SUFFOLK NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY

David Walker

Ancient House

Lower Street, Stutton

Suffolk IP9 2QE

Quercus121@aol.com

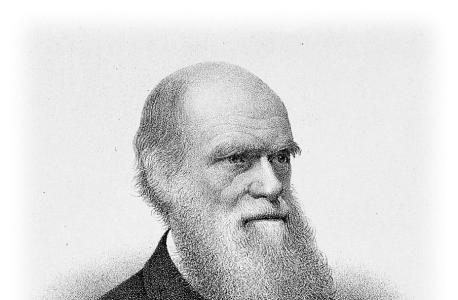

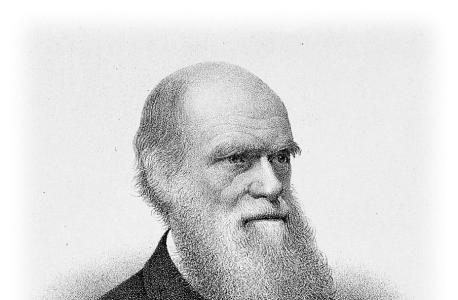

Rasik Bhadresa’s excellent essay “Let Us Celebrate Darwin”, p.2, has left me wondering what else to say about the great man in his bicentenary year, so I’ll just let the stream of consciousness flow, and hope that it’s not a string of entirely unconnected thoughts.

Darwin saw the storm stirred up by “The Origin”, but did he imagine it still going on after 150 years? The inane intelligent design argument immediately springs to mind but more fascinating is the discovery that the cow genome contains a piece of snake DNA that it picked up about 50 million years ago. This is one example from the growing body of evidence that ‘the tree of life’ concept may be wrong and that the phenomenon of ‘Horizontal Gene Transmission’ (HGT) is responsible for genetic traits jumping across chasms of taxonomic distance, an event not confined to bacteria as once thought but acting at all levels including higher groups like vertebrates and flowering plants. This stems from research enabled by DNA studies. What a time to be a biologist! We are very fortunate to witness the diverse fruitfulness of what only a few decades ago was looked on as ‘the soft science’.

Less fortunate are the climate scientists who have to make predictions more dire with each week that passes. Carbon-trading always seemed like a ‘smart alec’ politician’s idea but now it appears that wind farms and the like won’t stop the warming getting out of control either; they cannot keep up with the year-on-year increase in coal-fired power in China and India. And I still can’t understand why governments are bailing out the car industries in this recession. As things stand the prospects for future generations of East Anglian naturalists look grim.

Darwin’s inspiration for the mechanism of evolution may have arisen during the voyage on HMS Beagle, but most of the evidence he amassed came from observations of everyday things at home and copious correspondence with plant and animal breeders. The word evolution was carefully avoided in The Origin. Darwin had realized from early on that he ‘could not avoid the belief that man must come under the same law’ [of transmutation]. So, following publication of The Origin and after a period of refuge in the uncontentious study of orchids, he embarked on the Descent of Man (1871) where his theory on the origins of man was made clear. This, he said, was ‘so that no honourable man should accuse me of concealing my views’. As if...

White Admiral No 72 1

Born on 12th February 1809, Charles Robert Darwin would have celebrated his 200th year this year. His lasting legacy continues to thrill and delight us and so it is only appropriate that we celebrate with gusto not only his ideas on evolution but also his enthusiasm for nature, his amazing powers of observation, his deep biological insights and his mental tenacity. A true naturalist!

However, even after all these years, with all the evidence that the scientific community has accumulated, Darwin’s theory of natural selection and the origin of species, firmly embedded in modern biological philosophy, continues to be misunderstood. Since the theory itself is simple, the reason can only be that some of us deliberately choose to believe in unverifiable ideas about our origins. But what is worse, people also resort to ‘throwing stones’ to make their own positions more tenable. It was exactly for these reasons, from fear of similar reactions, that Darwin took so long to publish his great masterpiece, The Origin of Species in 1859, nearly twenty years after the theory had formalised in his own mind. In the context of 19th century Victorian England, this fear could well be understood. But in this present day and age, when we know so much more about inheritance, when the human genome itself has been fully mapped, isn’t it quite incredible that Darwin may not be taken seriously? Isn’t the search for truth man’s worthiest endeavour? What has to be readily realised and acknowledged is that the scholarly Darwin, like a good scientist, endeavoured simply to draw conclusions and furnish explanations for his expansive understanding and study of living things, past and present.

The central arguments of his theory are quite straightforward - a couple of facts that cannot be denied and a conclusion any thinking person could not truly refute:

1 All living things vary, and these variations are passed on to their offspring.

2 Living things produce more offspring than can possibly survive.

3 Offspring that vary more strongly in ways favoured by the environment will survive and reproduce. This variation that favours the species will therefore accumulate in populations. This is what Darwin calls Natural Selection.

White Admiral No 72 2

LET US CELEBRATE DARWIN

A good example of natural selection is the increase of the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) often described as a ‘superbug’ in the media. What has happened is that when exposed to antibiotics those individuals that possessed mutations which made them slightly impervious, have survived. And over many generations, the selective endurance of well-adapted individuals has given rise to ‘super’ resistant bacteria.

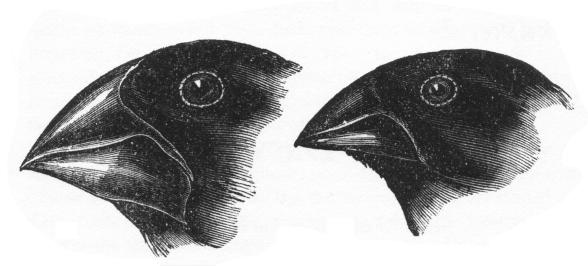

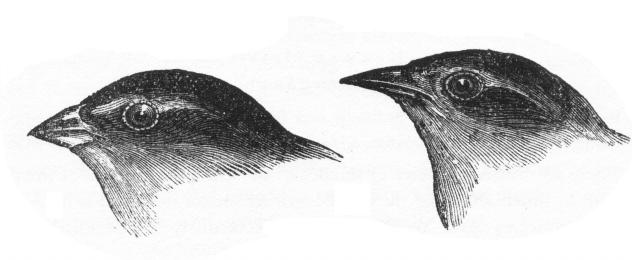

The importance of Darwin’s theory is in his belief that natural selection is the creative force of evolution, that is, it creates the fit, not just eradicates the unfit. Therefore for natural selection to be creative, the variation has to be random. Selection could not play a creative role if variation came pre-packaged. Thus natural selection builds adaptation stage by stage by conserving, over many generations, the most favoured part of random variation. Modern understanding of genetics and genetic mutation clearly indicates that Darwin was right about this. Evolution is thus a blend of unexpected happenings at the point of variation and what is necessary in the operation of selection. Apart from being random, variation must also be diminutive in relation to the degree of evolutionary change requisite in the formation of a new species. Again modern day genetics supports the view that minute mutations are the embodiment of evolutionary change. Thus Darwin’s theory is not without its delicate intricacies.

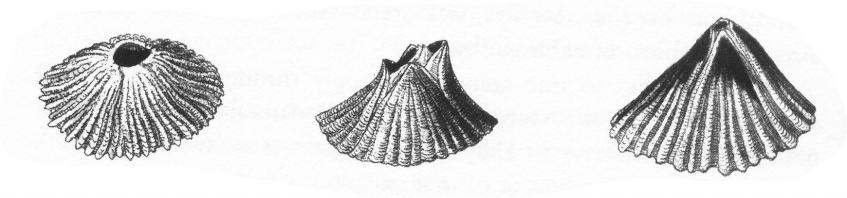

However, it is probably not the theory itself that stops it from being accepted, but rather its radical philosophical message - that evolution has no purpose or direction and that ‘matter’ is the root of all existence, of body and of mind. Darwin was not prepared to assign to nature mankind’s deeply held conceited view that we, human beings, were the masters of the earth and all living things because we were the superior product of a preordained process. Modern palaeontologists tell us that evolution of living things that blossomed out in much profusion has occupied a period of around two billion years. If we or ientate ourselves to this time scale, then we find that mammals appeared 150 million years ago and the footprints left by man and his Homo predecessors encompass two million years! And the origin of life itself predates the origin of species by at least another billion years. This too was an extremely gradual process during which a long stepwise chemical evolution took place as a necessary preamble to the emergence of Life. The body of evidence is simply too great to be discarded and in any event we must come to terms with not only Darwin and his revolutionary view of life but also the palaeontologists, the ecologists, the geneticists and the organic chemists.

More than anything, what Darwin has done is to free us to enjoy delving

White Admiral No 72 3

deeply into our origins and allowed us to construct a new demonstrable biological reality. Further, Darwinism actually created a ‘gap’ that we had to fill – to find and define man’s own purpose on this beautiful planet of ours. Although it freed and released us from the pressure of having to believe, it did not, by the same token, prohibit human beings from believing in God, especially when this belief centred on a deep love of life and all living things. Since each individual has the freedom to define ‘man’s own purpose’, Darwinism cannot and does not forbid a belief in God. Darwin, himself preferred to describe himself as ‘an agnostic’! Natural selection does not preclude us from enjoying life, but better still it

gives a deeper meaning to our interactions with nature. Herein lie the seeds of conservation. As responsible Homo sapiens we have to take care of our wonderful earth. The world has changed a lot since Darwin’s time, but it is definitely not any the less exhilarating, enlightening or inspirational. So even if there may not be an ultimate purpose in nature, we can be glad that we are free to define it ourselves. For this freedom and not forgetting the gift of his supreme insight into our view of life, I would like to raise a glass to dear Darwin! Long may the grandness of his view flourish.

