Waine had composed some very pleasant music for this production—another labour of love. Perhaps it was a little monotonous and something altogther livelier might have been more suitable : but it was tuneful and very pleasing and was admirably played by Mr. Stevens (viola) and J. Ford (flute) and R. B. Atkinson (piano). Where your correspondent was sitting Ford's flute was sometimes almost inaudible and it was a pity he was so masked by the piano : but the balance may well have sounded better elswhere in the Hall.

This production was a success, there can be no doubt about that; and both play and acting were of a higher standard than last year. Having tasted the joys of Christopher Fry, is it too much to hope we may see the same author's "Death of the First Born"—a play about the Exodus—before very long?

C.P.

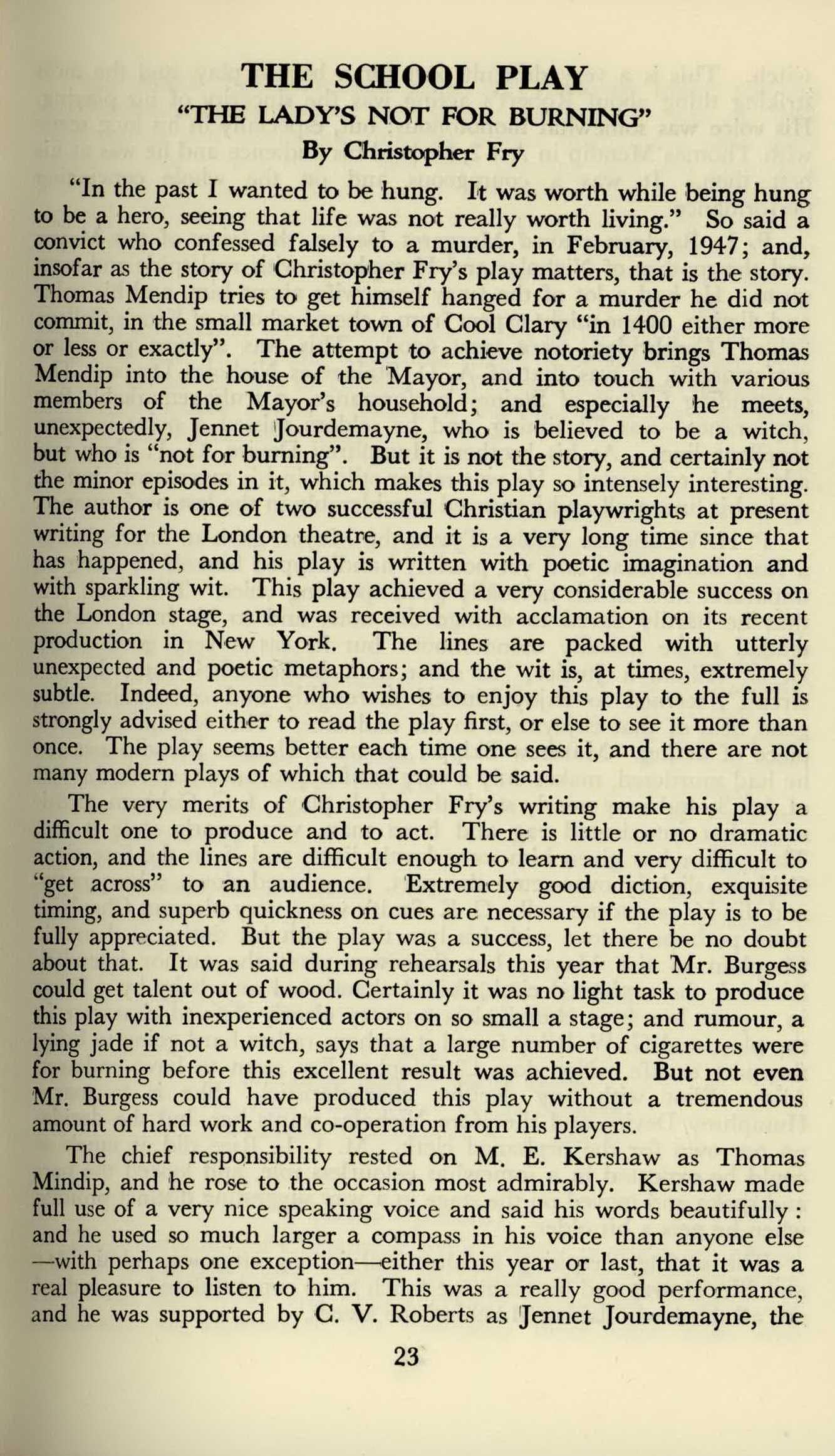

"THE LADY'S NOT FOR BURNING" (14TH, 15TH AND 16TH DECEMBER, 1950)

CHARACTERS (In the order of their appearance) RICHARD, an orphaned clerk ... THOMAS MENDIP, a discharged soldier ...

