THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE culture | people | nature | taste | design

e define Swedish Lapland in a hundred ways or more. For the mountains, forests and wetlands, and for the major rivers flowing continuously into the archipelago of the Baltic sea. For the people who live here and for the broad, untouched expanses of nature. For the art, music and literature. For a cultural landscape and for wildlife.

Naturally, our everyday life defines us as people. The seasons, the distances and the climate up north have not only dictated a special way of life, but also a life in which nature is a major aspect, almost like a religion.

The destination Swedish Lapland is a common brand used by the northernmost municipalities in Sweden, making it Your Arctic Destination. For us, at Swedish Lapland Visitors Board, the quality of life in the region is more important than its boundaries. And what we are trying to describe is an Arctic soul. But what is that?

Indigenous people lived here long before any king moved the boundaries for his domain farther north. The king’s men called them Lapps, but they called themselves the Sámi and their homeland Sápmi; a borderless land that stretches across the Nordkalotten region, from northernmost Norway, over northern Sweden, into northern Finland, all the way to the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

Today we refer to this region as Arctic Europe. It is a part of the world that has become increasingly interesting for political powers and foreign investors. A place in love with the open and welcoming society, sometimes referred to as “swedishness”, but always on our own terms, under hail or mosquito swarms, snowstorms or sun blisters. Today this northern region is the most progressive in Europe.

Naturally, Swedish Lapland, is a vital part of the global fabric, that has been shaped since time immemorial. Via our neighbours – Finnish Lapland and northern Norway – we are the only part of Sweden to share national boundaries with two countries. And, somewhere at this intersection, there is something that we wish to define as a unique lifestyle.

We dry our meat in the spring, smoke our fish in the summer and boil our coffee over an open fire all year round. And we put ‘coffee cheese’ in our boiled coffee because we love the taste and the squeaky sound it makes between our teeth. Throughout history, amid the clatter of reindeer hooves and life in weathered log cabins, something very exciting has emerged. A destination, of course, but also a place to call home is evolving under northern lights or midnight sun. An everyday Arctic lifestyle deeply rooted in nature that we wish to share.

For us, Swedish Lapland is not really a place, but rather a way of life. And you are welcome to share our Arctic lifestyle.

2 OUR MANIFESTO

swedish lapland

SÁPMI

map

Swedish Lapland Sápmi

Swedish Lapland represents the Swedish part of the Arctic region, shared with seven other countries: USA (Alaska), Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Finland, Russia, Canada and Iceland.

How far north is Swedish Lapland actually? For example:

• Whistler in Canada has the same latitude as Frankfurt in Germany at 50° north.

• Hokkaido in Japan has the same latitude as Rome in Italy at 43° north.

61° anchorage , alaska 64° reykjavik , iceland 66°arcticcircle68°abisko

Photo: Linnea Lundkvist

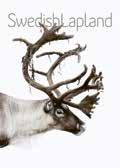

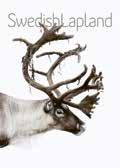

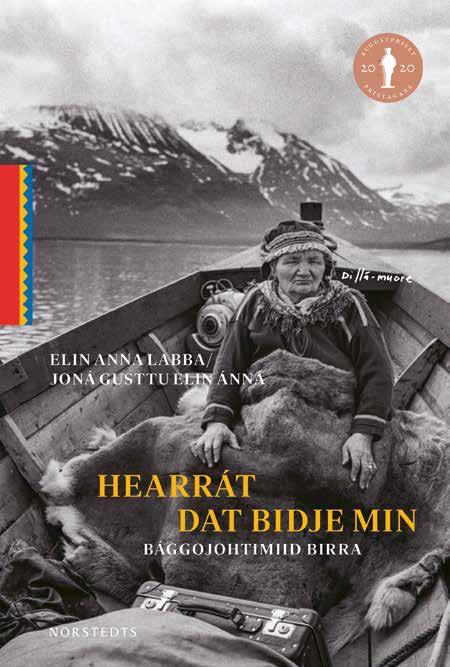

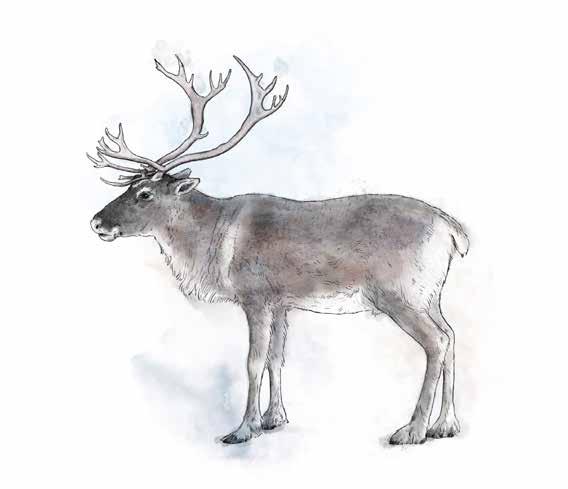

THE COVER

Reindeer are iconic to the Arctic. This magnificent bull was portrayed by award-winning photographer Andy Anderson at Nutti Sámi Siida in Jukkasjärvi, where you can learn all about reindeer and Sámi lifestyle. Read more about this amazing animal at page 50.

EDITOR’S NOTES

At the editorial office of this magazine we know that we are fortunate. Every day, we wake up in one of the best places in the world, to live and visit. And that because of all the hard-working entrepreneurs and enthusiasts that make this place ticking. Thanks!

We would also like to acknowledge that all our work take place on the traditional grounds of the following reindeer husbandry associations, the indigenous Sámi people, of: Könkämä, Lainiovuoma, Saarivuoma, Talma, Vittangi, Muonio, Gabna, Laevas, Girjas, Baste earru, Tärendö, Sattajärvi, Korju, Unna Tjerusj, Sirges, Jåhkågaska tjiellde, Slakka, Gällivare, Ängeså, Pirttijärvi, Kalix, Liehittäja, Tuorpon, Luokta-Mavas, Semisjaur-Njarg, Ståkke, Udtja, Svaipa, Maskaur, Västra Kikkejaur, Östra Kikkejaur, Gran, Ran, Mausjaur och Malå. Giitu!

This edition wouldn’t be possible without the contribution from some of the industry’s finest: Andy Anderson, Linnea Lundkvist, Anna Nygren, Per Lundström, Magnus Winbjörk, Carl-Johan Utsi, Hans-Olof Utsi, Asaf Kliger, Mattias Fredriksson, Tobias Hägg, Konsta Punkka, Eeva Mäkinen, Frauke Hameister, Marco Grassi, Andres Larrota, Johan Ylitalo, Anders Lindberg, Adam Klingeteg, Mattias Hargin, Viveka Österman, Josefin Wiklund, Thomas Ekström, Lucas Nilsson, Sven Burman, Peter Rosén, Daniel Holmgren, David Björkén for your amazing work with the cameras. Lisa Wallin for your beautiful illustrations. Mark Wilcox, Mia Linder and Jesper Sandström for spot-on translations. Finally, if we hadn’t been so busy having fun, we would have finished this edition last year – or even the year before – so we won’t promise when the next issue will appear. But somehow it will. Until then, stay safe and see you soon.

THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

The Arctic Lifestyle Magazine is a standalone publication, published by Swedish Lapland Visitors Board – the regional representative of the tourism industry in Sweden’s Arctic destination, Swedish Lapland. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author, or persons interviewed and do not necessarily reflect the view of the editors.

EDITORIAL Swedish Lapland Visitors Board: Anna Lindblom, Art Director. Josefine Ås and Håkan Stenlund, Writers. Contact us at redaktionen@swedishlapland.com

PRINT Lule Grafiska, Luleå.

SWEDISH LAPLAND® is a registered trademark used as destination brand of Sweden’s northernmost destination. The region includes the municipalities of Arjeplog, Arvidsjaur, Boden, Gällivare, Haparanda, Jokkmokk, Kalix, Kiruna, Luleå, Pajala, Piteå, Skellefteå, Sorsele, Älvsbyn Överkalix and Övertorneå.

4 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE R C T I C C I R C L E

C

THE ATLANTI

CONTENTS

89 62 98 72

culture people nature | taste design

THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

Photos: Asaf Kliger, Carl-Johan Utsi, Per Lundström, Konsta Punkka, David Björkén

Illustration: Lisa Wallin |

5 CONTENTS V I N D E LÄ LVEN LAINIO RIVE R Icehotel Arctic Stor f FINL A N D e4 PITE RIVE R L ULE RIVER R Å N E RIVER K A L I X R I V E R TORNE RI V E R LAKE TOR N E T R Ä S K A R C H I P E L A G O SWEDEN SKELLEFTERIVER NORWAY B A Y OF B O T HNIA VINDEL RIVER KÖNKÄMÄÄ RIVER M U O N I O R I V ER KIRUNA GÄLLIVARE ÖVERKALIX ÖVERTORNEÅ PAJALA KALIX BODEN ARVIDSJAUR ÄLVSBYN HAPARANDA LULEÅ JOKKMOKK ARJEPLOG PITEÅ SKELLEFTEÅ SORSELE 12 40 32

21 51

IT’S TIME TO

celebrate

Every day in life is a reason to celebrate, but some days are even designated holidays in the calendar. We have listed a few favourites that tell a bit of our story.

6 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE CELEBRATIONS

Photo: Anna Nygren

Lucia

Every year on December 13, Sweden wakes up to the sound of angelic voices in the winter cold. The northernmost part of the country is no exception. The Lucia celebration is widespread and something everyone looks forward to. Perhaps it is because we get to light candles, listen to the hymns, and eat buns made with saffron, which makes everything a bit extra special. Why else would we so eagerly celebrate a Catholic saint? Lucia of Syracuse became a saint because she provided food and assistance to Christians hiding in the catacombs of Rome. The crown of candles she wears is purely practical – to be able to carry food and supplies with both her hands. In times past, according to the Julian calendar, December 13 was the shortest day of the year. In many ways, this is when you feel like the year is turning.

facts: A Lucia celebration can be found in any church or school on December 13.