Rasik Bhadresa

SUFFOLK NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY

ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

7.00pm, Wednesday 22nd April 2009

Holiday Inn, Ipswich

To be followed by a presentation by Dr Simone Bullion, author of the soon to be published “The Mammals of Suffolk”

Refreshments provided

White Admiral No 72 4

Systema Naturae

The green beetle grades the grass-blade Millimetre by millimetre, Guides the gaze

Upwards and out

To the tree.

To species

Through synonym

Through genotype

To genus.

To family

To superfamily

To order.

To class

To phylum

To kingdom.

To life.

Dizzied, The eye descends

To the powdered, granulated, emerald weevil, Its antennae waving,

Its elytra bright.

All learning is little

And therefore dangerous.

There is so much to be grasped.

Alasdair Aston

White Admiral No 72 5

GETTING CLOSER TO NATURE

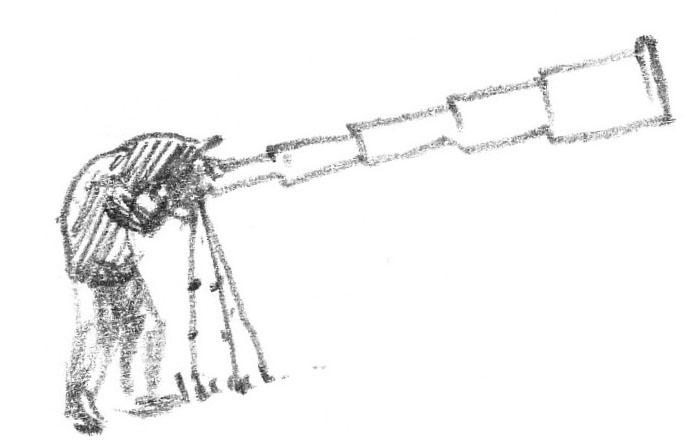

A pair of barn owls set up home in a very old, gnarled oak tree on a private estate adjacent to Alton Water. I wanted to photograph the owls but I could not get nearer than 100 metres from the tree along a public footpath: too far away for even the most powerful camera lens to produce a reasonable picture. I thought about digiscoping, that is using a telescope to magnify the image and then attach a camera to the telescope to take the picture. This is a relatively new idea which came about with the advent of the digital camera, which is much smaller, lighter and are capable of taking hundreds of photographs at a time. At first the camera was held to the eyepiece of the telescope but now special adaptors and compatible kits are available. As expected, using a telescope brings the subject very close from very long distances, a quarter of a mile or more. Until now digiscoping has not had a very good press as I was to learn when I visited my local shop to buy some equipment.

Having been shown some very indifferent photographs I was somewhat surprised and deflated by the answers to my queries. I recall the shopkeeper:

“You are the same as the rest of ‘em who come in ‘ere. You think you can buy cheap digiscoping equipment and get the same results as the professionals who sit in hides all day with long lenses.”

But my subjects were too far away for even the most powerful camera lenses (excluding TV camera lenses) and sitting in a hide all day would not help. Thus encouraged I decided to go ahead and purchase my equipment but from a different shop. Recommended equipment consists of a good quality telescope (Nikon call their telescopes, fieldscopes) preferably with a wide objective lens (where the light enters the telescope) and either a 20x or 30x eyepiece.

The camera should be of the Compact variety, have about 10 million pixels, a zoom lens and, most importantly, a cable release.

An adaptor is required to fasten the camera to the telescope eyepiece. Several universal models are available.

Fortunately Nikon sell a completely compatible kit, which I purchased. It consisted of:

A Nikon ED82 Fieldscope with a 30x eyepiece. This comes in a straight or bent version (you look down through the latter). Either will work with a Compact camera.

The camera, a Nikon Coolpix P5000 with 10 million pixels (this has now been updated to P5100 with 12.5 million pixels) and a 3.5 x optical zoom with conventional (35mm equivalent) focal lengths between 36 and 126mm. Using the

White Admiral No 72 6

maximum zoom126 mm gives an effective focal length when on the telescope of 30 x 126 = 3780mm ! (30 is the magnification of the telescope eyepiece). The longest conventional focal length on a camera is about 1,000mm.The Coolpix can also take short video clips and these are quite useful if the subject is moving excessively or you want to identify a bird on a windy day. Played back on a computer the quality is quite acceptable with an image size up to 10 x 8 cm.

Finally the Digital Camera Bracket which holds the camera to the telescopecompletes the package. The Nikon bracket is supplied with a manual cable release, which is essential as camera shake at such huge magnifications is an important factor. It is a pity Nikon did not build an electronic cable release into the camera as the cable release is the second most important factor after the compatibility of the equipment.

Armed with my equipment and a substantial tripod I returned to the oak tree but the owls didn’t turn up. Instead, while I was waiting a bird flew onto the uppermost branch of the oak, so far away that it appeared to be an extension of the branch rather than a bird. I took a photograph. Once home I downloaded it into the computer. It was a kestrel. The quality was astonishingly good especially considering the distance the bird was from the camera. It would not have been possible to take the picture with a conventional camera and long lens.

Digiscoping is only suitable for subjects that are still and remain in one place. Moving subjects are out and a tripod is essential. The procedure is to set up the telescope on a firm tripod and manually focus it very carefully on the subject to be photographed. The camera is then switched on and slid carefully onto the telescope eyepiece. The camera zoom can now be used to enlarge the image. The camera focuses automatically and there is no reason to use the camera monitor to focus but it should be used to check that the subject is positioned correctly.

Viewing the image on the camera monitor can be difficult if the sun is shining onto it. The commercial shades are good at protecting the screen from scratches but not shielding it from bright sunlight. If possible it is best to move the equipment into the shade. Failing this, view the monitor from under a black cloth (going back 100 years!). I have now taken to wearing a baseball cap with the large Donald Duck peak, which I swivel round my head so that the peak of the cap shades the monitor. To look closely at the monitor I wear a pair of high magnification (+4 dioptre) reading glasses, which can be bought very cheaply from most pharmacists. Like everything else it takes time to acquire technique but the trouble is well worth while as digiscoping reaches the subjects conventional cameras cannot reach.

Russell Edwards

Photographs on p.17

White Admiral No 72 7

EPICHLOE AND THE FLY

Fifty years ago I did my PhD researching an ascomycete fungus Epichloe typhina and published some of the results in Transactions of the British Mycological Society (Kirby, 1961). Recently during a Mushroom and Toadstool walk on Westleton Common, Sheila Francis mentioned that she had seen a citation to my paper in a recent paper by Spooner & Kemp (2005). I had given up any study the fungus after the paper was published to concentrate on the physiology of flowering in the cereals and grasses and so I was intrigued to find out how my work was still relevant.

What I found was great changes in basic mycology, fungus systematics and the understanding of fungal sexuality,

I became interested in Epichloe typhina which causes choke of grasses as a schoolboy. It chokes off the grass inflorescence with a fungal stroma which in the later stages turns bright orange. Leicestershire, where I lived, was a county of long established permanent pasture and the fungus was widespread, particularly in ungrazed areas. I tried digging up infected plants and planting them in pots in the garden and found that the grass plant appeared healthy and vigorous while vegetative but the fungus reappeared in successive years when the grass flowered. This, combined with a developing interest in the effect of day-length on flowering (photoperiodism), led me to persuade the scholarship awarders that it was a suitable research topic for an aspiring young PhD student.

‘In my time’ there was one species of Epichloe, infecting a range of perennial grasses. It was not known how it spread from plant to plant and I think that I had a naïve impression that the endophyte fungus formed a stroma which produced conidia before the ascospore producing perithecia. I made no progress with plant to plant infection methods but I was able to show that in the vegetative plant the fungus was a benign endophyte with sparse hyphae growing between the cells of the plant tissue, but in the very early stages of floral initiation (long before the stem elongated and the inflorescence was visible) the fungus became rampant and formed a mass of hyphae (Photo p.18). This generally completely choked the inflorescence, although the degree to which this occurred could be affected by artificially prolonging the day-length, which speeded up flowering and allowed the inflorescence to wholly or partially escape from the fungus.

There I left Epichloe typhina and apart from noticing a paper from the Welsh Plant Station at Aberystwyth which applied my ideas to induce severely infected lines of cocksfoot to flower and produce seed, I forgot about Epichloe.

Oh, how things have changed! Epichloe has been split into six or more species, each specific to one or a few species of grass, the infection method and the sexuality have been worked out and the effect on grass growth and grazing animals has been established.

