93 minute read

A VOICE FOR THE SPORT

FEATURES

014 WOMEN’S NCAAs: A NEW NO. 1

Advertisement

For the first time in the history of the NCAA Division I Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships—since 1982—the University of Virginia finished first. It was also the first time it cracked the top 5 with its previous highest finish sixth in 2019. •VIRGINIA’S ROAD TO HISTORY by Dan D’Addona •NC STATE ADDS TO ACC DOMINANCE by Dan D’Addona •THE TALK OF THE MEET: MAGGIE MacNEIL by John Lohn

018 MEN’S NCAAs: THE PERFECT RETIREMENT GIFT

Days before their coach, Eddie Reese, officially announced his retirement from coaching after 43 years, the Texas men’s team won their 15th men’s NCAA national team championship. •THIS ONE’S FOR EDDIE! by Andy Ross •SCINTILLATING PERFORMANCES: SHAINE CASAS & RYAN HOFFER by John Lohn •PATIENCE REWARDED: MAX McHUGH & NICK ALBIERO by Andy Ross

022 NCAA D-II CHAMPS: SOME THINGS NEVER SEEM TO CHANGE

by Andy Ross A year into the pandemic that has completely changed our world, Queens University of Charlotte brought about some stability to the 2021 NCAA Division II Swimming and Diving Championships by sweeping their sixth straight women’s and men’s team titles.

023 NO LIMITS!

by David Rieder Claire Curzan has been swimming fast since she was a young age grouper and has continued to do so in high school. Last March, she came within 13-hundredths of the American record in the short course 100 fly, and in April, she found herself within 22-hundredths of the long course U.S. best. She’s versatile, she’s coachable, she has international experience, and she’s moved from a fringe Olympic contender to an Olympic favorite. Curzan is only 16, and her promising future couldn’t be brighter.

026 TAKEOFF TO TOKYO: WHEN IRISH EYES WEREN’T SMILING

by John Lohn Ireland’ s Michelle Smith—a four-time Olympic medalist in 1996 who received a four-year ban from the sport in 1998 for tampering with a doping sample—has been defined as being a poster girl for cheating, and by her willingness to cut corners and take advantage of performance-enhancing drug use to make the leap from an athlete of very-good skill to one of elite status.

029 50 SWIMMERS, 6 MEDALS

by Dan D’Addona The Tokyo Olympics will mark the fourth occasion that open water swimming will be contested on the Olympic level, and even a 10-kilometer marathon race can bring exciting moments and dramatic finishes.

030 JOSH MATHENY: RISING STAR

by Matthew De George From a middle-schooler newly committed to swimming full-time in 2016, the future looks encouraging for 18-year-old Josh Matheny, who approaches the U.S. Olympic Trials for Tokyo in June as a dark horse to make the team in men’s breaststroke.

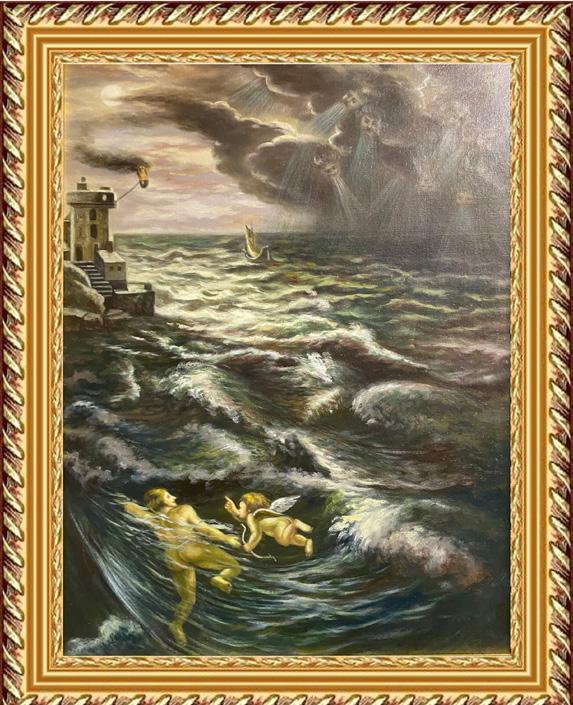

032 ISHOF: THE ART OF SWIMMING

by Bruce Wigo This is the story of Hero and Leander, Lord Byron and the birth of open water swimming.

035 NUTRITION: HYDRATION— BEYOND THIRST!

by Dawn Weatherwax Hydration truly has a daily importance for all kinds of swimmers from age groupers to Olympians to Masters swimmers, but it tends to get more notoriety when the weather gets warmer.

COACHING

012 THE POWER OF POSITIVE COACHING

by Michael J. Stott Relationships built upon honesty, trust and communication go a long way toward cementing a bond between coach and athlete. Coupling that with knowledge of the individual first and athlete second produces a positive working relationship that can last for a lifetime.

16

ON THE COVER Many consider Eddie Reese to be the greatest coach of all time. Two days after the conclusion of the 2021 NCAA Division I Men’s Swimming and Diving Championships in March, Reese announced his retirement, closing the door on one of the most successful coaching careers for anyone in the sport of swimming and the entire landscape of college sports. Reese’s 15 national titles are the most for any coach in NCAA Division I men’s swimming—four more than Ohio State’s Mike Peppe, who won 11 titles from 1943-62...and three more than Michigan’s 12 titles under four different coaches between 1937 and 2013. (See feature, pages 16-19.) [ PHOTO COURTESY ISHOF ARCHIVE]

038 SWIMMING TECHNIQUE CONCEPTS: MAXIMIZING SWIMMING VELOCITY (Part 1)—STROKE RATE vs. STROKE LENGTH

by Rod Havriluk Swimming velocity is the criterion measure for swimming performance and is the product of stroke length and stroke rate. This article explains how stroke length and stroke rate vary and how stroke time provides insight into maximizing swimming velocity.

042 Q&A WITH COACH STEVE HAUFLER

by Michael J. Stott

044 HOW THEY TRAIN CHARLOTTE SHAMIA

by Michael J. Stott

TRAINING

037 DRYSIDE TRAINING: THE IM DRYLAND CIRCUIT

by J.R. Rosania

JUNIOR SWIMMER

047 UP & COMERS: TEAGAN O’DELL

by Shoshanna Rutemiller

COLUMNS

008 A VOICE FOR THE SPORT

011 DID YOU KNOW: ABOUT THE MOREHOUSE TIGER SHARKS?

046 THE OFFICIAL WORD

048 GUTTERTALK

049 PARTING SHOT

THANK YOU, EDDIE!

BY JOHN LOHN

Endings are inevitable. They are part of life, and as much as we may want to rev up the time machine and buy a few more minutes before the farewell becomes official, that is not the way it works. Acceptance is, simply, mandatory.

Over the past few years, we knew the end of the Eddie Reese era at the University of Texas was approaching. With each passing season, the same question arose: How long will he coach? It’s not that Eddie wasn’t producing. Quite the contrary. Heck, the man has guided the Longhorns to team titles at five of the past six NCAA Championships, including the crown this past campaign.

But when a man creeps into his upper 70s and has given all of himself to the sport for more than a half-century, including the past 43 years at Texas, the time and place comes to say: “That’s a wrap.” That day arrived for Reese during his team’s latest championship reign, and he made it official just two days after the Longhorns lifted their 15th NCAA title—all under the guidance of Reese.

“When people get together with the mindset of accomplishing something, even though it is tough during that year in time, it just adds up to something truly amazing,” Reese said. “I want to thank those guys who trusted me, did all the hard workouts and made the sacrifices in and out of the water. It has been an honor for me to be a part of this program.”

It has been an honor to have Eddie Reese influence the sport for the better part of his life.

It is easy to look at Reese’s career from the standpoint of accomplishments. No one has won as many NCAA championships. He has guided three United States Olympic squads and served as an assistant on four others. His athletes have captured more than 100 NCAA titles and 29 Olympic gold medals. He was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 2002.

Yet, his biggest influence is measured outside the pool. He has been called a father figure. A mentor. A motivator. A friend. A jokester. A devoted family man. When those titles are used to describe a man, it is clear his meaning stretches well beyond coach. So, when word of Reese’s decision started to seep through the swimming world, many tears of appreciation were unsurprisingly shed.

“Something really special about Eddie is he doesn’t really view us as athletes or point scorers,” said current Texas star Drew Kibler. “He views us all as human beings and wants what is best for us as human beings, and that is how it has always been. He always cares, even during the hard practices. It makes you see the value in yourself and makes everybody want to be the best. The culture makes you want to work and where you can take these roads. Eddie has a different way of going about these things, and he is just such a phenomenal man.”

Although Reese will be officially retired once the United States Olympic Trials and Olympic Games in Tokyo unfold, he won’t disappear from the pool deck. He will assume the title of coach emeritus and plans to stop by practices and impart the wisdom he has long possessed. But he’ll also have more time to spend with his family, including his wife, Elinor, and enjoy favorite pastimes such as hunting and fishing.

