25 minute read

TEXTILES

WEAVING POSSIBILITIES

Government, industry bodies and business are fi nally working together to fi nd innovative ways to grow our textile and garment industry. By ANTHONY SHARPE

South Africa’s once-thriving textiles industry has fallen on hard times. Cheap (and illegal) imports, rising labour costs, the arrival of fast fashion giants and expensive tariffs are just some of the factors that saw more than 160 000 jobs lost in 15 years, according to industry researcher Simon Appel.

It’s an issue role players across the industry are attempting to remedy through a combination of innovation, partnerships and strategic repositioning. At the centre of these is the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTIC), which has been running the Clothing and Textiles Competitiveness Programme (CTCP) since 2009, and in 2019 launched the RetailClothing, Textile, Footwear & Leather Master Plan to guide the recovery and build new growth programmes.

“The textiles, leather and footwear industry is a very important manufacturing sector in South Africa, partly because it’s so

FAST FACT

labour intensive, in a country where level of the investment and the part of the we are trying to bring down value chain in which the company operates.” unemployment,” says Thandi At the core of the master plan is recognition

According to InvestSA’s Phele, acting deputy of the role of retailers in developing the 2020 textiles fact sheet, in director-general for industry, partly because they are the ones 2017 South Africa imported the DTIC’s Industrial that drive demand, but also to try and return more than R60-billion worth Competitiveness some of the production lines to South of clothing, textiles, footwear and Growth Division. Africa, onshore new products and rebuild and leather (with duties “It’s a sector that economies of scale for local manufacturers, of up to 40 per cent), predominantly employs work on the supply chain to improve representing between and creates multiple competitiveness, and assist local factories 60 and 70 per cent of those goods sold here. socioeconomic impacts and entrepreneurship opportunities for women.” in meeting retail demands.

INCENTIVISING INNOVATION

The CTCP comprises two incentive components, explains Phele – one to provide incentives to factories to invest in innovation and development, and the other to support cluster programmes. “We have focused on supporting companies in buying new machines, modernising production processes, continuous training and human development capacity, and doing research and development. The level Thandi Phele of incentive support differs depending on the

“FAST FASHION AND FASHION ON DEMAND REQUIRE QUICK RESPONSIVENESS. WE NEED TO REORIENT OUR FACTORIES SO THEY CAN SUPPLY WHAT RETAILERS ARE LOOKING FOR.” – THANDI PHELE, ACTING DEPUTY DIRECTOR-GENERAL, DTIC INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT DIVISION

DID YOU KNOW?

US company Cognex is developing a system called Cognex ViDi to automate textile inspection. The company claims the system can visually identify faults in weaving, braiding, knitting, fi nishing and printing, using deep learning trained on reference images to spot patterns and anomalies.

Source: Cognex

Marthie Raphael

“This has taught us that fast fashion and fashion on demand require quick responsiveness. We need to reorient our factories so they can supply what retailers and consumers are looking for,” says Phele. “The master plan methodology has heightened the need for collaboration between different parts of the supply chain, from yarn producer to textile manufacturer, to dyer, to clothing manufacturer and then to retail.”

Phele says the CTCP is currently under review to align it with the objectives of the master plan, to underpin and support the realisation of the commitments by the social partners, and to support the value chain during this diffi cult period.

REINDUSTRIALISING AMID A REVOLUTION

Investing in new technology is well and good, but these technologies require training as well as a different approach to work. Michael Lawrence, executive director of the National Clothing Retail Federation of South Africa (NCRF), gives the example of a modern textile mill, which requires R500-million to R5-billion in investment and occupies the area of several soccer fi elds. “Integrating fourth industrial revolution technologies into a factory like this requires retraining – your mechanic walks around with a laptop rather than a screwdriver, and is essentially a software analyst.”

That knowledge should be shared along the supply chain too. STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) skills are becoming increasingly important among retail planners and buyers, who need to understand the capabilities and challenges of the relevant technology, says Lawrence. “They need to understand preparation time and what economies of scale are appropriate for certain price points, they must have functional, realistic insights into the machines that make the items they sell.”

Lawrence says we may also need to take a look at the Competition Act. “The only way to justify such expensive technology is to make sure there is an agreement in uptake prices on the demand side, and that there is a certain amount of defi ned, reliable demand.” That will require retailers to participate in discussions, and, quite possibly, put money on the table to drive innovation.

