Prepare to be revolted as you see, smell, and taste some of the world’s most disgusting foods. Trip Advisor lists Malmö’s Disgusting Food Museum as the number one thing to do in the city, but it is not for the weak of stomach.

By Kajsa Norman

The Disgusting Food Museum invites visitors to reflect on the nature of disgust and reminds us that what disgusts us can change with time. Two hundred years ago, lobster was considered so disgusting it was only fed to prisoners and slaves. Today, most regard it as a luxurious treat. The museum cautions that we may need to continue to adjust our palates in the future in order to embrace more environmentally sustainable foods and alternative protein sources such as insects and lab-grown meat.

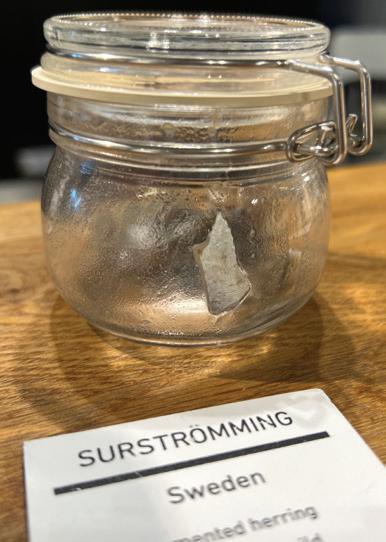

For those eager to challenge themselves, there is a tasting bar where one can sample crickets, ants, different types of worms and maggots, stinky cheeses, surströmming (fermented herring) and Hàkarl (fermented shark).

If you can’t bring yourself to taste them, there is always the opportunity to simply smell several of the pungent dishes. However, just seeing them is often stomach-turning enough and all visitors receive a vomit bag upon entry.

The Museum of Disgusting Food reminds us that disgust is cultural. We’re biased in favor of the foods we have grown up with, but what we consider delicious someone from another culture may find disgusting.

Here are some examples.

While there are many examples of disgusting cheeses on display, these two Italian specialities from the island of Sardinia are amongst the most repugnant. Su Callu is made through slaughtering a baby goat immediately after it drinks milk. The kid’s stomach, which contains undigested milk, is rubbed with salt and hung to dry for months to produce the cheese. Casu Marzu is produced through cutting open a whole pecorino cheese and leaving it outside for cheese flies to lay eggs in it. Their larvae then feast on the cheese, breaking down the fats. The larvae excrement turns into a partially digested, semi-liquid, soft cheese. The larvae can leap up to 15 cm when disturbed so consumers of the cheese must protect their eyes

from jumping larvae as they can bore into their new host. Commericial sales of Casu Marzu is now ilegal in Italy and across the EU due to food safety regulations.

The museum features many Chinese culinary delights, such as eggs soaked in the urine of virgin boys, different types of penises, spicy baby rabbit heads, rabbit brain paté, turtle soup, and mouse wine. To make the latter, baby mice are drowned and brewed in rice wine. The mice have to be newly born, as they must be blind and hairless. The brew ferments for up to a year before being consumed. Visitors are also reminded that dogs remain a popular food in several Asian countries, with an estimated 25 million dogs consumed every year.

Top: In China, eating bull penis is considered an aphrodisiac. Below, mouse wine from China.

Also known as a Mongolian Mary, this beverage consists of pickled sheep eyeballs and tomato juice. A popular hangover cure that dates back to the days of Genghis Khan.

In the Peruvian Andes, Guinea pigs, known as cuy, are consumed fried or grilled. There is even an annual festival in the city of Cusco where the rodents are dressed up in fancy clothing for a fashion show before being awarded prizes in categories such as best dressed and tastiest. Another Peruvian delicacy is Jugo de Rana, or frog juice, which is made through skinning a frog and then putting it in the blender with water, quail eggs, honey, and spice. The frothy goo is strained to remove any bone fragments before being served.

Balut is a popular street food in the Philippines. It is a boiled duck egg with a partially developed fetus. First you sip the broth, then you eat the

Top: Guinea pigs, known as cuy, is a Peruvian delicacy. Below: Balut from the Philippines. fetus and yolk straigh from the egg as the beak, feathers and bones are still soft enough to be chewed.

What then are the disgusting dishes on display for North America and Sweden? Well, there are bull testicles, known in the US as Rocky Mountain Oysters and in Canada as Prairie Oysters. But also foods most North Americans might not consider disgusting, for example products infused with chemical additives to create nearinfinite shelf-life, such as Twinkies, Pop-Tarts and SPAM, the canned pork whose name later became synonymous with unwanted emails. Even Jell-O and Root Beer are featured as examples of disgusting foods. “The medicinal sweet and spicy taste is appreciated by Americans but elsewhere described as like drinking toothpaste,” reads the sign under Root Beer.

