8 minute read

MASKS, NOT ALWAYS A ONE-SIZE

By Tara Payor, Ph.D.

Dorothy Law Nolte expressed, “If children live with security, they learn to have faith in themselves and in those about them.” Making children feel secure is of the utmost importance before, during and after a pandemic. If parents undercut kids’ sense of security through negative talk in kids’ presence, there’s a risk in raising children who live in an unproductive cycle of conspiracy theories. At this unparalleled timepoint, parents are tasked with helping children understand that “those about them” are making decisions with everyone’s health in mind. With security as the scaffold, created by parents, community leaders, medical professionals and teachers, kids are better positioned for transition from surviving a pandemic to thriving well beyond its endpoint.

MASKED. NOT FORGOTTEN.

Reality: Masks are, for now, a fabric of life. Focusing energy on helping children realize their full potential, while masked, is wise. Doing that, smaller populations of kids—ones with exceptionalities that make them more susceptible to marginalization—can’t be forgotten. Ramona, whose 7-year-old son wears hearing aids, notes: “Asking him to advocate for himself all day is a tall order.” Hard-of-hearing children often rely on lip reading—impossible with masks. Ramona is concerned that hearing-impaired kids may not even know who is speaking: “I want the school to be a safe environment. I’m simultaneously concerned about how masking, with my son’s unique situation, may negatively affect both his learning and social development.” Intentionally supporting her son’s sense of security, Ramona encourages him to let adults know if he cannot hear. She’s hopeful the school district will demonstrate flexibility in masking policies. “The masks can get tangled in his hearing aids, and my worst fear is tangles leading to hearing aids falling out and getting damaged.” Cultivating security entails empathy. Consider things like, “what if my child missed large chunks of a lesson? Even as an adult, am I always able to advocate for myself?” The School District of Hillsborough County accounts for students who need accommodations and exempts masking when (a) instruction is impeded by mask wearing and (b) if hearing impaired people are involved. The American Academy of Pediatrics articulates that “special considerations and accommodations…account…for our vulnerable populations…with the goal of safe return to school.” Parents are called to help children feel secure as they embark on an academic year unlike any other. It’s achievable, in part, by assuring kids that all adults have the primary goal of kids’ well-being in learning environments.

MASKED. FOR GREATER GOOD.

Theresa, whose son was born hearing-impaired, underscores the need to instill a sense of security in both children and communities. “The shared goal begs

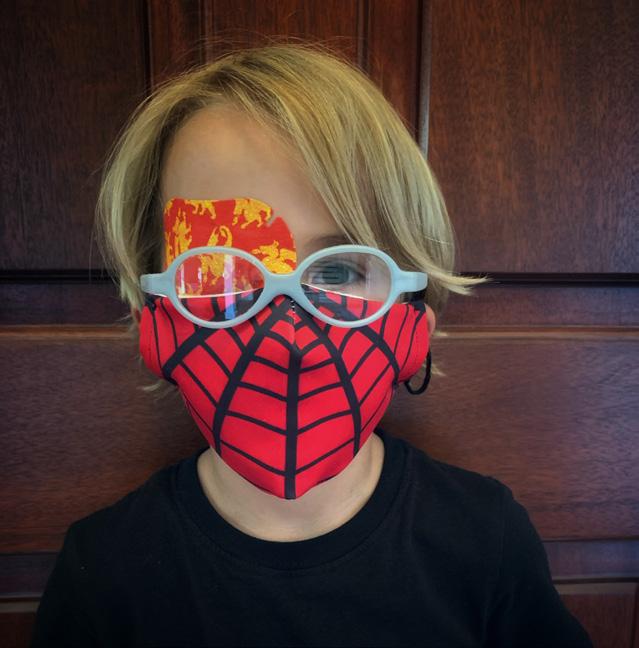

Payor was inspired by her own son's story:

Hendrix, 5, with all of his gear. He was born with a congenital cataract and had surgery at 2 weeks old to remove the lens of his left eye.

So, he wears a contact lens in the left eye and has to patch the right eye so that his left eye doesn’t become lazy. The plan was always to have surgery this summer so that a permanent lens could be put in. It would greatly improve quality of life for him. However, surgery has been put on hold due to the pandemic. understanding—safe, happy kids. Wearing a mask is an act of community service—just like stopping at a stop sign and getting to school on time.” It’s unlikely anyone is excited to mask, but adults can help kids feel good about it through positive, open conversations. When Theresa’s 6-year-old shares his feelings about masking and how it makes hearing even more challenging, she replies, “It’s hard. This is a challenge you will overcome.” Theresa taught self-advocacy early on, as people often interpret some hearing-impaired behaviors as lazy and distracted. As a mother, she’s also concerned with how masking may impact peer interactions. Ultimately, regardless of the accommodations available, she’s promoting mask wearing. “If face shields and masks with a clear mouth portion are options, it will help.” The health of all school community members is one of Theresa’s primary concerns, and she’s partnering with another mom to amplify the voices of kids with special needs within the context of COVID-19.

