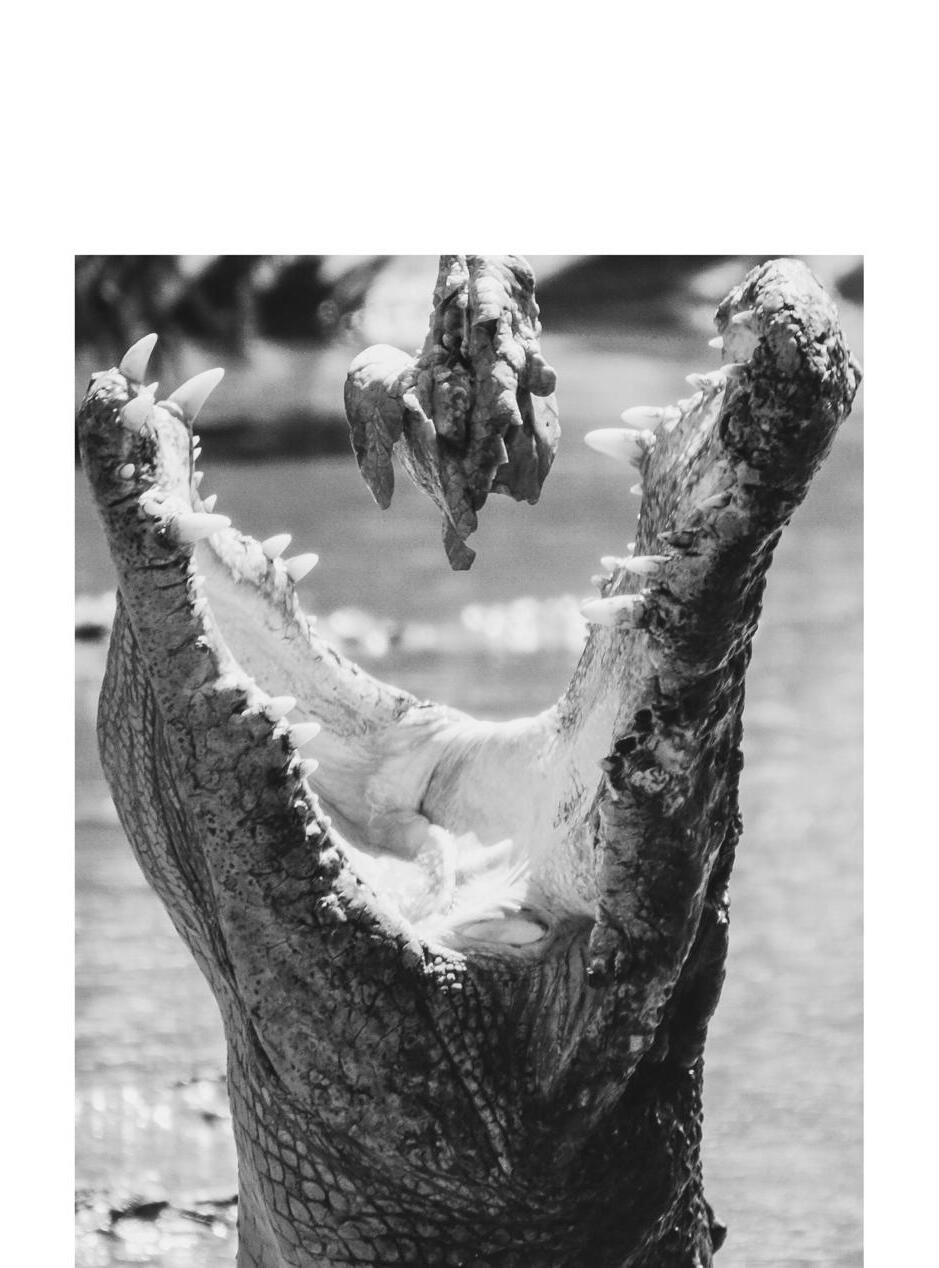

— Mira Grant, Into the Drowning Deep

“As long as there was life in the sea, there would be teeth.”

— Mira Grant, Into the Drowning Deep

“As long as there was life in the sea, there would be teeth.”

The team

Fantine Banulski Editor Print@ssu.org.au

Sophie Robertson Designer Designer@ssu.org.au

With thanks to our extended team

Charlene Behal, Dilini Fredrick, Sanuki Karunatilake, Tamar Peterson, Monique Pollock, Matt Richardson, Nadia Rocha, Alex Schagen, Tilly Schier, Carly Waller.

Stay tuned

Instagram @swinemag

Facebook @swinemag

Website swinemagazine.org

How to Contribute

If you’d like to contribute to future issues or have your work published on our website, check out swinemagazine.org/contribute or reach out to print@ssu.org.au

Advertise in swine

Eric Lee Communications & partnerships officer Media@ssu.org.au

Media Credit

Li Yang, Jordan Rowland, Caroline Hernandez, Duncan Kidd, Roger Johansen, Priscilla Du Preez, AfriMod Studio, Liliya Grek on Unsplash, Karolina

Grabowska, Jacek Dylag, Nida, Holly Mindrup, Marcus Dietachmair, Faris

Mohammed, Bella Pisani, Bogdan condor, Kevin Escate.

The swine team would like to acknowledge the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the land on which the SSU offices are located and our staff live and work. We extend this respect to Elders past, present and future, and to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Swinburne students, faculty and alumni.

As creators, writers, and artists of all types, we feel it is vital to acknowledge the deep connection to land, sea and community held by the Traditional Custodians.

As we may draw inspiration from and explore our connection to so-called Australia, we recognise First Nations peoples as the original storytellers, whose knowledge and wisdom has been, and continues to be, passed through generations since time immemorial. We also recognise the continued attempted destruction of this cultural practice through British colonisation.

