7 minute read

"The Knight of the Burning Pestle"

from Feb 1955

by StPetersYork

"What is the play to be this year?" That is the question which greets the producer every year at the beginning of the Christmas Term. Mr. Burgess remains reticent. After all, he does not know the answer himself until he has carefully sifted many possibilities. And when he has made his choice, rather than be drawn into explanation or discussion, he wisely prefers to let the performance speak for itself. Again this year his quiet confidence was justified. The success of "The Knight of the Burning Pestle", greatly enjoyed by juvenile and adult audiences alike, and not least by the players themselves, gave one more proof of that shrewdness in casting and skill in production which we have come to expect of him.

The choice of a play may often resolve itself into the question whether to offer the audience a glimpse of some acknowledged masterpiece at the risk of some inadequacy, particularly among the minor players, or whether to be content with a play of less intrinsic value which is within the compass of the whole cast. That the first course is worth attempting was shown by last year's production of "Macbeth". The second course, however, is more likely to lead to a balanced and finished production. "The Knight of the Burning Pestle" is a dull reading play, but its authors have contrived situations —the coffin scene, the encounter with Barbarossa, the muster of soldiers—which could hardly fail in popular appeal when acted on the stage. It does not pretend to the poetic and dramatic intensity of Shakespearean drama; but its cheerful atmosphere of boisterous burlesque comedy falls more easily within the range of the average schoolboy player. Where there is poetry or subtle characterisation it is so important to strike just the right note. The burlesque spirit is not so exacting and can even survive such accidents as befell Jasper on the final evening, when he nearly lost his trunk hose leaping out of his coffin.

Not only was the play well suited to schoolboy talents, as might be expected in a play originally performed by boy actors, but the roles had been distributed with particular care. So well adapted were they to what each player could do that, though we knew that some were more gifted than others, we were never made painfully aware, as so often happens, that the leading players were being poorly supported. That thread of the play which contains a vein of sentiment was perhaps played a little less convincingly than the rest; but the general standard was good, and the eye was caught not only by the star performers but by the minor player admirably suited to his part. Wright as Michael and Elliott as the Boy were good examples. So shrewd was the casting that at times one reflected with some amusement that the player had only to caricature himself to fill the role to perfection.

Of the principal players both Staines and Moore maintained their reputations. We knew that Staines had the swagger to carry off 37

the part of Ralph; but he also revealed a natural turn for comedy and cleverly introduced into his address to the soldiers a Churchillian lisp which was not lost on the audience. To the part of the Citizen's Wife Moore brought the same intelligence and natural ability that he displayed last year as Lady Macbeth and gave another fine performance. Kirkus danced and spluttered effectively as an indignant father. And Bardgett found the part of the Citizen much more congenial than the one he played last year. His range of expression and gesture seemed vastly extended.

One of the most exacting parts was that of the roistering Merrythought, with his boisterous cheerfulness, his snatches of song i and ne'er a thought for the morrow. The embodiment of a humour I rather than a character it would perhaps require an experienced actor to rescue it from a certain monotony. Yet Atkinson gave a very robust performance and deserves commendation for his verve and vocal talent.

Besides providing a well-balanced cast this production also successfully avoided that other fault which often bedevils amateur performances : sluggishness in the action. Performed without a curtain the play moved briskly and without irritating delays, while the changes of scene rapidly effected before our eyes by high-stepping page-boys who always marched out to the same catchy tune were both effective and amusing.

The set chosen for the play was an approximate reconstruction of an Elizabethan Playhouse based on De Witt's contemporary drawing of the Swan Theatre. The new set-builders, Messrs. Hart and Gaastra, made an impressive debut and we look forward to seeing more of their work next year. The music staff and orchestra also contributed notably to a production which thanks to good team-work and expert direction proved well-balanced and, above all, extremely entertaining.