As for the sport? Well, let’s just say that Eddie Reese is not going to be forgotten. His record will stand as a measuring stick for others, the bar raised to a height that will be difficult to reach. Meanwhile, athletes and coaches will share stories and exchange some of the jokes—good and bad—that have been trademarks of Reese for years.

Few individuals in the sports world are known merely by their first name. In our sport, Eddie fits that bill. He is an icon. He is a legend. He personifies greatness—as a man and a coach.

So, we end this column in the simplest of ways: Thank you.

John Lohn

Associate Editor-in-Chief Swimming World Magazine

PUBLISHING, CIRCULATION AND ACCOUNTING

www.SwimmingWorldMagazine.com

Publisher, CEO - Brent T. Rutemiller BrentR@SwimmingWorld.com

Associate Editor-in-Chief - John Lohn Lohn@SwimmingWorld.com

Operations Manager - Laurie Marchwinski LaurieM@ishof.org

Production Editor - Taylor Brien TaylorB@SwimmingWorld.com

Circulation/Membership - Lauren Serowik Lauren@ishof.org

Accounting - Marcia Meiners Marcia@ishof.org

EDITORIAL, PRODUCTION, ADVERTISING, MARKETING AND MERCHANDISING OFFICE

One Hall of Fame Drive, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33316 Toll Free: 800.511.3029 Phone: 954.462.6536 www.SwimmingWorldMagazine.com

EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION

Editorial@SwimmingWorld.com

Senior Editor - Bob Ingram BobI@SwimmingWorld.com

Managing Editor - Dan D’Addona DanD@SwimmingWorld.com

Design Director - Joseph Johnson JoeJ@SwimmingWorld.com

Historian - Bruce Wigo

Staff Writers - Michael J. Stott, David Rieder, Shoshanna Rutemiller, Andy Ross, Michael Randazzo, Taylor Brien

Fitness Trainer - J.R. Rosania

Chief Photographer - Peter H. Bick

SwimmingWorldMagazine.com WebMaster: WebMaster@SwimmingWorld.com

ADVERTISING, MARKETING AND MERCHANDISING

Advertising@SwimmingWorld.com

Marketing Assistant - Meg Keller-Marvin Meg@SwimmingWorld.com

INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENTS

Americas: Matthew De George (USA) Africa: Chaker Belhadj (TUN) Australia: Wayne Goldsmith, Ian Hanson Europe: Norbert Agh (HUN), Liz Byrnes (GBR), Camillo Cametti (ITA), Oene Rusticus (NED), Rokur Jakupsstovu (FAR) Japan: Hideki Mochizuki Middle East: Baruch “Buky” Chass, Ph.D. (ISR) South Africa: Neville Smith (RSA) South America: Jorge Aguado (ARG)

PHOTOGRAPHERS/SWTV

Peter H. Bick, USA Today Sports Images, Reuters, Getty Images

of us need the security of a black environment today.” Dr. Andrew Brown, the first African American to hold a national record and the No. 1-ranked prep school AllAmerican in the 50 yard freestyle in 1970, chose Morehouse for the same reason. “Dr. Haines is a man we can identify with,” said team Captain Mike Wright. “He’s the Big Daddy (6-4, 225 pounds). He’s really too busy to give us the time we need, but then he’ll come down nights and on weekends to open the pool. He does it all—helps us with our problems, gets us out of jail and keeps us at the books.” Today, there’s a perception that with the visible success of swimmers such as Cullen Jones and Simone Manual, African Americans are new to the sport of swimming, but ?ABOUT THE MOREHOUSE TIGER SHARKS? DID YOU KNOW BY BRUCE WIGO there’s actually a very rich history of black swimming during

In the history of collegiate athletics, few teams have dominated their the era of racial segregation—and the Rise and Fall of HBCU leagues like the Morehouse College Tiger Sharks did from 1958 to swimming is a story that needs to be told. Today, Howard is the only 1975. During the 17 years of the program’s existence, the Morehouse HBCU to sponsor a varsity swimming team. swim team from Atlanta, Ga. won 13 Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Conference Championships and boasted a record of 255 wins against Bruce Wigo, historian and consultant at the International Swimming only 25 losses. Hall of Fame, served as president/CEO of ISHOF from 2005-17.

In the 1960s, Morehouse was one of 15 Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) to sponsor varsity swimming teams. The other schools were Hampton Institute, Howard, Tennessee State University, West Virginia State College, Morgan State University, North Carolina A&T State University, North Carolina Central University, South Carolina State, Tuskegee Institute, Johnson C. Smith University, Norfolk State College, Alabama State, Southern and Virginia State.

In 1958, “the idea of black swimmers (at Morehouse) was so new, so revolutionary, that at first fans didn’t know a hot time for the 100 from a squeeze bunt,” said Coach James Haines. “Doc” Haines received his Ph.D. from Springfield College and was also the school’s director of physical education. But by the early 1960s, the student body was so wild about swimming that as many as > Morehouse College team photo—Coach Haines is pictured in the second row, far right 800 of the 1,150 students crammed into the stands to cheer on the best black swim team in the nation.

The secret to Haines’ success was having an excellent feeder system. “I stay away from the creek swimmers,” he said. “It takes competitive swimming and first-class training, and you don’t get that paddling around in creeks.”

Most of his recruits came from historically segregated programs in New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago and Detroit. But some came from mostly white programs, like junior college transfer Gerald Oliver.

“I swam for an excellent coach,” Oliver told Sports Illustrated in 1973. “A great man, but I was a hired hand. A freak. A black swimmer! At Morehouse, swimming is just an extracurricular activity, not my primary function. An all-black environment is probably just as unnatural as the whiter- > A full house as Morehouse tops Tuskegee than-white ones at the big schools, but many

THE POWER OF POSITIVE COACHING

Relationships built upon honesty, trust and communication go a long way toward cementing a bond between coach and athlete. Coupling that with knowledge of the individual first and athlete second produces a positive working relationship that can last for a lifetime.

BY MICHAEL J. STOTT

Seeing tears upon the retirement announcement of her daughter’s swim coach, the mother asked, “Why?”

“Because he understands me,” said the girl.

“For a coach, the big thing is knowing your swimmers,” says SMU coach Greg Rhodenbaugh. “My best coaching has come from listening...not any great wisdom I have.” Adds Eddie Reese, coach of 15-time men’s NCAA champion Texas Longhorns, “For a coach, there is nothing like being trusted.”

TODAY’S WORLD

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered, perhaps forever, how swim coaches conduct aquatic training. “It’s truly been a year in which every coach is struggling to make a positive impact with their swimmers in some ‘normal’ way,” says Clovis Swim Club head age group coach Mark Bennett. “This environment has changed the way most coaches operate, but not our will and desire to interject positivity into our swimmers’ days.”

THE CONUNDRUM

COVID or not, coaches will find times when it is hard to be positive. “The reason,” says senior assistant Mark Kutz at NOVA of Virginia, “is because most of us really want the kids to be better than they want to be themselves. The problem comes when we encourage them to do things they may not want to do.

“Conversely, it’s easy to be positive when working with kids who want to be good and believe you can help them. And if they believe in you, they will do almost anything for you.”

MOVING FORWARD

“As the COVID pandemic continues to change how our sport works, we coaches need to do everything we can to give swimmers a positive, meaningful experience,” Bennett avers. “We can start by observing swimmers’ behavioral practices. Veteran coaches can make an educated guess as to how it will go based on body language, eye contact, perceived enthusiasm and relating to peers. Who knows the athlete better than the coach?

“But the eye test isn’t enough,” he cautions. “When we see a swimmer struggling, mentally or emotionally, what can a coach do next?” Bennett suggests the following:

• Project positivity. Smile and greet all swimmers as they come in.

Use first names! The ability to paint a picture that swimmers are in a good place, today, might make the difference in the attitude they take into the water. Young people often mirror the behavior of decision-making adults in their lives. • Create a safe place. Swimmers should know when they enter the pool deck that they are safe to succeed, fail, to try to be themselves. Create that environment with attitude and conduct.

Monitor the attitudes and conduct of your swimmers with each other. If a coach wants swimmers to be in a place to be the best they can be, it has to be one that allows for everyone to be able to pursue excellence. • Take time to follow up. Converse with any swimmers who were struggling at the previous practice. See if they are feeling better.

If not, it’s a good time to ask if they want to talk about it or if they can take ONE positive thing to work on for the rest of practice. • Develop the connection. See how kids are doing. Ask if anyone is doing anything exciting outside of swimming, how their family members are doing or what’s coming up to which they are looking forward. • Share practice details in a positive light. Let swimmers know enthusiastically what’s planned for the day. • Look for outliers. Is anyone withdrawn from the group? Pull

“It’s truly been a year in which every coach is struggling to make a positive impact with their swimmers in some ‘normal’ way. This environment has changed the way most coaches operate, but not our will and desire to interject positivity into our swimmers’ days.” —Mark Bennett, head age group coach, Clovis Swim Club

them into the group in a comfortable way. Simply ask for some feedback about the conversation that the rest of the group may be having.

