11 minute read

Life After Service: Support For Homeless Veterans

from May 25 - 31, 2020

by Suzanne Hanney, Lee A. Holmes Contibuting

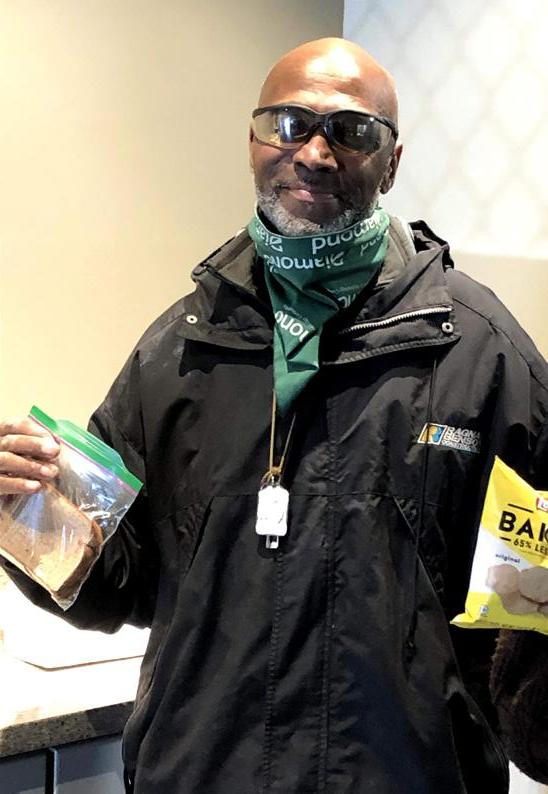

Conventional wisdom says that homeless veterans are recent combat survivors hiding out from society, but in Chicago, they are primarily African-American men over age 50 combatting structural poverty, racism and a lack of affordable housing.

The latest figures show 530 homeless veterans, of whom 417 are over age 45. The largest number (221) are age 56- 65, followed by 104 more age 46-55, and 92 over age 66. There are also 37 homeless women vets, both single and with children, typically in their 30s and 40s, post Persian Gulf-era. Only seven vets are age 18 to 25. The data comes from the Chicago Dashboard to End Homelessness, which showed similar figures in mid-December. Among 608 vets, 456 were over 45: 232 were age 56-65, 121 were 46 to 55 and 103 were over 66.

The reason Chicago’s Ending Veterans Homelessness Initiative (EVHI) can identify vets by age is a centralized database, with a single, “by-name” list, says Jessica Smith, senior program manager with CSH, which is the lead entity for the federally mandated coordinated entry system. EVHI’s centralized database has led to a 28 percent reduction in veterans experiencing homelessness since 2015, according to a June 2018 report by All Chicago: Making Homelessness History, which aligns the 91 agencies working to end homelessness in the city.

Suzanne Hanney

“EVHI can be credited with significant silo-busting,” says the report. That’s because the by-name list allows the veterans’ housing team -- which includes the mayor’s office, All Chicago, the Jesse Brown Veterans Administration medical center and staff from emergency shelters and other housing programs -- to discuss veterans across the board, even in programs that are not their own. In addition, funders provide housing resources that can be used by all agencies. Before, veterans were calling around to various programs on their own, trying to find the right fit.

Chicago veteran homelessness is not for lack of money, said Abraham House-el, program coordinator at Featherfist, which has five veterans’ programs in Chicago and whose program has the navigator for EVHI.

“One of the hardest things I do there at Featherfist is spend the money given to us by the Veterans Administration,” House-El said. “Everyone that’s in need of help doesn’t necessarily want it. Chronically homeless veterans that are sleeping around on the streets in tent cities, when our Featherfist folks approach them, they want nothing to do with our people. Sometimes we have three or four conversations before we can even get a name. Sometimes doing an assessment is next to impossible. There’s also a number of veterans that have mental health challenges that make it impossible on their own to get to organizations. That’s where a system navigator would come in.”

There have been increased capacities for navigators, who set up appointments for a vet to see a housing unit and who help with transportation, documents, emotional support and education around leasing an apartment, Smith said. Afterward, the navigator is someone the vet can call for support if there is an issue with the unit, or if they want to pursue other goals like employment training or financial literacy. “It’s not like we place them in a unit and are never heard from again,” she said. “The goal is always housing retention, identifying folks who need help before someone is at risk of housing loss.”