Christmas Eve

Christmas Eve, December 24, might be the biggest holiday of them all for Swedes. The kids are off school, and everyone is enjoying sweets, food, and Christmas gifts. The main Christmas celebrations have already been preceded by a kind of overindulgence known as Christmas smorgasbord. All through December, restaurants serve traditional Christmas buffets, and in Sweden everyone relishes it. Christmas food in the destination Swedish Lapland is rich in game and fish. There is no getting away from elk roasts, reindeer tongue and cured Arctic char. Not even if you actively try. Jellied meat and Christmas ham are other central items. And don’t worry – there are lots of vegetarian options.

facts: A traditional Christmas buffet can be savoured at many restaurants and hotels throughout December, but be sure to book in advance!

New years eve – do it twice!

New Year’s Eve has its own, specific traditions. Promises are made – and hopefully not broken on the same day. If you love toasting with bubbles and experiencing New Year fireworks, Tornedalen is the place to go. In Finland, on the other side of the river, the clock strikes midnight an hour earlier. If you are quick about it, you can toast, make promises, and watch fireworks twice this evening. First in Finland, then in Sweden.

facts: Celebrate New Year’s twice at the twin cities Haparanda in Sweden and Tornio (Finland), with two different time zones! At Victoria square in Haparanda people from near and far first cheer for the Finnish new year and one hour later the Swedish.

7 CELEBRATIONS

1

2

3

Photo: Anna Nygren

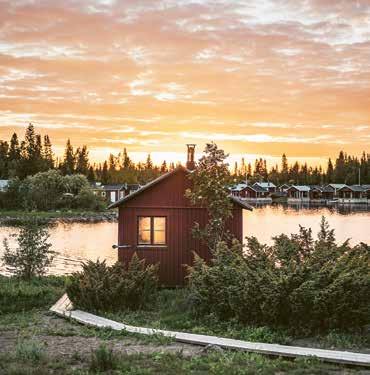

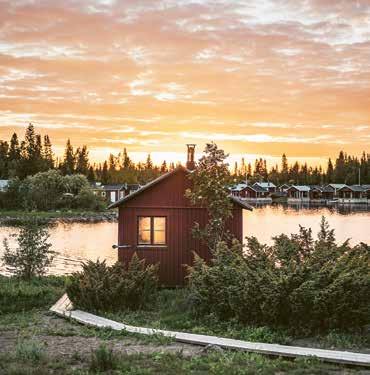

Brändön Lodge

Illustration: Lisa Wallin

Sápmi celebrates

February 6 is celebrated as the Sámi national day, commemorating the first Sámi congress that was held on that day in Tromsø in Norway 1917. The land of Sápmi extends through Sweden, Finland, Norway and Russia. On this day the national anthem Sámi soga lávlla is sung, and you can also hear the unofficial national jojk Sámiid eatnan duoddariid , by Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, all over Sápmi. The Sámi are the indigenous people of northern Europe, and one of Sweden’s five national minorities.

Jokkmokks marknad

For almost 420 years, on the first week of February, the Jokkmokk market has been a unique part of the Sápmi experience. People from all corners of the world meet for this special occasion, and foremost all relatives and friends from the geographically dispersed indigenous Sámi. Ask anyone in Jokkmokk and they will tell you that there is a before and an after this unbroken tradition. It is the real beginning and end of the year. The market showcases the best Sápmi has to offer in terms of culture and design. You do not want to miss the art exhibition at Sámij åhpadusguovdásj, the handicraft exhibition at Ájtte, the inauguration, the meat soup at Akerlunds and the Sámi Duodji exhibition, and more.

facts: The Jokkmokk winter market is inaugurated the first Wednesday of February each year an goes on for another three days in the town of Jokkmokk. jokkmokksmarknad.se

8 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE CELEBRATIONS

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Photo: Carl-Johan Utsi

4

Easter

Easter is celebrated in the north, of course. But when the rest of Europe is harvesting asparagus and going to mass, we go to the mountains and dig out a ‘solgrop’ in the snow. This ‘sun pit’ is a word as well as a phenomenon, as embedded in Arctic culture as fatwood and coarse-ground coffee. This is the best of times. The sun is warm again, and the days are longer than the nights.

facts: The sun is getting stronger this time of the year – don’t forget your sunscreen!

Fat Tuesday

Fasting is something we are not very good at. But the day before Ash Wednesday of the Christian tradition, all Swedes are chomping at the bit, feasting away on Fat Tuesday. The Swedish bun ‘semla’, the epitome of a prelent pastry, is found on every coffee table and every local newspaper crowns the best semla of the year.

facts: A semla is a delicious cardamom bun with a marzipan type filling, lots of whipped cream and dusted with powdered sugar.

June 6

We have a national holiday in Sweden too. They say it is celebrated because Gustav Vasa took to the throne on June 6 in 1523, but the new constitution adopted by King Charles XIII on the same date in 1809 may also have played a part. The day which used to be known as the Swedish Flag Day, became a national holiday in 1983 and a bank holiday in 2005. As you might have gathered, there is not a lot of fuss surrounding the national holiday – people just appreciate having a day off in the beginning of summer.

facts: Buy a picnic and go out into nature to enjoy a good moment amongst friends.

9 CELEBRATIONS

Photo: Per Lundström

Photo: Sofiia Popovych / Adobe Stock

5 6

7

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

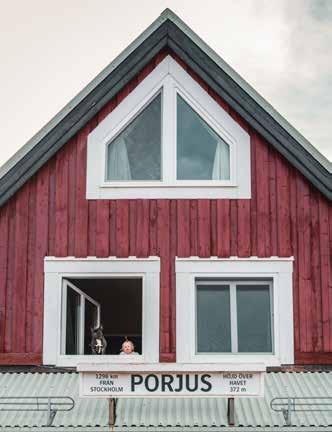

Huuva Hideaway

Midsummer

Perhaps we exaggerated when we said Christmas Eve was the most important holiday in Sweden. Midsummer Eve is just as important. Midsummer is the weekend when every Swede escapes to the countryside, to a little red cottage in a peaceful forest, or an island in the archipelago. The fact that this happens to be when the year takes yet another turn and it starts getting darker again is something we forget in the middle of schnapps, pickled herring, and some

dancing. What we still fail to understand is why a song like Små grodorna , The small frogs, became so important? Borrowed from the French – originally about onions – an ironic song about the French in the UK ended up as a family song in Sweden to be sung dancing around a maypole.

facts: Midsummer eve is always celebrated on the Friday in June that is closest to summer solstice.

10 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE CELEBRATIONS 8

Photo: Anna Nygren

The Day of the Tornedalians

Tornedalians, the inhabitants of Tornedalen, celebrate their national day on July 15. It is all about the bottomless longing for home, longing for roots, your place, and your family. It is celebrated it in July, because that’s the most beautiful time of the year. Meänflaku , meaning our flag, is hoisted, all for a place with its own unique culture. Even though it is a melting pot of two countries, several cultures and languages it come together as one. Tornedalians are one of Sweden’s five national minorities.

Fermented herring

There are two kinds of people in the north: those who eat Surströmming and those who don’t. To some, this fermented fish is more than disgusting. To others, it is the very essence of umami. Its history can be traced back to the 16th century and the Bothnian Bay, but the art of storing food by fermenting is much older than that, all around the world. First the herring is put in concentrated brine for a couple of days, to extract the blood from the fish. The fish is then moved to a less concentrated brine, to be fermented, for six to eight months before served.

facts: On the third Thursday in August, a characteristic, easily recognisable smell permeates the north. Local producers in Swedish Lapland are Storön, Kallax and Bockön.

The Crayfish Premiere

The Crayfish Premiere used to have a set date, August 7, but since a few years back it is up to local fish conservation areas to set the rules. At some point in the beginning of August, is the general guideline. The earlier prohibition was mostly in place to get cray fishing under control, so it would not be a drunken party the entire summer long. Article 9 of the Fisheries Act stated: “Crayfish are not to be caught during the months of June and July.”

facts: Crayfish parties are celebrated all over Sweden with funny hats, songs and a fair amount of schnapps.

11 CELEBRATIONS

Photo: BD Fisk

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

9 11 10

Photo: Magnus Winbjörk

The genius OF THE PLACE

12 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE PEOPLE

Photo: Asaf Kliger

Tjåsa Gusfors and Ulrika Tallving have a long-time relationship with Jukkasjärvi and Icehotel, creating art sculptures and fairylike rooms in the ephemeral material of ice.

For those who are blind to the experiences close to home, it can be difficult to assign a value to a nearby place that has intrinsic beauty, quality and taste. We asked some of the world’s foremost creatives in food, design, art and architecture to explain their relationship with Sweden’s arctic destination, Swedish Lapland.

artists tjåsa gusfors and Ulrika Tallving pause from building a suite at Icehotel No. 33. Outside, it’s -20 degrees Celsius, a light westerly wind is blowing and early traces of the Northern Lights begin to fill the sky. But inside the suite it’s a mere minus four and, for Tjåsa and Ulrika, returning from their break, it’s like coming indoors.

“Yes, for me, this is like coming home,” says Tjåsa, laughing.

For more than 20 years Tjåsa has created rooms, suites and art at Icehotel. She speaks of her first meeting with the place; she was here with a theatre group, visiting Icehotel just to see an exhibition. She says that it was as if the ice was speaking to her. She knew she must return. The following year she built her first room. Since then, she has returned again and again. Artist Ulrika Tallving now lives in The Hague. Ulrika normally creates artwork that doesn’t melt, often sculpting in stone. She built her first suite at Icehotel as early as 2007. Working in ice, letting art emerge from a natural material that will transform itself over the season and eventually melt, is very special.

“But that’s what I like most about Icehotel in Jukkasjärvi. You literally ‘dig where you stand’. And next year, we’ll do it again.”

