5 minute read

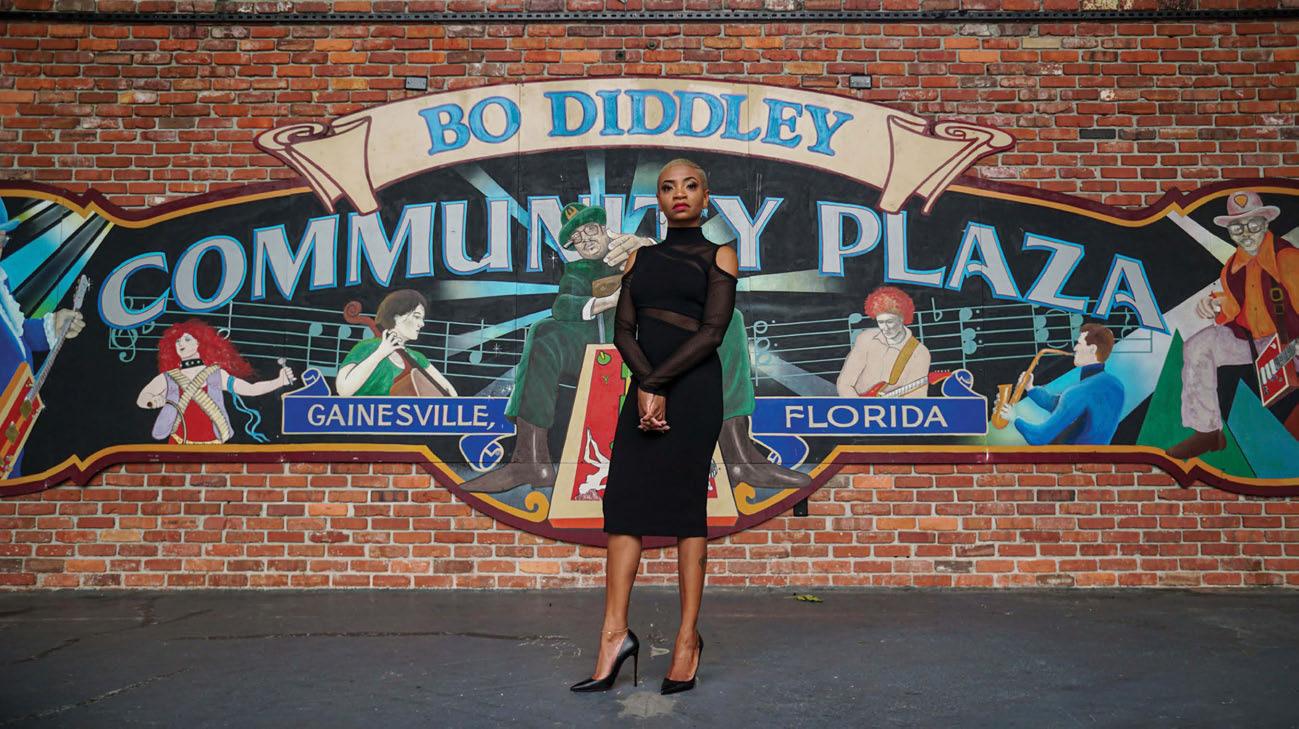

AERIEL LANE

Leading a March of 3,000 for the George Floyd Family

Story By: STAFF WRITER

Advertisement

The murder of George Floyd, a Minnessota Black man who took his final breaths in May 2020 pressed to the sidewalk under a police officer’s knee, was seen everywhere.

It played on a loop for viewers of national and international news. It appeared in everyone’s newsfeed on social media. It was the topic of podcasts, talk shows, and many other mediums of public conversation.

Coverage of Floyd’s death was also plastered across Aeriel Lane’s television. Aeriel is a Baltimore native who moved to Gainesville in 2013 with her then-husband and their biracial son.

“When the death of George Floyd occurred, I think like the rest of us, I was a little bit confused and trying to figure out what I could do to kind of affect some sort of change on at least a local level,” she said. “And I had a lot of questions. I’m African American, but does that mean that I have to do something? And if I do something, am I putting myself at risk? What can I do?”

