8 minute read

and Ian Thomson

A GREAT PLAYER AND AN EXTRAORDINARY HUMAN BEING

“What a cricketer, what a man, what a life.” That was how The Guardian’s Matthew Engel concluded his appreciation of Ted Dexter, who died in August last year, aged 86. It seemed an appropriate way to sum up not only a great player but an extraordinary human being.

It seemed fitting that Dexter was born not only in Italy but in Milan, that country’s most fashionable city, with its glitzy catwalks, haute couture stores and the home of the majestic Duomo Cathedral and Leonardo da Vinci. So he was a little special from the off, and never stopped being so throughout his long life. He wrote a thought-provoking blog almost to the end and in 2020 compiled an entertaining and quick-selling autobiography, Ted Dexter 85 Not Out.

He was Edward by name and Edwardian in style for there was, in his debonair and charismatic play, more than a reminder of the golden age of cricket at the beginning of the 20th century. AC McLaren, you sense, would have approved of him. Like the classical and attacking McLaren, he dominated his crease from the moment he arrived and never looked in any trouble. Until he got out.

Yet he was, in so may ways, a modern and innovative cricketer and a true Renaissance man. In 1963 and 1964 Sussex won the first two Gillette Cups under his leadership because he was the first captain to understand that limited-overs cricket was essentially a defensive game. When he stopped playing he was the brains behind the first player rankings system, sponsored by Deloitte. When he became chairman of the England selectors he played a key role in setting up central contacts, four-day county cricket and England A matches.

He was also an outstanding golfer – “the best amateur player I’ve ever seen,” said Gary Player, with whom he once halved a match. When he was 85 he beat his age in a round at Sunnningdale. He played rugby to a high level and was an original newspaper columnist and TV commentator – when asked to cover England’s Ashes tour of Australia he flew there in his own light aircraft, Pommie’s Progress. He took his model wife, Susan with him, as well as his two children, The journey took five weeks.

He would have been an even greater sensation

in today’s celebrity culture, because apart from flying planes he drove fast cars and motorbikes. In 1964 he stood for Parliament against future Labour prime minister James Callaghan. He was the author of a number of books, including a novel, and ran his own PR company.

But it is as a fabulous batsman that he will be most fondly remembered. For me, there was not another player who created such a frisson of excited expectation as he strode to the crease. It was something the same with Viv Richards and Denis Compton. I first saw him in 1963, when he scored that thunderous 70 from 75 balls (very fast scoring at that time) to tame the West Indies fast bowling attack of Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith.

I watched it on TV – when a TV looked like a snowstorm paperweight inside a lump of walnut.

He was often criticised for playing too many vignettes, but this great attacking batsman had a Test average of 47.89. He also played two outstanding match-saving innings, 180 at Edgbaston in 1961 and 174 in eight hours at Old Trafford in 1964, both against Australia. How many of today’s England batsmen, distracted by the white ball game, have the temperament and technique to play innings such as these?

He retired in 1965 after running himself over with his own pale-blue Jaguar as he attempted to push it to a petrol station. But, to my delight, he made a brief comeback in 1968 because he was told he was need by England to play against Australia that year. At Hastings, three years after that retirement, he warmed up for his Test recall by scoring 203 against Kent, with Derek Underwood at his peak.

Tony Greig recalled: “Our 12th man was sent out from the ground to clear a runway of sorts so that Ted could land his private plane. When he strode into the dressing room, a strange smell accompanied him. It was his cricket case, unchanged after three years, and suffering severely from mould and dry rot.”

A week or two later Jack Arlidge, the respected local freelance, asked me to get a few quotes from Dexter concerning his England recall. I rushed up to the great man, pen and notepad ready. “Not today, sonny,” he said, pushing me gently away, He thought I was an autograph hunter! But I forgave him.

