27 minute read

Kenya’s Potential to Build the First Zero Plastic Waste Capital City in Africa

Birds circling above the waste dumping ground in Dandora and street children mark the site of the waste landfill site, 8 kilometers outside of Nairobi city. Each day thousands of waste pickers, scavenge through the 2000 metric tonnes arriving daily.

Top finds include high-density plastics, bottles, e-waste and metals. Companies such as Mr. Green Africa, see these waste pickers as today’s invisible heroes, and by trading in recyclable plastics, they have not only created recognised employment for many but also recycled more than 3000 tonnes of plastic.

Advertisement

However, there are too few operations like these

because the market for recycled plastics is small and can be easily overwhelmed. As a consequence, the plan for Dandora is to turn waste into energy via a new incineration plant capable of producing 40 MW of electricity.

Liveable cities, such as Nairobi, will increasingly rely on excellent waste management operations, designed around people’s needs and the delivery of a safe and healthy environment. Good waste management is part of making cities more attractive for inward investment and attracting people to relocate.

But anyone living with the smells and hazards coming from landfill sites, open-pit burning and waterways

clogged with litter and plastic waste knows, poor waste disposal can cancel out all the positive impacts of sparkling new buildings and roads.

Nairobi is no different. However, the combination of improvements in county waste management and the 2017 ban on single-use plastic bags, has significantly reduced the presence of plastics in the urban environment. But there are further steps that still need to be taken care of if Nairobi is to be known as a liveable city and center of innovation in sustainability.

Plastics are big business worldwide; by 2022 the market for manufactured plastic products is projected to exceed USD 2 trillion, mainly due to the high demand for textiles. Over the past four decades, global plastics production has more than quadrupled, and of the 9.2 billion tonnes produced, 6.3 billion tonnes have become waste. Of this, 12 percent has been incinerated, less than 10 percent recycled and nearly 80 percent either discarded or landfilled, meaning that 90.5 percent of plastics go unrecycled. This low recycling rate is because of the complexity of resin mixtures and the lack of information about the disposal of different plastics.

On the other hand, the negative impacts of plastics on the environment and society are also significant. The toxic chemicals which leach out of plastics are harmful to thousands of informal waste pickers. They also cause significant losses to maritime industries, damage infrastructure, and flood defenses, and contaminate water and the air we breathe. Liveable cities, such as Nairobi, will increasingly rely on excellent waste management operations, designed around people’s needs and the delivery of a safe and healthy environment.

Based on current trends, plastic production will contribute up to 17 percent of the global carbon budget and already contribute to losses of USD 500 to 2500 billion from the world’s marine ecosystems. And the growing quantities of discarded plastic waste are the outcome of multiple market failures, that reflect plummeting oil prices, leading to a dramatic decrease in the value of plastics and the price of virgin feedstocks, a throw-away culture, and people’s negative attitudes towards using recycled materials.

Companies are being forced to make tough decisions about whether recycling is still an economically viable option or not. Many consumer brands, including beverage companies, some

of the largest sources of plastic pollution, could have difficulties meeting previous commitments to adopt more sustainable practices by replacing portions of their products with recycled plastic.

On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a stress test for the 4Rs – refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle – the principles for strategies to prevent plastics pollution, raising fears that reused or recycled plastic products may not be hygienic. Unfortunately, plastics have become indispensable during the pandemic, and in many places efforts to reduce the use of plastics are being rolled back as frontline workers have demanded greater supplies of personal protective equipment.

Conversely, there are African entrepreneurs and scientists who have been able to respond in more innovative ways more reflective of a circular economy. Peter Okwolo, for example, a co-founder of Takataka Plastics in Gulu, Uganda, took just one week to design, test, manufacture affordable COVID face shields using recycled plastic waste, and which are now being used in medical centers across the country. There are also emerging machine learning technologies coming on stream to help sort waste from different feedstocks for recycling and deliver high-quality inputs from mixed plastic waste.