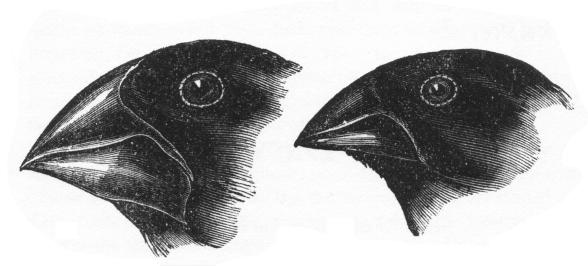

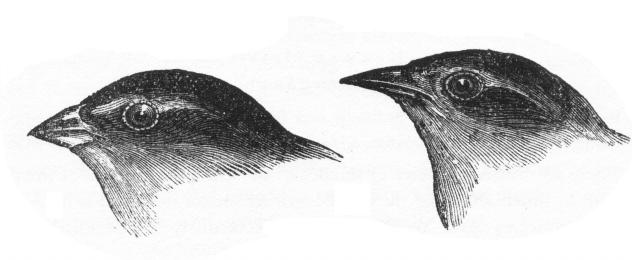

Of most interest to naturalists (and this is the main point of the story) is the relationship between the grass and the fungus, the sexuality of the fungus and a small fly. Epichloe is heterothallic and needs the union of two mating types to produce

White Admiral No 72 8

ascospores. The role of the fly, Botanophila sp. (Anthomyiidae) which lays its eggs on the fungal stroma, is to transfer spermatia (gametes), which are formed on the stroma, from one mating type to another. Feeding on the stroma it eats spermatia; later visiting another plant with a stroma of a different mating type it deposits spermatia, which pass unaffected through its gut, in its faeces where they may come into contact with the receptive hyphae of the developing perithecia of another mating type. Union of the gametes is followed by meiosis and the stroma turns bright orange and produces eight needle-shaped ascospores which are ejected and may infect other plants. The larvae of the fly feed on the fungus, concealing themselves in chambers made in the stroma.

This remarkable mutualistic association involving Epichloe, a grass plant, and a fly is another complex relationship similar to the one described by Peter Payne (White Admiral 70; 20) involving a mycorrhizal fungus, a tree and an orchid. Such associations provoke questions about how the balance between the different members is maintained. Why do not the fly larvae eat large portions of the stroma and reduce the spore output of the fungus or the parasitic orchid kill the mycorrhizal fungus? And in the Darwin centenary year we may perhaps reflect on how such complex relationships evolve. Some of the questions are within the scope of the garden naturalist. A close watch on the infected Holcus mollis plants in my garden to look at numbers of Botanophila larvae and their enemies is indicated for 2009.

References

Kirby, E. J. M. (1961). Host-parasite relations in the choke disease of grasses. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 44: 493 - 503.

Spooner, B. M. & S. L. Kemp (2005). Epichloe in Britain. Mycologist 19: 82-87.

Michael Kirby

SNIPPETS

• Too few mycologists - according to CABI (Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux International) the national research data base for mycology is in danger of collapse owing to the lack of experts .

• The swift population of the south-east fell by 55% between 1997 and 2007. A major threat to the species is destruction of nesting sites when renovating buildings. See www.swift-conservation. org for more information.

• The new Guide to Garden Wildlife by Richard Lewington is highly recommended for its excellent drawings and as an identification aid. Pbk, £12.95, published by British Wildlife Publishing.

• Contraceptive injections are being trialled to control wild boar populations in the Forest of Dean.

• Insects threatened by rising sea levels include the rare sea-aster bee and the fen mason wasp. These species will not be able to retreat to marshes inland if they are cut off by sea walls; they need managed retreat schemes.

White Admiral No 72 9

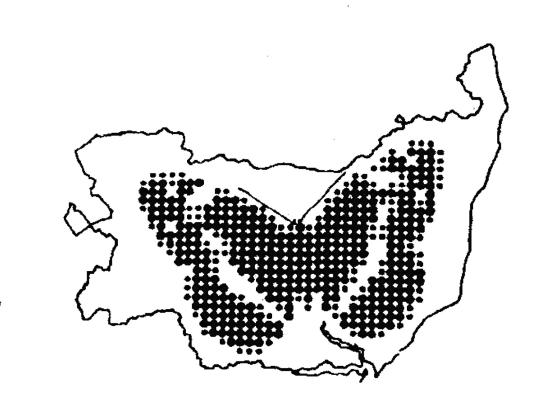

ARE THERE ANY CHORDEUMATID MILLIPEDES IN SUFFOLK?

Compared with the majority of the country the millipede fauna of Suffolk is relatively well known. However, no members of the family Chordeumatidae have been recorded from the county. Five species occupying two genera are currently known in Britain. The three British Melogona millipedes are small species, 5-10mm in length and less than 1mm in diameter. They are white to cream in colour and on closer examination display prominent ‘cheeks’ typical of the family. Above each cheek is a narrow, elongate triangular eye composed of five, six or seven vertical rows of up to four tiny black dots. The two British Chordeuma species are larger (length 10-13mm, diameter 1.2-1.5mm) and brownish in colour. They still have the prominent ‘cheeks’ but each eye forms an equilateral triangle. Although the national atlas (Lee, P. 2006. Atlas of the Millipedes (Diplopoda) of Britain and Ireland. Pensoft.) shows that all of the chordeumatids have a western bias to their distribution, the most widespread of these millipedes, Melogona scutellaris, does occur in Essex. Based on current distribution patterns, two other species, Chordeuma proximum and Melogona gallica, could conceivably occur in Suffolk also.

Chordeumatid millipedes typically have an annual life cycle. They usually occur in leaf litter in woodland habitats and are adult and active in the winter months. Collecting invertebrates in the midst of winter can be uncomfortable and this means that they are often under recorded even within the core of their range. One option the less hardy naturalist can consider is to remove the habitat to a more comfortable location; the leaf litter can be collected and then sorted through in warmer conditions, possibly on the dining room table if you can get away with it! However, it is often considered more efficient to use an extraction technique to separate small, relatively inactive invertebrates from the substrate.

Most SNS members have probably come across the Tullgren funnel in their school studies if nowhere else. Basically this consists of a funnel with a small sieve or circular piece of mesh placed in the top. The litter sample is put in the sieve / mesh and a heat source e.g. a light bulb is arranged above it. The heat dries out the litter from above forcing invertebrates to move down through the litter to find the moist conditions they prefer. Eventually they reach the bottom and end up falling through the holes of the sieve and down the funnel into a collecting pot. For the amateur, Tullgren funnel extraction is really only feasible with small volumes of material yet the process is least efficient in such circumstances as the litter is more likely to dry out too rapidly. A more practical alternative is to allow a larger volume of litter to dry naturally in a Winkler extractor. Although similar in principle to Tullgen funnel extraction, in a Winkler extractor the funnel (and sometimes the sieve) is replaced by a net. There are conflicting reports on the efficiency of these extraction methods compared with each other and other extraction techniques. However, there can be no argument that using an extraction technique is a more naturalist friendly way of recording litter invertebrates than crawling around on

White Admiral No 72 10

hands and knees in cold, damp conditions in the depths of winter.

As with most specialist equipment, Winkler nets can be expensive to buy. Therefore, with support from an SNS bursary, I set about producing a simple homemade version to enable leaf litter from Suffolk woodlands to be checked for the presence of chordeumatid millipedes. The extraction ‘funnels’ were constructed from rectangular plastic compost sieves (approx. 45x30cm) hung from the rafters of an unheated garage. Heavy gauge polythene sacks were taped below the sieves and the lowest corner of each sack was cut away. A large collecting pot containing 50% alcohol was taped into each of the resulting openings.

Once the extraction units were prepared, three woodland sites in the south of Suffolk (hence closest to the known Essex locations for Melogona scutellaris) were selected. Table 1 gives details of these sites. The woodlands were visited on 30th January 2007 and five samples of approximately one litre of leaf litter were collected from each. The litter was transported in sealed plastic bags and once at home was transferred to the Winkler funnels for the extraction of millipedes and other invertebrates. The litter remained in the sieves until the end of April 2007 but animals falling into the collecting pots were removed approximately every fortnight. Where feasible all invertebrate specimens were identified to species.

Ramsey Wood (management compartment 2)

Wolves Wood (management compartment 15)

Table 2 lists the invertebrates identified from the litter samples. As can be seen from the Table only three species of millipede were collected and none of these was the chordeumatids that were being sought. Previous work in all three woodlands has produced good lists of millipedes collected by hand searching. Clearly the majority of these millipede species were not detected by Winkler extraction and all of the species that were extracted had already been recorded by hand collecting. The low diversity of species extracted was notable in the other invertebrate groups also. This may have been due to the litter samples being collected just once, early in the year. At the end of January some invertebrates probably were to be found deeper in the soil rather than in surface layers of litter where conditions are colder and drier. It has often been noted that after a hard frost small, soil-dwelling millipedes such as

White Admiral No 72 11

Table 1. Details of site visited for collection of leaf litter

Site name Grid reference Dominant leaf litter components

TM1239 Sweet chestnut, beech, oak and birch

Bentley Old Hall Wood

TM0643 Oak, birch and sycamore

TM0543 Hazel, birch and oak

chordeumatids are readily collected from under stones on the soil surface but these tend to be adult or sub-adult animals. The immature stages are seen much less frequently and could well have overwintered deeper in the substrate. On reflection it would have been sensible to try and extract millipedes from the soil as well as the leaf litter and to collect new samples each month through to April in order to monitor any emergence of maturing millipedes at the surface.