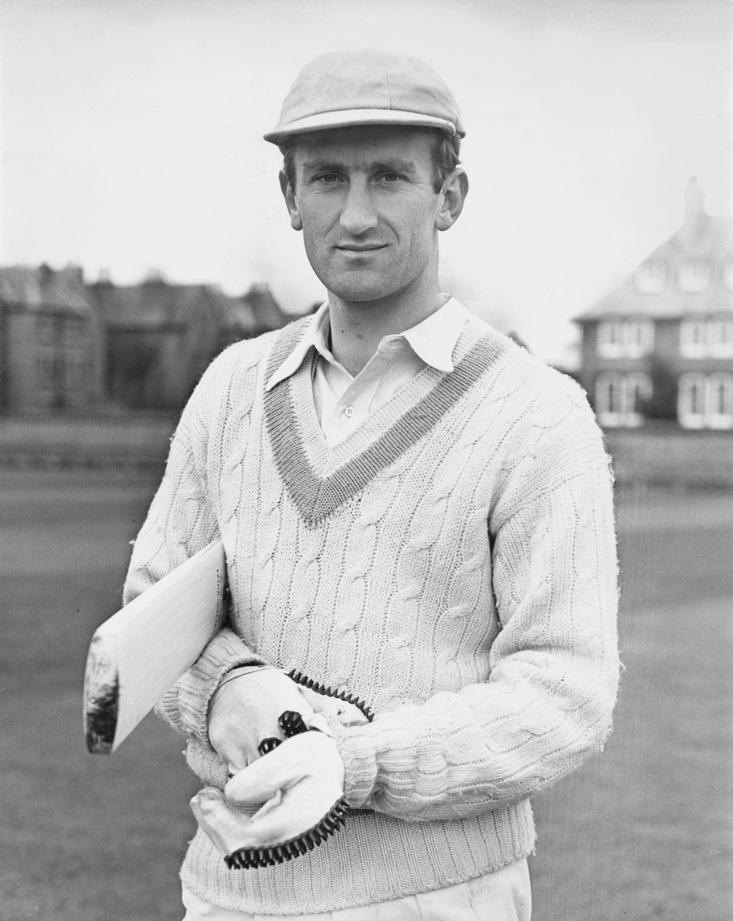

TED DEXTER GETS READY TO BAT AGAINST KENT AT HOVE IN 1964

SUSSEX SUPPORTERS KNEW HOW GOOD THOMMO WAS

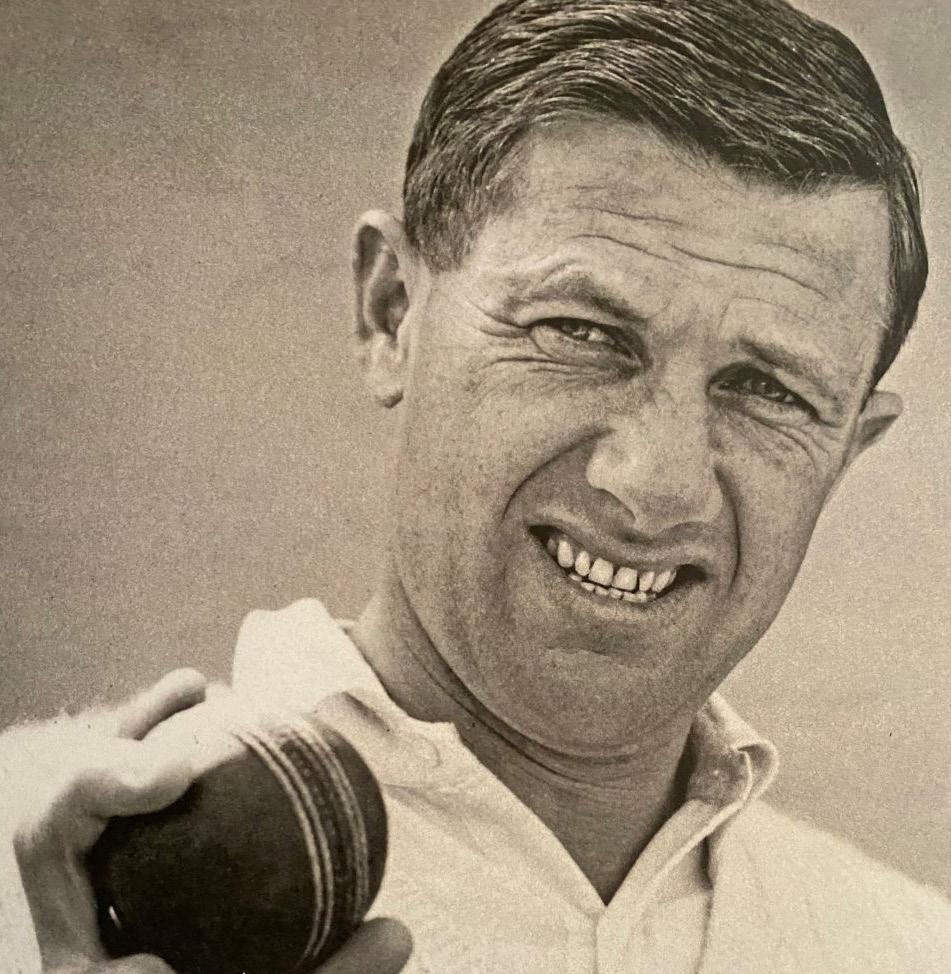

IAN WITH THE BALL HE TOOK TEN WARWICKSHIRE WICKETS WITH AT WORTHING IN 1964

Ian Thomson was the finest medium-fast bowler produced by Sussex since the great Maurice Tate. His shuffling, almost apologetic approach to the wicket disguised the dangers he presented to the unwary batsman.

He took 1,597 first-class wickets at the miserly average of 20.57 and claimed 100 wickets in a season on 12 successive occasions between 195364, two fewer than Tate. He bowled inswingers, an often deadly leg-cutter and achieved surprising bounce. At the Manor Ground in Worthing, in 1964, he took all ten wickets in Warwickshire’s first innings and finished with a match analysis of 15/75. He bowled 59.4 overs, and 34 of them were maidens. “But the highlight of my career was winning the second Gillette Cup in 1964,” he told me a few years ago. “We beat Warwickshire in the final and I was man of the match after picking up four wickets. Mike Smith was the Warwickshire captain and when he was selected to lead England in South Africa that winter he picked me for the trip because of how I’d bowled against Warwickshire. In those days you could often book a tour place with a good performance in the September cup final.”

Thomson died in August 2021, aged 92. Jim Parks, who succeeded him as England’s oldest surviving Test cricketer, said: “I’ve got so many fond memories of Thommo. We shared a room all the way through our careers. He was very accurate and very effective. He was unlucky not to play more often for England. He wasn’t quite quick enough to be an England regular but he was so successful on the county circuit, especially when there was something in the pitch for him. He was also a more than useful bat and had a great arm in the field.”

Sussex were fortunate not to lose such a fine player to Essex. Thomson was born in Walsall but his family moved to Ilford when he was a boy. He has a successful schoolboy career as an all-rounder and played for Essex Young Amateurs but, it was said, he failed to impress the very influential Trevor Bailey.