• When things aren’t going so well, be willing to adjust your

plan. Coaching is an art, more than a science. There are times when a coach needs to dig in and get the group to grind through a hard day, but if the mood of the group is intensely negative, change the practice or even have a group or team meeting to reel them in. • React to negative speech. Swimmers are going to say negative things. What we do when they do says a lot about what kind of pool deck we provide. Stay calm. Ask a swimmer what was said, why that was a comment to share and/ or ask if it’s true. Ask what can be done to turn this into a positive experience or what positive thing can be said or done to counter the negative interjection. Follow up later!

In trying to refocus a swimmer who has a consistent negative attitude, decide if it is something that needs to be discussed with the team as an expectation before more drastic (and dramatic) action takes place, like removing swimmers from practice.

Always allow a swimmer a path to return as a positive member of the team. Unless code-of-conduct rules have been broken, there should always be a place in which the swimmer can learn from mistakes and be redeemed to the team. an artful hand. One of the best at this is Weymouth (Mass.) Club coach Michael Brooks. He believes poor swims should not define the athlete or his training. His conversation begins with words like, “You and I both know that you are much better than that last swim. You’ve consistently trained well. We just need to get you to show how good you really are. That last race seemed tight and anxious, like you were thinking too much. Stop that. You know how to do this and what your race plan is. Your stroke doesn’t need any tweaking—just get on the blocks and race your guts out.”

Regarding overall meet performance, Brooks assesses what has worked well for the athlete in practice versus the meet: “This helps me tweak what we’re doing so that the next time we will be better. I have a pretty good idea of what my kids can do in races based on what I see every day.

“I might say to a swimmer, ‘I had thought that you would do a lot better this past weekend than you did.... How did you feel about your racing?... Did you think that it would be better than it was?... What do you think was going on?... Do you think the problem or problems were tactical, psychological, physiological or related to poor meet management, or something else?’

“Then we would discuss further based on the swimmer’s answers.”

IN PRACTICE

“In assessing an athlete’s overall practice performance, assuming it is not a pattern, I ask kids to ‘grade’ their practice in terms of effort, conscientiousness and performance. Sometimes one’s body just isn’t working as desired, but we can still work hard and focus on one’s skills. No one is perfect every time, but the best athletes minimize the troughs in depth and duration. I tell them, ‘Forget about this one; get a good night’s sleep and be better tomorrow.’”

If poor practice performance has been the norm, Brooks will ask his charge to review his goals, self-grade the practice effort and plan on coming back dedicated to better effort.

“I say, ‘You cannot feel satisfaction or pride when you practice sloppily, but only when you give your all. Every repeat, every set swum, gives you a chance to make yourself better—or worse. And every one affects you.

‘Don’t waste the OPPORTUNITY that you have right now. Take some time tonight after practice to write down some goals for practice sets that will help you reach those high goals you have, then come back tomorrow prepared to make them happen.’

“To be honest, “I’m more understanding in these days of COVID,” he says. “ Kids’ lives are pretty chaotic and precarious right now. It is definitely affecting their swimming, so I will cut them more slack than I used to.”

And what can be more positive—and understanding—than that?

Michael J. Stott is an ASCA Level 5 coach whose Collegiate School (Richmond, Va.) teams won nine state high school championships. A member of that school’s Athletic Hall of Fame, he is also a recipient of NISCA’s Outstanding Service Award.

> Virginia, 2021 women’s NCAA Division I champions

A NEW NO.1

For the first time in the history of the NCAA Division I Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships—since 1982—the University of Virginia finished first. It was also the first time it cracked the top 5 with its previous highest finish sixth in 2019.

BY DAN D’ADDONA AND JOHN LOHN | PHOTOS BY NCAA MEDIA

THE TOP 10 1. VIRGINIA..................................491.0 2. N.C. STATE...............................354.0 3. TEXAS......................................344.5 4.CAL..........................................290.0 5.ALABAMA...............................266.0 6.MICHIGAN..............................224.5 7. OHIO STATE...........................215.5 8.GEORGIA................................181.0 9. STANFORD..............................159.0 10. TENNESSEE..........................153.0

VIRGINIA’S ROAD TO HISTORY

BY DAN D’ADDONA

It was a long time coming for both the University of Virginia and the ACC, leading to a first-time NCAA championship for the school and the conference.

Virginia’s youth movement tipped the balance of power in swimming to the ACC for the first time as the Cavaliers became the first NCAA champion ever from the conference.

Coach Todd DeSorbo’s team thought it was going to happen last year, but the pandemic forced a year’s delay.

“Having it taken away last year was pretty heartbreaking,” said Virginia senior Paige Madden. “At the same time, it fueled a fire in all of us, and that is what led to our success this year. We had a point to prove, and I think we did that, which is exciting.”

Virginia led the NCAA Division I Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships, March 17-20, at Greensboro, N.C. from start to finish. The Cavaliers scored 491 points, a 137-point margin of victory over runner-up North Carolina State (354).

The goal was clear all season, and the Cavaliers did everything they could to make it happen.

“It is just such a great feeling,” said Virginia’s Kate Douglass. “I feel like we have all been waiting for this to happen for a long time.

LOOKING AHEAD With Madden graduating, there will be a hole to fill, but Alex Walsh’s sister, Gretchen, will be on campus next year, with huge point-scoring ability. “I get to train with Paige every day,” > Virginia had three individual-event champions: Paige Madden (200-500-1650), Alex Walsh (200 IM) and Kate said Walsh. “I love it. (Our seniors) have Douglass (50 free). Douglass (pictured) also added runner-up finishes in six other events: 100 free, 100 fly plus the great leadership—they stayed this year, 200-400 medley and 200-400 freestyle relays. Both of her freestyle anchor legs on the medley relays were the fastest and that meant the world to me. They are splits of all the swimmers, as were her leadoff legs on the freestyle relays. something that drew me to Virginia,” Walsh said. “This played a big factor with me We have made so many sacrifices this year, and all of us worked so coming (here). I just wanted to be a part of hard that we all deserve this. this team because of the connection I had with them. Watching their

“We have so many fast swimmers on this team—it is an elite momentum go from ninth at NCAAs to sixth, then last year seeded training group. We get to train with some of the best swimmers in to win...then this year, we win! That whole trend upward and going the country every day. I don’t know if it has sunk in yet. It is crazy for the title was something I really wanted to be a part of. It makes that we are the first ACC team to win a national title.” the team bond extra strong.” The Cavaliers aren’t going anywhere. Next year could be the TOTAL DOMINANCE most anticipated showdown in history as the powerful Virginia

The dominance started with the 800 yard freestyle relay win on budding dynasty will face a rebooted Stanford team that will include opening night (6:52.56 with Kyla Valls, Madden, Ella Nelson and world record holder Regan Smith, top high school swimmer and Alex Walsh). It was a promising start, but only the beginning. NAG record holder Torri Huske and the likely return of Olympian

On Day 2, the Cavaliers made a statement as Madden won the Taylor Ruck, who took this year off as an Olympic redshirt. 500 free (4:33.61), Walsh won the 200 IM (1:54.62) and Douglass That will be two of the youngest and most talented teams getting won the 50 free (21.13). after it where every hundredth of a second will have a chance to

Madden won the 200 free (1:42.35) on Day 3 when the Cavaliers decide the entire national championship. made their depth show, building a 103-point lead over NC State But that is something for next year’s team to think about. This without winning any other event. year’s Virginia team overcame missing what was supposed to be

On the final night, Madden won the 1650 (15:41.86), and the their breakout year, then quickly proved they were the best team in Cavaliers continued their high rankings in the relays. After their the country. opening-night win in the 800 free relay, Virginia put together four Yes, it was the first championship for Virginia and the Atlantic straight second-place finishes. Coast Conference...but it won’t be the last!

“It is so sweet. I am really excited,” Madden said. “I teared up on Editor’s Note: See pages 40-41 for a story about Virginia’s the last relay. It was just really special having the entire team here Paige Madden, showing special sets from her age group/club coach, with us. It is incredible and hasn’t hit me yet fully, but it is amazing. Greg Davis.

“We had to load the van, and a lot of girls had trouble loading the trophies in our suitcases, so we had to load them in Panera bags. I really just wanted to have fun, and this is the cherry on top.” NC STATE ADDS TO ACC DOMINANCE A TWO-YEAR MISSION

This is what Virginia hoped to accomplish last year before the pandemic shut down the season right before the NCAA Championships. It added some extra motivation for the Cavaliers, something Coach Todd DeSorbo saw all season from his swimmers.

“The women have been on a mission for two years since the 2019 NCAAs (when they placed sixth with 188 points), and they performed at a really high level all week,” he said.

“It is a really exciting time for our program and our conference. It has been a challenging year to say the least for everybody. I am in awe of our women and their discipline and their commitment to COVID-19 protocols and staying healthy on top of training at an elite level. I could not have asked for anything more. I am really at a loss for words at what they accomplished this year.”