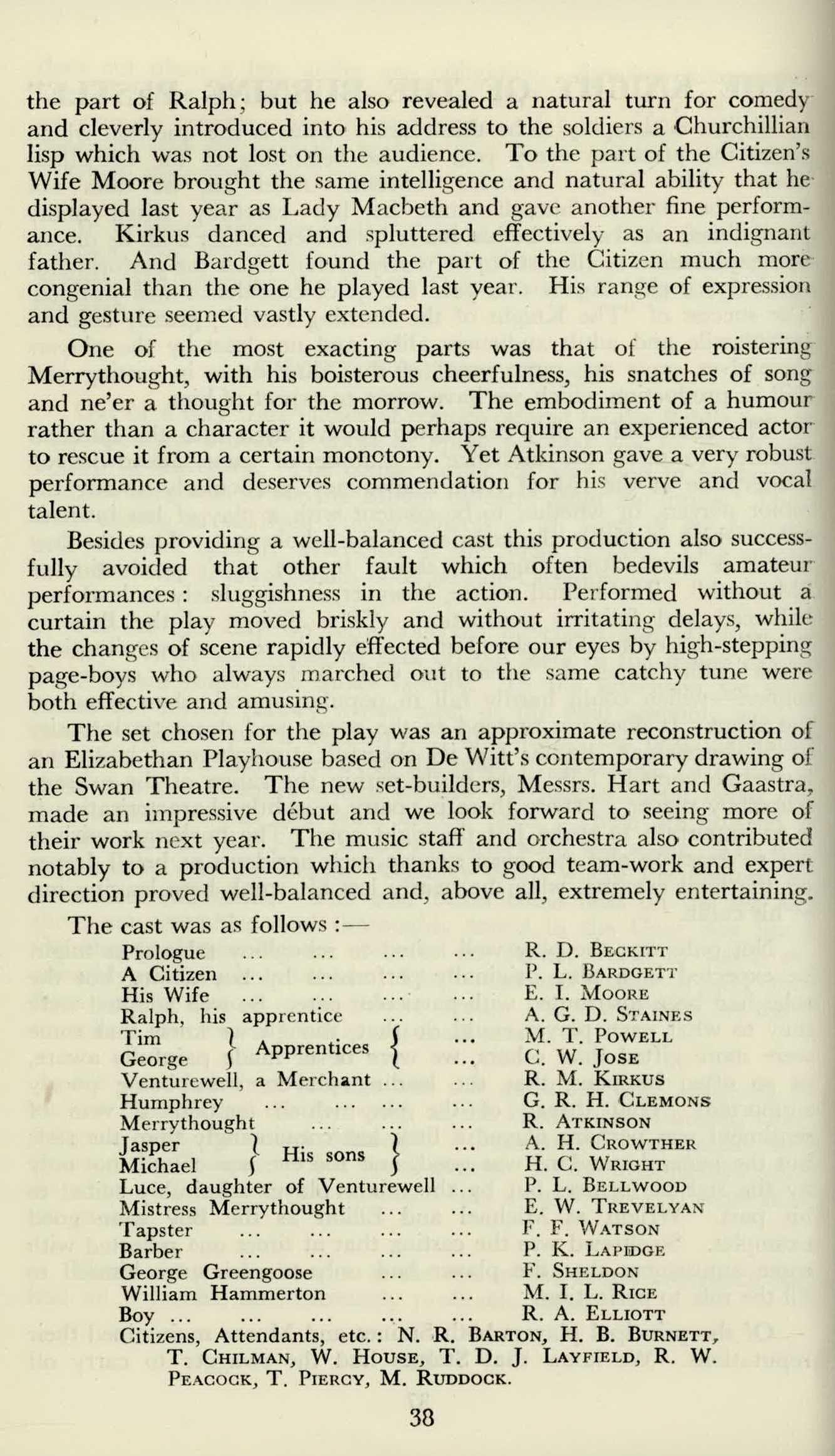

The cast was as follows :- Prologue ... ... R. D. BECKITT A Citizen ... ... P. L. BARDGETT His Wife ... ... E. I. MOORE Ralph, his apprentice... A. G. D. STAINES Tim 1 Apprentices { George j ... M. T. POWELL C. W. JOSE Venturewell, a Merchant ... R. M. KIRKUS Humphrey ... G. R. H. CLEMONS Merrythought ... ... R. ATKINSON Jasper Michael 1 His sons } — ... A. H. CROWTHER H. C. WRIGHT Luce, daughter of Venturewell ... P. L. BELLWOOD Mistress Merrythought E. W. TREVELYAN Tapster F. F. WATSON Barber P. K. LAPEDGE George Greengoose F. SHELDON William Harnmerton ... M. I. L. RICE Boy ... ... ... ... ... R. A. ELLIOTT Citizens, Attendants, etc. : N. R. BARTON, H. B. BURNETT, T. CHILMAN, W. HOUSE, T. D. J. LAYFIELD, R. W. PEACOCK, T. PIERCY, M. RiUDDOCK.

A NOTE ON THE MUSIC OF "THE KNIGHT OF THE BURNING PESTLE"

How many songs that we hear every day on the B.B.C. Light Programme will be easily unearthed in three hundred years' time? The songs of Merrythought in "The Knight of the Burning Pestle" were so obviously well-known in the time of Beaumont and Fletcher that they were never written down in musical notation. But some, though not all, appear now to be lost. Nobody knows the tune and nobody knows where the tune is written down. We found that some researchers had gone through the contemporary music in the British Museum Library and had found little or nothing. Others had sought the assistance of the Old Vic and the British Drama League to no purpose. In some cases the words have gone as well. When Mrs. Merrythought and Venturewell have to sing to gain admittance to Merrythought's house the authors give the first line only of their songs followed by an "etc.". Of those two songs we could not only not find the tunes but neither could we find the words of the remainder of the verse ! "Lost and gone for ever", like Clementine in the song. Could the song Clementine disappear off the face of the earth so effectively that no one in three hundred years' time could trace it? It seems hard to believe.

Some we did find. "Walsingham" is well-known, and "Go from my window, Love, go" (how similar these words are to Gracie Field's "Go away from my window" !), come in the collection of pieces in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, parts of which, though unfortunately not all, are published in popular editions. Others we adapted. "Wolseys wilde", a contemporary tune, was pressed into service and many others. But some of the rhymes, because of odd metres and quaint rhythms, proved obdurate. Then we had to compose our own. And here each tune had to run the double gaunlet of singer and producer. In the end all were satisfied.

The orchestral music presented fewer difficulties. Dowland's "Lachrymae" was easily transcribed and Byrd's "John come kisse me now" proved popular for "furniture music". We could not find "Baloo" but as the orchestra was not supposed actually to be playing it when it was asked for that did not matter. For the rest, the Jig of Hoist's St. Paul's Suite formed the overture, and the Dargason, with the famous and lovely tune of Greensleeves as a counterpoint, the epilogue. For the interval, the Capriol Suite of Peter Warlock, who has been termed "an Elizabethan born out of true time" seemed most

fitting.

F.W.