53 minute read

Structural Carbon

structural CARBON The SEI SE 2050 One-Year Anniversary By Chris Jeseritz, P.E., LEED AP BD+C

One year since the launch of the Structural Engineering Institute’s (SEI) Structural Engineers (SE) 2050 Commitment Program, 53 structural engineering firms have committed to embodied carbon neutrality by 2050. The Program’s overarching goal is to provide an accessible sustainability program for structural engineers that includes a commitment of active engagement in reducing the embodied carbon on projects and information sharing. The driver of these objectives is the collective objective of achieving net-zero carbon structures by 2050.

History

In 2016, the Carbon Leadership Forum (CLF) at the University of Washington created a working group to develop a data-driven commitment program for structural engineering firms to measure and work towards net-zero embodied carbon buildings. The CLF proposed their idea and the Structural Engineers 2050 Challenge framework to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) SEI Sustainability Committee. The ASCE SEI Sustainability Committee further developed the goals, requirements, and resources to make an official commitment program feasible and realistic to practicing structural engineers. After years of hard work by the ASCE SEI Sustainability Committee volunteers, the SEI SE 2050 Commitment Program was endorsed by SEI in late 2019 and launched to the public at Greenbuild 2020 as an SEI Program. The Program is run by volunteer members of the SE 2050 Subcommittee of the SEI Sustainability Committee.

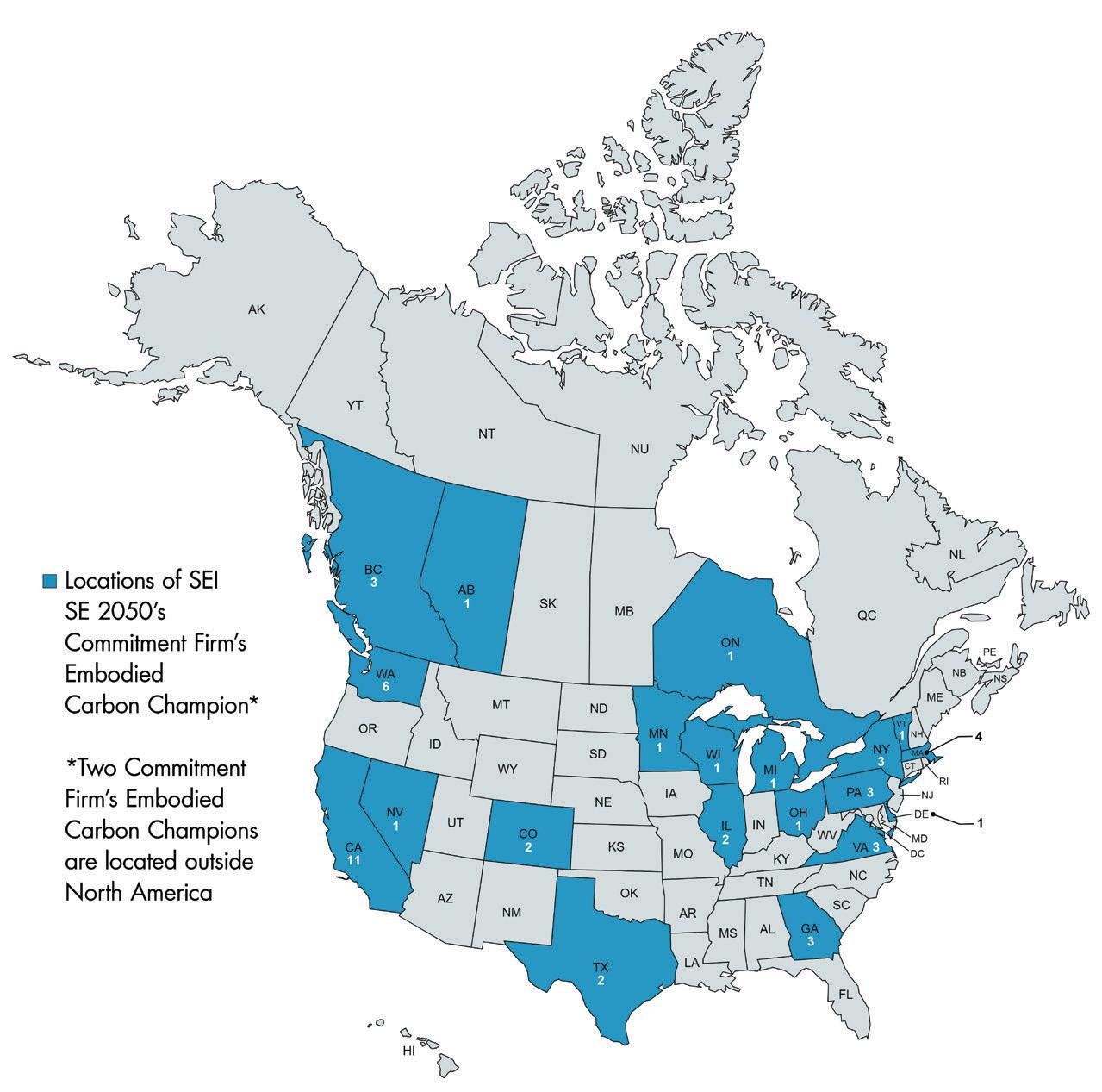

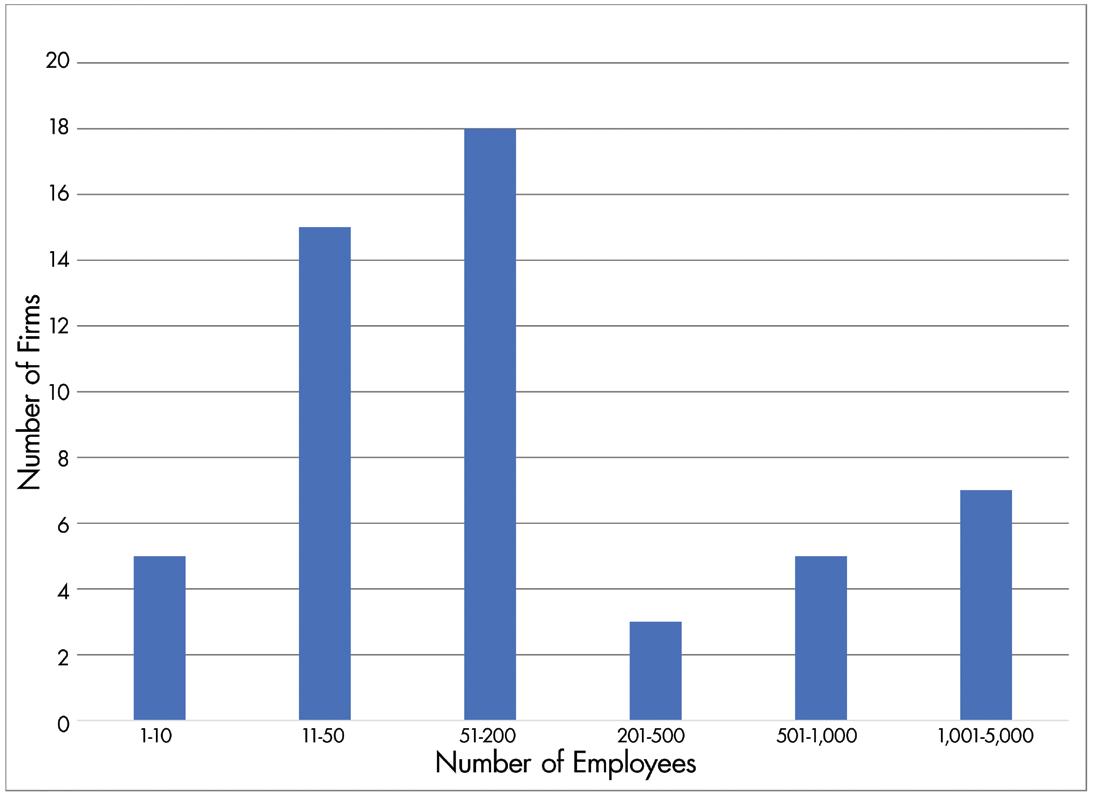

Figure 1. Distribution of SEI SE 2050 commitment firm’s embodied carbon champion in North America (Map created with mapchart.net). Committed Firms Support the Program Since the Program’s launch in October 2020, 53 firms have officially signed on to the SEI SE 2050 Commitment Program. From data submitted by committed firms, approximately 72 percent have no more than 200 employees, with 20 committed firms having 50 or fewer employees. The distribution of firm sizes illustrates that embodied carbon is a critical issue to firms of all sizes in the structural engineering community. The Chart displays the distribution of firm sizes committed to the SEI SE 2050 Commitment Program as of the beginning of August 2021.

Championing Carbon Reduction within the Firm

When a firm commits to the Program, they assign an employee to serve as an embodied carbon reduction champion and act as the main point of contact for the Committee and Program. Additional responsibilities of the champion include educating and advocating for embodied carbon reductions and ensuring the firm meets the yearly requirements of the Program. The state with the largest number of embodied carbon reduction champions is California, with eleven. Washington state follows with six and Massachusetts with four. In addition, two champions are located outside of North America. Figure 1 highlights in blue where the embodied carbon reduction champions

are located in North America and the number per state as of the beginning of August 2021.

A Roadmap to Reduce Carbon

Each committed fi rm must develop and submit an Embodied Carbon Action Plan (ECAP). e purpose of the ECAP is to articulate how a fi rm educates its staff , reports, documents reduction strategies, and advocates within the industry for and on embodied carbon. For companies wishing to simplify their ECAP submission, the SEI SE 2050 website contains an ECAP Google Form submission option allowing fi rms to streamline the creation of their ECAP. All committed fi rms’ ECAPs are publicly available and updated yearly. Of the 53 fi rms committed to the Program, 13 have submitted their fi rst-ever ECAP as of the beginning of August 2021. e SEI SE 2050 website lists the committed companies, the name of their internal embodied carbon reduction champion, the year the company committed to the Program, and a link to their ECAP. e SE 2050 Committee continuously updates this table as new fi rms commit and ECAPs are submitted. Submitting Data to the Program In addition to developing an ECAP, committed fi rms measure the embodied carbon of multiple projects’ structural systems and submit their fi ndings to the SE 2050 database. Firms commit to at least two project submissions per North American structural offi ce but need not exceed fi ve total projects per year. After months of development and testing, the database was offi cially launched on the SEI SE 2050 website in September 2021. A committed fi rm’s embodied carbon reduction champion can access the database from the website, add company users, and begin submitting embodied carbon data. e SE 2050 Committee has published a user guide to aid users in navigating and reporting their projects to the database. e information collected by the database includes project descriptors, structural system descriptors, and embodied carbon data. Figure 2 illustrates the diff erent parameters submitted for each project to the SEI SE 2050 database. After a suffi cient amount of data is collected, embodied carbon benchmarking for diff erent building types can begin to be formed. Resources for the Structural Engineer To help committed fi rms, the SE 2050 Subcommittee continues to add and update embodied carbon guidance on its website. Highlights of some of the currently released and upcoming resources include: 1) A guide to embodied carbon-related credits in green rating systems (USGBC LEED, Green Globes, Envision, etc.). is resource helps structural engineers learn and advocate for embodied carbon measuring and reduction credits depending on the green rating system a project is pursuing. 2) Embodied Carbon Intensity Diagrams showing the range of embodied carbon intensities associated with common

Figure 2. Data collected for the SEI SE 2050 database. structural fl oor systems. Updates will add more framing systems and bay layouts to those already available. Some of the upcoming embodied carbon intensity fl oor diagrams to be released include a reinforced concrete fl at plate, concrete pan joist, light-framed wood, and a hybrid mass timber/steel fl oor scheme. 3) Embodied Carbon Estimator (ECOM) for structural materials. Updates to the existing ECOM tool could include visual updates, report generation, and a user option to input custom global warming potential data from a productspecifi c Environmental Product Declaration (EPD). e Committee is also developing an ECOM guidance document and examples. 4) Case Studies. A list of project case studies discussing how embodied carbon was considered during design and construction has been added to the SE 2050 website for users looking for guidance or ideas on their projects. 5) Project specifi cations guidance. is document will provide guidance to structural engineers on incorporating diff erent embodied carbon reduction strategies into project specifi cations for multiple types of structural materials. In Closing Clients, government offi cials, and future engineers are interested and actively discussing embodied carbon. e SEI SE 2050 website and team are dedicated to helping structural engineers learn about and reduce embodied carbon. e structural engineering community has responded enthusiastically to the SEI SE 2050 Commitment Program and, within the fi rst year, the Program has picked up signifi cant momentum. e Program provides engineers a platform to play an active role in embodied carbon measurements and reduction strategies. e SE 2050 Committee is continually working to provide additional embodied carbon resources and Program improvements to meet this demand and enthusiasm to continue the impetus for the next year and beyond. If your fi rm is interested in learning more or joining the movement towards net-zero embodied carbon by 2050, please visit the SEI SE 2050 Program’s website: se2050.org to learn more.■ Chris Jeseritz is a Project Manager at PCS Structural Solutions in Seattle, WA, and a member of ASCE’s Structural Engineering Institute’s (SEI) Sustainability Committee and the SE 2050 Commitment Program. (cjeseritz@pcs-structural.com)

West Berkeley Medical Offi ce Building

Kaiser Permanente Brings Needed Medical Services and Creative Architecture to Its West Berkeley Neighborhood

By Nick Bucci, S.E., and Ryan Pintar, S.E.

