11 minute read

Bursting with Nature

The rhythm of plants

In summer, Christine Lageder always takes a final walk around her garden at around 9:30 at night. Her evening primroses only open their petals when darkness falls, so this is the perfect time to pick them. “They just make everything light up,” says the trained herbal expert. Of the 350 different plant species in her gardens, evening primroses and mallows are her favourites. The flowers and leaves from these two tall-growing plants are perfect for the tea and spice blends that she creates at her farm, Oberpalwitterhof, on the edge of the village of Barbian/Barbiano. They’re also important ingredients in her skincare and personal care products. From roses, marigolds and edelweiss to thyme, lily of the valley and comfrey, Christine grows all the main ingredients for her products on her farm up in the mountains at 900 metres above sea level. Once harvested, the plants are sent to carefully chosen manufacturers that turn them into creams, ointments and soap.

Advertisement

In her former life, Christine worked as a nurse, but in 2006 she began growing organic herbs and started her business with just a handful of products. “The stony, nutrient-poor, sun-drenched soil here is ideal.” Her four gardens, spread across her farm’s steep slopes, cover an area of 3,500 square metres. She does all of the work by hand, letting nature dictate the schedule. She begins sowing seeds in February and then gets started with her postwinter tidy-up, cutting back growth from the previous year and clearing space for the new seedlings. “I’m then in the garden every day from April to late summer,” she says. Every herb, spice and young plant has its own biorhythm, which determines whether it shoots and blooms earlier or later in the year. This means that Christine is constantly planting out seedlings, weeding, picking and drying the fruits of her labours.

In summer, her daughter and two staff members help her out. Their working day starts at 5:30 in the morning. “We have to pick the mulleins before sunrise because they wilt extremely quickly in the sunshine.” The roses also need to be harvested before it gets too hot, whereas the marigolds and chamomiles are only ready to be picked during the hottest part of the day. Christine has taken many training courses and is now a real expert in plants, their natural properties and how best to harness them. In creams, evening primrose oil has a nourishing effect, while mallow calms the skin. Marigold has healing properties and protects the hands and lips, while edelweiss provides natural protection against the sun and supports the skin’s elasticity. Christine is also passionate about providing guided tours through her gardens so she can share her expertise with guests.

Harvest season is over by late September. The arrival of autumn is then the perfect opportunity to get everything shipshape again and to clean up the storeroom and the drying and preparation room. Autumn is also the time when Christine mixes her packs of dried flowers and herbs and gets all her products ready to be sold on her online shop, at her farm shop and at markets. “Christmas is the most stressful period,” she says. But once the festive season is over, she can finally take a leaf out of nature’s playbook and rest and recharge – before the new gardening season starts up again in February.

oberpalwitterhof.com

Too precious to throw away

When the Untereggerhof farm in Vals/Valles near Mühlbach/ Rio di Pusteria switched from keeping cows to keeping goats in 2008, it set itself the goal of not wasting a thing. But that turned out to be easier said than done. Every year, the farm’s 140 German White Noble goats produce 100,000 litres of milk, which Richard Zingerle and his son Manuel, a trained dairy specialist, use to make cheese. Every 10 litres of goat’s milk yields a kilogram of cheese, but the process also creates whey – 90,000 litres of it every year, in fact. “There’s a lot of waste in cheesemaking,” says Manuel, who took over the farm from his father in February 2023, having already given up his career as a carpenter when his father started focussing on goat rearing.

Manuel spent a long time trying to find a use for the whey instead of simply throwing it away like most people do. Packed full of important minerals, lactic acid bacteria, vitamins, fatty acids and proteins, this watery, yellowy-green by-product of cheesemaking is far too precious to discard. After dismissing idea after idea, Manuel was finally inspired to offer his fresh whey to local spa hotels after an older lady with sensitive skin told him that she only ever bathed in whey. Unfortunately, the hotels weren’t interested, and he couldn’t shift a single litre. Unfazed, he continued his search and eventually found a producer that could turn the whey into skincare and personal care products. The first products were launched in summer 2018 and included a face cream, body lotion, hand cream, shower gel and shampoo. All the products have a delicate vanilla scent and Manuel and his parents, both of whom still work on the farm today, also use them themselves. They are sold directly from the farm, online, by specialist retailers and through a wholesaler in Germany that supplies beauty salons.

Instead of water, each of Untereggerhof’s seven skincare and personal care products contains at least 60 per cent goat’s milk whey. “Goat’s milk whey is highly moisturising and can restore the skin’s natural balance,” says Manuel. The only problem is that the lactic acid bacteria in the whey make it easily perishable, so it has to be frozen or transported to production facilities for processing extremely quickly. Manuel firmly believes that products with a long shelf life such as his are a fantastic way of using as much whey as possible. However, he is fully aware that it would be impossible to find a use for all 90,000 litres of whey his farm produces every year. Nevertheless and despite the huge amount of time they spend marketing their products, the Zingerles are proud of what they’ve achieved.

unteregger.it

Distilling the mountains

To the untrained eye, it’s impossible to tell how much work goes into the little dark brown bottles of oil produced by Meinrad Rabensteiner’s historic pine oil distillery on the Barbianer Alm mountain pasture. The oil itself is distilled from branches and needles collected from the trees around Barbian/Barbiano in a process that takes six to eight hours. Before that, the small branches have to be harvested, dried for several weeks, cut up and placed in the metal vat ready for distillation. Meinrad’s great uncle first began distilling essential oil from mountain pines at this distillery, 1,850 metres above sea level, in 1912. The family passed on their knowledge of steam distillation from generation to generation, and today Meinrad keeps the tradition going.