Consumers often choose plastic products with harmful colorants and plasticizers, which are more expensive to recycle and more hazardous as waste. Removing these additives or replacing them with simpler and more homogenous molecules can make recycling easier. But potentially,

the best solution is to replace fossil-fuel-based plastics, with bio-based plastics. Not only can biobased plastics emulate many of the features of plastic, such as their light weight, transparency, and flexibility, without harmful chemical additives, they can also deliver hygiene, biodegradability, and a new sustainable fashion and design culture.

Professor Irene Samy at the Nile University in Egypt has developed a unique alternative to plastic by turning dried shrimp cells into thin films of biodegradable plastic for eco-friendly grocery bags and packaging. By utilising chitosan – a material found in the shells of many crustaceans – her team has been able to produce a clear, thin plastic that is completely degradable in the environment.

Considering the large quantities of shrimp shell waste produced each year in Kenya, Strathmore Business School is now looking at chitosan-based plastic to drastically reduce plastic waste and create new markets for biobased plastics. Replacing synthetic polymers with a natural form of polylactic acid would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 800 million tonnes every year. Using biobased plastics in textiles would also dramatically reduce the concentration of microplastics in drinking water supplies, and coastal fisheries.

Thinking ahead to a post-COVID time, Nairobi could potentially focus on becoming a capital city with zero-plastic waste. Not only would urban life be enriched by a cleaner environment, but the use of biobased plastic materials produced locally would open up opportunities across the Kenyan economy for bio-waste to be processed into specific feedstocks for different plastic uses, especially in packaging.

To achieve such an outcome would require several steps to be taken. For example, building awareness about the benefits of a city with zero-plastic waste, and how to achieve it using realistic, alternative sources of materials. Creating the demand for biobased and recycled products by addressing pervasive psychological and behavioural barriers, such as the need for highly coloured packaging or the perception that reused or recycled products are unhygienic.

Investing in localised production facilities to deliver biobased feedstocks and materials for manufacturing. Developing new business models for the collection and sorting of plastic waste, using local professionals to build trust in the safety of sorted waste and prepare clean, homogenous plastic streams for recyclers. Establishing new policy incentives that encourage circularity. For example, bans and fees have been able to shift some behaviours, but Kenyans could scale up sustainable plastic solutions through clear bioplastic and recycling labels and standards, and the use of taxes or fees on plastic products that use virgin fossil-fuel feedstocks, are expensive to recycle, or which cause environmental and health hazards.

Every piece of plastic discarded in our cities, whether it is a food packaging, cigarette ends, milk cartons, synthetic fabrics, baby wipes, and diapers, or personal care products, will eventually end up clogging our waterways and breaking up into microplastics, potentially harming our health and wellbeing. A zero-plastic waste future is one that will turn our cities into liveable spaces for everyone.

Article by Prof. Jacqueline McGlade, Faculty – Strathmore Institute for Public Policy and Governance (SIPPG). She is also the lead author for the UN Environment Global Assessment on Marine Litter and Plastics to be released early 2021.

Leadership in Crisis: Leaders and The Grief Cycle

Grief is a word that encompasses many emotions: sadness, unhappiness, resistance to change, anger, fear, and regret.

In today’s world, there are many things that can cause grief. With the COVID 19 pandemic sweeping across the world, people all around the world are struggling to find ways of coping and managing their personal lives. Many have lost jobs or their sources of income. Businesses have folded or are on the brink of doing so. Others are unwell, with pre-existing medical conditions. And yet others have been infected with the coronavirus and are struggling, fighting for their lives.

This is one time the world is united in scenes of

grief. Stories from countries like Italy, the UK, and the US on the loss of lives mean people are going through a lot of grief.

In 1969, Elisabeth Ross wrote a book called On Death and Dying. In it, she outlined the 5 stages of grief and loss, more popularly known as the Kubler- Ross Model. These stages are denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. One of the first things she highlighted was that these stages do not necessarily occur in order. She also pointed out that not everyone goes through all the stages. But it is a useful model to use to understand how to help those who are going through grief and loss and can be applied to any situation.

