10 minute read

DC has 420 housing vouchers for youth leaving foster care. Why isn’t it using them all?

from 04.05.2023

When Ronnie Harris first entered foster care at 12 years old, she was certain she would be adopted. But, in what felt like no time at all, foster care swallowed her teenage years. The system jerked Harris across the city. Each time she moved, she hoped the next house would hold adoptive parents and her own room. But it never did.

After leaving a particularly neglectful placement, Harris became homeless at 20. She was still experiencing homelessness when she turned 21, the milestone that marks the date young people age out of the foster care system in D.C. At the time, the District had dozens of housing vouchers available for young people in foster care who turn 21 without the resources to rent their own apartment. Yet, in the nine years she had spent in care, agency staff never told Harris, now 22, that such vouchers existed.

Advertisement

“All our life we’ve been having to depend on people and depend on the system and even though the system is supposed to be there for us, half the time it wasn’t,” Harris said when she first learned about the vouchers. “Overall, I just feel like the system really set me up for failure.”

Each year, 40 to 100 people “age out” of foster care in D.C. The city’s child welfare agency says people like Harris, people who age out of the system into homelessness, are rare. But advocates for people in foster care say it’s more common for youth to become homeless shortly after leaving the system — in 2022, 12% of people counted in an annual survey of people experiencing homelessness in D.C. had been involved with the child welfare system.

Housing instability among former foster youth is a problem across the United States. National studies estimate between 25% and 50% of people who leave foster care experience homelessness within four years. Due to a lack of support during their time in care, many system-involved young people don’t have a job, savings or anyone they can turn to. Harris aged out with just food stamps to support her.

The federal government funds two voucher programs that provide up to five years of housing for former foster care youth first striking out on their own — the Family Unification Program (FUP) and the Fostering Youth to Independence Initiative (FYI). But D.C. has failed to use all the vouchers available for the city over the past several years, even as people leave foster care for unstable housing conditions or, in Harris’ case, homelessness.

D.C.’s 82 available vouchers

The mission of D.C.’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) can be summarized in one word — permanency. After the 30-year LaShawn v. Bowser lawsuit found D.C. was failing to provide basic care for children, CFSA implemented a series of improvement plans, which changed every aspect of the agency, from its position in D.C. government to its new focus on prevention. CFSA now aims to remove fewer children from their homes, to reunite them with their biological parents when possible, or to place them with permanent adoptive families, Director Robert Matthews has shared at oversight hearings. The goal, CFSA officials say, is to give children stable support networks. Harris said the policy has another consequence: Young people who are never adopted feel left behind.

CFSA offers programming for older youth through the agency’s Office of Youth Empowerment. As people in foster care get older, they can participate in match savings programs, financial literacy training and a weekly program called LifeSet that helps young people find housing, education and employment.

By 19, young people begin meeting with CFSA staff regularly to make a housing plan for when they age out of the system. But in Harris’ case, the interim plan for the time before she turned 21 felt equally unstable. Harris wanted to leave her foster home. Her foster parents weren’t using the money CFSA paid them to take care of Harris, she said in an interview. Fed up with holey shoes and never having enough to eat, she asked CFSA to find somewhere else for her to live. When staff only offered options she knew wouldn’t work for her, Harris decided to leave.

“I kept telling them I didn’t want to be placed in XYZ home — OK, you could have found something else for me,” she said. “I shouldn’t have been, like, homeless basically. Even though I made the decision, I’m still a ward of the state.”

Young people who age out of foster care generally don’t have the same support many others take for granted, and they are often affected by systemic inequities. While the District’s youth population is 54% Black, 80% of D.C. children in foster care are Black. Child welfare advocates have long pointed out that nationally, child welfare agencies remove Black children from their families at disproportionate rates, often citing reasons related to poverty.

The disparities young Black people already face are exacerbated by experiences with foster care. People who spend time in care are less likely to have graduated high school, less likely to be pursuing higher education, less likely to be employed, and less likely to have money saved than young people who aren’t in care. And many don’t have strong relationships with mentors able to offer advice or a safe place to land. So making a housing plan, with the help of CFSA, is crucial, according to Sharra Greer, policy director at the Children’s Law Center.

“If you’ve got no job history, [if] you haven’t graduated high school, that’s a steep run,” she said. “If they are going to be aging out without that legal permanency, what are we doing to make sure they are successful?”

In D.C., a housing voucher has rarely been part of that plan.

Since 2018, D.C. has had a total allocation of 421 FUP vouchers from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The vouchers are available to people aging out of foster care as well as to parents for whom housing is a barrier to keeping or reunifying with their children. FUP vouchers provide up to five years of housing assistance and supportive services for young people, who are eligible if they have an extremely low income, are unstably housed and do not have readily available resources or support networks.