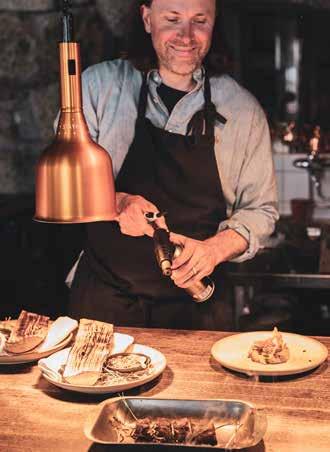

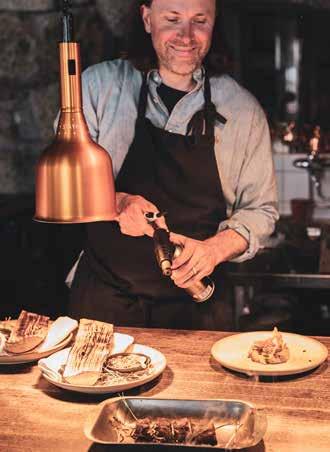

Guide Michelin chef Niklas Ekstedt’s first encounter with Riksgränsen was on a snowboard, years ago. Back then, he barely cooked at all. And, well, food was whatever it took to keep him snowboarding. 25 years

13 PEOPLE

later, standing in a full-blown snowstorm, he is preparing one of his signature dishes for aprés ski, oysters flambadou. Not exactly Swedish Lapland, if not for the weather, of course. Niklas Ekstedt smiles. He’s pleased. But you probably guessed as much.

“Many of Sweden’s classic ingredients are to be found here in the north. Ingredients that we are proud of, also in the south. Löjrom and reindeer, moose and cloudberries and all those sorts of things. But for me personally, when I come up here, it’s the snow and snowboarding I love the most. So, you don’t need to ask me how good the food and ingredients are. Ask me how good the powder was today. ”Then he laughs and serves another oyster.

a few months later, at the closure of the summer season, outside Harads, stands another Guide Michelin chef, Nicolai Tram, from Knystaforsen in the southern county of Halland. Here, under the flaming Northern Lights, he is also serving up a flambadou dish. But, instead of beef tallow and oysters, Nicolai lets melted moose fat dribble over a grilled fillet of reindeer. The flavour is sensational.

“We’re like bears,” says Nicolai, continuing, “We really just go out into the forest and gorge on everything we can find.”

Nicolai Tram was one of eight Guide Michelin chefs guesting the event Stars du Nord, which took place in the woods outside Harads, not far from Treehotel and Arctic Bath. The idea behind Stars du Nord is to assemble some of the very best Nordic chefs for a cook-along beyond the ordinary, and the real stars are the ingredients.

“Sweden’s far north seemed like the obvious location for our second Stars du Nord,” explains founder Caroline Thörnholm. “The region is central to the New Nordic cuisine. Not only is this where the chefs gather and prepare the ingredients, it also has a lot to do with the techniques they use to prepare them. Cooking over an open fire, smoking, brining and pickling are also very much a part of the Nordic context.”

Many northerners have a freezer filled with berries, fish and meat – whether it be moose, reindeer or free-range lamb – yet they fail to comprehend what a bounty this is. They tend to see it as work; picking, butchering, sorting and packaging. It’s a never-ending

job that follows the seasons. Like Sisyphus, rolling his boulder up the hill for all eternity, the northerners resign themselves to the fact that nature’s bounty simply must be harvested and the freezer must be filled.

kent lindvall probably knew there was a fine forest in Harads before he built his Treehotel. Nowadays, Kent finds it hard to understand what good a forest is unless you can live among the treetops. Yngve Bergqvist certainly knew you could sleep in a snow cave without freezing to death, but that was hardly his reason for building Icehotel.

After doing stints at two prestigious eateries, Noma and Oaxen, it became quite obvious that Piteå chef Johan Eriksson understood a thing or two about the quality of food; however, that he would miss outsmarting wary trout and living the simple life in the north, only he could know. And that’s why he opted for a fine-dining bistro in Piteå and opened Centrum Krog, instead of pursuing an international career.

Failing to see the wonders around you, in the place you call home, is one thing. Feeling homesick is quite the opposite. And homesickness is a powerful force.

14 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE PEOPLE

As much as Michelin star chef Niklas Ekstedt loves cooking, he’s an avid snowboarder and Riksgränsen is one of his favourite playgrounds.

The story of Moses, who must return home at all cost, parting the sea on his way; or Homer’s hardships on his journey back to his beloved Penelope, after the war, are myths that speak tellingly of what homesickness can mean. Sometimes, one simply must return home again, even if building a restaurant, a hotel or an art gallery has to be part of the equation.

As poet and clergyman Alexander Pope wrote, to Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, in his Epistle IV:

To build, to plant, whatever you intend, To rear the column, or the arch to bend, To swell the terrace, or to sink the grot; In all, let Nature never be forgot. But treat the goddess like a modest fair, Nor overdress, nor leave her wholly bare; Let not each beauty ev’rywhere be spied, Where half the skill is decently to hide. He gains all points, who pleasingly confounds, Surprises, varies, and conceals the bounds. Consult the genius of the place in all.

15 PEOPLE

“We’re like bears, we really just go out into the forest and gorge on everything we can find.”

Danish chef Nicolai Tram, who runs a Michelinstarred restaurant in southern Sweden, visited up north to cook a feast with fellow star chefs for the gastronomic Stars du Nord event long to be remembered. On local ingrediencies, over open fire in the woods of Swedish Lapland.

Johan Eriksson

Stars du Nord

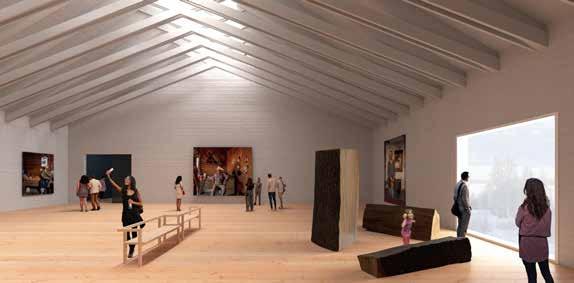

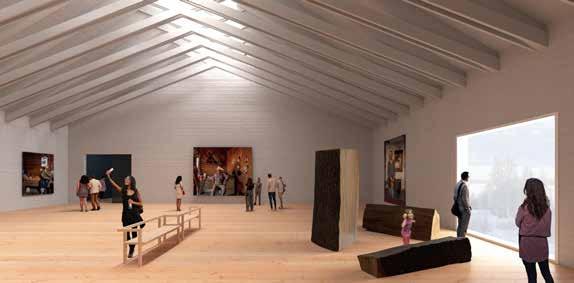

Arthotel Tornedalen like an Italian

incredible art collection.

a unique cultural institution with galleries for the finest art in the world as well

16 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE PEOPLE

“We need an art gallery in the north. Not only should we who live in the north also have access to art, but we should also be able to exhibit all of the fantastic art that we have here but might be a bit neglected.”

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Illustration: Oopeaa, art by Esko Männikkö

Konsthall Tornedalen will be

as a farm with local produce.

Gunhild Stensmyr runs

Albergho Diffuso, with an

many verses of Alexander Pope’s epistle have become famous, but the line “consult the genius of the place in all” stands out. Every place has its beauty, its intrinsic quality, its genius. Actually, it’s not so much about sustainability or preservation; it really has to do with letting the character of the place, its own true nature, come to the core. When Gunhild Stensmyr moved home to Risudden, in Tornedalen, it was with that feeling in mind. She wanted to bring some life back to the village with her Arthotel project, which can be likened to an Italian Albergho Diffuso. But then, the idea to create Konsthallen just fell into her lap.

“When I stand down here on the meadow, looking out over the Torne River across to Finland, I feel the same sort of sensation as I do when standing outside Louisiana, in Denmark, gazing over the Öresund Strait at Sweden. We need an art gallery in the north. Not only should we who live in the north also have access to art, but we should also be able to exhibit all of the fantastic art that we have here but might be a bit neglected. Why are Nils Nilsson Skum’s paintings hanging in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, or in Göteborgs konstmuseum, but not in a Konsthall in the place where he actually worked?”

israeli asaf kliger is a photographer and artist with an uncanny ability to enable the ice at Icehotel to speak to us through his images. The first time he landed in Kiruna and made his way from the aircraft to the arrivals hall he thought he would freeze to death, although the walk was a mere 25 metres. Now he loves the cold and light of the hotel, which this season as well has been built near the shore of the Torne River.

“With my photo art I want to give the world a bit more ‘wow’. That’s my style; more colour and more life in the images.”

Asaf’s career began with studies at the art academy in Jerusalem before he found his niche in travel and sports photography. While on a trip in Asia he met Josefin, who worked at Icehotel, and he decided to tag along. When asked about his first impression

of Icehotel, he is quick to respond, “It was cold.”

But after the initial shock, Asaf felt as if he was in a fairytale world. Meeting Icehotel was the best thing that had happened in his career. He runs galleries in Lund and Jukkasjärvi, but his images are exhibited all over the world. You’ll see them at Arlanda, on your way to the F gates in Terminal 5, or even on one of this year’s Swedish postage stamps.

“The whole idea behind Icehotel, the fact that it is reborn each year, makes it a wild playground for artists. Interacting with others who set no boundaries, even in snow and ice, has helped me enormously.”

17 PEOPLE

Photo: Asaf Kliger

Photographer Asaf Kliger has a rare eye for capturing the magic and details of the constantly changing ice art at Icehotel. In 2022 one of his photos from Icehotel was reproduced on the national postage stamps.

niehku mountain villa has been described by American journalist Leslie Anthony as the world’s best heli-ski lodge. But for alpine guide and hotel owner Johan Jossi Lindblom, the thought that such a place could ever exist never occurred when he was slogging it out as a ski patrol at the nearby resort Riksgränsen. It took several years abroad, and a few clients and investors, who remarked, “You don’t realize what you have here.” Niehku is the North Sámi word for dream. Of course, Jossi had dreamt of building something special, of giving something back to the place and the environment that had in so many ways shaped him, but he had no idea that it would become one of the world’s coolest ski-resort hotels. Erik Nissen Johansen, designer and owner of design agency Stylt Trampoli, understood this well when he and his colleagues decided to enter Niehku in UNESCO’s Prix Versailles, a sort of Oscars for interior design architects.