Sovereignty was never ceded, always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

If you would like to learn more about what Swinburne is doing to recognise and repair the ongoing harm inflicted by colonisation, you can visit the Moondani Toombadool centre on the Hawthorn campus or online. On their webpage, you can find the transcript of the 2020-2023 Reconciliation Action Plan as well as a video recording of the 2021 Barak-Wonga Oration with the late great Elder, Uncle Jack Charles.

You may have noticed a gorgeous new café opened in 2022 at the Hawthorn campus, but did you know Co-Ground are a social enterprise? 100% of the profits go towards funding local and global projects. They have partnered with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations to bring Swinburne a Co-Ground café in the newly named Yarrwinbu (‘enjoy’ in Woi Wurrung, the language of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation) space on the bottom floor of the AR building, opposite the Moondani Toombadool centre.

Not only is the café serving up delicious coffee and food, fueling many of our swine meetings, but they provide hands-on hospitality training and mentorship.

articles and resources, and consider paying

Indigenous Student Advisers are available to meet at Hawthorn, Wantirna or Croydon campus by appointment during office hours on Monday to Friday. You can also email and schedule a call-back at a time that suits you. To contact the Indigenous Student Adviser, email indigenousstudents@swinburne.edu.au or leave a voicemail on +61 3 9214 8481. Academic skills support. The Indigenous Student Services team provides academic skills support for Indigenous students enrolled in higher education and vocational education.

All Indigenous students enrolled at Swinburne (including Swinburne Online) are encouraged to apply for the Indigenous Academic Success Program. Eligible students receive two hours of tuition per unit of study per week from qualified tutors to assist with their studies. Additional tuition for exam preparation is also provided. The availability of tuition is based on funding and need. The program is provided free to eligible students.

There are also a range of scholarships available as well as an Indigenous Student Lounge at the Hawthorn campus which provides a quiet and culturally safe environment. To find out how to apply for scholarships or gain access to the Indigenous student lounge, visit the ‘Indigenous Student Services’ page on the Swinburne website or email indigenousstudents@swinburne.edu.au or leave a voicemail on +61 3 9214 8481.

All information taken directly from https://www.swinburne.edu.au/life-atswinburne/student-support-services/ indigenous-student-services/ and

https://www.swinburne.edu.au/ news/2022/08/new-on-campus-cafeto-support-indigenous-training-andemployment/

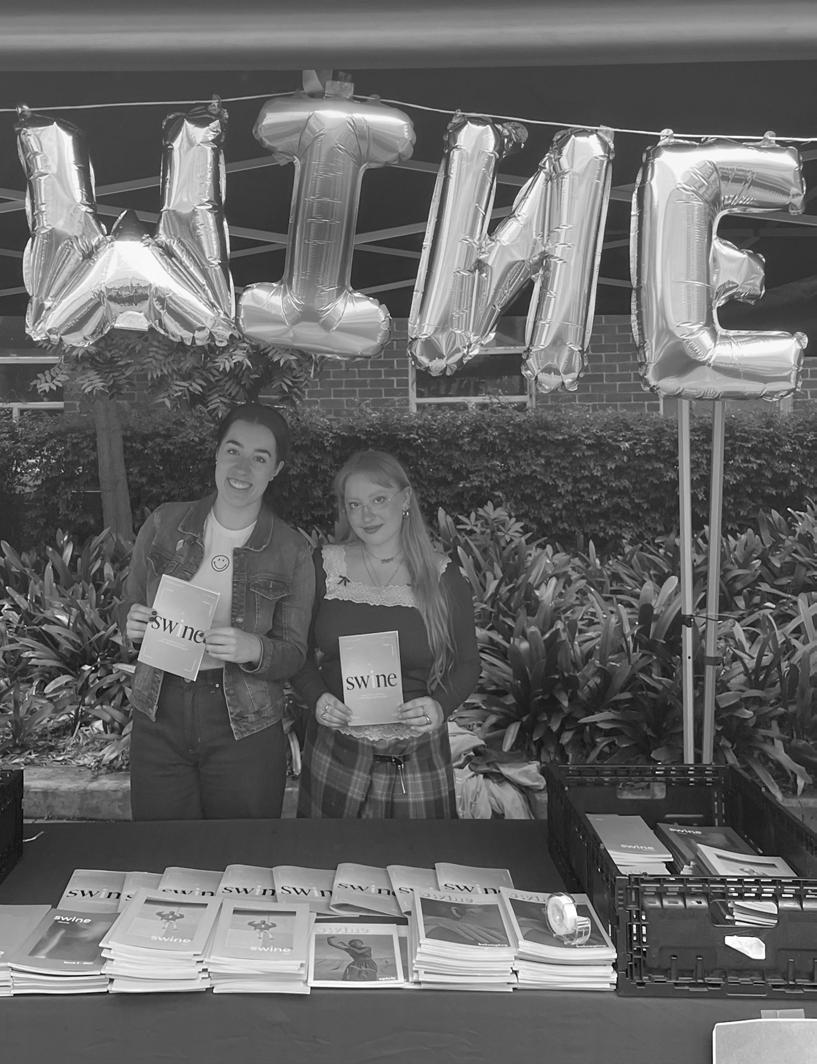

Hello and welcome to the first issue of swine 2023.

Firstly, you may have noticed we are digital—never fear! Print editions are still happening, but are now biannual and will be released at the end of each semester. They will contain all contributions to our quarterly digital issues, alongside the Sudden Writing competition winner.

That out of the way, welcome. My name is Fantine and it’s an honour to be on board as editor of this swine this year.

During my first year at Swinburne, rushing to the library to finish an assignment due at 11:59pm (no doubt started that same day) I couldn’t help but be distracted by a beautiful looking magazine lying in the Latelab. I picked up swine issue 2: spirit, and read it cover to cover. I won’t pretend procrastination didn’t have a part to play, but that doesn’t change just how impressed I was by the design and content—even before I knew it was created entirely by students.

