13 minute read

LANGUAGE ARTS AT SYCAMORE

RISKS & LOVE

“It is not enough to simply teach children to read; we have to give them something worth reading. Something that will stretch their imaginations— something that will help them make sense of their own lives and encourage them to reach out toward people whose lives are quite different from their own.” -- KATHERINE PATTERSON / NEWBERY

Advertisement

MEDAL-WINNING AUTHOR

At Sycamore, the way the Language Arts curriculum flows from the youngest students all the way through the graduating class of eighth graders is not an accident. Language Arts teachers across all three divisions (Early Childhood, Lower School, Middle School) work together to provide continuity to engage students in a unique combination of reading, writing, speaking, and listening. A Sycamore graduate becomes a well-rounded learner because what they receive from their Language Arts teachers stays with them. Teachers focus on helping them acquire skills that will benefit them daily with decisions, with relationships, and with discovery.

Developing good readers allows for students to gather a perspective on the world. In combination with writing, critical thinking, and an ability to share ideas through speaking, being a self-motivated reader is one of the most important ways a student can learn. Teachers at Sycamore work hard to develop that independence.

As we talked to teachers, we asked all of them similar questions: How do you create independent thinking, self-motivated readers? How does Sycamore foster an environment that is supportive of creativity and individual ideas, with reading, writing, and also with public speaking?

Sycamore teachers Marissa Argus (Kindergarten), Deb Stewart Second Grade), Chris Herron (Third Grade), and Beth Simpson (Middle School) helped us understand the Sycamore process of teaching Language Arts and ushering students into Early Childhood, through Lower School, to Middle School, and beyond.

TAKING RISKS

Regardless of subject matter, teachers at Sycamore foster environments where students know that not only their work but also their ideas are valued and appreciated. To balance those two pieces requires a pact between teacher and student: The road to knowledge is marked by missteps, and detours, but ultimately, trust will get us to the truth.

“In all of my years of teaching, I have always stressed to students that I won’t assign anything that isn’t worth doing,” Deb Stewart, says. “In my class I ask students to take risks, put forth their best efforts, and know that making a mistake is a sign of growth.”

“We encourage lots of risk taking by reading all the Kindergarten students the book Bubble Gum Brain, by Julia Clay,” Marissa Argus says. “It was actually recommended to me a few years back by a Sycamore family with two sons in first and second grade. The book is all about fostering a growth mindset and has really great kid-friendly language that we use throughout the year with the kids. Using our ‘Bubble Gum Brain’ is a mantra we come back to week after week, and it really helps the kids remember that trying is what’s important and everyone makes mistakes - that’s how we learn. I try to model as many mistakes as I can in front of the kids so they see I am human.”

“It is beneficial to model for my students how I, the teacher, take educational risks and meet challenges,” says Chris Herron. “The first day of every school year I give my kids a script. Whenever I make a mistake, I say, ‘Oh, Mr. Herron!’ and they know that they should echo that phrase. It never fails to make them laugh, and it destigmatizes making mistakes. Students feel safe and empowered to take risks when they see adults doing the same.”

THE PROCESS

With a template that allows for mistakes to happen as they find the right answers, students at Sycamore are encouraged by teachers to take chances, something Language Arts teachers say is critical to higher-level thinking. An important piece in the curriculum is writing and sharing of their work, allowing the students from an early age to feel comfortable getting feedback and knowing how to take it as constructive and not personal.

“Even at the young age of five and six, we are practicing facing our audience, speaking loudly, showing the pictures, and being proud of our work,” Argus says of her Kindergarten students. “We are learning to give thoughtful and specific compliments after someone shares and soon we will be learning how to give feedback. Feedback in Kindergarten sometimes looks like asking questions such as, ‘Why did you have the character do that?’ It sometimes looks like a suggestion for an edit, or helping to spell a tricky word. The kids are learning to also accept praise and feedback and take it both graciously and as a way to grow as a writer.”

Stewart helps her Second Graders to understand what the process means. “One way to help students take educational risks is to stress the difference between the process and the outcome. In second grade, we often talk about how a task can be difficult but fun. I also acknowledge that it is much more important to me that a student is willing to participate in class and share his or her thought processes than whether the answer is correct. This is how we learn from one another.”