It wasn’t just the individual stars or the relays. The Cavaliers put at least one swimmer in the final of every swimming event. “That was a personal goal as a coach that I had for the program, which I did not share with the women until after Friday’s finals. Putting someone in the A-final in every single (swimming) event is pretty impressive, and it shows our overall depth. It takes a full team to win a national title, and these ladies brought it every minute of every day,” DeSorbo said.

BY DAN D’ADDONA

The Atlantic Coast Conference never had a school win the women’s NCAA Division I team title. But Virginia took care of that.

So, it goes without saying that the ACC never had any of its member schools finish 1-2 at the meet. But that all changed in 2021 when North Carolina State placed runner-up to help supplant the Pac-12 Conference as the current women’s swimming powerhouse.

Prior to this season, teams from the Pac-12 (previously Pac-10 through 2011) had placed either first or second in 29 of the 38 meets since the NCAA first held its championships in 1982. And it boasted five 1-2 finishes, including the previous three years with Stanford and Cal.

ALL IN THE FAMILY

This year’s Wolfpack squad was led by some familiar names in the sport of swimming, as new contenders in extremely talented

fastest performer in history.

“It felt so good. I was waiting to do that for so long. It has been a goal for a really long time now,” Berkoff said. “It is fun to do it, but really fun when you have stiff competition. That makes it even better.”

Hansson is the younger sister of former USC swimmer, Louise, a multi-NCAA champion who had previously set the NCAA record in the 100 butterfly in 2019. Both sisters competed for Sweden at the 2016 Olympics in Rio.

“Being a part of a family like this is a positive thing,” Sophie said. “My sister and I don’t race the same events and don’t really have to compete against each other. People outside compare us more than we do. But it is really cool that I got to win my own individual championship. I am really happy about it.”

Sophie won the 100 breaststroke in 57.23, tying for third fastest all-time with Breeja Larson, behind Lilly King and Molly Hannis. She also won the 200 breast (2:03.86).

“It felt amazing,” Hansson said. “I felt strong from the start and I just wanted to go out a little faster than this morning, and bring it home. I am really competitive, and the last turn heading into the last 25, all I am thinking is to get those hands to the wall. I am tall and I have long hands, and I just have to get them to the wall.” * * *

> NC State’s Katharine Berkoff (top) and Sophie Hansson combined for three individual event wins along with two relay titles, including an NCAA/U.S. Open/meet record in the 400 medley relay. Before this season, the Wolfpack had only one event title in team history. Both NC State swimmers also teamed up with Kylee Alons (butterfly) and Julia swimming families made their mark on the national stage— Poole (freestyle) to set an NCAA/U.S. specifically, Katharine Berkoff and Sophie Hansson. Open/meet record in the 400 medley relay (3:24.59), bettering

While being a part of elite families can cast a shadow and Stanford’s 3:25.09 from 2018. provide added stress, both Berkoff and Hansson said they don’t feel Berkoff, Hansson and Alons (freestyle) later joined Sierra Rowe any pressure from within the family. Instead, they use the support of (butterfly) for another relay victory, clocking 1:33.18 in the 200 their fast families to strive for bigger goals. medley, just 7-hundredths off Stanford’s NCAA/meet record.

Berkoff’s father, David, was an NCAA champion in the 100 The Wolfpack ended up winning five events, quite an backstroke for Harvard in 1987 and 1989, sandwiched around a year accomplishment considering NC State previously had only one in which he was a member of the U.S. Olympic team. event title in team history.

“I think it is pretty fun,” Katharine said. “I think the reason I With very few seniors on the squad, this year’s meet provided have always had such high goals in swimming is because of my a huge statement for NC State as well as for Berkoff and Hansson, dad. I always knew I wanted to do what he did. It has been more who are building their own legacy as leaders of the Wolfpack. motivating than anything. It is so special to win one for myself and for my team. I am so grateful for my support system. “It is pretty cool that (my dad and I) won the same event. I know THE TALK OF THE MEET my dad was really excited about it. We would compare his times in BY JOHN LOHN college versus mine, and we were pretty close. He got a lot faster, obviously, but it is so special (to have that bond).” Barrier-breaking performances are long remembered in the sport. Sure, some are recalled with greater prestige than others,

Katharine was a World University Games gold medalist for notably Jim Montgomery cracking the 50-second mark in the 100 Team USA in the 100 back, but has now taken the next step with her meter freestyle and Natalie Coughlin becoming the first woman to first NCAA title. And she is only a sophomore, actually competing go sub-minute in the 100 meter backstroke. in her first NCAA Championships because of last year’s meet being But anytime an athlete breaches a numerical threshold, the effort canceled. is special.

She won the 100 yard backstroke in 49.74 to become the fourth- So, when Maggie MacNeil used her considerable talent to go

> Michigan’s Maggie MacNeil claimed individual titles in the 100 fly and 100 free and was the runner-up in the 50 free. With her 100 fly win, she became the first woman to break the 49-second barrier with her 48.89. Not surprising, she was named CSCAA Division I Swimmer of the Year.

where no woman had gone before in the 100 yard butterfly, there was plenty of appreciation for the achievement.

Representing the University of Michigan at the women’s NCAAs, MacNeil was the showstopper of the competition. She claimed individual titles in the 100 butterfly and 100 freestyle and was the runner-up in the 50 freestyle. Not surprising, she was named CSCAA Division I Swimmer of the Year.

Yet, what she did in the 100 fly was the talk of the meet.

A DELAYED OPPORTUNITY

In early 2020, hype was brewing about the impending NCAA showdown between MacNeil, USC’s Louise Hansson and Tennessee’s Erika Brown in the 100 fly. There was considerable speculation that one of those women—and perhaps all—would dip under 49 seconds. Of course, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, that much-anticipated clash was canceled.

While Hansson and Brown moved on from the collegiate ranks, MacNeil took advantage of another opportunity. On the third night of this year’s Championships, MacNeil blasted a time of 48.89 to etch herself as the inaugural female member of the sub-49 club. Coupled with her 49.76 clocking in the 100 backstroke as part of Michigan’s 400 medley relay, MacNeil joined rising American star Regan Smith as the only women to own sub-50 performances in both the 100 fly and 100 back.

“I was definitely not (expecting to go that fast),” MacNeil said. “It has been a goal of mine for a while, so it was amazing to achieve that, especially at NCAAs. Not having NCAAs (last year) kind of fueled the fire in me.”

In addition to her barrier-busting butterfly, MacNeil won the 100 freestyle in 46.02 to just miss becoming the third female in history to go 45-point. She added silver in the 50 free in 21.17, just 4-hundredths shy of the winning time produced by Kate Douglass of Virginia. Douglass was the runner-up to MacNeil in the 100 fly and 100 free, and their three-round tussle was a highlight of the meet.

FIGHTING THROUGH ADVERSITY

The fact that MacNeil was able to deliver the best times of her career at NCAAs was no easy feat. The COVID-19 pandemic derailed Michigan athletes for several weeks during the season, forcing athletes out of the water. When practice resumed, they had to make up for lost time. Obviously, MacNeil demonstrated the ability to fight through adversity.

If MacNeil was shocked by her speed in the butterfly, others were not. The Canadian star has been a known commodity for several years, her breakthrough arriving at the 2019 World Championships. It was in Gwangju, South Korea where MacNeil pulled off an epic upset of Sweden’s Sarah Sjostrom to win gold in the 100 meter butterfly. Since that time, the junior has checked in with a multitude of swift performances for the Wolverines, regardless of the impact of the pandemic.

NEXT UP

MacNeil now awaits this summer’s Olympic Games in Tokyo, where she will have the chance to back up her world title by capturing the biggest prize available in the sport. Depending on how Sjostrom recovers from a fractured elbow suffered earlier this year, MacNeil might head into the Olympics as the favorite. Meanwhile, she is expected to be a key link on medal-contending Canadian relays.

Following the Olympic Games, MacNeil will return to Ann Arbor and her senior season at Michigan. Of course, she’ll chase repeats of her NCAA crowns in the 100 fly and 100 free. And, maybe, she’ll threaten another barrier. Heck, she’s done it once, and that makes Maggie MacNeil a part of history. SW TOTAL ACCESS

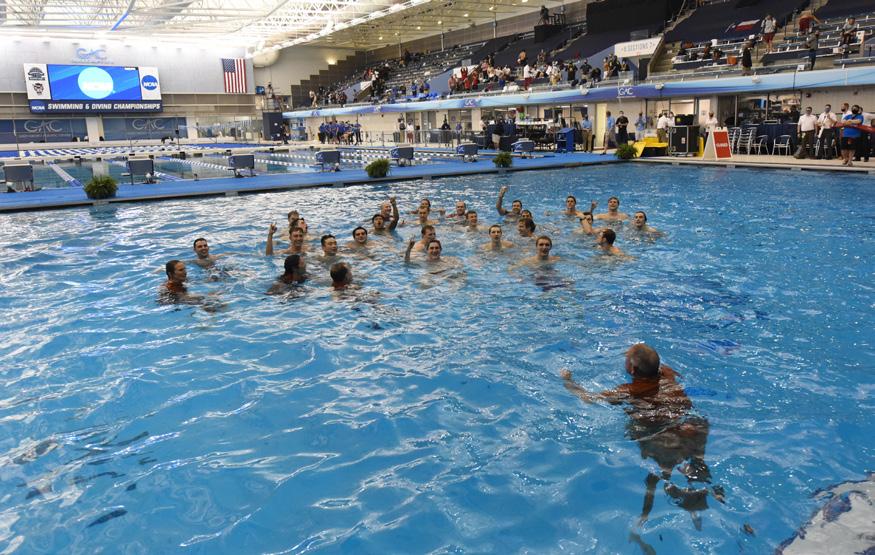

> Texas, 2021 men’s NCAA Division I champions

THE PERFECT RETIREMENT GIFT

Days before their coach, Eddie Reese, officially announced his retirement from coaching after 43 years, the Texas men’s team won their 15th men’s NCAA national team championship.