His cricket career took off when his family moved to Brighton in 1951 and he wrote to Sussex asking for a trial. That season, in ten 2nd XI matches, he batted in the middle order and scored 380 runs at 25.33. His bowling, though, disappointed and he only took four wickets at 74.25 each.

That changed in 1952 when he and Parks first played for Sussex. He immediately became an important member of the side and the following season – when Sussex, inspired by the captaincy of David Sheppard, finished second – he topped the county’s bowling averages with 101 wickets at 20.06 each. For the next decade he was the mainstay of the attack.

He thrived on pitches with a bit of green in them. There were three wickets in four balls against Gloucestershire in 1953 and against Kent in 1957. He had figures of 8/79 against Worcestershire in 1956 and 7/12 against Northants the following year, including four wickets in eight deliveries without conceding a run.

IAN, LEFT, OPENS THE EXHIBITION DEDICATED TO HIS TEN-FOR WITH CHRIS ADAMS AND ROB BODDIE AND JON FILBY, RIGHT, OF THE SUSSEX MUSEUM

He retired while still at the top of his game, at the end of the 1965 season. He returned to play a few matches in 1971 and 1972, playing his final game at the age of 43, before starting a teaching career. In later life he cared for his wife, Eileen. When she died in 2015 he became an enthusiastic participant in the old players’ reunions and in 2018 opened the Sussex Cricket Museum exhibition dedicated to his capture of ‘all ten’ against Warwickshire.

There were two professional disappointments. “We so nearly won the Championship in 1953 and would have done so if we had Mushtaq Ahmed in the team,” he told me. “It gave me great satisfaction to cheer the team on to their first title some 50 years later.”

His long-awaited international career proved to be an anti-climax. His five Tests were all played on that 1964-65 tour of South Africa, which brought him nine wickets at 63.11. He was better than that. But with other outstanding medium-pacers around, most notably Hampshire’s Derek Shackleton and Tom Cartwright of Warwickshire, he never won a home cap. Sussex supporters, though, knew exactly how good Ian Thomson was.