8 minute read

Pragmatism & Progress: Sister Missionary Service in the Twentieth Century

Pragmatism & Progress

Advertisement

By Andrea Radke-Moss

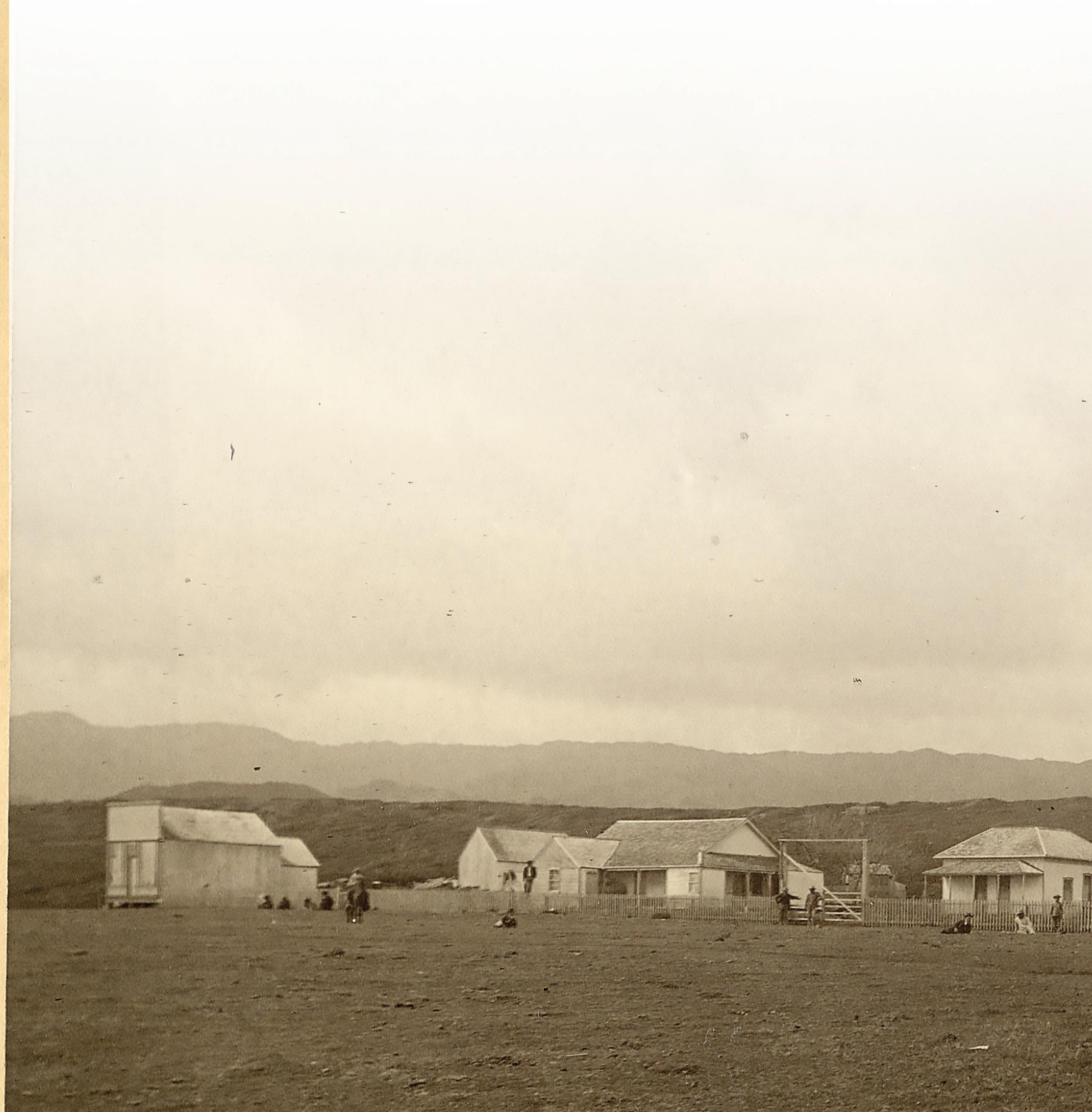

President Thomas S. Monson’s announcement in General Conference on Saturday, October 6, 2012, that young women can now serve missions at age 19 is no less than revolutionary. This move might seem like a pragmatic attempt to boost global missionary efforts. However, a brief historical overview of the last century’s changes for sister missionaries provides some useful context for how remarkable this policy really is. Nineteenth-century Mormon missionary service was almost exclusively male, with only small opportunities, here and there, for wives like Louisa Barnes Pratt and Lucy Woodruff Smith to serve as companions to their husbands. Estimates place the numbers of female “missionaries” at fewer than 200 during the entire 19th century.1 A major shift occurred in 1898, when the Church called the first full-time proselyting single female missionaries, Inez Knight and Jennie Brimhall. The Church needed female public representatives to counter persistent negative stereotypes about Mormon women, especially in the decade of the post-polygamy transition. Susa Young Gates recognized both the pragmatic and progressive virtues of missionary service for women:

“[ ] was felt that much prejudice could be allayed, that many false charges against the women of the Church could thus be refuted, while the girls themselves would receive quite as much in the way of development and inspiration as they could impart though their intelligence and devotion.” 2

By WW I, sister missionary numbers increased as males were called to military service, with the number of sisters peaking in 1918 at 38% of the total missionary force.3 During these early years, a sister’s age and length of service depended upon her circumstances, but the minimum age for sisters generally held at twenty-three. During World War II, when missions closed and elders were called home, sister missionaries picked up some of the slack. The year 1945 was “the only year . . . in which sisters accounted for a majority