BY ANDY ROSS AND JOHN LOHN | PHOTOS BY NCAA MEDIA

THE TOP 10 1.TEXAS......................................595.0 2. CAL..........................................568.0 3. FLORIDA..................................367.0 4. GEORGIA................................268.0 5. LOUISVILLE.............................211.0 6. INDIANA ................................207.0 7. OHIO STATE.............................180.0 8. N.C. STATE...............................164.0 9. VIRGINIA..................................152.0 10. TEXAS A&M..........................151.0

THIS ONE’S FOR EDDIE!

BY ANDY ROSS

2020 was expected to be one of the tightest NCAA meets in recent history. After Cal won the 2019 team title in Texas’ home pool, ending the Longhorns’ four-year winning streak, Texas put the beatdown on the reigning champs at the Minnesota Invite in December 2019. That set up a grudge match for March 2020 in Indianapolis. But COVID-19 took away that opportunity for both teams, putting the rivalry on pause.

With all the challenges the pandemic provided this past year, the fact that many of the best swimmers were able to convene in Greensboro, N.C. for NCAAs, March 24-27, was a win in itself.

After analyzing the psych sheet, Texas and Cal knew that every point would matter in determining the champion.

EARLY MOMENTUM

Texas came out swinging on the first day with Drew Kibler, Austin Katz, Carson Foster and Jake Sannem winning the 800 yard free relay (6:07.25), but the next day belonged to Cal. Bjorn Seeliger, Ryan Hoffer, Daniel Carr and Nate Biondi came within 28-hundredths of the NCAA/meet/U.S. open record in the 200 yard freestyle relay (1:14.36), and Hoffer repeated his title in the 50 free

> Texas divers outscored team runner-up Cal 83-0, with Jordan Windle leading the way with 52 points, winning the 1-meter and placing second in 3-meter and fourth on platform.

in a 1-2 finish with Seeliger (18.33-18.71). In the 500, Trenton Julian and Sean Grieshop each reached the A-final (4th, 7th), then Hugo Gonzalez and Destin Lasco went 2-3 in the 200 IM.

Cal seemed to have all of the momentum, as the Bears built a 71-point lead heading into second day’s final two events. But Texas first responded with Jordan Windle and Noah Duperre, who went 1-2 in the 1-meter (435.60-405.45), cutting the deficit to 33 points. The Longhorns’ Chris Staka, Caspar Corbeau, Alvin Jiang and Daniel Krueger followed by beating Cal in the 400 medley relay (3:00.23-3:00.73), closing the margin to 27 heading into the meet’s third day.

TEXAS MAKES ITS MOVE

And that’s when the Longhorns took off.

First came the 400 IM, with Texas, led by Carson and Jake Foster making their long-awaited NCAA debuts, placing second and fifth, with Braden Vines and David Johnston following in sixth and eighth. It was the first time a Division I men’s team had that many swimmers in the A-final of an event since the Longhorns put up a mind-boggling six of eight in the 100 fly in 2015.

In just one event, Texas had erased its deficit to lead by 3 points— and the team never trailed the rest of the meet.

Interestingly, Coach Reese’s charges didn't win an individual swimming event—the first national championship-winning team to do so since Auburn in 2006. Their only victories came in the 800 free relay on the first day and back-to-back wins on the second day: 1-meter diving and 400 medley relay.

On the other hand, their depth was on full display. Not only did Texas have an A-finalist in every single event, every single swimmer and diver scored a point—a testament to the team effort.

“Once the momentum starts, people see that if he can do it, I can do it,” said Kibler. “We saw that with every single person on our team, swimmers and divers. Anything you can give, we will take... and that brings out the best in people.”

Carson Foster added, “We had to leave guys home to hit the roster limit of this meet. We had 10 swimmers get left home, which shows how deep we are, but they very well could have come and scored, too. It is huge that we scored all 20 guys (plus four divers), but we could have had all 30 of us score. We had guys in every single final. We just fit together like a puzzle.

“The reason why you come to Texas is to win championships like this.” DIVING WAS THE DIFFERENCE

Texas’ divers also played an important role in helping the Longhorns win the team championship. Windle made all three A-finals. In addition to his 1-meter title, he placed second in 3-meter and fourth in platform. Duperre added 23 points on springboard, Andrew Harness scored seven, and Brendan McCourt scored one point, giving Texas 83 total points in diving...to Cal’s zero!

In fact, it could be said that the diving events proved to be the difference in determining this year’s national champion. With their divers, Texas won the meet by 27 points; without, the Longhorns would have finished second, 56 points behind the Bears.

“It meant everything,” said Windle. “Like the name suggests, it is swimming AND diving, and our team has a very diverse set of skills. We support each other all the way.”

ALL OVER BUT THE SHOUTING

Heading into the fourth and final day, Texas held a 42-point lead over Cal, and the team placed enough bodies in A-finals to seal their national title.

Johnston placed seventh in the 1650. Katz and Carson Foster were fifth and sixth in the 200 back. Kibler and Krueger tied for second in the 100 free. Corbeau was fourth in the 200 breast, and Sam Pomajevich was sixth in the 200 fly.

With Windle’s fourth-place finish on platform, Texas led by 37 points going into the meet’s final event, the 400 free relay. Even with a Cal victory in the relay—which it accomplished (2:46.60 with Seeliger, Hoffer, Lasco and Gonzalez)—all Texas had to do was make sure all four swimmers had safe starts. They did, and their fourth-place finish was enough for the team title.

GREATEST COACH OF ALL TIME

The national championship was the 15th for Texas, all coming under Coach Eddie Reese.

Two days after the meet was over, Reese announced his retirement, closing the door on one of the most successful coaching careers for anyone in the sport of swimming and the entire landscape of college sports.

Reese’s 15 national titles are the most for any coach in NCAA Division I men’s swimming—four more than Ohio State’s Mike Peppe, who won 11 titles from 1943-62...and three more than Michigan’s 12 titles under four different coaches between 1937 and 2013.

Also, the Longhorns’ 595 points are the most scored at men’s NCAAs since Auburn’s 2004 team scored 634.

“Simply put, Eddie Reese is the greatest coach of all time,” Texas’ Carson Foster said. “If it was ever debated before, it is over now. You can’t argue with 15 national championships in five different decades.

“He and all of our assistants do an incredible job with recruiting, but also with developing the swimmers. They have also created such a culture with the team, where there is not a single person who is complacent with anything but a championship—and that is the culture from Day 1. We don’t accept anything less.

“Forty years after he won his first, he won his 15th...and that is beyond special for all of us and the Texas alums.”

SCINTILLATING PERFORMANCES

BY JOHN LOHN

One has been tabbed as a future star for the United States, a backstroke sensation who can venture into several other events. The other guy is more of an unknown when it comes to international potential, but his presence on the collegiate stage rattled the aquatic Richter Scale.

When the NCAA Men’s Championships unfolded in late March, the 15th team title for the University of Texas was the major headline. But on an individual basis, all eyes were on the efforts of Texas A&M’s Shaine Casas and Cal’s Ryan Hoffer, who went a combined 6-for-6 in solo events and produced some scintillating performances.

> Despite all the hype and pressure placed on Shaine Casas’ shoulders, the Texas A&M junior responded by tripling at NCAAs. “I fell back on my support system, and I did it for them. I am so happy that it worked out this way.”

> Ryan Hoffer capped off his senior year at Cal with titles in the 50-100 free and 100 fly, with all of his swims among the fastest of all-time.

CASAS EXCEEDS EXPECTATIONS

Although the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the sport over the past year, one thing the coronavirus could not stop was the hype surrounding Casas. He is a young gun who has been pegged for stardom, some suggesting the ultimate success attainable in the sport: Olympic gold. At NCAAs, the junior lived up to the vast expectations thrust upon him by winning the 100 yard backstroke, 200 backstroke and 200 individual medley.

In the 200 back, Casas established himself as the No. 2 performer in event history, a clocking of 1:35.75 lighting up the scoreboard and necessary to fend off Cal’s freshman standout, Destin Lasco (1:35.99). Meanwhile, he dropped winning times of 44.20 in the 100 back and 1:39.53 in the 200 medley.