One positive outcome of this work was that relatively large samples of the very common pygmy woodlouse Trichoniscus pusillus were collected. Taxonomists have recently split the species and recognition of the two requires dissection of the males. To make this more difficult one of the species, Trichoniscus pusillus s.s., is parthenogenetic and hence any population is composed mainly of females. Only a very few males are produced and these contribute little to the genetics of the population. In the other species, Trichoniscus provisorius, males and females are produced in roughly equal numbers. This means that often it is not possible to be certain as to which species is present on a site if only small numbers of females are collected. All of the specimens extracted from litter from Bentley Old Hall Wood were female and so probably were Trichoniscus pusillus s.s. but it was necessary to record them as Trichoniscus pusillus agg. because without a male specimen to dissect it was not possible to be certain of the identification. There were males amongst the sample from Ramsey Wood and the presence of a population of Trichoniscus provisorius here was confirmed. However, there were many more female than male specimens in the sample indicating that a population of Trichoniscus pusillus s.s. was probably also present but again without a male these were recorded as Trichoniscus pusillus agg.

The small number of samples worked on in 2007 was not sufficient to provide a definitive answer to the question posed in the title of this piece. The exercise did provide some indications as to how the sampling might be improved to increase the probability of detecting the annual millipede fauna of woodland litter.

metal reflector

100 W bulb

soil sample

metal gauze

smooth-sided funnel collecting pot

Fig. 1 Tullgren funnel (from Green, Stout & Taylor, Biological Science Vols I & II, 2nd Ed By kind permission of Cambridge University Press)

White Admiral No 72 12

Woodlice

Trichoniscus pusillus agg.

Trichoniscus provisiorus

Trichoniscoides albidus

Philoscis muscorum

Porcellio scaber

Beetles

Notiophilus biguttatus

Asaphidion flavipes

Megasternum concinnum

Nargus velox

Geostiba circellaris

Plataraea brunnea

Stenus impressus

Philonthus decorus

Quedius lateralis

Spiders

Hahnia montana

Harvestmen

Nemastoma bimaculatum

Centipedes

Schendyla nemorensis

Geophilus truncorum

Lithobius crassipes

White Admiral No 72 13

Table 2. Taxa extracted from leaf litter samples

Bentley Old Hall Wood Ramsey Wood Wolves Wood

Species name

● ●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

Table 2 contd.

Millipedes

Nanogona polydesmoides

Polydesmus sp.

Brachydesmus superus

Molluscs

Carychium tridentatum

Discus rotundatus

Cepaea nemoralis

Trochulus hispidus

Aegopinella pura

Aegopinella nitidula

Vitrea crystallina

Acanthinula aculeata

Acknowledgements

A SNS bursary was kindly granted to support this work. Mark Nowers of the RSPB granted permission to work in the Hintlesham Woods and Mr John & Mrs Annie Owen granted permission to work in Bentley Old Hall Wood. Roger Booth of the NHM assisted with identification of the Aleocharine beetles.

Paul Lee

FIELD MEETING WITH NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY

Sunday, 5th July at 11.00 a.m. Joint field meeting with the Norfolk & Norwich Naturalists’ Society at the Ted Ellis Trust Wheatfen Reserve, Surlingham, east of Norwich led by David Nobbs, Reserve Warden. Meet in the Reserve car park at TG 325057. Numbers of participants limited, so please phone Stephen Martin of the N&NNS on 01603 810327 to reserve a place. A small donation to the TET on the day from individuals present will be appreciated. Bring a packed lunch.

White Admiral No 72 14

●

● ●

● ●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

RAINFALL & TEMPERATURE DATA FOR BOXFORD, 2008

White Admiral No 72 15 Sept: Daily Rainfall in mm -5.0 5.0 15.0 25.0 14710131619222528 Oct: Daily Rainfall in mm 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0 1471013161922252831 Nov: Daily Rainfall in mm 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0 1357911131517192123252729 Dec: Daily Rainfall in mm 0.0 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 25.0 1471013161922252831

White Admiral No 72 16 Max & Min Temperatures September 2008, deg C -5.0 5.0 15.0 25.0

Max & Min Temperatures Oct 2008, deg C -10.0 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0

1357911131517192123252729

Max & Min Temperatures Nov 2008, deg C -10.0 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0

135791113151719212325272931

Max & Min Temperatures Dec 2008, deg C -10.0 0.0 10.0 20.0 30.0

1357911131517192123252729

135791113151719212325272931

White Admiral No 72 17

Plate 2: This curlew was more difficult to follow through the telescope as it moved along the shore probing for food. Russell Edwards

Plate 1: This Great Crested Grebe on its nest makes an ideal subject for digiscoping as it is in a fixed position about 150 metres from a permanent hide. This picture would not have been possible with a conventional lens. Russell Edwards

creamy white and is producing spermatia. The RH photograph shows an orange stroma with perithecia, producing ascospores.

White Admiral No 72 18

Choke of grasses (Epichloe sp.) on creeping soft grass (Holcus mollis). The LH photograph shows the fungal stroma which has trapped the grass inflorescence in the flag leaf sheath with the lamina growing out from the top. The stroma is

Plates 3 & 4

Photographs by Michael Kirby

White Admiral No 72 19

Plates 5 & 6: Hairy-footed Flower-bees Anthophora plumipes. Female above, male below

Photographs by Adrian Knowles

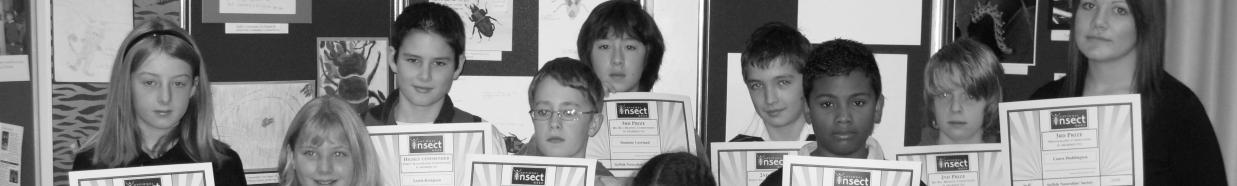

Winners of the 2008 ‘Suffolk Summer of Insects’ competition

‘From Brandon to Bungay’, Richard West’s masterly study of the landscape history and geology of the Little Ouse and Waveney Rivers has just been published and is available from SNS, c/o Ipswich Museum, High St, Ipswich, Suffolk IP1 3QH. Price £12 including p&p (£10 if you can collect from the Museum). The Society has been able to keep the price down thanks to generous support from Richard himself and the GeoSuffolk Group.

The book is A4 soft back, 106 pages of text and diagrams plus 20 pages of colour plates including eight full page aerial photos showing comprehensive views of significant features of the river valleys.

