Southsea Coastal Scheme: Sub-Frontage 1 (UK)

Locally Manufactured

WINNER

SUSTAINABILITY AWARDS

Living Ports Project, Port of Vigo (Spain)

Validated Core Technology Meets Marine Construction Standards Enhancing Marine Biodiversity

WINNER

WINNER

Southsea Coastal Scheme: Sub-Frontage 1 (UK)

Locally Manufactured

WINNER

SUSTAINABILITY AWARDS

Living Ports Project, Port of Vigo (Spain)

Validated Core Technology Meets Marine Construction Standards Enhancing Marine Biodiversity

WINNER

WINNER

Mackley delivered urgent works to Ventnor frontage after a catastrophic failure of the seawall and promenade. This collaborative project reused timber from our Bournemouth groyne building programme, creating a more sustainable solution.

Mackley is a civil engineering contractor with 90 years’ experience of innovative engineering for our core business sectors.

Working in the water environment is not for the faint hearted. Nevertheless, with our skills in construction, ECI, design management, environmental mitigation and stakeholder management, Mackley has been tackling challenging projects, alongside our clients, ranging from construction management of programmes to emergency rapid response, across all our specialist sectors, for almost 100 years.

We deliver as a Tier 1 lead contractor or as a Tier 2 supply chain partner including design & build services. Our teams’ engineering capabilities help tailor designs and construction methods for buildability, and to build resilience and adaptation to climate change. Our objective is always to deliver low carbon solutions and construction methods to deliver biodiversity net gain and nature based solutions.

CIWEM

106-109 Saffron Hill, London

EC1N 8QS

Tel: +44(0)20 7831 3110

Fax: +44(0)20 7405 4967 admin@ciwem.org www.ciwem.org

Registered Charity No: 1043409

EDITOR

Jo Caird environment@ciwem.org

ADVERTISING

Lee Morris

+44 (0)203 900 0102 ciwem@syonmedia.com

SENIOR PARTNERSHIPS EXEC

Marieke Muller

+44(0)20 7269 5820 pr@ciwem.org

PUBLICATIONS MANAGER

Victoria Harris

+44(0)20 7831 3110 publications@ciwem.org

PRESIDENT Bushra Hussain president@ciwem.org

SYON MEDIA LTD

Unit 3, Boleyn Business Suite

Hever Castle Golf Club

Hever Road

Hever, Kent TN8 7NP

+44(0)20 3900 0145 www.syonmedia.com

ART EDITOR

Becca Macdonald becca@syonmedia.com

Copyright of editorial content is held by the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management (CIWEM).

Reproduction in whole or part is forbidden except with the express permission of the publisher. Data, discussion and conclusions developed by authors in this publication are not intended for use without independent substantiating investigation on the part of potential users. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of Syon Publishing, the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management (CIWEM) or any servants of those organisations. No responsibility for loss suffered by any person acting or refraining from acting as a result of the material contained in this publication will be accepted by Syon Publishing, CIWEM or its associated organisations.

The Environment magazine, printed by Stephens & George on Woodforce Silk, is accredited with FSC stock certification, which certifies the timber source originates from legal and sustainable forests. The Environment magazine uses vegetable inks formulated from renewable sources and has an Aqueous seal on the cover. ISO 14001: 2004 Environmental Management.

Management

AS SPEAKERS AND delegates ready themselves for the annual Flood & Coast conference and exhibition in Telford this month, this issue of The Environment explores the dual challenges of flooding and coastal erosion.

We speak to the Environment Agency’s Caroline Douglass ahead of the session she’s chairing at Flood & Coast about how the agency (our partner for the event, along with The Rivers Trust) is building resilience in the face of climate crisis, and helping the public to do so too.

Douglass calls for a “systems approach to a systems problem”, with the EA, other flood and coastal erosion risk management authorities (RMAs) and private owners rising to the challenge using a wide range of solutions.

Natural flood management will be a key piece of that puzzle – Mark Lloyd, CEO of The Rivers Trust takes us through how projects like wetland creation and tree planting can help slow the flow, as well as benefitting biodiversity and local communities.

That’s not to say that traditional flood and coastal erosion risk management assets have had their day – rather that they need to work in partnership with naturebased solutions. Maintaining grey infrastructure is an ongoing challenge for RMAs, particularly in the current financial climate, but partnership working and innovative technology have the potential to ease this burden.

With extreme weather events becoming more frequent, and our population continuing to grow, there’s no time to lose when it comes to planning for the future, whether that’s trialing new ways of adapting to coastal erosion, implementing legislation to address the risk of surface water flooding or looking back and learning from responses to past challenges. We explore all three approaches in this issue.

Whatever the route we take, it’s going to require us all to work together – agencies, charities, consultancies, academics and community groups – with CIWEM members and partners playing a key role as always.

Leading the way, as of last month, is our new CEO, Anna Daroy, who is looking forward to helping deliver essential changes needed across industry and within government. We offer her a warm welcome to the CIWEM family.

Jo Caird Editor, The Environment @jocaird

Writer and conservationist Isabella Tree on creating resilient landscapes through rewilding at the Knepp Estate in Sussex, and the new illustrated edition of her bestselling book

It was nearly 25 years ago that Isabella Tree and Charlie Burrell made the difficult decision to stop farming at Knepp, the 3,500-acre estate that Burrell had inherited from his grandparents. Unable to turn a profit, they sold their dairy herds and farm machinery and put their arable land out to contract. Free, finally, to be able to think “objectively and creatively about what was right” for their land, the couple began by restoring 350 acres of parkland at the centre of Knepp. Then, inspired by the work of the Dutch ecologist Dr Frans Vera,

they started the process of rewilding the rest of the estate – it continues to this day. Tree wrote about it – from introducing free-roaming herbivores, to restoring the river Adur – in her 2018 book Wilding – The Return of Nature to a British Farm. It has sold over 300,000 copies worldwide and has been translated into eight languages. Tree followed up in 2023 with The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding Big and Small, and in March she published a book for younger readers, Wilding: How to Bring Wildlife Back – An Illustrated Guide

WHAT’S THE THINKING BEHIND THE NEW ILLUSTRATED EDITION OF WILDING?

We had so many people asking, ‘Do you have anything for children to explain the whole thing?” Angela Hardy’s illustrations are so moody and evocative. Children will love it but their parents will have fun too.

HOW HAS REWILDING IMPACTED WATER QUALITY AT KNEPP?

Our water courses used to be very polluted. Water is still coming on to Knepp from farms around us that are conventionally farmed with chemical inputs; from roads; from industrial areas. But almost every stretch of standing water is fantastic water quality now –and there’s a lot of it, having created ponds, lakes and scrapes, let water to sit where it always wanted to sit, and rewetted the floodplain around the Adur.

“From

a nature restoration point of view, river catchments are such an obvious place

to focus because you’ve got that matrix of habitats”

We’ve got lots of indicator species that are coming back because of that improved water quality: invertebrates like the scarce chaser dragonfly, aquatic plants like water violet.

Our restored soils, now that they’re chemical free, are functioning as part of the ecosystem, and all that above-ground vegetation is acting as a filter. So we know that we can start cleaning our rivers if we start restoring our floodplains.

YOU SUCCESSFULLY RELEASED BEAVERS AT KNEPP IN 2022 – WHAT SORT OF CHANGES HAVE YOU SEEN SINCE THEN?

We haven’t got the full results yet of our beaver impact studies but we know from lots of other studies done in the UK that polluted water, once it’s passed through the settling tanks that the beavers create behind their dams, comes out clean. That’s a really big ecosystem service.

There’s also the big flood mitigation effect – the beavers alone are holding back about five acres of standing water in their six-acre pen. It’s incredible to see what happens with big rains – the

floodplain just rises, you can see it; the old moat around the 12th-century castle, that all fills up again.

TELL US ABOUT WEALD TO WAVES, WHICH CONNECTS A 160KM NATURE CORRIDOR FROM THE HIGH WEALD TO THE SUSSEX COAST

From a nature restoration point of view, river catchments are such an obvious place to focus. Because you’ve got that matrix of habitats – wetland and all the different degrees of wet and dry that you get around floodplains – which is fantastic for biodiversity. But also we need to clean our rivers, and having the three rivers – the Arun, the Adur and the Ouse – in the Weald to Waves project is focusing on exactly that. Not just increasing biodiversity, but also flood mitigation and water purification.