Take for example an individual who owns and runs an events company. The events industry has been hard hit by the COVID 19 pandemic. Restrictions on gatherings mean that it isn’t possible to hold events, conferences, or engage with customers via roadshows. This is likely to be the case for the foreseeable future, as the coronavirus continues to ravage populations across continents. This entrepreneur is anxiously waiting for the lifting of restrictions with the hope that ‘corona will end’ and life can go ‘back to normal.’ A good example of someone in denial and who has refused to see the reality for what it is. Denial is a defense mechanism as it helps us deal with the pain from the problem.

The next stage is anger. The country is going through severe hardships. People are struggling to make ends meet. Many are going hungry as the counties continue to be locked down and travel remains tightly controlled. Never in the history of Kenya has there been a dusk to dawn curfew that has lasted this long, and yet the event organizer is angry.

Angry at the Chinese because he believes they eat bats that harbored the virus. Angry at the restrictions forcing him to stay home unable to engage clients and get new business. Angry at the authorities for forcing him to wear a mask as soon as he steps foot outside his house. Angry at not knowing what is coming next. Anger is an emotion that if left unresolved can consume you and eat away at your soul.

The third stage is bargaining. This stage has a lot of reflection most of which use the ‘if only’ approach. If only he had closed the deal on more conferences. If only he had taken down payments, he wouldn’t have suffered losses from the events he had to cancel. If only he went to church more

often, then God wouldn’t have let this happen to him. This stage is also compounded by guilt and a lot of questions. It can result in self-doubts where one wonders what else he could have done to foresee the situation.

The fourth stage is depression. In the case of our event’s organizer, he is now looking at his life which he may perceive to be in shambles. He doesn’t see any way out. He is deeply sad, perhaps even unable to think of a way out. The emotions are weighing heavily on him and he may not be able to do much.

The last stage is the acceptance stage. Here there is a level of calmness that arises from accepting the situation. It is not a happy stage by any standards, but it isn’t depression either. This is a stage of exploring options and of finding a way forward. Our events organizer finally accepts that everything happening is beyond his control and sits down to review what he does have control over and what he can

As a Head of Sales and Marketing, you are most likely to have a team that is looking up to you to provide direction under this crisis situation. Targets are still in place, sales must come in, yet these front-line customer-facing employees are unable to do their work in the traditional way that is known to them. It calls for you as the team lead to use all your leadership skills to keep the team together and motivated so that you find ways to go about your tasks no matter how challenging the circumstances. As a leader, you need to have those 1 on 1 conversations with individuals to encourage and coach members to get to the acceptance stage so that the way forward can be found. As a group, the members may need to help one another by providing support and help.

How can you tell if you or your colleagues are going through grief? There could be several symptoms that may point to that. These include feelings of worry or anxiety, depression, loss of sleep, headaches, frustration, guilt, and general stress. In severe cases, a qualified counsellor or doctor would be best placed to help diagnose mental health challenges. In not so severe cases, or where people get to the acceptance stage quickly, it could be possible to work with People handle stress and grief very differently and based on their personalities and life experiences. There is rarely a model or template that one can use to manage these situations. One thing is clear, the COVID 19 pandemic is going to be with us for some time. What are you doing as a leader to help yourself and your colleagues through this?

As C S Lewis said, “Grief is like a long valley, a winding valley, where any bend may reveal a totally new landscape.”

Article by Thrity Engineer- Mbuthia. She is the current Acting Chair – Chartered Institute of Marketing Kenya.

She is also a leadership coach with an interest in Personal Development at Strathmore University Business School.

This article was first published in the Marketing Africa Magazine

Sustainability: The New Business Mind-Set for The Financial Sector

In today’s business community, sustainability is becoming the new frame that every organization is using to assess its own outcomes. It is also being used as an expression of the issues that production and consumption patterns will have to address to build a sustainable city where individuals and the environment are respected. This means that business communities and suppliers cannot continue to operate through ‘business-as-usual’.

This came out clearly during a supplier’s conference hosted by Absa Bank-Kenya to introduce their suppliers to a new Enterprise Resource Management (ERP) system. Attended by over

400 suppliers, this provided a unique opportunity to achieve Sustainable Development goals ‘Making Everyone Count.’