An athlete tripling at the NCAA days, and he capped his senior year at Cal with a dominant showing: Championships is a spectacular achievement. But considering Casas was hindered by internal struggles in the weeks leading into the competition, his showing was even more awe-inspiring. Titles in the 50 freestyle, 100 freestyle and 100 butterfly, all three crowns ranking Hoffer among the fastest of all-time.

“The pressure was incredible. It almost cracked me,” Casas said The efforts, however, did not come without a bit of anxiety. on the final night of NCAAs. “I was not going to come to this meet, “I definitely learned how to manage (my nerves),” Hoffer said. but my mom was there for me, and my friends and coaches inspired “I almost look forward to the nerves because I feel like it gives me me and supported me to push through and keep going. I am very that extra pop where I need something more. It is that fuzzy feeling happy that I did. going into the water. It is what makes the race, the race. It makes a

“After SECs, I felt like I cracked a little. The pressure and good race feel that much better.” everything going on with me was just too much. I felt like I had, With Hoffer leading the way, Cal also secured a pair of relay not mental health issues, but too many things going on—dealing titles and finished second to Texas in the team standings. For a guy with too much. But I fell back on my support system, and I did it for who arrived on campus surrounded by hoopla, he certainly delivered them. I am so happy that it worked out this way.” during his senior campaign.

Now, Casas will try to carry his collegiate momentum to the The big question is simple: Can Hoffer translate his short-course big pool, specifically the United States Olympic Trials. While the United States is stacked in the backstroke events, Casas will be among the favorites to earn an invitation to this summer’s Olympic success to the 50-meter pool, where Olympic berths are doled out? Because of the pandemic, we haven’t seen what Hoffer is capable Games in Tokyo. of in the Olympic pool in some time. Perhaps this summer is his moment to break out and emerge as someone who can benefit Team DOMINANT SHOWING FOR HOFFER USA on the international stage.

What about Hoffer? Regardless of what happens with Casas and Hoffer this summer,

Well, that answer is a little more difficult to decipher. Hoffer has their appearances at the 2021 NCAA Championships won’t soon been an extraordinary short-course swimmer since his high school be forgotten.

> Max McHugh became the first swimmer from the University of Minnesota since 1996 to win a men’s NCAA title when he clocked 50.18 in the 100 yard breast (fourth fastest all-time). He added a victory the next day in the 200 breast with a 1:59.02 (fifth fastest all-time). > After winning the 200 fly, Louisville’s Nick Albiero admitted, “(My dad—Coach Arthur Albiero—and I) are both pretty emotional guys, and we gave each other a hug, and the tears were coming down,” he said. “I’m so grateful he is on this journey with me and that we get to do it together.”

PATIENCE REWARDED

BY ANDY ROSS

At last! After missing an opportunity for a breakout 2020, Minnesota’s Max McHugh and Louisville’s Nick Albiero backed up the hype with individual NCAA titles in 2021.

The cancellation of the 2020 NCAA Championships was devastating for all 235 swimmers who had qualified for the meet. But for the top seeds on the psych sheet, it was especially devastating, knowing they would have to wait 12 more months for the chance to compete again. So getting the chance to race at this year’s meet was especially gratifying.

For guys like McHugh and Albiero who both have family ties to their schools—McHugh is following in the footsteps of his older brother, Conner, and Albiero swims for his dad, Arthur—their wins this year meant that much more.

McHugh won the 100 and 200 breaststroke (50.18, 1:49.02), which was Minnesota’s first ever NCAA title on the men’s side since 1996, while Albiero won the 200 butterfly (1:38.64) and swam on the winning 200 medley relay team (1:22.11/20.07 butterfly split).

McHUGH: FOR THE PROGRAM AND FOR HIS BROTHER

“Man, it means everything that I could do it for the program and for my brother,” McHugh said after winning the 100 breast. “(Conner) has been my training partner for 12 years. It’s something special for the program and for my family. It has been my goal all along. I haven’t realized what I have done just yet, but it will be good once I get home and get to show them the trophy.

“I made sure to FaceTime my family after I warmed down. It means a lot to me, but it means just as much to them as well, so I’m glad I got to bring it home for Minnesota.” McHugh had been the heavy favorite in the 100 breast, and he delivered by nearly becoming the second man to break 50 seconds from a flat start. But it was in the 200 where he turned heads by taking down Cal’s Reece Whitley, who entered the meet as the second fastest performer all-time (1:48.53) and seemed ready to take a run at Will Licon’s NCAA/meet/American/U.S. Open record of 1:47.91.

But McHugh took it out with Whitley, and the pair were stroke for stroke on the final 50, with McHugh edging out his rival by 52-hundredths.

“(Reece) pushes me every day in practice,” McHugh said. “It’s awesome. He’s an awesome competitor. I think we both push each other, and it is always nice to race him.”

AN EMOTIONAL WIN FOR ALBIERO

Albiero was among the favorites to win the 200 fly in a field that included Cal’s Trenton Julian, Texas’ Sam Pomajevich, Georgia’s duo of Camden Murphy and Luca Urlando, and Indiana’s Brendan Burns, who all looked to be a factor in the event.

Albiero cruised through the prelims with the top seed and remained unfazed when Julian took it out fast in the lane next to him in finals, holding nearly a second lead. At the 150, Julian was 7-tenths ahead of Albiero, and held that lead through the 175 turn. Albiero kicked underwater about halfway and popped up right with Julian, utilizing the momentum of the turn to pull ahead and maintain the lead.

“I specifically work on underwaters every day,” Albiero said. “It’s in our warm-up and in our main set, and that’s what I really utilize, especially for short course. I knew I was going to have a chance if I kept within striking distance at the 150 and 175. I just put my head down and hoped for the best.

“After the race, I pretty much started crying. (My dad and I) are both pretty emotional guys, and we gave each other a hug, and the tears were coming down. It means everything to have him on deck. He knows my swimming better than I do. He knows me better than I know myself, and I’m so grateful he is on this journey with me and that we get to do it together.”

Albiero became just the third male swimmer from Louisville to win a national title. The school began commemorating its national champions on the wall of its home pool in 2012 when Carlos Almeida won the team’s first title. Albiero, who has been swimming in that facility for as long as he can remember, knows the legacy he is joining.

“It means everything,” he said. “I see those names—Carlos Almeida and Joao de Lucca—every day when I’m swimming at practice. They’ve motivated me when I got to watch their careers... and even the females, Kelsi (Worrell) and Mallory (Comerford)— they inspired me, too. To be able to join that group is amazing, and I’m so honored to be a part of that.”

SW TOTAL ACCESS

SOME THINGS NEVER SEEM TO CHANGE

A year into the pandemic that has completely changed our world, Queens University of Charlotte brought about some stability to the 2021 NCAA Division II Swimming and Diving Championships by sweeping their sixth straight women’s and men’s team titles.

The 2020 NCAA Division II Championships BY ANDY ROSS also had the upper hand in wins—8-3, including a were cut short after just three sessions due to the tie between Kunert and Ostrowski in the 200 free COVID-19 pandemic affecting the entire world. A (1:33.29). year later, March 17-20, at Birmingham, Ala., the only concern was Kunert also came up big for Queens in winning the 200 fly a tornado threat after the first session of prelims that delayed the first (1:42.85) and anchoring the fastest 800 free relay (6:22.59) with night of finals by 18 hours, turning the second day of competition teammates Balazs Berecz, Skyler Cook-Weeks and Luke Erwee. into a timed finals session. Following a win in the 200 back by Nathan Bighetti (1:43.51),

But one thing remained constant: Queens University of Charlotte Drury was within 25 points of Queens with three events to go. But (N.C.) celebrated another team championship for both its women’s the Royals shut out Drury in the 200 breast by 27 points, placing and men’s teams. It only took them five years after starting their fourth and seventh, then withstood a 16-0 advantage by Drury in swimming program to win their first title in 2015. And neither team 1-meter diving and a 6-point margin (2:50.98 to 2:52.28) in the 400 has lost at NCAAs since. free relay to win the meet by 30 points.

MEN’S RACE: QUEENS 561, DRURY 531, INDIANAPOLIS 369

Day 1 finals brought two Division II records, with Drury (Nathan Bighetti, Dawid Nowodworski, Dominik Karacic and Alexander Bowen) opening the men’s competition with a 1:24.69 in the 200 yard medley relay, breaking Queens’ 1:24.83 from 2018.

The very next event saw McKendree’s Fabio Dalu set an NCAA record in the 1000 (8:54.10), lowering Queens’ Alex Kunert’s 8:56.76 record from 2019. Dalu, who was named the CSCAA Swimmer of the Year, also broke his own NCAA 14:55.42 record in the 1650 from earlier this season with a 14:55.12.

