9 minute read

The Watch

In the light of his vision he has found his freedom: his thoughts are peace, his words are peace and his work is peace. Dhammapada . are headed, but when he leads, the trail lit up only by the adventure in his eyes and the reflection from his glasses, I worry at every step that I will pitch forward into a pit and despair for centuries with the bone dust of Khmer builders.

We step more carefully through the darkness that has become cooler now that the sun is retreating from the Buddhist Bayon. ―Do you smell that?‖ he asks, and I do, a faint scent of incense, so common to Cambodia, but not common here within these old dead walls. Somewhere incense is burning and once he knows it, he must find it.

Advertisement

I imagine men and women gliding through these passageways, thinking of sacred text, of their next meal of rice and fowl and gingered vegetables, of staying out of trouble, of marrying into power and having babies to marry off into more power. I am thinking some of the same things. Of marriage. Of putting our decade together, our labor of love, into historical context, not just into history.

The incense smell is stronger now. Its floral layer rides a wave of musk that draws tears from my eyes. We become aware of a red glow. Ahead in a corridor, a bit higher, there is light. I expect it is a red beating heart, the heart of the king, still alive and preserved within Angkor Thom‘s walls. I want my own heart to be preserved, to stop moving around, to stop aching, to just sit and pulse. I want my mouth to look serene.

He leads me into a spherical cavern, what might have been the summit of the thirteenth-century Buddhist universe. In the center of the room, there is an old monk in yellow robes, nodding and swaying on his knees. While he, smiling, peers down at the monk, I peer upwards toward a tiny white dot of light at the top, a seemingly pin-sized hole that attracts and funnels the incense smoke now filling the little room. The white dot blinks several times. There are bats up there, flying back and forth across the hole, resettling on better perches, sensing the strangers who have just arrived.

He squats, looks up into my eyes. We turn to the monk who beckons us to sit down, no, kneel down, and we do. Next to the monk is a flaking golden Buddha covered in lotus flowers and bat droppings.

For the first time all day we put down our burdens, laying the cases and backpacks behind us. My knees are sweaty and itchy, but I am joyful that we are next to each other with no bags, and that neither of us is leading. I take his hand, hoping that mine feels both malleable and firm.

The monk chants, hovering around one note, close to the E below middle C, I think, just sharp enough to live between the E and the F, a precarious crack in music. The monk‘s voice is clear; he must be inhaling and exhaling in circles. The incense carries the song up through the white hole, up over Angkor, up into the heavens now dotted with stars. And there, in front of the once-radiant Buddha and the aged monk singing, we kneel together with nothing else to do or think about but the proximity of our thighs and shoulders.

The monk‘s voice stops abruptly as he leans forward. I think he is going to tip, to pass out, but he leans deep at the waist, bowing, his bald head kissing the floor in silence. When the monk returns to an upright kneel, he gazes at us with peace and completion.

We turn to each other. For a moment I believe we have been married within the bride city. We had the leg strength and the nerve. We just needed to be still.

Under the monk‘s gaze, he gets up first, gathers his gear, places riel notes in a tray at the foot of the Buddha, and quietly slips out of the room. I linger, breathing the incense and lotus, in and out. I look around. He is already gone. I find the way out on my own.

Suzanne Farrell Smith has essays published or forthcoming in The Writer’s Chronicle, Connotation Press, Muse & Stone, and Hawaii Women's Journal. She‘s finishing her first book, a hybrid of science and memoir that chronicles her attempts to excavate lost memory. She and King J found synchronization—they are happily married.

Flash Prize: $100

Kamil Dawson

By

Ron Orem

Ididn‘t really need a watch. I didn‘t need to know the exact time. The day started when the black of night gradually turned to grey, when forms emerged from the gloom. It ended when darkness returned, usually with a suddenness that is typical of the jungle, of places where there are no lights to disturb the blackness, where the canopy is so thick one cannot see the stars even on the clearest of nights.

During my turns at guard, the radio handset resting in my hand came softly to life every thirty minutes or so with a whispered call to provide a ―sit-rep,‖ or ―situation report,‖ of what was happening at my location. A barely audible ―sitrep negative‖ was all the answer needed. At the fourth call, two hours had passed; time to carefully touch the next soldier for his turn to sit quietly in the dark, his turn to count his heartbeats as a measure of the passing time.

While we slogged through the jungle thickets, time was measured by the counting of paces. Every few hundred meters, we stopped. This may sound like a short distance, a brief stroll to those used to walking on groomed trails or paved sidewalks, but in the tangle of vegetation which we carefully, silently, slid through, watching for any disturbance of pattern that could signal lethality, it was the hard work of imprisoned laborers. A stop was a chance to

Two things incline the heart to wonder, the starry sky above and the moral law within. Immanuel Kant

take a swallow of warm water; ease the shoulders from the bite of pack straps; smoke a cigarette slowly; look at the map; check our progress with the platoon sergeant and the lead squad leader; measure the distance to the next stopping point.

Midday meal times were measured by how long it took to open and eat a can of rations, for a fire team to make a short cloverleaf around the flank of the platoon, to dry one‘s feet, one foot at a time, to brush a fresh, light coat of oil along the metal parts of the rifle. Then it was time to move on, time to struggle up the next slope, and the one beyond that.

