HE RITAG E

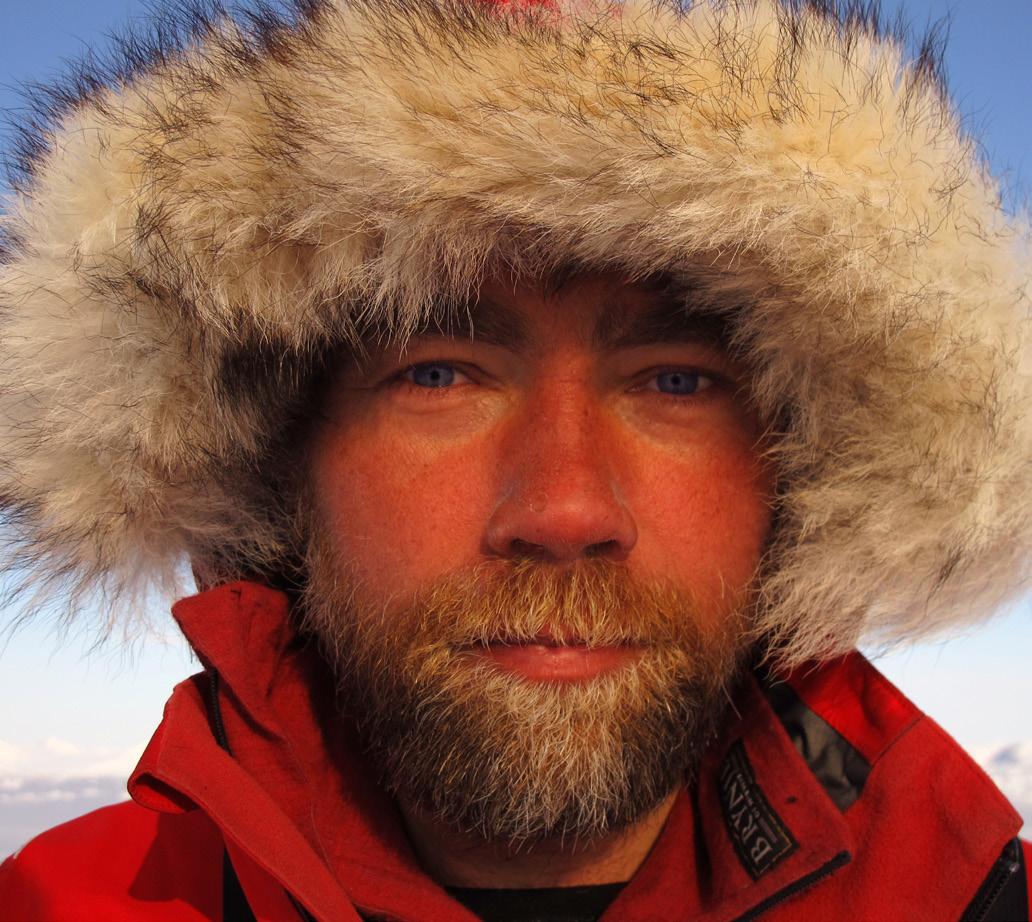

A Move to America in 1868 Early Swedish emigration was also fueled by religious controversy. Many, including the Hill family, were influenced by the revivalist movements that swept through Sweden in the mid-1800s. The Lutheran State Church tolerated no dissention and discriminated all non-members, whereas the United States was seen as the beacon of religious freedom.

{

}

Samuel’s Diary Part 5

Diary Kept on the Journey to America in 1868 by Samuel Magnus Hill Introduction and translation by Lars Nordström [Monday May] 11th We landed at night, and when we woke up we saw Hull, one of England’s large cities, and my eye was captivated by a great many contrivances and machines. The ship was towed to the dock, where the freight was unloaded, and at 12:30 we were allowed to disembark. We had to walk far to an emigrant lodging house, and I remember how tired I was because I had to carry August on my back. My mother and father carried our luggage. Mother also carried my sister Augusta. We were given different rooms in the lodging house and seated around a long, narrow table, and food was brought out and we could eat as much as we wanted. But quite a few had had their appetites ruined at sea. There was a big difference compared to our accommodations in Gothenburg. Here we had sufficient space both at the dining tables and in our sleeping quarters. We had good beds and small, neat rooms to stay in. For breakfast and supper we were served coffee and sandwiches, and for dinner soup and meat, or sausage and bread. The only drawback was that the bread was salty, so it did not taste as good as it looked. The climate change was great too, and that was somewhat dispiriting. It was so warm in England that we had to open the windows. We were so happy that we could rest and remained still that day. [Tuesday May] 12th All the emigrants were allowed to walk to a park located five kilometers from our lodgings. It was rather far, but it was worth it. We got to see a number of beautiful things which we otherwise would not have seen. But our old neighbors, the trees, did not appear to do well in this climate. The aspen stood there red and bald, [as did] a coniferous bush with dry and red [needles]. A couple of birches grew there and they were green and leafy. Bushes of pine grew here and there and their needles were 6 or 7 inches long. The juniper had thick and soft needles, the rowan was in bloom, the horse chestnut, the whitebeam, the cherry and the boxwood thrived, and leafy vines clung several feet high on the brick walls. The grass was forked 1 and had thick roots, but the ground was cracked open from drought, so that it needed to be continually softened by rain, because this was a clay soil and hard as brick to walk on. We saw cattle and cows, but no oxen. [We also saw] sheep, as big as one-year-old calves, with warm and thick fleeces. There were both small and large horses, [some] so small that I had never seen such small ones; they were like billy-goats and they pulled large carriages. The larger horses one can imagine like elephants, the cartwheels were 6 feet high and everything else in proportion. They were draft horses.

It is unclear what this dialect word means, but the root meaning of the word is “broken” or “split,” neither of which really seem to fit.

1

[ ]

July/August 2013 16