7 minute read

Tan Siuli: Violent Attachments

Art Museum Senior Curator Tan Siuli speaks about Violent Attachments, the upcoming group show she is curating for Sullivan+Strumpf Singapore.

Violent Attachments explores the deeply embedded nature of violence, and mankind’s conscious as well as subconscious attachment to violence in its myriad forms. The term has currency in both psychoanalytic and political theory: in 1992, Dr Reid Meloy’s publication of the same name looked at why so much of human violence occurred between people involved in an attachment paradigm. More recently, Dr Hagar Kotef’s similarly titled essay (2019) examined subject positions that are contingent on the exercising of violence on others, and how entire communities and political identities are sustained through these violent arrangements. These texts point to a painful recognition that violence -- although widely deplored as abhorrent - may in fact be deeply ingrained in the human psyche, infiltrating our most intimate relationships as well as broader political and social relations. It shapes a sense of self or subjectivity, and the very notion of ‘attachments’ implies the inextricable psychological, social, as well as structural investment in forms of violence.

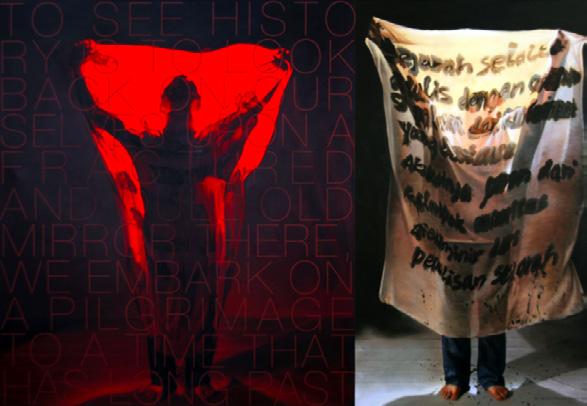

FX Harsono, Tracing History 2, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 210 cm

Collectively, the artworks in this exhibition explore various notions of and around violence, in particular how mankind’s various attachments are ultimately violent, and how painful histories may be renegotiated, especially those in which violence has become a conditioned part of one’s identity.

Adeela Suleman’s delicate miniatures posit violence as endemic, historical, and continuous. Her works draw on the artistic traditions and iconography of classical South Asian art, presenting aestheticised scenes of decapitated figures doing battle as a commentary on the volatile realities of life in contemporary Pakistan. With their references to Mughal painting – commonly feted as Pakistan’s crowning cultural achievement – her works suggest an illustrious lineage of violence, and one that is embedded in the psyche of the people. Some of these images are served up on vintage dinner plates thrifted from Karachi’s markets, and beautifully framed as decorative vignettes that might decorate a domestic interior. The seepage of these scenes of violence into the home, as well as their aestheticisation, raises troubling questions about the spectacularisation of violence in contemporary media culture, as well as how violence might be rendered ‘palatable’ through representation, and made ‘acceptable’ to a desensitised audience as an intrinsic part of communal or national identity.

As a philosophical counterpoint, Lindy Lee’s bronze sculpture is less direct in its invocation of violence, which manifests itself implicitly in the artist’s gesture of flinging molten metal. Here, ‘violence’ is an artistic expression reminiscent of the vitality of abstract expressionist painting as well as the tradition of ‘splashed ink’ paintings in Zen art. Left to chance, the uninscribed ink, paint, or liquid metal acquires its own agency, its seeming formlessness open to a multitude of interpretations. Read in proximity to Suleman’s vignettes, the splattered bronze on the wall mirrors the fountains of blood spurting from the decapitated figures; a visual echo of the clamor of steel on steel. At the same time, Lee’s work evokes an explosive splintering of form – perhaps that of a golden sun - suggesting the eventual decimation or end of life, as well as a ‘big bang’ heralding new beginnings in a cosmic cycle: an end to all things, as well as a coming into being.