Having worked as a bookseller since I was a teenager, and being an avid reader and reviewer, I was immediately interested. I was studying screen production with a minor in creative writing, and as Associate Professor Julia Prendergast somewhat ominously predicted at a spoken word event, it wasn’t long until I changed my major to creative writing. This is the beauty of swine, it is a place to discover, to experiment and discover oneself in a supportive environment.

This idea of change, of growth, inspired our first theme: Teeth.

Coming into young adulthood, I noticed a number of conversations with friends revolving around teeth. Wisdom teeth needing to be removed, having to book a dentist appointment for the first time, a drunken stumble resulting in a chipped incisor. It became symbolic to me, this huge shift in life encapsulated in a little parcel of pulp and enamel. As we once reckoned with the non-existence of the tooth fairy, we must learn to take care of ourselves and navigate the world. A metaphorical teething.

My short story Puppyteeth explores this notion, and the suppression of fierceness and desire. I find as I grow, as years and experience pile up and sometimes feel overwhelmingly heavy, I wish to return to that child with a bloody smile who feared very little.

I’ll admit I started this year with a niggling fear that nobody would submit. It was quickly quelled and I was blown away by the quality of submissions. Thank you to all contributors, not only for your skill but for the enthusiasm, co-operation, speedy replies, and openness to collaboration. It is difficult to have a piece of yourself out in the world and being edited and published is a vulnerable experience. I know I feel like a slice of my heart is nestled in these pages. So, congratulations<3

Lastly, thank you to the outgoing team of 2022, the time you have taken to answer all our questions (some of them admittedly obvious) is deeply appreciated. Thank you thank you from the bottom of our hearts—we hope to make you proud.

Long live swine magazine, Fantine

I know I have survived the cold, harsh winter because the sun is shining down on my face again.

My freckles have returned after their disappearance.

I welcome them back with open arms.

Little light spots, sun kisses.

My body rides the wave I am gliding on, a gentle pulse, carrying me along.

For the first time in my life I feel as if I am truly in the current.

And yet.

Bottomless black tides push and pull, shoving and demanding.

I am split between the essence of reality and self.

My heart caught in the past like a gasping fish, desperately flopping between two worlds.

Crimson brine oozing out.

My mind, cast out into the future. A long long long line being pulled by wrinkled hands.

Shrinking, unravelling.

My body. My vessel.

Sinking into the deep.

Flecks of light puncture fathoms, lifting me out out out.

Heart and body and mind, woven as one again.

I will ride this wave until I reach the shore, where my bare feet will graze on delicate sands.

Where the universe will sparkle oh so lightly, so I reach up to the lunar lady whilst drifting in the depths.

I lost my first fang in the flesh of an apple.

Like all vipers, the first tooth loss is unmatched.

A bloody stub of white stuck out of the fruit like evidence left at a crime scene. Questions pouring from the newfound channel in my mouth.

My question of “why?” whistled in the wind.

Only to be met with, “It’s all part of life, kid.”

For losing teeth was just another uncomfortable rite of passage I would have to endure.

Significant as one’s first steps; I would learn to wobble my way through the uncertainty.

The first of my pearly whites was tucked under a starry pillowcase.

As the sun rose, there was gold imprinted on the palm of my tiny hand. A motive.

Slammed doors, forceful wiggles and bloody grins followed; a pot of treasure awaiting.

The day the last fang fell was the moment I began to feel a little stronger, older and bolder.

In the dinner party scene of Spike Jonze’s ‘Adaptation’ Meryl Streep, as Susan Orlean, tells her New York bourgeois friends about her latest writing assignment, an orchid thief named John Laroche. Surrounded by books and stylish Manhattan décor, Orlean’s friends top up their wine glasses and laugh as they mock Laroche’s appearance and call him sociopathic for not getting his missing front teeth fixed and …making everybody look at that.’ Laroche is further denigrated by a joke about his potential to give superior blow jobs. This impulse to belittle and treat visibly poor people with contempt sets up a divide important to the film’s narrative—but it’s a divide not limited to fictitious bougie dinner parties.

As a young social work student with hopes of changing the world, I was shocked when my Out of Home Care teacher said, ‘Child protection caseworkers have a saying, “If nothing else, I’m getting that kid braces.”’ I did not then understand what those caseworkers did; that all the counselling, case plans and art therapy in the world was not going to prevent vulnerable kids being treated like John Laroche. But braces could.

If you are host to thirty-two straight white teeth, braces and tooth replacement might seem like a cosmetic luxury rather than a necessity for social equality. But the evidence is abundant and clear: teeth matter. Research participants in the Kelton and California University studies overwhelmingly assessed people with missing teeth as less attractive, less healthy, less trustworthy and less intelligent. Participants said they were less likely to date, employ, live next door to, or value the opinions of someone with missing teeth. And the more teeth missing: the harsher the judgement.

Orthodontists regularly cite an improved dating life or ‘pretty privilege’ as reason to spend thousands of dollars on braces. But straight teeth are not pretty privilege—they are class privilege, and that makes the stakes much higher. A 2015 Yale University study revealed people are significantly less likely to cooperate with people who they know are poor. People are however more likely to cooperate when they don’t know if someone is poor. The impact of ‘visible disadvantage’ is understood by child protection caseworkers and it’s why, in the absence of universal dental care, they fight so hard for orthodontal funding. They can’t fix poverty, but they know the value of at least concealing it.

Melbourne-based linguist (who wishes to remain anonymous and will be referred to as KC) recalls attending yearly appointments at Melbourne’s Royal Dental Hospital when she was a teenager. Each year the staunch atheist would pray for the dentist to tell her that her teeth were bad enough to require government subsidised braces. Instead, she was routinely told to come back again the next year to see if they’d gotten worse. Even as a teenager she could feel middle class slipping further from her reach.

With the cost of braces ranging from $6 000 to $15 000 depending on the type and length of treatment, KC clung to academia. With scholarships, luck and Invisalign—bought and worn in her late twenties—she infiltrated the class that seemed determined to exclude her. But KC’s happy ending is not common. The Australian Bureau of Statistics says one in four people live in a low-income household. For those who are not academically gifted, the cost of appearing trustworthy, dateable, and intelligent is simply too high.