ALIZON ELIOT

NICHOLAS DEVIZE

MARGARET DEVIZE, mother of Nicholas ... HUMPHREY DEVIZE, brother of Nicholas

HEBBLE TYSON, the Mayor

JENNET JOURDEMAYNE THE CHAPLAIN ...

EDWARD TAPPERCOOM, a Justice

MATTHEW SKIPPS

G. M. M. A. P. G. p. C. C. D. I. W. RILEY

E. KERSHAW

L. RICE G. D. STAINES L. BARDGETT P. GRAY

H. WEBSTER

V. ROBERTS K. SMITH G. HILTON G. COBHAM

SCENE A room in the house of Hebble Tyson, Mayor of the small market town of Cool Clary

TIME 1400, either more or less or exactly

THE PLAY PRODUCED BY LESLIE BURGESS THE SETTING DESIGNED BY A. T. HOWAT

(Some Opinions)

The presentation of Christopher Fry's comedy, of which our official account is printed above, evoked an unusual amount of comment. In general the verdict was preponderantly favourable, to what was admittedly an experiment, but inevitably there were those who 25

criticized the choice on the score of the play's unsuitability and unintelligibleness. In the circumstances the publication of a selection from several letters received may be of interest.

We give first a personal letter received by the Producer from Mr. Norman Hoult, Producer of the York Repertory Company :—

THEATRE ROYAL, YORK. 15th December.

Dear Mr. Burgess,

My most grateful thanks for a most delightful evening, and my sincerest congratulations to yourself, the entire cast, and all concerned on a really splendid and remarkable achievement, of which you may well be proud.

A difficult thing to tackle is "The Lady's not for burning"--but right gallantly was it tackled from the word "go". The setting was excellent (dead right), the pace was there, and the urgency was there. and the quieter passages were given their full value. A particular point which impressed me was the timing : the boys knew where the laughs should come, and come they did—and were never trodden on. I think a special word of praise should go to the "ladies' ! They were splendid and got the real spirit of the play, as, indeed, did all; I loved the enthusiasm and attack.

I do thank and congratulate you and all most heartily and sincerely.

Yours sincerely,

NORMAN HOULT.

Our next is from a visitor, unconnected with the School, to the first performance on the Thursday :— CC . .. The setting was beautifully simple and effective, and the one outstanding virtue was the clear diction of every one of the players. One could hear every word without strain, and many a mumbling professional cast might well have learnt a lesson in their own technique.

Of individual performances, the best was Nicholas. He used his face and had a nice sense of character and comedy. Next, I think, was Jennet, who has a beautiful voice, and used it with meaning. He conveyed beautifully so many undertones of emotion. To me he suggested what The Dark Lady of the Sonnets might have been.

I hope your courage will inspire others to venture beyond the commonplace. . ."

Lastly, to reflect all shades of opinion, we print the following from a correspondent who wishes (reasonably enough) to remain anonymous :—

The Editors of "The Peterite."

ST. PETER'S SCHOOL,

YORK.

14th December, 1950.

Dear Sirs,

It is with trepidation and indignation freely intermingled that I send you my complaint. I hope that you will publish my views (with, of course, all the spelling mistakes corrected). I am a simple, unassuming person, and I want to know why I, and so many other suckers, have to sit through the sort of play which has become a habit of the St. Peter's Players. Last year, we had some specious nonsense, a very bad German play which gained nothing when translated into English. This year we are treated to a jumbled mass of words, the better lines of which had to be cut out owing to their obscenity. I still can't understand what wasn't cut out—and don't much want to.

Now if the play is really terribly clever, and I am just a dumb egg who has got to be educated, there is some excuse for it. But then the audience is composed very largely of dumb eggs like me and I don't believe that one boy in twenty or, dare I suggest it, one master, one fond parent or one friend of the School in twenty understood what it was all about. The play has passed over our heads, and I don't see why we should have to suffer in silence whilst the intelligentsia goes into raptures. Surely it is a waste of everyone's time and energy to produce such a play, and a nice low-brow thriller would be (a) of far more interest to the audience, (b) of far greater educational value since both audience and players would understand what it was all about, (c) far better done by an inexperienced cast, and (d) far better advertisement value for the School.

This is surely a reasonable view even if the play outpoints Bill Shakespeare in every act. In my opinion, however, and I reckon that I am entitled to an opinion as much as any other literary critic, the whole play is suppurating drivel from the word "go". The author has taken in a lot of people who are bigger fools than I. The play is like the futuristic picture made by the haphazard daubings of a donkey's tail, which is said to have been praised by eminent art critics. There just isn't anything to puzzle over and, if the keyword to Julius Caesar is "smile" or 'Macbeth is "sleep", then the keyword to this masterpiece is just—"bolony".

Yours faithfully. ONE OF THE UNENLIGHTENED.

