4 minute read

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

USATODAYSPECIALEDITION

CLOSE TO HOME

Advertisement

Climate-Friendly Construction

Environmental activist builds sustainable house from scratch

Story and photography by Melody Burri

WHEN NEW YORK’S BLUSTERING winter winds or sizzling summer heat strike, Kathleen Draper will be unbothered.

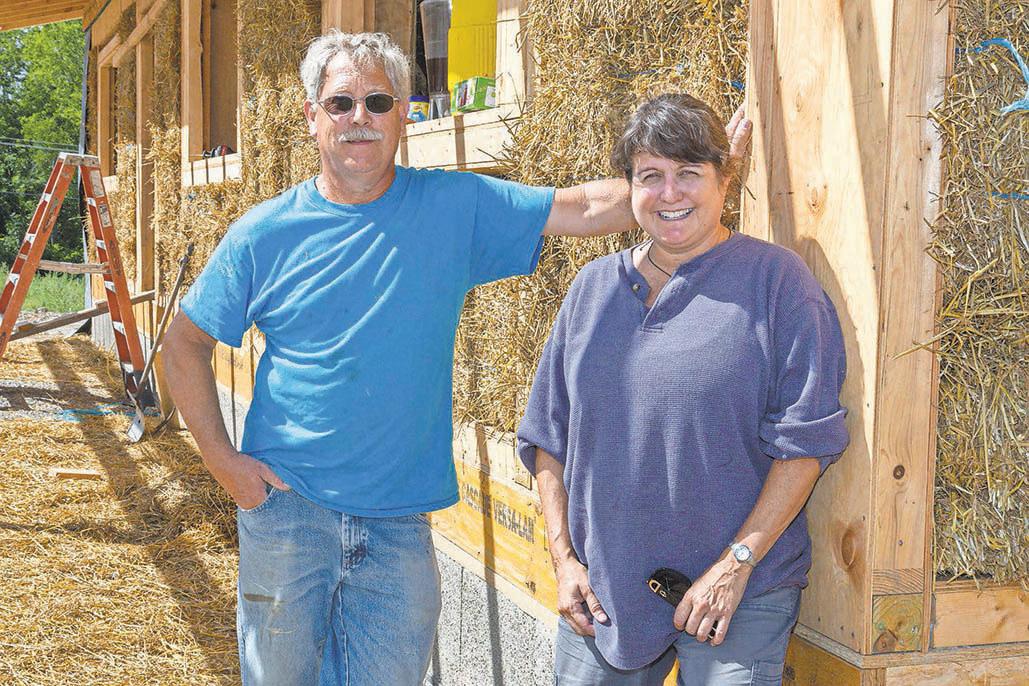

The Gorham, N.Y.-based climate change activist has constructed a 1,500-squarefoot low-embodied carbon home out of nontraditional materials such as straw bales and other carbon-sequestering materials that she says will help reduce global warming and keep her comfortable inside, despite the weather outdoors.

“I call it my ‘dwelling on drawdown’ project,” she says, referring to the future point at which the atmosphere’s greenhouse gas levels stop climbing and start declining, halting climate change.

Draper is U.S. director for the Ithaka Institute for Carbon Intelligence, a nonprofit focused on the use of biochar, a charcoallike substance that results from burning organic material from agricultural and forestry waste. She is incorporating biochar into her home’s construction.

The more than 200 straw bales Draper used were the waste product of 2 to 3 acres of wheat harvested locally. And much of the structure’s white oak, cherry, ash and hemlock lumber was cut nearby.

Why did Draper decide to build a

CONTINUED Kathleen Draper, shown here with volunteer Dave Vail, is using more than 200 straw bales to build her low-embodied carbon home in Gorham, N.Y.

USATODAYSPECIALEDITION

USATODAYSPECIALEDITION

CLOSE TO HOME

Last fall, volunteers installed straw in the eastern wall of Draper’s home. Loose straw will be milled and mixed with plaster to cover walls. A view of the great room, right, shows construction progress.

— KATHLEEN DRAPER, climate change activist

Truth window

home made with straw? Last year, New York state passed some of the strongest climate change legislation in the country, she says.

“And if we’re serious about obtaining those targets, we have to change the way we build houses and the way we use energy,” she says. “This is my attempt to minimize the amount of energy needed to keep a house heated and cooled.”

The home will use no fossil fuels but instead will be heated and powered by electricity, she says. Eventually, Draper plans to create her own renewable electricity. An air source heat pump will eliminate the need for fossil fuel.

“I think it can be done cost effectively,” she says. “So it’s smart on many different levels — economically, environmentally, and it’s very nontoxic.”

Many people have adverse reactions to toxins inside traditional homes, as well as to their poor ventilation, Draper says.

“This house has hardly any toxins — we couldn’t do it 100 percent, but to the extent possible, we minimized that,” she says.

The plaster breathes so mold issues are less likely than with dry wood, Draper says. And the paints are free of volatile organic compounds. South-facing clerestory windows on a split roof will limit sunlight in the heat of summer and welcome it in the cold of winter.

What if guests have wheat and straw allergies? No problem. Draper says they will be able to breathe freely, because the house will be fully plastered and sealed. And even the traditional “truth window” included in most straw bale structures to prove they were built with straw will have glass or plastic over it.

The cement blocks used in the basement contain half the concrete as regular cinder blocks and are prefilled with fiberglass insulation.

Does a straw bale house present a greater fire risk than traditional stickbuilt homes? Draper says no.

“Believe it or not, straw bale houses are some of the few that survived some of the California fires,” she says. “Because they are so tightly packed, it’s very hard for a fire to start. It will have an inch and a half of plaster on each side. So it’s hard to get fire in it. And once it’s in it, there’s not a lot of air to help combustion.”

Draper hosted a workshop last fall for about a dozen local and out-of-state participants, many of whom hope to build straw bale abodes of their own. The two-day event allowed volunteers to hone their skills on Draper’s home while taking a bite out of a sizable project.

Draper estimates her new home could ultimately cost upward of $250,000, including architect fees.

Draper had hoped to be in her new home in time to celebrate Thanksgiving or Christmas in 2020, but the project faced seasonal and pandemic-related delays. As eager as Draper is to move in, expected in late spring, she’s even more excited to see her first electric bill.

“My passive house guy has 2,400 square feet, and his average heating and electrical bill is $80 a month,” she says.

She would like her homebuilding project to be a positive example for others.

“Half of this effort is about showing people what’s possible, and helping local economies and doing the right thing by the climate. I really hope it will stand as something that will inspire people to do something similar or even better.”

Melody Burri writes for the (Canandaigua, N.Y.) Daily Messenger.

USATODAYSPECIALEDITION

ADVERTISEMENT