“What makes this project special is that its point of departure is in a human need, something that drives a particular group of visitors – those who come here to ski or hike. That has enabled the creation of a five-star product. Something we in Scandinavia have very few of.

For many, the meaning of the term ‘luxury’ has changed radically over the past 30 years. Instead of collecting Rolex watches and Ferraris, we gather poetic experiences that we can recollect and share around the dinner table. It’s beautiful.”

Erik Nissen Johansen is sitting by the fireplace, savouring a pinot noir. He and his friends at Stylt

Trampoli have won UNESCO’s Prix Versailles twice. They are the only team to have done so. And the interior of Niekhu Mountain Villa was one of their winning entries.

“The entire building has been built solely to meet the needs of quality consious outdoor-leisure enthusiasts. At the same time, it can escape no one’s notice that the heritage of Ofotenbanan, the railway line, has been carefully preserved. The instant you step through the door you feel an immediate sense of calm and contentment. I hadn’t been here in three years but, upon entering, the smiles on the faces of the staff and the welcoming sound of a crackling fire seemed to share a common DNA.”

18 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

PEOPLE

At the border between Sweden and Norway, Niehku Mountain Villa combines a stunning nature experience with high-end living and fine dining.

bjarke ingels has been called a genius, and justifiably so. Born in Copenhagen in 1974, he began university studies in architecture because he hoped it would make him a better cartoonist, which had always been his dream career. But architecture grabbed hold of him and he furthered his studies in Barcelona, at Técnica Superior de Arquitectura. After working in, among other firms, OMA in Rotterdam and PLOT, the latter of which he co-founded, he started Bjarke Ingels Group in 2005. BIG would become a major success. The firm now has offices in Copenhagen, New York and Barcelona. The Biosphere room at Treehotel was

the first project to be realized by his Barcelona office. From concept, to sketch to a unique hotel room surronded by 350 birdhouses amid the treetops.

“I am pleased by how we managed to achieve the spherical effect, despite the fact that the actual room is a cube; all of the birdhouses on the exterior create the impression that the interior is a sphere. And we really have achieved a harmony between interior and exterior. In principal, that’s what architecture is all about.”

Four years after starting BIG, Bjarke Ingels wrote his ‘yes is more’ manifesto. When asked if it is a reflection of his own personality, he explains that it has more to do with an attitude. It is important that we embrace the bigger context. Saying yes for your own gain is easy; but saying yes for the betterment of society, the ‘more’ in the manifesto, is more demanding. As Bjarke sees it, architecture has largely become stuck in two parallel ruts. On the one hand; avant-garde, with deranged, radical, oppositional architecture, which can at best be described as an oddity; on the other hand, traditional functionalism, which produces nothing more than what is expected – a rather boring box.

“These two streams have dominated architecture, but for us at BIG, the interesting thing has been to see what happens when the two meet and interact. We’re drawn into the no man’s land where they should overlap.”

Bjarke leans back in an armchair with a cup of coffee. A little bird flies up behind him and lands on one of the nesting boxes. It’s as if it has come to check the neighbourhood, to see who has moved into the biggest of the birdhouses today.

“Oh, look at that little bird.”

Danish architect Bjarke Ingels enjoys his creation, Biosphere, the eighth and latest tree room at Treehotel, a remarkable room perched among treetops in the woods of Harads.

19 PEOPLE

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Acne + Kero = True. A sustainable affair

World famous Swedish fashion brand Acne Studios teamed up with Kero, the northernmost Swedish shoe maker, for a unique collaboration on a modern yet sustainable take on the Sámi-style ‘beak’ shoes “näbbstövlar”. Seeking roots in local heritage, Jonny Johansson, creative director at Acne Studios, was looking for the language of clothing that evolved in the nomadic communities – how a style evolves with its own logic.

facts: Kero, a Swedish heritage brand based in Sattajärvi in Swedish Lapland, is known for its unique craftsmanship. Sustainability and local produce has always been key. As co-owner Emma Kero puts it: “At Kero, we have always been sustainable, ever since 1929. Nowadays we just need to tell it as well”. www.kero.se

www.acnestudios.com

SWEDISH LAPLAND IS THE TALK OF THE TOWN

Bastard Burgers

From Luleå to New York with Swedish burgers: Bastard Burgers celebrate their one-year anniversary in the Bronx. Really good smash burgers, beer from the Bronx Brewery and a small part of Sweden – this is what you get at Bronx Brewery East Village & Bastard Burgers, in New York.

facts: When in Swedish Lapland you can visit Bastard Burgers in Boden, Luleå, Piteå and Skelleftå. In New York you find the restaurant at East Village, 64 2nd Ave. www.bastardburgers.com

130 years anniversary

The first Lovikka mitten was knitted in 1892 by Erika Aittamaa. The story goes that the customer was not happy at first with the thick wool yarn that stiffened in the cold. But once Erika had washed the mittens and brushed the yarn again, the mittens were a success and a classic was born.

tips: Nowadays you can buy Lovikka mittens in most souvenir shops throughout the region.

20 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

Photo: Ted Logart

Photo: Bastard Burgers

On food

A SEASONAL ADVENTURE

21 TASTE

Photo: Per Lundström

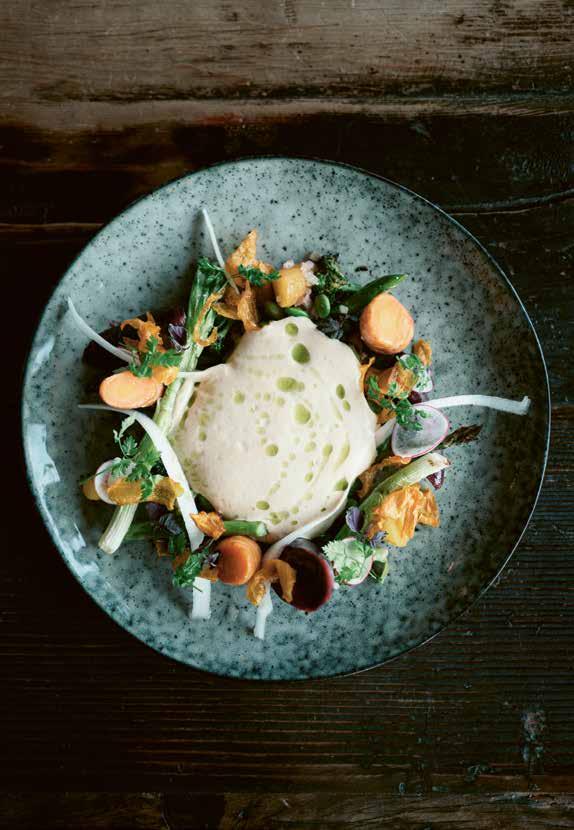

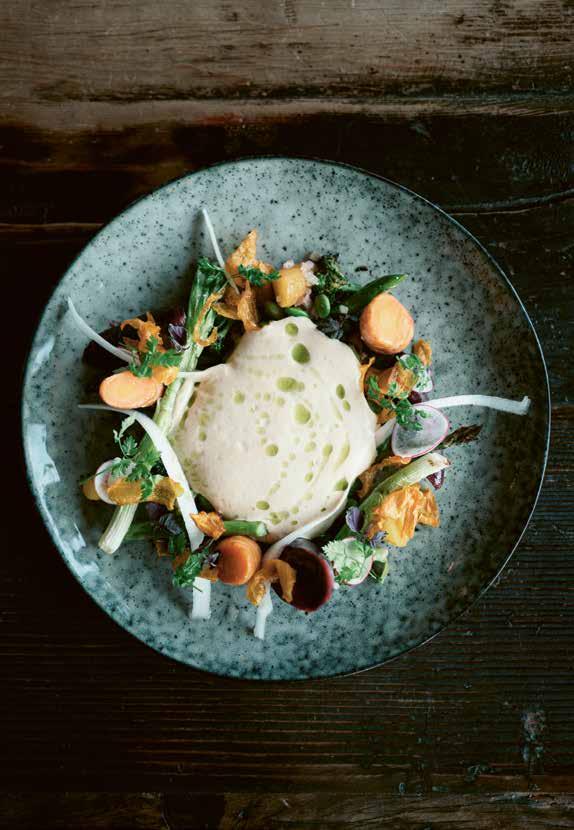

The seasonality of Arctic cuisine has created a unique food culture. In line with other parts of the green transition – where technological innovations are improving the future – sustainable cultivation methods are emerging in the north. From superberries and game to free-range cattle, during blizzards as well as warm summer nights.

seasons are important. Patience Gray writes in her now classic cookbook Honey from a Weed that “Good cooking is the result of a balance struck between frugality and liberality... born out in communities where the supply of food is conditioned by the seasons.”

What happens when you lose touch with the seasons is that you lose touch with life itself. Enjoying an unlimited supply of goods, from every corner of the world, at the supermarket is not natural. Autumn’s underground storehouse, on the other hand, filled with potatoes, turnips, carrots, and pickled and canned goods is part of something bigger. It is no coincidence that the people of the books would slaughter a spring lamb for Easter as a symbol of resurrection, of life returning, and fresh food once again being part of everyday life after the hardships of winter. Something just as natural as the Sámi tradition of sacrificing a white

reindeer to the godess Beaivi at Midsummer, ensuring that darkness would not prevail and the midnight sun would return the coming year. It is all part of the circle of life. Nothing comes in abundance except for intense periods – in the middle of the season, in autumn, during harvest time, when everything is gathered and stored in barns. It might seem surprising that so many households in the north have four freezers in the basement – one for meat, one for fish, one for berries and mushrooms and then one for discounted goods that will come in handy when there is something to celebrate – but this is actually part of everyday life. Hold on, did we mention the freezer for baked goods?

tasty food is eaten twice. First at the table, then in your memory. At Centrum Krog in Piteå, you eat a perfect Surf and Turf, perhaps not a classic Arctic dish

22 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

Traditionally grilled whitefish at the Kukkola rapids.

but still heavenly, that will awaken memories and make you dream of returning. When Jón Óskar Arnason at Bryggargatan in Skellefteå serves an elk-heart carpaccio from the animal he shot himself a few days earlier, it is also a memorable dinner you would like to relive time and time again.