HOW CAN REWILDING HELP CREATE MORE CLIMATE RESILIENT LANDSCAPES?

What we’ve been noticing at Knepp is how resilient the land now is to drought. When we were farming, our heavy clay would just crack – you could literally put your hand into a crack up to your shoulder. It doesn’t do that anymore. You see it in the farmland around us, but you don’t see it at Knepp. In a healthy ecosystem, there is much more resilience

to temperature fluctuations than there is in a degraded, dysfunctional landscape.

HOW WOULD YOU CHARACTERISE ATTITUDES TO REWILDING AMONG FARMERS?

The media really enjoys polarising the argument and pitting farmers against rewilding, as if you can only have either nature restoration or farming – that’s not helpful at all. Rewilding is the life support system of farming. You can’t have one without the other. Rewilding provides the webbing that can run through even our intensively farmed areas to help support and increase yields – because you get more pollinating insects, you get natural pest control, soil structure is better.

If you leave the decision making to farmers themselves, they know their land better than anyone and quite often the ideas are much more radical than you could imagine. Farmers want to be able to do this kind of thing but they don’t want to be preached at.

It’s important that coming from government we have policy and legislation that holds polluters to account and, to a certain degree, financial incentives for switching to naturefriendly forms of farming. But government

is never going to have the will or the cash to do it in the dramatic way that it needs to be done. The cavalry is coming in the form of the private sector: companies being held to account for their environmental impact and needing to either offset their carbon and their biodiversity impacts, or just do the right thing and be seen to be investing in the future of the planet by releasing money for nature restoration. So there’s a lot of money now sloshing around for rewilding projects, which is incredibly exciting.

There’s always dreams of what could come next but really our sights now are on connectivity; how we can heal our landscape by holding hands with farmers, landowners and gardeners around us. We’ve got over 500 private gardens in the Weald to Waves project – communities too, school yards and playing fields – coming together to work with nature to create resilient and naturally beautiful gardens. Everybody can play a part in stitching together the tapestry of our landscape again. o

Wilding: How to Bring Wildlife BackAn Illustrated Guide, by Isabella Tree and illustrated by Angela Harding, is published by Macmillan

Gearing up for an exceptional event

Flood & Coast is the leading conference and exhibition dedicated to innovative solutions for Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management (FCERM).

In parallel to this years conference sub-theme of Innovation and Skills, our specific themes for each day will reflect the impact we aim to have for the Flood and Coast community through the content of that day. Working closely with the strategic partners for the respective days we will focus on:

• Day One: Flood and Coast Futures

• Day Two: Water and Us; Charting our Course to Success

• Day Three: Collaborating to Deliver Better Surface Water Management

Strategic Partners Register now

Thank you to our Sponsors and Exhibitors

Over 1,000 homes will be lost to erosion in North Norfolk over the next 100 years – Rob Goodliffe, coastal transition manager at Coastwise, stands defiantly at the cliff edge

Coastwise is part of the Coastal Transition Accelerator Programme (CTAP), funded by DEFRA and the Environment Agency. Rob

Goodliffe has spent the past 20 years working for North Norfolk District Council (NNDC) – engaged in activities such as delivering the UK’s first ‘sandscaping’ scheme, in preparation for climate-accelerated coastal erosion. CTAP is a government initiative designed to explore innovative methods for adapting to the impacts of climate change on coastlines. Launched in 2022, it focuses on working with communities in the East Riding of Yorkshire and North Norfolk. CTAP aligns with the National Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy for England, aiming to build a nation resilient to flooding and coastal change throughout the 21st century.

WHY IS CTAP SO IMPORTANT?

England’s coastlines are eroding at some of the fastest rates in Europe. While erosion is a natural process, rising sea levels due to climate change are accelerating this phenomenon in certain areas. Traditional methods of coastal protection may no longer be a viable solution in these locations.

With these heightened risks, CTAP aims to explore proactive solutions. The programme investigates how local authorities can collaborate with and support communities living, working and utilising coastlines that are no longer sustainably defendable.

WHY ARE COASTAL RISK MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES NOT ALWAYS SUITABLE?

Coastal risk management structures are often a preferred choice for many, however it’s not always that straightforward. In some locations it can be technically very challenging to prevent erosion, whether driven by coastal process or by geomorphological processes such as groundwater in cliffs.

If there are technical solutions, these also need to take into account environmental factors. For example: will they have negative impacts on nationally designated sites or will they exacerbate erosion elsewhere?

Finally, if risk management structures are technically possible while also being environmentally acceptable, can they be economically feasible? Funding for schemes can be sought from government, but they need to meet the funding criteria (which include aspects such as numbers of households at risk), and often additional funds are required from elsewhere. This can be a significant challenge.

With this in mind, if risk management structures aren’t possible, there should and could be other options available to assist with managing an eroding coast, so that people’s wellbeing, and a community’s vibrancy, can continue.

Through

working with communities,

those impacted

by coastal change

and

wider stakeholders

we will shine a

light on what is possible

HOW CAN THIS PROGRAMME INFLUENCE NATIONAL POLICY APPROACH?

At present there are very few options for anyone impacted by erosion, or for Risk Management Authorities (RMAs) who have limited opportunities, or powers, to take action. This is where Coastwise is seeking to help.

As well as seeking to prepare communities through transition planning and practical actions, a key objective is to learn what does and what does not work when seeking to adapt to our changing coast.

Through working with communities, those impacted by coastal change and wider stakeholders we will shine a light on what is possible and showcase opportunities where government could consider support. Through leadership,

policy, legislation and funding we will create a ‘transition space’ where RMAs are able to facilitate coastal transition. Working with infrastructure providers, communities and individuals will ensure that everyone is better informed and therefore better able to adapt.

TELL US ABOUT THE EAST RIDING PROJECT

Changing Coasts East Riding is a sister project to Coastwise, but there are new younger siblings too in Cornwall and Dorset, and cousins in the Flood and Coast Resilience Innovation Programme. We are all seeking to explore innovative approaches that can solve some of the tricky and emotive erosion and flood issues we face. East Riding and North Norfolk are completing separate programmes of work that fit with our respective organisations and seek to meet the local coastal change needs.

That said, there are areas which do overlap: in some case we are intentionally taking different approaches in order to learn different lessons; on others we are collaborating where we believe the greatest benefit for the programme and the nation can be gained. An example is that we are funding a role in the national Environment Agency team to support our work on innovating long-term sustainable funding and financing mechanisms for coastal transition. This is one of the underpinning needs if we are to ensure we can continue to transition in the future. o

The EA’s executive director of flood and coastal risk management talks to Jo Caird ahead of Flood & Coast 2024, where she will be chairing a session on creating a nation more resilient to flooding and coastal change

It’s just over a week since strong southerly winds and large waves caused parts of the south coast to experience their highest ever tides.

Many coastal roads were inundated, trains were unable to run in some places, and firefighters helped residents escape from dozens of flooded homes.

A fitting time to be interviewing Caroline Douglass, the Environment Agency’s (EA) executive director of flood and coastal risk management, you might think. But then, flood and storm events seem to be hitting the UK so frequently these days that it would be hard to find a time that wouldn’t be fitting.

“We are seeing the impacts of climate change now,” says Douglass, who visited sites in West Sussex last week to see the damage for herself. She reels off a list of other recent events that are likely to be a consequence of human-made global warming, including the wettest ever October-March period on record for England, and river level records broken on the Trent, the Thames, the Severn and the Avon.

“Climate change is continuing to happen,” Douglass goes on. “It comes

back to us to understand how we are managing those risks, helping people to understand them and making sure those climate change impacts are included in that risk assessment.”

She flags the Thames Estuary 2100 Plan, which sets out a vision for the estuary’s future in the context of rising sea levels, bigger, more frequent storms in the North Sea, and a growing local population.

“The public can’t always see the natural flood management solution upstream of them”

“We’ve got a fantastic Thames Barrier and flood walls now, but how are they going to adapt to climate change out to 2100? What do we need to do to be resilient in the future?”, asks Douglass. The plan includes considering locations for a new barrier to take over after the current one reaches the end of its design life in 2070, and assessing the resilience of existing defences throughout the estuary. Key, she adds, is updating the plan every

10 years, “based on the latest climate science, which is changing all the time”.