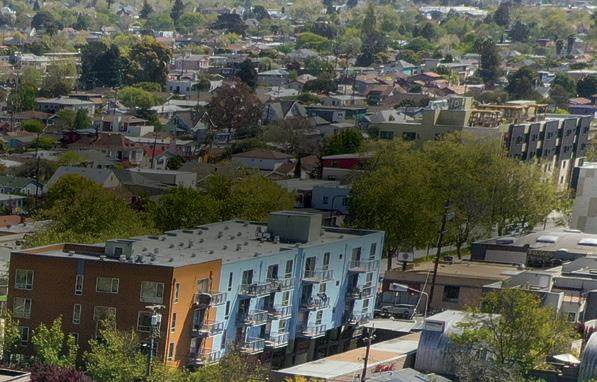

Figure 1. Aerial view of the building (looking southeast).

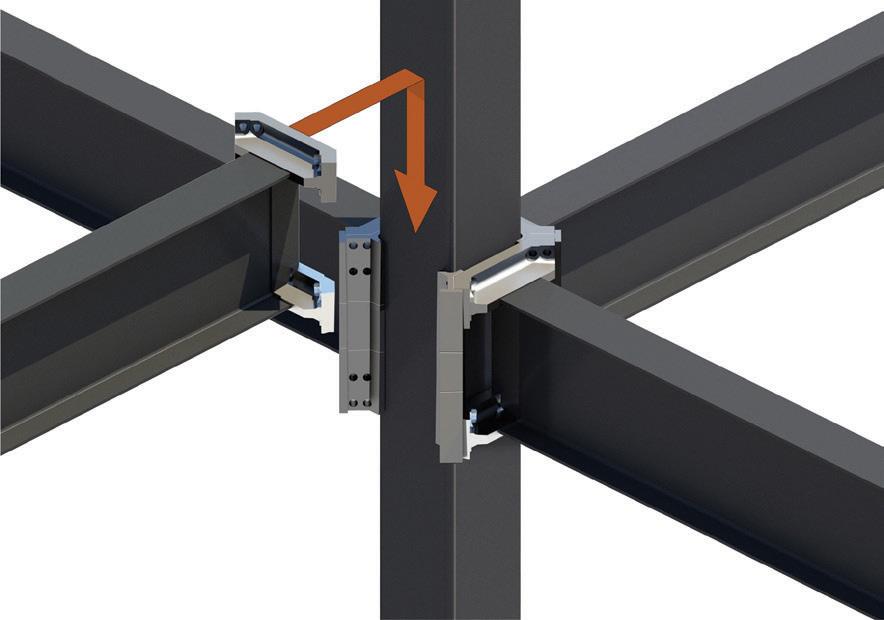

The new Kaiser Permanente (KP) medical offi ce building (MOB) in West Berkeley will provide critical medical services to the local community. e L-shaped 66,000-square-foot structure embraces the challenging small infi ll site with an integrated design that allows for open fl oor plates and a stunning architectural design. After studying diff erent structural schemes, the ConXtech steel space moment frame was chosen as the structural solution to maximize the fl exibility of the ground fl oor parking and embrace the architectural expression. e steel moment frame scheme allowed for improved seismic performance and allowed for shallow foundations.

Unique Design for a Unique Site

e building is located in Berkeley, west of San Pablo Boulevard and bounded by Parker and Tenth Streets. e site, with an existing corner property to remain, necessitated the new structure to be L-shaped in plan to maximize the building volume (Figure 1). e ground level predominantly consists of parking with some offi ce space and a small retail space along San Pablo Ave. e second and third fl oors have an open fl oor plan for medical offi ce use and four exterior terraces. e roof includes an enclosed penthouse and a screened-in mechanical space. Laboratory and medical offi ce structures are typically steel-framed and often use steel braced frames for seismic lateral resistance. For this project, steel braced frames were deemed impractical: at the ground fl oor, the brace locations would impact the ground fl oor parking and drive aisles, while at the upper levels, the skewed and twisting fl oor plan did not allow for the brace frames to stack vertically. A concrete structure with concrete Figure 2. ConXtech collar. shear walls was also considered but ruled out due to the shear wall’s impact on the ground fl oor parking and the lack of fl exibility for future tenant revisions. An additional complexity, there was no specifi c tenant on board during the project’s design phase. us, the building was designed on a specifi cation for future medical offi ce or light laboratory use. Designing a future medical offi ce building is challenging because these buildings have heavy mechanical and equipment demands that frequently add signifi cant loading to the structural framing, not to mention tenant-specifi c MEP systems and fl oor plate requirements. Based on the experience of the design team, it was determined that the structure would be steel-framed and use the ConXtech moment connections for the lateral system. e chosen system integrated with the unique architecture, tuck-under parking, and allowed for fl exibility with the future tenant needs. e property was sold to Kaiser Permanente after the design was fully permitted, putting the design fl exibility of the steel-framed structure to the test. Fortunately, the design team found that with careful planning and leveraging past experiences, the primary structure was designed to accommodate much of the new tenant’s needs without signifi cant structural revisions.

System Advantages

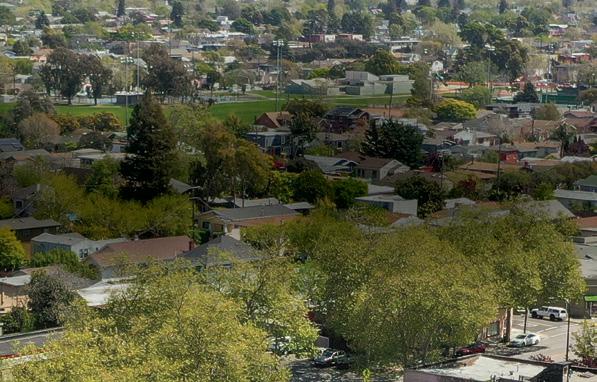

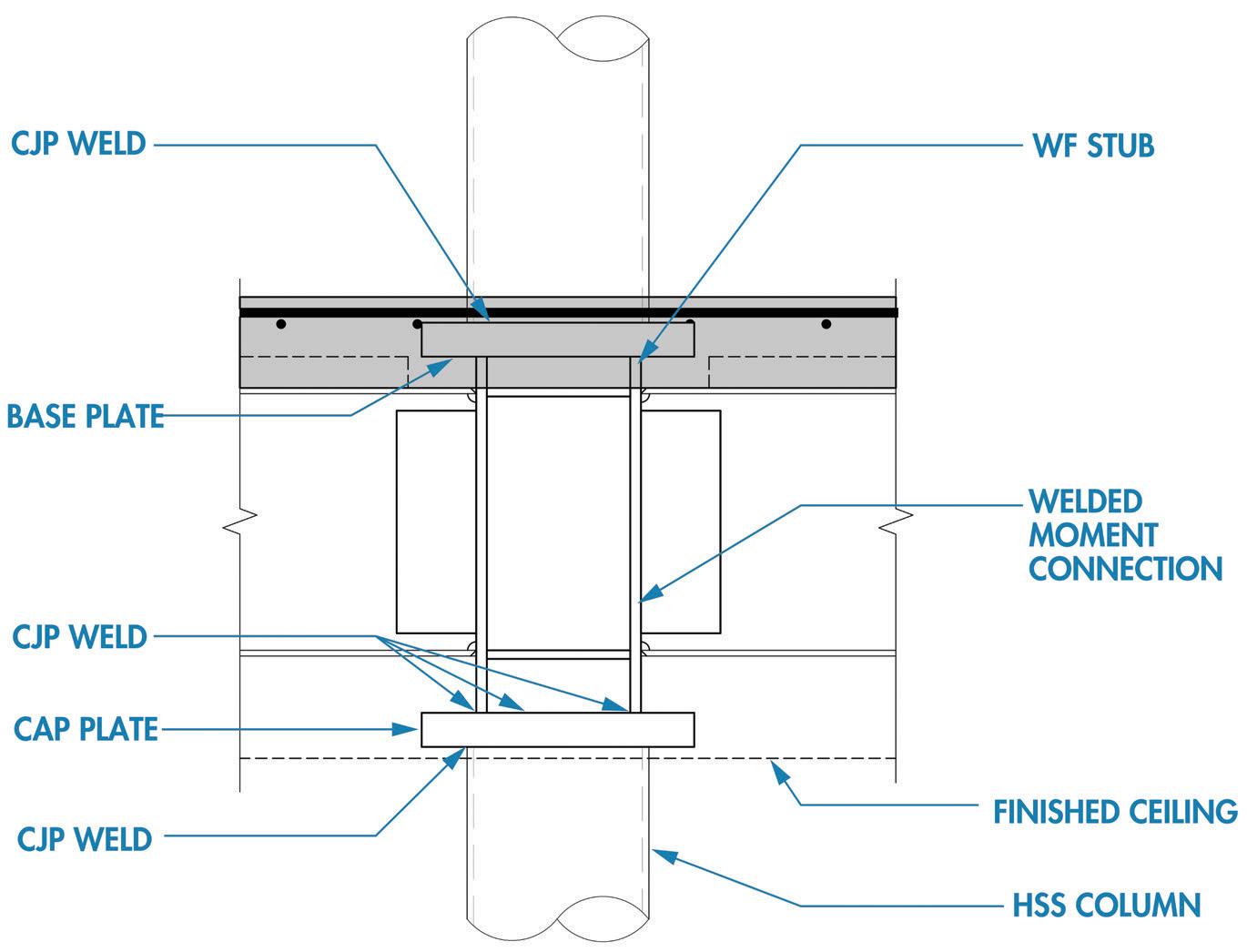

e ConXtech steel moment frame system features a proprietary interlocking beam-column connector prequalifi ed for use within ANSI/AISC 358, Prequalifi ed Connections for Special and Intermediate Steel Moment Frames for Seismic Applications. e moment frame columns are concrete-fi lled HSS shapes, and the beams are wide fl anges with reduced beam sections (RBS). Fully restrained beam connections are achieved through the ConX collar

Figure 3. ConXtech bi-axial bolted moment frame connection.

assemblies. Nesting components of the collar are robotically shop welded to the beams and columns, as shown in Figure 2 (page 27). Then, the beams are simply lowered and locked into position at the construction site, and pre-tensioned high-strength bolts are installed (Figure 3). The limited field welding with this system results in substantial time savings in the construction schedule. Furthermore, the ConXtech system allows for moment frame beams to skew in plan up to 15 degrees, facilitating the architectural expression along the west slab edge with minimal impacts to the lateral system design. The distributed bi-axial moment frame layout used with the ConXtech system integrated seamlessly into the typical framing, using 16-inch square-frame columns. Figure 3 shows a typical beam-column connection at a bi-axial moment frame. A diagram showing the distributed lateral system is shown in Figure 4. A conventional special moment frame with wide flange beams and columns works only in the strong direction of the column. It relies upon fewer deeper columns that can have a major impact on the usable space and architecture. The 16-inch square columns utilized in the ConXtech system helped maximize the parking area and make the project feasible. The building site consists of up to three feet of compressible fill with some potential for liquefaction settlement and moderate expansion potential; these soil conditions played a major role in determining the chosen structural system. The geotechnical recommendations allowed for the use of shallow spread footings with an allowable bearing pressure of 3,500 psf; however, the design team targeted an allowable gravity bearing pressure of approximately 1,600 psf to reduce the overall differential settlement. Combining the distributed ConXtech moment frame system and the lighter steel-framed structure allowed for the cost-effective use of conventional spread footings. A concrete structure at this site would have incurred additional costs for either soil improvements or a pile foundation system due to the heavier structure.