of missionaries set apart.”5 The post-War idealization of women’s traditional roles reached deep into Mormon culture as well, with renewed emphasis on early marriage. Church mission policy reflected this return to domesticity. In 1951, the minimum age for sisters was officially set at twenty-three, perhaps largely to encourage earlier marriages. President David O. McKay introduced this policy change in the following way: “It is surprising how eagerly the young women and some married women seek calls to go on missions. We commend them for it, but the responsibility of proclaiming the gospel of Jesus Christ rests upon the priesthood of the Church. It is quite possible now, in view of the present emergency, that we shall have to return to the standard age for young women, which is twentythree.”6 Jessie Embry has calculated that while there was a small increase in the percentage of sister missionaries during the Korean War, “yet the raw number of sister missionaries actually fell over the same period.”7 Another swing occurred in 1964, when the Church dropped the official age for sister missionaries back to 21, a change that proved crcuial when some wards were limited to only one elder per year during the Vietnam War. Overall, female numbers increased again for a time, but by the 1970s, cultural changes had given rise to anti-sister stereotypes like the “unmarriageable Old Maid,” especially as conservative gender expectations pushed back against the feminism and social changes of the 1960s and 1970s counterculture. The popular Mormon musical, Saturday’s Warrior (1973), reinforced notions that missions were male spaces and that women properly filled supportive roles as dutiful girlfriends waiting for their missionaries. A member-authored article in 1969 suggested, “One of the reasons why so few women are missionaries might be that their

first calling is to stay home and write to them.”8 Sisters on missions sometimes felt defensive. One sister wrote,

And this: “Is there any reason why a sister missionary can’t be just as effective as a Heber C. Kimball or a Wilford Woodruff? I may not have the Priesthood, but my call is just as real as theirs.”9