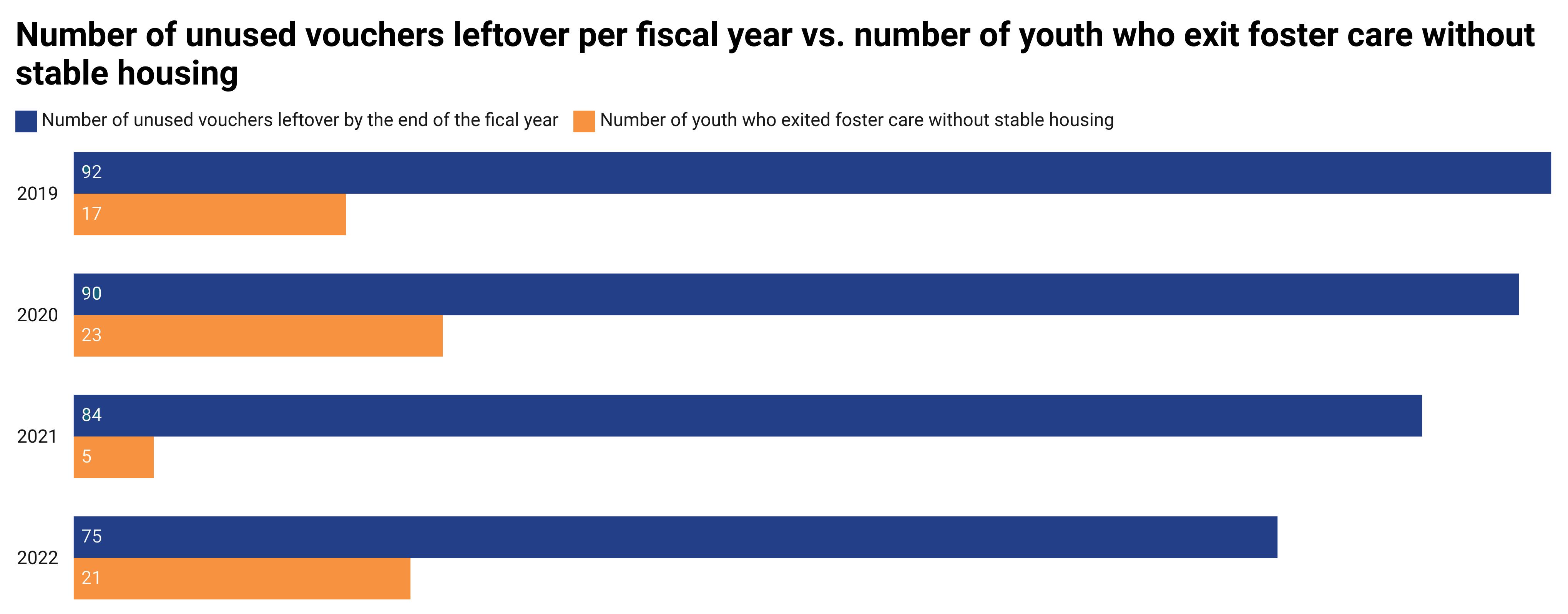

For the last four years, CFSA has had at least 75 unused vouchers available, according to data provided by HUD. As of January, D.C. had 82 vouchers available — nearly 20% of the total allocation. While a HUD spokesperson wrote in an email that the District’s FUP voucher utilization rate is close to the national average, advocates who work with youth find the failure to use all available vouchers concerning, especially as young people enter unstable housing.

“It’s like cognitive dissonance — what’s going on?” said Ruth White, co-founder and executive director of the National Center for Housing and Child Welfare.

In fiscal year 2021, oversight documents submitted to the D.C. Council show CFSA gave seven FUP vouchers to families and do not include a number for youth, though advocates report young people were actively applying for vouchers. Oversight responses from fiscal years 2022 and 2023 show several discrepancies. For instance, data shows a total of 28 young people received a FUP voucher. However, over the same time period, data shows only four people planned to live on their own once aging out. (CFSA oversight documents for 2015 to 2020 either do not mention FUP vouchers or do not say how many vouchers CFSA distributed to young people.)

CFSA did not respond to multiple requests for comment about homelessness among foster youth, the process of finding housing for young people aging out of foster care, or D.C.’s use of FUP vouchers. Specific requests included information on how many FUP vouchers the agency provided to young people in the last eight years, as well as clarification of discrepancies between available CFSA and HUD data.

Harris isn’t the only potentially eligible person who never heard about the vouchers. Typically, youth and their advocates say, CFSA staff come to transition meetings with a housing plan already in mind. Many young people are never told about vouchers, several people interviewed said, unless they bring up the possibility themselves. Those who ask about vouchers can be met with skepticism, said Ashley Strange, a former program manager at CASA DC, an organization that supports young people in foster care.