Specific Details

The design team collaborated with ConXtech throughout the design and construction of the structure. Like a conventional structure, Tipping Structural Engineers is SEOR for the structural design. ConXtech provides technical design support and serves as the steel subcontractor for the fabrication and erection of the primary steel frame. The building has a 14-foot floor-to-floor height, driven by the city’s zoning requirements for maximum building height. Frame beams are generally 21 inches deep at each level and, therefore, there is limited space below the framing for distributed MEP services. Thus, the SEOR coordinated with the architect and mechanical engineer to limit beam depths to 18 inches deep along major distribution trunks in the corridors to allow more room for mechanical services. The design team used ETABS to analyze the lateral force-resisting system and used RAM Structural System for the gravity framing analysis and design. Figure 5 shows the typical framing with the ConXtech system. Limiting the building’s torsion during a seismic event was another significant design consideration. Since the building is located in Seismic Design Category E, having an Extreme Torsional Irregularity is not permitted by ASCE 7, Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures, Chapter 12. Additionally, a design decision was made

to limit building torsion below the threshold for Torsional Irregularity to improve the structure’s overall seismic performance. Consideration of torsion also factored into the redundancy check. The structure is classified as an irregular structure, owing to the re-entrant corner. Sufficient moment frames were provided to prevent excessive torsion and improve the structure’s overall seismic performance to keep the redundancy factor at 1.0. The analysis showed that the seismic drift was reasonably uniform and less than 2 percent at the corners owing to the distributed lateral system shown in Figure 4. Base fixity is provided at the moment frame columns. With the distribution of loads facilitated by the space frame concept, it was possible to design fixed base columns using cast-in-place anchor rods with washer plates. The fabricator provided steel templates for aligning the anchor rods with the holes in the base plates, and setting the columns was quick and problem-free. In place of grade beams, it was decided to use the ground floor slab-on-grade to tie together the footings; construction cost and underground routing of utilities both played into this decision. The ground floor foundation and slab-on-grade design required extensive cross-disciplinary collaboration to accommodate the varied ground floor uses and finishes: office, sloped-to-drain parking area, retail, lobby, pavers, ADA access ramps, landscaping, and bioretention planters. A significant advantage of the ConXtech system is the expedited construction installation time and resulting construction schedule reduction. The primary steel frame was installed in approximately a week and a half, equating to about half the time of a conventional steel braced frame structure. The ConXtech system primarily relies upon a field-bolted system for gravity and moment frame connections to expedite the steel erection and field labor. ConXtech leverages a BIM Tekla model and a fully robotic fabrication system to ensure the necessary precision for the field-bolted system. The design team collaborated closely with ConXtech during the design and construction phases, including sharing Revit models to confirm dimensions and steel framing details.

Conclusion

The integrated structural design embraced the architecture and non-standard-shaped infill site to provide the West Berkeley community much-needed medical access. The ConXtech moment frame system proved to be the perfect solution for this project. It fits into the typical steel framing without compromising the architecture or usable space and allows for conventional steel framing and a shallow foundation system.■ Owner: Kaiser Permanente | Oakland, CA Structural Engineer: Tipping Structural Engineers | Berkeley, CA Architect: Gould Evans | San Francisco, CA General Contractor: XL Construction | Milpitas, CA

Nick Bucci is an Associate at Tipping Structural Engineers. (n.bucci@tippingstructural.com) Ryan Pintar formerly with Tipping Structural Engineers. (ryan@simplengi.com)

The Wachenheim

Science Center

WILLIAMS COLLEGE SCIENCE RENEWAL PROJECT

By Ron Blanchard, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, Michael A. Tecci, P.E., LEED Green Associate, and Julia K. Hogroian, P.E., LEED Green Associate

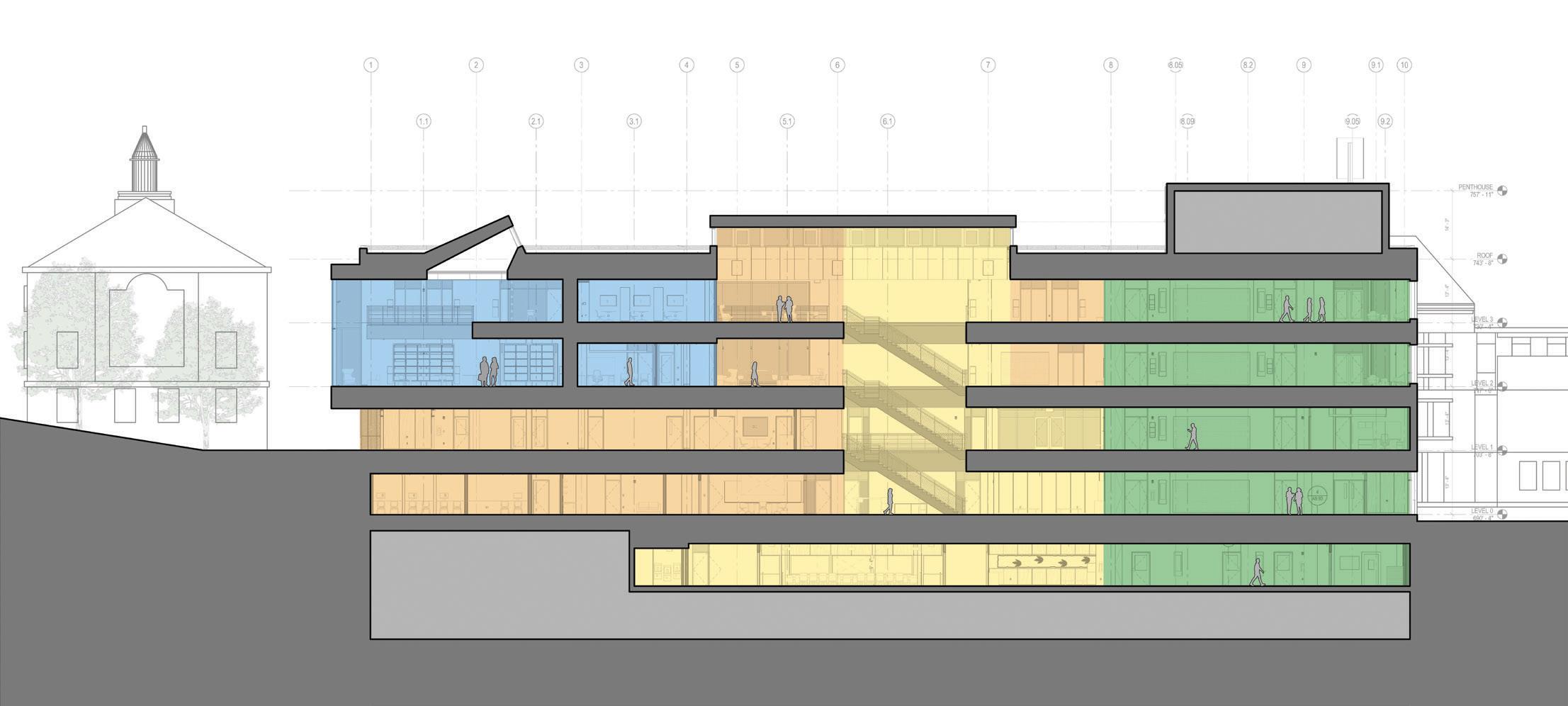

Exterior rendering of the Wachenheim Science Center from the northwest.

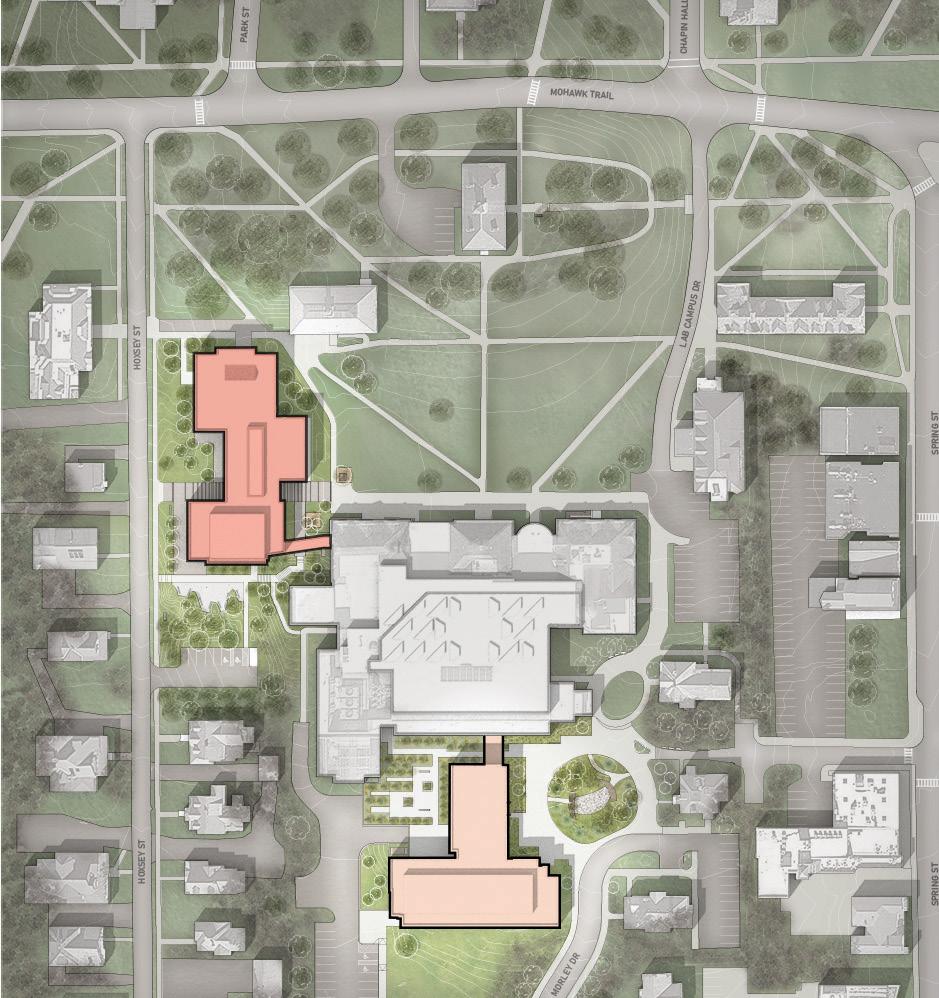

With tremendous growth in the sciences and the need for new research, teaching, and equipment space, Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, sought to expand its existing science center to serve the educational demands of the science departments and their students. Nestled within the Berkshire mountains, the original campus buildings are modestly scaled pavilions set in the landscape and defi ne a network of courtyards and outdoor spaces. While recent mega-building clusters were added to the campus, the college favored adding two modestly scaled buildings more in keeping with the original campus fabric over creating another singular megastructure. Th e buildings could still physically connect to the existing science center via bridge connections but would frame and shape the interconnected landscape that forms the spirit of the campus.