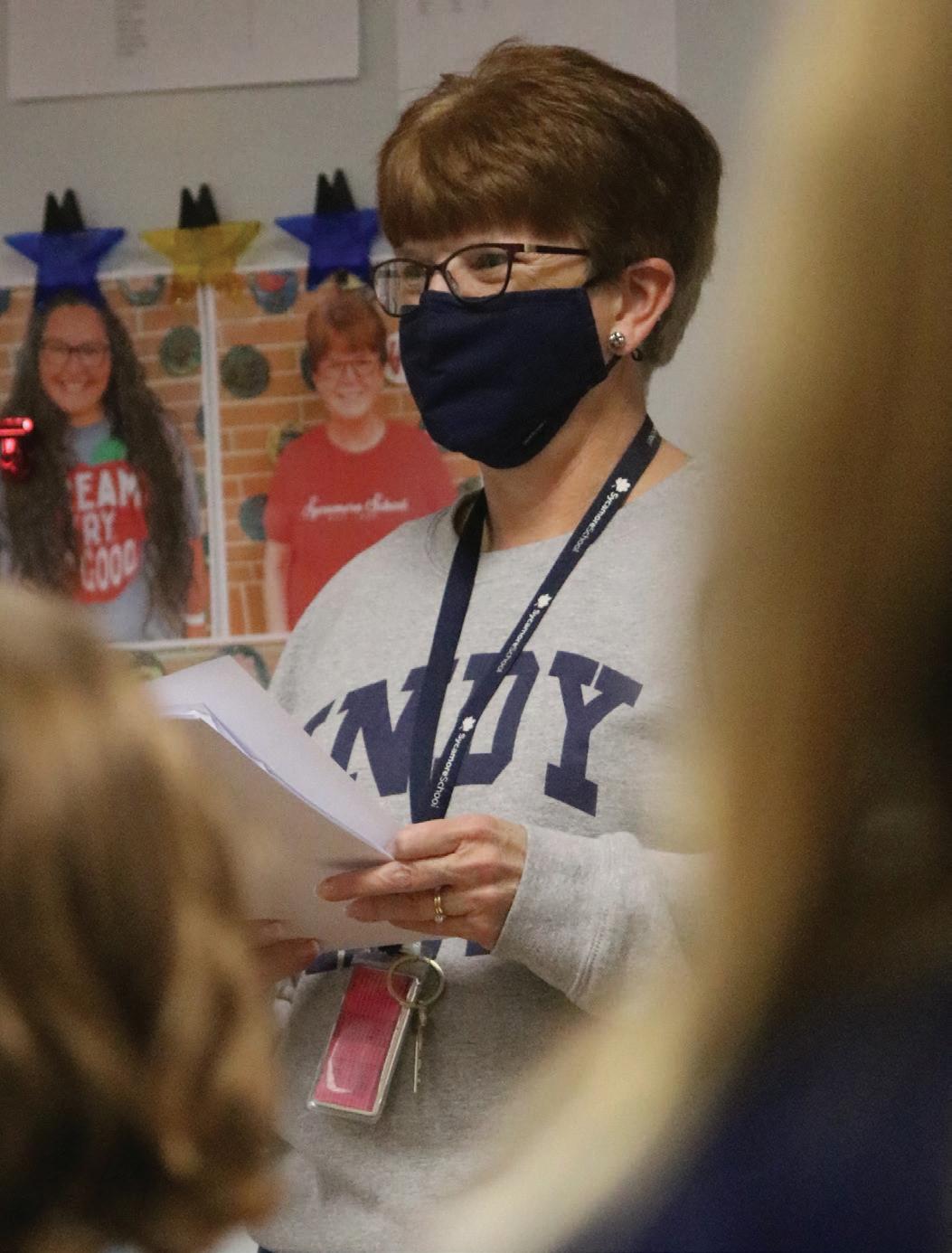

That process of rewriting, revision, and reworking that starts in the youngest grades permeates throughout Sycamore. In Middle School, Beth Simpson carries those ideas to her students all the way until graduation, getting them ready to head to high school. “I am a big believer in the importance of the process over the product,” she says. “Revision and fixing mistakes is one of the best ways for kids to learn, and is hands down one of the most