They were able to discuss how their work within the organization’s supply chain is always linked to sustainability in line with environmental, risk, and waste costs. And how they can integrate environmentally sound choices into supply-chain management.

Unlike before when banks had been synonymous with the number of clients, they were making profits, this is not the case anymore. Banks like Absa have now incorporated social and environmental stewardship and ethics into organizational practices.

This, therefore, calls for organisations and even suppliers to have a clear understanding of sustainability and to adopt sustainability initiatives for their day to day work such as energy savings, management of waste products, reduction of pollution, understanding their role in climate change, and encouraging innovation.

Operating under this new paradigm shift of organizational sustainability requires new ways of doing business; responsible production and consumption; and new leadership thinking to understand and seize the challenges and opportunities of sustainable development.

In response to this context, BBK-ABSA and Strathmore University Business School (SBS) have jointly developed a ‘Suppliers Sustainability Leadership Blended Training Program’ meant for the Absa suppliers. The programme aims

at building the capacity of suppliers to integrate the SDGs and the Paris Climate Agreement into their business strategy and turn sustainability initiatives in their organization’s drivers of measurable Value. Using the approach of sustainable and inclusivity this initiative provides a chance of decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation, while at the same time creating employment and fostering clean energy innovation.

It is also responding to the Principles for Responsible Banking, a global framework that guides the integration of sustainability across all business areas of a bank starting from strategy to portfolio and to transaction level and

aligning the banks’ business with the society’s goals. From the bank’s strategy to all transactional levels and across all business areas it is helping the banks contribute to creating value for both society and shareholders, and help them build trust with investors, customers, employees, and society.

Sustainability, therefore, is not just another social responsibility program. It has become a fundamental way of doing business and where cities can efficiently tackle climate change through networks by sharing knowledge and building capacity.

Article by Rosemary Okello-Orlale, Director of Africa Media Hub- Strathmore University Business School

The Role of Organisational Support in Helping Employees cope with the Effects of COVID -19

INTRODUCTION

This article focuses on how organisations can support their employees during and after the pandemic. We focus on perceived organisational support, employee perceptions on how well the support is being delivered, understanding the emerging complex needs of employees and some of how organisations can support their employees.

PERCEPTION MATTERS

Perceived Organisational Support refers to employees’ beliefs concerning the extent to which their organization cares about their well-being and values their contributions. POS has been found to have important consequences for employee per-

Employee perceptions of a lack of support from their organisation can result in increased absenteeism, disengagement, conflict, turnover, fatigue, stress, burnout and anxiety among other issues. Lack of psychological support can result in loss of productivity, increased costs and greater risk of accidents, incidents, and injuries (A Workplace Guide to Psychological Health and Safety, n.d).

ORGANISATIONS WITH A MIND AND HEART THAT UNDERSTANDS

In 2019, less than 10% of business leaders from G20 and OECD countries considered a pandemic as a looming global risk, nor did they anticipate that a pandemic might test their public reputation as a responsible employer. While presently there is a major focus on the public health and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the workforce and societal implications are no less profound (WEF 2020).

During a complex emergency like the COVID–19 pandemic, leaders find themselves in a position where they are expected to ensure that business operations continue, while at the same time ensure that support staff delivers. It is therefore commonplace to find that most of the support provided to staff is geared toward ensuring they are able to continue working comfortably. Whilst this is necessary, leaders must not lose sight of the psychosocial needs of their staff. Understanding these needs will help in reducing the negative effects of the pandemic and sustain their functioning so that they can participate in the recovery process post the pandemic. Research has shown that where employees feel they are supported by the organization, the greater their job attachment, job commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement, desire to remain with the organization, organizational citizenship behaviours (discretionary behaviours that are beneficial to the organization and are a matter of personal choice), and job performance (A Workplace Guide to Psychological Health and Safety, n.d). Organizational support is a critical factor in ensuring organisational Resilience.

Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007) define resilience as ‘the maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions such that the organisation emerges from those conditions strengthened and more resourceful.’ Extreme or ongoing stress often impairs people’s ability to concentrate and to make good decisions. You may find that your staff members and yourself are unable to function at your usual level, right at a time when extraordinary performance is needed. Addressing personnel’s psychosocial needs to the extent possible is not merely kindness, but an essential step that will help them recover their professional capacity. (Psychological Support, n.d. & leadership In Emergencies Toolkit, n.d.).

ORGANISATIONS – CREATING SUPPORTING HANDS EMPLOYEES CAN RELY ON

The following are some of the ways in which organisations can support their employees:

1. PSYCHOEDUCATION

Employees are likely to experience a variety of negative reactions during and post the pandemic. Psychoeducation helps to create awareness about typical reactions so that people understand they are not overreacting, being weak, or going crazy. Organisations can organise awareness sessions for the employees by a staff counselor or available resources within their location. In some organisations, ice-breaker sessions have been organised every 2 weeks where employees, from top to lower management, talk about social issues other than normal work challenges. This creates a stronger bonding capital for the organisation and social capital necessary for the firm to survive postCOVID-19.

2. TRAINING

Provide education and training to all staff to heighten professional and mental health awareness (i.e., mental health literacy). The critical question is how this training can be done and where it can be accessed? Some institutions are currently offering free sample online courses and it is the duty of the line manager to ensure employees engage in relevant staff development courses (i.e. according to professional and mental health needs). In addition, the organisation can provide information on mental health issues to all staff whose role involves leading, supporting or managing. Some organisations have provided links to social media sites and media channels that offer

aerobics and physical exercises within limited (home) spaces.

3. SOCIAL SUPPORT (FORMAL AND INFORMAL)

During a particularly prolonged or intense crisis response, leaders can consider creating a ’buddy system ‘within departments to help with monitoring each other for warning signs of mental health issues. It is important to provide a sense of safety and a supportive recovery environment for your staff as quickly as possible, recognising that they may need time to take care of their family needs. If possible, organize online ceremonies where personnel can come together, first to acknowledge and mourn shared losses, and then mark positive developments as the recovery continues. Even if progress is slow after a large-scale event, celebrating small milestones can help keep staff members focused on recovery rather than dwelling on what was lost.

4. COMMUNICATION

Organisations need to support their employees through clear communication during all phases of an organization’s response to COVID-19. Respectful workplace communication should be encouraged especially such that psychological health concerns can be discussed safely and openly. Efforts should be made to ensure awareness is created of company benefits and programs that employees can access to address their psychological health concerns. Where employees who are off work due to mental health concerns, team leaders should make an effort to maintain regular and supportive communication with them. Regularly check-in and keep all staff informed about the emergency situation and work arrangements

5. FORMAL POLICIES & PROGRAMS

At the organisational policy level, leaders need to consider providing comprehensive benefits that support employee mental health (i.e., coverage for the following: psychologists or other regulated mental health professionals; Employee and Family Assistance Programs; prescription drugs). Develop programs and procedures to address occupation-specific risks to psychological health and safety. It would be useful for organizations to identify a contact person who is knowledgeable about mental health issues and is responsible for facilitating healthy and successful work-returns. Organisations should formulate detailed return-to-work plans that

include a range of options for coping with mental health concerns (e.g., graduated return-to-work). It is important to ensure coordination among key participants in the return to work process.

6. CLEAR LEADERSHIP & EXPECTATIONS

A work environment where there is effective leadership and support that helps employees know what they need to do, how their work contributes to the organization, and whether there are impending changes, increases employee resiliency and well-being. It also important the leaders protect their staff from organizational and political stressors while recognizing organizational limitations. Effective leaders are transparent, empathetic and create trust, and their behaviors help calm, support and even energize employees so that they feel vested in a common mission and purpose, and embrace new ways of working (WEF 2020).

7. SELF-CARE

Educate staff members about the need to practice selfcare. In as much as it is possible leaders should model good coping mechanisms for staff during normal work periods and throughout crisis response.

