6 minute read

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu: Making History

from Sullivan+Strumpf Contemporary Art Gallery Sydney & Melbourne, Australia & Singapore – Feb/Mar 2023

By Will Stubbs

History comes in many shapes and forms. We are tuned to history, which comes in books and ruins. Australian history is more intangible. In this case, it comes in epic song poetry and shards of pottery, which is not necessarily the history we’ve been told.

Underpinning Dhopiya Yunupiŋu’s first solo exhibition is the historical fact that European people were not the ‘first contact’ with Australians. There is significant archaeological evidence of this, including the important rock art site at Djulirri in the Wellington Range of Northwestern Arnhem, showing a yellow Makassan prau (boat) lying under a beeswax ‘snake’. The snake has been shown to have been laid down no later than AD 1664.

At the exhibitions heart, is an acknowledgement and appreciation of the ceremonies and rituals associated with the annual visits by Indonesian praus over hundreds of years. Makassar fishermen arrived each December to camp along the Arnhem Land coast to gather trepang (sea cucumber) for trade with China. People in China enjoyed eating trepang and believed that it also increased their sexual desires. By the mid-1800s, one-third of all the trepang eaten in China (about 900 tonnes) came from the Arnhem Land trade. Trepang is still used in China as food and medicine.

These sailors and gatherers of trepang from coastal waters, caught the seasonal winds back and forth from what is now known as Sulawesi. Yolŋu know this place as Maŋgatharra. During the trade, Yolŋu would visit Sulawesi and sometimes stay. Similarly, Makassan sailors would sometimes remain in the Top End, known as Marege. The relationship they had with the Yolŋu was amiable and productive. The trade was not just sourcing the product but a complicated processing technique of gutting, boiling, burying in the sand for a period and then drying in racks or smoking in small huts. Yolŋu were involved in all aspects of this industry as well as supplying the camps with firewood, food and water. The relationship extended to shared spiritual expression.

Until the turn of the last century the annual visitations of the Makassanese to the Top End shores of Australia were a lynchpin of the Yolŋu economy and society. These visits were banned by the newly formed Australian Government from 1901.

Dhopiya's father Muŋgurrawuy (Gumatj clan) was familiar with Makassan culture and drew a representation of Makassar City for the anthropologist Ronald Berndt in 1947. It is the stories handed down from her father that Dhopiya refers to directly.

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Galiku Buŋgul (Cloth Dance), 2022 natural earth pigments on stringybark 76 x 65 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

Many Gumatj places are connected to the trade including Maṯamata, Bawaka, Gunyuŋara,Galupa and Dhanaya. Epic Gumatj song poems reference Galiku (Cloth), the anchor, the Djiḻawurr (Scrub Fowl—known to frequent jungle beachside areas common to these Marŋarr) and the Tamarind, steel knives, märrayaŋ (guns), pillows, tobacco, flags, sail, cards, money, Djambaŋ (tamarind trees), Djolin (musical instruments) and Ŋanitji (alcohol).

The Gumatj homeland on Port Bradshaw is Bawaka but also known by its Makassan name Gambu Djegi, now understood as a translation of ‘Kampong Zikir’, Bugis for ‘a sacred village’. This place is an ongoing source of pot fragments buried in the sand which come to the surface after the Wet Season. The pots originated with the Torajan ethnicity rice and corn farmers who used the clay from their rice paddies and then fired them with the husks at the end of the harvest. They were traded to the Bugis seaman in their praus who used them to carry their supplies of water and rice.

The pots at Bawaka are the result the end of harvest ritual to smash the pots enshrined in songlines. The Makassans would hold a big feast and share their spare supplies prior to loading the ship with dried and processed trepang. The songlines end with the revellers 'butulu badaw!' (smashing the pots) at the end of the party. Bawaka is also associated with the female spirit Bayini who still inhabits this place. She may have been murdered here. She is a trickster who targets single men and covets gold.

Several of Dhopiya’s nieces visited Makassar in 1988 and met the elderly daughter of a Yolŋu woman who had followed her partner back to Maksassar but had been barred from returning home due to the 1901 embargo. From 2015, the renewal of the relationship intensified and the pots used in this exhibition were sourced from Sulawesi, from the Torajan artisanal tradition.

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Darripa djäma (Processing Trepang), 2022 pigment on terracotta ceramic 41 x 36 x 36 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

As the seasons of the year ran the same ageless cycles, so did the Makassan visits. Yolŋu sacred songs tell of the first rising clouds on the horizons—the first sightings for the year of the Makassan praus’ sails. The grief felt at the time of Makassan trepangers returning to Sulawesi with Bulunu (the S.E winds of the early Dry season) is correlated with the sunset. Djapana means ‘sunset’ in Yolŋu matha and ‘farewell’ in Bugis. The red sails of the Praus mirror the pink sunset clouds. The death of the Sun at day’s end equated in song with the grief at the passing from life of a member of the clan. The return of the Makassans with Luŋgurrma (the Northerly Monsoon winds of the approaching Wet) is an analogy for the rebirth of the spirit following appropriate mortuary ritual. This also correlates to the songs of the reborn morning Sun as it rises.