Winning over male missionaries remained a challenge. One sister remembered, “In every area that we went into, one of our jobs would be to convert the elders to the fact that lady missionaries had a place in the mission field.”10 And an elder admitted that “When I entered the mission field, I subscribed to the widely held notion that sister missionaries were a flaky lot who had been unable to find husbands and who could make little contribution to ‘real’ missionary work.”11 In 1971, the Church shortened the mission length for sisters to 18 months. Since then, Church leaders have maintained a unified position on sister missionary service, at once recognizing and complimenting those who serve while also reminding women of their first priority toward marriage and family. The two-year age difference between elders and sisters reinforced domestic expectations, keeping sisters at or below 20% of overall missionary numbers. In recent years, attitudes about sister missionaries have certainly shifted, with more young women serving because of a “first choice,” rather than as a “fall-back” plan. And in an interesting role reversal from an earlier time, many young men have actually “waited for” their sister missionaries after completing their own missions. Indeed, being a returned sister missionary is something of a badge of honor. And yet, problems have persisted on rare occasions, including the stereotyping of sister missionaries as somehow unmarriageable. Not so long ago, a friend of mine shared her mission plans with a ward member who responded, “Why would a pretty girl like you want to serve a mission?” Seen in the context of shifting historical policies regarding sister missionary service, the 2012 age change sends a remarkably affirming message to young LDS women. The sheer numbers of women serving will hopefully minimize double standards or extreme labels assigned to women, including the “binary extremes . . . [of] ‘good sisters’ or ‘problem sisters.’”13 Further, a lower age for women effectively separates missionary service from historical anxieties over the marriage-ability of young women. Even though women are still not required to serve, the message is clear: sisters are not an addendum or afterthought; they are essential to the missionary program, even irreplaceable. There’s also an implied message that “We trust you sisters to work alongside elders of your same age without worrying about whether you will be distractions or temptations to one another.” The age change puts missionary service for young women squarely on their road maps of major life milestones, even privileging “Mission” as a desirable step toward life preparation. Young women will have more opportunities for lessons about companionship, effective communication, conflict resolution, problem-solving, public speaking, more intense gospel study, doctrinal preparation, church governance, and leadership. As with previous historical changes in Latter-day Saint female missionary service, the 2012 age change has occasioned remarkable opportunities for young LDS women. As

they experience personal miracles and hone spiritual gifts through full-time missions, they will strengthen families in faith and Church activity for generations to come.

1 Calvin S. Kunz, “A History of Female Missionary Activity in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1898,” MA thesis, Brigham Young Univ. (1976). 2 Gates, quoted in Jessie L. Embry, “Oral History and Mormon Women Missionaries: The Stories Sound the Same,” Frontiers 19:3 (1998), 172. 3 Tally S. Payne, “‘Our Wise and Prudent Women’: TwentiethCentury Trends in Female Missionary Service,” in New Scholarship on Latter-day Saint Women in the Twentieth Century, ed. Carol Cornwall Madsen and Cherry B. Silver (2004), 128. 4 Payne 131. 5 Ibid.

6 McKay, quoted in Payne 131; Vella Neil Evans, “Woman’s Image in Authoritative Mormon Discourse: A Rhetorical Analysis,” Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Utah, (1985), 153–4. 7 Jessie L. Embry, “LDS Sister Missionaries: An Oral History Response, 1910–1970,” Journal of Mormon History 23 (Spring 1997), 115–6.

8 Patty Jackson, “Do You Qualify for the Heavy-Wait Award?” Improvement Era (May 1969), 56. 9 Mary Virginia Clark Fisher, “Journal 1975–77,” MS 16429 (microfi lm), Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. Entries for February 12 and 20, 1976. 10 Elaine C. Carter, “Oral History,” transcription of interview by Rebecca Vorimo, June 30, 1994, LDS Missionary Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Lee Library, Brigham Young Univ., 16. 11 Quoted in Embry 131. 12 Radke and Cropper-Rampton 144. 13 Mary Ann Shumway McFarland and Tania Rands Lyon, “‘Spiritual Enough to be Translated, But Too Heavy to Get Off the Ground’: Stereotypes and the Sister Missionary,” conference paper, New Scholarship on Latter-day Saint Women in the Twentieth Century, Provo, Utah, 20 Mar. 2004; copy in possession of the author; used by permission.

Over

22,000

sister missionaries were serving at the end of 2014.

1940 – today

With the outbreak of WORLD WAR II several missions were closed and many elders returned home.

— 1945 marked a time in Church history when there were more sister missionaries than elders.

— 1950: The fi rst standard ’plan’ was a set of six lessons that missionaries memorized word for word in the language of their respective missions, supplemented by fl annelboard pictures.

— 1964: THE AGE REQUIREMENT for sister missionaries changed from 23 to 21. — 1971: THE MISSION LENGTH for sisters dropped to 18 months.

During the mid-1900s departing missionaries were given a FAREWELL

TESTIMONIAL often followed by a dance. Programs were printed, fi nancial contributions were solicited, and refreshments were served.

— 2012, OCTOBER GENERAL

CONFERENCE: “I am pleased to announce that able, worthy young women who have the desire to serve may be recommended for missionary service beginning at age 19, instead of age 21.” —President Thomas S. Monson