5 minute read

KAYAKING IN THE WAKE OF LOSS

After four years, the Richmond kayaking community continues to mourn one of their own without losing love for the water.

BY LUCIE HANES

CHRISTIAN WOOD WAS PREPARED FOR THE WATER

conditions on his last day out on the James River. That’s the part that’s been the toughest for his friends and fellow boaters in the Richmond kayaking community.

As a teenager, Wood put in the effort to master his skills and dedicated himself to the sport from day one with unprecedented vigor, according to Michael Stratton, director of the Outdoors Program at Trinity Episcopal School, where Wood first began kayaking.

“I have never met someone as committed to a lifestyle as he was,” said Stratton, who taught Wood how to roll and knew right away that he would be an influential part of the river community. “He was all in. He watched every outdoor video, followed everyone on social media associated with outdoor adventure sports, and knew every single gear item that was trending. He was the most knowledgeable student I have ever met.”

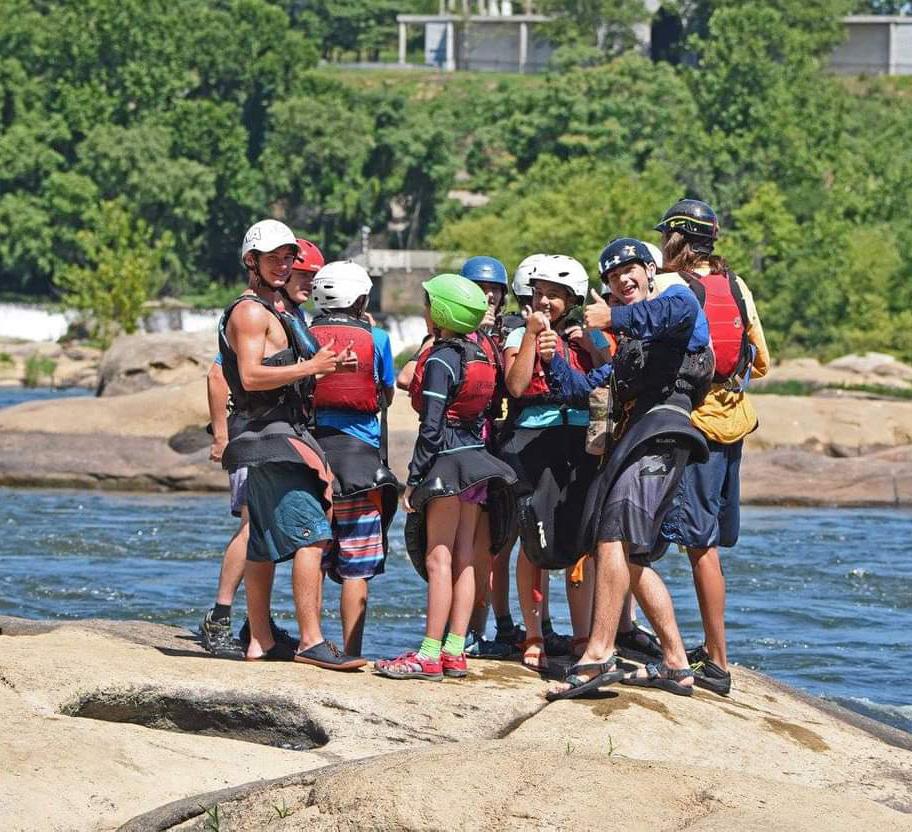

He also emanated enthusiasm for all aspects of kayaking, while paddling on his own time or as an instructor at Passages Adventure Camp.

“I think of Christian as endlessly energetic, but always knowing where that energy needed to go,” says Geoffrey Gill, the kayaking site director at Passages while Wood served on staff. “You could see it in his paddling style, just throwing in every move and every trick he could, but what stood out to me was how he directed it. He would take the lines he wanted to take, stop and play where he wanted to play, but still have an eye out for where the group was. I trusted his judgment to be in the right place and respond the right way.”

But paddling whitewater is unpredictable and carries inherent risks for even the most experienced boaters. On February 13, 2018, not long after his 18th birthday, Wood headed out on the Lower James with another equally experienced boater and friend. Both he and his paddling partner held valid high-water permits, which are required for everyone on the river when it rises above flood stage. Though the James presents a serious threat at such a high level, the pair had enough experience under the same conditions to feel confident in their decision to enter the water. Wood eventually collided with a log concealed under the surface, lost consciousness and endured the battering of the waves while his friend fought the current to attempt a rescue.

Wood’s partner managed to reach him, pull him above the water, and tow him back towards the shore—all against a raging current that most kayakers wouldn’t have the strength or the courage to face. He administered CPR on Wood until River Rescue showed up within minutes to take over. But after being taken to a nearby hospital, Wood later died.

“This was a tragic accident, but an accident no less,” said Kevin Tobin, the director of Passages Adventure Camp and owner of the Peak Experiences climbing center. Water levels presented dangers at the time, but the two boys knew the demands of the river in those conditions. “I believe Christian in no way acted rashly or took risks that he and his paddling partner were not prepared to take on. He was a talented and intelligent kayaker who knew his limits and trusted his skills to take him down the river successfully, every time.”

The Richmond kayaking community has had four years to sit with Wood’s death. All losses leave a mark, but this one cut especially deep, in large part because of his competence as a boater.

The greatest challenge for the community has been coming to terms with the harsh reality that the water doesn’t always care about expertise. “We like to think that we’re in control of things,” said Tobin, “but at the very best we only have some influence when it comes to whitewater.”

In the wake of his loss, kayakers close to Wood reviewed their habits on the water to double down on safety measures. “We’ve taken everything that we do and how we do it and put it through a new filter,” Tobin says.

They’ve mainly opted for a change in perspective rather than a change in practice, and many are more careful both about how they personally approach risks and how they represent the sport. “I definitely view the sport differently after Christian,” Stratton said, “though I think the change is not in my perceived danger, but in the danger exposed to others. I am more hesitant to do anything that I think someone else may see and think they can try.”

Some local boaters took time off from the sport over the past four years to give themselves room to grieve and reflect. But Tobin can’t think of a single person from Wood’s inner circle who has walked away entirely in the aftermath. The community has realized that awareness doesn’t necessarily translate to avoidance.

If the outcome had been different that day, Wood’s friends believe he wouldn’t have hesitated to get back out on the water.

“Christian would never want this tragedy to frighten anyone from pursuing their own path through the communities and sports he loved,” Tobin wrote in a letter to the Passages staff following Wood’s death. “He would never want anyone to miss out on these deep and formative experiences on account of him.”

Wood’s friends ultimately understand that the best way to honor his legacy is to pick it up right where he left off. Gill looks at one moment from his first day back at Passages after the accident as the sign he needed to do just that. He had a conversation with staff and campers about fear on the water, and he eventually found himself arm in arm with his coworkers, tears cropping up alongside the memories. “At some point, one of our kids said, ‘Well, should we go kayaking again?’ and we all kind of realized that there really was nothing else to do but exactly what would have made Christian happy.”