The Thames Barrier may be the second largest retractable flood barrier in the world, protecting one of the most populous cities in Europe, but it’s just one of thousands of flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) assets – both in the EA’s portfolio and owned by other risk management authorities and private owners – that will be under increasing pressure over the coming decades due to climate change.

Maintaining these assets, which protect millions of homes and businesses, as well as essential infrastructure and agricultural land, is already a matter of “hard choices”, given the funding available, says Douglass (see High maintenance, pp. 20-22).

Those choices are not going to get any easier as increasing numbers of assets near the end of their design lives. “The challenge for us is that there’s no one right solution,” Douglass acknowledges. “We’re working in a really complex system and if you’re working in a system, you need systems-based solutions.

“It might be walls, barriers, naturebased solutions (NBS), decommissioning and rebuilding, helping communities help themselves, planning. All of that is part of the puzzle that we’re trying to put together to be overall more resilient for the future. We know there’s an increasing risk from floods so what are we doing about it in all those different areas?”

Nature-based solutions will be a key piece of that puzzle, with the EA increasingly looking to include natural flood management (NFM) schemes alongside grey assets. “In the past we probably have looked at more fixed flood defences as the answer. Going forward, we’re going to need a combination,” says Douglass.

“Nature-based solutions are fantastic for the environment, fantastic for reducing flood risk. You’re slowing the flow using salt marshes or tidal areas, for example. It means you won’t have to increase the size of the fixed assets as much as you would have.”

In February the agency announced that 40 natural flood management projects around the country will benefit from a new £25 million funding pot that runs from now until March 2027 (see Nature’s way, pp. 16-19). It builds on the EA’s £15 million natural flood management pilot programme, which ran until 2021 – it created the equivalent of 1.6 million cubic metres of water storage and reduced flood risk to 15,000 homes.

“We are putting some good investment into nature-based solutions and developing some really strong evidence for their effectiveness,” says Douglass. Alongside rolling out more of these sorts of schemes, however, the EA has another job on its hands: communicating their value to those at risk of flooding.

“The public can’t always see the natural flood management solution that is upstream of them,” Douglass explains, pointing to Slowing the Flow at Pickering, an ongoing project to help tackle flooding in Pickering, North Yorkshire. Measures include constructing low-level bunds, planting trees, especially along streamsides and in the floodplain, restoring woody debris dams in small streams, and restoring wetlands.

“That work has had a huge impact,” Douglass goes on, “but local communities don’t see it because it’s not a wall in front of them. At the same time, people can be lulled into a false sense of security that the wall is going to protect them, when we know with climate change, traditional defences can and will be overwhelmed.”

Where new or replacement hard infrastructure is required in combination with NBS – Douglass stresses that “it’s always going to be a blend and that blend is going to change over time and vary according to location and we’ve got to stay open to that”– close attention must be paid to the carbon footprint of those assets.

Since 2019, the EA has had an organisational commitment to stop contributing to climate change through its own operational emissions. Having originally stated an aim to become a net zero organisation by 2030, in January the agency pushed that back to between 2045 and 2050, citing less reliance on offsetting and changes around where

offsetting will take place. As part of the drive to net zero, low carbon concrete is now a minimum requirement where it meets the EA’s specification, and business cases for any new flood schemes need to contain a carbon assessment.

“We need to make sure that we’re reducing our impact on climate,” says Douglass. “It’s the here and now as well as the longer-term view.”

The here and now is a key concern for another element of climate resilience: very short-range, geographically specific rainfall and flood forecasting, aka ‘nowcasting’. It’s an area that the EA is currently partnering with the Met Office on, developing and trialling models for this type of weather event.

“People can be lulled into a false sense of security that walls are going to protect them, when we know traditional defences can and will be overwhelmed”

“We know that thunderstorms can come about with as little as a couple of hours heads up, and it’s those storms that cause so much of the damage from a surface water perspective,” Douglass explains. “Nowcasting is about giving us a very short lead into what’s happening in the establishment of those thunderstorm events. That information then feeds into the Met Office’s weather warnings and our flood warning system.”

This work is helping the EA respond faster and more effectively to flood events, but it’s just as essential for members of the public, whom the agency wants to equip with the tools to manage their own flood risk. This is just one of the ways that the EA is trying to foster a wider culture of resilience, along with its annual Flood Awareness Week and targeted campaigns in previously flooded towns including Grimsby.

“It’s an ongoing challenge for people to be aware of their flood risk, to know what to do when it is flooding and to take action when they get a warning,” says Douglass. “There are local communities which have flood action groups who do an amazing job of helping communities

CAROLINE DOUGLASS JOINED the Environment Agency in 2013, taking up the role of executive director for flood and coastal risk management in 2021. Prior operational and strategic roles at the EA include director of incident management and resilience and area manager for Hertfordshire and North London.

In her native Australia Douglass worked with the state government in Victoria, holding senior roles in land, catchment and natural resource management, as well as leading and supporting bushfire and emergency response. She holds degrees and diplomas from the University of New England (Australia), the University of Wollongong, the Australia and New Zealand School of Government and the London Business School.

to understand what their risk is, but it’s something we need to work more on.

“We have over 5.5 billion properties at risk from flooding from rivers, sea and surface water and only 1.6 million properties have signed up to flood warnings.”

In this age of climate crisis, flooding events like those that hit the south coast last week are not going anywhere. Only by pulling together – with members of the public doing their bit alongside the important work of bodies like the EA – will we find our way through the coming storm. o

THIS FOOTBALL, COVERED in goose barnacles, was found washed up on a beach in Dorset after making its way across the Atlantic Ocean. Photographer Ryan Stalker then returned it to the sea to take this striking image, which judges selected as the overall winner of the British Wildlife Photographer of the Year Awards 2024. Goose barnacles are not native to the UK but wash up on the south and south-west coast after big Atlantic storms. This photo, while beautiful, flags the worrying issue of the risks associated with invasive species arriving on our shores and disrupting native wildlife – it’s not only our coastal infrastructure that’s at risk as climate change causes storm events to increase in strength and frequency.

As a global leader in sustainable design and engineering, Stantec helps clients reshape the world with flood alleviation and environmental resilience projects that redefine what’s possible for communities. With more than 30,000 people worldwide, our teams create transformational solutions that add value for people and the planet. At this year’s Flood and Coast event, we will be showcasing our work within integrated partnerships in the UK’s flood and coastal resilience sector, as well as shedding light on our global expertise.

In coastal Louisiana and the City of New Orleans, for instance, we work to deliver projects driven on a state, community, and federal level, supporting flood alleviation, community resilience, and ecosystem restoration on an incredible scale.

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the US Government needed to take immediate and significant steps to repair the damage, improve resiliency and reduce the risks from future hurricane weather events. The US Army Corps of Engineers embarked on the $14.6 billion (£11.7 billion) Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction system. The final piece of this system was the $731 million Permanent Canal Closures and Pumps (PCCP) design-build project, which saw Stantec take on the role of lead design engineer and architect.

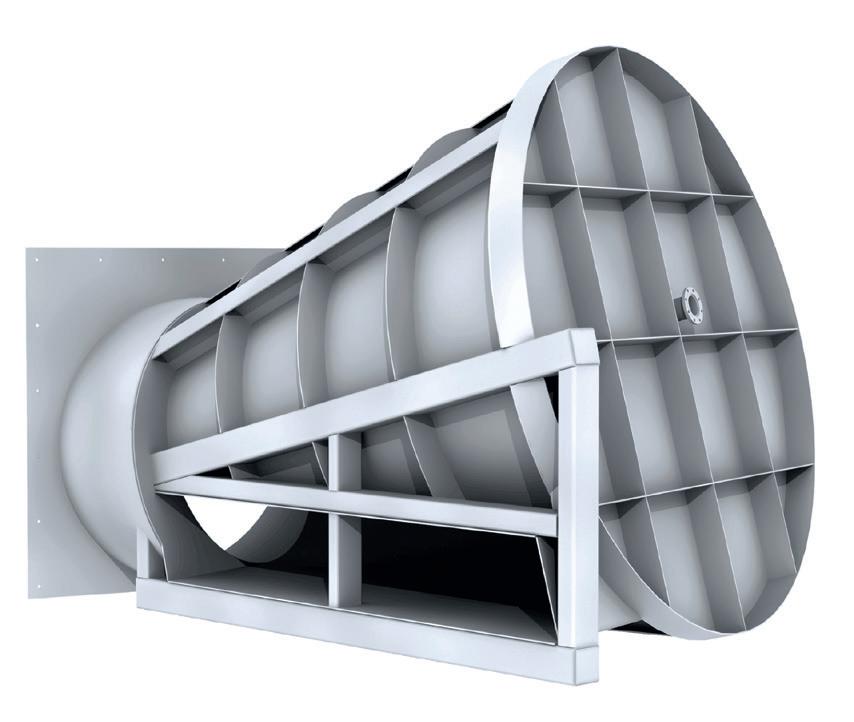

The PCCP project solution improves internal drainage resilience of the New Orleans flood control system, pumping water from three main drainage outfall canals with 18-foot high barrier gates into Lake Pontchartrain.