A stop at Princess Bakery in Sorsele; where you buy laugenbrot sandwiches, just because the Swiss bakery by route E45 will take you to another place; is also an everyday occurrence these days.

When you find out that the man from Öland at Niehku Mountain Villa in Riksgränsen, Ragnar Martinsson, is serving elk sausages, you just get in the car and drive. Spending a few hours in the car is nothing when it comes to good sausages! It is also difficult to imagine a summer without netted whitefish at the Kukkola rapids, served fresh at the restaurant, 50 metres from where it was caught.

It is very easy to fall in love with vendace roe, but it might be an even clearer sign of the season when Simon Laiti once again starts serving fried vendace with mashed almond potatoes in September, at his restaurant Hemmagastronomi down by the northern harbour in Luleå.

finding ingredients from the north of Sweden in starred restaurants in the south of Sweden is a given, but the chefs we have mentioned have decided to move to – or back to – the ingredients they like working with. The Arctic part of Sweden features locally produced and wild ingredients Of course the destination is famous for its game and local fish, but also for free-range animals. This, however, does not mean that Europe’s most progressive destination is blind to other trends. Bistron in Luleå is a green oasis, at the Christmas smorgasbord at Brändön you find more and more vegan dishes, and Miss Voon in Skellefteå serves reindeer as sashimi – but you also get tuna and scallops. The new Nordic cuisine is celebrated for components that are smoked, pickled, salted, and freshly prepared over an open fire. Even if that is the traditional way in an Arctic context, the cuisine has always changed in line with how the world changes. Johan Eriksson at Centrum Krog says, when asked:

“Locally produced is our base. We get more or less all our meat from Nyhléns Hugosons in Norrbotten. But I love making good food, that’s why I became a chef, so taking ideas from elsewhere and adapting them to your own conditions is something natural.”

23 TASTE

Bistron in Luleå.

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

24 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

“Swedish Lapland has become Scandinavia’s most interesting dining destination.” condé nast traveler

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

When Johan makes his umami-rich XO sauce he skips the dried seafood and uses dried reindeer as the main ingredient instead. Something traditional from the Asian cuisine suddenly becomes Arctic. This was picked up on by American food writer Lane Nieset when she visited Piteå, and she asked a bashful chef for the recipe.

a few months later both the sauce and the destination were celebrated in Condé Nast Traveler. Lane Nieset’s headline “Swedish Lapland has become Scandinavia’s most interesting dining destination” sums up a food spree through the destination ending at Eva Gunnare’s place in Jokkmokk. Eva has become a household name over the years when it comes to foraging. She moved from Stockholm to Kvikkjokk some 25 years ago, which was where she first encountered traditional Sámi cuisine. A few years later her curiosity inspired her to look for the more forgotten Arctic cuisine. What herbs, plants and berries did the Sámi and settlers depend on? Today in Eva’s home, during a 22-course spread called Njálgge, you will be presented with alpine bistort, wood sorrel, dandelion buds, and angelica. You will drink mulled wine made from meadowsweet and cordial made from willowherb. The stem from willowherb is even served as a kind of tasty asparagus to complement the freshly slaughtered reindeer. The superberries are present, of course: lingonberry, blueberry, cloudberry, bilberry and hagberry in various forms.

the concept superberries was a hot topic some years ago. In the north, there is nothing strange about superberries. Studies have shown that both lingonberries and sea buckthorn berries help keep your weight in check. Blueberries, given their blue colour from the antioxidant anthocyanin, are credited with all kinds of good qualities – among them improved vision. Even without dissecting these berries and plants into smaller parts, we can state something very important: they

are very dependent on sunlight! In an arctic climate the growth period is short, and therefore extremely intense. The world’s northernmost mustard farmer, Per Pesula in Kukkola, might explain it best as he states:

“In summer, thanks to the midnight sun we have three months of growth during two calendar months. It’s bound to do something to the plants.”

In Norsjö outside Skellefteå, Rålund produces a wine from lingonberries and blueberries that has been well received, and in Öjebyn they make Svart, a bubbly made from black currants. We will get back to that.

rural development specialist Jenny Bucht in Bertnäs outside Piteå used to work for the Norrbotten County Board, coordinating the region’s food strategy. These days Jenny is both a sheep farmer and a consultant focusing on sustainability issues. She continues where Per Pesula left off:

“Thanks to our midnight light we have a very intense growth period, that brings out the best in the produce. Anyone who remembers photosynthesis, from their biology classes, knows that it is the sun that is driving the process. What happens during this growth period is that plants, grass, trees, berries and more are filled with a lot of energy during a short timeframe.”

Then she sums up: “Well, in short you could say that we have the best grass in the world and that’s why we produce the world’s best fodder, which naturally would lead to the world’s best meat.”

Jenny Bucht concludes that the northernmost region has not always been that good at understanding or communicating the unique, sustainable environment and its effect on food quality. Look at wild animals and freely grazing reindeer, how they spend summer and autumn eating and then starve in winter. This means the reindeer recycles its fat during the course of a year. In turn, that gives you a meat that’s been minimally affected by the environment. Jenny’s lambs, by the way, make an appearance every now and then at Johan’s restaurant Centrum Krog.

25 TASTE

Lingonberries

Photo: Per Lundström

in recent years, fire has started to play a more prominent role in the kitchen. No, we are not referring to the constant smell of barbecues filling camp sites and neighbourhoods as soon as summer approaches. Instead, fire has become part of the identity for famous Michelin-star restaurants and your local pizza place.

In the north, cooking over an open fire is something completely normal. If you take a walk in the forest, you make a fire and boil some coffee. If not, almost no one would count it as having been outside properly. Even in the middle of town, houses will often have a fireplace or barbecue hut outside to experience outdoor life without even leaving home. Fire is central to the dream of a good life in the north – for cooking, or for a sauna. These days it is part of the current trend at Michelin-star restaurants featuring the new Nordic cuisine. And during the ambulating food festival Stars du Nord, celebrated under the northern lights outside Storklinten in autumn 2022, nine of the best Nordic chefs showed how to make good food using fire, no electricity, and no running water. An amazing experience in every way.

hushållningssällskapet, The Rural Economy and Agricultural Society, runs an experimental farm in Öjebyn outside Piteå where research is carried out. In cooperation with SLU, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 400 different varieties of turnip rape have been cultivated to see which variety likes it best here in the arctic climate. But even more interesting is the trial using pheromones to combat pests. Mikael Kivijärvi, former CEO of the society and currently project manager for its innovative and land-based fish farms, says:

“Hushållningssällskapet has tried using various forms of biodynamic pest control,

26 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

“Fire is central to the dream of a good life in the north – for cooking, or for a sauna.”

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

even coating black currant plantations with turnip rape oil, but this project where pheromones are used among the berries has shown exciting results”.

The organic black currants from Öjebyn are actually worth another mention. They are used to make a sparkling wine from black currents according to the ‘méthode traditionelle’, the same way champagne and cava (among others) is made, which requires a lot of labour and precision. But the result is, according to the wine expert at Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet, a “dry and refreshing wine... with notes of iron, raspberry and tart berries”. Just perfect for the Christmas smorgasbord, according to the same expert.

From blackcurrents that become bubbly and turnip rape that could turn into farm-produced oil, we move on to Michael’s core activity: fish farming.

“Everything suggests that there will be land-based fish farming in the future. Simply because you can regulate the process in a different manner. With land-based farming you can control animal health, the spread of diseases, the water environment, escapees and so on. You can also use the water for irrigation, so-called aquaponics, or use the residue after water treatment as a base for feed or fertilizer.”

at the old military site AF1 in Boden, home to Boden’s Army Air Battalion until the beginning of the 21st century, there is a kind of winter garden. The 300-square-metre building is heated by residue heat from a data center where they mine cryptocurrency using blockchain technology.

“This is just a test facility. The idea is having a much larger greenhouse,” says Håkan Nordin, business developer at Boden municipality and continues:

“It wasn’t profitable before to use the residue heat from the server farm for district heating. The temperature of 40 degrees Celsius just wasn’t enough. But this, using it for a greenhouse, means it’s warm enough”.

In Boden they experiment with what will be, or could be, grown. The idea is to try to grow mango, banana, passion fruit and more, to see how it goes.

“The idea is simply to try to grow everything here that Sweden is importing at the moment, to see what works. It’s a way of improving our degree of self-sufficiency without having to forgo what we’re used to eating these days.”

If everything works out well at the old military base they will continue and build a 3,000-square-metre installation that will also work as an aquaponic farm. As mentioned, a kind of farm where nutrient-rich water from land-based fish farms is circulating around vegetables being grown. The greenhouse is cutting-edge not only because it uses residual heat, the AI-based growing technique that continuously checks the plants is also expected to reduce cultivation losses by up to 30%.

this future scenario gets even more exciting when considering the investments made in Boden. H2 Green Steel’s new hydrogen-producing steel plant is Sweden’s largest industrial project: a 600-hectare area – the largest development plan in Sweden – with 70 hectares set aside for further development of greenhouses and cultivation. But Boden sees this cultivation as more than just a sustainability project in environmental terms – which it is, of course, as Dutch tomatoes transported by lorry to north Sweden in winter are grown in greenhouses heated by foreign gas and then driven 2,000 kilometres north using

27 TASTE

Håkan Nordin

Svart

diesel. It is as important that this large-scale project that will bring both social and financial sustainability: creating entry-level jobs and increased self-sufficiency. Perhaps this creates a discrepancy in our story, that started with the advantages of the midnight sun and the seasonality that has created an Arctic way of life and constitutes the base of the new Nordic cuisine, to talking about large-scale greenhouses of the future. But on the other hand: development does not cease on the outskirts of the modern world. Rather, it could be driven from here.

in piteå, at the parking area by Västra kajen, a number of food artisans gather on a Wednesday night in February. This is a kind of farmers’ market known as Reko-ring, and people from near and far come to shop for locally produced products. Anders Skum and his Fjällvilt from Ammarnäs is here. The award-winning food artisan says that during the pandemic this Reko-ring saved his finances. Similar setups to Rekoring are available in many other locations now. This evening the farm Strömnäsgården from near Harads is present too, with chickens and eggs from Norrbotten’s

first foraging chickens, as well as outdoor pigs from Järvtjärn and Vuollerim’s Mathantverk.