There are also a few things organizations should avoid: • Do not force or pressure people to share their stories with you. • Do not allow people to self-disclose at their own pace and in their own way. • Do not tell them how you think they should feel or what they should have done differently. • Do not explain to why you think they experienced this

disaster based on your opinions or beliefs. • Do not make promises that you cannot keep. For example, do not confidently reassure survivors that assistance or resources will soon arrive or that you will be available to help them over a long period of time if you do not know for sure. (Psychological Support, n.d., leadership In Emergencies Toolkit, n.d., & WEF 2020).

CONCLUSION

It is important that leaders are aware of these stressors as they are also likely to face them as they support their teams and they too need to maintain their own personal and professional resilience. Leaders need to pay attention to how the pandemic may have impacted them at a personal level so that they also maintain their own resilience.

Experiencing a complex emergency like the COVID-19 pandemic does not always result in negative outcomes. Research has shown in some cases there could be positive outcomes such as feelings of empowerment during times of crisis and chaos, emotional connection with survivors, colleagues, and the community; a sense of competence and mastery in overcoming unique challenges; a sense of privilege and honour to serve during times of need; increased self-knowledge and self-awareness; personal growth and being part of a meaningful effort larger than oneself. Organisations can use this time to grow employees at an individual level and by implication the whole firm (Psychological Support, n.d., leadership In Emergencies Toolkit, n.d., & WEF 2020).

REFERENCES

A Workplace Guide to Psychological Health and Safety (n.d.). Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.guardingmindsatwork.ca/about/about-psychosocial-factors Eisenberger et al., 1986, Perceived organizational support Journal of Applied Psychology, 71 (1986), pp. 500-507

LEADERSHIP in EMERGENCIES TOOLKIT (n.d.). Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.un.org/epst/ sites/www.un.org.epst/files/leadership_in_the_emergencies_toolkit.pdf

Mees B, McMurray A & Chhetri P 2016, Organisational resilience and emergency management, Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 38–43. At: https://ajem.infoservices. com.au/items/AJEM-31-0208

Psychological Support- Workplace Strategies (n.d.). Retrieved April 8, 2020, from https://www.workplacestrategiesformentalhealth.com/content/images/agenda/ pdf/1_Psychological_Support_EN.pdf

Vogus TJ & Sutcliffe KM 2007, Organizational resilience: Towards a theory and research agenda. IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 2007, New York, IEEE, pp. 3418-22.

World Economic Forum (2019): Workforce Principles for the COVID-19 Pandemic Stakeholder Capitalism in a Time of Crisis: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/ WEF_NES_COVID_19_Pandemic_Workforce_Principles_2020.pdf

Article by Dr. Angela Ndunge, Deputy Executive Dean, Strathmore University Business School.

The Strathmore Hult Prize Chapter

As the world advances, there are certain issues that still remain prevalent, even as more keep popping up. The youth are the future of the world, however, in terms of leadership, it is still spoken of as a theoretical truth. This need for growing problems and an aging ‘golden population’ that was once the youth of today is what prompts the need for the existence of the Hult Prize. The Hult Prize commenced in 2010 with its main agenda forwarded by Ahmad Ashkar founder and CEO of Hult Prize, which was to leverage the crowd and aid young people in generating startup ideas that can sustainably solve the world’s most critical problems. Ten years down the line, it has seen an investment of more than 50 million dollars worth of capital and ideas that have caused

The Hult Prize competition is a global student-centered movement that revolves around business ideas that are aimed at solving various social problems across the world. It brings together some of the brightest and most innovative students from all over the globe in a means to create an environment that can foster innovation of business ideas that are geared towards solving social problems.

The on-campus competitions are the grassroots competitions that act as a source point for entrepreneurs and ideas. However, the purpose of the on-campus competition goes beyond

sourcing ideas that can advance to the regional levels. It provides grounds in which the best and brightest get to engage on an intellectual level on matters of social enterprise. Participants compete for an opportunity to advance to the Regional level which takes place in 25 cities around the world including Strathmore University from which winners then get to advance to the accelerator program hosted in the United Kingdom. The accelerator program gives participants the opportunity to better their ideas through providing an environment where they can make improvements on their prototypes as well as getting advice from industry experts in preparation for the world finals that are held in September every year at the United Nations headquarters in New York and the winner is awarded 1 Million dollars.