The massive pumps have a combined capacity of 24,300 cubic feet per second (688 cumecs) – enough to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in less than 4 seconds. While providing a long-term solution against a once in a hundred year storm event, this solution minimises acoustic and visual impacts for surrounding neighbourhoods.

Inside the city, however, water is still a huge part of New Orleans, as a city built on reclaimed marshland that has been continually drained of its water to make it habitable. Stantec’s landscape architects, engineers, hydrologists and urban planners are working with the City of New Orleans to think differently about how it can manage water as an asset.

The Blue and Green Corridors project is a network of eight miles of linear green infrastructure in the form of bioswales, linear wetlands, and floodable parks. The corridors receive flood waters, allowing them space in the neighbourhood to delay peak flood and mitigate impacts from the most frequent storms in the city. These long systems make the movement of water visible and act as beautiful

park-like connectors, linking recreational activities and inviting the community to move, play and socialise.

We are also working with the wider state of Louisiana and the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to deliver one of the largest nature-based solutions projects in the world.

Historically, sediment-rich water overflowed the banks of the Mississippi River and moved through coastal Louisiana, nourishing healthy coastal wetlands. However, the construction of levees along the lower Mississippi River has since prevented those regenerative flows. Resulting subsidence, combined with several other factors, results in the loss of a football pitch of land every 100 minutes. The purpose of the Mid-Breton Sediment Diversion project is to restore natural deltaic processes and again divert the sediment-laden Mississippi River waters back into the Breton Sound Basin.

A gated diversion system is being designed to divert approximately 50,000 cubic feet of water per second (1,414 cumecs), or 5 per cent of the Mississippi River during high flows, through existing levees to the Breton Sound. This project is considered key to reversing coastal land loss, improving flood risk resilience and helping ensure the health of Louisiana’s working coast.

BACK HERE IN the UK, collaboration, knowledge-sharing, and spearheading more integrated approaches in flood resilience help us shape programmes so they always have a meaningful impact. Here are a few water management partnerships we’re proud to be supporting across the country.

Hull and Haltemprice’s basin-like landscape impounds run-off, triggering regular flooding. To create true flood resilience and prepare and adapt to climate change, a collaborative, longterm vision was required, in the form of the Living with Water plan.

This plan required comprehensive consultation and collaboration between The Environment Agency, Hull City Council and East Riding of Yorkshire Council, community members, Yorkshire Water, academics, and experts across a variety of specialisms. As the lead engineers on the project, Stantec supported the strategic phase, employing a range of digital engagement and analysis tools and technology.

We have since developed flood resilience and innovative water management methods. Focusing on prioritising blue-green infrastructure, Nature-based Solutions and SuDS, we are helping create better places to live and work and reducing future flood risk.

The Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA), EA and United Utilities formed a forward-thinking

partnership to manage water differently. Taking a holistic and collaborative approach to water management, the partnership created an integrated water management plan (IWMP) and engaged Stantec to help.

With our partnership knowledge and experience and industry-recognised methodologies, we helped build a vision supporting objectives and created a series of seven workstreams to support the development of the IWMP. Through this collaboration, the partnership delivers progressive improvements in sustainable water management, enhancing the natural environment.

Enabling improved decision making, the plan will guide all future interventions to consider water neutrality, flood resilience and water quality, and build in climate adaptation. It aims to increase multifunctional blue-green infrastructure, restore natural function and water landscapes, as well as promote the protection and value of biodiversity and the water environment – for the benefit of everyone.

Further north, we are supporting the Northumbria Integrated Drainage Partnership (NIDP) – an award-winning collaborative stakeholder group set up between Northumbrian Water Group, the EA and 14 North East local councils. The partnership collectively addresses flooding and collaboratively minimises drainage issues by sharing resource and knowledge.

Each of the partnership’s schemes, of which Stantec is involved in

many, looks beyond a single source or responsibility, going above best practice to support a more resilient and sustainable region. These include bluegreen infrastructure through surface water separation, attenuation basins, wetlands, swales, bunds, daylighting watercourses, de-paving, rain gardens, source control, system optimisation and below ground storage. NIDP stands out in the industry by encompassing all of the North East, not just one city or area, having a record of successful delivery, and an ongoing plan that will deliver more in the years to come. The NIDP has already reduced flood risk to over 5,000 properties. o

JOIN US AT FLOOD & COAST WHERE WE’LL BE TALKING ABOUT OUR INVOLVEMENT IN THESE PARTNERSHIPS AND PROJECTS VIA A PANEL TALK. WE’LL ALSO BE ON STAND E39

Key services

o Flood mitigation and river basin management

o Nature-based solutions

o Reservoirs, dams and levees

o Pump stations and control structures

o Navigation structures

o Water resources and supply

o Wastewater recycling and water management

o Water quality, nutrient neutrality and bathing waters

o Coastal storm risk management

o Ecosystem restoration/living shores

o Blue carbon

o Offshore renewables

o Ports and harbours

o Coastal and marine servies

o Stormwater and urban drainage

Nature-based solutions, from leaky dams to treeplanting schemes, will be key to creating resilient ecosystems and communities, says Mark Lloyd, CEO of The Rivers Trust – if we can find a route to rolling them out on a wider scale

At a time when both public and private purses are tight, nature-based solutions (NBS) deliver multiple benefits and serve the interests of many different stakeholders.

They use natural features to address socio-environmental problems and are especially important in the context of water management. Interventions such as tree or hedge planting, leaky dams, wetlands, riparian buffers or floodplain reconnection help to restore or mimic the natural flow of water through the landscape. This alleviates the risk of flooding and droughts as well as filtering out pollutants and increasing biodiversity. With more than 65 local trusts across the UK and Ireland, the Rivers Trust

movement has decades of experience in getting boots on the ground – or wellies in the water – to protect, restore, and enhance our water environment. Our people are in their natural habitat when working outdoors, whether wading through the Wye or dipping in the Don. When we are working on solutions, we always aim to work with nature to restore

“Our precious rivers are currently blighted by pollution, altered from their natural state and often buried underground, with many species in decline and the wider landscape facing an increasing risk of both flooding and drought”

the most natural processes that will deliver long-term, integrated solutions for our rivers and catchments.

Nature-based solutions can also complement hard engineering to extend the lifespan of grey infrastructure, and make water treatment and flood defenses more efficient and cost-effective. In some cases they can even replace the need for chemical treatment and carbonhungry concrete solutions. They enable sustainable housing development, help businesses to reach their ESG goals and allow citizens to enjoy, and benefit from, a healthier environment.

A fantastic example of NBS at work is in South Norfolk, where the River Waveney Trust has worked with partners on a natural flood management (NFM) scheme. After the village of Gissing experienced terrible flooding in 2020, members of the public approached the trust about reconnecting a local stream to its historic floodplain. With support from Norfolk Rivers Trust, WWF, Aviva, the Environment Agency, and Essex & Suffolk Water, the team lowered the

stream banks in strategic places, as well as installing leaky dams and shallow scrapes to store water in Gissing and the surrounding area upstream of the village. Work was completed in September 2023, shortly before the arrival of Storm Babet and seven other named storms over the course of the winter.

“We weren’t expecting this work to be put to the test so quickly,” says Emily Winter, catchment officer at the River Waveney Trust, “but we’re really pleased to see it functioning as we’d hoped. This has been a fantastic example of a relatively simple and low-cost project that will have far-reaching, positive impacts for the local community.”

As well as protecting properties from flooding, these measures will store water and release it back into the environment slowly, mitigating the impacts of prolonged dry spells or drought in one of England’s most water-stressed areas.