Drury’s Karol Ostrowski nearly became the third record breaker of the night, missing his own 50 free mark of 19.08 with a 19.12. But in his second chance of the day, leading off the 200 free relay, Ostrowski clocked 18.92 to become the first man outside of NCAA D-I to break the 19-second barrier. His teammates (Kham Glass, Caleb Carlson and Alexander Bowen) followed with another record at 1:16.90, erasing Tampa’s 1:17.27 from 2016.

Ostrowski returned on the final night with a record in the 100 freestyle (41.25) that would have placed second at the Division I meet. He then anchored Drury’s winning 400 free relay with a 41.10, one of four relay wins for the Panthers.

Drury actually held the lead through six events before Queens had four guys score in the top eight of the 400 IM (4th-5th-7th8th), giving them a lead they would never relinquish. The Panthers WOMEN’S RACE: QUEENS 695, DRURY 441, INDIANAPOLIS 391

Queens dominated, winning by 254 points—the third straight year (and fourth of the last six) that the Royals have won by triple digits.

A large part of their success came from sophomore Danielle Melilli, who was named the CSCAA Swimmer of the Year for her wins in the 50 free (22.57) and 100 breast (1:01.32). She also finished second in the 100 free (49.50) to teammate Lexie Baker (49.49) and fourth in the 200 free (1:49.70), while swimming on both of Queens’ winning medley relays (1:40.13, 3:38.00).

Indianapolis won both sprint free relays (1:30.92, 3:19.98) en route to a program-high third-place finish. The Greyhounds also celebrated their first women’s national champions, with Marizel van Jaarsveld winning the 200 IM (1:57.84) and Kaitlyn McCoy taking the 200 back (1:56.39).

Queens used its impressive depth to win the team championship, as only Melilli, Baker, Giulia Grasso (500 free, 4:48.80) and Francesca Bains (1650, 16:30.98) took home individual titles. Drury put up a fight with individual wins from Allison Weber (1000, 9:53.12), Laura Pareja (100 back, 52.98) and two from Bec Cross (400 IM, 4:14.19; 200 breast, 2:13.59), giving the Panthers four straight runner-up finishes and five in the last six years after they had won six of the previous eight NCAA D-II team titles.

> PICTURED ABOVE Queens University of Charlotte (N.C.) won the men’s competition at the NCAA Division II Championships by 30 points in a close battle with Drury. Both the Royals’ men’s and women’s teams won their sixth straight title. SW TOTAL ACCESS

NO LIMITS!

Claire Curzan has been swimming fast since she was a young age grouper and has continued to do so in high school. Last March, she came within 13-hundredths of the American record in the short course 100 fly, and in April, she found herself within 22-hundredths of the long course U.S. best. She’s versatile, she’s coachable, she has international experience, and she’s moved from a fringe Olympic contender to an Olympic favorite. Curzan is only 16, and her promising future couldn’t be brighter.

BY DAVID RIEDER

For years, Claire Curzan has been recognized as one of the most impressive young swimmers in the country. She has been consistently setting national age group records in butterfly, backstroke and freestyle events since she was 12, and in the summer of 2019, she earned some acclaim by finishing second in the 100 meter back and fifth in the 100 fly at U.S. Nationals. At the World Junior Championships a few weeks later, Curzan won four medals: silver in the 100 back, bronze in the 50 fly and 100 fly and gold on the U.S. women’s 400 medley relay.

In February 2020, Curzan broke a pair of national high school records in the 100 yard fly and 100 back while representing Cardinal Gibbons High School at North Carolina’s high school state championships. She was a high school sophomore at that point, only 15.

Anyone who has followed Curzan’s career could see her special potential quite clearly, but then the COVID-19 hiatus came and competition came to a halt. As soon as Curzan returned to competition, she was already one of the best sprint butterflyers in the world.

At a July 2020 intrasquad meet, Curzan’s first competitive foray in four months, she swam a 50.03 in the short course 100 fly, making her the eighth-fastest swimmer in history. A few weeks later, she swam under 50 seconds for the first time. By March 2021, Curzan had nearly taken down the American record. She swam a 49.51, just off Erika Brown’s record of 49.38, and good for fifth-fastest all-time in the event.

SHE CAN SWIM LONG COURSE, TOO

Well, sure, that’s just short course yards, but over the course of several months, Curzan rapidly proved herself in the big pool, too.

Pre-COVID, her 100 meter fly best time was 57.87, but in the fall of 2020, she dropped to 57.57 and then, at the U.S. Open in November, to 56.61. Suddenly, the 16-year-old had vaulted herself into a three-way tie for 12th-fastest all-time in the 100 fly, sharing that spot with the likes of 2000 Olympic gold medalist Inge de Bruijn, and third-fastest ever among Americans behind only 2012 Olympic gold medalist Dana Vollmer and 2016 Olympian Kelsi Dahlia. It was the fastest time any American swimmer had posted since 2018.

[PHOTO BY PETER H. BICK]

“The whole week of training before, I wasn’t really feeling that great in the water,” Curzan said. “I felt kind of heavy, and then in warm-up, my fly felt amazing. I didn’t know I was taking it out as fast as I did. I was just kind of sticking to my race plan and just going off the adrenaline,” Curzan said. “I was just kind of shocked. A little tinkling in the back of my head told me that I could go that fast, but I didn’t really believe it until I looked up and saw it. It was just one of those races where it’s kind of out-of-body.”

But Curzan was not done showing her cards quite yet. In April, while racing against fellow teenage star Torri Huske in the 100 fly at a meet in her home pool in Cary, N.C., Curzan dropped her best time to a stunning 56.20, a performance that reverberated around the swimming world. She moved to eighth all-time in the event and became the second-fastest American ever, ahead of Dahlia.

“I thought I could go 56, 56-mid or high. I don’t know. I was not expecting that,” Curzan said. The immediate aftermath of the swim left Curzan in a state of almost shock, and it took a little while for the impact of her effort to sink in. “I didn’t know I could go that fast. I didn’t know I could drop that much again.”

With just a few quick performances, the Olympics had become much more than a dream. Now, Curzan will go to June’s U.S. Olympic Trials firmly in the spotlight. Her best time is now just 2-tenths off Vollmer’s American record (55.98), and having dropped more than a second in the last year, it’s not crazy to think she could make that leap. She has already swum quicker than the silver medalwinning time from the 2019 World Championships.

And, yeah, she’s still just 16 years old!

THE COACH’S PERSPECTIVE

At the TAC Titans, Curzan’s coach is Bruce Marchionda, and Curzan remembers Marchionda telling her after the Greensboro meet “how I don’t have to go that much faster to make the Olympic team.”

“Her workouts leading up to that swim indicated that she could go that fast,” Marchionda said. “Whether she would or not, I had no idea, but based on her workouts, I knew that was definitely a possibility. For her, when she did, that gave her confidence in what we are doing and belief in the system that we have put in place for all of our swimmers, not just her. I say, kind of jokingly, the negative

[PHOTO BY CONNOR TRIMBLE ]

> In the summer of 2019, Curzan finished second in the 100 meter back and fifth in the 100 fly at U.S. Nationals as a 15-year-old. She’ll turn 17 on June 30, two days after the end of the U.S. Olympic Trials.

of that is it does put a lot of pressure on someone.” Marchionda called Curzan “probably one of the most coachable athletes that I’ve coached in the last 30 years.” He complimented the 16-year-old’s ability to take feedback and make stroke changes, including in her head position while breathing in butterfly. She consistently brings a positive attitude and competitiveness to practices that benefits the entire group.

“Ninety-nine percent of the time, she shows up with a smile on her face and maintains that smile throughout the workout,” Marchionda said.

In practice, Curzan likes working her underwaters, already a strength of hers, and she enjoys opportunities for off-the-blocks allout efforts. Long, aerobic swimming and repeated fast efforts on short rest, on the other hand, are not her favorite. Right before sets that she is not thrilled about, Curzan “will look at you with those sad, puppy-dog eyes, like, ‘I have to do this?’” Marchionda said. “And then she’ll turn around and do it...and crush it.”

One resource Curzan has available to her is Claire Donahue, a 2012 Olympian in the 100 fly who Marchionda coached at Western Kentucky. Donahue has helped Curzan with keeping her emotions in check and keeping a professional approach to swimming and reminding her that swimming is still swimming, even when the stakes are ratcheted up. To keep her nerves in check during a meet, Curzan likes to go over her races in her head so that she feels less daunted.

And to her credit, Marchionda thinks Curzan has handled the tension of the upcoming Olympic push impeccably.

“The pressure never really rattles her,” Marchionda said. “I think it’s something that she believes she can do, that she can compete with the best in the world. We have worked on the idea that, ‘Oh my God, I’ve got to compete with the best swimmers in the world.’ And it’s like, ‘Well, you are one of the best swimmers in the world.’ Getting that confidence and believing that you belong there just kind of fell into place and took kind of a natural process as her progress continued to move forward.”