Reko-ring is a concept that has grown using social media and current awareness of what constitutes good food. In Burträsk village, the farmers have started their own farmers’ market where members take turns during opening hours. You can find everything there, from cutlets from outdoor pigs to rabbit fillets and Kielbasa sausages made using original Polish recipes. In Boden there is another farmer’s market.

Åsa Lindman and Magnus Eriksson who run Strömnäsgården say the reason why they began to keep chickens and later cattle was simply that they wanted to know what they were eating. And conclude:

“But we also love living in the countryside”.

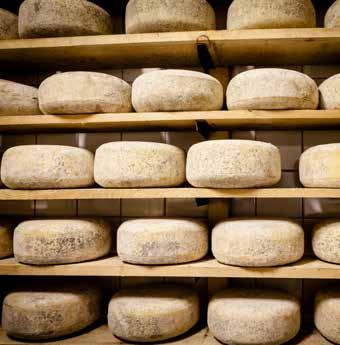

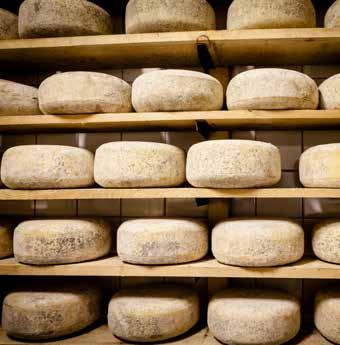

Less than an hour’s drive from Strömnäsgården, up the Lule River towards Jokkmokk, is Vuollerims Mathantverk. They produce an award-winning cheese using milk from mountain cows.

This region, with the world’s best grass, or fodder, has many products to offer with clean water and an air of world-class quality. A lot of it thanks to the summer season under the midnight sun.

28 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

Photo: Carl-Johan Utsi

Photo: Carl-Johan Utsi

29 TASTE

Photo: Bryggargatan

Bryggargatan

Kalixlöjrom

Sweden’s first food product to receive a protected designation of origin was Kalixlöjrom, Kalix vendace roe. Other examples of famous products around the world with designation of origin could be Bayonne ham, Champagne, and Stilton cheese. The vendace, a small fish in the salmon family, provides us with the gold from the sea. Every female produces some 3–5 grams of roe. The vendace fishing starts on September 20 and lasts for about five weeks. The fishing has been MSC-certified since 2015 and is regulated by the Norrbotten Coastal Fishermen’s Association in cooperation with the Agency for Marine and Water Management. Kalix Löjrom is a delicacy, and the fish itself is just as tasty.

Cheese

Västerbotten cheese, ’Västerbottensost’, is Sweden’s most famous cheese. The dairy company Norrmejerier produces this delicacy at a small dairy in Burträsk. The characteristic flavour is said to be the result of dairywoman Ulrika Eleonora Lindström forgetting her chores – that is, keeping the curd at a consistent temperature –because she was busy having an affair. We are not sure what happened to that love story, but we do know that we love Västerbottensost.

Mustard

Sweden’s – and probably the world’s – northernmost mustard farmer is found in Kukkola, at Pesula Lantbruk. The rich soil along the Torne River and the abundance of light during the midnight sun period make mustard seeds flourish here. There is also a wonderful rapeseed oil for sale in the farm shop.

Beer

Three friends in Piteå wanted to change beer culture in town. So they started a micro brewery and just to make things clear they named it ‘This is how’. From the start, it was obvious what it was all about: ‘This is how to just pick one PILS’ and ‘This is how to get it foggin’ right’. But when they made the beer for the Nobel Prize banquet after party, the name was obvious: ‘This is how to not spill it’.

30 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Gin

When Café magazine asked their expert Emil Åreng – Sweden’s best bartender and author of the world’s best cocktail book: ‘Salongs i Norrland’ – to name Sweden’s top ten gins, three of them were from the destination Swedish Lapland. Gin Gin from

Piteå came in at place nine as a “work horse” for your dry martini or GT. Ógin by Jón Óskar Arnarson in Skellefteå was placed number six. Jon Oskar is rightly called a genius, for his amazing take on gin and because there is, according to Åreng “frightfully honest

Jokkmokkskorv

stuff” in the bottles. Highest on the list we find Norrbottens Destilleri from Töre, where former poker pro Dennis Bejedal makes ND Forest Dry Gin. According to writer Åreng: “one of my three absolute favourites in Swedish gin history”.

Chocolate

Why not treat yourself to some Arctic Treats. Chocolate pralines made in Kalix with flavours from all over Swedish Lapland. No wonder it tastes like true chocolate and pure joy, or as it says on the box: “heartfelt tasty handmade pralines, just for you”.

The story about the Swedish sausage Falukorv, now with protected designation of origin, is connected to the Falu copper mine, in Dalarna. The mine required large amounts of leather, to make ropes. The by-product, the slaughtered animals, needed to be stored and that led to the sausage. Today, the company Jokkmokkskorv has taken Falukorv to a new level (we recommend the sauna-smoked version). You can also find the Jokkmokkskorv logo on air-dried products such as bresaola, coppa, lomo, pancetta and prosciutto in well-assorted food stores up north.

31 TASTE

Emil Åreng

Photo: Jokkmokkskorv

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

magical light of the midnight

32 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE ROAD TRIP

Photo: Per Lundström

The

sun on the bridge connecting the mainland with Seskarö, in the archipelago of Bothnian Bay.

IN SAUNA VERITAS

IN THE SAUNA, BE ONLY TRUTH SPOKEN

Tornedalen, the borderland between Sweden and Finland, is in many ways unique. The Torne River has never really been a border. Instead, it has tied the two countries together; never dividing, only uniting, to the benefit of sweethearts, smugglers, spies and sauna-bathing travellers. This summer take a road-trip through the promised land of the sauna.

if you believe in the motto of Svenska Bastuakademien, The Swedish Sauna Academy, only truth prevails in the sauna. Then perhaps you have asked yourself this question: Can one find oneself in the sauna?

Let’s say that the whole trip starts on the bridge between Seskarö and the mainland. There’s a fabulous sunset and, since there is no traffic in the middle of the night, you allow yourself to pause and enjoy. In some way, it feels as if the bridge is elsewhere, not in Sweden. Your colleague says, “it’s almost as if this bridge was in Norway.” And someone else even likened Seskarö to a Swedish Key West – which may be a bit of an exaggeration. Meanwhile, you sit still in the car,

marvelling at the light of the midnight sky. This is one of the summer’s many enchanting white nights and, even though it may feel as if you are somewhere else, in Norway or Florida, here is where you want to be. Perfectly still in the summer night.

Haparanda and the neighbouring Finnish border town of Tornio named themselves Eurocity. Here, the river is no border, but the tie that binds. You’ll see, hear and experience this all along your journey westward from the islands of the Bay of Bothnia to the mountain landscape surrounding Riksgränsen. Today you’ve been out to the National Park of Haparanda Archipelago, revitalized in a spa at Sweden’s easternmost mainland point, dined and slept at Stadshotellet, which dates from 1900, and taken a car ride out to Seskarö under the surreal light of the northern summer.

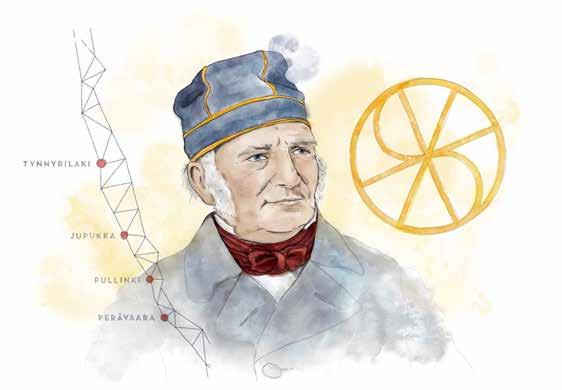

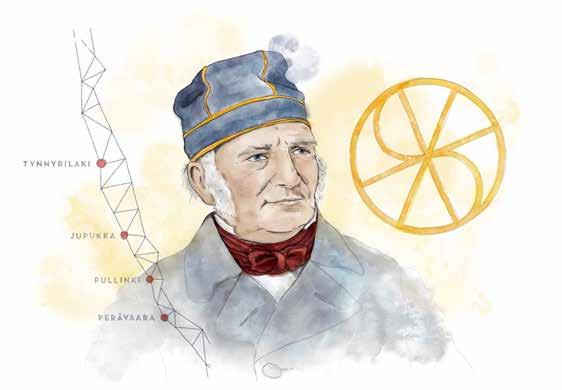

the following morning, you will saunter over the bridge to Tornio. Near the church is a monument commemorating Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve’s expedition to chart the Geodetic Arc. This World Heritage site, the path of Struve’s survey expedition, with triangulations stretching from Odessa on the Black Sea to Fuglenes on Norway’s North Atlantic coast, tells a fabulous story that you will follow for virtually all of your trip.

33 ROAD TRIP

Here, by the church, King Karl XI might also have seen the midnight sun in 1694. But at the stroke of midnight, clouds rolled in and blocked the sun, so the king missed the show. However, he decided to try his luck the following year and in preparation for his return, the round so-called ‘King’s Window’ was installed on the church tower. Unfortunately, the king died before he was able to return and missed out on both the midnight sun and the window.