“Nature-based

solutions can complement hard engineering to extend the lifespan of grey infrastructure and make water treatment and flood defenses

more efficient and cost-effective”

Further north, The Rivers Trust has also been involved with a pioneering NFM pilot project in Lancashire’s Wyre catchment. Between 2020 and 2022, partners from the Wyre NFM Investment Readiness project developed an innovative new financial model, blending public and private finance. This will see multiple beneficiary organisations such as local businesses repaid for their upfront investment in NBS through the sale of ecosystem services. More than 1,000 separate NBS interventions will take place throughout the catchment over nine years in order to reduce flood risk in the village of Churchtown, with the funds managed by a newly formed community interest company.

This project was a pilot for the Government’s Natural Environment Investment Readiness Fund (NEIRF). It was truly the first of its kind and is being used as a blueprint for how to attract private sector capital to finance natural

flood management. We are building on what we learned and innovating with new models of funding in locations across the country in a variety of catchments including the Cumbrian Glenderamackin above Keswick and the Yorkshire Aire upstream of Leeds. Although different in scale, the two projects in Norfolk and Lancashire

WHILE SOME NATURE-based solutions might only be suitable for a rural environment, plenty of these measures can – and should – be rolled out in cities and towns globally to address societal challenges including climate adaptation, food and water security, and biodiversity loss. With 55 per cent of the global population currently living in cities and urbanisation growing at an unprecendented rate, it’s vital that we factor in NBS when building and adapting the cities of tomorrow. Sustainable urban drainage systems, green corridors, roof gardens, river restoration, bioretention basins for storm water management, tree planting and more can all be part of the mix, depending on the specifics of the location.

demonstrate how the Rivers Trust movement is at the heart of delivering NBS, and I was delighted that each of them will now continue thanks to funding from Defra’s £25m NFM programme, announced in February.

The River Waveney Trust will build on its work to alleviate surface water and fluvial flood risk in Gissing by completing further NFM interventions within the Frenze Beck, Dickleburgh Stream and Stuston Beck catchments. Collaboration with the local community, landowners and parish council will be key as the measures include reconnection of an historic river channel, as well as further floodplain meadows, leaky dams and scrapes. While in Lancashire, the Wyre Rivers Trust will expand upon the learnings of the Wyre NFM pilot project by developing the Wyre Catchment Resilience programme. This will deliver a suite of targeted measures to further alleviate flood risk. Wetlands, ponds, riparian buffer strips and soil management measures will all be used, and are designed to ensure that all interventions maximise flood risk reduction while restoring natural processes. The local ecosystem will benefit from increased biodiversity and carbon storage, and local communities will enjoy increased climate resilience and amenities. These are just two of more than 20 projects led by local rivers trusts to

Businesses and organisations of all kinds must evolve to contribute to the global transition to a

A partnership with CIWEM is a powerful demonstration of this commitment.

marieke.muller@ciwem.org www.ciwem.org/business-partners

benefit from Defra’s NFM funding, but we need much more input, financially and politically, if we are to meet the challenges facing our environment. The £25m fund announced in September 2023 was hugely oversubscribed – funding could increase tenfold and there would still be plenty of initiatives to spend it on.

The urgency and scale with which we need to realise the potential of natural solutions is laid bare in our recently updated State of Our Rivers Report 2024 Our precious rivers are currently blighted by pollution, altered from their natural state and often buried underground, with many iconic species in decline and the wider landscape facing an increasing risk of both flooding and drought. Scant monitoring, weak regulation and enforcement, a lack of consideration for water in land management, and of course climate change are further exacerbating those pressures.

The Rivers Trust has long championed the integration of NBS on a large scale and we have the knowledge and skills to make it happen – but we can’t do it alone. And the trouble is that myriad hurdles stand in the way of organisations and landowners joining us.

“The Rivers Trust has long championed nature-based solutions on a large scale and we have the knowledge and skills to make it happen – but we can’t do it alone”

From the lack of standardised approaches and coordinated, consistent monitoring, to the need for more balanced permitting regimes for the water sector; from limited incentives for buyers and sellers of ecosystem services, to the absence of a cohesive market framework for these solutions, the many willing parties are currently struggling to deliver fully integrated solutions at the pace and scale we need.

That’s why we’re now ramping up our work through the Ofwat Innovation Fund’s mainstreaming nature-based solutions project, which we lead with United Utilities, Jacobs and Mott MacDonald. The aim of the project is

to remove the barriers to the adoption of NBS and develop new enabling mechanisms. There are five priority areas to unlock the opportunity to really embed NBS in land and water management:

● Working with regulators and policymakers to enable policy and regulation for NBS – engaging with the likes of the Environment Agency, Ofwat and DAERA in Northern Ireland to test fit-for-purpose regulatory requirements for NBS that will also drive greater value;

● Investment mechanisms for NBS – assessing and testing models and mechanisms that incentivise joinedup funding, planning and delivery, as well as creating a multi-million pound investment pipeline for the water industry to deliver better value for customers and beneficiaries;

● Standardisation and integration –standardised and consolidated tools and processes for designing, building, managing, monitoring, validating and verifying NBS, along with standardised

data and evidence for reporting on their impacts, to help to reduce the risk currently associated with NBS compared to the reliability of hard engineered solutions.

● Making NBS relevant and tangible –by using real-life or ongoing planned NBS, we’ll test our hypotheses, develop solutions, consolidate learnings, create joined up action plans and deliver greater value work, quicker.

● Coordination, steer and collaboration at national scale – pulling all workstreams into one coherent flow through continuous dissemination of learnings to further break down existing siloes in delivery of NBS.

These conversations and partnerships are finally starting to move the dial on nature-based solutions and make them a mainstream aspect of planning and infrastructure. We’re delighted to be joining CIWEM at the Flood & Coast Conference once again in June to keep up the momentum and ignite even more opportunity. o

As a triple whammy of aging, demographic change and climate change take their toll on our flood and coastal erosion risk management assets, many in the sector are concerned about our ability to respond to the maintenance burden, reports Jo Caird

It’s hardly surprising that there are around 6.1 million UK properties at risk of flooding. After all, most of our settlements are where they are because of their proximity to water.

The essentials of our relationship with water haven’t changed much over the 10,000 or so years since we abandoned our hunter-gatherer ways and embraced a settler lifestyle. But the demands that

we make on this precious resource, the complexity of the infrastructure that supports those demands, and our tolerance for discomfort and inconvenience in the face of flood events, certainly have.

The result is a network of hundreds of thousands of flood and coastal risk management (FCERM) assets spread across our nations and regions. There are around 256,000 of these assets in

England alone, 90,000 of which are owned and maintained directly by the Environment Agency (EA). The others are the responsibility of other parties including risk management authorities (RMAs) such as local authorities, lead local flood authorities, internal drainage boards, and water and sewerage companies, as well as private owners.

From sea walls to sluice gates, detention reservoirs to dams, these hard

assets are tasked with keeping water where we want it, whether that’s out of our homes, businesses and critical infrastructure, or off the agricultural land that’s yielding the food we eat. Thanks to anthropogenic climate change – which is seeing sea level rises and an increase in storm frequency and intensity – and population growth –which is leading to more development on our flood plains – these assets are

under greater pressure than ever before. It doesn’t help that many of them are coming to the end of their design lives. Their ability to do their job in these trying circumstances depends on us: large or small, coastal or fluvial, assets will only perform properly if they are maintained properly. There is concern in many parts that this is not happening. That despite the government investing a record £5.2 billion in new FCERM projects between 2021 and 2027, a lack of maintenance is seeing some assets deteriorate faster than would be expected, making them more likely to fail, endangering lives and property.

“From sea walls to sluice gates, detention reservoirs to dams, hard assets are tasked with keeping water where we want it, whether that’s out of our homes, businesses and critical infrastructure, or off agricultural land”

“That is more money than ever flowing in to build the new assets,” says Dr Andy Pearce, engineering team manager at Coastal Partners, which manages coastal flood and erosion risk across five local authorities on the south coast. “It’s the frustration of building them and watching them suffer from a lack of maintenance.”