Chicago began conducting the federally mandated Point in Time (PIT) count each January, rather than every other year, in an effort to find homeless veterans. This year, the system was in place to identify vets; a couple of them were found during the count at shelters and connected to housing providers, Smith said. During the outdoor count, volunteers found a couple more people who identified as veterans. However, they did not meet VA eligibility guidelines: at least one day of active duty without a dishonorable discharge.

People can apply for a discharge status upgrade, particularly if the discharge was years ago, because the VA is now being more transparent, Smith said. In addition, people who served in the reserves or the National Guard but who are not called to active duty are ineligible for VA benefits, even though they count as veterans on the by-name list. Service providers seek civilian services for them, perhaps Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for aged or disabled people with little or no income; or Social Security Disability Income (SSDI), for people with more work history.

An exception, she said, will be the reservists who are now helping out with COVID-19, which counts as active duty.

The 450 to 600 average number of homeless veterans on Chicago’s official list is “just the tip of the iceberg,” says Marvin Gardner, vice commander of Veterans Strike Force (VSF), which he said is the only volunteer-led organization in a VA Hospital.

VSF, whose mission is “Vets Helping Vets” to become selfsupporting, staffs a table at the end of a long, skylit corridor four mornings a week at Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, 820 S. Damen Ave. Vets from all branches of the military stop by to talk and to pick up information on VA benefits and on city, county, state, federal and non-profit agencies that can help with emergency housing or even reentry for veterans who have been in prison.

“A lot of guys coulda seen something in the military, had an experience, don’t want to come into the VA for help, just live off the land,” Gardner said. “Some don’t even want benefits, they just want to be left alone because of how they were treated in the military, what they saw in active duty.”

Racial discrimination, he said, could have caused them to have received an “other than honorable” discharge, which affects their benefits. “A lot of them went there, went into combat, saw the damages of combat and wanted out, so [the military] said, ‘you want out, we are going to give you a discharge but put “personality disorder” on it so you can’t get benefits,’” Gardner said.

PTSD is also a factor; vets lock themselves into the basement, and their parents, who can’t deal with that, send them out onto the streets with no income and no benefits, he said.

Suzanne Hanney

“A lot do have PTSD,” Gardner said. “I was undiagnosed for at least 20 years. I didn’t even know I had suffered from it. I couldn’t fit into mainstream society. I couldn’t hold down a decent job, couldn’t provide for my family. I couldn’t sleep because I had dreams of what happened to me in the military.”

Gardner served in the Marine Corps from 1972 to 1975 during the Vietnam era in Thailand and off the coast of Cambodia. They were doing exercises and on standby for the rescue of civilians during the fall of Saigon in 1974.

Because he contemplated suicide, Gardner went to Jesse Brown VA from 7 a.m. until he went to work at 3 p.m., “just to feel safe and nobody hassling me. Luckily, I ran into these guys,” he said of VSF.

Unlike Vietnam, which was fought in the jungle, the Iraq War was guerrilla warfare in a city, he said.

Soon after the Iraq War started, one young Marine Corps returnee was real shaky. “He left an urban environment [in Iraq] and came back to one. Now he’s real leery about riding past dumpsters, riding down the street, period.”

The average vet stopping by the VSF table is 40 to 60 years old, although they see former service personnel as young as 20, Gardner said. Showers are available at Jesse Brown VA and VSF members often know homeless vets by name.

Military Sexual Trauma (MST) is another issue VSF hears about, Gardner said. Women volunteers will walk a female vet down the hall to hear her story more privately.

But MST doesn’t affect just women, said Reginald Lee, 58, who happened to stop at the VSF desk during our December interview. Lee served in the Navy starting with the Iranian Revolution of 1979. “I was on a ship and went out with officers. I had been warned but I thought it was a joke. They were married. They said, ‘I want to have sex with you.’ It was a macho thing, before ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’,” which allowed gays to serve in the military, even though it forced them into secrecy about their sexual orientation.

Lee said he was forced to sign papers that he was gay, a “personality disorder” on his discharge that affected his benefits. He had gone into the military to escape gangs in Chicago and didn’t seek VA help until he read a GQ magazine article on MST among men in September 2014.

He receives $771 in Supplemental Security Income (SSI). He had lived the last seven months in a transitional housing program with Thresholds, which provides services to people with mental health conditions. He said he was unsure if he was on the Chicago Dashboard list of homeless veterans, but he knew he was on a Chicago Housing Authority list.