Payette Associates Inc., the architect and planner, and Simpson Gumpertz & Heger Inc. (SGH), the structural engineer, designed two buildings to revitalize the science campus. To the south, the Hopper Science Center, completed in 2018, provides new research space for the Biology, Chemistry, and Physics departments and houses new machine shops and an imaging facility. To the north, the Wachenheim Science Center was constructed on the old Bronfman Science Center site and provides research and teaching space for the Geosciences, Psychology, Mathematics, and Statistics departments. Th is article focuses on the structural design of the Wachenheim Science Center, completed in February 2021.

Design Overview

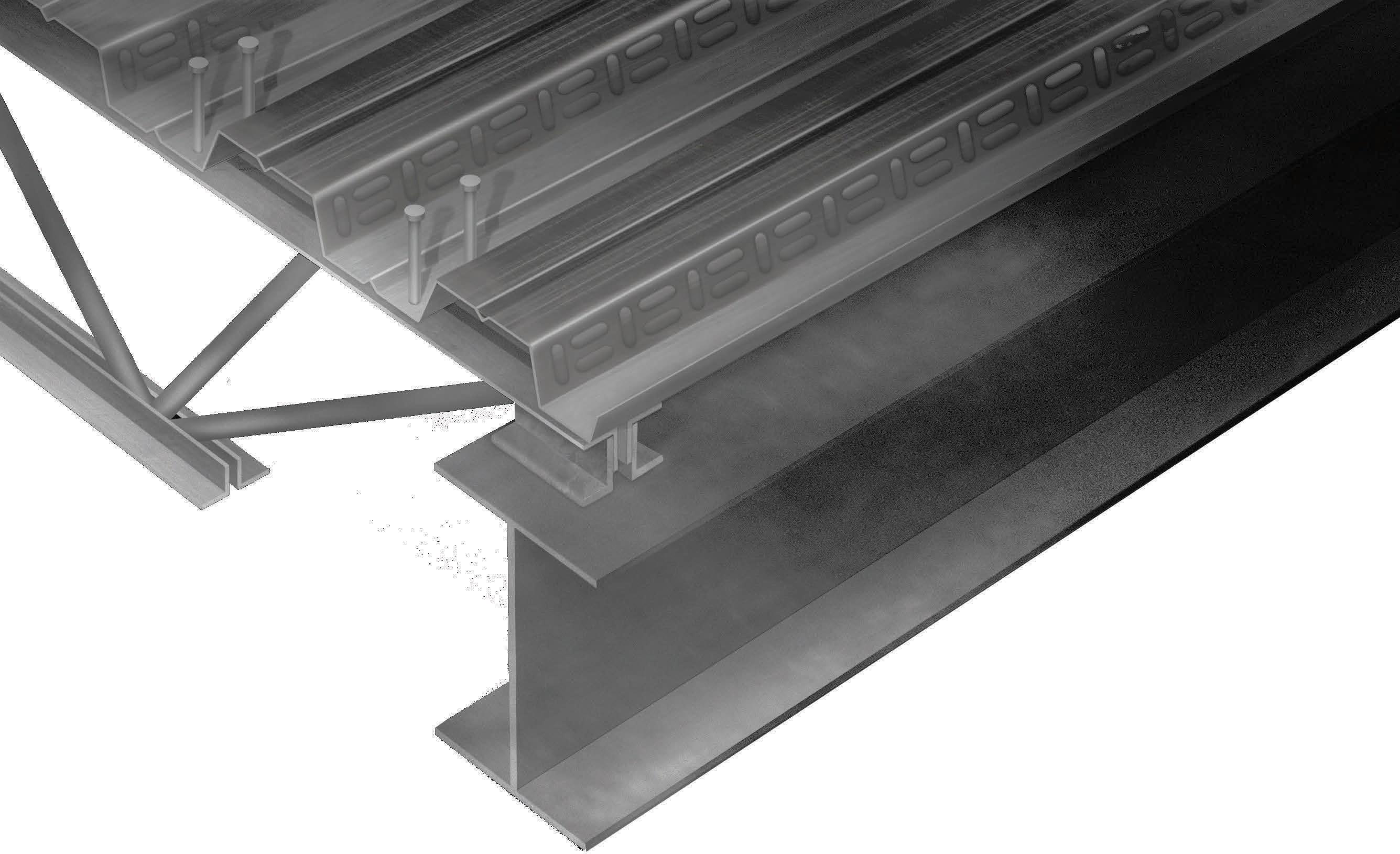

One of the design goals for the project was the ability to view the mountains from within the science quad. Th e building notches itself below grade into the bedrock to accomplish this goal. On this gradually sloping site, three and a half stories rise above grade while two and a half levels sit below. Th e foundation walls extend about forty feet below grade on the sides of the building, where the grade is the highest. Th e water table is approximately sixteen feet above the bottom of the basement slab elevation. Th e 26-inch-thick foundation walls and 4-foot-thick structural mat slab constitute the shell of the multi-story deep basement. Shear reinforcement ties in areas of high earth pressure shears are central to optimizing the volumes of wall concrete and reinforcement. The above-grade stories include classrooms, research laboratories, and offi ce spaces. Th ere is a small mechanical penthouse on a portion of the roof. Th e superstructure consists of structural steel framing acting compositely with a concrete slab on metal deck. A 4½-inch-thick reinforced

normal weight concrete slab on a 3-inch-deep metal deck achieves an uncoated two-hour fi re rating for the laboratory chemical control areas, improves vibration performance for microscopy work, and increases fl exibility for current and future fl oor penetrations typical of laboratory occupancies. ere are large areas of depressed slabs within the fl oorplates to accommodate a variety of fl oor coverings, including locally quarried stone tiles. Dropped steel beams, bolsters, and supplemental deck support angles enabled the complex layout and varying depths of the recesses. e architectural layout and the column grid often do not align from fl oor to fl oor because of the mixed-use of Wachenheim. Each level has a number of column transfers; some occur at Architecturally Exposed Structural Steel (AESS) round HSS columns. All connections and splices at these columns fi t within the depth of the ceiling cavity to maintain the clean HSS aesthetic. Moment frames provide the building’s lateral load resistance with minimal interference with the building’s complex program. Wind interstory drift control governs the design of the frames. Many of the moment frames have AESS round HSS columns. At the connections, the round columns transition to wide fl ange column stubs set within the ceiling depth to provide pre-qualifi ed beam-column moment connections and improved panel zone shear strength without compromising the aesthetics of the exposed columns.

Below Grade

Among the suite of below-grade classrooms is a 212-person auditorium that will be a valuable asset for the sciences. e auditorium fl oor is a sloping, formed stepped slab that spans to sloping reinforced concrete raker beams supported by concrete walls. Column transfers around the auditorium space allow unobstructed views. e design team studied various framing options’ varying the location and level of column transfers for the four fl oors above the auditorium. e adopted scheme has the roof and two stories frame to a column that bears on a 50-foot-long transfer girder at Level 2. Other 50-foot-long girders carry the loads of the roof of the auditorium and of Level 1 to perimeter columns and the foundation wall. is hybrid solution created an effi cient compromise of steel tonnage, serviceability, functionality, and constructability.

Partial site plan of Williams College depicting the Wachenheim Science Center to the north and the Hopper Science Center to the south.

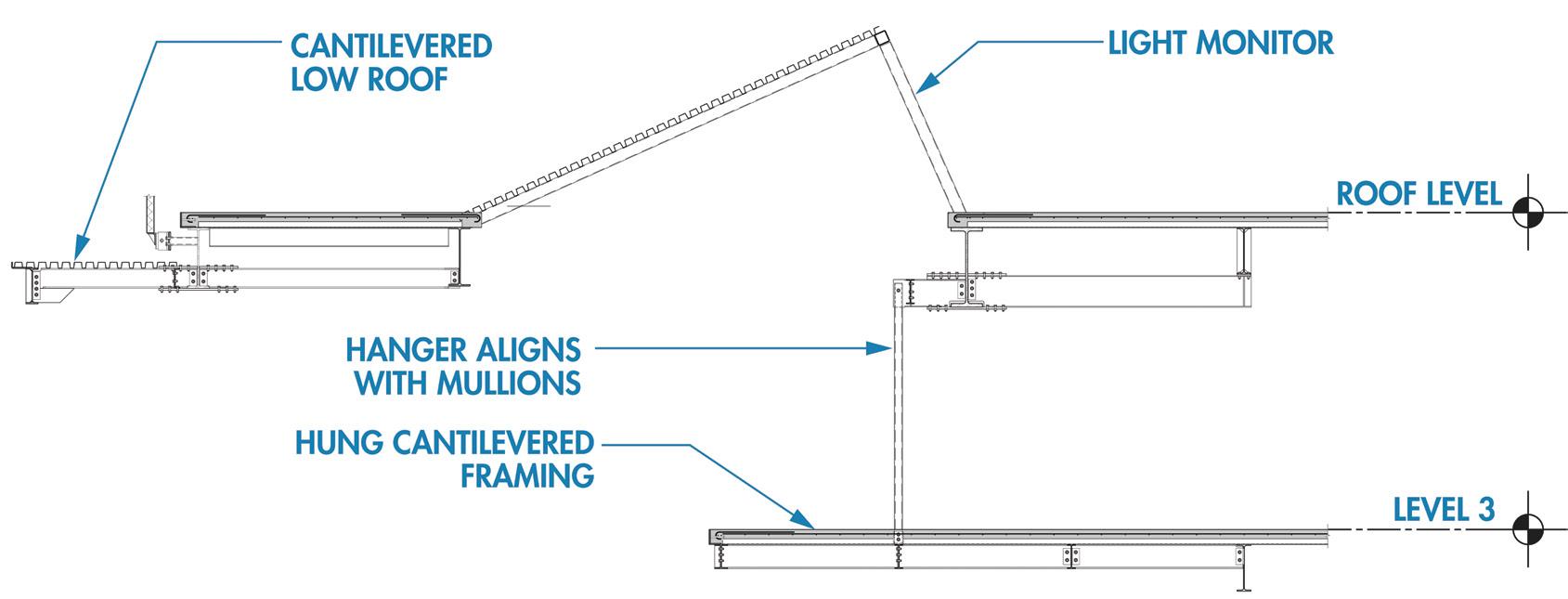

Creating “Lightness”

Some classrooms were forced below ground despite a desire for exterior views and natural light in all occupiable spaces. e design team added an at-grade exterior glass walk system on the east and west sides of the building to get daylight into these spaces. e glass walkway bears on sloping steel plates that frame between the fl oor framing and the foundation wall. A combination of tapered bolsters and concrete curbs support the sloped steel plates and glass structure. e building is organized by a main circulation spine, reinforced with a central staircase running alongside it, with hubs of departmental and student social spaces that pinwheel off . ese hubs of collaboration

space are what give the building its life force. In addition, each department has a double-height volume to mark the heart of the department, giving it an identity and a shared space for faculty and students to congregate. To create these living rooms, spaces needed to be open and column-free to be filled with tables, soft seating, chalk and marker boards, and to produce a collaborative, collegial, and academic environment. Two light monitors provide additional natural lighting, one of which is above the building’s central stair. The north light monitor aligns with the double-height atrium space in the Math Department. The double-height space creates an open atrium between Level 2 and the roof. The Level 3 floor framing hangs from the roof framing, which also supports the light monitor framing, to create additional column-free space on Level 2. For this intertwined area, floor vibration and deflection control the governing design criteria, requiring stiffening of Level 3 and the ultimate supports on the roof. The Psychology double-height atrium is approximately 30 feet by 30 feet in plan and has a double-height curtain wall on the north and east sides. Wide flange columns below Level 2 transition to a series of ganged small hollow structural steel tubes fitting within the backup framing for the brick piers. These eliminate the encroachment of a column cover in the corner of the space and minimize the visual impact of structural columns. The HSS columns bear on the stiffened slab edge at Level 2, run unbraced past Level 3, support the roof, and provide lateral support for the facade systems. There is a column-free entry in the southwest corner of the building. The design team studied various framing options to determine the most efficient system that could accomplish the design intent. Instead of a single massive column transfer girder at Level 1, the team opted for cantilevered floor framing at each level.