In 2016, he gave up his career as a carpenter to dedicate himself to running the distillery. He has also since joined forces with a laboratory that turns his natural essential oils into personal care products. Swiss stone pine lends his shampoos, soaps and deodorants a spicy, woody scent, while the highly fragrant mountain pine is perfect for soothing balms for aching muscles or combining with resin-scented spruce in chest rubs. Meinrad’s essential oils are also wonderfully effective in their pure form. They are calming, help relieve the airways, loosen up coughs and have antiinflammatory properties, making them the ideal remedy for many complaints. You can inhale them to ease colds, rub them into the skin to relieve joint pain and muscle aches or use them in oil burners and as sauna infusions to create a relaxing ambience.

Meinrad distils mountain pines, Swiss stone pines, spruces, Scots pines and junipers. As a rule of thumb, the longer the needles, the more oil you can extract from them. The oil is distilled using steam at a constant temperature of 90 to 95 degrees Celsius. Meinrad keeps a close eye on the temperature and continuously stokes the furnace under the boiler to keep it hot. The steam from the boiler then rises up through pipes until it reaches the metal vat containing the choppedup branches and their needles, causing the oils and aromas to be extracted. The vat can hold around 1.6 cubic metres of wood, which is enough to produce three-quarters of a litre of mountain pine oil. With Swiss stone pine branches, the yield is slightly higher. In total, the distillery produces between 70 and 100 litres of oil a year.

“My ancestors used to distil huge quantities of mountain pine oil for delivery to wholesalers,” says Meinrad. Back then, there was enough work for the entire family and up to a dozen employees. Today, Meinrad sells his certifiedorganic products under the label “Original Barbianer” directly from the distillery, online, through selected retailers and markets, and in several hotels. The 41-year-old does most of the work in the forest and at the distillery on his own, while his partner, Andrea Unterkalmsteiner, takes care of the paperwork and gives guided tours. Ten years ago, there was talk of modernising the over 100-year-old distillery and all its machinery, but eventually the decision was made to leave it as it was. It is a piece of family history, after all. The only part to have ever been replaced was the old furnace in 2021. “It had finally succumbed to old age,” says Meinrad. And that’s hardly surprising after 109 years of excellent service! latschenkiefer.it

Busy bees

Each year, Erich Larcher’s bees have a short yet intense working season, the success of which is predominantly determined by the weather. “In ideal weather conditions, a bee colony can produce up to 30 kilograms of honey in a short space of time,” explains the beekeeper. Besides sweet, golden honey, the other fruits of bees’ labours include beeswax and propolis. All three products boast moisturising effects, provide relief to rough, irritated skin, and have wound-healing and antibacterial properties. And it was precisely these qualities that inspired Erich, back in 2014, to start turning them into skincare and personal care products. He began by making eight products for the face, body, hair, hands, lips and teeth, but has gradually expanded his range to more than double that number.

Over the years, the number of bees he owns has also grown. When he entered the world of beekeeping as a 14-year-old back in 1988, he had just two colonies of these hard-working little creatures, but today that figure stands at around 180. Each colony has its own queen and thousands of worker bees. “Between ten and twelve thousand, in fact,” says Erich. In summer, the number of bees can soar to as many as 50,000 per colony once the queen’s eggs have hatched. If the weather is warm enough, the bees’ work begins in late April when they head out into the meadows in search of nectar from the flowers already in bloom. Once the trees begin to blossom, the bees spread out into the woods too. By mid-July, the flower and forest honey is ready for Erich to collect from the beehives. It’s then time to prepare the bees for the next year by “feeding them up with liquid wheat starch to give them enough sustenance to get them through the winter”. After all, the honey would normally be the bees’ natural source of nourishment for the colder months, which is why they store it in their hives and seal it with beeswax.

To extract the liquid honey from the honeycomb, Erich first removes the golden-yellow layer of wax covering the small hexagonal holes. In his words, this beeswax is “a pure and natural raw material that is ideal for personal care products”. As well as preserving the wax, he also extracts any propolis – a sticky substance that bees use to seal cracks in their honeycomb – from inside the intricate structures in the hive. After deep-freezing the propolis, Erich can shave off pieces and grind it up, ready to be used as an ingredient either in powder form or dissolved in alcohol.