On the other hand, Jeffrey Wade said his Marine Corps experience from 1976 to 1979 was the best of his life, followed by a literal crash in his civilian life. Wade, 62, attained the rank of lance corporal and visited Washington state, Alaska, Hong Kong, the Philippines and the Mariana Islands.

He worked in the pharmacy of a South Side hospital for 23 years and was in his senior year at the University of Illinois-Chicago when he was injured in an auto accident. Police were chasing another vehicle, which rear-ended his. Bending became difficult and he quit his job for fear of being fired. He also lost his dreams of continuing his education in architecture.

Wade lived in various shelters, including one in Lincoln Park he liked because of activities like concerts, plays and soccer games at Soldier Field. He later spent time in a program that was closed because of bedbugs, then at Hines VA Medical Center, because he had developed an addiction to pain pills following knee surgery related to the auto accident. He weaned himself off the pain medicine and lived with his daughter before getting into Catholic Charities’ St. Leo’s Ministries housing for veterans. Later, he met a lady and moved out. He was living with her on a Section 8 voucher in Auburn Park and receiving Social Security Disability Income (SSDI).

“Whatever services were out there to get me income, I used,” Wade said.

He started coming to a Jesse Brown VA Medical Center pain clinic four times a week in 2004 and now goes to a weekly psych clinic there because of depression over the losses the accident caused him. We met him at the VSF information table.

Walking through the doors of Jesse Brown VA Med Center “is like home,” he said. “We all have something in common. It’s like a brotherhood regardless of whether it’s males or females. It’s just an awesome experience to be around people who have been through what you’ve been through. The euphoria never fails me, the camaraderie. It’s a little like taking a pill, a psych pill.”

The VA has shifted its focus to housing veterans with barriers such as insufficient income, unemployablility, recent evictions, bad credit, mental or physical health challenges, or just inability to pay market rent. This is a population that is receiving VA or Social Security benefits and unlikely to see increased income anytime soon, House-El said. They’re rent-challenged, a population in their 50s and 60s – like more than half the veterans on Chicago’s Dashboard to End Homelessness. The VA formerly emphasized chronically homeless veterans, but vouchers have brought those numbers down, and the VA has found it difficult to process large enough numbers of them.

The VA introduced a “shallow subsidy” last October 1 for veterans who can’t get Section 8 vouchers in high-rent, gentrifying cities like Chicago, Honolulu, Seattle, New York City, five cities in California, and Washington, D.C. Since it began, the subsidy has assisted 53 veteran households in Chicago by providing 35 percent of the fair market rent; vets pay the remainder.

More people can be served with the shallow subsidy than with vouchers, especially in a gentrifying city, because the subsidy covers only 35 percent of housing rather than 80 percent for a conventional veterans’ voucher, House-El said. However, the subsidy covers only the cost of “light touch” case management, so it would not be appropriate for veterans who need more aggressive case management.

The key variable for the shallow subsidy, however, is income, Smith said. It prioritizes veterans who are seniors with an income at 30 to 50 percent of the Area Median Income, (AMI) or $18,720 to $31,200 for a single person. The vets are encouraged to receive supportive services through other programs, such as the Department of Labor’s Homeless Veterans Reintegration Program for job-related activities; Thresholds; Jesse Brown and Hines VA Medical Centers.

Both House-El and Smith remain optimistic that while the shallow subsidy may be just a test, it has lasting potential if it proves successful in getting veterans housed. “If the data suggest it’s one of the best things we could have done, that more veterans are staying housed, it’s a factor in eliminating veteran homelessness, it won’t go away,” House-El said.

Veteran homelessness is multifaceted, Smith said. It encompasses people with chronic physical or mental health issues, substance abuse, domestic violence, perhaps even the death of someone with whom they stayed. “A lot are in survival mode, some having to do with military time, some not. Being a veteran is just one piece of the puzzle. There’s a lot of other stuff going on that may impact housing status, not just poverty. There is the impact of institutional racism on our veterans and it’s important to capture the complexity of all these things. Not every landlord wants to work with vouchers. The reason we have not ended veteran homelessness is because of structural poverty, racism, and a lack of affordable housing in neighborhoods with access to stores, jobs and transportation.”

Suzanne Hanney