Partial plan of typical cantilever framing above the southwest entry.

Connectivity to Campus

While the Wachenheim is a standalone structure, it connects to the existing science center via a pedestrian bridge to provide a sheltered pathway during the Berkshire winters and maintain a physical connection to the rest of the sciences. The bridge is clad in a curtain wall and is structurally independent from the existing Thompson Biology center with an expansion joint between the structures. Directly below the bridge, there is a utility tunnel between the two buildings. The bridge springs off the new Wachenheim Center to a new column that bears on a pre-existing grade beam over the tunnel’s roof. The primary bridge gravity structure is on Level 3. Architecturally exposed plate columns behind the bridge curtain wall mullions act as hangers to support Level 2 and as columns to support the roof. The scheme minimizes the depth of structure and increases the transparency of the bridge at Level 2 and the roof. For wind and seismic loads, the bridge cantilevers horizontally off the Wachenheim center via diaphragm action of the floor and roof decks. The Hopper and Wachenheim Science Centers’ construction, two modestly sized buildings integrated into the existing science center complex via pedestrian bridges and tunnels, provides Williams College additional space and resources for various science departments. By focusing the Wachenheim Center on housing the Geosciences, Psychology, Mathematics, and Statistics Departments, the design team provided distinct educational and collaborative spaces tailored to the needs of each department. Close collaboration by the design team integrated the two new buildings with the campus by providing mixed programming and future flexibility in open, light-filled spaces.■

Ron Blanchard is a Senior Associate at Payette Associates Inc. (rblanchard@payette.com) Michael A. Tecci is a Senior Project Manager at Simpson Gumpertz & Heger Inc. (matecci@sgh.com) Julia K. Hogroian is a Project Consultant at Simpson Gumpertz & Heger Inc. (jkhogroian@sgh.com)

At an imposing 80-degree slope, the complex and unique canted brace highlights the slanted entry wall.

Structural By Thomas Kramer, P.E., S.E., Elizabeth Brack, P.E., S.E., Diana Gonzalez, EIT, and Geoff Leewaye, EIT Gymnastics IN THE TRANSPORTATION CENTER

The Transportation Center at Pima Community College’s Center of Excellence for Applied Technology is 43,000 square feet with a total of 27 work bays, including spaces for testing and diagnosis of electric vehicles, faculty offi ces, classrooms, a dynamometer room, equipment storage, and a large public entry. e unique utility of the building governed its placement, such as the clearance necessary for cars to drive around the lobby and into the work bays. In addition, the structural design focuses on responding to fl exibility and visibility, resulting in a state-of-the-art, hands-on learning environment refl ected in the vast amount of exposed steel. A high degree of coordination and unique framing concepts, which the team termed “structural gymnastics,” led to the project’s success. DLR Group provided planning, architecture, structural engineering, electrical engineering, interiors, and construction administration services for the Transportation Center.

Design Creativity

e structural system’s creative design focused on fl exibility and visibility, revealed in the exposed steel. Allowing daylight into the building was identifi ed as a critical characteristic of the project early in the design. In response, a spectacular 8.5-foot-wide skylight illuminates the high-volume work bay. Creativity in structural design responded to maintaining continuity in load transfer, refl ected by the unique stitched-together design at the high bay roof where the diaphragm was made discontinuous by the skylight. Finite element analysis using RAM Structural System was performed using semi-rigid diaphragms and analyzing the “stitching” as a horizontal truss. Transitioning from the ample auto bay space to the administration wing required transferring both the gravity and lateral loads through a non-orthogonal structural grid. e transition was accomplished

through a series of transfer girders and custom drag connections. e lateral load transfer at the interface of the high-volume work bay space and the adjacent two-story classroom building presented a unique challenge. e two-story classroom box is essentially skewed and overlapped into the high-volume work bay space. e lateral force-resisting systems were reimagined to ensure the fl exibility of the rooms at the interface of these two diff erent spaces. e solution resulted in a custom transfer girder connection to migrate the load from the classroom roof through a wide-fl ange girder rotated onto its weak axis and dragged to the high-volume work bay braced frames. Additionally, to create a light and airy shade structure, the large entry canopy was designed to tie into the lateral system of the main building, which eliminated the need for additional bracing. is was achieved with custom drag connections in each direction between the two structures.

Complex Criteria

Unique problems arose from the angular layout of the building, horizontally and vertically, that created framing challenges and required extensive detailing. e complex geometry involved a high degree of modeling and coordination for stud soffi t supports, exterior wall supports, skylight framing, and high/low roof framing. At an imposing 80-degree slope, the complex and unique canted brace highlights the slanted entry wall. e brace required an intricate degree of analysis due to the increased eccentricity. e 80-degree slope continues into the glass conference room that overlooks the Autolab and lobby. e large corner conference room with a fl oating eff ect is another design element that was crucial to the overall design of the building. e placement of columns and the addition of large transfer girders were crucial to delivering the intended visual impact. e tall exterior walls at the high-volume space exceeded 50 feet plus 11-foot cantilevered parapets. ese walls required a secondary framing system connected to the main steel frame system and increased the in-plane loading into the roof diaphragm and lateral system. In addition, the wide fl ange wind girts were orientated with the strong axis horizontally to provide greater strength and defl ection control to resist out-of-plane forces while also being in line with the primary structural framing.

8.5-foot-wide skylight illuminates the high-volume work bay.

Innovative Use of Materials

Innovation was seen in the application of the exterior panel façade system, resulting in a more cost-eff ective, lightweight, and easy to install solution. Integrating this system into the structural design involved challenges such as providing custom gravity supports and coordinating the lateral supports for the wall system with the main lateral resisting system – all of which are coplanar. e perimeter structure required a secondary analysis for out-of-plane lateral forces in conjunction with gravity and in-plane lateral forces to support the exterior wall system. e exterior translucent panel system was selected for its best-inindustry thermal performance and light transmission. e panels reduce solar heat gain, which drastically reduces the heating and cooling loads of the building. e diff used light transmission through the panels reduced lighting needs and provided electrical savings. Because the panels are prefabricated and lightweight, savings were

Hose reels cantilever from the 50-foot high roof.

also provided on transportation and installation time, approximately 2/3 less than a standard wall system. Structural cold-formed metal framing detailing at the exterior wall system allowed for elevated gravity support, material changes between translucent and insulated panels, and accommodated differential movement at the roof.

Design Efficiency

Ingenuity of design for efficiency was at the forefront of the design process from the beginning. Developing specific detailing in the Schematic Design stage minimized late and costly design changes later, which would have impeded the project’s success. Many design complexities required custom solutions, resolved through a high level of coordination and modeling to ensure the structural system was integrated with all other building systems. The transfer girder and steel framing plans were detailed early in the process to ensure smooth coordination and best-in-class design. The exterior façade and structural systems were selected and designed to provide long-term durability and speedy construction sequencing. The CMU walls at the bottom of the exterior walls provided a durable base necessary for the automotive work environment. The structural steel and paneled wall system above enabled quick installation while providing the sought-after thermal and lighting benefits during the life of the building.

Constructability

Challenges related to constructability were solved using a high degree of coordination and validation in framing to ensure that the structural systems worked within the angular layouts of the building. The structural system had to allow for the movement of vehicles through the space, which meant coordination of column locations, providing cantilevered floor systems, and providing moment frames to guarantee open access. The atypical requirements of the automotive equipment meant making sure these systems were accounted for early in design to avoid conflicts during construction. The foundations in the Autolab were coordinated to prevent clashes with under-slab exhaust systems and integrated mechanical systems. Moreover, most mechanical units were installed on the roof of the large auto bay space, and ducts then serviced the lower volume classroom spaces. To access the classroom spaces, however, the ducts had to squeeze through the large transfer girders at the interface of the two spaces, leaving little to no room for error. The team used Navisworks clash detection to identify structural and mechanical issues before they happened in the field to aid in coordination and field challenges when installing mechanical systems. Hose reels that hung from high bay roof structure required custom detailing and an understanding of construction sequencing. In a standard automotive service area, hose reels are hung from the ceiling, typically only 12 feet in height. With a roof that went as high as 50 feet, steel framing had to cantilever down while still meeting equipment deflection limits and providing adequate clearance below. The overall result of the Transportation Center is a bright, open space that is highly functional to its occupants. The seamless transition into different spaces with geometric peculiarities is a true testament to the team’s early vision and high degree of coordination.■

All authors are with DLR Group. Thomas Kramer is a Project Manager. (tkramer@dlrgroup.com) Elizabeth Brack is a Project Engineer. (ebrack@dlrgroup.com) Diana Gonzalez is a Project Engineer. (dgonzalez@dlrgroup.com) Geoff Leewaye is a Project Engineer. (gleewaye@dlrgroup.com) Project Team

Owner: Pima Community College Structural Engineer and Architect: DLR Group Contractor: Chasse Building Team Structural Software: RAM Structural Systems,

RAM Connection, RAM Elements, RAM SBeam,

Enercalc, Navisworks

The joist that redefined floor systems.

Vulcraft CJ-Series composite steel joists are causing designers to rethink the way multi-story floor systems are designed. Our CJSeries floor system is engineered to support the longest spans possible, reduce floor-to-floor height, and provide maximum flexibility for MEP layout – all of which helps to reduce costs.

Our CJ-Series composite steel joists give you:

• More connection options to reduce floor-to-floor height and mitigate vibration. • Lighter weight and more efficient joist design for greater cost savings. • Greater joist spacing options for fewer joists to support the floor. • More flexibility with MEP layout with the open web design.

Simply put, Vulcraft’s CJ-Series joists have redefined multi-story floor systems.

Flush Frame Connections help mitigate vibration.

Powerful Partnerships. Powerful Results. Vierendeel Openings simplify MEP layout.

Part 3: Structural Investigations

By D. Matthew Stuart, P.E., S.E., P.Eng, F.ASCE, F.SEI, A.NAFE, SECB

This four-part series discusses the adaptive reuse of the Witherspoon Building in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Part 1, STRUCTURE, September 2021, Part 2, October 2021). Part 3 continues the discussion of the structural investigations – specifically the main roof and original mechanical penthouse – conducted to understand the existing structure better. Numbered photos are provided in the print version of the articles; lettered photos are provided only within the online versions of the articles.