ABOVE: BETH SIMPSON TEACHING DURING THE 2020-21 SCHOOL YEAR

powerful ways to teach writing. I let kids know that I read every word that they write, and students are almost always allowed, and encouraged, to revise, using the notes I give them. For all of us, the process of writing is rarely finished; work can always be improved with an additional proofread and revision, and I think it’s so important to teach and normalize those skills to our Middle School students.”

WHAT IS THE HARKNESS METHOD?

Simpson had been a longtime Middle School teacher before joining Sycamore in 2013, teaching in public schools. After arriving at Sycamore, she was encouraged to follow her passion for building a more student-led classroom, which includes teaching with the Harkness Method. Developed by Edward Harkness in 1930, he believed learning should be a democratic affair, with a simple concept: You explore ideas as a group, developing the courage to speak, the compassion to listen, and the empathy to understand. It’s not about being right or wrong. It’s a collaborative approach to problem solving and learning. The primary goal of the method is to place students in the driver’s seat of their learning and to make learning a more participatory process. To achieve this, students come to the table having read a piece of material, and they actively participate in a discussion about the content while the facilitator monitors

the discussion, and redirects and interjects when necessary. With the Harkness method, the teacher gives up the need to guide students to the solution. A sign of a high-quality Harkness discussion would be one that requires little to no direction by the teacher; instead the learning occurs student-to-student.

In the beginning, Simpson thought there was no way this method could work with Middle School students. “Honestly,” she says. “When I was initially trained and began using this method, I was incredulous: How could I possibly be sure students would cover all of the important things that I wanted them to discuss? But I realized that not only do they cover what I would have asked, they dig deeper, often making cross-curricular and complex connections I had not considered. Because they are reading to discover their own questions, instead of merely hunting for required answers, the analysis belongs to them and has yet to be lacking in depth or sophistication,” she says. “During our Harknesses, I’m largely quiet, only interjecting if discussion is wildly off track or students have settled on incorrect information. One of the coolest things is that I have seen this transfer to traditional classroom discussions and even students’

written work, and I truly believe it is because they recognize the ownership they have in their learning.”

CREATING INDEPENDENT READERS

“The things I want to know are in books. My best friend is the man who’ll get me a book I [haven’t] read.” — ABRAHAM LINCOLN

“Independent reading is critical,” Herron says. “Students who frequently read independently improve their comprehension,

ABOVE: DEB STEWART

stamina, writing, vocabulary, and grammar. These elements contribute to future success in college and beyond. Most importantly in my opinion, students who are given many opportunities to read independently, and who are empowered to select their own books, are more likely to be life-long learners. Cultivating a love of literature is one of my favorite parts of being a teacher.”

“I create time for students to read independently each day, and this time is purely for student enjoyment,” Stewart says about her Second Grade students.

Simpson also believes encouraging independent reading is essential in Middle School. She says that because of the increased workload and activities that is when student reading can begin to wane. “Technology demands so much of our students’ attention, we feel it’s even more important to remind them of how much they’ve always loved getting lost in great books.” For her, a large part of helping maintain this love is keeping up with the newest young adult titles. “We’re truly in a renaissance of young adult literature, filled with a multitude of genres and diverse topics. I enjoy keeping a robust classroom library in which (during a normal year) kids are allowed to selfcheck out whatever they please.

Middle School students at Sycamore also participate in an independent reading contest called Reading Rumble. Students fill out bookmarks about the books they’ve read and earn a point for every page. They may choose to add these points to their class’s total or subtract the same amount from a different class’s

total. Winning classes celebrate with a pizza party or treat. “It’s fun to see kids’ competitive spirits awaken,” Simpson says. “All in the name of books.”