Furthermore, to justify investments and become competitive the industry needs to take full advantage of the output capacities of modern machinery. “Our wage rates are competitive, but the problem lies when you move outside normal working hours,” explains Lawrence. “A good machine can operate 24/7, but under our current labour regime, you can only put workers at the machine for eight hours a day. That means you get only six or seven hours of productive value out of that machine per day. What we want is two, preferably three shifts a day, to bump up that machine’s productive hours to 22 per day, which makes investment in it far more viable.”

PIVOTING TO SURVIVE

Sometimes innovation involves pivoting around existing hardware and business models, as has been the experience of Pep Clothing (PepClo), a division of Pepkor, since the COVID-19 pandemic arrived on South African shores.

“People generally think innovation is about technology, but if you look at clothing manufacturing specifi cally, we’re not a capital-intensive industry,” says PepClo CEO Marthie Raphael, who adds that although sewing machinery has become somewhat more automated, it hasn’t changed much fundamentally over the years. “However, next to agriculture, we’re the most labour-intensive industry in South Africa and the world, the implication of which is that innovation comes from people.”

The pandemic proved a catalyst for such innovation, as PepClo management found itself trying to come up with a way to keep its 1 800 permanent staff busy during lockdown. They began by making cloth masks – consulting with the DTIC on specifi cations, designing prototypes, setting up the lines and getting workers back into the factory just over three weeks after lockdown began. “We didn’t innovate technologically – we had sewing machines and had to think of products that could be made using them – but we had to retrain staff completely to produce a new item, andin a relatively sterile environment too.”

From there the group expanded to making disposable isolation gowns for the Western Cape Department of Health. “We had to innovate across our entire supply chain,” says Raphael. “We entered the medical and nonwoven fi elds, which were foreign to us. We had to build up our supply chain for that, educate them, do testing on new fabrics, and realign our sewing lines and internal processes.”

TALENT MANAGEMENT

When people are your greatest asset, managing their skills and time effectively is essential, and here PepClo has found technology to be a boon, explains Raphael. “We just implemented biometrics for access control and attendance recording. We had an electronic time and attendance system in the past, but it was so archaic that we couldn’t draw details about our staff’s attendance and productivity.”

The new system gives greater visibility for people management per person and operation. “Absenteeism is always a challenge, and how you balance your skills in a manufacturing environment is important. Previously, we had a manual list of people’s skills, but if someone a manual list of people’s skills, but if someone was absent you had to page through it to fi nd a was absent you had to page through it to fi nd a replacement. Now we have that information at replacement. Now we have that information at our fi ngertips.” our fi ngertips.”

GOING GLOBAL

In 2019, US investor Mark Cuban and his partners invested in the manufacturing of a uniquely South African leather shoe, the Veldskoen, taking the shoe global.

Source: South Africa Fact Sheet 2020: Investing in South Africa’s Clothing, Textile, Footwear and Leather Sector (DTi and InvestSA)

THE RELEVANT TECHNOLOGY.” – MICHAEL LAWRENCE, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, NATIONAL CLOTHING RETAIL FEDERATION OF SOUTH AFRICA

KEEPING CLOTHING OUT OF LANDFILLS

How does textile recycling work and what sort of products can be made through this? BETH AMATO reports

Research by Dr Lorna Christie at the University of South Africa shows that in 2017 South Africans spent R180-billion on clothing and textiles, accounting for 18 per cent of all retail sales that year. But much of the clothing and textiles purchased is often poor quality and quickly discarded. Christie noted that discarded clothing is “hugely polluting” and that so-called fast fashion is similar to plastic in that clothes either don’t decompose or decompose very slowly. Furthermore, the chemicals and dyes used in clothing are harmful to delicate ecosystems if disposed of irresponsibly.

Textile production, even when natural fibres are used, is energy-intensive and comes at an environmental cost. Christie reveals that more than 10 000 litres of water go into the manufacturing of a single pair of jeans. “This is equivalent to the average drinking water for one person for five-and-a-half years,” she says.

Washing clothes releases 500 000 tonnes of microfibres into the oceans each year, says Christie – the equivalent of 50 billion plastic bottles.