Structural Investigations (continued)

Results of the main roof and original mechanical penthouse investigation indicated that the high penthouse roof had sufficient reserve load-carrying capacity to support proposed new mechanical rooftop units (RTUs) that serve the residential units. However, it was necessary to design steel beam support dunnage that clear spanned between the penthouse columns to prevent imposing any load directly on the book tiles and bulb tees (Figure K, online). The increased lateral load on the penthouse due to the raised RTUs also required additional vertical X-bracing (Figure 11) to be installed inside the penthouse

Figure 12. Northeast corner of passenger elevator penthouse at southwest corner of new RTU dunnage.

between the existing cast-iron columns and below the high roof beams. In addition, the installation of the X-brace connections was designed to avoid welding to the cast-iron columns by only connecting to the existing beams. During the project’s construction phase, direct tension testing of the penthouse X-brace rods was conducted. This was to ensure correct rod pre-tensioning via turnbuckle rotation was performed without yielding the ½-inchdiameter rods. In addition, during the high roof dunnage construction, it was necessary to remove some of the brick masonry façade wall at the northeast corner of the passenger elevator machine room penthouse to access the existing column so that it could support the southwest corner of the dunnage. After removal of the brick, it was discovered that the steel wide flange column that supported the penthouse roof had been spliced on top of an existing Gray column (Figure 12). In addition, corrosion of both the wide flange column and Gray column had occurred due to moisture infiltration from a failed penthouse parapet coping above. The damage was corrected by cleaning the steel of all corrosion by-products to determine the extent of section loss, adding welded headed studs to the column sections, then encasing the members in a reinforced concrete pilaster that recreated the masonry corner of the penthouse. Encasing the steel columns in concrete strengthened them to offset the loss of section and protected the steel from further corrosion. As a part of the investigation, it was also discovered that a few of the mechanical penthouse cast-iron columns were cracked at the

beam web connection clip extensions that had been cast with the original pipe section (Figure 13). The source of the cracking was unclear; however, it was assumed that the cracks occurred during the original handling and erection of the columns due to the brittle nature of cast iron. It also appeared that the clips were intended for lateral support of the beams during erection only and served no actual structural function in the as-built condition. Nevertheless, new bracing angles were added between the affected beams and adjacent orthogonally framed beams at the same column. Investigation results also made it necessary to design and detail the exterior assembly space as steel dunnage framing that spanned between the existing main building columns. However, reinforcing the lateral resisting system between the main roof and 11th floor was unnecessary because the increase in horizontal forces was determined to be less than 10% of the existing lateral loads at the roof level, as allowed by the International Existing Building Code (IEBC). To avoid imposing assembly space dunnage loads on the existing clear span roof trusses, it was necessary to extend new columns up from the top of the 11th-floor main building columns to create rigid frames that in turn provided a platform for additional columns, which straddled each side of a truss and supported the new rooftop dunnage framing (Figure L, online). Also, a subsequent additional investigation was completed at the main roof, 11th floor, and ceiling framing impacted by the proposed new elevator and stair penthouses, which confirmed the original roof investigation conclusions. Unfortunately, the design associated with all of the above, except for the RTU dunnage, was excluded from the project due to the high cost of the proposed renovations. proposed new chillers indicated that, in general, the existing exposed framing could support the new equipment once the existing cooling towers were removed and the existing steel was cleaned and repainted to prevent further corrosion. However, unsafe structural conditions were observed at the two easternmost column post supports, immediately adjacent to the building’s edge, due to excessive steel corrosion and almost complete section loss (Figure 14). The building owner was immediately notified of the unsafe conditions; however, the conditions were not corrected until much later in the project when similar corrosion was observed at all other dunnage column supports. In the interim, the existing cooling tower equipment was removed from the dunnage. Damaged columns were either replaced with new steel HSS columns or, if the corrosion was not

Figure 13. Cracked beam-web connection clip at too severe, encased in a reinforced concrete a penthouse cast-iron column. plinth that included headed studs welded to the original steel column. After the equipment was removed, the steel dunnage was cleaned and assessed. This resulted in the discovery that section loss due to corrosion exceeded 5% of the original area; therefore, it was necessary to weld reinforcing plates to the wide flange members to offset cross-sectional area loss. It was also necessary to design new steel grillage framing on top of the existing dunnage to marry the new chiller equipment to the existing framing footprint. New open steel grating catwalks were also provided, along with new support framing for the chiller piping between the existing dunnage and mechanical penthouse as required to avoid placing excessive pipe loads on the main roof framing below. The completed chiller dunnage and pipe support framing is shown in Figure M (online). Mechanical Penthouse Figure 14. Corrosion and excessive section loss at an existing cooling tower steel dunnage column support.

Mechanical Penthouse and Cooling Tower Dunnage

Both the existing mechanical penthouse and cooling tower dunnage had been constructed well after the original building existed. The purpose of their structural investigations was to determine the ability of the same two structures to support the proposed new mechanical equipment and chillers, respectively. The investigation was required because there were no existing drawings available for either structure. Investigation findings are provided below and were based on steel coupon test results of a typical penthouse floor beam and roof joist of approximately 40 ksi and 50 ksi, respectively. Cooling Tower Dunnage

In general, the condition of the existing penthouse structure was fair; however, isolated cracking of the perimeter concrete base wall and moderate corrosion of the interior floor and roof framing were observed. Further, severe corrosion at the exterior steel stair stringers (Figure N, online) between the penthouse and main roof, which had resulted in complete loss of section in some areas, required that the damaged area of the stringer be demolished and replaced. In addition, isolated spalling of the floor slab soffit was also observed. Although the existing 6-inch concrete floor slab capacity could not be accurately determined due to a lack of information concerning internal reinforcing, it was confirmed that the existing steel floor beams had a superimposed, service uniform load-carrying capacity of 100 psf. The open web steel roof joists were determined to have a

Figure 15. Partially erected strengthening of the existing freight elevator penthouse.

load-carrying capacity of 16 psf in addition to all existing dead loads associated with the roof structure, roofing, and minimum roof live load of 20 psf. The available capacity of the existing floor was considerably less than that imposed by the new mechanical equipment. As a result, it was necessary to design an independent, steel beam dunnage frame erected immediately above the existing penthouse floor slab to support the new equipment. The new framing clear-spanned between existing perimeter penthouse columns, which could support the new loads, including the existing main building columns below. It was also determined that the existing roof framing had adequate capacity to support the suspended mechanical piping associated with the new penthouse equipment.

Freight Elevator

Machine Room Penthouse

The existing freight elevator penthouse floor framing consisted of three 15-inch-deep steel wide flange blocking beams that directly supported the elevator machine loads. The blocking beams were supported by W14 machine beams that were in turn supported by W16 beams that spanned east and west between W24 girders. The W24 girders were supported by two perimeter building columns at the north exterior side of the penthouse. One framed into the northernmost roof truss at the south end of the W24 girders, while the other framed into an interior main building column. The penthouse floor, also supported by the beams described above, consisted of a solid concrete slab. The floor beam framing also supported a perimeter, multi-wythe brick façade wall, a steel-framed roof, a solid concrete roof slab, and the elevator hoist beams. The existing Otis elevator machinery before its removal is shown in Figure O (online). Penthouse framing analysis included determining the impact of the new loading, provided by the elevator manufacturer, on the moment and shear capacity of the existing framing described above. In addition, the deflection of the framing members was assessed based on the criteria of American Society of Mechanical Engineers A17.1 (ASME A17.1). Analysis results, which were based on a steel coupon test from an existing penthouse roof hoist beam that revealed a yield strength of approximately 47 ksi, indicated that the moment and shear capacities of the 15-inch blocking beams, W14s, W16s, and W24 girders were adequate to support the proposed new elevator loads. As a result, it was also assumed that the existing beam end connections were likewise adequate for the new loading. Based on ASME A17.1 Section 2.9.5, allowable deflections of elevator equipment support beams must be less than span/1666. While the calculated deflections of the blocking beams and W14 beams were less than this same amount due to the proposed new equipment, deflection of the W16 beams and W24 girders would be more than the same allowable deflection and were therefore not capable of safely supporting the proposed new loads. As a result, structural reinforcing was developed for the W16s and W24s. Strengthening the W16 and W24 beams involved installing vertical steel members diagonally between the floor beams and the roof beams above to create story-high trusses (Figure 15). In addition, due to the increase in the minimum-code roof snow load requirements since the existing Otis elevator was installed, the roof truss that supported the W24 penthouse floor girder had to be re-supported with an additional column between the top of an interior 11th floor column and the bottom chord of the existing truss to reduce the span. Shaft Vertical Rail Supports

This investigation did not include an analysis of the existing vertical cab guide rails or counterweight system because they were considered part of the operating equipment for which the elevator manufacturer was responsible. Unlike the vertical cab guide rails, it was also determined that the counterweight system did not impose any additional load on the existing structural supports located within the shaft. Therefore, neither the vertical guide rails nor the counterweight system was included in the investigation and analysis of the existing internal shaft support framing and related floor framing supports. The primary deficiency documented in the shaft as a result of the investigation was the existing connections between the vertical guide rails and the existing horizontal support members at each floor level. Further, it was determined that the existing horizontal support beams, spanning north and south at the east and west guide rails, were also not capable of supporting the new imposed loads. As a result, new rail support beams were designed and installed with the existing supports abandoned in place. However, the related floor support beams located around the perimeter of the shaft could support the new loads. The elevator manufacturer also provided new clamping bolt connections between the existing rails and the new supports and installed a properly-sized bearing plate at the base of the rails on top of the existing concrete pit slab. Part 4 of this series continues the structural investigation discussion, including column capacities and connections, new floor openings, and other renovation-related issues.■

D. Matthew Stuart is Senior Structural Engineer at Pennoni Associates Inc. in Philadelphia, PA. (mstuart@pennoni.com)

state at City Creek95 Salt Lake City, UT By Mark Sarkisian, S.E., Peter Lee, S.E., Rupa Garai, S.E., Jiejing Zhou, P.E., Alex Zha, and Jaskanwal Chhabra, Ph.D.