CFSA denies the majority of applications for vouchers, Greer said, without either the applicants or their advocates fully understanding why. CFSA’s criteria for allocating vouchers beyond the eligibility rules established by HUD is not public, and advocates for young people in foster care said the agency declines to share it with them. Greer and Strange say they’ve heard CFSA staff deny vouchers because the applicants aren’t ready.

“But ready for what? What’s your criteria for readiness? They’re going to age out into homelessness,” Greer said. “It just seems like when you have so many youth who are aging out into homelessness that you would want to be generous in your distribution of these vouchers.”

Aging out into housing instability

After Harris left the foster care system, she moved around until finding a spot in a local transitional housing program. She remained in contact with CFSA while she was homeless, but was never offered any resources specifically for people who have been in the system, just the contact information for local housing programs, she said. When Harris reached out, only one of the organizations responded. She applied on her own for food stamps, the only income she has now.

The transition from having a life governed by the system to almost no support was jarring.

“All our life we’ve been having to depend on people, depend on the system even though half the time the system wasn’t really there for us,” she said. “You have somebody that you can depend on — I don’t have that. I had that, but I don’t anymore.” Instead of moving into an apartment of their own, people leaving foster care often end up at transitional housing programs or moving in with the same biological family members who did not take them in while they spent years in the system. In fiscal year 2022, 38 young people aged out of care in D.C. Just 15 were employed, and the most common housing options were a placement with biological family, foster family or transitional housing, according to CFSA oversight responses. D.C. doesn’t track people after they leave care, so CFSA doesn’t know how many of those initial placements are successful.

In public hearings, CFSA officials say that the availability of other options make vouchers less necessary, and contend that youth fare better when they live with family. “You don’t give a youth a voucher when you know they’re going to have to pay market rent when they emancipate and can’t sustain it,” CFSA Director Matthews testified this February.

When asked about homelessness among people formerly in foster care in a hearing last year, agency officials said it wasn’t a problem; since 2015 just six people have left foster care directly for shelters, according to CFSA oversight responses. But another 18 were characterized as being in abscondence on their 21st birthday, meaning the agency didn’t know where they were.

And just looking at the initial numbers doesn’t provide a full picture, according to Amy Dworsky, a senior research fellow at the University of Chicago who has written extensively about housing and foster care. Homelessness often comes six months or a year later, Dworksy said, when whatever housing option young people chose falls through, frequently because family support peters out or savings dry up. Local young people say the CFSA-provided options often don’t work, as will be explored in an upcoming article.

On the path to change?

With young people reporting a clear need, why hasn’t CFSA used all the vouchers?

CFSA officials, when asked in oversight hearings, generally say it’s because young people have other options. HUD, which is hoping to increase voucher utilization across the nation, said the D.C. Housing Authority cites low referrals and few available units, a spokesperson wrote in an email. While CFSA connects youth with vouchers, the housing authority is the agency that actually administers them on behalf of HUD.

Many jurisdictions reserve some of their FUP vouchers for families, said Mike Pergamit, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute who has written about the program. While it’s unclear if D.C. does this, Melody Webb, CEO and co-founder of Mother’s Outreach Network, said parents in need aren’t getting the vouchers, either. One mother, who asked to be included anonymously, said she’d never heard of the voucher despite receiving multiple threats that her kids would be removed, due in part to her homelessness.

And beginning in 2019, D.C. had no need to worry about running out of vouchers, White said. As head of the National Center for Housing and Child Welfare, she worked with a group of former foster youth to create the federal government’s FYI voucher program, through which HUD provides on-demand vouchers for youth aging out of foster care. If D.C. ever uses all its FUP vouchers, the program can provide CFSA with up to 50 vouchers each year, enough to cover most foster youth in recent years.

“They could have solved homelessness for every foster youth,” White said of D.C. officials. “And they chose not to do that.”

That may be changing.

Late last year, the D.C. Council passed a bill that includes a provision requiring CFSA to screen all young people aging out for a FUP voucher. Ward 1 Councilmember Brianne Nadeau, who introduced the legislation, was hopeful the law would push CFSA to encourage more youth to apply for the vouchers.

“What we don’t want is people exiting the foster system and going straight to the homeless services system. … That is not acceptable — that shows that we haven’t done the work to help create stability for youth exiting,” she said in an interview last fall.

CFSA, which opposed the bill initially, is now required to include in every housing plan either an intent to apply for a voucher, or an explanation of why the person is not eligible for one. The agency is also preparing to apply for FYI vouchers once the utilization rate reaches 90%, a stipulation in the federal law establishing the newer program, according to this year’s oversight responses.

Meanwhile, Harris lives in a transitional housing program. She’s making plans — she’s in a nursing program, and looking for a job. She’s doing what she can to make things work. But when she thinks about her time in foster care, she still feels incredibly let down.

“When we age out of the system, it’s like we no longer exist to them,” she said. “I feel like I shouldn’t have been able to age out of the foster care system [without more help]. … Something should have happened.“

This article was co-published with The DC Line.