FORWARD-THINKING FASHION

Our appetite for the latest fashions is not going to abate any time soon. And producing new garments, including those with better quality materials, takes a toll on the planet. But all is not lost, and it starts with consumers’ awareness and choice. Purchasing durable, ethically made garments is a first step. And South Africa is not short of innovative, forward-thinking, environmentally conscientious small and medium-sized textile enterprises.

Rhanda Clarke, owner of the Dress Shop in Durban, believes that clothing and textiles must be kept in use for as long as possible through reusing and recycling. “Our ethos is one of promoting a ‘circular fashion’ economy,” she says.

Clarke says that people are becoming more eco-conscious and second-hand clothing is becoming popular. However, the second-hand clothes market is still misunderstood. “When

Thrift shops play a pivotal role in the circular fashion economy.

you say ‘thrift store’, people think of a dusty shop with old stuff that nobody wants. We sell quality second-hand clothing and have an online shop too,” says Clarke, adding that the Dress Shop has customers buying and selling their second-hand clothes all over South Africa.

Christie notes that textile recycling is more of an informal process in South Africa. “We don’t yet have advanced textile recycling facilities and programmes here.”

A STITCH IN TIME

Melanie Brummer, owner of Dye and Print, says that only in extreme circumstances should clothing end up in a landfi ll. She notes that the mending of clothes is gaining popularity, especially overseas. “Clothing can last longer if people are ready to mend and reinvent it. Quality fabrics can last many years, especially if cared for mindfully – online communities share ideas about upcycling and extending the life of textiles.”

Formal textile recycling is complex, says Brummer. “Fibres need to be sorted to recycle them successfully. This is diffi cult to do, especially since one item of clothing is made from many fi bre sources.”

She agrees with Christie’s notion that textile recycling is more organic in South Africa. “We have such high rates of unemployment and homelessness. Unwanted garments very easily fi nd new homes if you just ask around in your

HAPPY IN HEMP

Abigél Sheridan of Chic Mamas do Care advocates for people to consider buying clothes made from hemp. Hemp is more durable than cotton, requires less water and space to grow, and has resistance to bacteria, lasting longer than many textile bres. Hemp doesn’t get distorted after being washed, gets softer with time and can grow in the same soil for 20 years without depleting nutrition.

network, and many South Africans donate such items.”

Brummer says that she usually starts by asking close friends and family if they’d like her clothes, then her work colleagues and then a charity shop. She says some shopping centres have bins with the word “Humana” on them, and clothes deposited there are distributed to those in need. Churches and animal shelters also sometimes accept clothes, she says.

RETHINKING OUR WARDROBES

Abigél Sheridan, owner of Chic Mamas do Care, says that we fundamentally have to rethink our relationship with clothing. “We like to say that the second-hand clothing we receive is ‘preloved’. Pre-loved clothing is not old clothing; our garments are in good condition, are dry-cleaned and resold. Those items that don’t make it to our rails are given to people in need, who either distribute items among themselves, upcycle them, or sell them.”

She says that all proceeds from clothes sold go to charity projects around South Africa. For example, Chic Mamas do Care has an upcycling project that uses old pieces of denim to create new products. People can deliver their items to stores in Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town and have them resold in aid of charity projects, to which over R8-million has been donated.

CASE STUDY: THE EQUATOR – THE BELT FACTORYTM A SUSTAINABLE JOURNEY

Areport by the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development, Repositioning the Future of the South African Clothing and Textile Industries (2020), posited: “Sustainability pressures within the [clothing and textiles] value chain will continue to grow in terms of environmental impact, ethical trade and localisation pressures.

“Production locations unable to verify their sustainability credentials may be increasingly locked out of leading global markets.” It’s clear that sustainability is no longer just a nice-to-have.

Equator – The Belt FactoryTM, is an example of an accessories company that has embraced the opportunity to produce high-quality belts, while ensuring this doesn’t negatively impact the environment. Leon Buhr, MD of the Durban-based company, says that it uses recycled material to make a resilient, nontoxic alternative to polyurethane.

The company’s factory was retro tted to include water tanks and improved waste management to prevent materials from ending up in a land ll or in water courses. Electricity and energy consumption were improved through double glazing on windows, motion sensor lighting, and LED lights. Now it takes less energy for the factory to manufacture a belt than it takes to make a cup of tea. “People assume that this is a very expensive process, but it’s simply not true – our energy costs are low, and our waste has been Leon drastically reduced,” Buhr says Buhr. Part of the company’s sustainability journey is its commitment to engaging with the United Nations Global Goals in an attempt to do its part to reach a more sustainable 2030. Buhr says that the company’s sustainability goals are divided into three manageable parts to be able to understand and change one aspect at a time: 1. Where is the belt made? 2. What is the belt made from? 3. How is it packaged and distributed?