After a morning stroll – nowhere on the scale of Struve’s expedition – breakfast and careful consideration of whether a new item from IKEA’s northernmost outlet might be needed, your travels continue. Not much distance will be covered today. First, in

that afternoon, after a sauna and a dip in the river, you continue upstream to Risudden/Vitsaniemi. Here, entrepreneur Gunhild Stensmyr, inspired by the Italian Albergho Diffuso concept, has built one the destination’s most interesting hotels; Arthotel Tornedalen. With a flair for exciting design she purchased and renovated a few of the old homesteads, bringing new life to the village. Upon reaching Arthotel, you’re in no hurry and decide to linger a while. Your next destination is Luppioberget and the recently built Lapland View Lodge. You’ll stop over, here on the mountain, admiring yet another captivating view from the comfort of yet another sauna. However, before checking in you decide to take in a few more sights.

Kukkola, some mustard is procured from Pesula, the world’s northernmost mustard grower, after which you take a jaunt to Struve’s Geodetic Arc before pausing for lunch: fresh-smoked whitefish at Kukkolaforsen. Bag-netting for whitefish in the rapids of Kukkola is a cultural heritage, and a more locally sourced lunch can seldom be found. Fresh fish, caught in the river, some metres away, prepared in the adjacent smokehouse and served with fresh potatoes. In addition to rapids and fishing, Kukkola has everything you desire if you’re a sauna aficionado. This is the home of Sweden’s sauna academy, and holds at least thirteen different saunas, among them, two smoke saunas. In times past, the smoke sauna, antibacterial and cleansing, was the undisputed answer to all ills. Children were born in the sauna and the departed rested here, awaiting burial. In mid life, evenings were spent here.

Lake Armasjärvi is interesting from a military history point of view as the site of a major disaster in peacetime. In October 1940, 46 people (44 recruits and two civilians) perished here. They drowned in the frigid water when an overloaded ferry capsized. Historically, Tornedalen has not been far from the scene of conflict. And, although Sweden has not been at war for more than 200 years, our neighbouring countries have not been unscathed. After Armasjärvi you venture into Finland, crossing the bridge at Övertorneå to Yle-Tornio on the Finnish side, and then up the rugged Aavasaksa Hill. Here, you meet Struve once again, and you can also see Tsar Alexander II’s imperial hunting lodge, which was drawn by architect Hugo Saurén. The retreat was built for the Russian tsar, who wished to get away and enjoy the pleasures of hunting in his northern domain. But the Emperor of Russia,

34 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE ROAD TRIP

Haparanda Stadshotell

Kukkola rapids

Photo: Per Lundström

King of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland never got a chance to see his newly built timber lodge. At home, it was a time of turmoil, with the Crimean War raging and other problems brewing. Finally, Tsar Alexander was unlucky to die after the fourth assassination attempt succeeded.

the next day also starts off at a relaxed tempo. Dinner and a sauna take their toll. And the view from the room on Luppioberget makes your bed an even nicer place to be. A fascinating view. You eat breakfast and pack your stuff. The journey proceeds upstream along the river. At Särkilax a chapel has been built anew after the original was washed away in the spring flood.

Here, you might even climb a bird watching tower to do some birding. You drive past Svanstein, where Struve continued recording his measurements of the curvature of planet Earth up on Pullinki. But, since you’re planning to see a few more sights, the hike up Pullinki will have to wait. Just before reaching Pajala, you make a brief stop at Kengisforsen. Kengis bruk, the site of an old ironworks, offers world-class salmon fishing, but is also part of the local industrial heritage and history, together with places such as Svanstein, Masungsbyn and Melderstein. It is a history that is filled with visions, as well as tribulations. After visiting Kengis, you pause for lunch at Bykrogen in Pajala, beside the world’s biggest sundial. That afternoon takes you out to the wetland meadows of Vassikavuoma, and on a short amble up the green hill of Jupukka, the fifth point of measurement on Struve’s expedition along

the river valley. After a visit up on Jupukka, you drive to Arctic River Hotel in Tärendö. And, yes, there is a sauna, a tub and a whole river to bathe in.

the tärendö river is an attraction in itself – the world’s second-largest bifurcation, after Casiquiare in the Amazona. And what, you may ask, is a bifurcation? This means that the Tärendö receives its water, its origin, from the national Torne River, and then discharges it into another national river, the Kalix River. Beyond Pajala, there are actually two alternative routes for your onward journey through Tornedalen. But at Junosuando you take a right and drive northward, crossing the Torne River and proceeding towards Kangosfors, reaching Rd. 99 south of Muodoslompolo. This takes you past the exit to Tynnyrylaki, the northernmost Swedish point of measurement on Struve’s expedition,

35 ROAD TRIP

Arthotel Tornedalen

Lapland View Lodge

36 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE ROAD TRIP

“It’s hard to take in the magnitude of the entire urban relocation; to comprehend how a whole town can pack up and move to a new site. But that’s exactly what is happening.”

Arctic River Lodge Lapland View Lodge

Camp Ripan

Scandic Kiruna

Kristallen

Photo: Scandic

which then continued into Finland, and then to Fuglenes, in the Norwegian municipality of Hammerfest.

In Sweden’s northernmost church village, Karesuando, you visit both the church and a building referred to as Laestadius’s pörte. In the church, you see Bror Hjorth’s classic altarpiece. Priest Lars Levi Laestadius from Jäckvik, in Arjeplog, grew up in a dysfunctional home. After he was ordained he eventually ended up in Karesuando, where he would fight a battle against the alcohol abuse and miserable conditions which plagued many Sámi and settler families. Often, this was a result of their having been tricked into disadvantageous agreements by public officials, the clergy and unscrupulous merchants, who sweetened many a dubious deal with liquor. The revival movement, started by Laestadius, would have a deep and lasting social impact on the entire community. In Laestadius’s pörte (a kind of utility building which doubles as a smokehouse), not far from the beautiful church with Bror Hjort’s famous sculpture, you feel a sense of the simplicity of life as it once was lived here. Then, heading due south, you pass several old, and well-preserved stone bridges beside the E45 on the way to Kiruna.

it is difficult to understand ‘the new Kiruna’. It’s hard to take in the magnitude of the entire urban relocation; to comprehend how a whole town can pack up and move to a new site. But that’s exactly what is happening. Summer 2022 saw the relocation of Kiruna’s old town centre. You meet a fascinating new urban setting as you approach along the E10. You check in at Scandic Hotel, which was designed by architects SandellSandberg. On one side it’s a bit edgy and angular; on the other, more rounded. Somewhat reminiscent of the north and south sides of Giebmegáisi/ Kebnekaise. Or, perhaps, one side of the building can be likened to Giebmegáisi in profile, and the other side is much like the iconic Lapponian Gate, Čuonjávággi. The top-floor bar commands a magnificent view of both the city centre and the surrounding landscape. This is such a very distinctive part of Sweden that it is in some way a provocation to lump it together with the much-clichéd term ‘Norrland’. As a place, the Arctic mining town of Kiruna really is incomparable to anything else in Sweden.

you stay a couple of nights in the newly reawakened town. You’ll visit Nikkaluokta, and then swing by Icehotel later in the day. Eat dinner at Mommas, have a coffee at Spis and walk through the new town which, in a way, is still a construction site and a fresh urban centre. It’s a completely different world. In the new city hall, Kristallen, drawn by architect Henning Larsen, you take the opportunity to visit Länskonstmuseet. The whole building is a great expression of architecture and culture. At Camp Ripan you experience the pleasures of an award-winning spa and enjoy a meal prepared in one of Europe’s most sustainable kitchens. Over dinner, you ponder this sauna sojourn.

From Cape East on the coast via Kukkola, Arthotel Tornedalen – whose sauna by the way was created by designer Christian Halleröd – to Luppioberget and Tärendö, you have landed in Kiruna, and had a sauna at both Scandic and Camp Ripan. Tomorrow you’ll continue westward to Niehku Mountain Villa, where, of course, yet another sauna with a view awaits you.

Here, in the sauna, you realize that the end of your journey is approaching. From the coast to the high country, from sandy beaches to mountaintops, your roadtrip has been magical. 800 kilometres later,

37

ROAD TRIP

Lapland View Lodge

Abisko Canyon

having enjoyed fabulous hospitality, sightseeing and a northern culture. You’re feeling the physical effects of the day’s hike up to Rissajaure (known locally as Trollsjön – Troll Lake), through the amazing Geargevággi, or Kärkevagge. But, aided by the sauna, your aching muscles start to loosen up. Making no haste, you speculate on the next day’s possibilities. You’re considering a day trip up to the mountain Njullá, with Sweden’s most iconic view of Čuonjávággi and a walk down the mountain via the canyon, in Abisko National

Park. Perhaps, then and there, you’re inspired to stay just one more night. You might check in at Abisko Mountain Lodge and sit down to dinner at Fjällköket. Who knows?

The choice is yours; it’s your vacation and this journey is slow travel at its best; an opportunity to take the day just as it comes. You toss a scoopful of water on the hot stones and let the heat pinch your cheeks. Only truth prevails in the sauna and, truth be told, life is really very good right now.

38 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE ROAD TRIP

On the road to Abisko from Riksgränsen, you will get the chance to see uonjávággi, the Lapponian Gate, one of Sweden’s most iconic panoramas.

Geargevággi

Niehku Mountain Villa

Photo: Per Lundström

Keep the fire burning

the swedish sauna academy was founded in Jukkasjärvi in 1988, but now has its home in Kukkolaforsen. In no way does it come as a surprise that the base for the Swedish sauna culture is found in Tornedalen. On the other side of the Torne River, in Finland, sauna culture now counts as a Cultural World Heritage. That really ought to be the case on the Swedish side of the river, too.

Here in the Tornedalen a sauna is an essential part of live. Earlier on, the smoke sauna (because it was

germ-free) was where the people of the Tornedalen gave birth as well as stored their dead until the burial could take place.