For Sweden, surströmming (fermented herring) is of course on display, but also salty liquorice (which apparently gets its flavor from ammonium chloride, a chemical also used to clean metals and make industrial fertilizers) and gelatine sweets. The sign informs the visitor that gelatine is made through boiling the waste generated during animal slaughtering and processing – skins, bones and unused body parts. Swedes consume an average of 16 kg gelatine candy per person and year.

The last section of the tasting bar is devoted to extreme spice, featuring chili sauces with names like Hellfire Doomed, Grim Reaper, and Toxic Waste. For the last and final chili, visitors who wish to sample must sign a waiver that reads:

“The chili I’m about to try is 9 million scoville, among the strongest on the planet. I fully understand that tasting said chili will most likely cause severe stomach cramps, pain, suffering, crying, and could cause severe problems. I hereby acknolwedge that the choice to taste a chili extract of 9 million scoville is idiotic, and I’m ready to face the consequences head on.”

I, like many visitors, still can’t resist the challenge. The guy trying it before me vomits into a trash can and the black board which records the number of days since the last vomit is reset to zero. A total of 486 vomits have been logged thus far. I manage to not toss my crickets and worms, even after the burning chili, but I leave the museum teary-eyed and slightly nauseous. It will take some time before I am able to eat again.

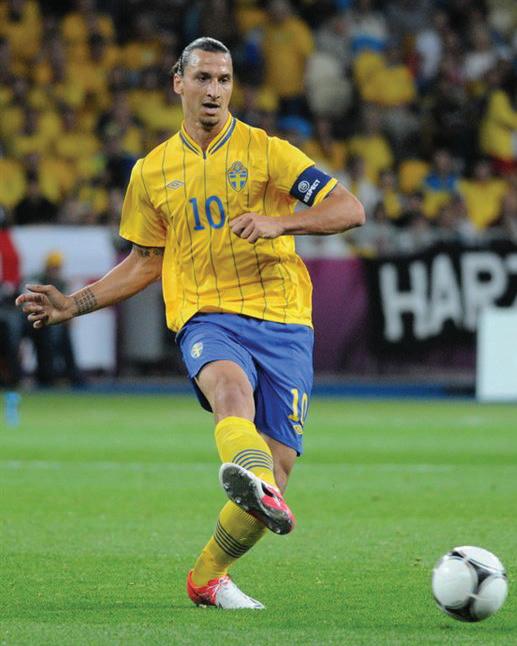

One of the greatest strikers of all time, Zlatan Ibrahimovic is Sweden’s most renowned soccer player with over 570 career goals and 34 trophies. And it all began in Rosengård.

By Noelle Norman

The son of a Croatian mother and Bosnian father, Zlatan grew up in Rosengård, Malmö. His mother worked as a cleaner and his father as a property caretaker. Family life was messy and Zlatan stayed away from home as much as possible, playing soccer and stealing bikes.

“I picked the locks. I got to be an expert at it. Boom, boom – and the bike was mine. I was the bicycle thief,” he writes in his autobiography, I Am Zlatan Ibrahimovic. “People have asked me what I would have done if I hadn’t become a footballer. I have no idea. Maybe I would have become a criminal.”

Instead, Zlatan developed his talent for soccer, playing with other kids in the courtyards between Rosengård’s apartment buildings. He would often sleep with his ball and imagine the tricks he was going to do the next day. “It was like a film that was rolling constantly,” he writes.

His first club was called MBI, Malmö Ball and Sporting Association.

“I was just six years old when I started. We played on a gravel pitch behind some green shacks, and I would ride to training sessions on stolen bikes and probably wasn’t all that well-behaved.”

Zlatan recalls constantly being told to pass the ball – something he would spend the better part of his career avoiding.

“I told them to go to hell and changed clubs many times before I

ended up at the FBK Balkan club. That was something else. At MBI, the Swedish dads would stand around and call out, ‘Come on, lads. Good work!’ At Balkan, it was more like, ‘I’ll do your mum up the arse.’ They were mental Yugoslavs who smoked like chimneys and flung their boots about, and I thought, Great, just like at home. I love it here!”

Zlatan had not yet turned two when his parents got divorced.

“I don’t remember any of it. That’s probably just as well. It wasn’t a good marriage, from what I understand. It was noisy and messy, and they’d got married so Dad could get a residency permit, and I assume that it was natural that all of us ended up with Mum.”