A few men wore watches. Metal bands were discouraged, as the glint of sunlight on them could be seen a good distance, or so it was said. The reality was that little could be seen at any distance, and barely any sunlight found its way down to us. Some men had the broad leather watchbands common to that era. Those rotted away rather quickly. Most watches didn‘t survive long in the jungle, the constant moisture finding its way into the workings, under the crystals, fogging them, stopping the works.

But I had my eye on a watch, a special watch. The company executive officer wore a military issue plastic watch called, of course, a Mickey Mouse watch. It had an olive drab nylon wristband, its housing was plastic, and it didn‘t reflect light. It was an impossible-to-get item, reserved for officers and those in the rear who could skim off supplies before they got to the field soldiers. I wanted one.

One steamy morning we sat by the air strip, waiting for the cargo plane that would carry us into Cambodia. The XO was there to do some administrative tidying before we went, and to see us off. He wore that watch. I badgered him for an hour, reminding him he had no need for it, being in the rear with the gear, the cold beer, clean sheets, radios with music playing loudly enough to hear, and clocks hanging on the walls. I could do a better job running my platoon with that watch; I would take good care of it. I promised to return it to him one day.

He relented, unbuckled the watch from his wrist and handed it to me. I noticed his arm, exposed below his rolledup sleeve, was tanned. There was sunlight back in the rear. An untanned patch where the watch had been marked its location on his arm.

I wore that watch for the rest of my tour. I set guard watches with it. I used it to decide when to stop the platoon for rest breaks and when to end moving for the day. It was dependable. It didn‘t fog up, and was light on my wrist. When I returned to the world it stayed with me, a constant reminder.

Then one day I met a soldier working at the local college in the administration office. He had no legs. He had lost them to a mine that had casually tossed his armored personnel carrier, and him, off the road he was patrolling. When he came to, much later, he was missing his legs, and his watch, which someone along the treatment path had wanted more. He remembered that watch, and told me he missed it a great deal.

Without hesitation, I unbuckled the watch, handed it to him. He thanked me, removed the silver bracelet watch he was wearing, put it on the desk, and carefully placed the worn, battered green plastic watch around his wrist. His eyes grew sad, but just for a moment, and then he remembered to smile. I didn‘t need the smile as much as he did. The watch was home.

Ron Orem, who served as an Infantry Rifle Platoon Leader in Vietnam, now lives in Owings Mills, MD, travels the country on his BMW motorcycle, practices ball room dance, and leads sweat lodges.

Flash Prize: $100

Ghost Dust

Connie Mygatt

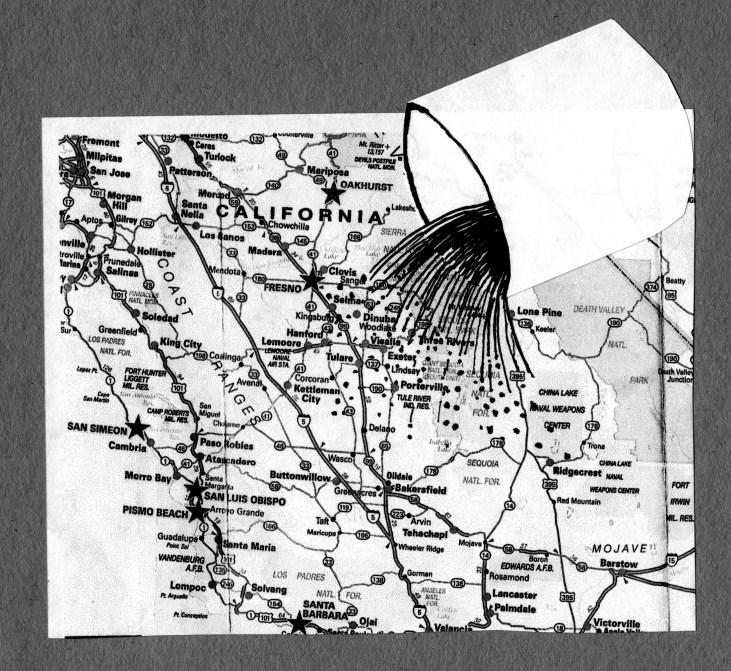

by Pat Pomerleau-Chavez

It is true, you cannot go home again. A conundrum: You think you left. You never leave, you cannot return. But there are milestones along the road. Some call them memories. I call them Ghost Dust. Fragrance of Indian Paint Brush; grains of alkaline soil between my fingers; a full mirage with palm trees; acres of poppies and lupines; oil stench. Ghost Dust blowing tumbleweeds from Buttonwillow. McKittrick, Maricopa. Ghost Dust blowing through the year of my birth. 1931. The Great Depression rolling on. I come back to California in 1955 to Ghost Dust blowing over the wreck at Blackwells Corner. Oil on the road. Oh, Jimmie Dean, Jimmie Dean! Come back now! We love you! Come back before it’s too late! Jimmie Dean… A recent trip to where I came from: Taft–Ford City. The lower San Joaquin Valley. The last trip. Desolate towns. But the desert itself not desolate. Not a manmade thing. Beauty lies beneath manmade ugliness. Grasshopperheaded oil wells have replaced the tall wooden derricks. Some so close together they drink from a common pool. The dregs.

Ford City, a shambles. Abandoned houses. Siding flaps in the wind. I glimpse Tom Joad slinking down an alley. Gaunt cheeks, hurt eyes. Steinbeck, on my father‘s porch,