Since its creation and implementation, Australia’s universal healthcare system, Medicare, has evolved to include nursing, psychology, physiotherapy, dietetics, occupational therapy, osteopaths, audiologists, exercise psychologists and speech pathologists. Yet for some reason, the mouth is inexplicably treated differently to every other part of the body. The 2019 Grattan Institute report found no reason that the mouth should be excluded by Medicare and recommended a move towards a commonwealth funded dental care system.

The National Oral Health Plan, subtitled Healthy Mouths Healthy Lives, highlights the undeniable connection between poor oral health and poor overall physical and mental health. People with missing teeth are at increased risk of heart disease, early death, and diabetes. People on low incomes are more likely to have periodontal disease, tooth decay and missing teeth, and those with missing teeth report discrimination and poor mental health. The National Advisory Council of Dental Health reports that ‘A person whose appearance and speech are impaired by dental disease can experience anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, social stigma, and poor social outcomes.’

Every year, The Australian Dental Association writes a pre-budget submission asking the Australian government to fund the National Oral Health Plan, and every year they are ignored. When evidence-based calls from experts to fund dental care are consistently rejected—it is for reasons of ideology. What became obvious with the temporary doubling of JobSeeker payments (when unemployment became a middle-class issue due to the global pandemic) is that governments categorise people into ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ of being poor. We do not apply the same passion, concern, or financial support to long-term poor people as we do to those who we assume are good, hardworking people having a spot of bad luck. We view entrenched poverty as a character flaw and largely the fault of the individual.

Physically, emotionally and socially: teeth matter. That is what my social work teacher tried to explain to me while I was distracted by my privilege and self-righteousness. Of course, my teacher was right. Once employed, I routinely picked up clients from the Royal Dental Hospital after they had waited years for appointments. Teeth, where gaps used to be, were life changing. While I still cling to

I hate my teeth. They constantly remind me what I cannot do, but so desperately wish I could. A currency that has been depreciated of all hope of achieving harmony, waiting to be buried in the dirt.

They are not white nor sharp; they are a sigil of my worthlessness. Raw and dirty from years of neglect and consumption. A weapon, only as strong as its wielder. Forgone in the mouth of a tired fool.

Large protruding fangs once oversaw and led the others. Generals of a forgotten and disordered rebellion; Unfit for this world’s hard conviction. Discriminated against for their brandished defection they were removed from their post; forced to stand in line, disciplined into perfect order.

After the war, through the trenches came the machines, bringing peace and order through metal and pain. The maw—ashamed of what it had become—would force itself shut. For if left unsupervised, the metal wires that pulled and tugged and whipped were overzealous to show off their tortuous madness.

At the end of the regime, these depraved prisoners no longer feared blood, instead they thirsted for it. They yearned for the metallic taste of lacerated gums and whined to be strangled, to be beaten. Their pleas left ignored leaving them stranded and starving for help.

What is left of my lips is a desolate no man's land; the remnants of a battlefield. Only now small sprouts rise from the disrupted soil. The roots unattended, dig deep into my swollen gums. I do not neglect my teeth in an act of vile consciousness, but because I have all the time in the world and yet none of it seems to be mine.

Still, in this abjection.

I will smile in the face of life’s mountain and peer over the edge for all to see my grin of yellow.

For the first rememberable years of my life, I was a dog.

I would walk on all fours and refuse to eat unless food was placed on the floor before me. Dolls and teddies were hastily decapitated, cranial plastic and snowy intestines swept from beneath furniture months post-mortem. The hairbrush elicited fierce growls. I began to smell like fallen leaves, and other, less poetic decay. My howls pierced any door that dared lock me in, bloodied wood splintering beneath my scrabbling nails.

My mother thinks this fact is hilarious. I watch it bring literal tears to her eyes as she recounts it to the smooth-skinned couple who have just moved in two doors down. They nod along, poking politely at their plates of pale tofu.

This ritual unfolds often and without my participation. I find myself at dining tables and doctors' offices, at barbecues and brunches, listening to the history of my formative years.

The climax of her story—my story, I suppose—is a phone call she received from my school. I feel it approaching from the way her voice dips low. My cue to be still. I arrange my mouth into a pleasant tight-lipped curve and clasp my hands where they are visible.

So much blood! She reveals with a flourish, the poor boy’s parents were furious, understandably. She takes a gulp of wine, or beer, or perhaps turpentine, and chases it with, and so many stitches! and, after another swig, I, of course, was mortified. Who knew a seven-year-old's teeth could be so sharp?

She says this last part conspiringly, with an implied wink. It always lands. Gasps mingle with incredulous laughter. The more uncomfortable audience sometimes glances at where I sit, presumably assessing me for signs I may once again become feral.

This man at our table is a laugher. It is a gratingly forced sound.

Thank God she didn’t swallow! he chokes out, lettuce clinging to the soggy corners of his mouth.

This sets off another round of discordant braying, cacophonous against my mother's high-pitched giggling.

I am wondering if he is also an ugly crier when my scalp begins to tingle and the hair on my arms stands on end. I am being watched. I look up to find the woman’s unblinking eyes studying my own, her head tilted.

How can she stand it? The thought is hot and heavy, coiling low in my stomach.

Only when I hear her heartbeat quicken do I realise my smile has widened to reveal a gleaming sliver. Her gaze does not waver. A startling thrill straightens my spine. For a moment, in the flickering candlelight, before darkness expands to swallow golden irises, her pupils appear elongated; vertical

slits like double-pointed teardrops. I make an effort to breathe evenly and turn my attention towards our gracious host.

Unbeknownst to her, Cabernet has sloshed down my mother’s sleeve. For the rest of the dinner, I watch as crimson slowly eats away at white cotton.