There are sauna cultures in other parts of the world: Turkish hamams and Russian banyas, and perhaps you could add places with hot springs too. Rituals and cleanliness are important. So is ‘löyly’, a Finnish word to describe the feeling, or that special heat, that you get from the steam as you throw water on the sauna stove. The effect should be slow, like being enveloped

in an embrace. The steam bouncing off you like a ricochet is bad löyly. Also, a well-designed sauna consists of many parts. The choice of wood for its different components is one of them. Spruce and pine have been used for the walls but is rarely a good idea. There will be resin, and pine tends to warp. Aspen and alder are traditional choices for the benches because they do not secrete resin; alder in particular is at the heart of the sauna culture that has become a World Heritage.

39

Photo: Ted Logart

The sauna at Båtsuoj near Slagnäs, Arjeplog, is one of many great sauna experiences around Swedish Lapland.

Sápmi tales

The story of Sápmi is a colourful one, and an Arctic lifestyle without Sámi knowledge is inconceivable. Manifestly, as bearers of the cultural heritage, Sámi artists of today have a firm footing in the protection of the indigenous people’s land. But from a world in which even subtle details as bootlaces carry a history, we have a great deal to learn.

on display at the 59th La Biennale di Venezia, as part of the exhibition “Il Latte dei Sogni – Milk of dreams”, are works by Britta Marakatt-Labba. The classical sculpture Brickhouse, by Simone Leigh, greets you as you enter the exhibition venue. But barely metres behind Brickhouse, hang Britta’s works. It feels like pausing fo a breath of fresh air. It is austere, unpretentious and strongly symbolic. Britta’s stylistic resistance art, embroidered one careful stitch at a time, is like slow-motion graffiti. People stop in their tracks. They absorb and are absorbed. Approaching the art, they examine the style of the work at close range. Moving a few steps back, they take it all in. In Badje Sohppar, in the Municipal-

ity of Kiruna, Britta has been creating resistance art for more than 40 years. Only in recent years has she gained wider recognition in the art world. Her work Historjá, in the collection of the Arctic University of Norway, in Tromsø, is a 24-metre-long embroidered epic of Sámi history and beliefs. The artwork caused a sensation at the Documenta 14 exhibition, in Kassel, in 2017 and has been compared to the Bayeux Tapestry, another embroidered encyclopaedia. Historjá is also the title of an awardwinning documentary about Britta, by Thomas Jackson. All of a sudden, it is apparent why the world’s most significant art show, has allowed her work to become part of the greater story.

40 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE CULTURE

41 CULTURE

Photo: Carl-Johan Utsi

britta marakatt-labba was not the only artist from Sápmi at the Biennale. The Nordic pavilion, which traditionally shows the works of artists from Finland, Norway and Sweden, is devoted this time entirely to Sápmi. Pauliina Feodoroff, Skolt Sámi from Ivalo, gave a performance called Matriarchy at the Biennale. It had to do with healing, both in relation to nature, and in the relation between Sámi and non-Sámi. Máret Ánne Sara’s art takes its point of departure in her personal experience of how the Norwegian state forced her family to slaughter their reindeer herd. Máret Ánne asks the question: what happens when the laws of another culture are forced upon you and you must break the moral and ethical rules you live by and hold to be true? For a Sámi, the forced slaughter of reindeer goes against all logic. Reindeer are the very foundation of Sámi life. But if this is questioned, what is left? The third artist in the Sámi

Pavilion was Anders Sunna from Kieksiäsvaara who now lives in Jåhkåmåhkke (or Jokkmokk, if you will). Just as it is for Máret Ánne, his art is based on personal experience. It may not seem quite right to call Sunna a street artist, but there is something graffiti-like in his style.

Outside of Krog Lokal in Jåhkåmåhkke, where we eat lunch one day, stands one of Sunna’s works. It is a reminder that the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No.169 was never ratified by the Swedish state. The symbolic value is always recurrent in the Sámi context. It is still a place where the struggle between origins and colonial power persists. Quite simply, the conflict of land-use issues, reindeer grazing lands versus raw materials, becomes increasingly clearer in the everyday lives of the Sámi people.

“Of course, the Biennale was important for me. But I believe it was equally important for the Nordic pavillion.”

42 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

CULTURE

Britta Marakatt-Labba in her studio in Badje Sohppar.

Felled by Britta Marakatt-Labba.

The work Illegal Spirits of Sápmi, which Anders created in Venice in 2023, has been purchased by Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Since before the museum carries other work of Anders. I ask him if he is always so ‘angry’. He laughs and says:

“I am seldom angry. On the contrary, actually. Imagine being able to speak all the world’s languages without saying a sound. To reach people’s hearts first and then their consciousness. The anger you are carrying suddenly finds a way to emerge, but in a more creative form, stronger than iron. Art is that.”

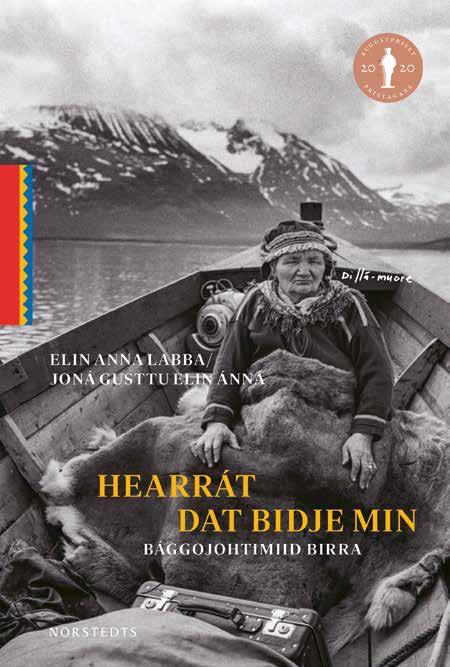

the sámi tradition is largely one of oral history. Sámi, as a written language, did not emerge until the 1950s. Early on, there was nothing written to fall back on; written historical accounts were nothing but interpretations about the Sámi but they were not by the Sámi. There have been exceptions, though almost always at the discretion of church or state. Naturally, this has impacted everyone’s chances for learning and understanding.

Even if you live here, in the middle of Sápmi, it’s quite possible that you know the names of more indigenous peoples of North America than you know the

names of samebyar (reindeer husbandry associations) in your own region. In school you may never have been taught about forced relocation or assimilation, even if you are well aware that some of your classmates’ forbears had to go through all of that. And to complicate things even more, that there is a common Sámi story is never straightforward; instead, there is one story for every individual who tells it. This is complex, in every way that life is complex. Britta Marakatt-Labba says:

“It’s double, in some way. In Kiruna, when I went to the nomad school, I was just a ‘Lappdjävel’. Something undesirable. In Gothenburg, when I studied art and design at Konstindustriskolan, I was ‘the Sámi’. My origin was exotic and exciting.”

and, for outsiders, it is sometimes difficult not to focus our attention on the exotic and exciting. In the colourful stories, the colours and designs of garments reveal a person’s origins. It is a place where simple artefacts, utility items such as knives, become incomparable works of art. How fascinating it is when everyday, practical items such as bootlaces are also part of a story. The obviously colourful and the pride and beauty implicit in the Sámi story often take second place

43

Photo: Hans-Olof Utsi

CULTURE

behind stories of struggle and resistance in today’s media stream. And it is also often difficult for an outsider to comprehend the struggle and anguish that are never very far away in the day-to-day life. Naturally, you have no special emotional attachment to the steak you pick up at your grocery store. But if you have marked the ear of a reindeer calf, and then followed the animal across the grazing lands for the rest of its life, things are different.

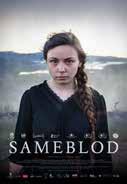

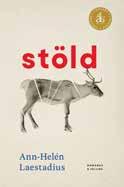

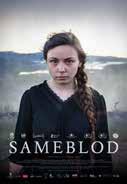

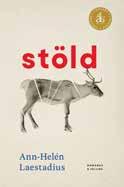

To that, add the historical Christianisation and Swedification of a people whose identity was thought to be of little value. Then, add the outcomes of modern forestry practice, hydroelectric power development, urban development and climate change, and you will begin to understand the sense of vulnerability that these works of art embody, whether they be artefacts, songs or writings. The nationally and internationally award-winning film Sameblod, by Amanda Kernell, exposes this era of racial biology and cultural assault. We have all been young and occasionally lost, and young people have always wondered what they will be when they grow up. But in Kernell’s film this longing also becomes a longing to obliterate one’s identity, and a disdain for one’s origins and history.

44 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

CULTURE

Photo: Andy Anderson

“Imagine being able to speak all the world’s languages without saying a sound. To reach people’s hearts first and then their consciousness.

The anger you are carrying suddenly finds a way to emerge but in a more creative form, stronger than iron. Art is that.”

anders sunna

Anders Sunna

in the early 1900s a newly awakened Sámi identity began to emerge in the public sphere. As an example, the Sámi National Day is held on February 6th to commemorate the first Sámi political congress, which took place in Trondheim in Norway, in 1917.

Of course, the Sámi story is also its vocal music tradition – jojk. During the 1960s, when interest in their own culture blossomed, Nils-Aslak Valkeapää revived the jojk and brought it to the modern society. His first record, Joikuja, was released in 1968. The multifaceted artist Valkeapää, or Áillohas, as he is known, created music for the film Vägvisaren in 1987, performed at the 1994 Winter Olympics, in Lillehammer, and was awarded both the Nordic Council Literature Prize and the Prix Italia.

Among Sámi, Valkeapää’s Sámi eatnan duoddariid is considered a national jojk and has in some way become Sápmi’s unofficial national anthem. That the jojk now features on the modern Nordic music scene, and that Sámi rappers and other artists have introduced the jojk into popular culture is self-evident and appreciated. When artist Sofia Jannok, from Seidegavas, in the Luokta-Mavas sameby, was awarded an honorary doctorate from Luleå University of Technology, in 2021, she said in an interview with Swedish Radio that she wished her grandparents were still alive.

“I would have liked it if they had known that we could receive honorary doctorates. It would probably have been inconceivable for them.” But someone always has to be the first to break a trail.

britta marakatt-labba began her career as an artist during the Alta uprising in Norway. It took many years to resolve the conflict; just as her embroideries take many years to create. In 1981,