White Admiral No 72 20

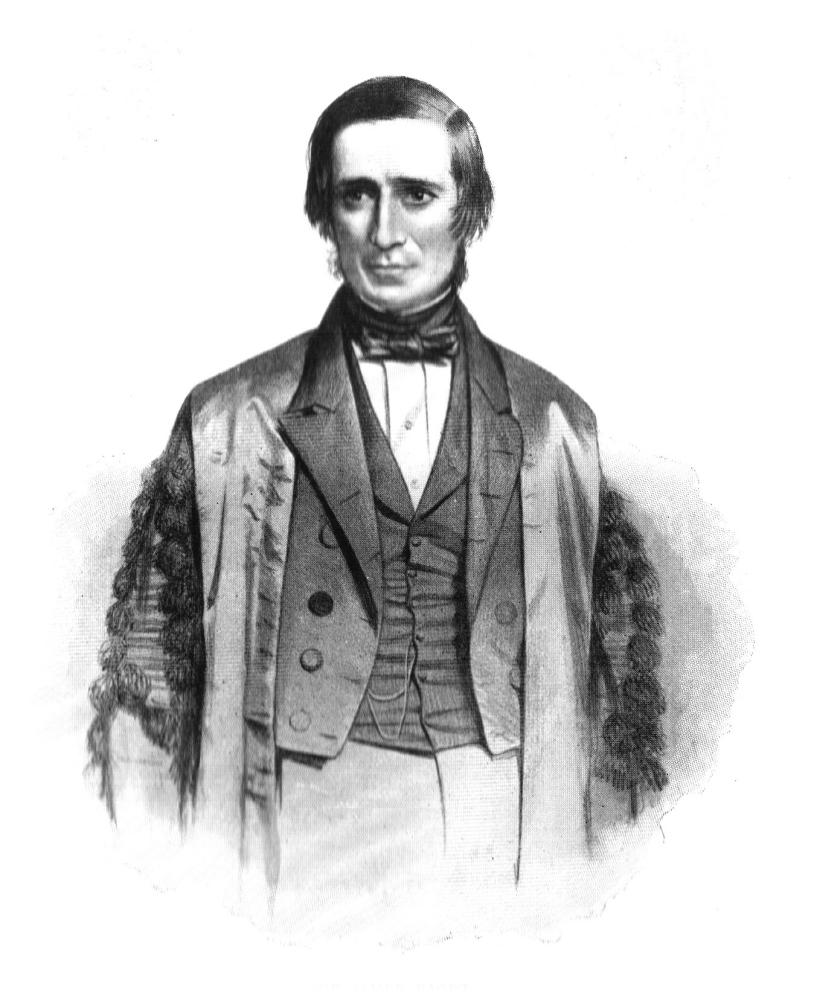

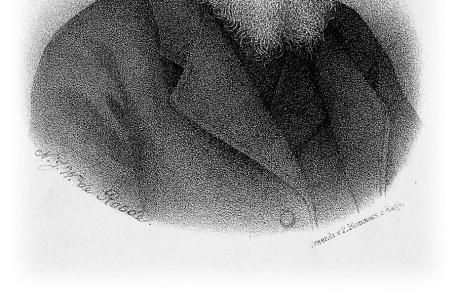

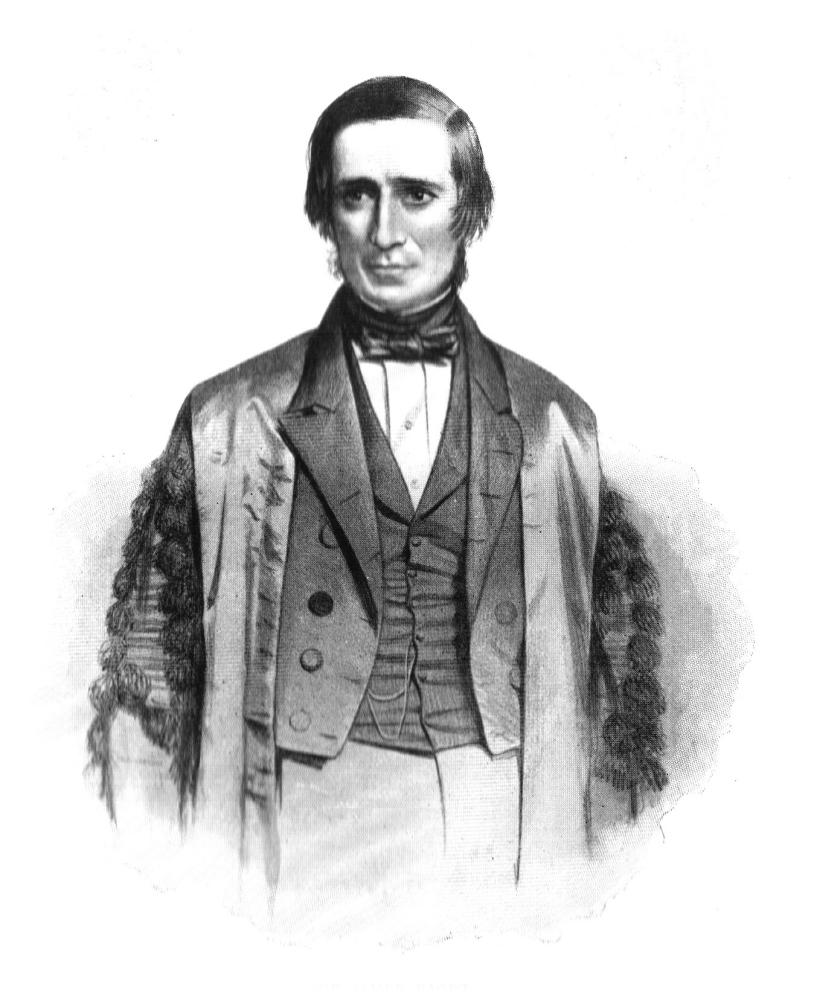

JAMES PAGET (1814 -1889) A MAN WELL-BORN AND A LIFE WELL-SPENT

Most people living in our region will be aware of the James Paget Hospital in Gorleston. Those living in that area, people of wide general knowledge and, most especially, people with a medical background or interest, or intuitive guessers will be aware that James Paget was “a medical man” whose hometown was Great Yarmouth; few, however, will be aware that he was co-author with his older brother Charles, of a book on the natural history of the areas of Suffolk and Norfolk around Yarmouth and that it contains an annotated catalogue of the animals and plants known to occur in the district. This account attempts to rectify these deficits by examining the lives of the two men in the context of their family and assesses the importance of their book from a national and local perspective. In addition, in this important Darwin anniversary year, it looks at the connections, similarities and differences between the Paget family and that of Charles Darwin.

Departure and Retrospection

At the end of September, 1834 a rather small, good-looking young man of twenty with a kind, calm-looking expression and engagingly expressive eyes, left his house on the South Quay at Yarmouth in Norfolk and entered a horse-drawn carriage. He was travelling to London, a journey at that time which would take almost 24 hours, and to a place which he had never before visited. Indeed, he had never ever previously been much more than twenty miles from the port in which he had been born. Not only was this journey to be his first to take him a significant distance from home, it was also a journey which was to change his life forever and in ways which he could never have imagined. This young man was James Paget and he was planning to stay in lodgings in the capital for an indeterminate period. A love of science and family were at the still centre of the young man’s being. As he travelled, he would certainly have been thinking about his own contribution to the knowledge of the natural history of those areas of Norfolk and Suffolk around his home as well as of the family which he was leaving behind.

***

His parents were Samuel Paget, a self-made business man, and his wife Sarah. They had married in December, 1799 when Samuel was twenty-five and had moved immediately into a large old house on the South Quay in Yarmouth. Samuel had only received a very basic education but had taught himself to be proficient in reading, writing and numeracy. On leaving school he had gone to work as a clerk to a merchant supplying provisions to the North Sea fleet. His employer died suddenly when Samuel was seventeen. Amazingly, for such a young man, he recognised an opportunity for self-advancement, made the long journey to the Admiralty in London alone, and demonstrated such a thorough knowledge of the business that he was told that he could continue to hold the contract if he so wished. Initially, he had had to borrow money to operate but so quickly did he impress the Admiralty with his

White Admiral No 72 21

efficiency in fulfilling the original contract that he soon ended up with additional, lucrative contracts enabling him to pay off his loans. By the time of the marriage he had become a rich man and was very busy as a brewer, large ship-owner and one of the chief business men in Yarmouth.

James Paget

James Paget

Over the next twenty-six years, seventeen children were to be born to them of whom only nine were to survive. Between 1800 and 1813 eleven children were born, five of whom survived to grow up – Martha, Frederick, Arthur, George and Charles. In 1812–1813, such was their wealth, they had built a magnificent new house on the site of their old one and it was there on January 11th, 1814 that their next child, our young traveller James had been born, to be followed by two more sons, Frank and Alfred, and finally Kate.

The Paget sons were the focus of all the attention within the household. At this time and in a male-orientated society, wealth passed down the male line so despite being born into a rich family, with so many brothers there was no chance for the daughters Martha and Kate to achieve financial independence; they became ladiesin-waiting trapped in the fine house on the Quay, waiting for a chance encounter with a socially suitable and wealthy gentleman who would want to marry them and thus enable them to leave the family home. If no suitable suitor turned up, the only honourable and viable alternative they had to becoming penniless old maids, would be to become governesses.

James was to enjoy all the privileges which wealth could buy – his own nurse, a huge playroom, and a house full of servants to wait upon him and a horse and

White Admiral No 72 22

carriage in which to ride. With Waterloo in 1815 and the end of the Napoleonic Wars , peace-time Yarmouth had settled down to trade and expand and James’ formative years were to be spent during the period of his father’s greatest affluence and influence. But it was not wealth alone which contributed to James’ apparently idyllic young life; it was the loving family members among whom he found himself and who nurtured him so capably and whose various members existed in a kind of spoked wheel-like symbiotic relationship in which all contributed towards the wellbeing of each other with Samuel and Sarah at the hub passing on their observable qualities to their children on the rim. They were truly good parents in every sense of the word.

Samuel was rather small, handsome and a thorough gentleman; cheerful, wellmannered, peace loving, and hospitable, temperate, refined in conversation, and a lover of all that was simply beautiful in literature and art. He was also calm and gentle in manner always seeming to love more than anything else the quiet of his home. As a business man, he was punctual and hard-working, and people considered him perfectly fair, liberal and honest. Such qualities made him an ideal candidate for mayor of the town and this he had become in 1817.

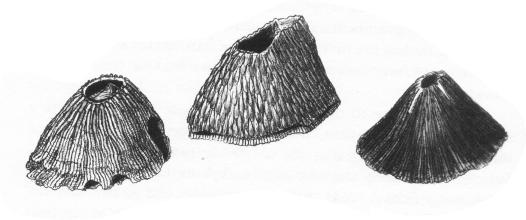

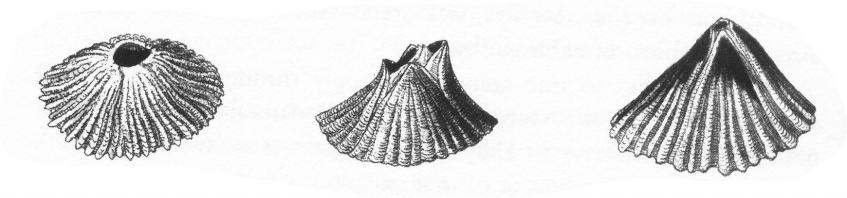

Sarah was a fine-looking, tall and graceful woman; she was resolute, strongwilled and strong in speech, characteristics not normally welcomed and approved of in a woman at this time. She had great appreciation for all that was beautiful in art and nature. She was skilled in writing, needlework and oil-painting and was a prolific sketcher, filling countless albums with her work. As was becoming increasingly fashionable at that time, she collected “everything” – autographs and seals, caricatures, shells, corals, agates, old china and glass and “curiosities” including all that she could persuade the masters of her husband’s ships to bring home from their long voyages. Each collection was beautifully arranged and was labelled in her own exquisite handwriting.

But the quality which James best remembered her for was her intense love of her children, for in spite of the nanny and the servants, she took close charge and guidance of them all; she was the most motherly of women. Of all her various activities, there was not one which she did not neglect or put aside when one of her children was ill or unhappy, or on the point of leaving home for any time, or upon a return from absence. Whilst away, a child would receive regular letters with home news and loving messages written in her beautiful handwriting and James was looking forward to receiving these in London.