I remember the incident, or rather the months of torture preceding it. I had learnt by the second grade, through the embarrassment of my family and a pitying therapist, to hide my canine urges. I was small for my age, and my social skills were not well-developed.

Some children want nothing more than an open field and a big stick. Others have the ability, from very early on, to sense such peculiarity. To sniff out difference.

I never spoke, and yet the boy noticed me. He would scream from across the oval and throw pencils at me in class. His favourite taunt was to wave his pinkie finger in my face, claiming he could crush me with it. He graduated to pushing during games, then pinching, poking, spitting, grabbing, and slapping. He found intense pleasure in figuring out the softest parts of my body. None of me was off limits. It seemed that to him, my suppressed whimpers and bowed head were signs of submission.

Boys play rough, my father would say, it probably means he likes you.

But I was not a boy nor a girl, and I had spent years watching the neighbour’s muscled Staffy clamp down on her toys and shake them so hard her head was a blur.

After the guests depart, muttering excuses and tense assurances of doing this again, my mother finally looks at me. For a second, I seem to catch her by surprise before her eyes narrow in familiar suspicion. The congratulations she slurs out is accusatory—I’ve lost weight—as her index finger digs into my now prominent jawline. I hold my breath until she relents.

When she has disappeared up the stairs, knuckles white with the effort of the climb, I inhale deeply and hold the lingering scent of flesh, mouth-wateringly metallic, for as long as I can bear it. Inhaling again, I search through unfamiliar sweetness—jasmine and saffron, ambergris and bergamot—until I find what I am looking for. Wrapped inside an aeolian antiperspirant is the rich umami of sweat, dirt, and fur. Lightheaded, I clear the table and do the dishes, before slipping out the back door.

I am telling you all of this because lately my jaw has begun to ache. At first, I thought I was grinding my teeth at night, and purchased a mouthguard which remains in pristine condition. My grades are slipping. I can no longer stomach fumbling hands on my skin. Something like hunger is building. I don’t think I can deny it any longer. Each time I look in the mirror, my teeth have grown longer and sharper.

I count Teeth to encounter SleepTongue herding Calcium. A defense against, My Body— Without Sway

My body— Depraved of its Compulsions; Convulsions:

Stimming, Shaking, Chomping. Crouched in Pearly-White Sheets

Limbs with Toothache all over. My body—

Who once knew REM by the cradle…

My body— now Shepherded by blue light.

I count Teeth in an attempt to Sleep

Whatever remains behind my Gums, Or the Scum that coats my Tastebuds. But despite my G-dless Psalm; My Molars are Wanting, Countless and Coveting. Led astray by E133. They walk into the Valley of Darkness Egyptian Bruised and Impinged upon. Wander into the Shadow of Death. They Fear Evil and the Stench of my Rotted Breath. By refusing thy Cane, Thy Rod, Thy Staff, They are Devoured. By a pack of Forty Howling Cavities

Carnivorous holes; who feast on the flesh of my Enamel. Thy Predator is not Decay, But Neglect.

At Night...

I pray to you Heavenly Dentist Flossing in Curly Strand Reverence. I ask you to Admonish the nights I let my toothbrush wither. I beg for Pearly-Wise Redemption Bite my Sleeves in Tattered Exaltation. Chomp my nails in Devotion Repent for My Oral Fixations, Those Lovelorn Notions that assault my brain before Sleep. The Pink, Slobbered Temples–That cause me to suck in my Cheeks, So as not to disturb his pleasure-filled Prayer.

At Morning...

I brush my Fangs. Gritty Reverence, Minty Fervour.

I recite Tehillim on the Highway. To prepare for the Flagellation of their Gleaming and the Bite for my Place that weakens me.

And the Whitening of my Smile. I wish I saved my Lip Balm For Faith Without Fanaticism. I wish I knew then that a Kiss, would not be their Saviour.

I brush my Teeth, An attempt of Discipline before Sleep. When the last Gum forms a Minyan. I Dream of Uncapped Soaring & Plaque(s) of Adoration. I float Unfeathered, untethered. No bands to strap my Brace Or Act as Brake.

In my Dreams...

**Only, in my Dreams. My wings are a Smiles Expanse. The sky is not Above but Around. My psalms don’t stop the crash of the Highway. The Clocks take on Dalí’s physique. I cannot pull the Present and Past apart. There is nothing to measure the passing of moments As I fly. And so I count Teeth. To mark Time.

Incisor past a Canine, the Remaining Molars of Sleep…

They are the unfaltering line of guards.

Stronger than gold, silver, or iron, they stand.

Emerging victorious from flesh in our youth, they claw their way out from above and below, looming tall to begin their duty. Some straight, some not.

The world, time, and experience, test them, and we expose them upon whim or provocation.

Pain, power, pleasure; they stand unchanged. Only our expression gives them meaning.

They never judge while guarding, routinely softening what we throw at them as we force them to collide with their comrades.

As if they can predict we will be rash with our choices, they break it down for us, like an exasperated mother.

They stand, unwavering and stoic, as months, years, decades test their form and composure.

Until—

One by one, the guard crumbles.

Pearlescent turns discoloured; clean lines become ragged edges.

As our bodies begin to falter, so do they.

The last breath snakes a lazy trek, finding crevices and gaps to push through.

Then, all at once, they are relieved of their duty.

The day was dark and grey, as any day in the month of Gipsha, when the humidity came heavy, and the gas lay thick on the banks of the horizon. Burble, only 80 Taipodian years old, was sent out to collect an evening's harvest. Yet they stood stagnant within the tall swinging bushtails, gazing at the purple skies with a netted bag hanging off their shoulder; their thoughts travelled up and away from them, to the pink and yellow stars winking in strange delight.