The figures are important when it comes to understanding the scale of the challenge. According to Defra, of the approximately 36,000 FCERM assets owned by the EA that are classified as “high consequence”, around 94 per cent were at or above the required condition, as of October 2023 (prior to storms Babet and Ciarán). The figure for the approximately 27,000 high consequence assets owned by other parties was 90 per cent. Both figures fall well below the EA’s target of 98 per cent.

“We weren’t given enough money to meet that target,” says Caroline Douglass, the EA’s executive director for FCERM, citing inflationary pressures as well as increased costs associated with the Covid-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis.

“Our role is to try and do the best we can with the money that we have,” she

goes on. “Our high consequence assets are our priority: they’re protecting the most people and property. Then we scale back from there in terms of what we can do. There’s a risk in that –you can’t repair as many as you would like.”

Those choices are even starker for local authorities. While the EA receives funding from Defra to maintain its FCERM assets (£349.4 million a year in 2021/22), on top of that allocated for new capital projects, local authorities must pay for maintenance out of their general budgets. These budgets, of course, are under extreme pressure, with half of council leaders and chief executives in England surveyed by the Local Government Association in December 2023 saying they were not confident they will have enough funding to fulfil their legal duties in 2024/25.

And because all powers relating to flooding are permissive, explains Leslie Smith (not their real name), who works in flood strategy for a combined local authority, “when budgets are being squeezed, something that you don’t legally have to do is something quite easy to cut the money for”.

“Treatment wetlands are just one of many nature-based solutions that the sector could look to when it comes to bringing greater resilience to the FCERM ecosystem”

For many local and lead local flood authorities (LLFAs) a lack of funding and low public sector pay also contribute to a skills shortage in the field of FCERM asset maintenance. That only adds to the challenge of keeping assets in good condition.

While some are arguing for a reform of the funding for asset maintenance that would enable RMAs to draw, as the EA does, on a pot of central government funding, others are embracing ways to make current funding go further under the current system.

“If we work together we can pool our funding and deliver greater benefits for

less,” says Jonathan Glerum, head of sustainable growth at Anglian Water.

That might be through working with other RMAs, or it could mean partnering with charities like the Norfolk Rivers Trust, which operates and maintains several rural treatment wetlands on behalf of Anglian Water.

Treatment wetlands are just one of many nature-based solutions (NBS; see Nature’s Way, pp. 16-19) that the sector could look to when it comes to bringing greater resilience to the FCERM ecosystem. Natural flood management (NFM) will not be a silver bullet – NBS require long-term maintenance just as hard assets do, and will work alongside hard assets, rather than instead of them. But the interdisciplinary collaboration that NBS require offers “seeds of hope” for how FCERM assets might be maintained in future, argues Jonathan Simm, technical director for flood and water management at HR Wallingford.

The flood asset management system nationwide is complicated, with different bodies responsible for assets depending on their location, role, ownership, strategic importance and quirk of historic legislation. It’s simpler in some places – in Northern Ireland, for example, all FCERM assets fall under the remit of the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) or its arms-length bodies.

“We are fortunate because that does enable effective decision making on investment priorities,” says Andrew Hitchenor from DfI Rivers. He is quick to point out however that such a centralised approach would likely be more unruly in a larger or more populous area.

There is an awareness among the powers that be that the complexity of the current system could be improved upon. Defra is currently undertaking a review of statutory powers and responsibilities associated with FCREM assets with a view to providing a “robust evidence base and targeted findings to strengthen FCERM resilience through enhanced asset management”. It is due to be published later this year.

Whatever the findings of the review, more data sharing between RMAs will be

essential in terms of getting a handle on the work required to reduce flood risk. Decades of siloed working has led to the creation of multiple different systems of monitoring, classifying and maintaining FCERM assets. Such a system makes strategic investment very difficult and risks wasting resources on lower priority assets.

“New technologies – remote monitoring and machine learning – will make evidence gathering easier and cheaper”

Promising work is currently ongoing at both regional and national level, however, that will help to streamline these processes, from local authorities adopting evidence-based FCERM asset monitoring in line with that of the EA, to the development of a national register for coastal assets by the National Network of Regional Coastal Monitoring Programmes. New technologies – including remote sensing and monitoring, and the use of machine learning to spot patterns in data sets – will make this evidence gathering easier and cheaper. Some of this technology is already in use –heat-sensing drones to spot leaks, for example – but we’re not seeing huge scale change yet, argues Alex Jones (not their real name), who works in FCERM asset operations in the northwest.

“There’s a lot of talk about this within the industry, but we’re not in a position where we can say for definite that there are tools out there that can significantly streamline or be more cost effective,” they say.

But while technology, data sharing, partnership working, NBS and wide-scale systems reform all have the potential to bring meaningful change in this space, perhaps there’s something more fundamental that needs addressing here: our disconnect, as a society, from the water courses and bodies that enable our very existence.

As the climate crisis makes its presence felt ever more forcibly in our landscapes, flooding is going to get worse, and not better, no matter how much we throw at the problem. As a species, our reliance on water meant we had to find ways to live with flooding in the past; is it time for an honest discussion of how to start doing so again? o

Ridgeway have been distributing the innovative and bespoke Japanese Kyowa Filter Unit Rockbags® to the civil engineering and marine market in the UK, Europe, Africa and the Middle East since 2009.

Made from 100 per cent recycled rPET material, Ridgeway Rockbags® are a unique system that has proven to be more environmentally friendly and cost effective compared to traditional scour protection methods. Available in four sizes (2T, 4T, 8T and 12T) the system is available with dual and single membranes that can be adapted for different protection scenarios, therefore having the advanced durability and strength to deal with the challenging nature of the marine environment.

Ridgeway Rockbags® have many unique features – preparation of the product is a short process that requires reduced labour and machinery. Furthermore, in relation to installation, the one-point lifting ring allows fast and accurate placement, meaning that overall the system significantly reduces carbon emissions when compared to traditional waterway engineering methods. This is in addition to the co2 savings made using rPET. It is a highly flexible solution, making Kyowa Filter Unit Rockbags® very adaptable to complex marine projects.

Due to their porous nature Ridgeway Rockbags® are designed to withstand high velocities of flow, making them an ideal solution for protecting river embankments during flooding events and repairing damaged embankments post-flooding. They work by absorbing the energy and not deflecting or amplifying flows, which would result in scouring being pushed further downstream. Their porous nature also offers a great boost to the benthic and aquatic life within rivers. Flora and fauna, including small marine insects, build up on the surface of the Kyowa Filter Unit Rockbags® and in between the stone crevices, encouraging growth in the marine habitat.

To date the system has a significant track record in civil engineering projects, including the Mersey Gateway, Croston Village flood alleviation scheme in Lancashire, Thames Tideway, and the Grand Tortue Ahmeyim LNG project in Senegal to name just a few. Throughout these projects Ridgeway Rockbags® were successfully utilised at multiple locations, protecting vital infrastructure and maintaining their natural shape and aesthetics.

The Ridgeway Rockbags® team remain committed to upholding the highest standards for environmental responsibility and driving innovation

and sustainability in the civil engineering sector. With that in mind we have collaborated with two academic institutions to validate the cleanliness of our Ridgeway Rockbags®. Recent testing has provided evidence that Rockbags® do not omit any microplastics during their lifetime in the marine environment. Testing with academic institutions in line with the ISO standard 4484-2:2023 provides confidence to the marine civil engineering industry that the filter unit is 100 per cent safe for the marine environment. In fact, our experience worldwide for over 40 years is that the Filter Unit Rockbags® not only provide tremendous scour and erosion mitigation but also add additional benefits to the marine ecosystem such as the creation of artificial fish nurseries. o

For more information visit our website: rockbags.com

Or contact our business development manager, Paul Whitton

SDelivering lasting value to communities affected by storm overflow discharges will require significant investment and smarter solutions, argues Michael Rowlatt, a technical director at RPS, a Tetra Tech company which specialises in delivering wastewater services to the water industry and local authorities

torm overflow discharges from our sewerage systems to rivers, lakes and seas can impact water quality, reduce amenity value and prevent valuable human contact with our natural environment.

This is an issue which is high on the public agenda, with continued media coverage of the potential impact of storm overflow discharges. Water companies are now under pressure to deliver improvements.

The Storm Overflows Discharge Reduction Plan (SODRP), first published in August 2022, sets out headline targets

to protect the environment and public health, and ensure storm overflows operate only in unusually heavy rainfall events. Based on the rainfall target alone, according to the SODRP, “an estimated 80 per cent reduction in the number of spills is anticipated by 2050, relative to a 2020 baseline. This equates to a reduction of over 300,000 storm overflow discharges per year”.