Last year’s Strathmore On-Campus edition was held on the 8th and 9th December 2019 and saw over thirty teams pitch their ideas. The panel that made the final decision comprised of individuals from different industries and this

ensured that whichever business idea was presented, there was someone to adequately evaluate it. This proves that there is a hunger for social and economic change in the African continent. Ideas from fashion to education, energy to marketing among others were brought forth and panelists from the relevant fields were present not only to critique but also to provide tips and further insights. A lot was put in to ensure no stone was left unturned to produce the best teams to represent Strathmore in the Regionals. Furthermore, the broad panel acted as a spotting ground to promote and mentor ideas that seemed promising but wouldn’t make it to the next level. At the close of the on-campus competition, Strathmore University

was named as the 2nd best university in the on-campus programmes for the period 2019-2020 worldwide. This achievement brought about it being named as one of the regional centers for Hult Prize 2021.

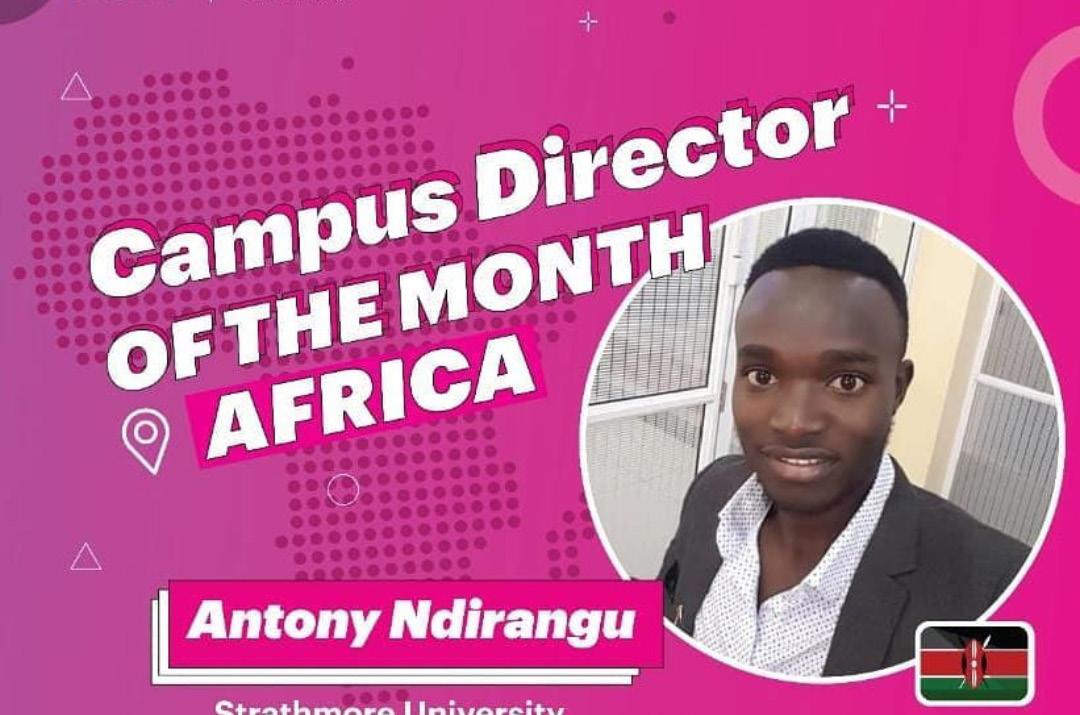

This year, the Hult Prize is back and currently ongoing. This year’s challenge is FOOD FOR GOOD whereby students are tasked to come up with business ideas that will use food as a vehicle of change to reimagine food supply chains and create over 10 million jobs by 2030. The On-campus event will be held on the 27th and 28th of November 2020 and we are looking forward to seeing the new ideas that students have around food and as Muhammad Yunus said “young people should think in a different way, they should be job givers and not job seekers”

By Anthony Ndirangu Campus Director Strathmore Hult Prize Email: anthony.kifue@strathmore.edu

BUSINESS SCHOOL