The conflicts at home soon got worse. One of Zlatan’s half-sisters was caught hiding hard drugs in their

apartment, his mother got arrested for receiveing stolen goods, and she would sometimes beat Zlatan and his sister Sanela. Social Services got involved and in March 1991, Zlatan’s father Sefik got custody of him. Life didn’t turn out much better at his dad’s, though, as Sefik was consumed by the war in Yugoslavia and the relatives left behind.

“He would sit on his own and drink. There was no company. Above all, there was nothing in the fridge. I stayed out all the time, playing football and riding round on stolen bikes, and I’d often come home hungry as a wolf. I’d fling open the cupboard doors and think, please, please, let there be something there.”

More often than not, there was just beer. To make a few bucks. Zlatan would collect the cans and take them in to collect the deposit, sometimes even emptying full cans down the drain.

Just like his peers, he was careful never to show himself vulnerable.

“All of us lads played at being cocky. Anything could set us off, and things weren’t easy at home – not by any stretch of the imagination… we didn’t go in for hugs and that sort of thing. Nobody asked, How was your day today, little Zlatan? There was none of that. There was no adult around who helped with your homework or asked you about your problems. You had to deal with things yourself, and there was no whining if someone had been nasty to you.”

Downtown Malmö was not far away, but it was another world. Zlatan was 17 years old the first time he went into the city centre, and says he knew nothing of life there, or of mainstream Swedish culture in general.

“Swedish TV didn’t exist as far as we were concerned. It just didn’t register. I was twenty years old before I saw my first Swedish film, and I didn’t have a clue about any Swedish heroes or sporting figures, like Ingemar Stenmark or anybody.”

Instead, Zlatan’s idol was Muhammad Ali, whom he admired for doing things his own way, no matter what people said. “That’s the way I wanted to be, and I imitated some of his things, like, I am the greatest. You

needed to have a tough attitude in Rosengård, and if you heard anybody talking trash – the worst was to be called a pussy – you couldn’t back down.”

The cockiness Zlatan developed in Rosengård would stick with him throughout his career, earning him both fans and critics. While he became immensely popular in the Malmö area, some Swedes considered him too arrogant and full of himself as he routinely defied the Law of Jante, the list of social rules centered on humility which all Swedes, including athletes, are pressured to abide by.

Don’t think you’re anything special. Don’t think you’re as good as we. Don’t think you’re smarter than we.

Don’t think you’re going to amount to anything.

Well, Zlatan thought, and articulated, all those things.

“My thing was I would both talk and perform... I wanted to be the best while being cocky,” he writes.

During a professional soccer career spanning four decades at clubs such as Juventus, AC Milan, Barcelona, Paris Saint-Germain, Manchester United, and LA Galaxy, Zlatan provided irrefutable proof of his soccer genius. When he retired in 2023, he was Sweden’s all-time leading scorer with 62 goals for the national team, and his 35-yard “bicycle kick” goal for Sweden against England in 2012 is still considered one of the greatest goals of all time.

Can food convey a sense of home? At Malmö restaurant Vollmers, the aim is to immerse visitors in the culinary delights of Skåne, infused with childhood memories transcending time and space.

By Kajsa Norman

In 1920, Ebbe and Bertha Vollmer came from Germany to Malmö. They started a haberdashery – a gentlemen’s clothing store – that soon became the city’s most reputable. But one day everything changed. Ebbe was seriously injured in a train accident and Bertha realized that from now on, it would be up to her to provide for the family. She started what would become a veritable restaurant empire in Skåne.

When Bertha passed away, her three children inherited the restaurants, and for generations to come, the art of preparing, serving and enjoying great food would remain a key part of their identity.

“Every Sunday we had dinner together. If we didn’t sit straight, or if we had our elbows on the table,

grandma came and stabbed us with a fork,” laughs Mats Vollmer. “We still use those same 1948 silver forks from our family’s first roadside inn when we now set the tables of our restaurant.”

With a family history so deeply shaped by food, it was natural for both Mats and his brother Ebbe (junior) to pursue careers in the restaurant industry. They both had a flair for fine dining and worked for the Michelin 3-star Restaurant “Restaurant Gordon Ramsay” in London. Mats then went on to work with some of the best chefs in Scandinavia, while Ebbe headed east to work at elite restaurants in Singapore. When Ebbe returned to Sweden, the two brothers decided the time was ripe to launch something of their own and in 2011, Vollmers was born.

Mats and Ebbe wanted to con-

tinue the legacy of luxury that had been associated with the tailor-made suits their great-grandparents sold at the haberdashery. After all it was the profits from that business which had allowed great-grandmother Bertha to launch her first restaurant. To honor that heritage, they chose the clothes hanger as the symbol of their restaurant.