With the mandated targets driving reductions in storm overflow discharges on an unprecedented scale, investment is also coming into the industry on an unprecedented scale. We are facing a

huge challenge, now and in the future, to deliver the system improvements required to meet targets and create enhanced natural capital for our communities.

So how do we ensure this investment is spent wisely? How do we ensure our communities receive robust and resilient solutions that deliver lasting value?

THE INVESTMENT REQUIRED

Whilst most people agree that the significant investment required to make change on such a scale is necessary, it will have to be paid for somehow, and this will in part be through increased

water bills for customers. As an industry, we therefore have a duty to do the right thing for our communities, by delivering maximum value from investment.

The development and reduced cost of remote sensing technology, analytical tools, and communication and data storage systems means we now have more data and greater understanding of the sewerage systems that serve our communities, allowing us to tackle this challenge in a smarter way.

“With targets driving reductions in storm overflow discharges on an unprecedented scale, investment is also coming into the industry on an unprecedented scale”

Every five years the water industry – along with the regulator Ofwat – goes through the price review process. This effectively sets out the investment available to water companies over the following five years. During the last price review, PR24, water companies estimated the types of interventions required to reduce storm overflow discharges in line with the targets in the SODRP, and the costs associated with these interventions went into their business plans for consideration by Ofwat. The final determinations from Ofwat are expected in December 2024, but work has already started to deliver interventions.

Whilst the interventions proposed in the business plans were as accurate as possible given the time and resources available to estimate them, there was not time to fully understand each issue in detail and devise solutions that would deliver greatest value overall. If we were to deliver the solutions as laid out in the business plans, therefore, we would not deliver best value to customers.

Whilst there is already pressure to start delivering solutions that have an immediate impact, the value of upfront planning must be recognised. Our sewerage networks are highly complex systems, with many factors that cannot easily be disaggregated from one another without intelligence and experience. If we can step back and take time to

PR24: BUILDING A BETTER FUTURE

Our methodology for PR24 sets out how we will drive companies to deliver more for customers and the environment. The methodology reflects our four key ambitions for the review:-

devise smarter solutions and optimise programmes of work, we will deliver much greater value and lasting benefits to communities.

Smarter solutions include:

● Identifying opportunities for shared benefit (ie, a solution at one location having benefit at other locations). This is done through understanding and modelling systems at catchmentscale; long-term planning; and considering multi-capital benefits, such as amenity value, biodiversity,

RPS/TETRA TECH was recently awarded a £100 million singleaward framework to support the improvement of river health across the north-west of England. Under this 10-year framework, engineers and scientists will drive programme optimisation; develop solutions; select preferred options based on best value, lowest carbon and cost; and provide design services to deliver reductions in storm overflow discharges.

carbon and public health, including mental health and wellbeing.

● Heavy emphasis on surface water runoff removal and sustainable drainage systems (SuDS), which help to reduce the need to create or supplement underground systems that have a high carbon cost and finite capacity, thereby delivering more sustainable solutions.

“Our sewerage networks are highly complex systems with many factors that cannot easily be disaggregated from one another without intelligence and experience”

● Public education campaigns – to explain why interventions are required or highlight the benefits of SuDS, for example – are an important part of these solutions, mitigating poor public perception and reputational damage to the industry.

● Solutions that are resilient and adaptable to the increases in rainfall intensity that are expected with climate change.

● Catchment-wide interventions, thinking outside the box (eg, catchment-wide reduction of surface water runoff through the adoption of SuDS at

community level, interceptor tunnels that avoid difficult site constraints and deliver a more efficient solution by allowing the problem to be dealt with in one place).

● Operational optimisation, through system understanding and collaboration with operators. This could be by making use of spare capacity available in our systems through proactive maintenance or smart network controls.

● Standardised solutions and components that reduce time taken to design and deliver solutions and help to de-risk programmes.

● Monitoring of interventions to ensure the required level of performance is achieved and maintained, providing the opportunity for proactive operation intervention if necessary.

At a programme level, we can deliver greater value by optimising the way in which solutions are delivered. Each solution will have its own drivers, such as the requirement to reduce spills or flooding, or the constraints that come with discharging to a bathing water, for example. But there are opportunities to coordinate delivery of solutions and employ adaptive planning to deliver benefits in an efficient way. We can do this by understanding drivers now and in the future – the visibility of long-term planning objectives

“A blurry line between client and consultant may be uncomfortable at first but has the potential to be a powerful relationship”

is therefore essential. This approach also allows ‘quick wins’ to be identified, as well as solutions that are independent of any other to be delivered as early as possible, meaning that communities feel the benefits sooner.

To deliver this kind of resilient

community infrastructure in an efficient manner we need intelligent, experienced and well-rounded staff in the industry, people who are empowered and motivated to do what’s best for the communities in which we work (regrettably, this has not always been the case). Buy-in from stakeholders is also required to give the agility and flexibility required for programme optimisation and make space for the necessary innovation to develop smarter solutions.

A move away from the traditional client/consultant relationship will also be beneficial. There is a huge amount of work to do and a collaborative ‘one-team’ approach means we can understand and make best use of the knowledge, skills and technology available to us. By doing so, we will be able to deliver most effectively for communities. Whilst this blurry line between client and consultant may be uncomfortable at first, it has the potential to be a powerful relationship if we get it right.

It would be easy to be daunted by the challenge at hand, but we have a real opportunity here to evolve and improve the way we work as an industry. Necessity is the mother of invention, after all.

One thing’s for sure: improving our environment and facilitating greater access to nature for our communities is essential, now and for generations to come. o

BThe soon-to-report London Climate Resilience Review highlights the many challenges facing the UK’s capital – and sets out what’s needed to tackle them. This isn’t the first time that London has overcome threats to its environment, writes Nick Higham, author of The Mercenary River