James and his brothers were educated at a school in Yarmouth run by a Mr Bowles where the standard of teaching was such as to fit a young man for entrance to a public school and the three eldest brothers went on to Charterhouse. But by the time the four younger sons were of an age to leave Mr. Bowles’ school, Samuel Paget’s business empire was crumbling. There was increasing competition in Yarmouth between those involved in running shipping companies and breweries which inevitably resulted in some, including Samuel Paget’s, becoming far less successful than others. Samuel was respected as an honourable man and he was well liked by everyone, including the poor of the town. But such qualities were no longer

White Admiral No 72 23

particularly advantageous in the increasingly cut-throat world of commerce which now prevailed as the population of Yarmouth grew. Samuel had a very large family and he had always treated them very generously and educated them expensively. Money had originally been no object but now the debts were accumulating and he was becoming poorer by the day. This decline in the Paget family’s fortunes meant no more public school education for its sons and the four younger sons, including Charles and James, remained at home after they left school.

Samuel Paget when wealthy had built up a considerable library not for his own use, for he was far too busy, but for the use of his children whatever might be their choice of study. Among his botanical books were the great “English Botany; or coloured figures of British plants” (1790-1814) of Sir James Smith and James Sowerby in 36 volumes with 2,592 coloured plates of all known Phanerogams and also Dawson Turner’s beautifully illustrated book on seaweeds which James knew as the “Historia Fucorum” (1808-1819). Both Charles and James had inherited their mother’s love of collecting and natural history; now Charles became the entomologist of the family and James the botanist.

In 1824, when eleven, Charles had been kept back at school by a very long illness and had been attended by the family doctor, Mr. Charles Costerton. Fortunately, he survived and after leaving school he had been content to stay at home in Yarmouth to work with his father and younger brother Frank to try to turn around the failing business, now appropriately named Paget & Sons. By the time of James’ departure for London, Charles had devoted around six or seven years to the study of the insects around Yarmouth and, aided by the valuable identification books in the family library, had steadily compiled a long and very impressive list.

A naval career had originally been planned for James when he left school but it was then decided that he should be a general practitioner or something in the medical profession. Accordingly, in 1830 aged sixteen, he had been apprenticed for the then standard five years to Mr Costerton their well-educated family doctor, with the proviso that the last six months should be spent in hospital-study in London. Although much of his daily work during the four and a half years had been dull, tedious and apparently useless, he had also learnt things of great utility – dispensing and a practical knowledge of medicines and how to make them, account-keeping, the business-like habits needed for practice and the need for care, neatness and cleanliness in all minor surgery. He had also learnt the importance of careful observation as he was taught the anatomy of bones, dissected internal organs and portions of those limbs which he had recently seen amputated without anaesthetic. He had watched operations carried out by his employer and other surgeons in the town and had look closely and critically at the different methods of treatment. Above all else his apprenticeship had given him the opportunity to study science and he read avidly and voraciously, learning in the process the art of reading quickly. Apart from the standard medical text books available to him and current issues of “The Lancet”, he had immersed himself in botany having been initially encouraged towards this by a nephew of Mr Dawson Turner and subsequently by his son-in-law Sir William Hooker, the then greatest English botanist with whom he had gone on to

White Admiral No 72 24

correspond and exchange specimens.

During the course of the apprenticeship he had made a nearly complete collection of the flora of the district including the seaweeds washed up there. He had collected chiefly on Saturday afternoons but also at any free moments during the day, including before breakfast. He had given so much time to his botanizing that one old lady of Yarmouth who had observed his collecting activities was moved to say that he walked about too much to be a student of medicine !

Over these years, James had also meticulously collated at first-hand from local collectors, all the records of the flora and fauna of the Yarmouth area which he could gather. As a result, he and Charles had come to realise that this presented a golden opportunity for them not only to make their début as scientific authors, but more importantly to make some money to aid their ailing family fortunes by publishing all their records in book form. So James had set to work on a manuscript. He began with an outline of the study area, its habitats and the groups of organisms included in the book and followed this with a systematic catalogue of species and their known localities for which Charles had written the section on insects. He had checked the manuscript one last time before departing for London and now it fell to Charles to oversee its production at Mr Skill’s printing works in the town.

Many memories and thoughts must have raced and flittered through the young James Paget’s excited mind during that long journey but as the coach approached the capital they would almost certainly have become inexorably channelled towards the reason for his trip. Despite his determination to succeed at his chosen vocation and the self-confidence which had originally been created and fostered in him by his parents and which had been strengthened further by the success which came from his own efforts; despite all this, his mind must have forced him to focus apprehensively on the reason for his trip. And the reason was that in a few days he was to enter the prestigious St. Bartholomew’s Hospital as a pupil.

To be continued.

White Admiral No 72 25

***

David Nash 3 Church Lane, Brantham CO11 1PU

STAG BEETLE RESEARCH UPDATE

Road casualty survey results 2008 - provisional analysis

2008 was the final year of the stag beetle road casualty survey, which was first carried out in Suffolk with 10 volunteers in 2000. Since then stag beetle road casualty data have been collected annually (except for 2002) from Suffolk and a number of other counties.

19 volunteers returned stag beetle road-casualty data, 16 returns were from Suffolk,

2 returns were from West Sussex and one from Surrey,

23 road belt-transect data sets were returned,

6 transects yielded a nil count over the season.

Table 1. Numbers of beetles counted in the 2008 roads survey

A total of 371 stag beetles (or their remains) was observed on the roads. The number of times a route was surveyed varied from 6 to 83, the average being 30.

13 volunteers surveyed throughout the ‘stag beetle season’.

11 volunteers surveyed at least once every 4 days throughout out the stag beetle season.

4 surveyors surveyed daily throughout the stag beetle season. The total number of road casualty and live stag beetles observed along an individual transect over the stag beetle season varied from 0 - 91.

Excluding beetles where the sex was not identified by the surveyor (Unident.), female beetles killed on the roads outnumbered males in a ratio of 2.8: 1. Previous stag beetle road casualty surveys (Hawes 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007) show a female to male ratio of 3.5, 2.4, 3.4, 2.2, 1.6 and 3.1:1 respectively. The mean ratio of female to male stag beetle road casualties for the years 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 (excluding those where sex was not identified) is 2.7: 1.

Of the 61 stag beetles whose sex could not be identified by the surveyors (corpses too damaged; tibia of front legs not examined; genitalia not examined) the proportion of females to males is to date unknown.

Comments and discussion

Six transects gave zero sightings.

24 stag beetles of unidentified sex were collected and recorded along one surveyor’s

White Admiral No 72 26

beetle road casualties Live Stag beetles observed on roads Male Female Unident. Total Male Female Unident. Total 54 151 61 266 39 66 0 105

Male ratio = 2.8: 1

Male ratio = 1.7: 1.

Stag

Female:

Female:

transect.

Surveyors have submitted the stag beetles (and remains) collected to the author, so that foreleg tibia, and genitalia can be used to determine sex, where this is needed.

Annual index of abundance

Analysis of the data collected in the eight years of the survey is underway (the data submitted in 2001was incomplete and will not be included in the final analysis). The aim is to produce an annual index of abundance for each transect site, which will be included in a paper to be entitled ‘Development of non-invasive monitoring methods for larvae and adults of the stag beetle Lucanus cervus’ which will be submitted to the Journal of Insect Conservation in early March 2009.

Table 2. Stag beetle road casualty surveys: cumulative totals for 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008

Further analysis

? = sex of stag beetle not identified at present

Further analysis of the stag beetle road casualty survey data is being undertaken in 2009 to:

Compare transects where stag beetle road casualties occurred with control transects where no stag beetles were observed.

Compare landscape characteristics which might facilitate stag beetle road casualties, e.g. proximity of decaying tree stumps, dead wood in hedgerows, proximity of houses and their gardens, etc.

Predict where stag beetle road casualties are likely to occur, using landscape features, accumulated day temperature and soil type as pointers. Preliminary findings suggest that stag beetle road casualties occur more frequently in residential areas than in the open countryside.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to all the volunteer surveyors who took part in the 2008 survey and especially to those* who have contributed to all seven surveys referred to above.

Suffolk: Janet Baker, John Baker, Janet & Jim Buis, Malcolm Cook, Bob Deex, John Glazebrook, Doug Harper*, Rosemary Milner*, Nicola Moxey*, Naomi Newton, Gill & Chris Pink, Ann Ratford, Keith Rawlings, John Tombs*, Mark Usher; Sussex: Norman Allcorn, Miss C.P.S. Griffiths; Surrey: Mark Wagstaff. Any errors and omissions in the above are the responsibility of the author.

White Admiral No 72 27

Colin Hawes Stag Beetle Road Casualty Co-ordinator & Surveyor 141 830 321 351 1502 352 207 561 2063 Female Male ? Total Female Male Total ? 2 Stag beetle road casualties Live stag beetles observed on road transects No. of road transects Total beetles observed

TREE FERN ALIENS

In the Spring of 2006 my field work was ended abruptly one day by very heavy rain. I decided to look at some indoor plants and went to the Exotic Plant Company at Aldeburgh. In one of their poly tunnels are some large tree ferns (Dicksonia antarctica) and at the base of the trunk of two of these I found patches of a moss. It looked unfamiliar and turned out to be a southern hemisphere species Leptotheca gaudichaudii. The manager of the plant centre was surprised that I had found anything of this nature on the tree ferns because he said that they underwent such a thorough cleansing before import that he had heard of plants being killed during the process. A short time later I went to another garden centre, at Coggeshall, that specialises in similar plants and found Leptotheca gaudichaudii on some of their tree ferns, again Dicksonia antarctica. At this centre there was a bundle of recently delivered tree fern trunks that were completely clean with no sign of any moss.