Burble never understood the stasis of their body and the fluidity of their mind. Though raised to understand the risks and woes of wandering thoughts, Burble could not help seeing more than what was there, more than what they had. Burble reached out their hand, and attempted to grasp at the air, as if they could contain it, as if they could keep it in their net. Baabaa came out from her hut, a woven basket of dried fruit in her arms, called out to Burble and heard no reply. She called and cried out again, but there was only silence. Burble’s mind was burdened, but Baabaa didn’t understand what for, or why for, or where for. Wherever Burble was, Baabaa could never reach them until she grazed her four fingers along their skin, the friction of touch and temperature jolting them back to sometime real, some place tangible. In that moment Burble looked to Baabaa, their pupils flickering from black to blue, and announced in grounded silence,

“I cannot say, my mind escapes me. But my net is dry, and something cruel hides within it.”

“Nothing hides within your net, bitty Burble, you have yet to go out and collect the dol-se nuts.”

Burble looked down, and their mind widened in shock at their empty net. What was it that Burble thought they had caught? Why was it gone? Their hands pawed at the strings, unravelling it until the neat ties came loose and it could hold nothing no longer. They continued to dig, to search, to pull and pull at the meaningless knots, until all that remained was the limp twine that once held it in unity. Burble looked up in dismay and caught Baabaa’s sullen eyes. Burble realised they had done this before, and they would do it again until the end. But only in that moment could they see everything as it was and as it is and as it will be. Baabaa sighed and pulled the meaningless strings from Burble’s hands. An igneous fly buzzed by, performing a dance with a damaged fern, receiving a gift in return.

“Let’s get you inside, for the sun shall die in an hour's time and we must wait for her to return.”

“What for, my bitty Burble?” Baabaa said, running her fingers up and down Burble’s arm. Her actions mimicked the sounds of the wind that would push at the tante trees, allowing their leaves to clap in applause for this song of the breeze.

Inside the hut a small fire burned in the corner, casting subtle pink streaks of light across the floor, and Burble’s and Baabaa’s faces. Burble lay on a mat of curled cradle leaves, their legs tucked close to their body, tail between their legs, and their hands outstretched before them, their fingers still reaching for something. Baabaa sat down cross-legged at the edge of the hearth, weaving a new netted bag for tomorrow.

On that particular night the clouds gave them rain, hailing heavily on the brittle roof. The noise smothered Baabaa’s worried cries, she was not sure if her child would ever come out of their own mind. Burble woke and finally saw Baabaa’s

“Baabaa, I am afraid.”

tears fall onto their new netted bag, a line dug its way deep within their brow and their eyes stayed confused.

“Baabaa, the bag will rot.” At Burble’s small words, Baabaa looked up.

“It will not Burble; you are seeing something not here.”

“But what if it rots as I’m picking the dol-se nuts, and I have nothing but my hands to contain them. You will grow angry at me, for I can only carry so much.”

“But it will not! For you have never picked a dol-se nut, and you will not!” Baabaa said, her voice was hoarse with a carnivorous sadness. She was in pain and was growing sicker and sicker each day from Burble’s mind.

“Why?”

The innocence in Burble’s voice stung Baabaa and she remained in that stasis for minutes or hours. She could not answer this simple question that she had asked herself many times. So instead, she smiled, and in that smile Burble saw the pink and yellow stars from the morning sky.

The next morning Burble stood again within the tall, swinging bushtails, and stared at the stars. A netted bag sat on their shoulder once more, as they stretched their arms out, hands grasping to collect the stars. Baabaa silently watched them from the hut and hobbled over, grazing their arm with her four fingers once more.

“Baabaa, I am afraid.” Burble uttered, and was met with silence, and the continued stroking of her fingers on their shoulder.

“My net is dry, and something cruel hides within it.”

Baabaa gave no reply.

Burble looked to Baabaa, who remained face down, and silent. They gazed at their bag, and began to unravel their mother’s weaving.

At each knot a tooth fell out, polished until they shone with the colours of pink and gold. Burble screamed, their face twisted in confusion, stuck between delight and disgust. At the unravelling of the bag there were twenty teeth within Burble's hand. They looked to Baabaa, who faced them now, smiling a big empty smile. They looked to the purple sky to see that the pink and yellow stars were gone.

I lost two teeth and you in the same week

A part of me turned against me, cavities filled with poison, the pain unbearable

Like you

Waking from surgery, numb, disoriented

My tongue roams my mouth, your former domain, exploring its new topography, And is surprised by the absence

Like rolling over in bed and finding you gone

Feather-hemmed dresses are fun to wear, and my wings are nothing short of dazzling, decorated with jewels and gems as bright as they come. Wearing them never gets old.

The bells on my slippers tinkle as I catch an updraft, swooping over the rows of white houses in this particular cul-de-sac. They sit in perfectly picketed rows, pale wood contrasting against the year-round green gardens. I have to be precise, careful, when collecting in these sorts of areas. One could easily visit the wrong house, which although rare, is never good. I make sure to rely on the house numbers rather than the houses themselves.

Of course, the majority of families here reside in houses that fit those who call it home; a garden to play in and a car to each parent. These homes are sometimes white, though brick seems to be more common. I admire the way the shiny tin roofs reflect the warm yellow streetlamps lighting my path through the neighbourhoods. Tonight’s collection is a comforting weight as I make a sharp turn upwards.

Breaking through the first layer of clouds, I pass hovering groups of newly returned Collectors, chatting whilst they wait for assignments. I continue flying up, searching for a swirling grey cloud. When I spot a particularly dark nimbus, I place my pouch in the eye of a small hurricane. Once it has been safely whirled away, I look around for a place to rest. Just as I spot a comfortable looking cumulus, the chime for a new tooth echoes through the sky. It is an ominous sound that happens everywhere all at once, crackling through the clouds.

The soft slumber I was drifting into is abandoned as doves circle above me. A scroll falls as delicately as a feather into my lap. As I unfurl the paper and begin reading, my heart skips a beat and my wings flutter with excitement; I can’t help but smile.

270 CRESCENT DRIVE. 6-YEAR-OLD BOY. UPPER CANINE.

Crescent Drive. I know it well. I pocket the scroll before anyone else can see the address.