So where to from here?

“Over the last few years, we have made great strides in developing plant-based materials that are vegan-friendly. These products age the same as leather and are incredibly durable. We will be continuing with this development with the hopes to make them accessible to the market,” says Buhr.

“Having achieved our green building certi cation in 2020, our 2021 focus will be on what our belts are made from, and how we can innovate our supply chain and materials usage. This interweaves with our dedication to two other 2021 goals that we, as a manufacturer, have: localisation and transparency.”

Production at Equator – The Belt FactoryTM .

DID YOU KNOW?

Equator – The Belt FactoryTM is the fi rst member of the local fashion supply industry to achieve a Five Star Green Star Certifi cation for Existing Building Performance from the Green Building Council of South Africa.

Manufacturing is about people

The faces behind Equator – The Belt FactoryTM

Manufacturing plays an important role in stimulating our economy. Behind every job is a multifaceted person integral to turning the wheels of industry. This is an important consideration when looking to buy clothes and products, and why it is so important to make an effort to support local.

Equator – The Belt FactoryTM is a leading Durban-based design house and manufacturer producing belts for some of South Africa’s major retailers and brands. It has also always been a proponent of people-fi rst manufacturing.

“People-fi rst means providing dignifi ed and productive work environments to all employees,” says director Leon Buhr. “It also means considering our environmental impact, and how we engage and listen to staff to create an inclusive and equitable company culture. In our world, soil is the lifeblood of our existence, in business people are the soil. From healthy soil, wonderful things can grow.”

THESE ARE THE PEOPLE OF MANUFACTURING

Meet some of the faces behind making your belts:

Amber Grant is Equator’s in-house trend forecaster and designer. “Trend forecasting is the starting point,” says Amber. “It’s about looking to the future and determining key trends, colours, silhouettes and materials that will inform the design of our products. I look at what is happening internationally and how we can make it relevant for our market.”

Vishal Ramdutt is Equator’s production fl oor supervisor. Vishal and his team are responsible for ensuring the craftsmanship and quality behind the manufacturers’ product, and aligning production processes with their aim to be more responsible, sustainable and circular in approach. “I love working with people and the challenge that supervising a big team brings,” says Vishal.

Nteboheng Mohare works in belt production on staining, ensuring the edge of the belt is properly stained and no residue is left on top of the belt. “Even though the work is sometimes hard, I apply love to what I’m doing so that I do it well. I’m proud of my job because through it I became a breadwinner,” says Nteboheng. Rajeev Matai is head of production excellence at Equator.

Teamwork is at the heart of our achievements

He also sits on multiple committees in the company, including the Employment Equity, Sustainability, and Celebrate Diversity committees. He is also the ultimate champion behind the company’s sustainability journey. Rajeev “When it comes to sustainability, Matai it has been amazing to take my Michael Peter learnings home with me. But I think the best part is when things start working and the hard work pays off. I feel so proud to see the staff at the factory doing their part and knowing that I had something to do with it.” Philisiwe Hlatshwayo has been responsible for ensuring that high-touch surfaces such as tables and light switches are sanitised multiple times a day since the start of the pandemic. This is in addition to her regular routine of ensuring all areas of Philisiwe Hlatshwayo the factory are cleaned each work day. “It has been diffi cult with COVID-19”, says Philisiwe. “But I work hard at my system and my time management and ensure that I do them well. I enjoy my job and take great pride in what I do.” Lungani Manqele is in charge of waste management. Part of what Lungani does daily is sorting through rejects, materials

Vishal Ramdutt off-cuts and raw materials waste products from the factory with the aim to sell or donate these products to small businesses and informal traders. “I see a lot of value in this process,” Lungani Manqele says Lungani. “We not only have less waste, but we also supply many people with useful materials, which makes them very happy.”