Stewart believes reading independently and with free choice helps students develop a love of reading. She also says reading increases vocabulary and comprehension. When reading skills improve, students are better able to comprehend materials in all subject areas. “Research shows that students are more engaged when given an opportunity to choose a book based on their interests,” she says. “This leads to students being happier about and more committed to reading. I believe that the most critical skill for academic success is the ability to read well. When you create space for student choice, students take ownership and discover a passion for reading.“

ABOVE: MARISSA ARGUS

SHARING THE WORK, SPEAKING UP AND BUILDING CONFIDENCE

As one might guess, students have a wide range of comfort levels when it comes to public speaking. One of skills that Sycamore students learn, and build on as the progress through the grades, is how to present themselves and their work in front of an audience.

“Sharing our work with one another is very, very important,” Argus says of her Kindergarten students. “As part of writer’s workshop, there is always a student share at the end of our time together. I choose several students who have either modeled the skill we just discussed during our mini lesson or who tried

something innovative or completely new that I want to celebrate with the rest of the class. These shares not only help model great writing, but they bolster the confidence of the writers and help them see themselves as authors. Sometimes, I even use student writing to guide our next writing lesson.”

She cites an example that happened at the end of their first Writer’s Workshop unit when a child in her class, Will, wrote a book about a trip to a park, getting and subsequently losing a red balloon. “I used this book as the catalyst to the next writing unit, Personal Narratives, and his book served as an anchor text for the entire unit. We kept coming back to the idea of ‘Will’s Balloon Book’, and we noted all the features of personal narratives it had throughout our study. Using the kids’ own work in this way can sometimes be more powerful than a famous author.”

Chris Herron works with his Third Grade students on public speaking from the beginning of their year with him. “Students present their work to small groups of their peers. As the school year progresses, the public speaking gets easier through practice. We want to provide the students with many opportunities to hone this skill.”

“Throughout the year, a student’s confidence grows, and so does their risk inclination,” Simpson says of middle school students. “It’s hard to teach kids that failure is a large part of being creative. I think it helps to model risk-taking as a teacher. Letting kids know that sometimes my own ideas fall short of what I’ve intended, but that I value what I’ve learned from the experience, is a powerful teaching tool.”

SYCAMORE AND BEYOND

At Sycamore, the subjects do not exist as completely separate entities but overlap and interrelate as students make greater sense of the larger world. Language Arts builds skills that help Sycamore students to lay the foundation for future learning and develop abilities to think critically, evaluate, communicate effectively, reason, solve problems, and value diverse viewpoints in all classrooms and subject matter. Simpson says her Middle School students benefit from the teachers who have taught them as they progressed through the grades at Sycamore, and the communication among the different grade level teachers can help address potential challenges students may face. “We have spent many years vertically aligning our Language Arts curriculum, to make sure students’ learning is scaffolded and is without gaps or repetitions,” Simpson says. “We meet regularly with teachers in grades above and below what we teach.”

That communication with other teachers extends to families of

Sycamore students. “When kids know you care deeply about them and are interested in them, they are more willing to try and take risks,” Argus says. “I try to go out of my way to communicate with parents, siblings, and even grandparents as often as I can. When we know the children as people, we may pick up on subtle nuances that affect their learning. I try to make connections to what the children say to me in conversation as often as I can during my teaching. The classroom is all about relationships.”

“It’s important for teachers to provide feedback that is both honest and constructive, as well as to celebrate student success,” Stewart says. “Most importantly, I want students take pride in their own work.”

“One of the things that I love most about Sycamore is the promise that we make to parents to know and love their children. With this foundation in place, students are more likely to ‘buy in’ and strive to be contributing members of classroom discussions,” Herron says. “Our students can tell that their teachers love and care about them as individuals.” n

THANK YOU, TEACHERS + STAFF

FIRST ROW LEFT TO RIGHT: EMILIE MOLTER, JEFF EASTMAN, JANE LEEDS | SECOND ROW LEFT TO RIGHT: MELISSA BRANIGAN, COURTNEY CORCORAN, AMY DEROSA | THIRD ROW, LEFT TO RIGHT: RACHEL ILNICKI, JULIE CLAWSON, DAVID SCHUTH