I’ve been going to this street for years. The mother at number 270 has five kids. Three girls and two boys. They have always lived in the same little house, too small to fit all six of them but they do their best. These are the families I love visiting the most, the ones who, more often than not, live in homes that aren’t theirs with gardens that are only green when the weather allows it. Their cupboards may be empty, but their homes are always brimming with joy and laughter, filled in a way that no amount of material items could achieve. Whenever I feel their love for one another, my heart grows a bit bigger.

If I’m not mistaken, this little boy is the baby of the family. He will be the last child at 270 to lose his teeth. I have seen each of their excitement through the years, but also their

hardships. As the third child, a gorgeous little girl, lost the last of her baby teeth, her demeanour changed. She began to realise that a single gold round wouldn’t do very much to help her mother. That’s the part of this job that I hate the most. Whilst I love going there, it’s always hard.

With renewed determination, I head towards the moon until I reach reception, where a bright red robin drops a stack of paper before me. Skimming over the familiar paperwork, I scribble in the estimated departure and arrival times, list the items to take with me, and tick all the boxes saying that I know the path and will make the collection with proper authority. Then my eye catches on a peculiar detail and tears form, threatening to fall. I am not to take gold to this deserving family, but silver—practically nothing.

Slowly, in disbelief, I gather the things I need for collection: a little velvet bag that carries the rounds until we reach our destination, some glittering dust in case the kids wake up—a small sprinkle will ensure they believe it was all a dream—and, most importantly, an extra pair of shoes. Our slippers aren’t as decorated as our wings but they too are adorned with gems precious to humans. The colour depends on our rank, with seven possible hues. I have blazing blue sapphires, held in place with golden wires. There are only two ranks above my own—a deep purple, then a powerful violet that represents only the most senior Collectors. Despite their value, you would be surprised at how often our shoes fall off when we are in a hurry.

My journey to 270 Crescent Drive feels different this time, solemn. I descend to a level where I can see the winding streets. Usually, I appreciate the areas I am flying over, but not tonight. The pearly white houses don’t fascinate me, the gardens don’t catch my eye. My path is uninterrupted and quick. Direct to 270 Crescent Drive.

When I reach the house, I float above it for a little while to gather my thoughts. My quivering wings mimic my heartbeat. I’m not supposed to, but I make a detour past 270 every so often and watch the family. I have seen how the food on their table often goes further than just their own. Kids living on the streets know they can knock on the paintflaked door and leave in better shape than when they went in; with food in their bellies and buttons sewn back onto their clothing.

I lower myself down onto the dusty ground outside of the kids’ shared bedroom. Four in one bed now. I hear the voices of their mum and what must be the eldest child coming from the kitchen. I glide over to the permanently greasy window, and through it watch the hazy pair at the dining table, heads in their hands, as they try and figure out how they’ll afford the already overdue bills. My heart sinks to the very pit of my stomach.

I take a deep breath in. And out.

In the childrens’ room, I softly close the window behind me. The youngest, the little boy I am here for, hugs his teddy bear tightly. He does not stir when I retrieve the lump from beneath his pillow. As always with these children, the tooth is neatly wrapped, proudly awaiting my collection. Curiosity gets the better of me and I unfold the tissue. I find exactly what I thought I would. It has no shape and is a dark yellow colour with a sharp odour to match. A rotten tooth. I wonder if it has fallen out because it was time, or because the roots have wasted away and it had no choice but to fall. I haven’t often collected a tooth such as this one, but each time that I have, it has come from this area of town.

Pulling out the little purple velvet bag I brought with me, I take out the silver round, and replace the precious parcel. I stand straight and quietly shake the bag while I think.

Eventually, the soft colours of sunrise spur me into action. Working quickly, I hide shining gold everywhere I can; under clothes, in drawers and boxes. Buried under blankets and in the tin that houses safety pins and band aids. In nooks used every day and crannies that won’t be found right away.

Before I leave, perhaps for the final time, I scan the childrens’ room. The two blankets barely cover them all. The second eldest girl, the brightest but shyest of the children, has her feet hanging off the side of the bed. I stare for a second before I look down at my own feet, covered in my bejeweled shoes. Shoes that look like they could fit her.

As I am leaving, I feel an urge to look up one last time. I am being watched. I turn, half of my body out the window, to find the sweet face of the youngest little boy turned towards me, hair mussed and eyes wide. I draw a finger to my pursed lips and, after a moment of contemplation, he nods ever so slightly.

As I fly, hurrying to beat the rising sun, the dawn air tickles the soles of my feet. It’s a good thing I packed that second pair of slippers. Like I said, our shoes fall off when we fly, don’t they?

What big eyes you have… (Innocent and sweet),

What big ears you have… (Don’t talk; just listen),

What big teeth you have… (Pearly whites with no bite).

Excluded, Misrepresented, One dimensional, Mother, Maiden, Crone.

What big eyes you have… (But we can’t see ourselves),

What big ears you have… (To hear just how wrong we are again),

What big teeth you have… (Shown as a prop, but no meat to the role).

Manic Pixie dream girl, The other woman, The wicked stepmother, The sweet old grandmother, The strong female protagonist, She’s not like other girls.

What big eyes you have… (Painted and narrowed),

What big ears you have… (Decorated and pricked),

What big teeth you have… (With ambition bared).

Archetypes, Tropes, Stereotypes, But we’re not fiction.

Lyssa Stevens

Lyssa Stevens

Sit still with your lips sealed and your eyes covered. Your shoulders are tense. Your tongue is tied. You look so weak. Keep your palms open and wait for the world to decide your fate. Why does your chest refuse to let go of the breath sitting at the bottom of your lungs? Let it go. Let it curdle into a scream, a cry, a dry heave.