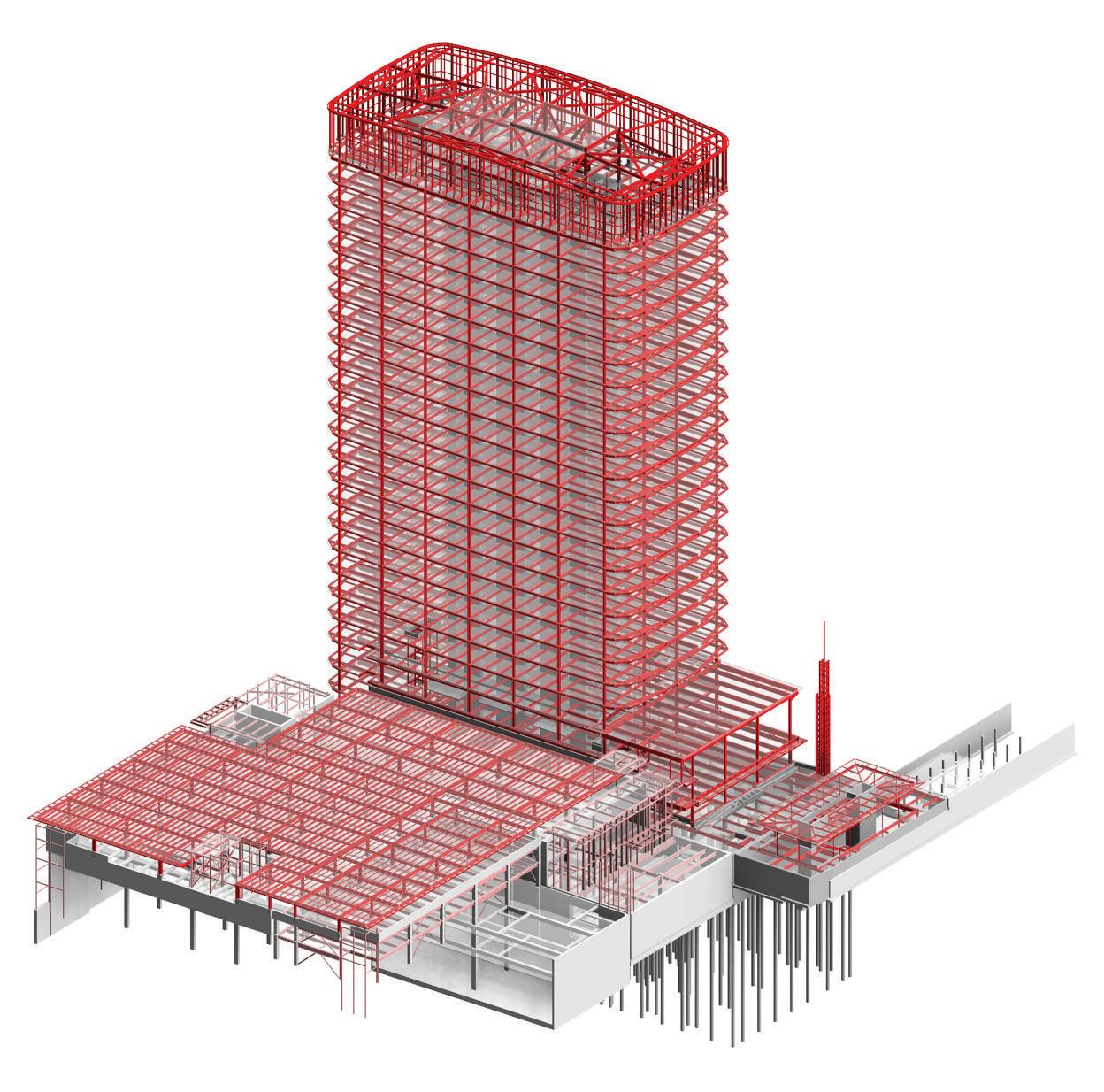

The new 95 State offi ce and mixed-use facility consists of a 25-story Class A tower with a 5-story podium ecclesiastical meeting house totaling 640,740 square feet. e building is located in the heart of downtown Salt Lake City, Utah. e project is being developed by City Creek Reserve Inc. with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, architect and structural engineer, and Okland Construction as the general contractor. It is scheduled for completion in late 2021. e integrated urban design of multiple project components includes a complete rehab of the interconnecting pavilion and tunnel under State Street, connects 95 State to Salt Lake’s City Creek Center, and provides connections to neighboring Harmons retail and parking with a new solar canopy. With a client and owner team interested in the long-term performance of the facility located in a region of high seismicity and close to an active segment of Utah’s Wasatch Fault zone, SOM’s structural engineering design team responded to the design challenges of the new 392-foot-tall tower constrained on a narrow corner site using state-of-the-art performance-based seismic design methodologies and standards. Figure 1 shows 95 State from the south nearing completion.

Tower Structural Systems

Designed in conformance with the 2015 International Building Code (IBC) with State of Utah 2016 Construction Code Amendments HB310, the 95 State tower and podium structure is assigned a Risk Category III per the occupancy load limits of 2015 IBC Table 1604.5. e tower superstructure uses reinforced concrete core walls as the seismic-forceresisting system extending to an overall building height of approximately 392 feet above adjacent grade with a one-level below-grade basement on the south. e site slopes up to the north approximately 15 feet along State Street, encompassing a second basement below Level 2 on the north. e height exceeds the code-prescribed height limit of 240 feet for the core-wall-only system. erefore, the design uses a “non-prescriptive” building code design approach using an “alternate procedure” per 2015 IBC Section 104.11. e superstructure is designed based on the acceptance criteria provisions of the 2015 IBC and ASCE 7-16 standard, Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures, Section 12.2.1.1 using PEER TBI v.2.03 (2017), Guidelines for Performance-Based Seismic Design of Tall Buildings. e ASCE 7-16 standard was adopted as a project-specifi c exception to the building code as recommended by PEER TBI v.2.03 Section 1.3. An independent structural design review was provided in conformance with ASCE 7-16 Sections 12.2.1.1 and 16.5 as approved by the authority having jurisdiction, the Salt Lake City Corporation.

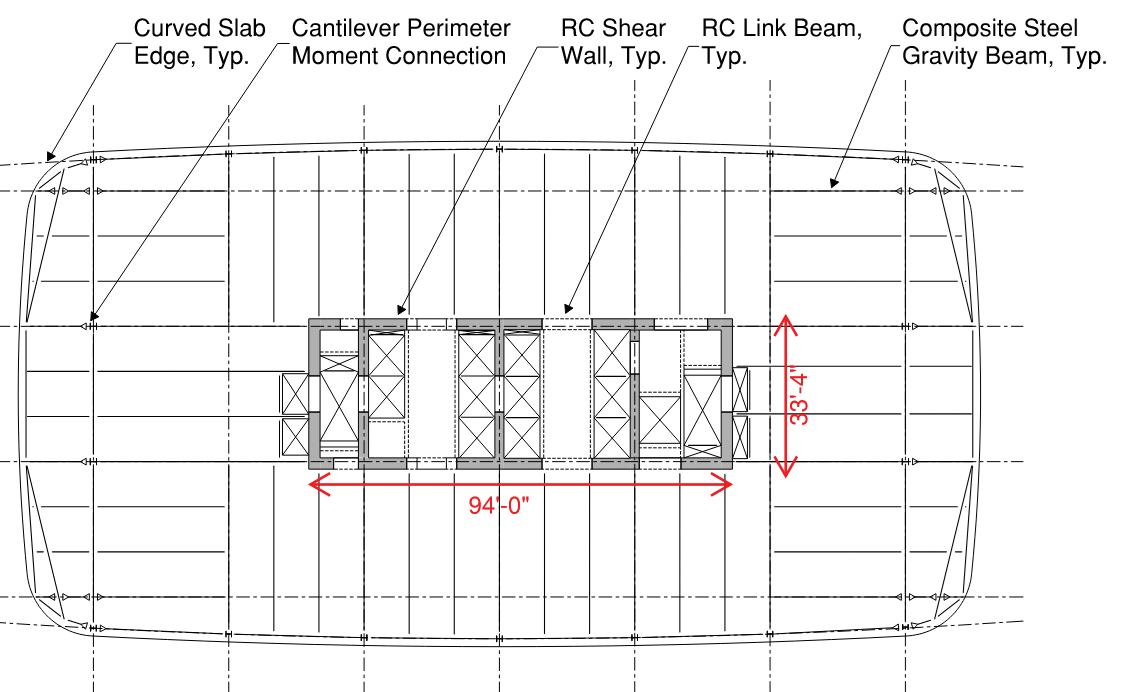

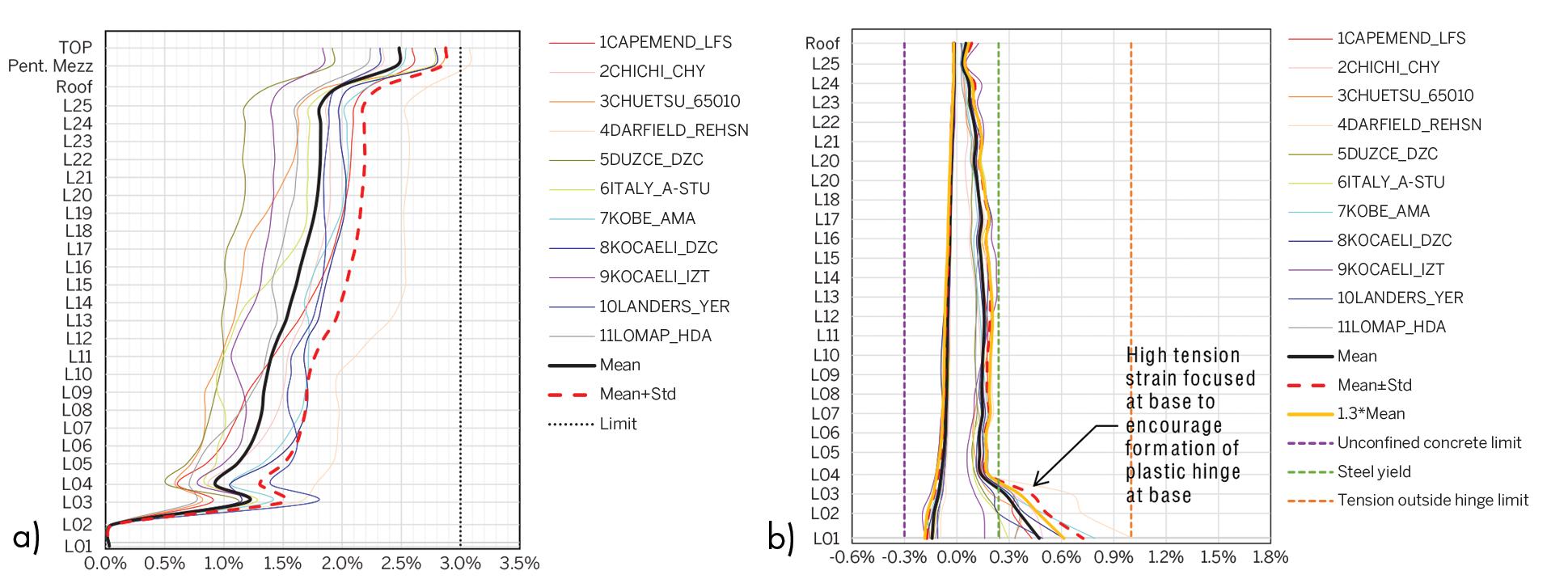

e lateral seismic-force-resisting system consists of special ductile reinforced concrete core shear walls and coupling beam construction extending from a pile and pile cap supported deep foundation system to the penthouse roof at Level 26. e slender core wall depth in the east-west direction is 33 feet, 4 inches, with an aspect ratio of 11.8. Core shear walls range from 24 to 30 inches thick with concrete compressive strength of 8,000 psi. Shear wall thicknesses are constant over the full height of core walls. e shear wall core is interconnected with ductile reinforced coupling beams at openings required for doorways and corridors. Additional openings with coupling beams were introduced to increase seismic inelastic energy dissipation. At Level 26 (El. +356.5 feet), the 2-story MEP penthouse roof lateral and gravity systems consist of a steel-framed core, roof mechanical penthouse, screen walls, and perimeter glazed wall enclosure. e penthouse lateral system combines a steel eccentric braced frame (EBF) and a moment frame structure. e EBF provides suffi cient lateral stiff ness while accommodating diff erential vertical displacements compatible with shear wall coupling beams. e moment frame provides a backup system and helps control residual drift. Figure 2 shows the overall 3-D Revit BIM model structural systems. e offi ce tower architectural geometry is defi ned by rounded glazed corner curtain wall panels with slightly articulated radiused north-south and east-west walls extending from Level 3 to 25 on the south and above Level 6 on the north. Levels 1 to 5 form a podium with larger fl oor areas encompassing meeting house program facilities clad typically in stone, glazing, and areas with art glass. e overall footprint is typically 109 by 210 feet in plan at the upper tower levels and 109 by 250 feet at the lower podium levels. e typical story height is 14 feet, with a story height of 12 feet 10 inches at B1, 18 feet 1 inch at Level 1, 16 feet at Level 4, and 15 feet at Level 25. e gravity system of the tower and podium superstructure fl oor plates consists of perimeter steel girders that span between W14 columns located typically at 30 feet, and W18-W21 composite beams typically spaced at 10 feet spanning between the W21 girders

Figure 2. Overall 3-D Revit BIM model structural systems. and the central core. Figure 3 shows a typical framed tower level. e composite steel framing and slab system generally consist of a 3¼-inch lightweight concrete fi ll over a 2-inch metal deck. At Level 2, Level 4 mechanical rooms, and the Roof Level, the composite steel framing system consists of a 4½-inch normal weight concrete fi ll over a 3-inch metal deck. A 2½-inch normal weight concrete fi ll over a 3-inch metal deck is used at the Level 5 roof garden. At the tower’s north and south curved walls, steel framing is cantilevered up to 18 feet to allow for column-free perimeter tenant offi ce areas. e deep foundation system consists of 24-inch-diameter auger cast-in-place displacement piles supported on pile caps that resist superstructure gravity and lateral load reactions at the base of the building. A total of 363 piles extend into primarily gravel and clay deposits to very dense gravel layers at depths of 110 to 115 feet. In upper layers, liquefactioninduced settlements up to 1½ to 2 inches are expected. At the tower core, a single 11-foot-deep mat pile cap is provided, interconnected by tapered grade beam outriggers on primary transverse column lines to perimeter pile caps in the eastwest direction, to resist lateral overturning seismic forces. Grade beams typically interconnect the pile caps and a 10 to 12-inch pile-supported suspended slab on grade. Perimeter foundation walls are also supported by a continuous grade beam that spans on perimeter piles. Level 1 framing construction consists of cast-in-place reinforced concrete with a typical 14-inch slab, beams, drop panels, and Figure 3. Typical tower level framing plan. diaphragm collector elements to transfer

Figure 4. Plan of foundation model, outrigger grade beam moment diagram, and core wall mat foundation.

lateral loads from tower core walls to perimeter foundation walls. Figure 4 illustrates foundation modeling of core wall mat and grade beam outriggers.

