10 minute read

Brutality in Blue

Homophobia can wear a badge and carry a gun, according to a new Amnesty International report on police brutality against lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgenders. The research shows how stonewalling perpetuates the problem. By Walter Armstrong BRUTALITY Blue IN The crowd attempts to stop police in the infamous 1969 Stonewall Inn nightclub raid in New York City. The routine police raid sparked a spontaneous rebellion and helped ignite the gay rights movement.

In 1997, after a suicide attempt, Edward Thompson finally had “the talk” with his wife. He told her that the man she married felt that inside she was a woman. And he would rather die than go on living in a male body.

His wife took it hard. She kicked him out of the house he’d built and launched a take-no-prisoners divorce suit. He also faced hostility in the community as he explained his breakup and began his physical transformation to a woman. Friends who were judges, lawyers and police officers—pillars of the Lehigh Valley, Pa., community where they lived—turned on him. A court ruled that he was “a potential danger” to his 10- year-old daughter and barred almost all contact. He lost his job managing a major construction site. “I went from living in a half-million-dollar house to living out of my truck,” says the 49-year-old transgender activist and painter, whose first name now is Rachel.

On Christmas Eve 1998 Thompson—who had by then been living full-time as a woman—was driving to see her daughter for the first time in a year. Her 18-year-old son from a previous marriage came along. The three were planning to spend the holiday together. Then a police officer pulled her over. “I was on hormones and wearing—by court order—a suit and tie, so I looked like an effeminate gay guy,” Thompson says. “The cop started right in with vicious comments. ‘Hey faggot, is that your boyfriend?’ he asked. I told him it was my son. ‘Looks like a f—-in’ queer to me,’ he said.”

Seeing that Thompson’s auto registration had just expired, the officer ordered her out and the truck impounded. “But the officer’s abuse threw me into shock. I couldn’t move,” Thompson says. “The cop grabbed me and dragged me out. I was having a breakdown. He laughed, hurled insults and kicked me as I lay on the street sobbing. My son, the brave kid, argued with him that I needed to go to the hospital.” Instead, the police officer simply stared as a dazed Thompson rushed into incoming traffic. Twenty minutes later she made her second suicide attempt, jumping off a bridge into frigid water. “I was heartsick. I knew I’d never see my daughter again,” she says. “But the cop was what sent me over the edge. Just because I looked different in a way that pressed his buttons, he was having fun treating me like a piece of human garbage.”

Every day in gay America brings disturbing variations on Thompson’s experience. Amnesty International’s groundbreaking report, Stonewalled: Police Abuse and Misconduct Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender [LGBT] People in the U.S., provides the evidence, based on exhaustive research, including more than 170 interviews with survivors and advocates, surveys of dozens of police departments and investigations of police policies and training in four major cities. The report found that verbal abuse and harassment are routine. So are a range of discriminatory practices, from selective enforcement of the law, such as profiling gay men as public-sex offenders and transgender women as prostitutes, to selective non-enforcement during investigations of hate crimes and domestic violence.

When officers police by prejudice, permitting gender stereotypes to dictate decisions, punishment often falls on victims rather than criminals. In one Amnesty International (AI) account of a domestic dispute between lesbians, the officers arrested the woman who looked more masculine, even though she had placed the 911 call; in another, officers advised the woman who looked more feminine, “You need a real man.” Although statistics are scarce, most experts agree that, as with anti-gay bias crimes in general, reported cases of police LGBT mistreatment are only the tip of the iceberg.