You weren’t meant to live like this. Wagging your tail for a hand that presents uncertainty while your mouth is covered with a muzzle and your neck is strangled by a leash. You were meant to scream into the sky and bare your sharp teeth. Let that breath go. Let it be what it was born to be. Show the world that you’re not as weak as it paints you to be. Show me that menacing smile. I know it’s scary to try. But would you rather continue sitting still, hoping for a chance to be the one extending the hand?

So, bite the hand. Make it dance. Paint it red. Listen as it sings that wretched song of pain. Hurry. Strike first. Before it beats you to it. You cannot live like this forever. Now, bare your teeth. Show me how scary you can be.

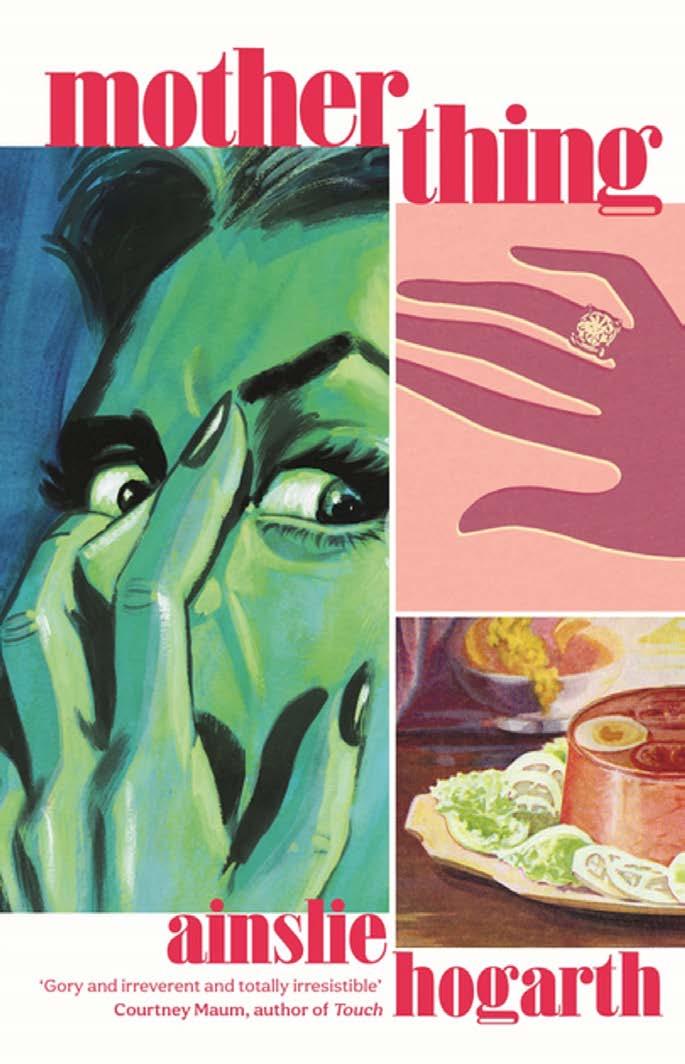

This April we've decided to go dark and strange with ‘Motherthing’ by Ainslie

Hogarth, a darkly funny take on mothers and daughters, about a woman who must take drastic measures to save her husband and herself from the vengeful ghost of her mother-in-law.

We will be meeting at Hammer & Swine

(UN building, where the bookshop is) at 6 pm, though we understand classes end at different times so don’t fret if you’re running late.

Shoot us a dm @swinebookclub if you have any questions. See you there!

When: 6 pm Thursday April 27, 2023

Where: Hammer and Swine

(UN Building, 3rd floor)

Book: Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth

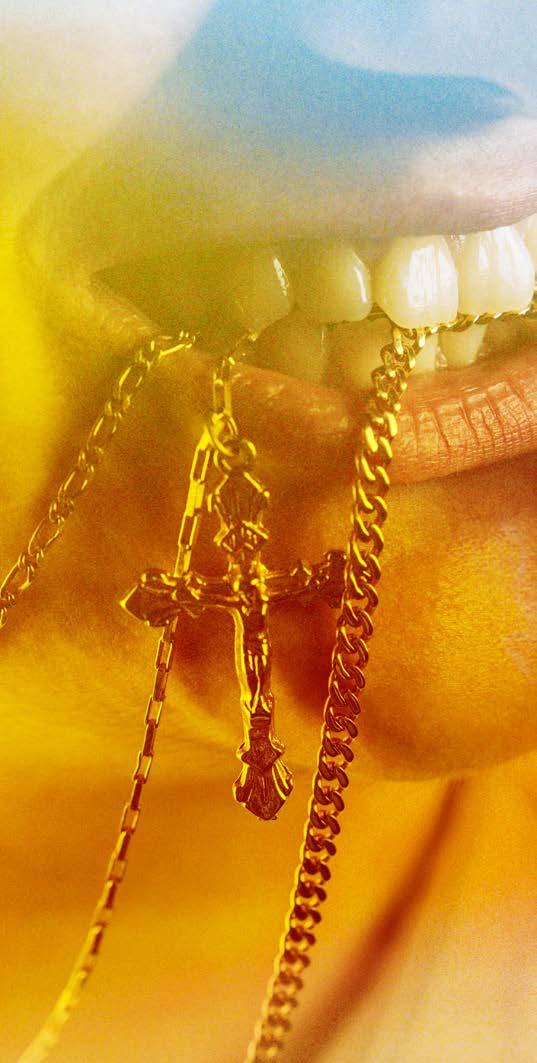

“Biting’s excellent. It’s like kissing — only there

In collaboration with Swinburne Writing Programs

Submit your unpublished fiction, creative nonfiction, and hybrid forms of writing under 400 words for the chance to be published and win $150!

Any questions? Please contact Associate Professor Julia Prendergast: jprendergast@swin.edu.au

T&Cs at swinemagazine.org/swc

Deadline: Sunday April 9th

Send anonymous submissions to comms@ssu.org.au

Hesitant? Meet Swinburne’s welcoming writing community and listen to student readings at the Tell Me spoken word event on Wednesday April 5th at the Glenferrie, 6 pm start.