MORE THAN A 100 FLYER

In addition to her efforts in the 100 fly that have thrust her into the world spotlight, Curzan should be in the mix in several other events at Olympic Trials. At the April meet, she swam a time of 59.37 in the 100 meter back that thrust her up into a tie for 12thfastest American all-time in the event and sixth among Americans since 2018. Curzan should be in the mix for a spot in the final of the event at Olympic Trials, although it would take another huge jump

[PHOTO PROVIDED BY MARK CURZAN]

to overcome some of the stellar talent in backstroke and qualify for the U.S. team in that event.

Curzan also swam a 54.40 in the 100 free, and with another drop, she could be in the mix to qualify for the 400 free relay at the Olympics. She also swam a 24.44 in the 50 free, but was disqualified for going past 15 meters underwater on the start.

As for the 200 fly and some other longer events, Curzan prefers to avoid those when she can. When she swims her favored sprint races, she likes to remind herself that it’s not the 200 fly to get herself excited. She remembered one meet where she swam the 500 yard free and realized midway through the race how thankful she was to not have to swim that event very often.

“I got to the 300 mark, and I was like, ‘I’m so happy I’m a sprinter. I don’t know how people do it,’” Curzan said. “The 500 short course is not even bad, but it just makes me appreciate distance swimmers that much more. Their training is so hard, and their events are long, and I just don’t know how they do it. It just made me happy that I’m a sprinter.”

These days, swimming is Curzan’s only significant in-person commitment, with her school entirely online for the entire year. When she’s not at practice or doing school work, Curzan has one go-to hobby: “I’m a big reader,” she said. “If I’m bored and I have a good book, that’s always a fun way to pass time.”

In the coming months, she will make some college very happy when she announces her verbal commitment, but Curzan said she is in no rush to make that decision. Curzan has two siblings, younger sister, Kate (11), and older brother, Sean (18), and both she and Sean are looking at colleges at the same time, which she called “kind of weird.” On her relationship with her siblings, Curzan said, “We’re kind of all best friends. We make fun of each other because that’s what siblings do, but, you know, all the love.”

ENJOYING “THE GRIND”

Over the last year, Curzan’s commitment and dedication to swimming have launched her career to new heights, maybe a little earlier than expected, but her passion for swimming is not simply end result-focused. While she admitted that sometimes the thought of the Olympics “will come up and surprise me,” she tries to focus more on the process of the season, and that’s what is most exciting for her. Even as she has piled up impressive accomplishments so close to Olympic Trials, she has been able to shrug off the pressure by staying process-focused.

“I just kind of have a love of the water and just a love of working hard,” Curzan said. “I enjoy the feeling of kind of pushing your body until failure. It kind of sounds weird, but I enjoy the grind, and just being able to see the grind pay off is kind of cool.”

As she has been grinding away at training and racing, the world has had no choice but to take notice. Many elite swimmers only swim close to their best a few times per year, but the youthful Curzan has reached the point where every time she is in the pool, she has the capability of pulling off something astounding. Along the way, Curzan has quickly forced her way firmly into Olympic contention with the biggest swim meet of her life quickly approaching.

CLAIRE CURZAN THROUGH THE YEARS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

[PHOTOS PROVIDED BY MARK CURZAN ]

WHEN IRISH EYES WEREN’T SMILING

Ireland’s Michelle Smith—a four-time Olympic medalist in 1996 who received a four-year ban from the sport in 1988 for tampering with a doping sample—has been defined as being a poster girl for cheating, and by her willingness to cut corners and take advantage of performance-enhancing drug use to make the leap from an athlete of verygood skill to one of elite status.

BY JOHN LOHN | PHOTOS BY TIM MORSE PHOTOGRAPHY

Her presence on the international stage was inconsequential. She didn’t affect the makeup of podiums. She didn’t influence any championship finals. At least, that’s the way the career of Michelle Smith unfolded for most of the years she represented Ireland in global competition.

But at the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games, Smith shined as one of the most successful athletes in Atlanta. To some, her story was about a meteoric rise, a late bloomer rewarded for patience and persistence.

Others, though, knew better.

This sudden surge was about something entirely different—and suspicious.

Between the 1988 (Seoul) and 1992 (Barcelona) Olympics, Smith represented Ireland internationally in seven individual events, never advancing out of the preliminary heats! A best finish of 17th in the 200 meter backstroke in 1988 defined Smith as nothing more than an also-ran, and her performances from 1992—which featured a top finish of 26th in the 400 individual medley—once again rendered Smith, then a 22-year-old, as inconsequential on the international stage.

A NEW OUTLOOK ON TRAINING

Smith was an athlete who may have dedicated herself to her aquatic endeavors and put forth 100% during training sessions. But the sports world is made up of athletes who span the spectrum of talent, and Smith landed somewhere in the very-good sector. She was gifted enough to earn coveted Olympic berths, but not blessed with the skill to naturally appear on an international podium.

If Smith was an insignificant factor through the 1992 Olympics, the same could not be said of the Irishwoman by the time of the 1994 World Championships in Rome. By that point, Smith was training with Dutchman Erik de Bruin, a two-time Olympic discus thrower who had been handed a four-year ban in 1993 by the International Amateur Athletic Association (IAAF) for a failed doping test.

De Bruin, who Smith married in 1996, possessed a unique view of doping, and the advantages provided by the practice. The Dutchman identified disgraced Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson as an idol, despite Johnson being stripped of his gold medal in the 100-meter dash at the 1988 Seoul Olympics for a positive drug test. His words suggested a blind-eye approach to the potential boost of pharmaceutical assistance.

“Who says doping is unethical?” de Bruin once asked. “Who decides what is ethical? Is politics ethical? Is business ethical? Sport is, by definition, dishonest. Some people are naturally gifted, others have to work very hard. Some people are not going to make it without extra help.”

> As Smith was congratulated by U.S. President Bill Clinton for her achievements at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, several athletes spoke freely about what they were witnessing, including Janet Evans: “Are you asking me if she’s on drugs? Any time someone has a dramatic improvement, there’s that question. If you’re asking if the accusations are out there, I would say, ‘Yes.’”

stage, the improvements she made between the 1992 Olympics and 1994 World Championships did not send the Irishwoman into an interrogation room.

They should have.

In the two years between Barcelona and Rome, Smith registered improvements that were highly unusual for a fledgling age-group swimmer, let alone a woman in her mid-20s. In the 400 IM, Smith went from 26th out of 32 competitors in Barcelona to winning the consolation final in Rome. Her time in the event dropped by 11-plus seconds, an eternity in a sport where improvements are typically measured in fractions of a second. In the 200 IM, Smith notched a four-second improvement between 1992 and 1994, that jump enabling Smith to place 12th in prelims at the World Champs.

Perhaps the most startling of her performances at the 1994 World Championships arrived in the 200 butterfly, an event she didn’t even contest at the Olympic Games two years earlier. Racing the 200 fly for the first time in international waters, Smith finished fifth. The effort came on the heels of a bout of glandular fever that disrupted her training in the months ahead of Rome. There was also a change in Smith’s physique, an alteration that could not be overlooked.

“It was a complete metamorphosis,” said Gary O’Toole, a two-time Olympian for Ireland. “The Michelle I remembered had been round and feminine and carried not a lot of excessive weight, but some. I looked at her and said, ‘My God, what have you been taking?’”

Smith’s notable progressions from 1994 were followed by greater success at the 1995 European Championships, which served as her true breakout competition. The meet was also the precursor for what would unfold at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. Racing in Vienna, Austria, Smith left the European Champs with gold medals in the 200 fly and 200 IM, along with a silver medal in the 400 IM. Her times, just as they had in Rome, dipped considerably. Smith was a second quicker in the 200 fly and had improved by another four seconds in the 200 IM. In the 400 medley, Smith lopped five seconds off the time she managed in Rome.

SOMETHING AMISS

With the 100th anniversary of the Modern Olympics approaching in 1996, there was no doubt that Smith would be a medal contender in multiple events. There was also little doubt among rival athletes that something was amiss. Competitors have a keen ability to sense anomalies in their foes, and Smith’s performances were off the charts. Her time drops were complemented by a vast change in her physique, a change that mirrored what was seen in East Germany’s swimmers during their country’s systematic doping program of the 1970s and 1980s.

It didn’t take long in Atlanta for Smith to become one of the most-talked-about stories of the Games. On the opening night of action, Smith blew away the field in the 400 IM, her winning time of 4:39.18 almost three seconds faster than American silver medalist Allison Wagner...and just under 20 seconds quicker than what Smith posted in

the previous Olympiad!

Two days later, Smith won her second gold medal, taking the 400 free in 4:07.25. The event was relatively new for Smith, whose best at the start of the year was a mere 4:26!

Aside from the 19-second improvement within the year, there was additional controversy tied to the 400 freestyle. Not originally entered in the event, officials allowed Smith to participate in the race despite the Olympic Council of Ireland (OCI) missing the entry deadline. It was argued, ultimately before the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), that the Irish Olympic Committee was given incorrect entry information. With Smith entered, American distance legend Janet Evans finished ninth in the preliminary heats and failed to advance to the final. USA Swimming protested Smith’s inclusion, but to no avail. Smith’s late registration for the 400 free was complemented by allegations of doping by Smith.