Nteboheng

Mohare Amber Grant

“PEOPLE-FIRST MEANS PROVIDING DIGNIFIED AND productive WORK ENVIRONMENTS TO ALL EMPLOYEES. IT ALSO MEANS CONSIDERING OUR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT, AND HOW WE ENGAGE AND LISTEN TO STAFF TO CREATE AN INCLUSIVE AND EQUITABLE

COMPANY CULTURE.” – LEON BUHR, DIRETOR, EQUATOR – THE BELT FACTORYTM

For more information:

031 702 1469 8 Pine Industrial Park, 16 Pineside Road, New Germany, 3610, KZN, South Africa https://equator.group https://thebeltshop.co.za

PATCHING UP THE CLOTHING AND TEXTILE INDUSTRY

THANDO PATO speaks to stakeholders from the clothing, textile, footwear and leather industry about their plans to help revive the local industry and create jobs

Key stakeholders in the clothing, textile, DID YOU KNOW? footwear and leather (CTFL) industry are The City of Cape Town in partnership with the Craft and Design Institute has committed to restoring South Africa’s launched the Cape Skills and Employment Accelerator project, focused on once-proud sector. The Retail-Clothing, creating employment opportunities for youth and women in Cape Town’s Textile, Footwear & Leather Master clothing and textile industry over the next three years. Plan, formulated by the sector, labour and the Source: Craft and Design Institute Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTIC) in 2019, aims among other things to ramp up by the sheer volume of undervalued “The IT infrastructure in our plants is showing us local production to boost and misdeclared imports of its what a massive difference we are making to local employment in the sector, products, such as yarns and fabrics, retailers by being nimble,” says Choice. with a target of creating 165 and the products of its customers, The group currently has 3 170 employees 000 jobs by 2030. such as domestic textiles and apparel. across its various factories and plans to grow the

Key challenges facing Illegal imports have displaced the local staff complement by 2 000 in the next year, with the industry include illegal supply chain.” an overall target of 5 000 over the next few years, imports, a lack of government imports, a lack of government Brink says what has also hastened explains Choice. “We intend to roll out support, and a skills shortage in the industry, says Brian support, and a skills shortage Graham Choice the decline is a severe shortage of managerial, operational and an expansion programme that includes taking over factories that are in trouble and absorbing Brink, executive director of technological skills in the industry. them into our value chain, allowing us to retrain the Textile Federation. “The “This hampers the necessary their staff.” textile industry has been severely impacted upgrading of productivity and technological He says that training, deploying modern advancements to meet the competition.” production equipment and processes, and an effective HR strategy are all key to the

PUSH AND PULL RELOOKING THE WAY BUSINESS IS DONE expansion programme. Part of the TFG

ON EMPLOYMENT Graham Choice, head of TFG Design Centre, strategy includes introducing a curriculum that

In 2016, StatsSA reported that the Manufacturing and Prestige Clothing, says is pitched at NQF level 2 and 3 for sewing,

CTFL sector had the biggest loss in that to successfully contribute to the master cutting and fi tting so as to standardise the employment in the manufacturing plan, TFG has taken a strategic multipronged skillsets required and upskill staff currently doing industry between 2005 and 2014, with approach in its operations. This includes those jobs. He adds that the industry needs more 91 000 jobs lost. In the third quarter of changing its production and manufacturing senior people on the shop fl oors. This is why 2020, the manufacturing sector (including model to compete with that of Chinese TFG is introducing a Production Management

CTFL) reported job losses. However, the importers, who need at least six months’ Academy, which offers an intensive two-year

DTIC recently announced to the Portfolio advance notice to produce fashion for each training programme including a modern

Committee on Trade and Industry that season for local retailers. approach to production management. investment to the value of R564-million from stakeholders such as Pepkor with

R30-million, TFG with R350-million, and Glodina with R184-million has already helped save 4 300 local jobs in the CTFL sector. “We intend to roll out an expansion programme that includes taking over factories that are in trouble and absorbing them into our value chain, allowing us to retrain their staff.” – GRAHAM CHOICE, HEAD OF TFG DESIGN

ENGAGED AND INFORMED

When it comes to employee health and safety during a pandemic, TFG has found that communication is key

Employee safety, welfare and morale have been more important than ever over the past year, with businesses working hard to support their staff through challenging times.

“The key to keeping all our employees engaged, informed and motivated has been constant communication via multiple channels,” says TFG group director Senta Morley.

A COVID-19 multifunctional task team was formed upfront, and regular meetings were held to ensure that all employees were aware of the different measures taken to ensure their safety.