When browsing round a garden centre in north Suffolk May 2008 I came across a display of tree ferns. These were a mixture of Dicksonia fibrosa and D. squarrosa and were about 50cm. tall. All had some mosses and liverworts growing on their trunks. Some were familiar things that are common in Suffolk such as the mosses Eurhynchium praelongum and Leptobryum pyriforme and liverworts Lophocolea bidentata and Marchantia polymorpha. There were also others that were unfamiliar and in all I was able to identify three mosses Archophyllum dentatum, Leptotheca gaudichaudii and Wijkia extenuata and four liverworts Chiloscyphus coalitus, Lejeuna primordialis, Lophocolea muricata and Teleranea longii. These are all southern hemisphere species and are fairly common in New Zealand. The tree ferns had been imported from Holland and bore the trade name Ponga. I think they must have been imported ready potted and with the bryophytes already well developed. Perhaps there are fewer restrictions on importing tree ferns via Holland rather than direct from New Zealand or Tasmania.

Introduced bryophytes occur in glasshouses in a number of botanical gardens. The moss Leptotheca gaudichaudii has been found growing on the trunk of tree ferns in a garden in Ireland and Archophyllum dentatum amongst filmy-ferns in a damp grotto in a private garden in Cornwall. Also present at this site is an Australian species of filmy-fern Trichomanes venosum, which is thought to have been introduced with tree ferns in the last century.

With the current popularity of tree ferns I began to wonder if any of the bryophytes that I had been seeing in garden centres would survive after being planted in gardens locally. The answer came sooner than expected when I visited the gardens at East Bergholt Place. In a damp area close to a small lake are some fairly large specimens of Dicksonia antarctica and on the base of two of them I found the mosses Archophyllum dentatum and Leptotheca gaudichaudii and the liverwort Lophocolea muricata. Mr Rupert Eley the owner of the garden tells me the tree ferns were planted between four and five years ago, so it is possible for these introduced species to survive given the right conditions. At East Bergholt the tree ferns are planted in an area that remains damp throughout the year, tree cover provides protection in

White Admiral No 72 28

summer and in February the fronds of the tree ferns die and hinge downwards adding further shelter round the base of their trunks.

Bryophytes are unlikely to be the only things imported with tree ferns, so what other strange things are out there waiting to be found?

References

Rumsey, F. J. Archophyllum dentatum (Hook. f. & Wils.)

Vitt & Crosby. Naturalised in Britain. J. Bryol. 23, 341-4 2001.

Smith, A. J. E. The Moss Flora of Britain and Ireland. 2004. CUP.

Richard Fisk

MICHAEL MAJERUS (1954 - 2009)

Professor Michael E. N. Majerus (1954-2009) was a geneticist and Professor of Ecology at the University of Cambridge, an enthusiast who became a world authority in his field of evolutionary biology. He was widely noted for his work on moths and ladybirds and as an advocate of the science of evolution as well as an enthusiastic educator and the author of several books.

Mike took an early interest in lepidoptera and ecological genetics following the work of E.B. Ford, whose book Moths (in the New Naturalist series) he bought at the age of ten. Later he moved into studying ladybirds, an area which brought him widespread publicity as an expert in 2004 when the Harlequin ladybird came to Britain, causing a disaster for native species. This publicity meant that members of the public were able to be involved in effective monitoring of the spread of the Harlequin. His work on the peppered moth provided new support for the understanding of peppered moth evolution.

He was the president of the Amateur Entomologists’ Society and a Life Fellow of the British Naturalists’ Association. He received a number of awards, including the Sir Peter Scott Memorial Award in 2006, for contributions to British Natural History.

He was a good friend and supporter of the SNS. Members who attended the AGM in 2006 will long remember the wonderfully erudite and entertaining talk he gave on the harlequin ladybird.

He died on January 27th, 2009 after an unexpected and brief struggle with aggressive mesothelioma.

White Admiral No 72 29

BOOK REVIEWS

Arable Bryophytes. A field guide to the mosses, liverworts and hornworts of cultivated land in Britain and Ireland by Ron Porley. Published by WILDGuides. 2008. £17.95

The first meeting that I attended after joining the British Bryological Society was a workshop given by the late Dr H.L.K. Whitehouse at which I was introduced to the various bryophytes that can be found in arable fields. I have been fascinated by them ever since. Those of you who attended the last SNS conference will have heard Chris Preston talk about a survey of bryophytes of arable land carried out by members of the BBS. It was Ron Porley (co-author of the New Naturalist volume on Mosses and Liverworts) who first proposed that survey. He has now produced a field guide to the various species to be found in cultivated land. It is a genuine field guide being just 8.5 x 5.9 x 0.5 inches so fits one’s pocket and has a plastic cover. It begins with a chapter explaining what a bryophyte is, hints on identification and conservation. Each of the forty-seven species described is illustrated with a colour photograph, a distribution map and, where appropriate, additional drawings and an indication of its size. It is actually a good introduction to bryophytes for any naturalist: many of the species are common and easily found, even in ones garden, and the excellent photographs make identification fairly easy. In his foreword Jonathan Sleath the President of the BBS says ‘The guide has been painstakingly compiled, is beautifully illustrated and presents a thorough understanding of the taxonomy, distribution and ecology of arable bryophytes. It is difficult for me to commend it too warmly’. I can do no more than agree with that.

Richard Fisk

Barn Owls in Britain by Jeff Martin. 288 pp with 35 b/w illustrations. Hardback. Published by Whittet Books Ltd. 2008. ISBN-13 978-1-873580-75-2 £15.99

There are few people more passionate about Barn Owls than Jeff Martin and this comes across strongly in the book. Jeff covers a number of topics including: Barn owl biology, diet, distribution, movements and history; he also hypothesises on the reasons for the Barn Owl’s apparent decline.

Despite some inaccuracies, the chapters that cover the owl’s distribution and biology are well researched and well written. Jeff’s knowledge gained when serving as Suffolk Mammal Recorder stands him in good stead and he excels in the chapter titled “The food of the barn owl”. Much of his research is based on pellet analysis collected by researchers at localities throughout Britain. Those that supplied their findings are fully acknowledged. Generally, however, I found little original material, although a bibliography, appended to each chapter, details the sources of information.

Barn Owls in Britain holds a wealth of information. It is presented in a neat,

White Admiral No 72 30

hardback book that is well laid out. The cover is adorned by a superb David Hosking photograph of a Barn Owl bringing in prey. The text is complemented by cartoon-like vignettes together with a number of maps and Tables. It is a good read, but in places I found it difficult to follow as many sentences ramble on. One in particular rambles for a mammoth 68 words (p.109) and there are many of 40 or more. I found this distracting and it’s such a pity that punctuation wasn’t highlighted by the proof readers.

Jeff makes frequent references to his “Suffolk study”, but it is difficult to ascertain just what this study involved. The aims and objectives needed better definition and any results properly summarising.

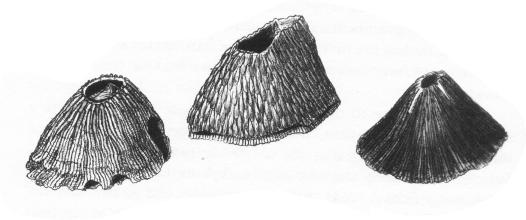

The chapter titled “The first barn owls in the British Isles” is fascinating, only loosely connected to barn owls, but fascinating. Jeff starts by detailing evidence of apparent barn owl remains found in fossils dating back to prehistoric times. He then goes though the ages describing the Ice Age, the Romans, Dark Ages, Black Death, etc, etc.

In places, the book is well out of date and doesn’t concur with current thinking. For me, the most worrying aspect is in the chapter titled “The challenges”. Here Jeff champions the use of nest boxes as if he were the first to suggest their use. He also includes two drawings of totally inappropriate design. It is well known that the old “tea-chest” design with the entrance hole at the bottom has been responsible for the deaths of many owlets. Young chicks are known to become alert and then rush towards the entrance hole as their parents bring in food. Those that are nudged to the ground would perish as barn owls seldom tend their young outside the nesting chamber. The entrance hole should be at the top of the box. I would defy any barn owl to get food into the upright nest box without the use of a landing platform!

Jeff questions the validity and identification of the dark-breasted barn owl (Tyto alba guttata) that occurred at Landguard Point on 11th June 1997. Jeff didn’t examine this bird, so his opinions ought to have been more reserved. Since the publication of the book, there has been a record of a female, Dutch-ringed, darkbreasted barn owl that nested in Norfolk. Of course, Jeff didn’t have the benefit of hindsight.

I would like to have seen a chapter on conservation, detailing the work of The Barn Owl Conservation Network and research carried out in association with the Barn Owl Monitoring Programme. There could have been more written about the many projects that are being carried out throughout Britain designed specifically to encourage a population increase and range expansion.

Overall, I did enjoy reading the book and I was particularly impressed with the compilation of information that is readily available. The book is heavily biased towards Suffolk and neighbouring counties, so is the title “Barn Owls in Britain” misleading? However, if this means that more copies are sold and it further promotes interest in the conservation of the barn owl, then it has my vote.