Erich’s range of honey-based personal care products are produced in a lab. The individual products are then packaged at his business premises in his home town of Vahrn/Varna near Brixen/Bressanone. As soon as they are opened, the boxes, tubes and pots give off an unmistakeable sweet, floral honey aroma, which is enriched by wonderful resinous notes in the products containing propolis and is even more intense in those containing beeswax. All Erich’s products bear his name and he sells them at markets, in an online shop and through select retailers. “I’d love to see more of my products in hotels in the future,” says Erich, who has been the Chairman of the South Tyrolean Beekeepers’ Association since 2021. He also uses his 35 years of experience and the knowledge he has gained through numerous training courses in Italy and abroad to teach courses for other beekeeping enthusiasts. After all, in his words, anyone who works with bees must never stand still.

larcher-honigprodukte.it

The beekeeper extracts propolis from inside the intricate structures in the hive. It is used as an ingredient either in powder form or dissolved in alcohol.

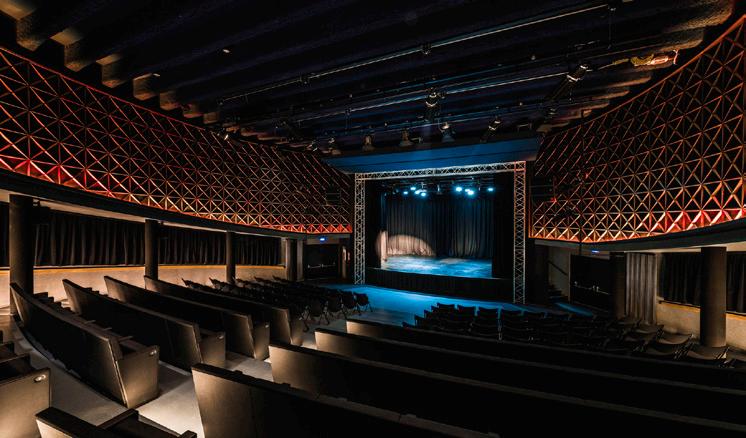

Built in the 1930s as a fascist educational centre, the Astra in Brixen/Bressanone enjoyed a second life as a cinema for over 60 years. Today, it has been transformed into a cultural venue where young artists and performers unleash their creativity

Italy’s fascist past

The Astra building was constructed on Romstraße/Via Roma on the edge of Brixen’s old town in 1936 on behalf of the fascist youth organisation ONB (Opera Nazionale Balilla). Originally called Casa Balilla, it later became known as the GIL after the Italian fascist youth movement Gioventù Italiana del Littorio and was used to instil the ideas of the fascist regime in children and young people aged 6 to 21. Here, boys and girls took part in theatrical performances and gymnastics, as well as marches on the parade ground outside. The aim of all these activities was to indoctrinate the young people with “virtues” such as national pride, obedience and loyalty to authority.

Retro chic

Today, the “Astra” lettering above the building’s entrance lights up at night and is visible from far and wide. The typography remains exactly the same as the original 1960s neon sign.

One of five

In addition to the Casa Balilla in Brixen, the two architects Francesco Mansutti and Gino Miozzo from Padua also built four other building complexes in the 1930s in Bolzano/ Bozen, Meran/Merano, Sterzing/Vipiteno and Bruneck/Brunico. All five had very similar architecture and all were built for the same specific purpose of increasing young people’s loyalty to the fascist regime. Besides the Astra, the only other complex still standing is the building in Bolzano, which today houses the Eurac Research Centre.

Pompeian red

The Astra building originally had a red plaster façade. This was later painted an ochre yellow, but during the recent restoration work, the building was restored to a striking Pompeian red, a colour inspired by the frescoes of the ancient, ruined city of Pompeii at the foot of Mount Vesuvius.

Italian functionalism

In direct contrast to the monumental fascist architecture seen in the Piazza Vittoria (“Victory Square”) and Corso Libertà (“Freedom Avenue”) in Bolzano, the Astra building in Brixen showcases the functional style of Italian razionalismo or rationalism – an architectural trend known for creating buildings with a simplistic, modern design.

Cinema

When the fascist regime came to an end, local Gino Bernardi leased part of the building, turned it into a cinema auditorium and gave it the name that lives on to this day: the Astra. He later passed the baton to his son, who continued to manage the cinema until its closure in 2011. For 65 wonderful years, the Astra cinema was an integral part of Brixen’s culture scene – and it always kept up with the times. When the soft porn industry was booming in the 1970s, for example, the Astra didn’t shy away from showing many a raunchy film. Today, the venue continues to play arthouse and children’s films in its newly renovated grand auditorium.

Meeting point for youth culture

The Astra was reopened in 2019 following extensive renovation work. Local architecture studios redesigned the building for the modern day, creating a 670-square-metre venue and cultural hub, where young artists and performers can unleash their creativity. Inside are workshops for artists and also a grand auditorium, which plays host to a diverse programme of concerts, talks and performances.

Gerhard Kerschbaumer was one of the world’s best cross-country mountain bikers. Now the cycling pro has left the racing scene behind to fulfil his dream of becoming a farmer. We chat to him about daring descents, rearing cattle as nature intended, and the common ground between sport and farming

Gerhard Kerschbaumer was one of the best cross-country mountain bikers in the world. He wrestled with his decision to give up his cycling career for a long while. Now he spends most of his time working in his barn – and has a true passion for farming.