In the light of the direct conflict of opinion revealed in the above correspondence we felt that we should invite the observations of Mr. Burgess on the outspoken strictures contained in the last letter. Mr. Burgess has, of course, for some ten years, produced and been largely responsible for the selection of the School plays. He writes as follows :—

To the Editor of "The Peterite." Dear Sir,

Thank you for permitting me to see the letter from "One of the unenlightened", though I despair at the outset of the task of lightening his darkness—particularly as I understand that the anonymous writer, though giving his address as "St. Peter's School, is not one of the boys. (This should be said in fairness to the boys, who, in general, are at least conscious of their need of enlightenment). It is notoriously impossible to explain to the blind what it is like to see, and therein is the essence of the divergence between your correspondent, who considers "The Lady's Not For Burning" "bolony" (which I take to be a word of disapproval), and myself, who believe that it is one of the comparatively few worth-while modern plays.

I should be inclined to leave it at that, were it not that this letter (by an unknown hand) contains certain misconceptions which are not entirely matters of opinion. Your correspondent (whoever he may be) argues that not one boy in twenty understood what the play was about. Granted, though doubted. But the School Plays are not presented to the boys, except incidentally at the dress rehearsal. They are official occasions when adult audiences of parents and friends are invited to see the best the School can do in the realm of dramatic art. The plays are not intended as diversions for the School any more than are, say, the official performances of the Musical Society. If they were, I should certainly take your unnamed correspondent's advice and prefer "The Ghost Train" to "Macbeth"; and no doubt Mr. Waine would readily relinquish Bach and do his best with songs about Red Nosed Reindeers and Puddy Tats. No, Sir, your correspondent (whoever he is) has got it all wrong. St. Peter's School aspires to some culture, at any rate among its senior boys, and must not be judged by the mentality of the lowest form in St. Olave's. I, myself, am fantastically (and thankfully) ignorant of the world of science; but I shall not therefore demand that the forthcoming School Science Exhibition consist of the simpler conjuring tricks or only of exhibits within the compass of my own meagre understanding. My colleagues will no doubt stage the very latest photo-electric miracles, and, though I shall not understand them, I shall have the grace to admit that, within limits of their own somewhat curious ambitions, they are doing the right thing.

Your correspondent, Sir (whoever he may be), "reckons that he is entitled to an opinion as much as any other literary critic". If we

28

delete the word "other" (or, alternatively "literary"), the claim is undoubtedly just. But what are we to make of his opinion that a play's educational value is proportionate to its ready intelligibility to audience and players. Presumably the syllabus in English Literature should prescribe, not "Hamlet" or "King Lear" (by William Shakespeare), which are hard to understand, but "Worm's Eye View", which has attracted charabanc parties to a London theatre for four or five years and calls for no intellectual effort whatsoever, and must therefore be of terrific cultural significance.

Nor do I think that your unknown correspondent is on very safe ground when he says that. a "nice low-brow thriller" would be better done by an inexperienced cast. "Thrillers", like farce, call for considerable technique for even passably convincing performance, and no doubt your readers can recall many instances of inexperienced players setting out to present the former and inadvertently producing the latter. As to the last argument that a low-brow play would be "far better advertisement value to the School", the writer (whoever he may be) might ponder well the desirability of publicising St. Peter's School as a refuge for "dumb eggs" and the sons of "dumb eggs".

Finally, I am credibly informed that my unknown assailant launched his thunderbolts of censure on the provocation of a cursory reading of the first act of the play, carefully refraining from witnessing even a small portion of a live performance. Oh, Mr. Cooper (whoever you may be) !

Perhaps, before I close, I may be allowed to say a few words about my own interpretation of Mr. Fry's undoubtedly difficult play. "The Lady's Not For Burning" is set in 1400 or thereabouts, but it could equally well have been played in bowler hats. For it is, I believe, sheer allegory (as allegorical as "Pilgrim's Progress"), and its message is for today. Thomas Mendip, back from the wars and disillusioned with the world to which he has returned (as so many are today) finds life not worth living; the Mayor surely stands for the too familiar bureaucracy ("have you filled in the necessary forms?"); the Justice symbolizes the Law ("I know for instance that Beauty is not an absolute . . . but the Law's about as absolute an absolute as—"); the Chaplain represents the Church, ready and willing to help but perhaps a little ineffective ("I know I am not a thinking man. I feel a good deal, but that's no help to you"); Margaret Devize fits neatly into that very modern category, the housewife, concerned only with her family and the smooth running of her home ("What on earth have world affairs to do with anything?"); Alizon and Richard I take to personify youthful hopes as yet undimmed by the realities of a harsh world; and so on. Jennet Jourdemayne is surely Mr. Fry's own answer to it all. She is the symbol of that Beauty, misunderstood and persecuted by ignorance and indifference, which alone can compensate for the rottenness of this cracked world, and which, as the play ends, makes life worth living for Thomas Mendip.

29