7 minute read

Street Papers adapt to a new reality: Coronavirus and a world in lockdown

by Tony Inglis / Courtey of INSP.ngo

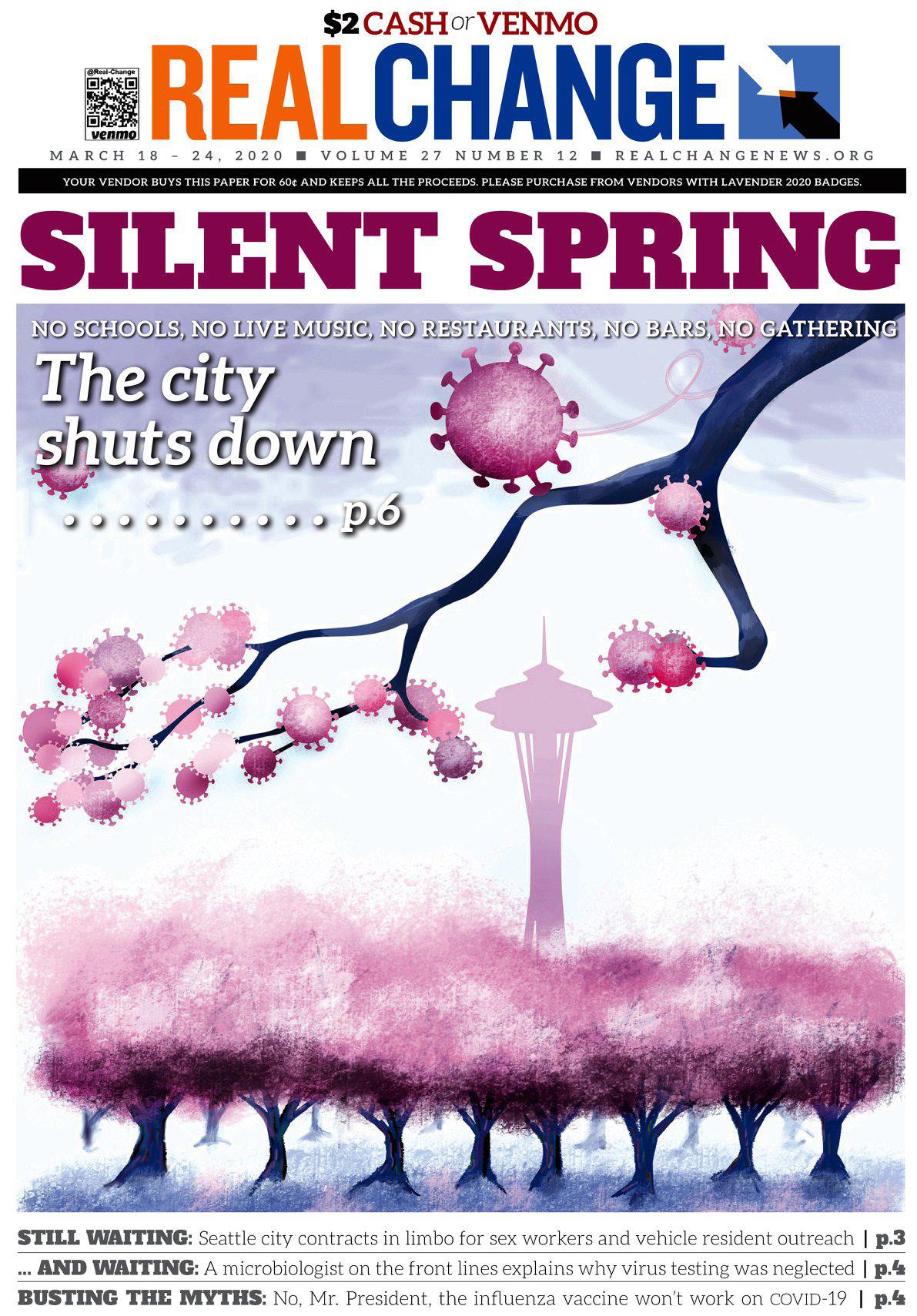

The coronavirus outbreak has put organizations of all stripes and missions in unfamiliar territory, and this is no less true for street papers. The majority have been forced to take the unprecedented steps of temporarily pausing printing and telling vendors not to sell their publications on the streets, completely upending their usual operations to fall in line with health guidance advising people work in isolation and practice social distancing in an attempt to halt the spread of the virus.

This leaves street papers with a new set of challenges. One of the major tenets of the street paper mission is allowing vendors to come face-to-face with members of the public, carrying out a transaction whereby they buy the street paper and sell it for a profit. Not only does this provide a livelihood, but it makes a community of people, often marginalized and vulnerable, totally visible. COVID-19 has created an environment that makes this nearly impossible in just about every one of the 35 countries where street papers exist.

With this challenge, street paper organizations are proving themselves to be at the forefront of innovation within the media, publishing and social justice worlds they straddle. With the support of the International Network of Street Papers (INSP), they are adapting to the dangers of coronavirus and continuing to find ways to put money in vendors’ pockets and support their welfare in these challenging and strange times.

“We’ve been trying to help our members tackle these issues since it became clear that coronavirus was going to have major global consequences,” says INSP’s chief executive Maree Aldam, who is working from home like the rest of INSP’s Glasgow-based team. “Fortunately, our network consists of numerous robust organizations and countless talented, hard-working and innovative people who are constantly coming up with new ways to support the people they serve. The coronavirus outbreak has shown already that society’s most marginalized are at much greater risk. Those experiencing homelessness – and many street paper vendors do – are in a particularly precarious situation. Many cannot shelter or isolate, and often do not have easy access to hygiene products to protect themselves against contracting the virus. Our street papers have staff members dedicated to ensuring the welfare of vendors, and they are carrying on their work as best as the situation allows.”