Vollmers was off to a great start, but after about two years, the novelty had worn off and there were many empty tables. Ebbe decided to branch out and open a new restaurant while Mats dug in and advertised for a Head Sommelier and Maitre D’. In 2013, Karin joined the team. That summer Mats did all the cooking and Karin took care of everything else. Working side by side with a shared vision, the two achieved

excellence and fell in love.

“We scored really well in the White Guide even though we were on our own, competing against restaurants with kitchen teams of 15 people,” Mats recalls.

Mats describes himself as very competitive, so when he learned that the Michelin team would start testing restaurants in Malmö, he immediately aimed for a star.

“Malmö has always been belittled and scorned by the rest of Sweden. This creates a desire to show everybody, to show ’big brother’, that we are just as good, if not better,” he says.

And to do so meant embracing the culinary heritage of their Skåne roots.

“The most important thing in cooking is authenticity and to be grounded in what you do. Our menu reflects our Scanian traditions and memories as much as our imagination and desire to innovate. We create from what grows around us when it is in season. Because that’s when the produce has the most vitality and tastes its very best,” says Mats.

quality.

“I am not from the Michelin world. That was Mats’ domain. I was never very impressed by Michelin establishments. I found people who worked at those types of places to be so pretentious,” she says and adds that she learned to strive for excellence in service while working at Pizza Hut.

At the age of 19, Karin started working seasonal gigs in different parts of the hospitality industry, first in Swedish ski resort Åre, then in Gotland. She worked in arenas, onboard cruise ships, and even in South Africa. At the age of 25, she finally returned home to Malmö where she became a

and pears are turned into juice and purée served at the restaurant. They use the fig leaves from their fig trees for oil, their gooseberries for gooseberry marmalade. They pick spruce tips, sweet cherries, black and red currants and incorporate them all into their culinary creations.

In 2021, they even planted grapevines, and in 2023 they produced their first batch of wine – Vollmerska gården, based on the Solaris grape, a hybrid white wine variety developed in Germany.

“It can be used for sparkling, dry, demi-sweet and sweet wines – the full range,” says Karin, who was named Sommelier of the Year in 2024. “And it goes really well with the flavors of the Scanian cuisine.”

“The young team provide cheerful service at this intimate restaurant on a cobbled street in the Old Town. The surprise menu comes with numerous extra courses, including some inspired by the owners’ childhood memories, and texture and acidity are used to good effect in the creative, sophisticated dishes.”

The Michelin Guide

Sommelier and found employment at Vollmers.

In 2015, Vollmers became one of only three restaurants in Malmö to be awarded a Michelin star. And just two years later, in 2017, they were the only restaurant in Malmö to be awarded two Michelin stars, a level of excellence they’ve maintained ever since,

“Michelin has tested restaurants in Gothenburg, Sweden’s second largest city, since 1989 but nobody there has ever been awarded two stars so for a place in Malmö to achieve this after just two years of testing is huge,” says Mats.

For Karin it was less about the stars and more about the recognition of

“I was intrigued by Mats’ dedication to creating one of Sweden’s very best restaurants,” she says. “But the whole Michelin business was less important to me.”

That is, until she realized what the award meant in practice.

“Within two hours of being awarded our second star, we had 22,000 people visiting our website at once. It crashed as people were trying to make bookings,” she laughs.

Never again would they have to worry about investing in marketing. Suddenly, Mats and Karin could afford to hire staff and have some time for themselves. They bought a dog, and a farm, and now they cultivate much of the produce they need. Their apples

The first harvest yielded 92 bottles of wine.

“But we hope to produce 300 bottles a year within a year or two,” says Mats.

The Vollmers seem to never run out of dreams and challenges. In 2024, Karin gave birth to a beautiful baby boy, but becoming parents is not likely to slow them down. Always looking for ways to improve, they have their hearts set on earning a third star, the highest Michelin rating possible and one only given to restaurants with “exceptional cuisine that is worth a special journey”.

What will it take to get there?

“We must consistently be that little bit better. It’s in the details. It’s hard to explain,” says Mats. “It’s not that much more, yet it’s infinitely more.”

Photos from left: Karin and Mats with their son and dogs. Wine from Vollmerska gården served with homemade gooseberry marmalade and an assortment of mild cheese. Mats at the vineyard. Dishes at Vollmers are created from what grows locally and is in season.

Hope you enjoyed this sample of Swedish Press.

To read more, please click the link https://swedishpress.com/ subscription to subscribe.