Then, her 8-year-old son caught sight of the coverage.

“He looked at me and he asked me, ‘Could this happen to you, and could this happen to Mr. Sean,’ who is my partner.”

At first, Lane told him no.

“I realized that I wasn’t really telling him the truth because I didn’t know if it could happen to me or happen to a loved one or my family,” she said. “And I think at that point, when you’re a parent and you feel powerless, that’s when you’re like, ‘Okay, I have to do something.’”

TAKING ACTION TO BRING ABOUT CHANGE

At first, Lane attempted to join existing local efforts.

“I sent the mayor a message on Facebook and asked him if there was any type of activism planned around the city,” she said. “And he just responded, ‘Not that I know of.’”

Instead of accepting that there were no efforts to organize in Gainesville, Lane created a Facebook group to connect with local friends and plan a march in support of the Floyd family.

“I think I was operating purely on adrenaline and emotions,” she said. “I want to say I woke up and I was like, ‘Okay, it’s time to plan, plan, plan, and put it together and get it done.’ But really, I think the emotion of feeling helpless and powerless to yet another Black man dying, being publicly lynched,

was the only thing that was really driving me forward.”

Lane had to figure out a sidewalk route that would allow them to be socially distanced because of the COVID-19 pandemic and wouldn’t require a permit, since the permit office was closed. Then, she received a call from City Commissioner Gail Johnson.

“Basically, she was giving us permission to walk the road without a permit in the interest of public health and safety,” Lane said.

As the march grew closer, Lane’s nerves over leading it grew.

“The night before, all of these riots had started in Atlanta, and they were looting and shooting and it was just bad,” she said. “And I had a bad feeling that, you know, things were going to take an ugly turn, but I had to suck those fears down.”

The next morning, a call from her mother, Lorraine Lane, helped to calm her.

“When I spoke to my mom that morning, one of the first things she said was, ‘Your dad would be so proud of you,’” Lane said. “And I think while it gave me a lot of courage, it also gave me the feeling of having some really big shoes to fill.”

Aeriel’s father Ricky Lane, who died in 2004, was a former Black Panther. But Lane said that while he shared a lot of the values of an activist, when it came to raising his kids, he wanted them to decide for themselves how to think and act in the world.

“I am appreciative of the things that he shared with me growing up about being your own person,” she said. “When you see something that is wrong, if it is in you, stand up against whatever that wrong is in whatever way you see fit, and don’t let the crowd or the group sway you into decisionmaking.”

AN UNEXPECTED TURNOUT AND THE DAYS THAT FOLLOWED

For Lane, the morning of the march was filled with panic attacks and thoughts of turning around as she made her way to Depot Park.

“I was concerned about my safety and the safety of all the people who were planning to show up,” she said. “But by the time we got there and parked, I realized there was no turning back. So many people were there early, so many people were there with signs, so many people were there waiting to get started and ready to take on any task that we needed done.”

Lane’s friend Latalyia McKnight, who was also involved in planning the march, said that they only received 400 RSVPs for the march on Facebook. To their surprise, according to Lane, the actual turnout was between 2,500 - 3,000.

“When everyone took their places at (Bo Diddley Plaza) and I was able to look out over the crowd of 3,000 faces, I immediately broke down,” Lane said. “The emotions just came flooding over and out of me. It’s a moment I’ll never forget. And those same people have been supporting me ever since then.”

-Aeriel Lane

After the march, Lane, her partner Sean McIntosh, and her friends began to wonder what they could do to affect long-term change, which led to them forming the organization March for Our Freedom. The group focuses on efforts such as providing educational programs, helping to register voters, and supporting Black-owned businesses. They also work with local police to affect training policies.

Lane said that since the march, she’s also been focusing on educating her son about race and equality through reading, podcasts, and discussions ― ultimately teaching him that “‘Black Lives Matter’ isn’t just a saying.”