These handed down stories, poems and songs, speak of a centuries old economic and family history that surpasses Western experience, forming an integral foundation to Yolŋu people, and the subjects of the work by Dhopiya Yunupiŋu.

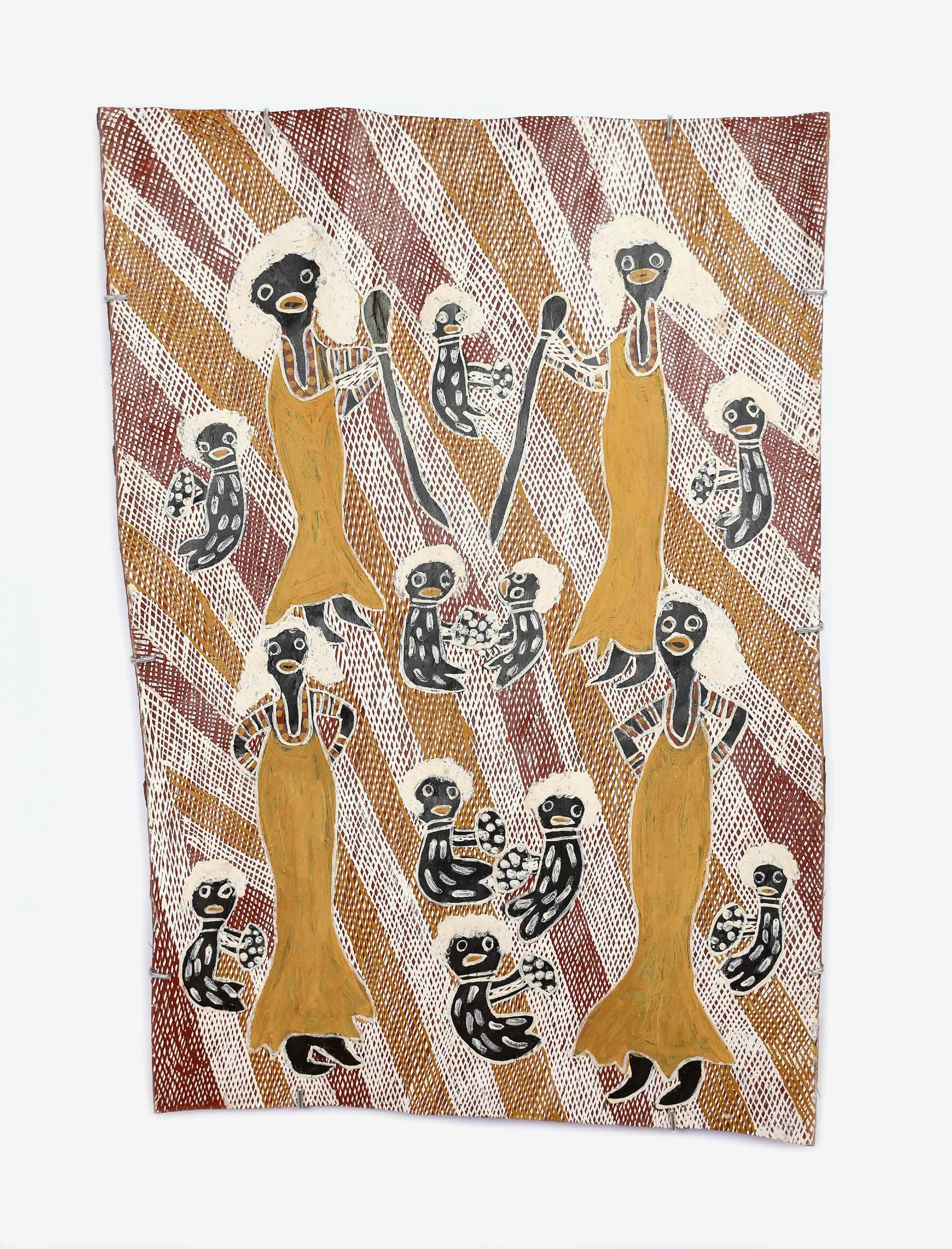

Dhopiya Yunupiŋu Bayini, 2022 natural earth pigments on stringybark 100 x 71 cm

Photo: courtesy of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre

DHOPIYA YUNUPIŊGU, 28 FEB – 24 MAR 2023, S+S SYDNEY

EMAIL ART@SULLIVANSTRUMPF.COM TO REQUEST A PREVIEW