MASKED. ALWAYS ADAPTABLE.

While working on my Ph.D., I learned about adaptive expertise—being flexible in applying knowledge to novel situations. Sometimes, resistance is unproductive. I believe we have an opportunity for leaning into adaptability through pooling our knowledge bases, as parents, community leaders, medical professionals and teachers, with a shared, driving goal: a safe journey into one of life’s greatest adventures—an education.

MASKED & SECURE

Encourage masking by having kids make their own. Alternatively, use onhand supplies to embellish masks. Do consider mask integrity and limiting distractions in the classroom setting.

Since masking gets hands near the face, build excitement around washing reward stamps off hands before getting another stamp.

Talk to kids about the benefits of being back in the classroom when proper guidelines are followed (like desks three to six feet apart and not facing each other).

an EYE on Optical Health

By Anu Varma Panchal

During any normal year, parents’ schedules fill with appointments to the healthcare professionals who take care of our children: dentists, pediatricians and orthodontists. Those of us whose kiddos wear glasses or contacts also visit our eye doctors often.

But this is no normal year. And parents are hesitating to visit doctors because they fear the COVID-19 virus, even while they worry about issues with their children’s health. When it comes to eye health, if a child has been referred to an eye doctor by their pediatrician for any vision problems, it’s best to schedule that visit, with the understanding that medical practices have implemented all CDC protocols, including mask-wearing, sanitizing and social distancing.

“If you fail a vision screen early, you want to get that addressed, the earlier the better,” says Dr. Samantha Roland, a pediatric ophthalmologist in the Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital Department of Surgery. “The younger a child is, the more important it is.”

While Dr. Roland saw a dip in patient numbers during April and May, more patients have started coming back in now. One issue she has seen more of lately is children being brought in for excessive blinking. Dr Roland explains that when children focus intently on things close by, whether it’s a Zoom call or a book, their blink rate reduces drastically. While the blinking norm is an average of 8-21 times per minute, children who are super-focused on something close by can reduce this to as little as once a minute. This can cause their eyes to dry out, so when they get off the device or book, they blink excessively to compensate. While this blinking could just be a benign tic that the child could outgrow, it could also indicate problems, such as Dry Eye Syndrome or a need for glasses.

After a certain age, adults find is difficult to focus for extended periods of time on something close up, but children “accommodate,” or are able to do so for long stretches without seeming to strain. However, this accommodation can contribute to myopia, or near-sightedness. According to the International Myopia Institute, recent estimates show that 30 percent of the world is myopic, or near-sighted, a number that is expected to climb to 50 percent by 2050. In the United States, the prevalence of myopia is up to 42 percent, having almost doubled in three decades. Dr. Roland says myopia is also being detected at earlier ages. “It’s not necessarily COVID-related, but we’ll probably see a little bit of a faster rate because of it.”

The best way to catch and prevent eye problems is by seeing a doctor. Pediatricians spot many issues by using vision screeners to detect problems in infants as early as 18 months. Babies are born with poor vision, but rapid development occurs within the first year, and a child’s vision is completely developed by the time they are 9. If a pediatrician points out a vision problem with your child, it is important to see an eye specialist as quickly as possible to correct the problem. “If you’re screened at 18 or even 24 months, that’s early enough to correct vision and develop good vision,” says Dr. Roland.

TIPS FOR EYE HEALTH:

Decrease or minimize screen time to the extent possible. Encourage your child to participate in a mix of activities, including plenty of time spent outdoors. If they do want to watch or play something, use a television, which has a larger screen that is further away.

Make sure your child practices “near activity hygiene.” When reading a book, for example, this involves keeping a book 14-18 inches away from the face and making sure there is adequate lighting. Sitting at a desk and reading with good posture is better than reading in bed with the book pulled up close to the child’s face.

Teach children (and yourself!) the 20/ 20/20 rule: Every 20 minutes, look up from your screen or book and look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds.

Make sure children have a healthy diet rich in fruits and vegetables. “What’s good for your body is going to be good for the eyes,” Dr. Roland says.

Buy your little one sunglasses to protect them from harmful UV rays when they are outside. As for those popular blue filter glasses you may have seen people wearing lately to protect themselves from screens? Dr. Roland says there is no clear health benefit from wearing these as research does not show that blue light causes damage. Blue light is activating, however, which is why children should not use screens right before bedtime as it will prevent them from falling asleep right away.

Because there is potential for coronavirus infection through the eyes, the American Academy of Ophthalmology reminds children and adults to avoid rubbing their eyes. If you do feel like you need to rub your eyes or adjust your glasses, the Academy suggests using tissue rather than your fingers. Wash your hands frequently, especially before you touch your or your child’s eyes to administer drops or wipe them.