Confrontations sparked by an officer’s homophobic slur can escalate into outright physical or sexual violence. After being attacked on the street, a young gay man told AI, he flagged down two officers on patrol; they responded with taunts, then handcuffed him, pushed him into their car and sprayed Mace in his face when he demanded to know why he was being arrested. And the violence comes in different forms. A Native-American transgender woman told AI, “The police

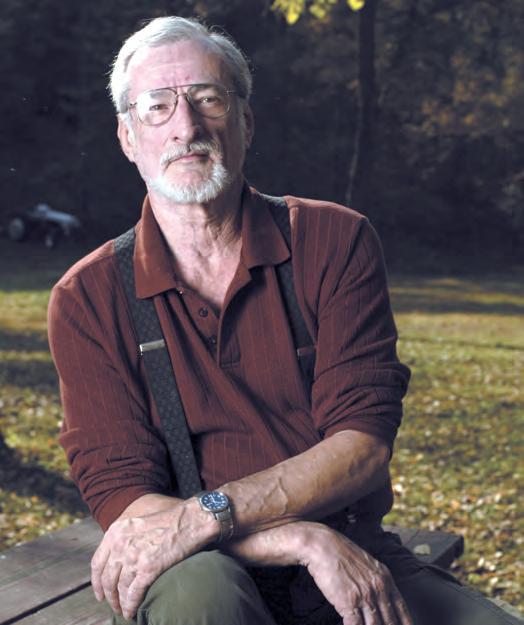

Robert Boevingloh.

Rachel Thompson, who was physically assaulted by police officers in 1998 and again in 2000. Her gender reassignment surgery has reduced her risk as a mark for violence.

are not here to serve; they are here to get served.… Every night I’m taken into an alley and given the choice between having sex or going to jail.”

That transgender individuals, particularly women and young people, bear the disproportionate brunt of police brutality against LGBT people is among the AI report’s key conclusions. The AI report also found that within the LGBT community, people of color, youth, the homeless and immigrants are at greater risk of police abuse. AIUSA Executive Director Dr. William F. Schulz commented at the Sept. 22 Stonewalled press conference in New York City, “Transgender individuals, people of color and the young suffer disproportionately, especially when poverty leaves them vulnerable to homelessness and exploitation and less likely to draw public outcry or official scrutiny. It is a sorry state of affairs when the police misuse their power to inflict suffering rather than prevent it.”

The problem of police brutality isn’t new. Ever since the 1991 Rodney King beating, racial profiling has triggered national headlines, debate and investigations. Yet police abuse of people in the LGBT community remains largely under the radar.

The fact that many people still hold homophobic attitudes and behaviors offers one explanation. It wasn’t until 1999, for example, that Gallup’s annual poll found that 50 percent of Americans “consider[ed] homosexuality an acceptable lifestyle.” Equally telling, Gallup polled Americans one month after the Supreme Court’s 2003 Lawrence v. Texas decision decriminalizing sodomy and discovered that, for the first time in a decade, acceptance of homosexuality had fallen significantly. A police badge, of course, confers no inoculation against homophobia. In 2004, in the first study of police homophobia, psychologists at Sam Houston State University sampled 152 Texas officers and found that a majority held anti-gay attitudes.

It’s not uncommon, as the Stonewalled report shows, for LGBT survivors to report a hate crime only to have the police trivialize, misidentify or ignore their complaint altogether. When the alleged perpetrator is a policeman, this stonewalling may, given the prevailing “code of silence” in police culture, morph into cover-ups, including retaliation against not only the victim but against any outspoken officer who crosses the “thin blue line.” In this fall’s media coverage of the AI report, for example, Chicago’s Sgt. Jose Rios was typical of police officers who downplayed the findings. “I know there are gay officers in every district, and I have heard not one complaint about mistreating of the LGBT community,” Rios, himself a liaison to that community, told The Chicago Sun Times. Stonewalling, in turn, reinforces LGBT suspicions of the police and discourages victims from seeking justice—a problem compounded by some people’s sensitivities about being outed as gay. This phenomenon is illustrated by the fact that despite Rios’ disavowal, the Stonewalled researchers recorded several testimonials from Chicago-area victims of harassment. In endless-cycle fashion, this collusion of silence enables law enforcement to dismiss the entire issue with its “few bad apples” refrain. To break the cycle, survivors must break their silence. “The biggest problem…of wrongfully charged defendants,” according to Andrew Thomas, a San Antonio attorney, “is that 95 percent are so embarrassed by the charge…they are afraid to fight.”