In terms of cases and deaths, the virus is at different stages in various parts of the street paper network. In east Asia, the situation remains serious (with Korea and Japan looking to once again close borders and reinstate quarantine measures), but street papers are looking at what happens at the other end.

“The sale of the magazine on the street is still very difficult,” says Big Issue Korea director Byunghun Ahn. The Seoul-based magazine has started a monthly fund to provide for vendors to subsidize lost sales. “The situation around the virus is becoming more controlled, but everyone is still being careful. Vendors are advised not to move during the morning and evening rush hours. When our vendors and staff come to the office, we check their body temperature. It seems like Koreans are getting more used to this situation little by little. But it’s not yet possible to say that it is being ‘controlled’ because of the potential variables. It’s still a crisis.”

In Japan, where the magazine is being sold on the street for now, Big Issue vendors have been provided with food and drink via donations provided by supporters and readers through an Amazon wish list in lieu of stocks from food banks, on which they can no longer rely. In Osaka, they recorded the lowest sales in the street paper’s history, according to its editor Sayuri Kusama.

However, some of Big Issue Japan’s vendors are trying to remain positive. One vendor, Takuji Yoshitomi, in Osaka, said: “I’m trying to use this coronavirus situation as a positive. There are less people on the street, so it’s a chance to stand out. I'd like more people to be aware of vendors selling the magazine than usual. With this in mind, I managed to sell more than average today. But there are too many negatives. I fear this situation could push more people into poverty and homelessness.”

Even the precarious environment for street paper vendors in Japan, Korea and Taiwan seems a long way off for those in Europe, especially in Italy, where it remains grave. In Latin America and Africa, it hasn’t quite developed to that stage, though nations are already taking precautions. And in the US, some are expecting a slow governmental response to potentially have disastrous consequences. It is not an overstatement to suggest that every street paper across the world will be impacted by the effects of the virus.

“It’s clear that, in many of the countries where street papers are present, there are few safeguards in place even for small businesses and self-employed people to get through this,” says Aldam. “It’s not asking a lot for the system to catch those who are most vulnerable to the effects of this virus, but even in normal circumstances they are not sufficiently supported. Street papers, and the staff and organizations around them, as always, are working overtime to fill these gaps, ensuring that the people who rely on them stay safe, don’t fall through the cracks and can continue to earn an honest income.”

To do this, street papers, in countries where lockdown is imposed and social distancing measures enforced, have had to ensure that their vendors continue to earn money while unable to sell on the streets, and have been both employing novel ideas and ramping up previously held mechanisms to do this. While a small handful are still printing physical publications – trying to have them stocked in shops, like supermarkets, deemed essential and allowed to remain open – many have pivoted to digital copies that are delivered via subscriptions. A large number already had this availability, but they are now more important than ever, offering short-term solidarity subscriptions and annual deals. From The Big Issue and Big Issue North in the UK, to Italy’s Scarp de’ tenis, Sweden’s Faktum, and beyond to street papers in Finland, Mexico and the US, this has already proven to be a success.

Those who have dialed back producing full editions and moved their journalistic output totally online have turned to fundraising, calling for monetary donations to hardship funds and crowdfunders, or asking for food vouchers or other donations that will plug a cost gap for individuals that rely on their street paper income to survive. Social media has been a good gauge of the overwhelming responses. Liceulice’s pleas for support in Serbia caused their website to crash on the first night.

There have been forward-thinking and innovative calls to regular supporters. Several already have access to cashless less solutions, such as Venmo, which allow readers and supporters to direct funds straight to their local, familiar vendor. StreetWise, in Chicago, and Megaphone, in Vancouver and Victoria, have put up posters of vendors at their usual spot to encourage those who would usually pass by to remember their vendor during all of this. Of course, that becomes more difficult when people aren’t taking to the street, but it’s a good way to keep hold of something close to the personal part of buying a street paper. Distributing the money gathered from these alternative methods to vendors fairly and logistically is a challenge street papers across the board are facing up to as the current situation persists. Sales may be taking a hit as coronavirus locks everyone down and ruptures the global economy, but street papers are still working on overdrive to make sure that something approaching the $29.65 million put into vendors’ pockets every year continues.

And almost as important as providing an income for vendors are the myriad ways street paper organizations engage marginalized and under-privileged people in social projects and esteem building. This is continuing more creatively than ever: daily diaries from vendors to readers about life in the time of coronavirus, adopted by Strassenkreuzer in Nuremberg, L’Itinéraire in Montréal, Surprise in Switzerland, and elsewhere; needle exchanges and clothes banks in Slovenia by Kralji Ulice; maintenance of youth hostels for homeless vendors by Hus Forbi in Denmark; calls to donate games and books, and top ups for mobile phone plans by Shedia in Greece; providing hand sanitizer and other hygiene products to exercise thorough hand washing and other anti-coronavirus safeguards; and general communication, via calls, and Facebook and Whatsapp groups, to keep spirits up and remind vendors that they are not alone. Street papers the world over provide more than just a publication to sell. For some, it is solidarity; for others, it is family.

All images courtesy their respective street papers via the International Network of Street Papers (INSP).