Site Seismicity and Ground Motions

chosen for MCER using the 2014 Next Generation Attenuation (NGA-West2) model, in conformance with ASCE 7-16 and by following a non-ductile spectral matching approach that conserves the correlation between horizontal components and results in time histories that have peaks and valleys.

The site in downtown Salt Lake City is located within the Intermountain Seismic Belt, one of the most seismically active areas in the interior western U.S, with a repeated occurrence of earthquakes greater than a moment magnitude of M7 along the Wasatch fault zone. The site is located approximately 1.18 miles from the Salt Lake City Segment of the Wasatch Fault Zone. Seismic loads were developed utilizing site-specific horizontal acceleration response spectra to design the tower – service level earthquake (SLE) at a 43-year return period and risk-targeted maximum considered earthquake (MCER) at a 2,475-year return period by the project geotechnical engineering seismic hazard consultant, Lettis Consultants International, Inc. (LCI), in coordination with site geotechnical investigations by Consolidated Engineering Laboratories (CEL). Peer-reviewed by the Structural Design Review Panel (SDRP), 11 sets of fault-normal and fault-parallel ground motion records were

Performance-Based Seismic Design

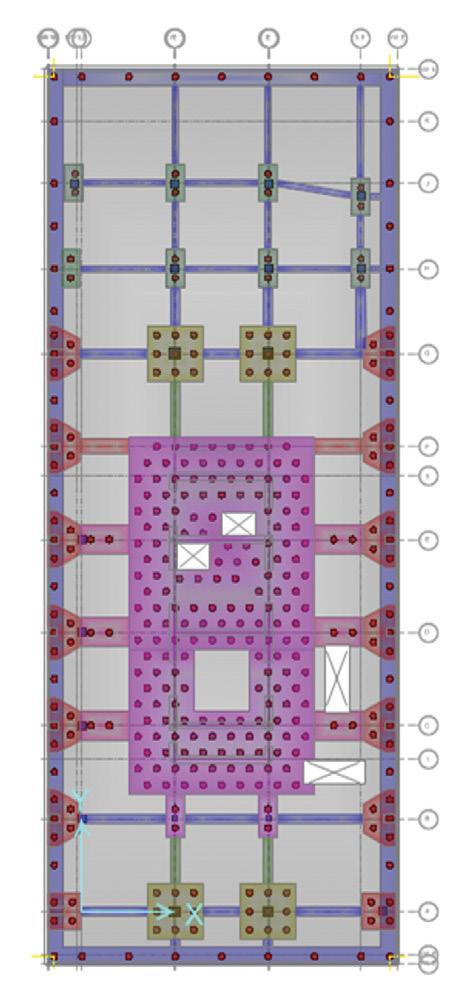

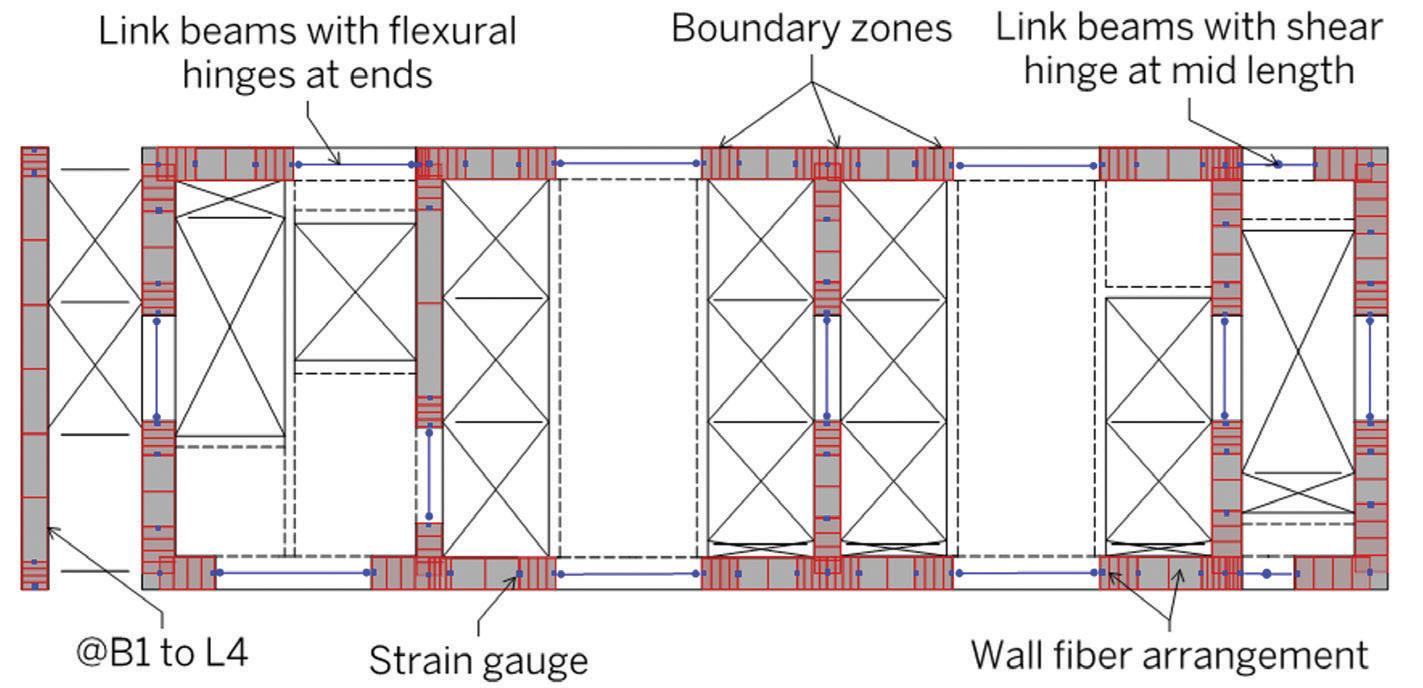

The tower seismic design is based on the PEER TBI v.2.03 (2017) performance-based guideline procedures and the SDRP review. Key unique design aspects of the project included, 1) design of an efficient and well-proportioned lateral load resisting coupled-core wall system that could dissipate seismic energy by controlled yielding of the coupling beams and hinging at the base of the building core, and 2) explicit modeling of the soil-structure interaction to capture the maximum Level 1 transfer diaphragm and basement wall backstay effects, and therefore, determine the upper-bound demands on the transfer diaphragm. The core walls are modeled using nonlinear fiber elements, and the coupling beams are modeled using lumped plasticity flexural/shear hinges in Perform-3D (CSI). Figure 5 shows the core wall horizontal section highlighting the wall fiber arrangement, coupling beams, and core wall strain gauges which capture yielding of longitudinal reinforcement. The coupling beams are modeled according to recommendations in Naish (2010), Galano and Vignoli (2000), and Lim et al. (2016). The stiffness modifiers for the component actions, where nonlinear behavior is not explicitly modeled, are used according to PEER TBI v2.03. Nonlinear analyses are performed with a suite of 11 ground motions for two separate cases to bound the backstay stresses. The upper bound lateral load in the Level 1 transfer diaphragm and perimeter basement walls are modeled using the higher stiffness modifiers per ATC 72-1, Table A-3. The foundation flexibility is Figure 5. Modeling of reinforced concrete core wall nonlinear components (Perform-3D, CSI). accounted for by using soil springs to model

Figure 6. Illustration of compliance to design criteria: a) Inter-story drift ratio; b) Fiber strain in the RC core wall.

the vertical pile stiffness. The upper bound lateral load remaining in the shear wall core is captured using relatively lower stiffness property modifiers per ATC 72-1, Table A-3. All the elements are modeled as pinned at the top of the pile cap. The structural performance is primarily evaluated by studying the inter-story drift ratios, coupling beam rotations, strain in the core wall fibers, and rotations at the end of the gravity beams in conformance with limits imposed in the detailed structural design criteria. Figure 6 illustrates compliance to design criteria with respect to interstory drift ratios and strain in core wall fibers. The MCER mean base shear force for the maximum backstay case is 15,250-kips (0.145g) in both the transverse and longitudinal directions. NLRHA ground motion analyses were typically completed in 3 to 4 days run-time. With the modeling of piles, run-times extended up to 40 days. Figure 7 shows the in-progress construction of reinforced concrete core walls and steel framing up to Level 6. The new 95 State office tower and mixed-use facility is a bold and iconic addition to Salt Lake City’s downtown urban and livable city center. The performance-based seismic design approach achieves enhanced performance, reductions in embodied carbon impact, and a LEED Gold rating.■

The authors thank the client group at City Creek Reserve, Inc., for their support in achieving project goals, and the entire design and construction team for their contributions.

The online article contains information regarding the whole-building life-cycle assessment that was performed along with an additional graphic.

Project Team

Owner/Developer: City Creek Reserve, Inc.,

Salt Lake City, UT Structural Engineer and Architect: Skidmore, Owings &

Merrill, San Francisco, CA General Contractor/Concrete: Okland Construction

Company, Salt Lake City, UT Prime Steel Contractor: SME Steel Contractors,

West Jordan, UT Concrete Reinforcement Detailer: Harris Rebar Inc,

Salt Lake City, UT

Figure 7. Construction of core walls and steel at Level 6.

Mark Sarkisian is Partner (mark.sarkisian@som.com), Peter Lee is Senior Associate Director (peter.lee@som.com), Rupa Garai is Associate Director (rupa.garai@som. com), Jiejing Zhou is Professional Engineer (jiejing.zhou@som.com), and Alex Zha is Design Engineer (alex.zha@som.com) with the San Francisco office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). Jaskanwal Chhabra is a former Design Engineer with SOM (chhabrajaskanwal@gmail.com).

Demos at www.struware.com

Wind, Seismic, Snow, Rain, etc. Struware’s Code Search program calculates these and other loadings for all codes based on the IBC or ASCE7 in just minutes (see online video). Also calculates wind loads on rooftop equipment, signs, walls, chimneys, trussed towers, tanks and more. ($295.00). CMU or Tilt-up Concrete Walls Analyze solid walls for out of plane loading and panel legs next to or between openings by automatically calculating loads to the wall leg from vertical and horizontal loads at the opening. ($75.00 ea) Floor Vibration Program to analyze floors with steel beams and/or steel joist. Compare up to 4 systems side by side ($75.00). Concrete beam/slab Program to provide bending, shear and/or torsional reinforcing. Quick and easy to use ($45.00).