Robert Boevingloh, a gay 61-year-old disabled Viet Nam veteran with HIV, wasn’t afraid. Arrested in spring 2000, in St. Louis, in what some police dub “bag a fag” (entrapment exercises in “gay cruising” spots), Boevingloh says, “I refused to plead guilty to ‘lewd and lascivious’ because I have this thing about fairness. I felt so violated—even my own sister didn’t believe I was innocent.”

Boevingloh went to trial without a lawyer “because I thought it was an open-and-shut case—talk about naïve!” In court, he says, his arresting officer—the undercover officer to whom Boevingloh had merely said, “What a glorious day!”— testified that Boevingloh made sexual advances, grabbed his crotch and then went into the bushes and lay down. Boevingloh was found guilty and sentenced to two years probation. “During my sentencing, the judge announced to the courtroom, ‘Since you have AIDS, you’d better be careful because if you have sex with anyone, you can go to jail for 10 years.’ Everybody gasped at me. I never felt so vulnerable,” the former vet says.

Boevingloh endured his probation in a state of dread, finally moving to a different city. “Before all this, I had only good feelings about cops. My own brother was a police officer killed in the line of duty,” he says. “But now? If this is the justice system in America, it’s broken.”

Yet advocates believe that what’s broken can be fixed. Just as there are many police officers who take no part in antigay abuse, there are some who break ranks to publicly acknowledge the practice—the crucial first step toward addressing the problem. Sgt. Brett Parson, of the Washington, D.C., Gay and Lesbian Liaison Unit, told The Washington Blade, “Countless people…have told me about experiences just like the ones Amnesty uncovered in their report. It runs the

Transgender activist Mariah Lopez speaks at the AIUSA press conference for the Stonewalled report, with AIUSA Executive Director Bill Schulz and Sargeant Brett Parson.

gamut—from the very worst physical abuse to…intentionally demeaning language.” Parson was first in line to sign Amnesty’s “Pledge for Professionalism,” which asks police officials to affirm “their commitment to combat discrimination and violence against LGBT people.” The San Antonio ExpressNews reported that while the city’s Chief of Police Albert Ortiz criticized AI’s report for over-emphasizing unsubstantiated accounts by survivors, he backed its recommendations and signed the pledge.

The week in September that saw the release of the Stonewalled report was marked by three significant developments. An openly gay police officer was named a finalist for the Los Angeles Police Department’s top job. The Atlanta police department fired an officer for anti-gay verbal abuse, and the department implemented new policies on treating LGBT people with respect. And the U.S. House of Representatives passed the first bill to expand federal hatecrimes laws to protect “gay or transgender” people.

While hardly a perfect storm, these advances may remind everyone who cares about social justice to keep their eyes on the prize. “For many, it is easier to give in than to struggle. Sometimes you feel so damaged, you don’t realize you are worth the fight,” says Maria Lopez, a young Latina transgender activist falsely arrested for solicitation. “But we are all worth the fight. Change can happen. The launch of this report will help—if we join forces to insist [that] police protect all human beings.” ai

Take Action

AIUSA’s OUTfront Program works to protect the human rights of LGBT people around the world. Following the release of Stonewalled, activists are pressing police departments to sign AIUSA’s Pledge for Professionalism. They are also seeking an investigation into the case of Kelly McAllister, a transgender woman who allegedly was mistreated by Sacramento County Sheriff’s Department deputies and allegedly raped by an inmate while held in jail. To protect the rights of LGBT individuals, see amnestyusa.org/outfront or call OUTfront staff at 212-807-8400.

Learn more: Online chat with Sgt. Brett Parson of the Washington, D.C., Police Department, OUTfront national field organizer Ariel Herrera and other experts on Dec. 15 from 1-2 p.m. Eastern: amnestyusa.org/outfront.