Steve Piotrowski Author of The Birds of Suffolk, Project Manager for Suffolk Community Barn Owl Project

White Admiral No 72 31

A HERBALIST’S VIEW OF THYME

There are many species and subspecies of thyme, exemplifying the Darwinian principle of divergence from a common ancestor as adaptations occur to exploit varying habitats and niches. Three species are considered native to Britain, but the species used by medical herbalists is the garden thyme, Thymus vulgaris. This, therefore, is the species I shall discuss, but it is likely that the native species will contain similar compounds, with similar potential for medicinal use.

Thymus vulgaris is a native of the western Mediterranean region, east to S.E Italy. It was being cultivated in Britain by 1548, but was probably here long before that. It is now widely naturalised, with the frequency of records increasing.

Like many Mediterranean species, thyme contains a pungent and volatile essential oil. This oil contains many constituent compounds including thymol and carvacrol to name but two. These compounds give the oil strong antiseptic properties. It is active against bacteria and fungi. Thyme tea or diluted thyme tincture makes an effective gargle for sore throats, laryngitis or tonsillitis, and can be taken internally for infections of the lungs. It also has expectorant properties and is a soothing remedy for irritable coughs. Hence, at this time of year, I do a brisk trade in Thyme and Liquorice syrup. I shall leave liquorice for a future edition.

Caroline Wheeler

SNIPPETS

• The rare Smooth-stalked sedge has been found at SWT’s Market Weston Fen, a first confirmed record for Suffolk. Martin Sanford says it is known at one site in Norfolk and only a few in Essex. “Its distinguishing features include small red dots on the fruits which themselves are only a couple of millimetres in size.”

• Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses are hollow, what have you found?

• Multiple paternity (two or three fathers) was found in 53.8% of litters of the Wood Mouse studied at Queen’s University, Belfast. Polyandry increases the genetic diversity of litters, thus improving the chance of survival in times of stress.

• A letter written by Charles Darwin has been discovered in the archives of Ipswich museum. The letter, dated 29th August 1872 was found at Ipswich museum in February 2009, and is in reply to F.W. Harmer, an amateur geologist from Norwich. Darwin apologises that Mr Harmer has become “involved in a troublesome controversy” over an article on natural selection. Harmer had defended Darwin in a newspaper debate with W.P. Lyon, author of ‘Homo versus Darwin’, in which he wrongly claimed Darwin had said “natural selection is a kind of god that never slumbers nor sleeps”. The letter is on

White Admiral No 72 32

LETTERS, NOTES AND QUERIES

Dialect names of birds

Around the Essex coast are several small saltmarsh islands called either Pewit or Pewet Island and an idle passing thought might assume that they are associated with the Peewit or Lapwing Vanellus vanellus. However, a more lingering consideration may bring the realisation that this is an odd association. Lapwings are not really saltmarsh birds – they are very much more associated with farmland in East Anglia. The truth about the island names was revealed by one of my colleagues, thumbing through some very old copies of the Journal of the Essex Field Club, Essex Naturalist. Apparently, then at least, “Puit” was a local name for the Black-headed Gull Larus ridibundus. This makes sense: the various saltmarsh islands are or were known breeding and roosting sites for these birds. Another local name for the Blackheaded Gull was Cob and there are also instances of Cobmarsh Island and the like, accordingly.

I would be interested to learn if this name of Puit was, or still is, used in Suffolk. The Ordnance Survey maps I have scanned do not reveal any Pewit Islands along the Suffolk coast, although the geomorphology here is not so predisposed to the formation of saltmarsh islands in estuaries as is the Essex coastline.

The Old Museum

I have just read White Admiral 71. I expect you’ve had other replies like this. The old museum is being developed by the same local couple, the Amblers, who started Mortimer’s fish restaurant first on the waterfront where the Bistro now is, then at the converted electricity substation, before selling out to Loch Fyne not too long ago. Bob Entwistle (Senior Conservator at the Museum) told me they bought the old display cases from the museum to convert for use in the new restaurant.

As it’s now 100 years since the old museum opened, this reuse is a timely celebration as the new owners are apparently keenly aware of their heritage.

Stella Wolfe

P.S. I have now heard that the place, to be called “Arlington’s” after the ballroom once there, is now open.

White Admiral No 72 33

Adrian Knowles, Jessups Cottage, London Road, Capel St Mary, Ipswich, IP9 2JJ

Lemmings in Suffolk?

At various times over the last two years, a short stretch of pavement in Capel St Mary has been littered with up to seven dead bodies of voles and mice, at different stages of decomposition. Curiously, this stretch of pavement is only about 30 feet long and is shown in the photograph below. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the unfortunate mammals have fallen to their deaths over the parapet above and it is quite striking the I have never seen a corpse so much a one foot to the right of point B – they all lie between points A and B.

If this assumption is correct, what drove them to their deaths? The occurrence seems to go in sporadic bursts, rather than a steady stream of casualties. Were they fleeing from predators such as weasels and stoats, hunting in the verge above? If so, why don’t the predators cotton on to the fact that an easy supper lies awaiting at the bottom of the adjacent grassy slope? The bodies just lie there and slowly rot down. None of the more intact bodies examined shows any sign of outside injury.

I’d be interested to here any views on this phenomenon. Subject to road traffic safety, it might be interesting to examine other similar parapets to see if the same thing happens there.

White Admiral No 72 34

Adrian Knowles, Jessups Cottage, London Road, Capel St Mary, Ipswich, IP9 2JJ

Holes between paving stones: follow-up

Alan Beaumont may well be right in saying (White Admiral 71, page 10) that the insect seen nesting in the ground between paving slabs was the digger wasp Crabro cribrarius, although there are other possibilities, such as the digger wasp Mellinus arvensis, with the latter perhaps more often utilising compacted horizontal ground. Both of these species provision their nests with flies, including hoverflies.

A well-trodden path would appear to be a frustrating place within which to excavate a nest tunnel, with every footfall at risk of kicking loose material back down the hole from whence it was mined at great effort. Such holes must also make small but effective plug-holes down which any heavy rainfall might easily drain, especially if puddled-up on a compacted path. However, several species of solitary nesting bees and wasps choose to nest in such places. Perhaps the most prolific exploiter of this micro-habitat is the digger wasp Cerceris rybyensis (I might also refer the reader to the same issue of White Admiral, page 32). Hard paths across heathland or other sandy places can be copiously punctuated by the miniature “volcanoes” of sand being dug out by this species. However, this species generally preys upon small mining bees and so is unlikely to be the insect observed by Alan. Several mining bees within the Genus Lasioglossum will also nest in hard, compacted ground.

One of Britain’s rarest digger wasps is Cerceris quadricincta. This has seemingly always been a speciality of the Colchester area and the 1903 Volume 1 of the “Victoria County History” for Essex notes that the species is “mainly an urban insect, for it forms its burrows in the public streets where, owing to alterations, two colonies have been destroyed recently”.

Following on from this, one might answer Alan’s question about whether or not his observation was another case of urbanisation of a species by suggesting that it is more likely to be another case of man paving over another insect’s habitat...

Adrian Knowles

SNS Hymenoptera Recorder, Jessups Cottage, London Road, Capel St Mary, Ipswich, IP9 2JJ

White Admiral No 72 35

RECORDS PLEASE

The Hairy-footed Flower-bee Anthophora plumipes

During March and April, as the weather warms and plants such as Lungwort (Pulmonaria sp.) and Aubretia come into flower, many insect begins to stir. Amongst the early bumblebees is another bee and one that looks superficially like a bumblebee. This is the Hairy-footed Flower-bee (see Plates 5 and 6 p.19, for pictures of females and males, respectively), which leads a solitary existence in contrast to the colonial, social bumblebees. At about 13mm long they are a little smaller than most bumblebees and they fly with very quick wings in a swift and darting flight, frequently hovering in front of flowers and so have a rather different “jizz” to their larger relatives. They are perhaps more reminiscent of rotund hairy hoverflies in their behaviour. They nest in tunnels excavated in steep, dry soil banks and occasionally within the crumbling mortar of old masonry, as do several other solitary bees. Amazingly, they emerge from their pupae in late summer but remain in their sealed nest cells until the following spring – about 6 months spent as an adult just standing still!

The females are all black, with yellow/orange hairs on her hind legs (you may need to look carefully to avoid confusion with bees bearing yellow pollen on their hind legs). The males are strikingly different, with dark orange/brown hairs towards the front of their bodies, giving way to black hairs anteriorly. If you find two insects matching these anatomical and behavioural descriptions together in your spring flowerbed then there is little doubt that you are looking at this species.

I would be pleased to receive any records from members and would be happy to verify any photographs if the file size is less than 200k – not all of us are on broadband! Please submit your name and address and, if possible, an Ordnance Survey grid reference for your sighting and the date on which it was made. Details of the sex of the insect and the flowers they were visiting would also be useful ecological information, along with any nesting observations.

Adrian Knowles Jessups Cottage, London Road, Capel St Mary, Ipswich, IP9 2JJ

Contributions

Please send items for publication in the White Admiral newsletter to the Editor at the address on p.1.

Deadlines for copy are 1st February (spring edition), 1st June (summer edition) and 1st October (autumn edition).

The opinions expressed in White Admiral are not necessarily those of the Editor or of the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society.

White Admiral No 72 36

James Paget

James Paget