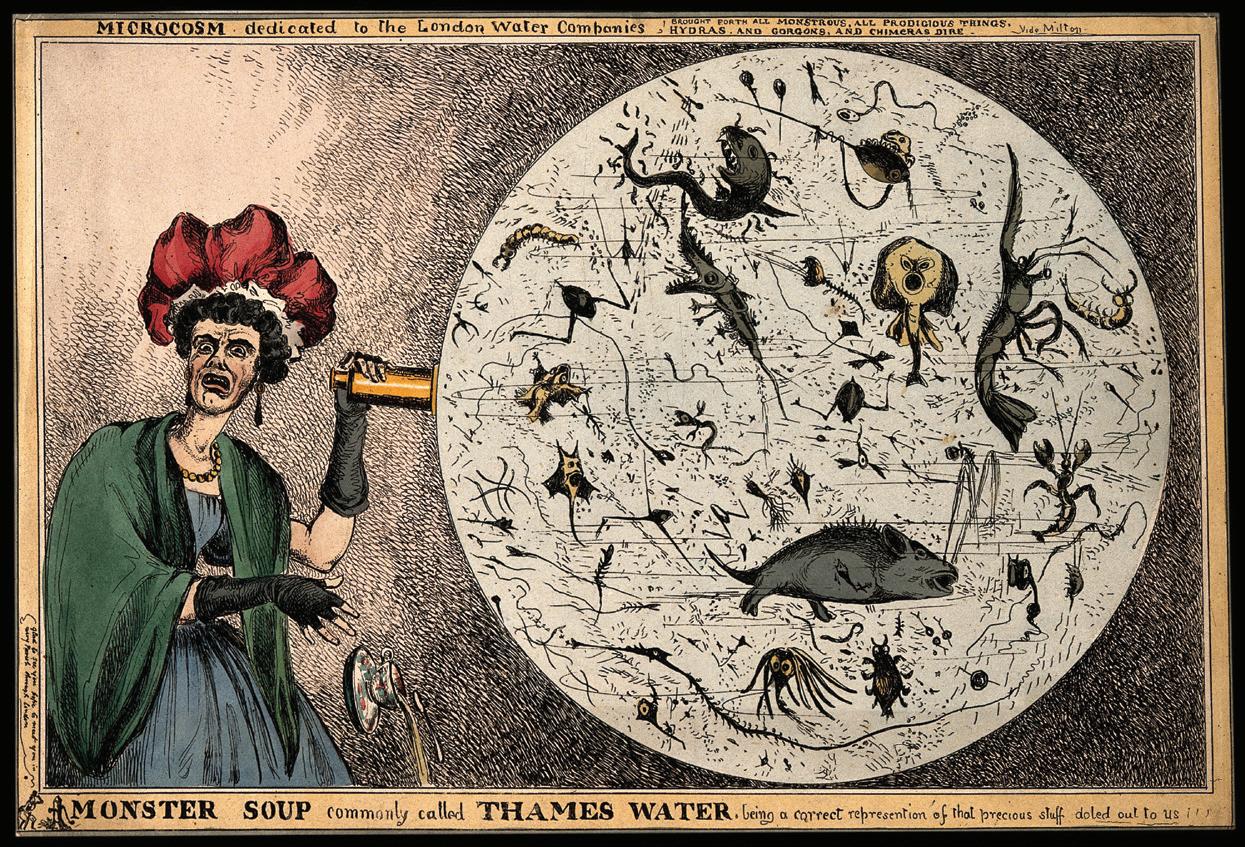

y modern standards the water which London’s early water companies supplied from the Thames and the River Lea was filthy, and for decades grew ever filthier. Not surprisingly, people noticed: London’s water became a frequent butt of satirists.

In A Description of a City Shower in 1710 Jonathan Swift had identified the contents of the sewers feeding the Thames: Sweepings from butchers’ stalls, dung, guts, and blood, Drowned puppies, stinking sprats, all drenched in mud, Dead cats, and turnip tops, come tumbling down the flood.

One of Swift’s contemporaries described Thames water itself as “foetido-cabbageous, dead-dogitious, dead-catitious, Fish-street-bilious”. And this was what most Londoners were forced to drink and wash with.

There were several reasons why the water was so dirty but by the early 19th century the most important was the growing popularity of the flushing water-closet.

For much of the city’s history, Londoners had been emptying their privies and chamber pots into bricklined cesspits under their property. They were periodically emptied by nightsoil men who loaded the fruits of their work onto carts or barges and took them out to the countryside to be sold to market gardeners as fertiliser.

The water-closet was not a new invention. Elizabeth I had one installed at Richmond Palace. There are references to them in the 17th and 18th centuries in the houses of the aristocracy. Then in 1778 a cabinet maker called Joseph Bramah took out a patent for an improved device, and by the 1820s water closets were in widespread use.

In 1847 almost half the houses in the parish of St Anne’s in Soho had a WC, and two-thirds in the more prosperous parish of St James’s in Westminster. Though you could turn that statistic round and marvel at the fact that a third, even in wealthy St James’s, still made do without a flushing loo.

“The most important reason why 19th-century Thames water was so dirty was the growing popularity of the flushing water-closet”

No doubt these WCs improved the quality of life for individual homeowners, but for the city as a whole they were a disaster.

The problem was that all that dirty water and faeces had to go somewhere, and traditional cesspits could not cope with the extra load. So people diverted the flow into the city’s sewers, which

had been designed merely to carry rainwater run-off, and emptied straight into the river.

Meanwhile the city was growing relentlessly: its population more than doubled to over two million between 1800 and 1850. The result was a tidal wave of effluent daily discharging into London’s rivers. It would, wrote The Builder in 1858, be “an act of insanity” to dip a mug into the Thames and drink the contents. Yet that, in effect, was what Londoners had been doing for years, courtesy of the city’s water companies. By the 1820s a new breed of consumer campaigners had emerged to tackle the problem. In 1827 an anonymous pamphlet targeted one company in particular among the eight serving the metropolis, the Grand Junction Waterworks.

At its launch in 1811 the Grand Junction had initially promised a supply of water from “the pure ethereal streams” of the rivers Colne and Brent to the west, brought to London via the Grand Junction canal. When the canal

company found there wasn’t enough water for both householders and boats, and customers complained that it was dirty, the intake had been switched to the Thames next to Chelsea Hospital. Unfortunately the intake pipe sat opposite the outlet of the Ranelagh sewer, which had started life as the River Westbourne but which by the 1820s had become heavily polluted.

The pamphlet conjured a nightmare vision of the company’s product, drawn as it was from near the sewer’s mouth, and led to the establishment of one of the first 19th-century royal commissions. There were three commissioners, including the distinguished engineer Thomas Telford, and some of the evidence they heard was stomach-churning.

One witness, whose home overlooked the tidal Thames, told of watching the carcasses of dead dogs float up and down with the tide. Dutch eel fishermen coming to London to sell their produce told of meeting the “bad water” as they came up the river – they knew it by the scum on the surface, and it killed up to two-thirds of their cargoes, which they kept alive in baskets slung over the side of their boats. Witnesses claimed to have found leeches, “shrimplike, skipping animalcules”, “oily scum”, a “stinking black deposit” and “little round black things, like juniper berries” in their water cisterns.

The campaigners called for government legislation to force the water companies to act. It was, said one, “the bounden duty of government, who ought to watch over the health of the people, to see that the town was plentifully supplied with good water”. Some went even further, demanding the water companies be taken into public ownership since water supply was obviously far too important to be left in the hands of private companies, who would prioritise their shareholders’ profits and dividends over their customers’ interests.

But that was going too far. Even legislation was looked at askance. Early 19th-century politicians of all stripes were wedded to the idea that private property was sacrosanct: governments had no business interfering with property owners’ freedom, and since shares in water companies were private property,

the government should stay well clear. And “interference” with the water companies would involve a dramatic widening of the role of government to include responsibility for public health. The Tory home secretary, Robert Peel, was aghast at the implications: government might end up responsible not just for water but for the gas and the lighting and the paving of streets.

“Hassall’s water samples were swarming with microscopic life: clusters of tiny cells, hairy globules, tangled filaments, all wonderful and fascinating, provided you didn’t have to drink them”

It took 30 years of campaigning and lobbying to bring about a shift in attitudes. Scientific investigation played a part. In 1850 a physician and botanist called Arthur Hassall published A Microscopic Examination of the Water Supplied to the Inhabitants of London and Surrounding Districts. The book

caused a sensation.

Hassall displayed his findings graphically in a circular frame, as if seen through the lens of the microscope. His samples of company water were swarming with microscopic life and the illustrations showed what they looked like: clusters of tiny cells, hairy globules, tangled filaments, all wonderful and fascinating, provided you didn’t have to drink them. Sewage pollution in the river showed up too, in the form of potato cells, wheat husks and fragments of muscular fibre. These, Hassall wrote, came from “faecal matter”. “It is thus beyond dispute,” he concluded, “that according to the present system of London’s water supply a portion of the inhabitants of the metropolis are made to consume, in some form or other, a portion of their own excrement, and moreover to pay for the privilege.”

After all this, even a reluctant government was forced to bow to pressure. In 1852 it passed a Metropolis Water Act. Almost all the water companies had been getting their water from the tidal stretches of the Thames

and Lea, where sewage surged backwards and forwards with every tide.

The new act required the companies to move their intakes to cleaner water much further upriver. It also told them to purify their product by passing it through filter beds and then to store it in covered reservoirs to prevent recontamination. The companies grumbled, but there was nothing they could do – and in any case London’s astonishingly rapid growth meant they were soon able to recoup the extra costs involved in making the changes by signing up new customers, and maintain a flow of dividends to their shareholders.

The river itself was finally cleansed following the Great Stink of 1858, when the hottest summer on record produced an unbearable stench and finally persuaded politicians (whose workplace sat right next to the fetid river) to fund Joseph Bazalgette’s system of intercepting sewers, then one of the largest civil engineering projects ever undertaken. For the most part it prevented raw sewage entering the river in the centre of the city, discharging it well downstream of the built-up area.

By that stage the pioneering epidemiologist John Snow had also demonstrated conclusively that at least one fatal disease, cholera, was carried in water contaminated with human faeces. His scientific peers initially rejected (and in some cases ridiculed) his findings, however, and it wasn’t until well after his death in 1858 that scientists and public health experts finally accepted that he had been right.

“The Metropolis Water Act 1852 required companies to move intakes to cleaner water further upriver”

A second Metropolis Water Act in 1871 trespassed even further on the freedom of the water company proprietors by establishing the first water regulators. These were a government inspector to oversee quality and a government auditor to make sure the companies didn’t cook the books.