TFG launched a COVID-19 portal for employees to access communication, policies Morley says employee safety comes fi rst, with COVID-19 health and safety training accessible through TFG’s intranet portal, the app and kiosks in manufacturing plants., as well as printed booklets for those not comfortable with digital training. “In addition, and documents in one secure our wholly owned Prestige Clothing factories in place, and HR-related concerns and Caledon and Maitland have an in-house radio questions could be addressed via a station – Radio Prestige – where education and dedicated app. information was constantly being shared. We “Especially during the early and also shared educational COVID-19 videos with most critical phases of the lockdown, employees through our extensive WhatsApp

Senta there were weekly updates sent out networks set up for ease of communication.” Morley by TFG’s CEO Anthony Thunström, TFG has partnered with INCON, its wellness both to address critical issues and to provider, to assist all employees with COVID-19 reassure employees,” says Morley. support. “This includes a 24/7 helpline

“We also ran a series of ‘Thankful Thursday’ which provides counselling and emotional campaigns during which we shared good news support during these challenging times,” stories to lift sentiments.” concludes Morley.

– SENTA MORLEY, GROUP DIRECTOR, TFG

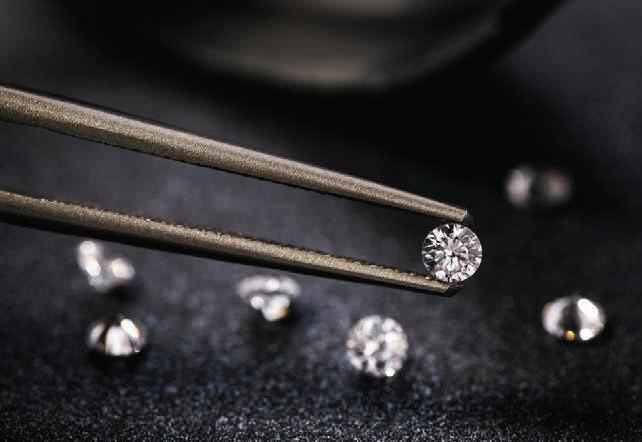

FROM MINE TO FINGER

American Swiss has partnered with Kwame Diamonds to introduce a diamond that’s a cut above the rest

If diamonds are indeed a girl’s best friend, then why aren’t there more female diamond cutters? That might’ve been the question on the lips of sisters Jo Mathole and Khomotso Ramodipa back in 2008 when they established their diamond-cutting business, Kwame Diamonds.

Fast forward a decade or so, and a different question was on the lips of American Swiss: how could they create a uniquely South African diamond, one that hadn’t travelled through many lands to be cut for their customers? “We were looking for a team who could mine, cut and manufacture diamonds locally,” explains American Swiss group director Shani Naidoo. “When we met Jo and Khomotso, there was an instant connection. It felt like meeting people with the same objectives.”

Naidoo says the Kwame Diamonds story resonated with them. “We learned they were mining in Alexander Bay. Those are alluvial diamonds – they are deposited into the alluvial plains where the Orange River meets the ocean and they have amazing clarity.”

The sisters said they could do a unique cut for American Swiss and the relationship began to grow, says Naidoo. “Most diamonds are cut with 58 facets, but we asked them to develop a unique cut. We ended up with 67 facets – and if you look at the diamond from below it looks like a ower, and from above, like a star. This is why we decided to name it the Ocean Flower diamond – now a registered American Swiss proprietary cut.”

FULL TRANSPARENCY

But the relationship has been about more than just creating a uniquely cut stone. “If you buy a diamond in South Africa today, it’s dif cult to get clarity on where it was mined,” says Naidoo. American Swiss follows the Kimberley Process, certifying their diamonds as “con ict-free”, but some customers want further clarity on provenance. These answers aren’t always easy to provide. “When Jo and Khomotso came onto the scene, they provided the answer,” says Naidoo. “They said they would mine and cut the diamonds for us, giving us transparency along the supply chain. In theory, a customer could come to us and ask for a

Shani particular diamond, then track Naidoo its progress from mine to nger in real-time.” American Swiss is launching the Ocean Flower with its annual diamond promotion in July. “For the customer who wants something unique, in its year of launch, we think the Ocean Flower will be extremely special.”

SHANI NAIDOO, GROUP DIRECTOR, AMERICAN SWISS