Much of the work of pioneering Indonesian artist FX Harsono has centered on redressing histories of violence, inflicted by an oppressive regime on the citizenry at large, as well as more insidious and state-sanctioned forms ofinjustice targeting certain communities. Harsono’s earlier, strident works from the 1970s to 1990s rallied against the state apparatus’s often militant means of oppressing dissenting voices. From the 2000s, however, the tenor and focus of his work shifted to examine a different form of violence: that of the deliberate suppression and erasure of the culture and identity of the Chinese Indonesian community, of which he is a part. This was effected through more subtle, insidious means, such as a national legislation that compelled the community to adopt names that were more ‘Indonesian’, under the pretext of national unity. Harsono’s research has also uncovered histories of physical violence against the ethnic Chinese community in Indonesia - lacunae which he has sought to recuperate and redress through his art. Most poignantly, the charge that his work holds rests on his position precisely as a subject of this violence. In the words of Philip Smith, these experiences “(have) been stamped onto the very question of what it means to be Chinese Indonesian. To escape the trauma of what occurred, if such an escape were even to be possible, would entail cutting away any sense of Indonesian selfhood.”

A similar social commentary permeates Jakkai Siributr’s confrontational portraits, simultaneously a critique of mankind’s attachment to trappings of power as well as the superstitious excesses of popular Buddhism in Thailand. Following the convention of the Thai ‘funeral book’ – an album intended to commemorate the achievements of the deceased - Jakkai created a series of self-portraits in uniform, a reminder of the abiding influence of the military and police in everyday life and civil society in Thailand. These are forces of authority with a checkered history, invested with the power to enact punitive measures, the horrific violence of which has been explored by the artist in other works such as 78 and immortalised in harrowing images of the Thammasat University massacre. Jakkai’s works are hence a commentary on society’s attachment to these forms of power (and abuse of power), as well as the trappings of prestige and position. However, his take is satirical, for his subjects are garlanded with monstrous accoutrements that reference popular talismans designed to ward off envy and danger, and confer on their wearer luck, power and protection. The phalluses – a popular talisman known as the phalad khik – which confront the viewer speak to the vanity and violence of earthly desires (gambling luck, success with women), and the excessive attachment to material things, as opposed to the transcendence advocated by Buddhism. The amulets and protective yantras embroidered onto the subject’s uniform suggest a corrective for unconscionable acts, or a safeguarding against malign intentions and violence. Jakkai’s uniformed subjects appear weighed down by these various emblems of power, and his portraits suggest a desperate guarding against mortality and danger.

Likewise, an overwhelming ‘excessiveness’ may be found in the work of Eko Nugroho. His sprawling tapestries depict figures festooned with paraphernalia or various appendages masking their faces, making it difficult to discern their expression and, by extension, their intent. Imagery and iconography are densely layered, drawn from influences as varied as graphic novels and comics, to popular culture and traditional art forms such as wayang kulit (shadow puppet theatre). Having lived through remarkable watersheds in Indonesia’s political and cultural history, Eko is keenly conscious of social injustices and several forms of violence, including that against the environment; his art seeks to present his ideas around these issues in a visually accessible style.

One of his tapestries likens democracy to a garden, where an abundant variety of plants bloom and flourish, albeit chaotically; a note of disquiet is introduced by way of the humanoid faces peering out from between the foliage, as well as the wire fencing that cordons off a section of the garden, a subtle reminder of Indonesia’s not-so-distant past under the former political regime. Significantly, the brightly coloured leaves that dominate the image are those of the croton tree, which is usually planted on the fringes of cemeteries in Indonesia. In the background, just visible through a clearing in the foliage, is a ship carrying refugees, silhouetted against a blood orange sunset, a reminder of the violence that compels people to flee their homelands. Violence is conveyed in a similarly subtle but barbed way in Another Coalition #2, where two figures enact a pantomime of oppression and imbalances of power.

Just as violence manifests itself in myriad ways, so too have artists adopted various artistic and aesthetic strategies to represent and comment on its forms – from the explicit to the insidious – from differing perspectives and subject positions.

Violent Attachments opens August 27 at Sullivan+Strumpf Singapore. Email us for details.

Eko Nugroho, Another Coalition #2, 2019, embroidered painting, 271 x 156 cm

Hagar Kotef, “Violent Attachments”, Political Theory 48 (1): 4 – 29. Published online July 2019; Issue published February 2020.

J Reid Meloy, Violent Attachments, 1992.